- Department of Arts and Culture, Erasmus University Rotterdam, Rotterdam, Netherlands

Markets and governments have been increasingly intertwined when it comes to funding for the arts. This is the case with matchfunding schemes in which governments explore the crowd’s validation by providing funds to successful cultural projects. By matching public funds with the “crowd”, four parties benefit from this process: the artists, the platform, the donors, and the public institutions. Artists benefit from accessing more funds and credibility signals for their projects; the platform benefits from enlarging the scope of funds given to artists; donors benefit from increasing the likelihood of project success; and public institutions benefit from granting part of the decision-making process on cultural budget to the crowd and cutting expenses on project management. This article conceptually explores the benefits, consequences, and the constraints of matchfunding mechanisms for policymaking. We argue that while matchfunding brings benefactors closer to policymaking and governments closer to novel funding models through online means, it also reduces the role of governments in elaborating cultural policy. It is vital to ponder the benefits and hindrances of this model given that matchfunding can potentially shift the structure of policymaking for the arts and culture.

Introduction

The entanglement of polity and economy is a long-debated topic in economic and political theories. Within cultural industries, this debate typically conveys how public and private agents guide their actions towards constructing a fruitful environment for the arts to flourish. Other than evaluating the mechanisms that better contribute to the arts, a political economy view on policymaking assesses the extent to which agents promote the arts through a top-down or more laissez-faire approach (Frey, 2000; Hetherington, 2017). Although these two realms may be seen as contradictory, cultural policy has also evolved in the direction of entanglement of private and public initiatives when it comes to funding culture (Dekker and Rodrigues, 2019).

Arts funding has been part of policy-related discussions for at least a quarter-century (Wyszomirski, 2004). Typically, cultural policy involves using organizational strategies to produce, disseminate, distribute, and consume the arts typically allocated within governmental budgeting (Hesmondhalgh and Pratt, 2005; Mulcahy, 2006). As such, common views of cultural policy attribute a special role to government decision-making in opposition to leaving decisions regarding the arts to be made by private actors (Frey, 2000). However, the state-led cultural policy tradition has been greatly marked by an increasing redistribution of authority, especially after major economic crises where a reduction of public funds brings more mixed funding strategies (Srakar and Čopič, 2012). One of the recent forms of combining policymaking with contemporary digital tools is the matchfunding strategy, in which a private or public institution donates additional funds to cultural projects, pre-approved by independent donors through small monetary contributions. This system is carried out via online crowdfunding platforms whose operations matchmake not only project creators with potential audiences, but also with institutional donors.

As this article shows, the digital matchfunding option ventured on online platforms is a powerful strategy whereby governments match third-party donors for specific causes such as charitable aid, arts-related programs, and support for early-stage businesses. Matchfunding supplements public subsidies by allowing additional private investment from other institutions (e.g., private funds, equity, other non-profit organizations or companies) combined with dispersed individuals, hereby called “the crowd.” The major difference between this novel form of matchfunding and any other mixed funding strategy widely used in public-private partnerships is that citizens pre-select their favorite campaigns via a “one-donation-one-vote” online mechanism, such as in typical crowdfunding campaigns (Belleflamme et al., 2014). By acknowledging the importance of different actors in budgetary decisions, governments open a rich avenue for collaboration of governments and citizens, within market-oriented platforms, thereby eroding the dichotomy of market-state initiatives.

A number of aspects are worth discussing in this case: 1) in digital matchfunding, both state and citizens make use of a private mechanism to support relevant fundraising campaigns. Unlike traditional (non-digital) mixed funding settings, the private party (an online platform) acts as an intermediary between the individual donor, the institutional donor, and the recipient; 2) as the crowdfunding “investor” consists of a plethora of individual dispersed donors, online matchfunding may dismiss critical views of “the market” interfering in policymaking1; 3) as in other typical crowdfunding settings, donors express their views about which types of artistic projects they wish to see further implemented and governments thereby adhere to the public’s preferences by respecting the crowd’s choice; 4) with a collection of dispersed donors2 deciding the directions of budget allocation for culture, governments can test the acceptance of their programs, thus alleviating the management of policymaking. As the paper further outlines, this may provoke cultural policy as we know it (see, e.g., Hesmondhalgh and Pratt, 2005; Mulcahy, 2006) to regress to earlier stages in which decision-making was restricted to simple budgetary allocation and was silent on the creation of coherent programs (Wyszomirski, 2004).

This new funding option poses several implications for all the actors involved and their respective incentives: the platform, the public institutions, and the donors. In order to discuss the benefits and constraints of this model to all parties involved, this article demonstrates the mechanisms of this funding model as well as its origins and main features. Secondly, this paper contributes to unveiling an emergent form of funding through which public actors and private individuals match incentives while replacing the figure of a single powerful patron. Third, the paper delineates avenues for further research related to the role of cultural policy and platform management when it comes to matchfunding options.

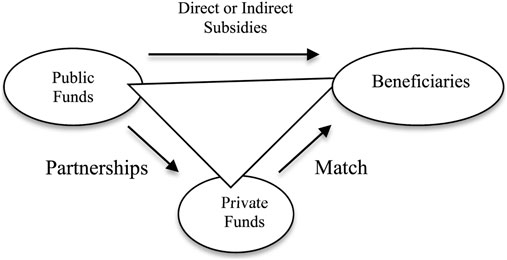

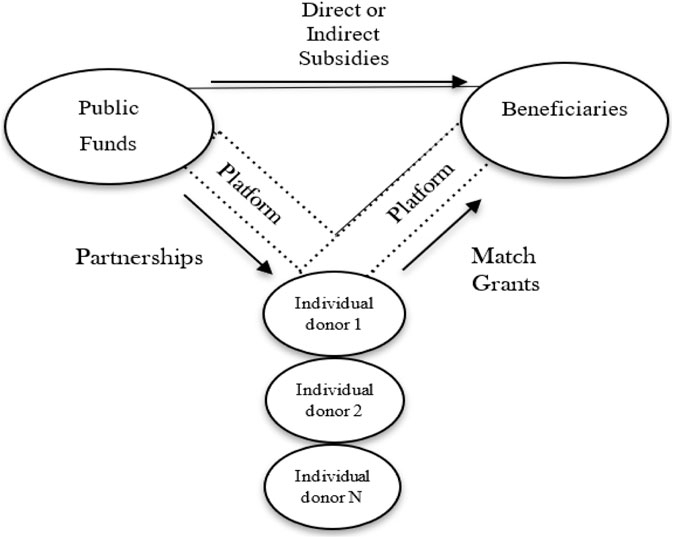

Mixed funding and the expansion of the private role

A long-lasting topic within the cultural policy is the shaping of programs that cater to diverse expressions, tastes, and preferences (Towse, 1994; Krebs and Pommerehne, 1995). Defining the optimal criteria to aggregate various preferences pays its tribute to early normative debates (Mazza, 2020) in which the allocation of funds is subject to value-judgement propositions (Surel, 2000). Under direct or indirect mechanisms, funding allocation is more recently delivered via a set of coherent actions which we call “cultural policy” (Wyszomirski, 2004). The direct public support for culture entails the implementation of subsidies, awards, grants, and any other direct form of transferring funds to beneficiaries. Indirect public support, on the other hand, is typically based on legal mechanisms aiming to provide funds for culture via indirect means, such as tax benefits. As Srakar and Čopič (2012) observe, from a fiscal point of view, direct and indirect support are equal in their withdrawal from the state budget.

Classical views regarding the role of cultural policies understand subsidies as tools for addressing the market failures in the arts (Fullerton, 1991; Peacock, 2000, Peacock, 2006). Subsidies are, thus, seen as consequences of either market failure or market inefficiencies (Austen-Smith, 1994). The state-centered view of funding for the arts typically deteriorates with subsequent economic crises, followed by a significant reduction of budget for cultural projects (Bonet and Donato, 2011; Čopič et al., 2011) and further re-evaluation of the worth of the arts (Bagwell et al., 2015). In these moments, governments may explore private support systems for cultural and creative industries (Srakar and Čopič, 2012), while cultural organizations explore alternative avenues for private support3. The private-based support system assumes various shapes: typically, donation, sponsorship in exchange for brand promotion, direct investment with capital returns, support from foundations, and contributions from individual citizens in exchange for tax exemption.

The excessive use of private support is often seen through critical lenses: culture thus becomes enacted as a commodified product under the guise of “neoliberal principles” (Miller and Yudice, 2002; Gray, 2007). In spite of these views, cultural policy approaches have increasingly welcomed different funding sources through public-private partnerships as they not only cover a funding gap, but also allow diverse ideas to flourish. Many of the recent developments towards understanding culture as a commercially driven activity essentially results from a dramatic change at the turn of the millenium when the term ‘creative industries’ became incorporated into the cultural policy lexicon worldwide (Granham, 2005; Marco-Serrano et al, 2014). Not surprisingly, the literature on arts entrepreneurship has also extensively grown since that period (Beckman and Essig, 2012; Chang and Wyszomirski, 2015). In other words, the elitist image of artists as purely intrinsically-motivated individuals with little regard for market mechanisms is replaced by an increasing incorporation within innovative and entrepreneurial domains.

In general, approaches to cultural policy - predominantly in Europe—changed to incorporate market-based forms of partnerships. The reinterpretation of what it means to carry out cultural policy is increasingly associated with creativity and innovation per definition (Hesmondalgh and Pratt, 2005). Policy papers such as the “Private Sector Policy for the Arts” (Art and Business, 2010) by DCMS and NESTA (UK) argue for building ambitious plans on matching grants and individual donations as a way to enhance innovation (Stanziola, 2012). The artist is further re-interpreted as an innovator, a creative entrepreneur, whose business-like skills need to be developed for further financial growth. This landscape is a spillover of the funding structure of policymaking in the sense that novel products deserve novel means of funding and distribution.

Matchfunding is not a new topic in cultural policy debates4. Originally, the mix of private-public funds was used for national and international emergency aid. For example, in the UK Aid Match case, the British government doubled each charitable contribution for poverty relief. Over the past 10 years, alternative funding models gained attention in cultural policy circles, especially if governments are willing to support projects already scrutinized by the public (Baeck et al., 2017). More recently, a similar strategy was used to mitigate the economic impact of the coronavirus pandemic for early-stage businesses (the “Future Fund” program in the UK). This option found great acceptance in contexts affected by the economic recession, as observed by Cacheda (2018)5.

In the arts, matched grants are currently incorporated within the crowdfunding model. In a report by (Baeck et al., 2017) commissioned by Nesta, DCMS6, and the Arts Council in England, matchfunding is announced as an innovative mechanism to fund cultural projects and provide long-term benefits to local communities. Online matchfunding is often suggested as a better method than indirect tax incentive strategies or direct lump sum benefits (Andreoni and Payne, 2010). The work of Andreoni and Payne (2010), and Gong and Grundy (2019), for example, show that matching grants is a superior strategy over tax incentives since they tend to reduce inefficiencies in public funding in the long run. Although scarce, empirical studies also show that the number of donations and the donor base increase with the matching grants option (Rushton, 2008).

Figures 1, 2 simplify the direct and indirect forms of fund allocation by governments and the matching grants option based on two scenarios: 1) one in which a single public institution is responsible for providing the matching grants, 2) and a second scenario in which the private party (an online platform) acts as an intermediary to match with various independent non-institutionalized supporters. While the first scenario implies that top-down cultural policymaking is in control of the acceptance of the project and the donation strategy, the second scenario outsources both the decision and mechanism to two private parties: the dispersed individual donors and the online intermediary that organizes the distribution of funds and information.

Types of matchfunding and the incentive mechanism

The literature on the matchfunding model via crowdfunding platforms is still in its infancy. Recent studies demonstrate that partnering with governments or other external funds tends to increase the success of crowdfunding calls (Montfort, Siebers and De Graaf, 2021). NESTA previously implemented a famous pilot study based on the platform Crowdfunder, whose results demonstrate how matchfunding calls are more likely to succeed compared to non-matchfunding calls within the crowdfunding system (Baeck et al., 2017). A study based on Goteo (a Spanish crowdfunding platform) also shows that: “campaigns with institutional support received on average 180% more from crowd donations than a campaign without institutional support. Other published compendiums also comprehensively summarized how public policies benefit from including online platforms in their funding initiatives and, ultimately, the crowd sponsoring model (Gajda et al., 2020). Also, the likelihood of success of crowdfunding projects backed by a combination of institutional partners and dispersed donors can be increased by up to 90%” (Baeck et al., 2017; 25). In this sense, the current literature, although limited in scope so far, provides overall positive outcomes when it comes to investing private or public funds to complete positively evaluated crowdfunding calls. In a recent study, Van Montfort et al. (2021) found that civic crowdfunding projects matched with extra funds by local governments does increase the chances of success.

A matchfunding initiative may adopt different strategies. According to Baeck et al. (2017), there are four matchfunding types currently in use by online crowdfunding platforms:

a) The “in first” model is initiated by a public or private institution that provides an advance investment to potential projects that still depend on the crowd’s approval. The independent supporters, thus, cover the remaining value through the platform. In this case, public institutions actively decide on favorite themes and further “screen” potential projects beforehand.7

b) In the “top-up” model, public or private institutions provide funds after the crowdfunding campaign has collected a pre-determined percentage of the target amount. In this case, the institution has less control over the campaign themes as the first criteria is the pre-acceptance by the audience. Ultimately, reaching (or not) the minimum threshold depends on the “crowd’s” decision.

c) Lastly, the “bridging” model incorporates the public or private institution contributions only after an initial amount is collected at the beginning of the campaign. Aiming to boost fundraising, this option is helpful to reward-based projects typically subject to the so-called “U-shape pattern” in which donations accumulate at the first and last campaign stages but struggle to receive contributions in between these stages.8

Institutions can choose whichever strategy better fits their programming and intentions in consultation with crowdfunding platforms. However, rather often matchfunding follows the second type aforementioned in which “the crowd” remains the first decision-maker, thus followed by the public or private institution that hypothetically abides by the crowd’s choices. For arts policymaking, such a mechanism implies several consequences should this type of matchfunding become the norm in cultural budget allocation. In the case of public institutions, governments become less concerned with sectorial programs and specific public policies for culture as the final decision-making relies on the “wisdom of the crowd” (Mollick and Nanda, 2016). Ultimately, the making of coherent programs and funds for culture provisioning represents a state-driven initiative (Mangset, 2020) which significantly loses importance within matchfunding structure. In such cases, public funds are less an instrument of a deliberate choice by a committee of experts within governments, and more a result of the public’s choice [see, e.g., Mollick and Nanda (2016)]. If the public’s choice is geographically-constrained, class-restricted, or income-dependent, cultural policy under matchfunding is equally restricted. Solutions to this problem involve, on the one hand, the expansion of crowdfunding platforms towards a better representation of a nation’s population, or the balancing of top-down and bottom-up cultural policy decision-making.

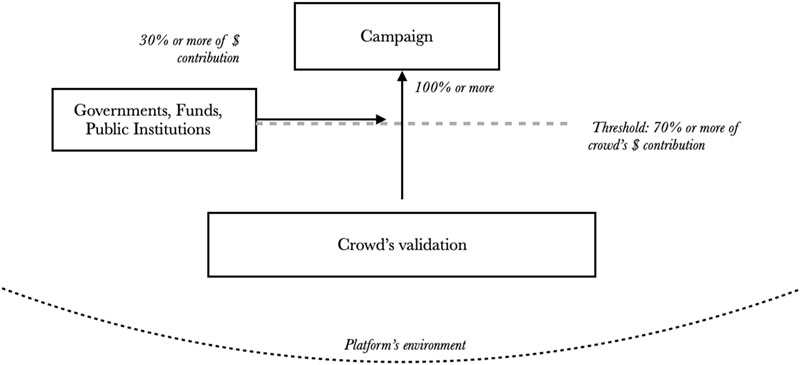

Figure 3 illustrates the basic matchfunding mechanism in which institutional intervention emerges as a consequence of the crowd’s quality screening. In the illustration, the public or private institutions and the platform together agree that funds will be provided as soon as a minimum of 70% of funds9 is collected from the crowd of dispersed individual supporters.

Matching the incentives for all involved parties

Typically, matchfunding intertwines bottom-up participation with top-down decision-making, hence offering several incentives to the involved parties. The next items will be dedicated to exploring some of the incentives, benefits, and hindrances for establishing novel public-private partnerships for cultural policymaking.

Incentives for public institutions: Outsourcing screening

From a state-led point of view, the opening of funding calls for projects, followed by selection processes, and justifying choices often requires considerable time and transaction costs involved in the management of cultural programs. The costs of law-abiding management principles and hierarchical decision-making prevails (McGuigan, 2004). With matchfunding, the costly quality screening process can be outsourced to external parties (e.g., crowdfunding platforms and, ultimately, the crowd). In this situation, governments act less as decision-makers and more as facilitators of public demands via the crowd’s validation.

We assume that all institutions (independent foundations, funds, lotteries, public-run organizations, and government bodies) may benefit from crowdfunding by means of 1) reducing communication costs, 2) allowing for a “hybrid democracy” rule in the use of cultural budget, 3) transferring the implementation of programs to a third party, and 4) outsourcing quality screening procedures. These benefits stem from the incentives that institutions have from outsourcing costly procedures and, consequently, relying on a “consumer sovereignty” doctrine thereby transforming the object of policymaking into a subject (i.e., instead of passively being the recipient of public goods, citizens dispersedly become the active part in the decision-making process).

The hindrance of these incentives lies in the matchmaking mechanism itself and the implementation of the project, both distant from the government sphere of control. Once the decision-making about which project to select and implementation of it leave any centralized control, accountability and enforcement rules also become more dispersed. While prior to matchfunding only one party was accountable for the provisioning of cultural programs, now an assortment of private agents partakes in this process with similar voting power. The consequence is a welfare decreasing result for donors in case the crowdfunding campaign eventually fails to deliver its products and, subsequently, for public bodies whose goal is a fair provisioning of access to culture.

Incentives for platforms and project creators: External credible signals

The second actor is the new online intermediary: the platform that adopts a pilot matchfunding strategy. The central incentive involved in a matchfunding scheme is surely accessing extra monetary funds which is translated into higher income to platforms operating in a competitive environment. Next to the financial incentives, platforms increase their legitimacy by welcoming the credibility signal of established institutions with good public reputation (Senabre and Morell, 2018). Similar to the credibility signals expected of crowdfunding campaigns, platforms too are subject to the same quality judgement. In a context of high information asymmetry, typical of crowdfunding (Handke and Dalla Chiesa, 2022) and cultural sectors in general (Caves, 2000), platforms may adopt strategies to eliminate mistrust and, hence expand the pool of potential supporters and project creators. As previous studies show, the mistrust of potential donors on the campaign’s products, or the platform’s payment system can discourage crowdfunding participation in countries where crowdfunding is not yet widely adopted (Rodriguez-Ricardo et al., 2018). The transparency of crowdfunding procedures, detailed descriptions of projects, proximity, and constant updates are vital to build credibility towards the audience and increase success-rate of projects (Mollick, 2014; De Voldere and Zeko, 2017; Wehnert et al., 2019; Katseli and Boufounou, 2020; Moysidou and Hausberg, 2020).

From the platform’s viewpoint, two main benefits apply: 1) higher success rates (Van Montfort et al., 2021), and 2) crowding-in effects resulting from external validation attributed to the platform by means of credibility signals (and, in extension, to creators). Contrary to a “crowding out” principle in which public funds would offer adverse incentives for private investment (Frey, 2000), matchfunding offers a more sophisticated mechanism to invite private investment without crowding out participation. The risk associated with supporting unknown artists is also shared by various parties, which significantly decreases the negative consequences of managerial misconduct over the course of a project.

Both the platform and project founders benefit from positive credibility signals attached to its operations along with the guarantee of fairness from partnering with well-known institutions. Project creators (artists, managers, cultural workers, etc.) access similar incentives as credibility signals conveyed by the platform tend to spillover to projects themselves (Rykkja et al., 2020) Secondly, the possibility of bypassing the hierarchical decision-making process of subsidy demand, grants, and bank loans is vital to a dynamic entrepreneurial economy (Feder and Katz-Gerro, 2015).

The hindrances for platforms are more limited than those expected for governmental decision-making. We can expect shortcomings when it comes to guaranteeing the cultural product’s delivery, or its quality. Typically, platforms are not liable for the quality or non-delivery of crowdfunded projects. However, fraud rates in crowdfunding have been historically low, while delay is a constant (Mollick, 2014). This may denote that the risks associated with reward-based crowdfunding are much more limited than those expected in equity based or profit-sharing options, thereby exempting platforms from extra quality control. Whilst this does not mean lower quality of projects, it can represent the limited skillset of project creators who often overestimate their capabilities or underestimate the costs involved with setting up a successful crowdfunding campaign (Agrawal et al., 2014; Mollick 2014).

For creators, shortcomings of this model are also limited since any additional funds are much welcome in a scenario of great online competition among cultural projects. Hindrances can be observed from a welfare perspective, rather than an individual one as, per definition, the more crowdfunding rules the mechanisms of arts provisioning, the less long-term policymaking becomes the norm. Ideally, artists and cultural creators should benefit from both long-run cultural policy strategies—in which the individual creator’s role is a passive one—and short-run crowdfunding campaigns led by the crowd’s validation. This way, cultural creators can benefit from both established top-down policies and, at the same time, act as active mobilizers of the projects they wish to see provided to their audiences whilst in direct contact with them via online platforms.

Incentives for donors and the non-use value

Extensive success-factor research shows that donors extract non-use value of crowdfunding for cultural projects (Boeuf et al., 2014; Cecere et al., 2017; Kuppuswammy and Bayus, 2017). Within matchfunding, this finding is not different as projects' features remain the same. Most arts-related campaigns offer memorabilia and symbolic reward items expressing gratitude towards donors. These most often can be considered items of non-commercial use, non-market benefits and non-monetary. The higher success rates in these types of projects may demonstrate both that funders are more attracted to campaigns that display a public benefit, public good attributes, or community contributions (Davies, 2015), and that the risks associated with such projects are perceived as lower, which is reflected in low target goals, and hence higher success probability (Handke and Dalla Chiesa, 2022). One can argue that the “private party” involved in crowdfunding acts in a more public than private way.10 This means that backers increase their utility by helping a project thrive, exerting warm-glow benefits or altruism towards the arts. This way, matchfunding manages to partially solve the underfunding problem of artistic projects by welcoming several private partners whose intrinsic motivation exerts more public benefits and less use-value. Further research can address such issues empirically by making use of testable assumptions.

Although funders may face lower transaction costs of investment in crowdfunding platforms compared to traditional investment methods, they may not contribute to projects if there are lower chances of success (Chang, 2020; Handke and Dalla Chiesa, 2022). However, by guaranteeing extra funds from institutional supporters, donors perceive the signal that their investment is not in vain as the chances of success are higher. An example by a pilot project in the UK shows how donors would not have supported online campaigns if public institutions were not part of the matchfunding scheme (Baeck et al., 2017). One can, thus, expect that institutional funding within crowdfunding schemes for the arts tend to act as a complement rather than substitute to individual private donation. Furthermore, as the crowdfunding system becomes overall more credible and reliable through matchfunding, more users feel compelled to support such initiatives. In essence, the strengthening of this system benefits all parties, but more importantly, if donors mistrust the process all perceived institutional benefits are in vain.

A few matchfunding cases

Arguably, digital matchfunding cases have been at the forefront of the dissemination and reporting strategies undertaken by the British arts-related bodies such as the Arts Council, DCMS, and reinforced by the European Commission (Odorovic et al., 2021). Other than the government directives, platforms may include the matchfunding option as a differential service to creators. To some extent, this sets them apart from other general-purpose crowdfunding platforms that do not offer a wide range of matchmaking options. Most crowdfunding platforms with a reward-based focus accept projects in the arts and wider creative industries (design, fashion, technology, and video games, for example).

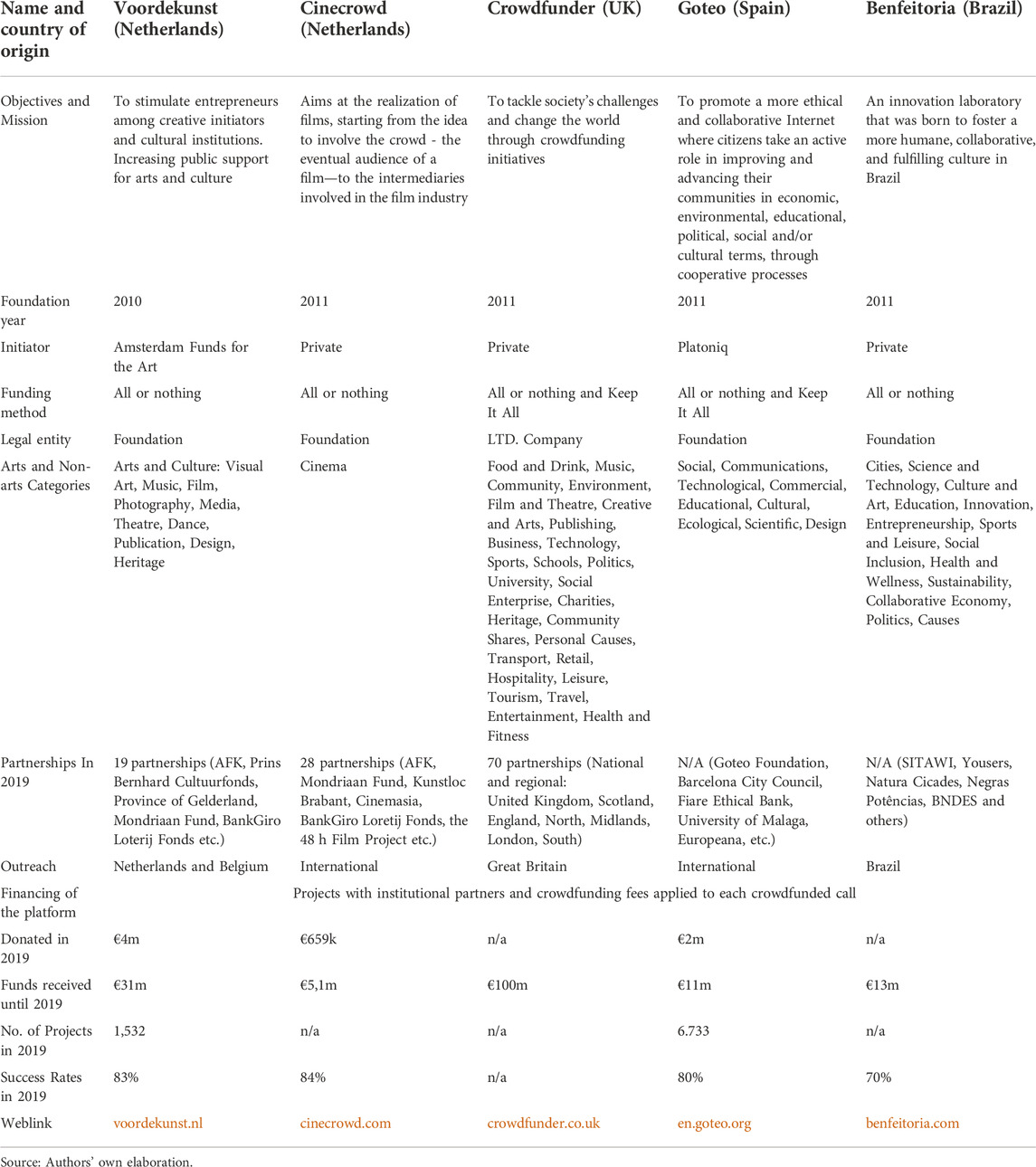

Since 2010, in the Netherlands, Voordekunst allows the combination of funds from backers and other contributions partially or totally supported by governmental funds, such as the Amsterdam Funds for the Arts. Nowadays, Voordekunst creates partnerships with local funds (corresponding to each region in the Netherlands), which typically focus on specific themes: Prins Bernhard Culture fonds, Province of Gelderland, Mondiaan Fund, BankGiro Loterij Fonds, etc. The platform Crowdfunder in the UK is, to this date, the most well-known example that has welcomed several governmental projects related to charity and business development. Also, in the Netherlands, some platforms emerge with a sectorial focus on matchfunding, which is the case of Cinecrowd which promotes crowdfunding projects for small local filmmaking productions. In Spain, Goteo largely welcomes projects with clear social, political, or cultural themes. Outside European borders, the case of Benfeitoria in Brazil emerged in the same period as the other platforms (2010–2011) with a focus on social innovation projects and major partnerships with private companies aiming to implement corporate social responsibility policies (CSR). In this case, matchfunding is dislocated from the governmental sphere, making this a unique case and relatively distant from this paper’s analysis.

Interestingly, the abovementioned platforms are structured as non-profit-oriented foundations, differently from platforms such as Kickstarter which operate as a private company. Their funding structure, nevertheless, remains similar to all other reward-based platforms: the online platform charges a fixed fee over the total funds raised by the project creator. Because of their successful partnership and endorsement signals by third parties, platforms whose strategy includes matchfunding tend to reach higher success rates. This may result from strong local ties, higher success rates in specific project types (i.e., projects with low target goals, tend to reach success most frequently) or having closer advisory provided by the platform officers to the founders.11

Regulations in crowdfunding vary greatly not only regarding different geographical areas (countries and regional blocs, such as the European Union’s regulations) but also when it comes to crowdfunding models12 (Lazzaro and Noonan, 2020). As for matchfunding schemes (one type of crowdfunding), platforms typically establish their mechanisms together with cultural officers in governments or semi-public institutions. Table 1 explores current examples from different regions utilizing matchfunding options, their revenues as per their active websites, and annual reports made available online by the online crowdfunding platforms over the year 2019. Most examples are European based, except Benfeitoria, a Brazilian website, which we add for comparisons amongst different matchfunding models available worldwide.

The limits of matchfunding: A policymaking strategy?

It is worth noticing that the use of crowdfunding for artistic and cultural projects is still very limited in terms of its demographics and geographic outreach. Most users are rather young13 (both project creators and funders), highly educated and living in urban environments (Mollick, 2014; Breznitz and Noonan, 2020). This often represents a fraction of a nation’s population, especially in less privileged areas. Furthermore, donors cannot always can access tax benefits from their donations14, which implies that the overlapping of a state-led cultural budget with crowdfunding puts contributors on the spotlight as the main people responsible for arts-provisioning. First, as taxpayers; secondly, as supporters of crowdfunding initiatives. Such an effect is not as evident because the pool of supporters is not representative of the entire population in most countries where this option is available. As such, the power of a decentralized low-cost funding system does not entirely overrun the benefits of long-term policies dedicated to making the arts accessible to different social classes, ages, and regions within specific countries.

Secondly, one of the greatest benefits of crowdfunding is its low-entry barrier. Informal projects, semi-organized cultural creators, early-stage entrepreneurs, and product prototypes share the access to a highly decentralized, bottom-up system, similar to open source and crowdsourcing initiatives facilitated by online infrastructures (see Frischmann, 2014). Similar to the cultural commons governance (Ostrom and Hess, 2007) and local participatory systems (Michels and Graaf, 2010), crowdfunding’s openness allows creators with limited access to financial markets to propose and implement projects of their choice as long as there’s minimal acceptance from the crowd. It is worth noticing that although its rationale is seen as more egalitarian and concerned with the democratization of access to funds and markets (Galuszka and Brzozowska, 2016), crowdfunding may reinforce superstar effects (Doshi, 2014; Barzilay et al., 2018), or concentration of funds in specific categories (Breznitz and Noonan, 2020). Despite the benefits related to alleviating policy management and transaction costs through dispersed funding, one can rightfully question if crowdfunding reinforces unstructured initiatives overly based on consumer sovereignty principles, hence reducing government monopoly (Towse, 2005). In this case, a set of coherent cultural policy (as a set of programs for the arts) may partially lose its relevance. In crowdfunding, public choice becomes more dispersed than any centralized governmental mechanism, thereby promoting creative projects whose quality criteria and credibility signals are equally dispersed.

On the other hand, the profusion of cultural projects and art forms in crowdfunding is expected to be more diverse and, therefore, adherent to the population’s interests. In the contexts of western democracies where cultural policies face legitimacy issues for failing to address diversity and new forms of organization in artistic fields (Mangset, 2020), one can question the extent to which centralized decision-making processes can deliver the goals of diversity in the arts. If sectorial policies remain restricted within institutional “iron cages” (DiMaggio and Powell, 1991), one can expect the crowd’s rule to rightfully open novel avenues for more diverse projects, and geographically-spread innovation in the cultural sectors.

The engagement of institutional supporters in private platforms does not mean that stable cultural policy is discarded. On the contrary, matchfunding is a powerful alternative for state-centric decision-making and over-dependence on “expert” positions regarding cultural decision-making (Mollick and Nanda, 2016). Ultimately, matchfunding is expected to work better in situations when the final decision remains with the crowd of independent donors whose small contributions resemble a democratic voting system (Mazza, 2020) and are combined with a centralized funding decision - either from a public or a private institution whose additional donations convey both credibility signals and extra monetary support to unknown creators. Yet, as previously explained, this assumption may be more of an expectation than an actual result of this online dispersed donation system.

Conclusion

Public and private initiatives have been historically entangled (Wagner, 2014; Wagner, 2016). It would be surprising if this phenomenon was absent in the contemporary platform economy. The matchfunding case exhibits a double-sided situation in which independent market actors and dispersed individual donors actively engage in making culture more widely available. In addition to that, public or private institutions (foundations, public sector, corporations) confer credible signals to both creators and the online platform responsible for matchmaking all involved actors. This synergy demonstrates that economic agents are not isolated within their institutional domains. The traditional dichotomy between government and market is thus replaced by a more relational mechanism aided by online tools in which dispersed communities and individual citizens are actively included in decision-making.

Private initiatives may reveal more “public” attributes than expected, hence diminishing the power of anti-private narratives often found in cultural policy research (Srakar and Čopič, 2012). This seems to be the case with matchfunding as this sophisticated mechanism is fully equipped to allow one-citizen-one-vote strategy via monetary contributions with tax-exempt options—if conditions apply. Instead of interpreting matchfunding as a purely private alternative, we can better make sense of its relevance from its public good attributes enhanced by digitalization: low-entry barriers, low excludability and low rivalry for donors, creators, and the institutional donors. Paradoxically, this private-based mechanism may deliver what public initiatives are traditionally expected to deliver: a diverse pool of cultural projects representative of a diverse population. It remains to be seen if matchfunding can fulfill such promises as its barriers seem to be the overall access to crowdfunding platforms and the interest in partaking a model when citizens are already high-taxpaying contributors. Nevertheless, the strong demand-testing component and public good attributes of artistic projects in crowdfunding lead us to believe that, given sufficient conditions, matchfunding may become a powerful tool for cultural policymakers in areas where centralized decision-making is out of reach, namely, the direct opinions of citizens. Among all forms of mixed funding strategies, online matchfunding appears to be a harmless one, with low risks to all involved parties.

We unveiled the main benefits of matchfunding also from an informational perspective: it reduces the transaction costs involved in planning, deciding, and implementing policies. From the creator point of view, the costs involved with preparing a subsidy, loan and other traditional philanthropic demands are also reduced. The simplicity of this scheme is, however, often accompanied by a lack of clear thematic choice and a lack of long-term financial sustainability for the creator. This is the area where matchfunding deserves more attention: 1) for creators, the support for creating relevant, high-quality projects is vital; 2) for policymakers, the awareness of the funding criteria and best-practices is relevant to ensure that long-term policy planning is not overrun by contingencies; 3) for online platforms, the challenge remains to transcend its matchmaking vocation towards aiding interest parties to create long-run sustainable mechanisms to support the arts. This article leaves some open questions for further research, namely: 1) what are the criteria used by governments for choosing platforms and potential projects online? 2) what is the current value of matchfunding in the scope of cultural budget and crowdfunding in general? and 3) how does the incorporation of a matchfunding budget in more extensive cultural policy directives come to being? This discussion yields various normative and positive debates not fully answered in this paper.

With the ever-growing crowdfunding model, we can assume that the future brings more matchfunding, hence demanding substantial scholarly attention to support practitioners in making this mechanism not only a short-term investment format, but part of thematic directives in the public sector. This is perhaps the biggest challenge, as thematic choices are restrictive in nature and, in contrast, crowdfunding projects vary enormously in their themes. The type of projects, the quality of creators and the purpose of projects must be ideally contrasted with pre-determined criteria which are yet to be established.

Finally, we questioned if matchfunding represents a consistent case for cultural policy 2.0: a policymaking strategy that is revamped by the crowd’s choices, open to diversity and sufficiently dispersed in its decision-making process. Reasonably, it urges that scholars delve into this model and trace comparisons with traditional funding strategies, and with typical non-matched crowdfunding in order to further build up best-practices, and case-based studies about the benefits and constraints of this model.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct, and intellectual contribution to the work and approved it for publication.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Footnotes

1See for example Miller and Yudice (2002), McGuigan (2004), and Gray (2007).

2Here we have used the word “donations” as matchfunding projects in the arts are often restricted to donation-based options with rewards offered in the form of memorabilia and public acknowledgement. Typically, crowdfunding campaigns in the arts select a “all-or-nothing” model, thereby implying that funds are only accessed by the project creator if the target goal is reached. For further comparisons between crowdfunding models, see Cummings et al. (2020).

3The decline of direct subsidies after 2008 for culture impacted small cultural entities and young professionals at the start of their careers. Independent and experimental projects then replaced staff with volunteers and further engaged in attracting private donors (Bonet and Donato, 2011). Nonetheless, this is not a universal rule. Norway, for example, has consistently increased its culture budget since 2005 (Mangset, 2020).

4For example, since 2010 the DCMS discusses matching grants with third-party investors to increase funds and promote a private sector policy for the arts (Stanziola, 2012).

5The authors show that the Spanish crowdfunding market has boomed after 2010 as a consequence of unemployment and recession. This explains the majority of solidarity campaigns in reward-based platforms in the country.

6National Endowment for Science, Technology and the Arts (NESTA); Department for Culture, Media and Sports (DCMS).

7We refer “screening” to Akerlof (1970) in reference to economic agents screening the product’s quality signals upfront, hence attempting to reduce the information asymmetry between buyers and sellers. Nonetheless, whereas, the information asymmetry problem results from agents actively conveying relevant signals to potential buyers, in our case, the public or private institution in charge of the matched funds will most likely perform a secondary screening, since the “crowd“s validation” comes first. As such, the quality signal is not conveyed by the creator of the project directly to the institution but it is mediated by the individual donor. In other words, if the project lacks quality but is still accepted by the “crowd of donors,” this would be a sufficient criterion for the matched institution. This unfolds important.

8The U-shape funding pattern shows that, especially in the reward-based model, contributions abound in the initial and later stages, but are considerably lacking in the development stage (Kuppuswammy and Bayus, 2017). Among other aspects, crowdfunding for the arts shows traces of high demand interdependence, close social networks (Dalla Chiesa and Dekker, 2021) and significant geographical proximity between funders and founders (Mendes da Silva et al., 2016).

9In some platforms—described later in this paper - when a project reaches 80% of the funding target, external funds will add to the crowd-based sum (Mondriaan Fonds, AFK, Kunstloc Brabant, and others). Therefore, the 70% limit depicted in the figure is merely illustrative. Typically, the platform decides which percentage of collected funds allows projects to incorporate institutional funds from other third parties. These decisions are taken in an agreement between the institutional partner and the platform that intermediates the funding process.

10A similar argument is developed by Srakar and Čopič (2012) about the fact that many so-called “private interventions in policymaking” are considered to be more public than private since agents may be driven by the intrinsic values of the arts or not retrieve clear use-values of their contributions.

11To the best of our knowledge, studies on evaluating the impact of advisory officers or learning materials for success rates are lacking in the crowdfunding literature.

12E.g., donation-based, reward-based, investment-based, and lending options. Each model provides different benefits to both creators and donors, hence different regulations apply.

13Recent figures estimate that supporters’ ages range from 14 to 35 years old (Fundly, 2020).

14Cultural organizations typically request formal permission for their donations to be tax-exempt. This process varies in each country where applicable. Since most crowdfunding initiatives start informally, we can expect that most projects run at the margins of formally institutionalized cultural provisioning.

References

Andreoni, J., and Payne, A. A. (2010). Do government grants to private charities crowd out giving or fund-raising? Am. Econ. Rev. 93 (3), 792–812. doi:10.1257/000282803322157098

Agrawal, A., Catalini, C., and Goldfarb, A. (2014). “Some simple economics of crowdfunding,” in Lerner and stern innovation policy and the economy (Chicago: University of Chicago Press), 14, 63–97.1

Akerlof, G. A. (1970). The market for lemons: Quality uncertainty and the market mechanism. Q. J. Econ. 84 (3), 488–500. doi:10.2307/1879431

ARTBUSINESS (2010). A private-sector policy for the arts. Availableat: http://artsandbusiness.org.uk/About/Our-history.aspx.

Baeck, P., Bone, J., and Mitchell, S. (2017). Matching the crowd: Combining crowdfunding and institutional funding to get great ideas off the ground. London: Nesta.

Bagwell, S., Corry, D., and Rotheroe, A. (2015). The future of funding: Options for heritage and cultural organisations. Cult. Trends 24 (1), 28–33. doi:10.1080/09548963.2014.1000583

Barzilay, O., Geva, H., Goldstein, A., and Oestreicher-Singer, G. (2018). Equal opportunity for all? The long tail of crowdfunding: Evidence from kickstarter. SSRN Electron. J. doi:10.2139/ssrn.3215280

Beckman, G. D., and Essig, L. (2012). Arts entrepreneurship: A conversation. Artivate 1 (1), 1–8. doi:10.1353/artv.2012.0000

Belleflamme, P., Lambert, T., and Schwienbacher, A. (2014). Crowdfunding: Tapping the right crowd. J. Bus. Ventur. 29 (5), 585–609. doi:10.1016/j.jbusvent.2013.07.003

Boeuf, B., Darveau, J., and Legoux, R. (2014). Financing creativity: Crowdfunding as a new approach for theatre projects. Int. J. Arts Manag. 16 (3), 33–48.

Bonet, L., and Donato, F. (2011). The financial crisis and its impact on the current models of governance and management of the cultural sector in Europe. ENCATC - J. Cult. Manag. Policy 1 (1), 4–11.

Breznitz, S. M., and Noonan, D. S. (2020). Crowdfunding in a not-so-flat world. J. Econ. Geogr. 20 (4), 1069–1092. doi:10.1093/jeg/lbaa008

Cacheda, B. G. (2018). Social innovation and crisis in the third sector in Spain. Results, challenges and limitations of ‘civic crowdfunding. J. Civ. Soc. 14 (4), 275–291. doi:10.1080/17448689.2018.1459239

Caves, R. (2000). Creative industries: Contracts between art and commerce. Massachusetts: Harvard University Press.

Cecere, G., Le Guel, F., and Rochelandet, F. (2017). Crowdfunding and social influence: An empirical investigation. Appl. Econ. 49 (57), 5802–5813. doi:10.1080/00036846.2017.1343450

Chang, J. W. (2020). The economics of crowdfunding. Am. Econ. J. - Microeconomics 12 (2), 257–280. doi:10.1257/mic.20170183

Chang, W. J., and Wyszomirski, M. (2015). What is arts entrepreneurship? Tracking the development of its definition. Artivate 4 (2), 33–31. doi:10.1353/artv.2015.0010

Čopič, V., Uzelac, A., Primorac, J., Jelinčic, D. A., Srakar, A., and Zuvela, A. (2011). Encouraging private investment in the cultural sector. Brussels: Policy Department Structural and Cohesion Policies, European Parliament.

Cumming, D. J., Leboeuf, G., and Schwienbacher, A. (2020). Crowdfunding models: Keep-It-All vs. All-Or-Nothing. Financ. Manag. 49, 331–360. doi:10.1111/fima.12262

Dalla Chiesa, C. D., and Dekker, E. (2021). Crowdfunding Artists: Beyond matchmaking on platforms. Socio-Economic Rev. 19 (4), 1265–1290. doi:10.1093/ser/mwab006

David, A. S. (1994). On justifying subsidies to the performing arts. J. Cult. Econ. 18 (3), 239–249. doi:10.1007/bf01080229

Davies, R. (2015). The jobs act: Crowdfunding for small businesses and startups. California: Apress. Davies, rodrigo. 2015. “Three provocations for civic crowdfunding. Inf. Commun. Society” 18 (3), 342–355. doi:10.1080/1369118x.2014.989878

Davies, R. (2015). Three provocations for civic crowdfunding. Inf. Commun. Soc. 18 (3), 342–355. doi:10.1080/1369118x.2014.989878

DE Voldere, I., and Zeko, K. (2017). Crowdfunding: Reshaping the crowd’s engagement in culture. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union.

Dekker, E., and Carolina Rodrigues, A. (2019). The political economy of Brazilian cultural policy: A case study of the rouanet law. J. Public Finance Public Choice 34 (2), 149–171. doi:10.1332/251569119x15675896589688

DI Maggio, P., and Powell, W. (1991). “The iron cage revisited: Institutional isomorphism and collective rationality in organizational fields,” in New institutionalism in organizational analysis. Editors D. M. Paul,, and P. Walter (The Chicago: University of Chicago Press).

Doshi, A. (2014). Agent heterogeneity in two-sided platforms: Superstar impact on crowdfuding. SSRN Electron. J. doi:10.2139/ssrn.2422111

Feder, T., and Katz-Gerro, T. (2015). The cultural hierarchy in funding: Government funding of the performing arts based on ethnic and geographic distinctions. Poetics 49, 76–95. doi:10.1016/j.poetic.2015.02.004

Frey, B. S. (1994). How intrinsic motivation is crowded out and in. Ration. Soc. 6 (3), 334–352. doi:10.1177/1043463194006003004

Frischmann, B. M. (2014). Infrastructure: The social value of shared resources. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Fullerton, D. (1991). On justifications for public support of the arts. J. Cult. Econ. 15 (2), 67–82. doi:10.1007/bf00208447

FUNDLY (2020). Crowdfunding statistics. Availableat: https://blog.fundly.com/crowdfunding-statistics/.

Gajda, O., Marom, D., and Wright, T. (2020). Crowdasset: Crowdfunding for policy makers. Singapore: World Scientific Publishing.

Galuszka, P., and Brzozowska, B. (2016). Crowdfunding and the democratization of the music market. Media, Cult. Soc. 39 (6), 833–849. doi:10.1177/0163443716674364

Garnham, N. (2005). From cultural to creative industries: An analysis of the implications of the creative industries approach to arts and Media policy making in the United Kingdom. Int. J. Cult. Policy 11 (1), 15–29. doi:10.1080/10286630500067606

Gong, N., and Grundy, B. D. (2019). Can socially responsible firms survive competition? An analysis of corporate employee matching grant schemes. Rev. Finance 23 (1), 199–243. doi:10.1093/rof/rfx025

Gray, C. (2007). Commodification and instrumentality in cultural policy. Int. J. Cult. Policy 13 (2), 203–215. doi:10.1080/10286630701342899

Handke, C., and Dalla Chiesa, C. (2022). The art of crowdfunding arts and innovation: The cultural economic perspective. J. Cult. Econ. 46, 249–284. doi:10.1007/s10824-022-09444-9

Hesmondhalgh, D., and Pratt, A. C. (2005). Cultural industries and cultural policy. Int. J. Cult. Policy 11 (1), 1–13. doi:10.1080/10286630500067598

Hetherington, S. (2017). Arm’s-length funding of the arts as an expression of laissez-faire. Int. J. Cult. Policy 23 (4), 482–494. doi:10.1080/10286632.2015.1068766

Josefy, M., Dean, T. J., Albert, L. S., and Fitza, M. A. (2017). The role of community in crowdfunding success: Evidence on cultural attributes in funding campaigns to “save the local theater”. Entrepreneursh. Theory Pract. 41 (2), 161–182. doi:10.1111/etap.12263

Katseli, L., and Boufounou, P. (2020). “Crowdfunding: An innovative instrument for development finance and financial inclusion,” in Recent advances and applications in alternative investments. Editors C. ZOPOUNIDIS, D. KENOURGIOS, and G. DOTSIS (Pennsylvania: IGI Global), 259–285.

Krebs, S., and Pommerehne, W. W. (1995). Politico-economic interactions of German public performing arts institutions. J. Cult. Econ. 19, 17–32. doi:10.1007/bf01074430

Kuppuswamy, V., and Bayus, B. L. (2017). Does my contribution to your crowdfunding project matter? J. Bus. Ventur. 32 (1), 72–89. doi:10.1016/j.jbusvent.2016.10.004

Lazzaro, E., and Noonan, D. (2020). A comparative analysis of US and EU regulatory frameworks of crowdfunding for the cultural and creative industries. Int. J. Cult. Policy 27, 590–606. doi:10.1080/10286632.2020.1776270

Mangset, P. (2020). The end of cultural policy? Int. J. Cult. Policy 26 (3), 398–411. doi:10.1080/10286632.2018.1500560

Marco-Serrano, F., Rausell-Koster, P., and Abeledo-Sanchis, R. (2014). Economic development and the creative industries: A tale of causality. Creative Industries J. 7 (2), 81–91. doi:10.1080/17510694.2014.958383

Mazza, I. (2020). “Political economy,” in A handbook of cultural economics. Editors R. Towse,, and T. Navarette (Cheltenham: Edward Elgar), 158–167.

Mendes Da Silva, W., Rossoni, L., Conte, B. S., Gattaz, C. C., and Francisco, E. R. (2016). The impacts of fundraising periods and geographic distance on financing music production via crowdfunding in Brazil. J. Cult. Econ. 40 (1), 75–99. doi:10.1007/s10824-015-9248-3

Michels, A., and Graaf, L. (2010). Examining citizen participation: Local participatory policy making and democracy. Local Gov. Stud. 36 (4), 477–491.

Mollick, E., and Nanda, R. (2016). Wisdom or madness? Comparing crowds with expert evaluation. Manag. Sci. 62 (6), 1533–1553. doi:10.1287/mnsc.2015.2207

Mollick, E. (2014). The dynamics of crowdfunding: An exploratory study. J. Bus. Ventur. 29 (1), 1–16. doi:10.1016/j.jbusvent.2013.06.005

Moysidou, K., and Hausberg, J. P. (2020). In crowdfunding we trust: A trust-building model in lending crowdfunding. J. Small Bus. Manag. 58 (3), 511–543. doi:10.1080/00472778.2019.1661682

Mulcahy, K. (2006). Cultural policy: Definitions and theoretical approaches. J. Arts Manag. Law, Soc. 35 (4), 319–330. doi:10.3200/jaml.35.4.319-330

Odorovic, A., Mertz, A., Kessler, B., Karaki, K., Wenzlaff, K., Araújo, L. N., et al. (2021). Unlocking the crowdfunding potential for the European structural and investment funds. European commission, DG REGIO. Available at: https://ec.europa.eu/regional_policy/sources/docgener/studies/pdf/crowdfunding_potential_esif_en.pdf.

Ostrom, E., and Hess, C. (2007). “A framework for analyzing the knowledge commons,” in Understanding knowledge as a commons: From theory to practice. Editors E. Ostrom,, and C. Hess (Cambridge: The MIT Press), 41–82.

Peacock, A. (2005). Public financing of the arts in England. Fisc. Stud. 21 (2), 171–205. doi:10.1111/j.1475-5890.2000.tb00022.x

Peacock, A. (2006). “The arts and economic policy,” in Handbook of the economics of art and culture. Editors A. Ginsburgh,, and D. THROSBY (Amsterdam: Elsevier), 1124–1140.

Rodriguez-Ricardo, Y., Sicilia, M., and López, M. (2018). What drives crowdfunding participation? The influence of personal and social traits. Span. J. Mark. - ESIC 22 (2), 163–182. doi:10.1108/sjme-03-2018-004

Rushton, M. (2008). Who pays? Who benefits? Who decides? J. Cult. Econ. 32 (4), 293–300. doi:10.1007/s10824-008-9083-x

Rykkja, A., Munim, Z. H., and Bonet, L. (2020). Varieties of cultural crowdfunding: The relationship between cultural production types and platform choice. Baltic J. Manag. 15 (2), 261–280. doi:10.1108/bjm-03-2019-0091

Senabre, E., and Morell, M. (2018). “Match-funding as a formula for crowdfunding: A case study on the Goteo.org platform,” in Proceedings of the 14th International Symposium on Open Collaboration (OpenSym ’18) (New York: Association for Computing Machinery).

Srakar, A., and Čopič, V. (2012). Private investments, public values: A value-based approach to argumenting for public support to the arts. Cult. Trends 21 (3), 227–237. doi:10.1080/09548963.2012.698552

Stanziola, J. (2012). Private sector policy for the arts: The policy implementer dilemma. Cult. Trends 21 (3), 265–269. doi:10.1080/09548963.2012.698564

Surel, Y. (2000). The role of cognitive and normative frames in policy-making. J. Eur. Public Policy 7 (4), 495–512. doi:10.1080/13501760050165334

Towse, R. (1994). “Achieving public policy objectives in the arts and heritage,” in Cultural economics and cultural policies. Editors A. Peacock,, and I. Rizzo (Dordrecht: Springer), 143–165.

Towse, R. (2005). Alan Peacock and cultural economics. Econ. J. 115 (504), F262–F276. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0297.2005.01005.x

Van Montfort, K., Siebers, V., and DE Graaf, F. J. (2021). Civic crowdfunding in local governments: Variables for success in The Netherlands? J. Risk Financial Manag. 14 (1), 8. doi:10.3390/jrfm14010008

Wagner, R. (2014). “Entangled political economy: A keynote address,” in Entangled political economy. Editors S. Horwitz,, and R. Koppl (Bingley: Emerald Publishing Ltd), 15–36.

Wehnert, P., Baccarella, C. V., and Beckmann, M. (2019). Crowdfunding we trust? Investigating crowdfunding success as a signal for enhancing trust in sustainable product features. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 141, 128–137. doi:10.1016/j.techfore.2018.06.036

Keywords: political economy, crowdfunding, match-funding, cultural policy, online platforms

Citation: Dalla Chiesa C and Alexopoulou A (2022) Matchfunding goes digital: The benefits of matching policymaking with the crowd’s wisdom. Eur. J. Cult. Manag. Polic. 12:11090. doi: 10.3389/ejcmp.2022.11090

Received: 02 July 2022; Accepted: 01 December 2022;

Published: 23 December 2022.

Copyright © 2022 Dalla Chiesa and Alexopoulou. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Carolina Dalla Chiesa, ZGFsbGFjaGllc2FAZXNoY2MuZXVyLm5s

Carolina Dalla Chiesa

Carolina Dalla Chiesa Andriani Alexopoulou

Andriani Alexopoulou