- 1University of Ferrara, Ferrara, Italy

- 2Minnesota State University, Mankato, MN, United States

- 3University of Chittagong, Chittagong, Bangladesh

- 4Social Responsibility and Economics, Katholieke Universiteit Leuven, Leuven, Brussels

The paper analyses the socioeconomic and environmental changes in the Rohingya refugee camp in Bangladesh. Bangladesh is one of the largest refugee host countries in the world. Due to the refugee inflow, Rohingya and host communities have been experiencing tremendous socioeconomic and environmental changes that hinder their sustainable life. Factors that have resulted in the camp area are market instability, cultivable land decline, pollution, deforestation, water and sanitation crisis, law and order failure, and drug use. All these changes accompany the refugee and host people’s discomfort and suffering. Moreover, some host people might feel unprivileged because they were not considered for relief schemes by donor agencies. A qualitative study was conducted to collect the data using the Case study and Key Informant Interview (KII) methods. Semi-structured interview schedules for the case study and open-ended interviews for the KIIs were used in this study. By illustrating the refugee and host’s socioeconomic and environmental dynamics, we tried to explain the current situation of the camp area. We also tried to shed light on the experiences of both communities regarding inclusiveness and building a cohesive society.

Introduction

Bangladesh is one of the largest refugee host countries in the world. It is home to more than 1.3 million Rohingya refugees and 166 million Bangladeshi people within 147,570 square kilometers (World Bank, 2021, 02–26). The state struggles to handle the large population, whereas tremendous pressures are on the land, food, water, sanitation, and environment. Simultaneously, after the independence in 1971, the demographic structure in Bangladesh changed partly because of the migration of Rohingyas from the Rakhine state of Myanmar. These displaced people have given Bangladesh a grave situation. The presence of refugees, at times, may contribute to the massive changes in the hosts’ social structure along with assorted troubles. For example, Tanzania experienced several significant changes and inconveniences after the arrival of refugees from Rwanda, Burundi, and the Democratic Republic of Congo (Whitaker, 1999, 5–18). Bangladesh might be facing similar issues.

Rohingyas started migrating to Bangladesh in the 1970s and 1980s. A notable migration took place in 1991 and 1992 when around 200,000 Rohingyas migrated to Bangladesh. Rohingyas who came to Bangladesh then have been living in two registered camps in Cox’s Bazar for the last three decades. In 2017 and 2018, nearly 700,000 Rohingyas arrived in Bangladesh. Now more than one million Rohingyas have been living in Ukhia and Teknaf Upazilas (Subdistricts) where Rohingyas are double the local people (European Commission, 2017, 1–2). Rohingyas have been living in 34 camps covering huge cultivable land and forest. The Bangladeshis administer the camps with the help of international agencies, especially the United Nations. However, Bangladesh has never signed any international convention or treaty to shelter refugees. Bangladesh sheltered Rohingyas on humanitarian grounds (Bashar, 2012, 10–13). Local people also accepted Rohingyas and supported them with homes, food, clothes, land, water, and sanitation when international communities were not there (Global Facility for Disaster Reduction and Recovery-GFDRR, 2018, 15–25). This openness to Rohingyas has impacted host communities’ socioeconomic and environmental resources, leading to discontent among them. The primary reaction comes from the labor market where Rohingyas sell their cheap labor affecting host peoples’ employment. Refugees may benefit hosts in many ways if refugees can sell labor to local producers to expand consumer markets and justify increased foreign aid. Therefore, accepting refugees may sometimes be part of the government’s broader development plan (Daley, 1991, 248–266). Nevertheless, some local people might have thought that refugee labor is a cost rather than a benefit. Bangladeshi host people think that the presence of Rohingyas adversely affects their life in many ways since they made the more significant section of the society unemployed with their cheap labor and extra working hours (Brac, 2017, 25–26). In Cox’s Bazar city, most of the manual and automatic activities are accomplished by Rohingyas which annoys the host laborers because Rohingyas are selling labor cheaply. Simultaneously, necessary daily grocery item prices have increased, albeit some items, e.g., rice, pulse, and oil are available at low prices. Some Rohingyas sell their relief items to the local market although development agencies (United Nations Development Programme-UNDP, 2018, 56–68) narrated that selling relief materials is illegal. Some local farmers become frustrated by the drop in the prices of beans, maize, and rice as refugees sell these items in the market (Whitaker, 1999, 5–18). Hospitals and health providers also face tremendous pressure, and sanitation has become a significant issue. Law and order decay because police and law enforcers do not have the resources to manage the large population. Sometimes, Rohingya groups get involved in militant and extremist activities in the camp area and kill and hurt fellow Rohingyas (Tamal, 2019, 1–2). It is also reported that a group of Rohingya youth instrumented with arms and deadly materials move around the camp and attack Rohingyas and locals if they find disagreements with them (Crimes in the Rohingya Camps, 2020, 4). Therefore, maintaining law and order is a significant challenge for security agencies in this area. The notable challenges, however, are related to the environment. Multiple environmental effects such as air and water pollution, landslides, cyclone, and flood, have already been experienced by the people in the camp area. The groundwater has already been depleted. Erosion of soil and terrain may cause landslides during the rainy season. Sewer sludge management and solid waste management are in critical condition. Local and Rohingya people directly or indirectly depend on nature for collecting firewood. Many host people living within the camps have already depended on government and international relief as they have nothing left to survive.

Very few empirical studies were conducted comprising the host and Rohingya communities’ socioeconomic and environmental changes. This paper aims to conduct a comparative assessment of the camp area’s socioeconomic and environmental changes to discern the communities’ bilateral relationship and inclusiveness. The findings may help future researchers and policymakers bridge refugees and hosts to build an inclusive society.

The theoretical framework

Malinowski’s cultural theory of needs is significant to understanding cultural integration. It emphasizes the cultural existence of society for meeting the individual’s basic biological, psychological, and social needs (Malinowski, 1944, 67–74). Every society is integrated into different cultural domains whilst these domains are linked by contemporary societal forms and functions. By form, Malinowski meant the social institutions that have multiple functions and are integrated into one another to respond to a variety of needs of the societal people. He outlined these needs into two main ideas, basic needs, and cultural responses. By basic needs, he meant metabolism, reproduction, bodily comfort, safety, movement, growth, and health. Some institutions are responsible for responding to basic needs. Every culture has the function of satisfying these biological needs for survival. To Malinowski, humans have, first and foremost, to satisfy all the needs of their organisms (Kohler, 1946, 126–128). On the other hand, he addressed commissariat, kinship, shelter, protection, activities, training, and hygiene as the cultural responses. The interaction between basic needs and cultural responses is significant to advance society and culture. The cultural responses to basic needs create new conditions, new needs, and new imperatives or determinants that are responsible for controlling human behavior. Therefore, any cultural integration of different cultural groups or people is needed to intake their basic needs and cultural response while maintaining their own identity. Every cultural group should be given chances to achieve their basic needs and cultural responses during integration. Malinowski advised host countries to set policies that would facilitate other groups’ cultural needs and responses. It can promote tolerance, respect, and trust towards other cultures and help to develop an integrated society (Algan et al., 2012, 11–15). He asserted to design of the host states’ institutions in a manner that can be able to accommodate cultural diversity. Cross-cultural contact generates behavioral changes that can dampen cultural differences and promote multiculturalism and social integration.

Several sociologists and anthropologists evaluated Malinowski’s cultural theory of needs while they also criticized it. Oscar (2012, 95–125) argued that the relationship Malinowski exhibited between basic needs and cultural responses is satisfactory. Because any cultural theory must be based on the organic needs which can relate to more complex imperatives called spiritual, social, and economic perspectives of society. He disagreed with the categories of basic needs since it is not exclusively biological as Malinowski called it. Parsons and Shils (1951) commented that Malinowski was the first to re-establish a connection between man as a biological organism and man as a culture creator by his need theory. Kempny (1992, 45–56) argued that the concept of basic needs is the part of ‘body of conditions’, which must be fulfilled if the community is to survive and its culture to continue. He also commented that the theory of needs is Malinowski’s weak point and highly criticized idea since he thought only singularly whilst there is a mutual interdependence between basic needs and culture.

Furthermore, the American Sociologist Williams (1947) first proposed that contact between members of different groups can reduce prejudice. Allport (1954) expanded this proposition from a socio-psychological perspective and emphasized that positive contact between members of two groups can reduce prejudice if contact happens under optimal conditions, i.e., cooperation, common goals, authority support for positive intergroup relations, and equal status within the contact situation. The effectiveness of intergroup contact to reduce prejudice is well established, as Pettigrew and Tropp (2006, 953–954) empirically observed in their meta-analysis of 515 studies. However, the meta-analysis showed that optimal conditions are facilitating but not necessary for contact to reduce prejudice. To develop integration among cultural groups, it is essential to contact the groups directly with one another (Hewstone and Swart, 2011, 375–376). By direct contact, Allport meant ‘face-to-face encounters’ among the members of different groups to reduce intergroup hostility. It is noteworthy that recent advancements in intergroup contact theory have underlined that contact needs to be experienced as positive to reduce prejudice because negative contact could instead increase prejudice (Barlow et al., 2012, 1629–1643). Also, recent research has suggested that despite contact opportunities segregation might persist and people might avoid intergroup encounters (Ramiah et al., 2015, 100–124).

Malinowski’s cultural theory of needs and Allport’s intergroup contact theory are significant to understand the Rohingya and host communities’ interaction and integration in Bangladesh. Malinowski emphasized the role of host institutions’ functions to regulate the basic needs, e.g., socioeconomic issues of the Rohingya people along with the cultural responses. Likewise, Allport stressed the contact among communities to reduce prejudice and misunderstanding (Tropp and Thomas, 2005). Positive contact between Rohingya and their host is essential to eradicate the prejudice and distance that persist between the communities. Both groups have different needs and cultural responses and the host community’s dissatisfaction with Rohingyas has intensified due to the socioeconomic crisis and environmental disaster. Therefore, the precondition of the integration between the communities is to ensure equal socioeconomic and cultural practices along with positive contact. The cultural theory of needs and intergroup contact theory can help us to understand the Rohingya and host communities’ interaction and foster positive integration between the communities to build an inclusive society.

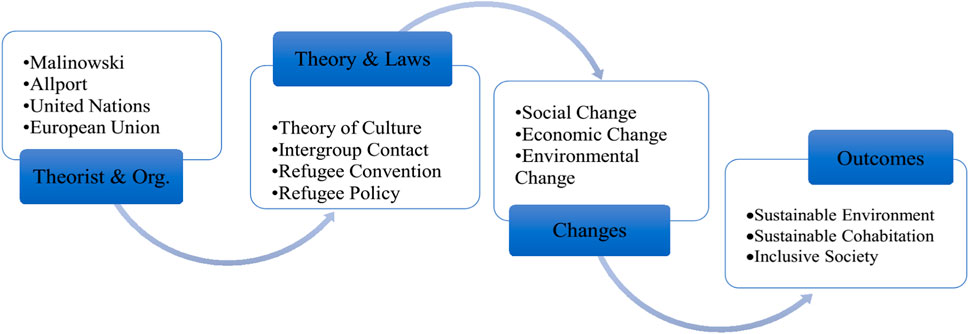

Moreover, the 1951 Convention about the Status of Refugees and its 1967 Protocol placed considerable significance on the integration of refugees and enumerated social and economic rights for the assistance of refugees. The European Union issued refugee integration policies based on the recommendations of the UNHCR by signing The European Parliament (1986). It emphasized the four significant policies including the free movement of people, services, goods, and capital to create a single European market albeit they limited the movement of individuals from the Third Country Nationals (TNCs). The Treaty of Amsterdam of the European Union (1997) set the policies for immigration and asylum and prioritized it as the first pillar. Article 63 of the treaty ensured policies of minimum standards for the grant or withdrawal of refugee status and protection (Sigona, 2005, 118–120). In addition, Robinson (1998) narrated the concept of integration as chaotic and vague since it results from the combination of several forces. Although integration is individualized, contested, and contextual, it’s not only a matter of host society and refugees, rather it involves many actors, agencies, logics, and nationalities. He mentioned that among these actors, NGOs can play a major role in shaping the national discourse on integration and refugee policies by acting as lobbyists, advocate, and implementing agents (Zetter et al., 2002, 98–105). Overall, institutional, organizational, and intergovernmental policies are needed to integrate refugees and build an inclusive society. In building an inclusive society with Rohingya and the host community in Bangladesh, national and international institutions and NGOs should coordinate with the Bangladeshi government to set policies. The theoretical frame of this study is given below (Figure 1).

Methodology

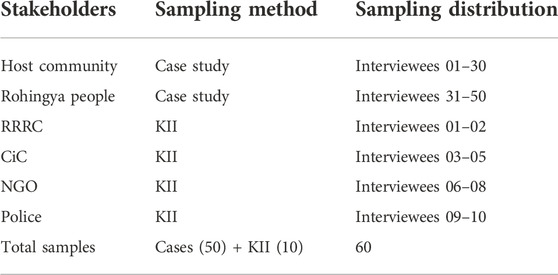

We conducted exploratory research to understand the socioeconomic and environmental changes in the Rohingya camp area. Several qualitative methods, such as the Case study and the Key Informant Interview (KII), were used by following the non-linear path and Grounded Theory (Punch, 1998, 123–126). The non-probability purposive sampling method was used to draw samples. The sample selection was performed according to the purpose of the study from the three main target groups, e.g., Rohingyas, the hosts, and the service providers. The service providers are the Refugee Relief and Repatriation Commissioner (RRRC) officers, Camp in Charge (CiC) officers, Non-Government Organization (NGO) officers, and the police. Samples were asymmetrically distributed; thirty (30) Cases were selected from the hosts, whereas twenty (20) Cases were collected from the Rohingyas. Furthermore, ten (10) KIIs were interviewed among the service providers, e.g., two RRRC officers, three CIC officers, three NGO representatives, and two police officers. These KIIs were significant in understanding the change inside the camp. A detailed distribution of the samples is shown in the Table 1.

Data were collected following the Case study protocol with a semi-structured interview schedule which is characterized by the flexibility of approach to questioning and does not follow a pre-determined system of questions. For the KIIs, the open-ended or non-structured interview schedule is used which allows greater freedom to ask, in case of need, supplementary questions or omit certain questions. In Case studies and KIIs, male and female respondents aged 18 to 50 were included. In this study, we did not record the respondents’ names and personal information because we were not interested in exposing respondents’ identities for security reasons.

Furthermore, the study was conducted in the Ukhia Upazila Rohingya camp and the nearby area. Ukhia refugee camp is well-known for the registered refugee camps and the habitat of the highest number of Rohingyas. According to the Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics (BBS, 2020, 8–11), around 300,000 hosts and 700,000 Rohingyas live in Ukhia. Data from Rohingyas were collected from camps 9 and 11, whereas the service providers’ data were collected at the CIC office of camps 9 and 11. The hosts’ data were collected from the West and East Balukhali villages in Palongkhali union (Grassroot administrative unit), the nearest area to the camp. Before conducting the study, the researcher repeatedly visited the study area along with the three research assistants trained in the study’s methods and concepts. After formulating data collection instruments, the researcher and three research assistants collected the data in the first and second weeks of June 2021. Finally, the recorded data were transcribed and analyzed into words.

Results

In this section, we illustrated the findings of socioeconomic and environmental issues that were collected from the Rohingya refugees, the host community, and Rohingya camp service providers. The findings are the local market instability, cultivable land decrease, stealing and robbery, criminal activity, and intergroup marriage. We also used secondary sources where it was required. Both empirical and nonempirical data are elucidated below.

Local market instability

The local people said that the local market turns out unstable after the Rohingyas’ arrival. The local market sells daily greenery and necessary items such as rice, fish, vegetables, dry fish (Shutki), and firewood. The prices have increased five times in the area after inflow. Earlier host people bought several fish at lower prices, e.g., Catla carp fish, Rohu Carp fish, and Mrigal fish for 300–350 BDT or 4 dollars per kilogram, but now prices have increased to around 500–600 BDT or 7 dollars. Furthermore, expensive fish, e.g., Hilsa, Shrimp, and Pomfret, are doubled their prices (Alam, 2018, 7–10). The prices of beef, chicken, and regular meats have increased three times. The daily grocery items, e.g., milk powder, chili powder, sugar, salt and garlic, onion, and turmeric, are hiked as the population becomes doubled and supplies are limited. In this situation, hosts and Rohingyas have to spend more money to buy staples. Every household experience a rising cost of living. An additional one million Rohingya people have created intense pressure on the supply chain and prices (Filipski et al., 2020, 8–10). The price rise has affected ordinary Rohingyas and host locals, albeit traders and producers are benefited from the Rohingya’s presence. Notedly, rice, pulse, soap, toothpaste, and cooking oil prices do not increase because Rohingyas sell these articles to the local market. The UNHCR and Humanitarian organizations distribute relief items, e.g., cereals, food grains, and other pieces of stuff that are sometimes in surplus (Khuda, 2020, 8–11). Therefore, they sell these extras to the local market, even though selling relief products is prohibited and illegal. Likewise, the regular price of one sack of rice in the market is around 3000–3500 BDT or 40 dollars, still, Rohingya people sell it for 1200–1500 taka or 17.5 dollars. Contrary, locals have no permission to sell relief products in their shops which they collect from the Rohingyas because the police, Border Guard Bangladesh (BGB), and military forbid them. Rohingyas agreed that prices of goods have increased in the market, and it is always unstable. They also added that at the beginning, there was pressure in the local market since Rohingyas bought their necessary articles from the local market. However, now they are under a relief scheme and they do not need to buy from the market except green vegetables, fish, and meats. Hosts complained that they are not allowed to set up shops or any permanent settlements near Rohingya camps for security concerns albeit Rohingyas are allowed to build shops or infrastructure. They found it a discriminatory attitude of the security personnel to them. The research team noticed a “Rohingya market” beside the camp where Rohingyas are the buyers and sellers. They sell relief articles in the market. The language between Rohingya and locals is identical; therefore, it is hard to identify “who is Rohingya and who is the host.” From the investigation, we found that different structures and shops set up by the Rohingya are illegal and do not have licenses. Even they do not pay taxes to the government since they do not bear any legal documents. The hosts argued that security forces and law enforcement agencies do not forbid them because they fear the international media and journalists.

Moreover, the hosts opined that the labor market seemed much more unstable in Cox’s Bazar district. The wage of the local laborers has dropped in half after the inflow (50%) because Rohingyas sell cheap labor in the hosting area. They leave the camp silently to seek short-term jobs in nearby cities, e.g., Ukhia, Teknaf, and Cox’s Bazar. A significant number of the hosts are day laborers and work in the agricultural field. After the government’s requisition of land and hill for camps, poor local laborers have become workless. The camps covered 60% of the cultivable land of the hosts and 40% of hills and government-reserved forests (Brac, 2017, 25–26). Earlier, poor laborers worked in agricultural lands and forest hills to earn around 500 taka or 6 dollars daily. It has depressed by 50% since the land is squeezed, and Rohingyas sell labor cheaply. Rohingyas work in hotels, motels, restaurants, shops, vehicles, and boats in Cox’s Bazar city and Saint Martin Island (2OO Rohingyas Caught Fleeing Bangladeshi Camps by Boat, 2019, 3). Several Rohingya mobile vendors were seen on Cox’s Bazar Sea beach and Saint Martin Island during data collection. They escaped from the camp, and they are not even listed. This situation impacts the local people’s income and living. Poverty incidence during the post-influx period is recorded higher in Ukhia and Teknaf than the national average of 24% (Making Rohingya Settle Down, 2021, 4). In the pre-influx period, impoverished people worked, gardened, collected firewood from the forest, and cultivated their land. However, they have been compelled to leave all those income-generating works due to building makeshift in this area because camps occupied all lands and forest hills. A Rohingya leader (Interviewee 31) expressed his opinion about the Rohingyas’ escape from the camp and seeking work outside the camp:

“It is impossible to work outside the camp as we are not allowed, which is strictly fostered by the military, Border Guard, Bangladesh (BGB), and police. It’s also true that some people may work in the city by escaping from the camp, but it's complicated.”

Cultivable land and Rohingya camp

The host people said that cultivable land and agricultural production curved in the host area after the influx since lands are acquired for camps, government buildings, and NGO offices. In the past, there were forests and hills where people collected wood and leave for fire. There were rivers where people caught fish and sold it in the market. Fishing was the primary income source for livelihood. Around 28% of employment came from fishing activities, e.g., shrimp cultivation, dry fish preparation, and hatching (Responding to the Rohingya Emergency in Bangladesh, 2020, 4–7). There was a ban on fishing from August 2017 after the influx, and around 30,000–35,000 fishermen became jobless, seriously affecting their annual income. The yearly income of the local fishermen was 40,000 taka to 90,000 taka ($470–1058) but suddenly dropped due to the ban. Moreover, host families are poor, and they depend on the cultivation of rice. Rice is a prominent grain for food. Numerous families produced extra rice to sell in the market to maintain their family expenses. Some families were also engaged in banana gardening. They could survive on the income that came from the banana garden. Many locals bred domestic animals, e.g., chickens, cows, and goats, and grazed cows and goats on the field. By selling these animals, they would collect their livelihood. Now they are compelled to pull up these activities due to a shortage of land in the post-influx period. Host communities’ former cultivable land is at present the Rohingya camp (Xchange, 2018, 35–37). A tremendous loss occurred for the poor daily laborers who worked in the field of others, cut paddies, and sold labor to the rich and landlords. Agriculture has completely shut around the camp area. Hills and fields have moved under the camp, and the host people have stopped farming and cultivating.

Many locals stated that there are some lands around the camp unusable due to contamination and pollution, particularly by human waste and camp trash. No multi-purpose drainage system surrounds the base, and the garbage, dirt, and debris directly come to the abandoned land. On average, 2–3 acres of land are covered by camp waste, although RRRC officers disagreed about the land size (Sattar, 2021, 1–3). Furthermore, some cultivable land was provided to Rohingyas when they first arrived and started living in the yard and bare space of the host people, which is later occupied for building the Rohingya camp. A crowd of hosts complained against Rohingyas for grabbing their land, though we couldn’t collect concrete documents. We talked to government officials, and they informed us that many applications about the locals’ land grabbing are still under analysis. An NGO officer (KII 6) refused this allegation against Rohingya and said:

“Rohingyas have no scope to occupy the land of others as they live in the camp. Of course, most of the camp is built on the land of host people, private and reserved forest, which Rohingyas echoed too.”

The researchers found that the CIC office is another stakeholder that captured the hosts’ land to build offices. Government and NGO offices are set on the land of the host people. During the establishment, government officers committed to recruiting at least two members from every host family for the camp job. However, they did not keep their promise and did not recruit any members from the hosts. The locals informed that many agitated hosts attempted to break down the government offices to evacuate their land, but government officials requested them to wait. The CIC office did not ignore it and assured that they recruited several local people in the office, and the process continued. Even many NOGs appointed host people in their offices. We met up with some host males and females working inside the camp and they denied the help of the RRRC and CIC office.

Stealing and robbery

Multiple stakeholders reported that stealing and robbery have increased in the camp area in the post-inflow period. The CIC office and Rohingyas informed that some local and Rohingya youth get united to conduct this activity at night when there is not enough security inside the camp. Host and Rohingya youth committed many occurrences in Ukhia and Teknaf Upazilas (Uttom and Rozario, 2019, 5–6). Police and RRRC officers also echoed the same as they recorded several stealing and robbery cases whereas both Rohingya and locals were accused. Hosts stated that they frequently notice the occurrence of stealing mobile phones, household accessories, cows, goats, and chickens. Earlier, people grazed cows, buffalos, and goats on barren land at large, while currently, they have to continuously check whether it gets missed or someone takes them away. Rohingyas rejected the complaints against them and said they have no scope to steal animals from locals as they remain inside the camp albeit the CIC admitted that they have received a couple of complaints against Rohingyas. Multiple sources reported to the researchers that some Rohingya youth and children are used to stealing domestic animals and materials from the local people. It does not happen every day; only a small portion of Rohingyas may be involved in this activity.

The police reported that in recent years, some events of robberies took place in many villages, albeit the perpetrators were not identified. Local people said that the host and Rohingya youth might involve in robberies since Rohingyas and locals gradually get intimidated. The locals reiterated that some Rohingyas often visit the local houses and ask for multiple help and food, e.g., curries, vegetables, and dry foods, to locate the position of household items to steal in their flexible time. Hosts supposed that a few Rohingya women typically conduct these acts as they can visit the host family in the daytime. Sometimes the thief runs inside the camp and disappears. Once someone gets into the base, it is not possible to trace them anymore. Beyond that, there is no punishment for this offense and the CIC and other authorities are reluctant about the issue. However, the Rohingya people ignored the accusation and also agreed that some might be involved in these activities with the local people. Hence, credit primarily goes to the host people. Both the communities requested the CIC, RRRC, and other authorities to be more active during the night and act against the perpetrators.

Criminal activity and social unrest

The host people confirmed that there is an increase in criminal activity compared to the past, mainly due to the presence of Rohingya criminals and extremist groups. Local people live in fear and panic as several Rohingya rival groups are involved in conflict with one another inside or outside the camp. The RRRC and security forces are also concerned as fractions among the rival Rohingya groups have increased. A police inspector (KII 9) stated:

“Rohingya criminal and extremist groups become active in the evening after office work. In the meantime, they committed several deadly incidents among themselves.”

He also asserted that extremist groups move inside and outside the camp near the hosts to create panic among the mass refugees and hosts. Rohingya people reported that if someone goes against the interest of extremist groups, they forcibly take them away and punish them according to their Islamic rules. At least ten extremist groups, e.g., Arakan Rohingya Salvation Army (ARSA), Rohingya Solidarity Organization (RSO), Master Munna Gang (MMG), Islami Mahaj, Nabi Hussain Dacoit Gang (NHDG), and Pakistani Taliban (TTP), are actively operating inside and outside the camp (Rohingya Militants Active in Bangladeshi Refugee Camps, 2019, 3–4). Rohingya and hosts are panicked by the behavior of the criminal groups. A host (Interviewee 4) narrated the situation: “Whenever we stay outside the home for work, we become worried about our families as the houses surround Rohingya camps.” He also argued that it might not be true that all Rohingyas are involved in illegal activity and make mischief to the hosts’ families and property. However, criminality in this area has increased dramatically during the post-migration of Rohingyas. The conflict between locals and Rohingya has also increased. Sometimes disputes and contentions take place for a simple cause. Many conflicts occurred between two ethnic groups to cause “hassle” among children. A CIC officer (KII 3) said: “Tension has increased between Rohingya and Host, and they set forth intolerant.” The host people stated that Rohingyas are united and camp administration sometimes works in favor of migrants.

Refugees and hosts agreed that another serious crime that takes place in the camp and hosts’ area is the drug business. Most of the conflicts are because of this drug. Hosts illustrated that drug is a gigantic and profitable business in Ukhia and Teknaf Upazila. The dealers are both Host and Rohingya. Hosts and Rohingya youth are getting involved in different criminal activities and hiding in the camp. A host (Interviewee 10) stated:

“A few months ago, security forces rescued million dollars of gold from the camp earned by robbery from different areas of Bangladesh.”

He also said that locals use Rohingyas as a medium to traffic drugs, especially the “Yaba tablets” from Myanmar. Both Rohingya men and women are involved in transferring drugs from Myanmar to Bangladesh and supplying them to different areas of Bangladesh. It is said that Rohingya women can perform better than men in dealing drugs and Yaba. Some innocent Rohingya women do this job for money and security. The study found that locals and Rohingyas work together in Yaba and the drug trades. Even many Bengali youths are involved in emotional relations with Rohingya women and girls, abducting and forcing them into prostitution. Rohingya girls are trafficked to Cox’s Bazar city hotels, motels, and cottages in the beach area. Some local people get married to Rohingya girls and collect “Birth certificates” and “Passports” to exit Bangladesh to go abroad together. An RRRC officer (KII 1) said: “We investigated some cases of Rohingya trafficking while arresting many culprits.” while an NGO worker (KII 7) mentioned: “Rohingyas and locals formed a secret team to traffic women. Sometimes, Rohingya woman agrees to go abroad for a better life.” Bangladeshi security forces identified several cases of entering fake marriages by Bengali people with Rohingya girls so that collection of documents from government offices becomes easier. However, intercultural marriage is not a regular issue and the chances are not so high. A Rohingya man (Interviewee 35) living in the camp agreed and narrated: “Criminal activity, drug business, and intra-group conflict increased inside the camp.” But he ignored the involvement of women and girls in drugs and prostitution.

Local youth and intergroup marriage

The host people informed that they notice a behavioral change in youths in the post-influx period. They believed that it happens due to the breakdown of the social system and decaying morality among youths. Host youths are busy after the inflow as an alternative income source is created for businesses, e.g., supplying gas cylinders and installing shops. Similarly, some youths are engaged in illegal drug businesses, e.g., selling Yaba tablets. Myanmar-originated Yaba is not new for Bangladeshi people, but its availability and accessibility have increased whilst Rohingya people started to import it. Host youths take this chance and become drug dealers and users (Crimes on the Rise in Cox’s Bazar Camps, 2018, 4). Different agencies in the camp area ensured us that the supply of Yaba tablets has increased during the post-influx period, and many Rohingya gangs are involved in this business. Host youths also get involved in this business by making friends with Rohingya gangs and using drugs. Locals stay inside the camp while taking drugs. Local and Rohingya youths supply Yaba tablets to host people. Local senior citizens (Interviewee 15) said: “90% of the youth have become schizophrenic or crazy in getting drugs and Rohingya women. They left their long-cherished culture and tradition.”

They also argued that some even get involved in trafficking drugs to big cities, e.g., Dhaka and Chittagong. An intracultural change takes place among the youth in the host area, and local parents and seniors cannot accept it. Many host people (Interviewees 17 & 18) mentioned: “They (the youth) do not follow the rules, regulations, customs of society nowadays though they were obedient before Rohingya arrivals.” A portion of host people believed that youths get attracted to young Rohingya girls in many ways, and are involved in sexual activities and marriage. An NGO worker (KII 8) said: “From the beginning, I have been working in the camp, and I did not find any case like this, though I heard about it.” The local police said that there are many cases recorded, and it is due to the exchange between the ethnic communities.

Ahmed (2019, 12–15) said that many outsiders come into camps and get married to Rohingya women, and take them away to Chittagong and Dhaka. Later they forcibly get involved in prostitution. Sometimes host people get into marriage with Rohingya women. Local people informed that many marriages were accomplished secretly between the communities. Some previously married locals get married to Rohingya women again because it is effortless and does not need any document or government registration. Local people believed that Rohingya-Bengali marriage may intensify in the future if protective measures are not taken. The host admitted that marriage between the ethnic groups creates a disturbance, instability, and domestic violence in host and Rohingya families. Sometimes, many married men divorce their wives because of Rohingya women and girls. Some Rohingya women conduct sexual activities for money and sometimes get married to foreigners and even migrate to developed countries. Host people sometimes mediate between outsiders and Rohingyas to traffic Rohingya women seeking migration. In such a way, several Rohingya women were trafficked from the camp and sold abroad (Ahmed, 2019, 12–15). All these situations have impacted the host and Rohingya families.

Host and Rohingya people anxiously appealed to the government and security forces to handle the drug dealers. They thought that the government should investigate and stop criminal activities. The unemployed Rohingya youth bring drugs from Myanmar and sell them to the camps and host area. On the other hand, many jobless young hosts get involved in the drug business and marry Rohingya women who are tempted by money and resources. If this turpitude runs, the innocent host and Rohingya will suffer in the long run. A local (Interviewee 20) reported:

“A married host with two children involved in a relationship with a Rohingya woman and married her without the permission of his first wife. His family had huge domestic violence, and now he has to maintain both wives.”

Most of the Rohingya people did not agree with the arguments of the locals about the Rohingya women’s involvement in prostitution and seduction. In their view, if this occurs, the ratio is abysmal. Rohingya people cannot go outside the camps without the permission of the government office. Furthermore, there might have been some cases of marriage between the host and Rohingya, and it’s exclusively by choice of individuals, not the community sentiments.

Life in the camp and its impact on the environment

The Host people said that the Rohingya camp plays a significant role in the life of the people in this area. The regular movement has become restricted for both Rohingyas and hosts, and no one can move freely. Individuals of both communities have mandatorily to bear identity cards during their stay outside. This situation creates discomfort in the local community. Both communities severely suffered from different issues, whilst psychological misery is beyond imagination. The overall situation has become a social, economic, cultural, and psychological pressure for the hosts and Rohingyas (Gebrehiwet et al., 2020, 3–5). In the post-inflow period, local people have experienced several accidents and deaths, which is the highest in the last 15 years. Roads are damaged for running big trucks and lorries to carry food and materials for the Rohingyas. Rohingya people drive different wheelers and cars to transfer materials and goods.

There are also major environmental issues as nature has lost its balance due to deforestation, pollution, and population density. The temperature has increased in the camp area compared to the nearest Upazilas. Hosts and Rohingyas face tremendous heat and climatic change around the camp area (Rahman, 2018, 113–125). Dust covers the whole area during summer, resulting in different respiratory diseases among locals and Rohingyas. Loss of biodiversity, forestland, and endangered wildlife are consequences of deforestation and pollution. A local (Interviewee 21) said:

"A thousand acres of forestland cleared for refugee camps. Every year the Rohingya and hosts people suffer and die because of landslides, floods, and cyclones.” A CIC officer (KII 4) explained: “In the last three years, around 50-60 events of monsoon-triggered landslides, floods, and cyclones took place in the camp where more than 20 Rohingyas died.”

The hosts opined that local people have lost their nature-based resources and livelihood due to deforestation and forestland clearance. An RRRC officer informed us that the development agencies are implementing several projects for rapid forestation and alternative cooking technologies such as LPG Cylinders, Cookstoves, Biomass briquettes, and biogas. Groundwater shortage is a vital problem for the people, although it was not severe before the influx. Thousands of swallow tube wells have been set up in the area at different slopes in the camp, resulting in excessive water withdrawal from the shallow aquifer and drying up the groundwater. In the meantime, many tube wells have already dried up and pondered the groundwater crisis. The crisis becomes deep during the summer and winter seasons. The water service providers are examining the possibility of a deep-water level; of course, it has no green signal yet (Department of Environment, 2019, 55–62). Simultaneously, groundwater contamination is a significant concern to the experts in this area of the cause of leakage, seepage, and overflow. Thousands of non-functional latrines and tube wells contaminate water. The experts of the Environmental Department of Bangladesh examined that 70% of the groundwater in the camp area is polluted. Groundwater depletion and contamination are the critical impacts of the Rohingya influx (DoE 201 55-62). Many hosts and Rohingya people mentioned that the water level got down and numerous tube wells are dysfunctional. A Rohingya woman (Interviewee 36) said:

"We must bring water from a half kilometer away as all the tube wells around our house are unused and non-functional."

Both Rohingya and hosts reported that surface water is also contaminated in the camp area. Ponds and small-scale streams are the sources of surface freshwater in this area. The authorities cannot manage the huge water demands of the Rohingya and host people. Both communities contaminate surface water through open defecation on the banks of ponds and streams. The sedimentation deposited in the stream is also the reason for the deteriorating water quality and surface water contamination. Furthermore, poor waste management in the camp area is affecting the environment. This area has no unified solid and liquid waste management and drainage system. Therefore, wastes are drained to the hosts’ surface water and maiden land. The main waste materials that pollute the environment are polythene, kitchen garbage, food packaging materials, batteries, and plastic bottles, contributing to climate change. Due to a shortage of firewood, numerous families use plastic as cooking fuel, damaging the environment. A Rohingya man was collecting plastic bottles to use for cooking. A host woman was also gathering firewood from the camp area for cooking. Likewise, the experts said that the landslide is a dangerous and potentially severe natural threat to the host and Rohingya. Due to cutting hills for building makeshift, the terrain lost its natural setting, and the vegetation cover of the landscape has already been removed. Weak soil structure contributes to erosion, and topsoil and other loose soils are highly susceptible to being blown away in the rainy season and stormy winds. Erosion has already blocked the passage, and hilly streams and risky hill-cutting may cause landslides in the camp at any time. In the rainy season, soil’s minerals are drawn away and kept into the mud, which is the cause of slides in the camp area (DoE 201 65-70).

Moreover, the impact on the forest and environment is immense. Around 60% of the forest land was chopped for making makeshifts, and the rest was also deforested due to the firewood collection (Imtiaz, 2018, 10–15). The monthly firewood demand for a single Rohingya family is 151 kg, while the mean family size is around 7. The total monthly requirement of firewood collected by Rohingya from the nearest forest is 6,800 tons. The host people also consume similar firewood from the forest. Around 90 percent of forest land will be cleared within a 10 km buffer zone if firewood is collected at the current rate in 31 months. Moreover, Asian Elephants are becoming critically endangered due to this influx. According to the International Union for Conservation of Nature (The International Union for Conservation of Nature-IUCN, 2020, 38–41), 40 elephants have been trapped on the west side of the Rohingya camp near the Myanmar border. Furthermore, the impact on the ecosystem is immeasurable, especially on wildlife, vegetation, marine, and freshwater ecosystems.

Discussion and conclusion

The findings of the paper predominantly illustrated the socioeconomic and environmental changes in the camp area after the inflow. These changes have affected both communities whilst they also face several unwanted inconveniences, e.g., drugs, crimes, and extremist activities inside and outside the camp. The socioeconomic (basic needs) and cultural changes in the host area have impacted the host community’s contact with the Rohingyas. Overall, the presence of refugees generates positive and negative changes worldwide and Bangladesh is no exception. National and world communities have a consensus that the arrival of Rohingya refugees has strained the limited natural resources, local infrastructure, public services, local economy, and mass movements. Instead, it would be imprecise to state that refugee insertion is synonymous with the negative development of the host area. Rather we argue that the inefficacy of the state mechanism to deliver services, inadequate attention to the host people, extensive refugee-centric policies, discriminatory access to humanitarian reliefs, and uncertainty about the future are considered a barrier to lagging behind the host area and the increase of resentment among the hosts. These points are also considered barriers to the inclusive relationship between Rohingya and their hosts. Refugee and host relations become jeopardized if the host’s demand is overlooked or inadequately addressed by national and international agencies. To avoid making Rohingyas a scapegoat for the hosts’ rising tensions and by considering the overlong refugee crisis, we would like to suggest initiating comprehensive, integrated, and all-inclusive humanitarian and development policies that will incorporate both communities. The policymakers should follow Malinowski’s Cultural theory of needs which emphasised the basic biological, social, and psychological needs of individuals. Rohingya and locals should have indiscriminate biological, social, and psychological freedom with cultural openness. The cultural responses to the basic socioeconomic needs can create a new condition that may change both communities’ behavior for integration. Moreover, policymakers should also follow Allport’s intergroup contact theory implications to reduce prejudice and misunderstanding between Rohingya and the host community. Regular cultural exchange and contact can create cohesion, tolerance, and trust that can contribute to the integration and inclusivity between the communities. Apart from the theories, policy should be formulated by considering the Refugee Convention of 1951 which ensured the socio-economic and cultural rights of the refugees and believed that socio-economic assistance is the gateway to integration and inclusivity. We should also take into account the European Union policies of refugee integration. The EU policies secured the free movement of individuals of their members. Through the Amsterdam Treaty, the EU prioritized refugee immigration and asylum as their first pillar and corroborated refugee integration and protection. Furthermore, development agencies especially NGOs should play their role to set policies in the host country Bangladesh. Overall, integrated policies regarding relief and development programs in Bangladesh may contribute to releasing tension and building an intimate relationship between the Rohingya and the host community. Well-executed policies can guarantee socioeconomic and environmental sustainability and durable humanitarian assistance in Bangladesh that can contribute to building an inclusive society.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Ethics statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Professor Dr. Abdullah Al Faruque, University of Chittagong Ethics Committee, Bangladesh. The patients/participants “Rohingya refugees” were provided written informed consent by the main investigator MM to participate in this study. In addition, the data were collected respecting the GDPR rules ([https://gdpr-info.eu/](https://gdpr-info.eu/)) and stored accordingly.

Author contributions

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct, and intellectual contribution to the work and approved it for publication.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all the research participants from the Rohingya and host communities of Cox’s Bazar district, Bangladesh who contributed to this study. In addition, we are grateful to the Refugee Relief and Repatriation Commissioner (RRRC), Camp in Charge (CIC) of 9 and 11, NGOs, and Security forces in the Rohingya camp for their enormous support and cooperation.

References

2OO Rohingyas Caught Fleeing Bangladeshi Camps by Boat (2019). Dhaka tribune, 3. Available at: https://www.dhakatribune.com/world/south-asia/2019/12/17/myanmar-seizes-boat-carrying-173-rohingya (Accessed December 17, 2019).

Ahmed, K. (2019). Rohingya women and girls trafficked to Malaysia for marriage. Al Jazeera, 12–15. Available at: https://www.aljazeera.com/indepth/features/rohingya-women-girls-trafficked Malaysia-marriage-190507212543893.html (Accessed September 25, 2022).

Alam, M. (2018). How the Rohingya crisis is affecting Bangladesh and why it matters. The Washington Post, 7–10. Available at: https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/monkey-cage/wp/2018/02/12/ (Accessed September 25, 2022).

Algan, Y., Bisin, A., and Verdier, T. (2012). “Introduction: Perspectives on cultural integration of immigrants,” in Cultural integration of immigrants in europe (UK: Oxford University Press), 11–15. doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199660094.003.0001

Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics (2020). Bangladesh Statistics 2020 (updated). Dhaka, Bangladesh: Ministry of Planning, 8–11. Available at: https://bbs.portal.gov.bd/sites/default/files/files/bbs.portal.gov.bd/page/a1d32f13_8553_44f1_ (Accessed June 10, 2022).

Barlow, F. K., Paolini, S., Pedersen, A., Hornsey, J. M., Radke, R. M. H., Harwood, J., et al. (2012). The contact caveat: Negative contact predicts increased prejudice more than positive contact predicts reduced prejudice. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 38 (12), 1629–1643. doi:10.1177/0146167212457953

Bashar, I. (2012). New challenges for Bangladesh. International Center for Political Violence and Terrorism Research, Nanyang Technological University. Available at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/319141141_New_Challenges_for_Bangladesh.

Brac (2017). Impact of forcibly displaced Myanmar nationals influx on host community. Dhaka, Bangladesh: Brac University, 25–26.

Crimes on Rise in Cox’s Bazar Camps (2018). Dhaka tribune, 04. Available at: https://www.dhakatribune.com/bangladesh/nation/2018/09/01/ (Accessed September 01, 2018).

Crimes in the Rohingya Camps (2020). The daily star, 1–3. Available at: https://www.thedailystar.net/editorial/news/crimes-the-rohingya-camps (Accessed August 18, 2020).

Daley, P. (1991). Gender, displacement and social reproduction: Settling BurundiRefugees in western Tanzania. J. Refug. Stud. 4 (3), 248–266. doi:10.1093/jrs/4.3.248

Department of Environment (2019). Geospatial technology-based water quality monitoring system for Bangladesh. Dhaka, Bangladesh: Center for Environmental and geographic information services, 55–62.

European Commission (2017). “The Rohingya crisis,” in European civil protection and humanitarian aids. Brussels, Belgium, 1–2. Available at: https://ec.europa.eu/info/index_en.

European Union (1997). “The Amsterdam treaty of 2 October 1997,” in Luxemburg centre contemporay and digital history, CVCE. Editor F. Pappalardo (European Navigator). Available at: https://www.cvce.eu/en/education/unit-content/-/unit/d5906df5-4f83-4603-85f7-0cabc24b9fe1/bb4a9f06-34fc-41e1-b237-ccc7543dd9f6#.

Filipski, J. M., Rosenbach, G., Tiburcio, E., Dorosh, P., and Hoddinott, J. (2020). Refugees who mean business: Economic activities in and around the Rohingya settlements in Bangladesh. J. Refug. Stud. 34, 1202–1242. doi:10.1093/jrs/feaa059

Gebrehiwet, K., Gebreyesus, H., and Teweldemedhin, M. (2020). The social health impact of Eritrean refugees on the host communities: The case of may-ayni refugee camp northern Ethiopia. BMC Res. Notes 13, 182. doi:10.1186/s13104-020-05036-y

Global Facility for Disaster Reduction and Recovery-GFDRR (2018). Rohingya crisis 2017-2018: Draft rapid impact, vulnerability and need assessment. Report. The United States and Dhaka, 15–25.

Hewstone, H. M., and Swart, H. (2011). Fifty-odd years of inter-group contact: From hypothesis to an integrated theory. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 50, 374–386. doi:10.1111/j.2044-8309.2011.02047.x

Imtiaz, S. (2018). Ecological impact of Rohingya refugees on forest resources: Remote sensing analysis of vegetation cover change in Teknaf peninsula in Bangladesh. Eco Cycles 4 (1), 10–15. doi:10.19040/ecocycles.v4il.89

Kempny, M. (1992). Malinowski's theory of needs and its relevance for emerging of the sociological functionalism. Pol. Sociol. Bull. 97, 45–56. Available at: https://www.jstor.org/stable/44816942.

Khuda, E. K. (2020). The impact and challenges to host country Bangladesh due to sheltering the Rohingya refugees. Cogent Soc. Sci. 6 (1), 8–11. doi:10.1080/23311886.2020.1770943

Kohler, W. (1946). Reviewed works: A scientific theory of culture and other essays by bronislaw Malinowski and huntington cairns. Soc. Res. 13 (1), 126–128. Available at: https://www.jstor.org/stable/40982115.

Making Rohingya Settle Down (2021). The financial express, 4. Available at: https://thefinancialexpress.com.bd/views/making-rohingya-settle-down-1629129716 (Accessed August 16, 2021).

Malinowski, B. (1944). A scientific theory of culture and other essays. New York, USA: The University of North Carolina Press, 67–74.

Oscar, F. (2012). Towards a theory of culture. United States of America: Trafford Publishing, 95–125.

Parsons, T., and Shils, A. E. (1951). Towards a general theory of action. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. Original publication in 1951 1953 and Routledge in 2007.

Pettigrew, T. F., and Tropp, L. R. (2006). A meta-analytical test of the intergroup contact theory. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 90, 751–783. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.90.5.751

Punch, K. F. (1998). Research design in qualitative and qualitative research. Introduction to social research quantitative and qualitative approaches. Trowbridge, Wiltshire: The Gromwell Press, 123–126.

Rahman, M. Z. (2018). “Livelihoods of Rohingyas and their impacts on deforestation,” in Deforestation in the Teknaf peninsula of Bangladesh. Editors M. Tani, and M. A. Rahman (Springer Nature), 113–125. doi:10.1007/978-981-10-5475-4_9

Ramiah, A. A., Schmid, K., Hewstone, M., and Floe, C. (2015). Why are all the white (asian) kids sitting together in the cafeteria? Resegregation and the role of intergroup attributions and norms. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 54 (1), 100–124. doi:10.1111/bjso.12064

Responding to the Rohingya Emergency in Bangladesh (2020). British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC). Media Action Asia, 4–7. Available at: https://www.bbc.co.uk/mediaaction/where-we-work/asia/bangladesh/rohingya-lifeline (Accessed September 15, 2020).

Robinson, V. (1998). “Defining and measuring successful refugee integration,” in Proceedings of ECRE International conference on Integration of Refugees in Europe, Antwerp, November 1998 (Brussels: European Council on Refugees and Exiles).

Rohingya Militants Active in Bangladeshi Refugee Camps (2019). Deutsche welle, 3–4. Available at: https://www.dw.com/en/rohingya-militants-active-in-bangladeshi-refugee-camps/a-50490888 (Accessed September 24, 2019).

Sattar, Z. (2021). Rohingya crisis and the host community. The financial express (Bangladesh: Published by Policy Research Institute of Bangladesh), 1–3. Available at: https://thefinancialexpress.com.bd/views/reviews/ (Accessed October 28, 2021).

Sigona, N. (2005). Refugee integrations: Policy and practice in the European union. Refug. Surv. Q. 24 (4), 118–120. Available at: https://www.jstor.org/stable/45054046.

Tamal, M. M. (2019). Rohingya camp-e sasoshtra group. Ukhiya news, 1–2. Available at: http://www.ukhiyanews.com (Accessed April 10, 2019).

The European Parliament (1986)“Single European act (Resolution),” in Official Journal of the European Communities No. C7/105, Doc. A2-168/86. Available at: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/about-parliament/en/in-the-past/the-parliament-and-the-treaties/single-european-act.

The International Union for Conservation of Nature-IUCN (2020). Annual Report 2019, IUCN-2020-025 en. Gland, Switzerland, 38–41. Available at: https://portals.iucn.org/library/node/49096 (Accessed June 15, 2022).

Tropp, R. L., and Thomas, P. F. (2005). Relationships between intergroup contact and prejudice among minority and majority status groups. Psychol. Sci. 16, 951–957. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9280.2005.01643.x

United Nations Development Programme-UNDP (2018). Impacts of the Rohingya refugee influx on host communities. Bangladesh and the United States: UNDP, 55–68.

Uttom, S., and Rozario, R. R. (2019). Struggling Rohingya seduced by crime at refugee camps. Union of Catholic Asian News, 5–6. Available at: https://www.ucanews.com/news/ (Accessed May 09, 2019).

Williams, R. M., Jr. (1947). The Reduction of Intergroup Tensions. New York, NY: Social Science Research Council.

Whitaker, E. B. (1999). Changing opportunities: Refugees and host communities in western Tanzania. USA: The University of North Carolina, 5–18. Working Paper No.11, Published by Center for Documentation and Research.

World Bank (2021). Bangladesh systematic country diagnostic 2021 update. Dhaka, Bangladesh, 02–26. Available at: https://www.worldbank.org/en/country/bangladesh (Accessed July 7, 2022).

Xchange (2018). The Rohingya among us: Bangladesh perspective on the Rohingya crisis survey. Rohingya-survey. Dhaka, Bangladesh: Xchange Foundation, 35–37. Available at: https://www.humanitarianresponse.info/en/operations/bangladesh/assessment/xchange.

Zetter, R., Griffiths, D., and Sigona, N. (2002). “A survey of policy and practice related to refugee integration,” in Final report to European refugee fund community actions, Oxford Brooker University. 98–105. Available at: www.Brookes.ac.uk/schools/planning/dfm/

Keywords: Rohingya refugee, host community, socioeconomic development, environment, inclusive society

Citation: Mohiuddin M and Molderez I (2023) Rohingya influx and host community: A reflection on culture for leading socioeconomic and environmental changes in Bangladesh. Eur. J. Cult. Manag. Polic. 13:11559. doi: 10.3389/ejcmp.2023.11559

Received: 12 August 2022; Accepted: 04 April 2023;

Published: 02 June 2023.

Copyright © 2023 Mohiuddin and Molderez. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Mohammad Mohiuddin, bWhkbW1tQHVuaWZlLml0; Ingrid Molderez, aW5ncmlkLm1vbGRlcmV6QGt1bGV1dmVuLmJl

Mohammad Mohiuddin

Mohammad Mohiuddin Ingrid Molderez

Ingrid Molderez