Abstract

This paper discusses dramaturgy and artistic research’s evolving role in theatre education, focusing on the Master’s program in Theatre at Oslo National Academy of the Arts as a case study. Drawing inspiration from Richard Jochum’s ideas in “After Artistic Research,” the paper highlights the shift towards incorporating artistic research into the curriculum of art universities. However, it acknowledges the challenges in establishing a clear framework for artistic research within these institutions. The author argues that teaching and practising dramaturgy and artistic research in theatre academies have significant implications, marking a departure from traditional theatre education paradigms. The paper aims to contribute valuable insights and practical strategies to educators and practitioners involved in theatre education and artistic research, emphasising the importance of understanding and navigating the complexities of this evolving field.

“The object of artistic research is art. As artists we engage in research to become better at what we are doing, for the development of knowledge and methods (Lillja, 2021).”

In “After Artistic Research” Jochum (2020) rightfully contends that we have arrived at a time where we can begin to move past the epistemological questions of how we can define artistic research and begin to look at how we can incorporate it into our practice and integrating it in our curriculums. In recent years, the organisational restructuring of art schools and the integration of theatre academies in research universities has “transformed the (epistemological) status that art carries, receives, and exerts within the domain of knowledge production” (Jochum, 2020: 101). After artistic research, we are entering a mode of teaching where the importance of artistic research and reflective practice is the hallmark of art universities, Jochum argues. However, while art universities embrace artistic research in their strategy and vision of art education, many struggle to find a clear and common institutional, ideological, and cultural framework for artistic research. While Jochum’s argument is far from controversial, things are rarely as straightforward and unproblematic in the complex and paradoxical world of education management and curriculum development. The understanding of artistic research and its terminology is often loaded with ambiguity and dissension.

In this paper, following Jochum’s insights, I will argue that “doing” and “teaching” artistic research in our academies carries profound practical and theoretical implications, marking a significant departure from the established educational paradigm of theatre education and a shift toward an emerging paradigm grounded in artistic research. Exploring a specific case study, I will critically explore the intersection between dramaturgy and artistic research to discuss how we can handle the complexity of artistic research in theatre education. As a teacher, researcher, and educational leader with a history of dealing with these questions, I hope to contribute to the ongoing dialogue in theatre education and artistic research. For this investigation, I will employ the Master’s program in Theatre at Oslo National Academy of the Arts as a case study. By delving into the specific context of this program, I intend to share hard-earned insights and practical strategies that can benefit both educators and practitioners in the broader field of theatre education and artistic research.

Redefining theatre education after postdramatic theatre: embracing artistic collaboration and process-oriented dramaturgy

The central thesis of this paper is that contemporary dramaturgy and artistic research inherently recognise the crucial connection between thought and creation, as well as the interplay between theory and practice. Like dramaturgy, the theories of artistic research promote a culture of reflection and dialogue, aligning closely with the dramaturg’s role in fostering conversations and providing feedback within the creative team. This fosters a more exploratory approach to education and theatre-making, where artistic aims, processes, and results are thoughtfully contextualised and investigated.

In the context of dramaturgy, this shift in theory and practice aligns with the works of scholars such as Trencsényi and Bernadette (2014), Trencsényi (2015), Theresa Lang (2017), Szatkowski (2019), and Bleeker (2023), who discuss the role of “new dramaturgy” (Kerkhoven, 1994) and the heritage of the so-called “postdramatic theatre.”1 Since the development of postdramatic theatre (Lehmann, 1999), the traditional hierarchy governing theatrical components has shifted and greatly expanded. In this context, the primacy of text has waned, and other elements such as space, light, sound, music, movement, and gesture now share an equivalent significance within the performance process. In “Dramaturgy on Shifting Grounds” (2009), Hans-Thies and Patrick (2009) discuss these evolutions of theatre and performance within dynamic cultural contexts marked by the influence of new media technologies and the emergence of hybrid forms encompassing theatre, dance, performance, installation, exhibition, film, and media art. These radical changes, highly relevant to contemporary theatre education, are often driven by innovative production methods and new approaches to institutional dramaturgy. For Lehmann and Primavesi, “new dramaturgical forms and skills are needed, in terms of a practice that no longer reinforces the subordination of all elements under one (usually the word, the symbolic order of language), but rather a dynamic balance to be obtained anew in each performance” (Lehmann and Primavesi, 2009: 3). Moving beyond the narrow confines of the text-based theatre, they also underscore the challenges faced by contemporary dramaturgy, which encompass fostering creative collaboration, particularly between authors and directors, ensuring effective communication within interdisciplinary production teams, formulating innovative concepts, curating novel approaches within cultural institutions, and promoting unconventional forms of exchange and discourse.

In Doing Dramaturgy (2023), Bleeker expands these ideas, discussing the historical shift in the dramaturg’s role and aptly demonstrates how these new approaches can be developed into a process-oriented approach. Overall, Bleeker’s theory represents a shift from conceiving dramaturgy as a noun to conceptualising it as a verb, emphasising the practice of “doing dramaturgy” (Bleeker, 2023). Studying the emergence of dramaturgy from Gotthold Ephraim Lessing to late modernity, she rightfully notes that dramaturgy is historically closely connected to the privileged role of dramatic text in Western theatre. Still, Bleeker, 2023 also expands on Lehmann’s theory of postdramatic theatre, but in less prescriptive tones, to describe the shift in paradigms towards a more process-oriented approach to dramaturgy. Rather than viewing theatre as a medium primarily for representing pre-existing structures of meaning, such as dramatic texts, Bleeker’s theory of dramaturgy envisions theatre as dynamic spaces where meaning, form, and content evolve organically throughout the creative process and collaborative thinking-making. Arguing that Doing Dramaturgy “is not a matter of intellectual interpretation, or of having the correct answers to how to construct a performance, but of engaging with the complexity of creative processes, where this may also mean to complicate or problematize rather than to clarify,” (Bleeker, 2023: 6) describes creative processes as collective efforts of “thinking making,” with dramaturgs often playing a crucial yet non-directive role. Bleeker presents this dramaturgical approach and comprises seven distinct modes of engagement with the creative processes and performances as they unfold. She poetically labels these seven modes as speculating, analysing, feeding, articulating, questioning, creating conditions, and structuring. Taking on this approach to Doing Dramaturgy as a teaching method, I will contend that it entails focusing on what emerges through the collaborative process of creating and thinking with others (Bleeker, 2023: 57). In the following, I will discuss how Bleeker’s approach to dramaturgy shares several critical elements with artistic research. Both perspectives view artistic practices as ongoing, process-oriented explorations rather than static outcomes. Just as artistic research emphasises the investigative journey within art, this form of “new dramaturgy” (Kerkhoven) focuses on “doing dramaturgy,” thereby turning it into an action or a way of thinking rather than a fixed role in traditional production dramaturgy.2

Why are we discussing the intersection between dramaturgy and artistic research? At this very moment, a considerable shift is taking place. Most Performing Arts Schools across Europe are transforming significantly, reinventing their educational paradigms for Bachelor’s, Master’s, and doctoral degrees. Examples of this development can be seen in the strategies and curriculum developments of interdisciplinary academies such as Oslo National Academy of the Arts (KHIO), Iceland University of the Arts (IUA), The Danish National School of Performing Arts (DASPA), Zürich University of the Arts (ZHdK), Uniarts Helsinki (UH), Amsterdam University of the Arts (AHK), and Stockholm University of the Arts (SHK). Thus, we find ourselves at a practical and theoretical crossroads, and the path we choose to travel has profound implications for the future of dramaturgy and theatre practice. In summary, as artistic research gains prominence in various theatre disciplines, it enriches those fields. It expands and challenges conventional approaches to theatre practice and production dramaturgy, ultimately leading to more nuanced, thoughtful, and impactful theatrical productions and projects.

In “What is Artistic Research?” from 2010, Klein (2010) follows a similar mode of thinking, contending that research is not exclusive to science and that artists have also engaged in systematic and creative activities akin to research. Emphasising that art and science are two dimensions within the same cultural space, Klein describes the role of artistic experience as a mode of perception, highlighting its importance in artistic research. Klein argues that, unlike science, artistic knowledge is sensory, physical, and embodied, distinguishing it from traditional declarative knowledge. Following Klein’s thought, I will discuss the development of an educational model that fosters a critical dialogue between dramaturgy and artistic research. My experience teaching dramaturgy to theatre students (e.g., playwrights, actors, directors, dancers, light designers, etc.) for over two decades has solidified my belief that theory and practice can mutually inform and inspire one another. By teaching that theory and practice are deeply interconnected, we can empower students to take ownership of their learning process. In this approach to dramaturgy, students are encouraged not merely to consume theoretical knowledge but to apply it in their artistic processes actively. Like the Applied Theatre Studies program in Giessen, our approach to dramaturgy underscores the interplay between theory and practice. Here, theory emerges because of artistic practice, and in turn, practice is critically examined through the lens of theory. However, it’s important to note that our MA in Theatre program differs in several aspects. Firstly, the scale of our program is distinct from the renowned university education in Giessen, as we have only 8-14 students in the program. This smaller cohort allows for a more intimate exploration of the integration of theory and practice in the study of theatre. Secondly, our institutional setting primarily emphasises artistic practice and research. This encompasses various forms of knowledge, including sensory, physical, and embodied aspects, as highlighted by Klein. Thirdly, we strongly emphasise the individual artistic development of each student. While this approach demands significant time and effort, it is a highly rewarding task. To unlock artistic research’s potential, as Julian Klein, Efva Lilja, and Richard Jochum note, students and teachers need opportunities for in-depth work processes, risk-taking, experiments and research that do not necessarily culminate in a product–such as a theatrical performance.3 As a place for learning and research, theatre academies can offer students and teachers the time for research-based processes, providing a laboratory for collective thinking-making and peer-based dialogue.

Artistic research, as discussed by Lilja, Klein, and Jochum, can be described as a practice-based or practice-led exploration undertaken by artists who aim to enrich knowledge about artistic processes and production through their investigations within art. Artistic research employs artistic methodologies, with the findings presented as works of art–these could manifest as performances, concerts, exhibitions, written works, or a fusion of various media. Accompanying this presentation of findings is detailed documentation and reflection on both the process and the outcome, providing a comprehensive insight into the entire journey of artistic exploration. In recent years, educators from various theatre disciplines, such as acting, directing, sound design, and choreography, to name a few, have found new ways to incorporate artistic research into their pedagogy and bring new methodologies and perspectives into the dramaturgical process.4

The following reflections aim to engage in the ongoing conversation about these issues and to provide a blueprint for instructing dramaturgy and artistic research methodologies. Specifically, I will examine the approaches employed within the curriculum of the Master’s program in Theatre at Oslo National Academy of the Arts, using it as a case study. I do not intend to assert that this model can be universally applied, but rather, I seek to offer insights and potential strategies that may be valuable to the broader discourse on this subject.

Rethinking the curriculum: KHIO’s master in theatre as a case study

The master’s program in Theatre at Oslo National Academy of the Arts (KHIO) is a two-year, full-time program tailored for individuals with a bachelor’s degree in Theatre or equivalent education and experience.5 Its primary aim is to provide students with a research-based and specialised education in acting, directing, writing, and dramaturgy, equipping them with the necessary knowledge and tools to collaborate, research and experiment. Within this discourse, let us delve into the institutional challenges this program encounters and illuminate how it occupies a position at the crux of the tension between the traditions of dramatic theatre and the emerging postdramatic paradigms.

In 1996, the Theatre Academy, which was initially formed in 1953, merged with four other academies and is now situated as one department within the interdisciplinary art academy (KHIO). The academy takes pride in its illustrious heritage, which is firmly grounded in the pedagogical principles of Konstantin Stanislavsky, further evolved by teachers such as Marija Knebel, Georgij Tovstonogov, and Irina Malochevskaja.6 This tradition is the foundation for its acclaimed acting and theatre direction programs at the bachelor’s level. The MA in theatre was formed in 2013, and during the subsequent years, a discernible gap emerged between the BA and MA programs. While the BA program remained committed to the Stanislavsky-based training, the MA program started to lean towards devised work and process-based approaches to dramaturgy, gradually embracing a postdramatic mode of thinking. This development introduced a degree of tension within the academy, prompting a critical re-evaluation of the institution’s educational framework and its approach to artistic research.

First and foremost, assessing how the academy’s specialised focus on dramatic theatre (acting and directing), firmly rooted in the Stanislavski method, could be further developed through artistic research became crucial. Secondly, there was a desire to explore the integration and implications of non-representational methods from the postdramatic theatre. This critical move aimed to align with the progressive development seen in schools and programs such as The Norwegian Theatre Academy (Østfold University College), DasArts (Amsterdam University of the Arts), and, notably, the Institute for Applied Theatre Studies in Giessen, Germany. Drawing from my experiences as a dramaturg and educational leader who faced similar institutional tensions and curriculum development challenges at DASPA (from 2015 to 2021), as well as through my collaboration with the NORTEAS Schools, I find it evident that this debate mirrors the ongoing development and discussions in most theatre academies across the Nordic and Baltic countries.7

Within the complex institution of KHIO, it was also pertinent to acknowledge a political obligation to educate students who can work in a diverse spectrum of theatre, which includes both dramatic and postdramatic forms of expression. This strategic aim, however, gave rise to a noticeable division between the two educational levels, each following its unique approach to teaching and research. However, with the revision of the MA curriculum, there is a collective effort to bridge this gap.8

In the new 2023 curriculum, we aim to offer students the opportunity to specialise in various fields, including acting, directing, writing, and dramaturgy. This restructuring represents a significant organisational goal to expand and enrich these fields within the academy while fostering collaboration with many schools and programs I have mentioned above. In the Norwegian context, we face a significant challenge regarding interdisciplinary and stage design and composition. This challenge stems from the fact that the education for scenography is hosted within The Norwegian Theatre Academy (NTA), an institution with a pivotal role in training actors and stage designers in the expanded field. It is crucial to underscore that our institution maintains institutional and artistic collaborations with NTA, with students working together on theatre productions.

Within the discourse of theatre in Norway, a concerning narrative persists regarding the relationship or perceived competition between these two schools. NTA, which formed the first Scandinavian MA in scenography in 2015, is widely recognised for its ability to question conventional theatre practice and challenge normative ideas on the methods of acting and scenography within the context of theatre education.9 As noted by Camilla Eeg-Tverbakk and Karmenlare Ely this was done out of a “commitment to deepen the connection between theory and practice” (Eeg-Tverbakk and Ely, 2015: 11). For this reason, NTA is often linked with physical theatre and postdramatic methods, while KHIO is occasionally seen as firmly grounded in the traditions of dramatic theatre.10 By comparison, the MA in Theatre at KHIO was first offered in 2013 with a similar aspiration to expand on the connection between theory and practice, including a questioning of conventional theatre practice and production dramaturgy. Although there have been significant differences in the respective curriculums, I find the narrative of dramatic vs. postdramatic schools in Norway problematic and overly simplistic for several reasons. Firstly, despite their differences, both institutions share a deep commitment to contemporary theatre practice and artistic research, which–as we shall see–includes research into a wide range of issues, such as developing postdramatic methods for acting and collaborative methods for theatre direction.11 Secondly, this juxtaposition of dramatic and postdramatic methods tends to impede essential collaboration and the exchange of knowledge, which is crucial in a community of art schools with a relatively limited number of students and scarce funding for research. This is particularly worrisome in a prosperous country like Norway, which can boast a national academy of the arts offering 21 study programmes and a doctoral program in fine art, design, arts and crafts, opera, dance, theatre, and arts education. Unlike comparable partner institutions like DASPA, ZHdK, UH, AHK, and SHK, however, KHIO does not provide a comprehensive spectrum of theatre disciplines such as light design, sound design, and stage design. This limitation constrains the potential for artistic research and collaborative endeavours in our MA in Theatre–although we enjoy the privilege of interdisciplinary collaboration with our opera and dance departments. It’s important to note that this observation doesn’t imply that every institution should encompass all possible disciplines, as that would be an impractical and unsustainable expectation. However, given the relatively small number of students and teachers in light design, sound design, stage design, writing, and theatre directing, it underscores the need for cross-border knowledge-sharing and collaboration among these theatre schools and programmes.

A model for such institutional collaboration can be found within the MA in Comparative Dramaturgy and Performance Research (CDPR), offered by KHIO alongside the MA in Theatre. This initiative is strategically positioned to address the complexities brought about by “postdramatic theatre” (as described by Lehmann in 1999) and “the performative turn” [as articulated by Fischer-Lichte (2004)]. It forms an integral part of a broader network, including five European universities, all united in their endeavour to equip dramaturgy students with the knowledge and competencies necessary for the critical analysis of chosen issues within the realm of performing arts. The curriculum is designed to prepare students for the significant challenges that have shaped the performing arts field in recent years. These challenges, as Nikolaus Müller-Schöll has noted, encompass the expansion of the concepts of performance and dramaturgy, shifts in the role of the dramaturge, transformations in the relationship between art and research, and the growing importance of international and multidisciplinary collaboration.12 It is specifically designed for students who aspire to work in international and intercultural settings, such as festivals, co-productions, exchange programs, and various collaborations. My experience is that including students with diverse backgrounds and exchange between the five universities creates synergy between these master’s programs and enriches the educational experience, offering a diverse, interdisciplinary approach to theatre and performance studies.13

This brings me back to the MA in theatre, established in 2013, positioning itself at the crux of the debate surrounding dramatic and postdramatic theatre. From a dramaturgical standpoint, we can consider this ambition as a productive paradox. In the context of an academy with a strong tradition of Stanislavsky-based theatre, it may appear contradictory at first glance, but it also encapsulates a valuable insight. Specifically, it implies that postdramatic sensibilities influenced the aspiration to evaluate theatre education. However, there was also a determination to transcend binary thinking and challenge the dogmatic aspects of both dramatic and postdramatic theories. Such institutional paradoxes are often the most fruitful and stimulating, as they can encompass pertinent insights from both sides. It is interesting to analyse how established dichotomies, such as text/performance, dramatic/postdramatic, staging/devising, etc., can be discussed. Furthermore, it’s worth examining how these apparent contradictions can contribute to creating a more enriching and complex educational framework on various levels.

Several crucial questions and institutional paradoxes have come to the forefront in revising the MA in Theatre. These questions highlight the essential link between expanding students’ respective disciplines (e.g., acting, directing, writing, and dramaturgy), how they can work with artistic research, and their involvement in collaborative theatre endeavours. Furthermore, the curriculum has had to address the paradox between aiming for specialised education in theatre disciplines like acting, directing, writing, and dramaturgy and the ambition to question the norms and values of these disciplines in the light of contemporary theatre and performance art. While the former has a strong foundation in established techniques and methodologies, the latter requires a more experimental approach that encourages students to question, experiment, and engage critically with their respective disciplines and research questions.

Among these inquiries, one is particularly significant: What knowledge and methods do students need to fully grasp and integrate to contribute actively to meaningful artistic research? This question prompts students and teachers to reconceptualise learning, shifting from a static accumulation of information to an ongoing, dynamic interaction with and critical understanding of theatre practice. Ultimately, however, the overarching goal of this didactic shift is to empower students, enabling them to take ownership of their artistic development, not just as practitioners of their craft but as creators, thinkers, and facilitators of their artistic research. This empowerment is not limited to individual growth but extends to creating a diverse and vibrant community of theatre artists. While this aspiration is undeniably utopian, it must be acknowledged that it is not without its inherent demands. It requires technical resources and specialised skills in mentoring, feedback methods, and team building, necessitating a collaborative spirit that thrives on the synergy of diverse disciplines and artistic values. This endeavour is, in essence, a testament to the relevance of dramaturgy (as discussed above), which fosters the kind of “thinking-making” (Bleeker) that transcends the boundaries of conventional paradigms and strives for a richer, more profound exploration of the theatre arts.

Dramaturgy and artistic research

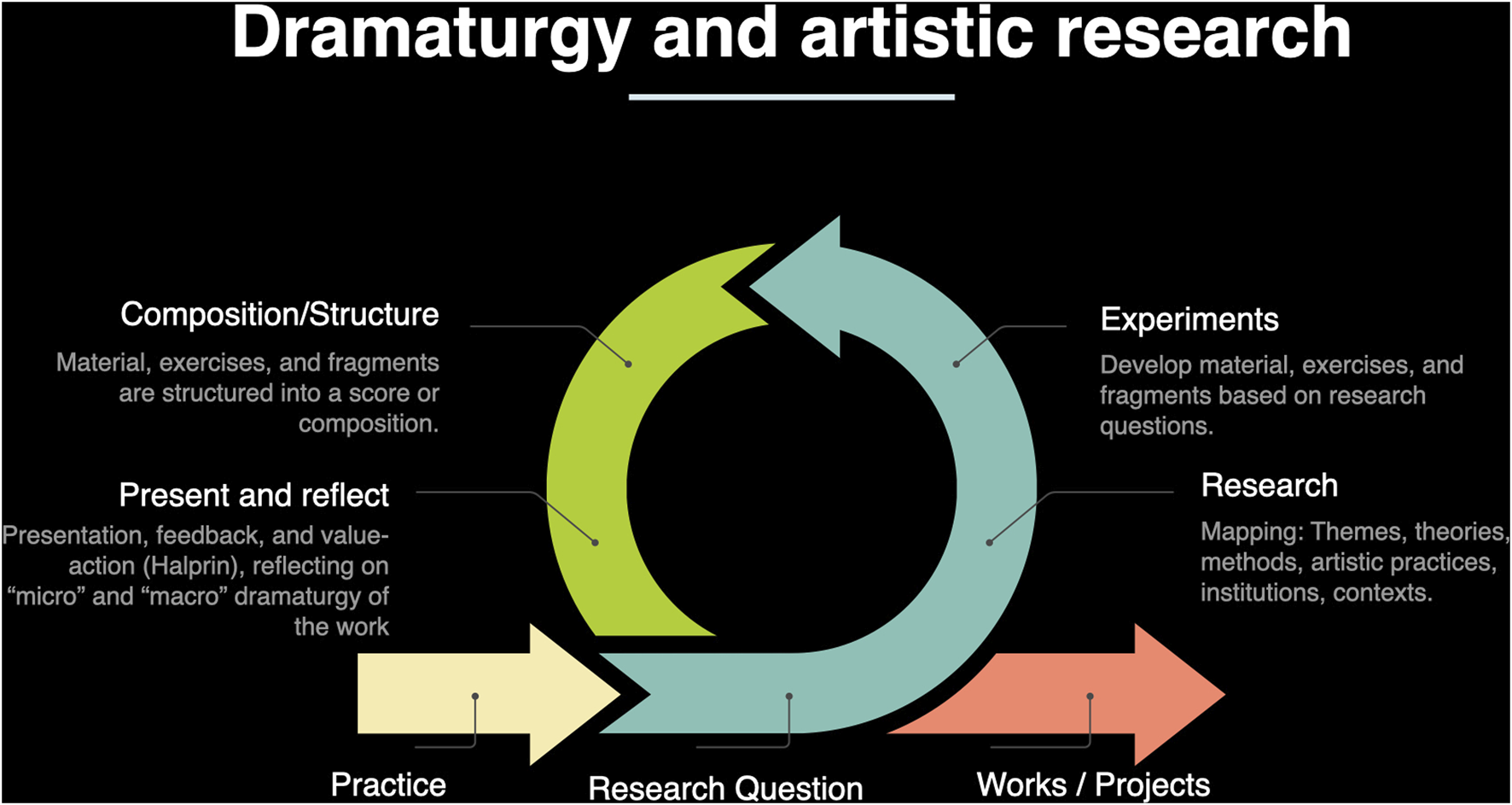

This leads us to our “dramaturgy and artistic research” course, which shapes the beginning of the programme. Students analyse and explore methods of production dramaturgy and process-oriented approaches to theatre and performance-making. In the following, I will utilize Bleeker’s seven modes of dramaturgical engagement to systematise how we work with the essential skills, knowledge, and mindset required to engage effectively with collective thinking-making. “Creative processes are instances of collaborative thinking-making in which dramaturgs participate,” Bleeker notes, adding that “dramaturg’s involvement does not usually start from one particular aspect of the creation or a particular expertise, such as dancing, costumes, acting, light, or sound” (Bleeker, 2023: 57). Unlike the dramaturgy I enjoyed teaching in the theatre schools in the late 1990s and early 2000s, which primarily centred on analysing plays and performances (based on a European canon of plays), this process-oriented dramaturgy aligns with the emerging concerns of postdramatic paradigms and emphasises the theoretical and methodological framing of students’ research and practice. See Figure 1, which provides a visual representation of our approach to dramaturgy and artistic research.

FIGURE 1

Dramaturgical model for research-based learning processes.

In the first year, students participate and collaborate in projects and dramaturgy courses alongside their chosen specialisation during both semesters. We aim to teach students to identify, appropriately select, utilise, and research artistic methods through theory and practice. In this feeding process, they are exposed to the thinking of various theatre traditions (e.g., dramatic theatre, epic theatre, physical theatre, performance art, postdramatic theatre) and artistic methods specific to their chosen specialisation–acting, directing, writing, or dramaturgy. It is a part of the ongoing discussion that we work on questioning our relation to and assumptions about these traditions and how they have been institutionalised in theatre education, including our own.14

In dramaturgical practice, Bleeker (2023: 64) highlights the close relationship between speculating and analysing materials and performances in their developmental stages. This part of the development process involves comprehending the inherent possibilities and considering potential dramaturgical implications and complexities of students’ projects. We observe artworks and processes to re-describe, analyse, and compare the poetics and values of various artefacts, including performances, texts, and production and reception processes. This critical reflection on poetics and values teaches the students to identify, apply and research methods for their artistic expressions and intentions. Following Bleeker, we can also consider that this analysing and contextualising feeds the students’ reflections on the implications of their projects (micro dramaturgy) and the cultural context of their work (macro dramaturgy). Even when the student’s projects do not explicitly relate to the traditions and context that inform them, their work inevitably shows traces of such contexts. These traces could, for instance, encompass the values, philosophical foundations, discourses, practices, and institutional conditions within which the students have undergone their training.15

On this theoretical background, students develop a theoretical framing for their research, which includes research into relevant topics, methods, and materials. The second year is dedicated to further honing their craft through exchanges and internships, culminating in creating and realising a master project based on their individual research questions. Coming from various backgrounds (most often acting, directing, stage design, and physical theatre), our students aspire to explore various approaches to theatre and performance, such as ritual theatre, the post-Anthropocene, autobiographical work, documentary theatre, and research-based writing. They are often driven by the possibility of generating novel ideas and knowledge across diverse fields and disciplines. These original insights and concepts emerge through research-oriented artistic practices that address specific research questions and evolve new methods, processes, and performances.

Articulating the ideas central to their projects is also part of how students communicate with their peers and the potential audience of their work. At the end of the MA, students must present their work to their peers within and outside the academy and the broader public. This necessitates thorough documentation and critical reflection, ensuring a comprehensive understanding of their artistic journey. This step entails contextualising the research question, with particular attention to the students’ artistic practices, chosen methods, relevant theories, and current developments in the field. Once the framework is in place, students engage in artistic experiments informed by their research question. The artistic research uses various methods, resulting in fragments and material that can take numerous shapes and forms, such as texts, images, light, sound, movement, and scenes. The contextualisation of their work is a fundamental pillar in cultivating a research-oriented mindset. It goes beyond mere experimentation in their respective fields, extending to the documentation and analysis of results. This approach to “doing” dramaturgy, as previously discussed, strongly aligns with Efva Lilja’s concept of “the artist as a researcher” (Lilja, 2018), who embarks on artistic research, asserting that art and artistic development are the focal points of their artistic research. In the role of actors, directors, writers, and dramaturgs, they primarily embark on research to enhance their artistic capabilities and understanding. Like Lilja’s artist-researcher, our students’ approach to “doing dramaturgy” demands a discerning eye for how their research and performances are influenced by or become interconnected with the current circumstances or context in which they operate. In essence, they learn to be attentive to how external factors impact their work and how their work, in turn, impacts the broader environment it exists within. This process-oriented approach should ideally involve questioning and experimental exploration within these contexts. From this perspective, dramaturgy emerges as a critical mindset, akin to Lilja’s artist-researcher, actively engaging with materials, audiences, poetics, and the role of art in society. In this light, the artist-researcher assumes the roles of both creator and observer, effectively bridging the realms of theory and practice.

Working on questioning, where students engage in dialogue to further the development of their projects and discuss the inherent possibilities of what is being created, gains depth and nuance when supplemented by artistic research methodologies. In this context, Bleeker’s concept of collaborative thinking-making emerges as a methodological approach for exploration and comprehension, aligning with our pedagogical model of theatre education, which inherently embraces collaboration and interdisciplinarity. Fostering constructive questioning and dialogue in a learning environment can be a challenge, especially when dealing with theatre students from diverse backgrounds and varying artistic interests and values. To address this challenge, we provide training in feedback methods (e.g., “critical response theory,” Lerman 2022; Borstel, 2018). Our approach to feedback methods is also profoundly influenced by our cross-border collaboration with teachers from DAS Theatre (Amsterdam University of the Arts). This theatre education, which specialises in research-based artistic practice and feedback methods, has played a pivotal role in bringing hybrid, cross-disciplinary artistic practices to the forefront of contemporary art discourse.16

This is all part of creating conditions for artistic research, which may sometimes require teachers to be “present and attentive” (Bleeker, 2023: 68), adopting the role of a supportive listener and observer of the student’s artistic practices and research. My approach to facilitating the process builds on a cyclical model, which incorporates research questions, frames, material, scoring, and presentation/evaluation. I draw inspiration from Lawrence Halprin’s seminal work, “The RSVP Cycles” from 1969. Developed in collaboration with dancer and choreographer Anna Halprin, the RSVP cycle emphasises “scoring” to make creative processes visible and facilitate participation. Halprin defines of “scores,” as a visual mapping “which describe the process leading to the performance” (Halprin, 2014: 42). Halprin’s work initially focused on exploring the notion of ‘scores’ and examining how they function across various artistic disciplines. Here, a ‘score’ refers to a drawing or visual representation of processes that unfold over time. While scores are commonly associated with music, Halprin broadens the definition to encompass ‘scores’ across all aspects of artistic practice, and his interest lies not in any single, fixed scoring system but instead in the broader concept of scoring to outline and visualise processes, experiences, and creative endeavours. Similarly, our approach to portfolio and documentation uses scoring to outline, analyse, and articulate the various elements of the artistic process, thereby aiding communication within artistic collaborations. Just as Halprin’s RSVP cycles offer a helpful framework for articulating and understanding creative processes, our dramaturgical model aims to clarify what is often implicit or intangible, facilitating a deeper understanding of artistic collaboration and the interplay of ideas and actions.

This model begins by tapping into students’ research questions, practical experiences, and assumptions about their work. This knowledge consists of their reservoir of skills, ideas, and experiences they might not have articulated, formalised, or fully realised. By initiating a dialogue with students, we start a discovery process and formulate a research question that directly resonates with their interests and experiences. For instance, a student might be interested in exploring documentary material, leading to questions about its development method and the ethics of staging it.

This dialogue is the initial stage in documenting and mapping tacit knowledge and artistic practice into a structured portfolio. As the dialogue continues, students gradually articulate and organise their skills, knowledge, and expertise in relation to a specific research question. This process helps them become conscious of dominant themes and questions in their artistic practice, effectively externalising these as research questions. This allows for self-reflection and growth and provides a framework through which their artistic practice can be understood, critiqued, and developed by themselves and others.

In line with Halprin’s method, the student’s material and scores are presented, evaluated, and reflected upon multiple times. This prompts us to analyse and discuss the structuring of their work, recognising tendencies and possibilities in the form and content of their work. Such evaluations consider the content and structure and the methods, experiments, inquiries, and decisions that led to the presented artistic results. These reflections on structuring often lead back to the research question, which may be refined and re-evaluated throughout the process. Following the final presentation, students create a portfolio and a critical reflection of their work. Ideally, this step can lead to publications and further dissemination of their work, assisting them in finding relevant peers and expanding their artistic practice.

This model highlights the cyclical aspect of artistic research and emphasises the importance of reflection and peer feedback. Encouraging students to evaluate their practice critically allows them to contribute to theoretical discourse, making them creators of knowledge rather than mere consumers. This fosters a reciprocal dialogue between theory and practice. As Lilja notes, the development of presentation and evaluation methods is crucial for generating new knowledge: “By developing my artistic work also as research. [it] can be criticised and reflected upon by the outside world” (Lilja, 2018: 71–72). Peer feedback and review are vital for nurturing research-based thinking in our educational programs, requiring what Lilja describes as “a critical mass of relevant competence” (Lilja, 2018: 70). In line with our goal of cultivating an environment of constructive criticism and peer-to-peer feedback, our students are trained in the Critical Response Process developed by Lerman and Borstel (2022). This pedagogical approach aligns seamlessly with our model and stresses the cyclical nature of artistic research and the vital role of reflection and peer critique. By employing Lerman’s framework, we equip students with a structured methodology for giving and receiving feedback, enabling them to contribute meaningfully to theoretical discourse. As emphasised by Lilja, the strength of methods for presentation and evaluation is pivotal in generating new knowledge. We aim to foster a two-way dialogue between theory and practice through structured feedback, enhancing the educational experience and promoting research-based thinking.

The question of what the research process entails when actors, directors, and writers also assume the role of dramaturg is at the core of this development. While Bleeker’s theory delves into the multifaceted role of dramaturgy, our teaching model aligns with a similar ethos, aiming to empower students to become creators, thinkers, and facilitators of their artistic research. For example, students with an education in acting might simultaneously work as writers and directors performing self-written texts. Others who specialise in theatre direction may depart from the authorial role of the director, focusing on developing devised work and collaborative processes. This raises an intriguing question within an educational context where students are forced to collaborate on their artistic work and integrate dramaturgical thinking into their artistic practice. What might the creative process entail if actors, directors, and writers themselves assume the multifaceted role of the dramaturg? How can they collaborate as a team? How can their roles develop and change during the thinking-making process?

As discussed above, recognising the collaborative nature of the creative process is essential for fostering effective teamwork and the growth of theatre professionals. This teaching approach fosters an environment where students learn from their creative endeavours and experiences. In essence, they are not just learning about dramaturgy but learning to work and think as dramaturgs themselves. Therefore, by giving students the autonomy to engage in their own critical reflections and creative processes, we encourage them to develop a more nuanced and comprehensive understanding of dramaturgy as both a theoretical discipline and a practical art form.

In contrast to Lehmann and Primavesi, who advocate for a thinking process that naturally evolves within “non-hierarchical groups” (Lehmann and Primavesi, 2009: 6), our experience has revealed that such collaborations can often be quite challenging when roles merge, shift, or become unclear during the process.17 As noted by Bleeker, dramaturgical sensibility and facilitation become even more critical in collective processes or devising, where responsibilities and roles are not always sharply defined. As a result, we have increasingly focused on the decision-making processes and how to ensure transparency for all participants, drawing inspiration from Halprin’s seminal work. Adopting the notion of “non-hierarchical” theatre in an uncritical manner, we are running a potential risk that the idealistic goal could deteriorate into confusion and conflict. This is especially true when students participate in creating each other’s research projects. As a result, participants may have different objectives, requiring dramaturgical sensibility and a solid ability to handle complexity. We find that students become adept at recognising that decision-making processes and hierarchies are not static entities but temporal processes where roles and decisions are renegotiated many times along the way. Interestingly, Halprin’s resource, score, presentation, value-action method, and mentoring and feedback methods (Lerman and Borstel) have proven valuable tools in navigating these dramaturgical challenges.

It requires a specific dramaturgical skillset to create conditions (as noted by Bleeker), creating and cultivating a space for such collaborations to occur meaningfully and productively. In the projects undertaken by our students, we often witness various individuals taking on dramaturgical tasks during the creative process. What is intriguing is that even when the formal position of the dramaturg diminishes in such projects (cf. Trencsényi, 2015: 163), the essential dramaturgical functions they typically fulfil, such as facilitating, generating ideas, articulating concepts, archiving the work, identifying emerging structures and meanings, making connections, and offering specialised knowledge, continue to play a vital role in this type of creative work. Additionally, it’s worth noting that this flexible approach to other roles, such as the actor, writer, and director, can also be observed in certain situations. Depending on the research question and the evolving creative process, these roles may shift during the process or be shared among team members, highlighting the adaptable and collaborative nature of these artistic endeavours. As these are all complex matters, dramaturgy becomes a method to handle this complexity and facilitate artistic research in a way that allows everyone to contribute to the process in a meaningful way.

Conclusion: redefining dramaturgy and artistic research in MA theatre education

In this paper, I have outlined and contextualised the curriculum and teaching of the MA in Theatre, which strongly emphasises reflective practice and artistic collaboration. Our proposed model can be seen as a case study for integrating dramaturgy and artistic research within theatre education, emphasising the cyclical and iterative process of theory and practice, honing skills through continuous exploration, experimentation, reflection, and refinement. By acknowledging and validating the students’ personal research questions, we aim to foster a teaching environment where their tacit knowledge can be articulated and critiqued. As such, we are shaping not just observers and interpreters but creators, directors, and facilitators of their artistic research. Ultimately, this transforms the understanding of dramaturgy within the academic setting and reshapes the broader landscape of theatre practice, marked by dramatic and postdramatic concerns.

By contextualising the curriculum and outlining the course on “Dramaturgy and Artistic Research,” I have discussed how this teaching model aligns with Bleeker’s theory of dramaturgy, fostering a mindset where students are encouraged to be not just practitioners of their craft but also active creators, critical thinkers, and facilitators of their artistic research.

I have tried to explain how we, as teachers, can support and mentor this development with relevant knowledge, engaging in critical examination and feedback on the students’ research questions, theories, and methods, encompassing their projects’ micro and macro dramaturgy. Through their research, students can discover novel concepts, allowing them to reconsider their roles in the process and the nature of their artistic work. This process allows them to engage in artistic collaboration, assume leadership roles, explore the relationship between performer and audience, explore innovative presentation formats, address political and societal concerns, and establish sustainable theatre practices. Ultimately, our educational endeavours are driven by a commitment to maintain the relevance of theatre as an art form in an increasingly complex and diverse society.

In my capacity as a dramaturgy teacher, I consider one of the most significant facets of this paradigm shift to be the incorporation of dramaturgical theories and models as essential tools for navigating the intricacies and complexities inherent in artistic collaboration and peer-to-peer feedback. While our BA programs in Acting and Directing are designed to nurture excellence in specific roles and skills, the MA in Theatre encourages students to transcend these boundaries and participate in collaborative thinking and practice. A theatre academy like ours should be able to strike a balance between specialisation and interdisciplinarity within its curriculum. This equilibrium should allow us to engage effectively with dramatic and postdramatic concerns.

Our theatre academy’s strategic objective is to establish a stronger connection between the two educational levels, thereby bridging the gap between the BA programs, which emphasise individual specialisation, and the MA program, which promotes collaborative and interdisciplinary approaches to theatre. This transition brings opportunities and challenges to the ongoing development of theatre education.18

As outlined in our MA curriculum, the intersection of “Dramaturgy and Artistic Research” is designed to endow students with practical competencies and theoretical insights, equipping them to craft meaningful contributions within theatre practice and production dramaturgy. Ideally, this pedagogical approach enriches the individual theatre disciplines, fostering a more profound and expansive engagement with dramaturgy. As educators, our role in this transformative process is pivotal. We guide and nurture students, encouraging them to explore and question their work’s “micro” and “macro” dramaturgy. In this endeavour, we aim to reshape the academic perception of dramaturgy and redefine its role within the diverse and multifaceted theatrical landscape.

Biography

By Mads Thygesen (1972), Professor in Dramaturgy at Oslo National Academy of the Arts (2022-), Associate professor in theatre practice and production dramaturgy (University of Aarhus, 2023-). Former rector of The Danish National School of Performing Arts (2015–2021) and rector of The Danish National School of Playwriting (2010–2015). Holds a PhD in Dramaturgy (2009). Member of the board of Dramaten (The Royal Theatre, Stockholm 2022-) and Oslo National Academy of the Arts (2023-).

Statements

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

All research and writing conducted by MT.

Funding

The author(s) declare(s) that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Acknowledgments

Important colleagues who have contributed to the development of the MA curriculum, as presented in the paper, include Jesper Halle, Anne Holtan, and Victoria Meirik.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Footnotes

1.^The concept of the postdramatic, which gained significant momentum in the early 2000s, is primarily due to the inner circle at the Institute for Applied Theatre Studies in Giessen (Andrzej Wirth, Hans-Thies Lehmann, among others), where the concept was introduced in a short article written by Andrzej Wirth for the university newspaper as early as 1987. However, the peak moment arrives only with Hans-Thies Lehmann’s influential Postdramatisches Theater from 1999, where the concept is given its most comprehensive development. Cf. Bernd Stegemann’s critical essay “After Postdramatic Theater,” in Theater (New Haven, Conn.), 2009, Vol.39 (3), p.11-23 (DURHAM: Duke University Press, 2009). DOI: 10.1215/01610775-2009-002. In his critical review of the heritage of postdramatic theatre, Stegemann contends that Lehmann’s aesthetic theory has shifted towards a more prescriptive stance within the theatre community, constraining artists from fully harnessing the compelling elements of theatre, such as characters and narrative storytelling.

2.^This shift has also been described by Theresa Lang, who, despite a more analytical approach, defines dramaturgy as “a mindset, rather than a function” and “as a way of seeing and communicating, a way of engaging with material and audiences, and ultimately a way of looking at the world” (Lang, 2017: 4).

3.^See Efva Lilja’s “The Pot Calling the Kettle Black - An Essay on the State of Artistic Research,” In: Huber (2021): Knowing in Performing (Bielefeld transcript Verlag, Bielefeld, 2021: 28–34).

4.^A compelling illustration of the intersections between artistic research and this new approach to dramaturgy can be seen in Yann Coppier’s “Absurd sounds” (Journal of Artistic Research, 2021. https://doi.org/10.22501/jar.820939). Coppier’s research interrogates conventional methods of engaging with sound by employing absurdity as an innovative tool. While the scientific fundamentals of sound are rarely questioned in various sound-related fields, Coppier’s project challenges these underlying assumptions. By actively questioning or even rejecting established norms (e.g., considering silence as a construction tool for musical composition), the research follows a unique methodological path that shares similarities with conspiracy theories: it starts with an absurd premise and logically develops it to uncover new techniques, ideas, or art forms. This approach exemplifies the type of questioning and innovation encouraged in both artistic research and new dramaturgy.

5.^Cf. https://khio.no/en/studies/academy-of-theatre#masters-in-theatre

6.^In the Scandinavian context, these methods have served as a significant foundation for the training of actors and directors, notably at The Theatre Academy (KHIO) since 1994. Cf. Irina Malochevskaja: Regiskolen (translated by Hans Henriksen and Sverre Rødahl, Tell, Vollen 2002). It is also worth noting, however, that the school was also influenced by the teachings of Rudolf Penka, who visited and taught a system for actors based on the synthesis of Brecht and Stanislavski in the 1970s.

7.^Cf. NORTEAS is a Nordplus network of Nordic and Baltic Performing Arts institutions in higher education. NORTEAS encourages students and teachers to seek innovation and new approaches to the already established practices through exchanging knowledge, experience and visions on contemporary performing arts and education. http://www.norteasnetwork.org. KHIO is also committed to collaboration with other networks for knowledge exchange and internationalisation, including: https://alexandrianova.eu, https://www.ecoledesecoles.eu.

8.^To me, this development also honours the continually evolving work of Stanislavsky, whose artistic method was marked by a commitment to experimentation, science, and research. See, for example, Jonathan Pitches: Science and the Stanislavsky Tradition of Acting (Routledge, Abingdon, Oxon 2006) and Mel Gordon’s The Stanislavsky Technique (Applause Theatre Book Publishers, New York 1994).

9.^Cf. Camilla Eeg-Tverbakk and Karmenlare Ely: Responsive listening–theatre training for Contemporary Spaces (Brooklyn Arts Press, United States 2015).

10.^In Karmenlara Ely’s essay “Yielding to the Unknown: Actor Training as Intensification of the Sense” (Eeg-Tverbakk and Ely, 2015: 15–33), there is a notable exploration of how the legacy of postdramatic theatre is examined and contemplated in actor education. Eeg-Tverbakk highlights that “postmodern dramaturgies” have been experimenting with form and challenging actors to rethink the dynamic space between the “self” and the “other” within the staging of a text or character (Eeg-Tverbakk and Ely, 2015: 17).

11.^Notable examples include Petra Fransson’s research in acting and postdramatic text. cf. Franssson’s Omförhandlingar: Kropp, replik, etik (Malmö Faculty of Fine and Performing Arts, Lund University (2018).

12.^Cf. Nikolaus Müller-Schöll’s introduction to dramaturgy and CDPR: https://dramaturginfrankfurt.de/macdpr/ (accessed 14.12.2023).

13.^The five CDPR universities are: Goethe University, Frankfurt/Main, Université libre de Bruxelles, University of the Arts Helsinki, Université Paris Nanterre, Oslo National Academy of the Arts. The program was initiated in 2017 following extensive discussions and meetings with various partners. The program’s inception involved collaboration with Nikolaus Müller-Schöll, Karel Vanhaesebrouck, Christophe Triau, Tore Vagn Lid, Esa Kirkkopelto, and Karoline Gritzner.

14.^We also incoporate Janek Szatkowski’s A Theory of Dramaturgy (2019) to analyse and contextualise research-based aesthetics. Adopting Szatkowski’s complex theory of second-order observations and his analysis of theatre artists and their poetics contribute significantly to our theoretical and practical exploration of dramaturgy.

15.^Adopting the distinction between micro (the individual production) and macro dramaturgy (cultural context) from Van Kerkhoven, Bleeker proposes that “Macro dramaturgical concerns are about how the larger social, historical, and cultural context, as well as the institutional conditions of making and showing, is intentionally or unintentionally implicated in the construction of performances” (Bleeker, 2023: 94).

16.^The primary objectives of DAS Theatre’s feedback sessions are as follows: to empower artists receiving feedback on their work, move beyond mere judgments, facilitate in-depth criticism, promote precision and clarity as a form of (self-) discipline, and ultimately enhance the satisfaction derived from both giving and receiving feedback. Cf. https://www.atd.ahk.nl/en/theatre-programmes/das-theatre/study-programme/educational-vision/ (accessed 14.12.203).

17.^In Dramaturgy in the Making, a similar point is made by Trencsényi (2015: 163), who studies how the dramaturg’s role can shift or even disappear in process-led dramaturgy.

18.^At the same time, we aim to prepare them for further study in KHIO’s doctoral program. Focused on hands-on, studio-centric artistic work, the department explores methods and concepts that further develop the expertise in acting and directing. On the Master’s and PhD levels, there is systematic experimentation in theatre art’s artistic, organisational, and contextual possibilities. Particular emphasis is placed on studying individual and collective strategies as mutually dynamic and creative challenges. The department currently hosts five PhD students and has two open positions for PhD in theatre direction

References

1

Bleeker M. (2023). Doing dramaturgy. Switzerland: Springer.

2

Borstel J. (2018). “Finding the progress in work-in-progress: liz lerman’s critical response process in arts-based research,” in Arts-based research in education. Editors BorstelC.TaylorS. (United States: Routledge), 212–227.

3

Eeg-Tverbakk, C. Ely K. (2015). Responsive listening – theatre training for Contemporary Spaces (USA: Brooklyn Arts Press).

4

Fischer-Lichte (2004). Ästhetik des Performativen. Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp.

5

Halprin L. (2014). The RSVP cycles: creative processes in the human environment. Choreogr. Pract.5 (1), 39–47. 10.1386/chor.5.1.39_1

6

Hans-Thies L. Patrick P. (2009). “ Dramaturgy on Shifting Grounds,” in Performance research14 (3), 3–6. (Routledge: Abingdon).

7

Huber A. (2021). Knowing in performing (Bielefeld: Bielefeld transcript Verlag).

8

Kerkhoven M. V. (1994). “Looking Without a Pencil in the Hand,” in Marianne Van Kerkhoven (ed.), Theaterschrift 5–6, On Dramaturgy, (Brussels, Kaaitheater), pp. 140–148.

9

Klein J. (2010). What is Artistic Research?. JJournal for artistic research, Society for Artistic Research, 2017. 10.22501/jarnet.0004

10

Jochum R. (2020). “After Artistic Research,” in Teaching Artistic Research. Editors JochumM-BMcNiffB (Berlin: Walter de Gruyter GmbH).

11

Lang T. (2017). Essential dramaturgy. England, UK: Routledge.

12

Lehmann H.-T. (1999). Postdramatisches theater. Frankfurt am Main: Verlag des Autoren.

13

Lehmann H.-T. Primavesi P. (2009). Dramaturgy on shifting Grounds. Perform. Res.14 (3), 3–6. 10.1080/13528160903519468

14

Lerman L. Borstel J. (2022). Critique is creative: the Critical Response Process in theory and action (Middletown, Connecticut: Wesleyan University Press).

15

Lilja E. (2018). “Beyond the ordinary on artistic research and subversive actions through dance,” in Tanzpraxis in der Forschung - Tanz als Forschungspraxis. Editors LiljaE.QuintenS.SchroedterS. (Bielefeld: Bielefeld: transcript Verlag), 63–72.

16

Lillja E. (2021). “The Pot Calling the Kettle Black,” in Knowing in performing. Editors HuberA. (Bielefeld: Bielefeld transcript Verlag), 28.

17

Szatkowski J. (2019). A theory of dramaturgy. London: Routledge.

18

Trencsényi K. Bernadette C. (2014). New dramaturgy. International perspectives on theory and practice (London: Bloomsbury).

19

Trencsényi K. (2015). Dramaturgy in the making. UK: Bloomsbury.

Summary

Keywords

dramaturgy, artistic research, art and culture institutions, education management, curriculum development

Citation

Thygesen M (2024) Navigating the intersection of dramaturgy and artistic research in contemporary theatre education. Eur. J. Cult. Manag. Polic. 14:12288. doi: 10.3389/ejcmp.2024.12288

Received

24 October 2023

Accepted

08 April 2024

Published

10 May 2024

Volume

14 - 2024

Updates

Copyright

© 2024 Thygesen.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Mads Thygesen, madsthyg@khio.no

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.