Abstract

The primary objective of this paper is to examine, both theoretically and empirically, two distinct approaches through which artistic research intersects with academia. This examination is undertaken to critically evaluate the paradigmatic tensions arising from the juxtaposition of unfettered artistic exploration and the escalating pressures for demonstrable outcomes, accountability, and process transparency inherent in managerial contexts. Consequently, the theoretical underpinnings of artistic interventions within organizational settings will be explicated, emphasizing the academic community’s exploration and application of such modes of artistic inquiry. Conversely, the approach of art-based research will be delineated, emphasizing its utilization of artistic modalities to investigate phenomena through a scientific lens. Moreover, prominent theories positing academic research as constraining artistic experimentation will be outlined. Finally, drawing upon four case reports conducted within academic environments, a novel method will be proposed to mitigate the encroachment of increasingly institutionalized approaches towards the arts.

Introduction

We want the same economic and practical means and possibilities that are already at the disposal of scientific research, of whose momentous results everyone is aware. Artistic research is identical to “human science,” which for us means “concerned” science, not purely historical science. This research should be carried out by artists with the assistance of scientists. The first institute ever formed for this purpose is the experimental laboratory for free artistic research founded 29 September 1955 at Alba. This type of laboratory is not an instructional institution; it simply offers new possibilities for artistic experimentation. The leaders of the old Bauhaus were great masters with exceptional talents, but they were poor teachers. […]. Our practical conclusion is the following: We are abandoning all efforts at pedagogical action and moving toward experimental activity Jorn, 1957.

The initial articulation of artistic research traces back to Asger Jorn, 1957, where it delineated the exploratory and experimental facets inherent in artistic endeavors, akin to those found in scientific inquiry. As observed by Cramer and Terpsma (2021), this conception implies that artistic research cannot be strictly categorized as a nascent or emerging practice.

Seeking to establish its parameters, artistic research can be defined as research undertaken within the realm of artistic practice or as part of an artistic project. Alternatively, it may encompass artistic endeavors employing methodologies and tools characteristic of both academic and non-academic research (Cramer, 2021).

There exists a notable expectation within the scientific community regarding artistic research, whereby it is anticipated to employ practical engagement to engender novel knowledge through the formulation of concepts, processes, and artifacts, often disseminated through exhibition strategies. The encounter with artworks is thus envisioned to elucidate not only the distinctive attributes of artistic contributions but also the attendant social, formal, ethical, and political quandaries they engender.

The conceptualization of science as synonymous with research finds its roots in Adorno’s assertion that science embodies the essence of research, while philosophy is characterized by interpretation (Adorno, 1977). Concurrently, the notion of science conceived as laboratory experimentation aligns with the essence of art itself (Osborne, 2021: 5). Amidst this backdrop, inquiries are burgeoning regarding the significance of artistic practice within academic research and the transplantation of a research paradigm from the humanities to the domain of artistic creation (ibid.).

Osborne contemplates the challenges faced by artists navigating the prescribed dogmas of research, particularly in light of the dual coding of research—a broader conception rooted in the historical interplay between art and research dating back to the Renaissance, and a narrower interpretation arising from the academic-formative context wherein art undergoes transformation through processes that legitimize it as research, thereby institutionalizing it (Osborne, 2021: 6). Central to the discourse is the contention surrounding research’s instrumental appropriation of artistic context and techniques, wherein knowledge and technologies are progressively assimilated into artistic practice (Osborne, 2021: 7). These prompts questioning regarding the feasibility of generating genuinely meaningful contemporary artwork within the confines of institutionally regulated production structures shaped by academic research.

Moreover, Osborne probes the potential for integrating arts practices into modern higher education systems as a counterpoint to the prevailing managerial and administrative paradigm of research, posing the question of whether such incorporation could serve as an anti-intellectual mechanism for effecting systemic change (Osborne, 2021: 8).

Artistic research is conventionally structured around a series of research inquiries aimed at reconstructing contextual backgrounds, methodologies employed, identifying outcomes and outputs, evaluating impacts, and disseminating findings. However, there arises a critical inquiry as to whether this framework, resembling a typical management protocol for conducting research projects, genuinely reflects the core of artistic expression, or rather represents a manifestation of a depleted notion of “research” primarily geared towards securing funding (Osborne, 2021: 9).

Numerous questions emerge when contemplating the intricate relationship between art, artistic research, and academia. The principal objective of this paper is to scrutinize, both theoretically and empirically, two distinct modes through which artistic research intersects with academic domains, with a specific focus on critically assessing the paradigmatic tensions arising from the juxtaposition of non-directed artistic exploration against the imperative for demonstrable outcomes, accountability, and process transparency inherent in managerial frameworks.

The first paragraph will attempt to get to the heart of the debate that, in recent years, has helped, since the Vienna Declaration, to revive the importance of artistic freedom in academic research. It will then introduce one of the most heated critiques, by the EARN network, of the new “arts-based research system” in order to present, then, what the group defines as a “post-research condition,” the basic premises of which it will try to illustrate. In order to investigate the way in which the sphere of the arts meets that of scientific research, particularly organizational and managerial research, a dual approach will be presented in the second section: that of artistic interventions in organizations, which have placed the focus on artistic research in organizations, and that of art-based research, developed in particular, within the Venice School of Management, and thus studies in the organizational-business sphere.

Drawing upon four case reports emanating from two projects undertaken within academic contexts, this paper will first expound upon the theoretical framework underpinning artistic interventions within organizational settings, elucidating notably how the academic community has engaged with and harnessed this modality of artistic inquiry. Subsequently, the methodology of art-based research, predominantly utilizing artistic modalities to scientifically investigate phenomena, will be delineated. Furthermore, prominent theories positing academic research as constraining artistic inquiry will be addressed. Finally, a novel method will be proposed to counteract the growing institutionalization of artistic practices.

The Vienna declaration

The inaugural international policy document delineating concepts and definitions to facilitate the integration of arts research within European higher education is the Vienna Declaration (2020). Crafted collaboratively by seven European higher arts education organizations encompassing art schools, conservatoires, and film schools, alongside two accreditation bodies for art schools, the public arts sector organization Culture Action Europe, and the Society for Artistic Research (SAR), the declaration signifies a significant milestone in the establishment of a cohesive framework for arts research within academic settings.

The Vienna Declaration characterizes arts research as practice-based and practice-driven, a domain that has witnessed rapid development globally over the past two decades and represents a cornerstone of knowledge formation in higher arts education institutions (HAEIs). Acknowledging the evolving landscape of arts research, the declaration underscores the imperative for adequate funding mechanisms to support the education of future researchers via doctoral programs, ensure the provision of suitable physical and virtual infrastructures, facilitate archiving and dissemination efforts, and foster collaborations with the business sector to enhance the impact of research endeavors (Culture Action Europe, 2020).

Furthermore, the Vienna Declaration underscores that artistic research undergoes validation via peer review, encompassing a spectrum of disciplinary expertise pertinent to the work. Quality assurance measures are conducted by reputable independent international bodies, ensuring adherence to standards outlined in the European Standards and Guidelines (ESG 2015) for Quality Assurance in the European Higher Education Area. Implicit within the declaration is a concerted effort towards institutionalizing artistic research within European art schools, with a fundamental linkage established between artistic research and doctoral programs. However, this institutionalization also implies a transformation of artistic research into a top-down practice, wherein projects, topics, and research inquiries are predetermined by academic institutions. Consequently, artistic endeavors become subsumed under predefined frameworks, project structures, and submission protocols, constraining the autonomy of artists and rendering art subservient to research objectives (Cramer, 2021).

Moreover, the declaration suggests that participation in research projects becomes increasingly obligatory, as artists may perceive these programs as one of the few remaining avenues for compensated artistic practice. In this context, the institutionalization of artistic research is portrayed as a means of affording artists institutional protection by providing opportunities for research engagement with public funding.

The Vienna Declaration characterizes artistic research as “still a relatively young field,” inadvertently disregarding its extensive history as a self-initiated and self-organized practice among artists. Indeed, research as artistic practice has thrived for over 60 years, and arguably, has roots spanning centuries if not millennia (ibid.).

Academic standards and accreditation criteria typically mandate that doctoral and postdoctoral research projects be individually identifiable and gradable, posing a structural challenge to collective artistic research endeavors. Consequently, the Vienna Declaration’s adherence to established academic norms for research validation may miss an opportunity to leverage artistic research as a critical instrument for prompting a reevaluation and revision of research standards and cultures across all academic disciplines (ibid.). In light of this perspective, the question arises: does research that lacks validation through double-peer-review systems still qualify as artistic research? Furthermore, can artistic research conducted within university settings be deemed equivalent to that showcased in art fairs and galleries, thereby fostering genuine disciplinary evolution from an experimental standpoint? Alternatively, must artistic research await the development of academic theories before it attains recognition as art (Cramer, 2021)?

A post-research condition?

In recent years, a section of scholarly research on the arts seems to have begun to question what is normally traced back to the specificity of artistic language and its profound political, ethical, philosophical, and epistemological implications and, not least, its appropriateness (Armstrong and Hughes, 2021: 47). According to some, in fact, when it comes to discuss surrounding research inherently entail considerations of objectives, the validation of knowledge, and the application of scientific rationale within the realm of art. Moreover, these terminologies not only shape the methodologies and metrics of research, such as quantifying the social and economic impact of the arts within contemporary managerial evaluation frameworks, but they may even be a symptom of a rationalistic and, in some ways, even political paradigms (Beech, 2021:51). Indeed, a part of the literature disputes these different versions of ends and measures because they seem to want to limit artistic freedom and at the same time wish to measure it, requiring a conceptualization that, in their view, transcend mere artistic knowledge. They also imply the establishment of a hierarchy of values that mandates categorization and measurement of phenomena (ibid.).

The term “research” inherently prompts a quest to delineate between intellectual creation and the tangible outcomes derived from artistic practice (Armstrong and Hughes, 2021: 58). However, the question arises: who determines and regulates the autonomy of art? The focus shifts towards understanding not so much what art ought to accomplish or be capable of, but rather how art defines itself through its practical expression (ibid.). Conceived more as a revolution or an interrogation of art-making’s very essence, the PostResearch condition of art presents an opportunity for art to reclaim its inherent power, that, according to the authors, has been compromised (ibid.). In accordance with Armstrong and Hughes, in fact, too often the use of the arts and artistic practice are instrumentalized in order to achieve research output, often too closely resembling what is commonly demanded as the product of scientific rather than artistic activity.

In alignment with this ethos, the European Artistic Research Network (EARN) was established to facilitate the sharing and exchange of knowledge and experiences within the realm of artistic research. Since 2020, EARN has organized itself into thematic working groups, constituting a network comprising artists, researchers, educators, research leaders, and their affiliated institutions. Founded in 2006, the network aims to:

• Facilitate mobility, exchange, and dialogue among researchers, artists, educators, and institutions

• Develop and promote platforms for broader dissemination of artistic research

• Foster global connectivity while respecting the diversity of paradigms, models, and cultures within the field of artistic research.

In pursuit of this objective, the group convened a Post-Research Condition conference in 2021 to elucidate and disseminate their understanding of contemporary artistic research. This term encompasses various dimensions: creative practice (including experimentalism, art-making, and the exploration of sensory potential); artistic thought (characterized by indefiniteness, speculation, associative thinking, non-linearity, and disruptive perspectives); and curatorial strategies (embodying contemporary modes of political imagination, transformative spaces for encounters, reflection, and dissemination). These conceptual realms are interrelated and dynamically cohesive, forming a series of indirect triangular relationships.

Cramer (2021) contends that the term “research” itself warrants profound reevaluation, having evolved into a distorted and somewhat toxic concept. He advocates for the emancipation of the arts from this institutionalized and antiquated notion. According to Cramer, artistic research has become subsumed within the realm of peer-reviewed scholarship, necessitating validation and incorporation of data and statistics to align with public policy and contemporary corporate research and development systems (Cramer, 2021: 24).

In order to better understand the dualism between research and artistic practice, in the second part of the paper, we will present case reports that, in our view, encapsulate the intersection of these two domains and, in some way, encompass both. These examples reflect different approaches that make art an essential component of research, while simultaneously integrating scientific research—particularly in the field of management—as a key factor in fostering a new way of engaging with creative practice. We will therefore address the topic of artistic interventions in organizations and explore how art-based research can offer a fresh perspective for scientific inquiry.

Artistic and academic research: a dual approach

Artistic interventions in organisations

Since the 1970s, there have been international experiments exploring interactions between the creative and business realms. Among the most notable initiatives (Antal et al., 2017) is the pioneering work of the Artist Placement Group (APG), founded in the UK in 1970 and now known as O+I (Organisation and Imagination). APG was instrumental in removing art from traditional spaces and embedding it within industrial environments and government offices. Additionally, Xerox PARC’s Artist in Residence Program, situated at the Palo Alto Research Center in the United States, furthered the integration of artistic practice within organizations, fostering exchange, growth, and mutual development.

Other significant endeavors, such as the ARTCOM project (Artist in Residence at Technology Companies of Massachusetts) initiated by Boston Cyberarts to facilitate collaboration between artists and technology industries, and Canon’s ARTLAB, along with the Italian example of Olivetti in the 1970s, which pioneered investments in the cultural sector and supported arts within its territory, turning factories into spaces where art could contribute creativity, knowledge, and value, contributed to the emergence of a new paradigm of interaction between art and business.

It has been noted (Grzelec and Prata, 2013) that art-in-company initiatives, which gained traction around 1983, saw significant development around 2003, with a notable increase in such interventions by organizations around 2006.

Defined as “workarts” (Barry and Meisiek, 2010) or art-based initiatives (ABIs) (Schiuma, 2011), “art interventions in organizations” aim to integrate “people, products, and practices from the world of the arts into organizations” (Antal, 2014: 77).

The term “workarts” combines the elements of art, artifact, and work, inverting the traditional notion of artwork to underscore “the work that art does at work” (Barry and Meisiek, 2010: 1507). Alternatively, for Schiuma, an ABI can be understood as any managerial action employing one or more art forms to facilitate aesthetic experiences within an organization or at the interface between the organization and its external environment, while also integrating the arts as a corporate asset (Schiuma, 2011: 47). Initially, such interventions were spearheaded by artists or managers (Antal et al., 2017), but later, the academic research sector began to engage with these practices and document their findings. In 2004, the first theoretical model pertaining to arts-in-business experiences was introduced (Darsø, 2004: 41), emphasizing mutual learning between artists and host organizations through two primary dimensions: ambiguity and involvement. Ambiguity, characterized by interpretative possibilities, facilitates the transformation of perceptions and predetermined forms, generating diverse and unforeseen perspectives on reality. In contrast, involvement fosters interaction, facilitating collaboration among different corporate roles and encouraging participation within medium-sized contexts.

The interplay between ambiguity and involvement gives rise to various manifestations such as artistic metaphors (fostering creative thinking), artistic skills (manifesting in creative practice), artistic events (involving artists within the company), or artistic products (embodying art and design objects). Learning serves as the focal point around which these combinations converge, representing a central moment to which both organizations and the arts sector aspire.

Barry and Meisiek (2010): 1511–1522 provide an initial classification of the diverse relationships between the arts and organizations. This includes art collection, where corporate artworks signify organizational values and engage employees’ attention, yet may remain purely decorative unless “activated” through management’s reinterpretation of meaning. Another category is artist-led intervention, exemplified by the pioneering work of the Artist Placement Group, where artists collaborate with organizational members to explore work processes and environments, bridging the gap between artistic and economic realms and positively impacting internal organization (ivi, p. 1514).

Several experiments in this realm, such as the Airis project in Sweden, the Nyx Innovation Alliance project in Denmark, and the Disonancias project in Spain, have yielded three noteworthy positive outcomes. Firstly, the use of artistic language introduces novel forms of communication and perspectives within the organization. Secondly, engaging with art can evoke pleasure and emotional involvement. Finally, through interaction, individuals are prompted to explore new interpretations and meanings of their everyday experiences (ivi, p. 1516).

This approach aids organizational members in “breaking away from predefined categories and uncovering the potential meanings that something may evoke or enable” (ivi, p. 1516, Hatch and Yanow, 2008). Artistic experimentation encompasses practices that enable managers to instigate organizational change through experimentation with artistic processes (Barry and Meisiek, 2010: 1517).

According to Schiuma, the distinction between artistic products and artistic processes serves as the foundation for utilizing ABI as a management tool to cultivate aesthetic experiences and manipulate aesthetic properties within organizations. Indeed, the impact of ABI on organizational components is intricately tied to the ability of the arts to engage individuals in aesthetic experiential processes and/or to shape the aesthetic characteristics of organizational infrastructures. This capacity empowers organizations to manage emotional and energetic dynamics (Schiuma, 2011: 46).

He identifies three managerial forms of art-based initiatives (ABIs), which are not only conceptually distinct but also have significant practical implications, particularly in terms of objectives and organizational impact. These forms include:

1) Arts-based interventions: Typically implemented to enhance people’s skills and attitudes, foster team-building, and support individual and organizational learning (ivi, p. 48).

2) Art-based projects: Aimed at achieving people and/or organizational development with an impact on organizational value-drivers. These projects involve the collaboration of artists and facilitators within the company to produce tangible or intangible outputs (ivi, p. 49).

3) Arts-based programs: Involving multiple artists and facilitators working together to address various business objectives related to corporate strategy. These programs articulate and allocate different projects to achieve a plurality of objectives, aiming to significantly impact the organization’s capacity for value creation through the realization of diverse project outcomes (ivi, p. 50).

In practice, each type of art-based initiative (ABI) can be implemented within organizations through various means such as training, coaching, residency activities, team-building exercises, creative inquiry, events, art collection, sponsorship, integration of art and architecture, incorporation of art and design, corporate social responsibility initiatives, and the integration of arts into organizational life.

Austin and Devin (2003) emphasize the importance of comprehending the methodologies employed by artists to enhance and drive business performance. They utilize the metaphor of artistic creation to elucidate how theater performances and collaborative artistic processes serve as vital models for understanding one’s own professional endeavors. Learning about artistic processes can stimulate comprehension of creative methodologies, such as shaping and organizing materials from disarray.

Numerous studies delve into the economic value of the arts (Bianchini, 1993; Brooks and Kushner, 2001; Florida, 2004; Myerscough, 1988; Radich, 1992). These investigations analyze the rationale and mechanisms behind the partnership between business and the arts, primarily focusing on the significance of the creative industry as a catalyst for wealth generation. They delineate two principal categories of benefits associated with integrating the arts into business: direct and indirect economic effects.

Direct benefits stem from economic activities centered around the arts, where the arts are perceived as a resource for cultural industries that generate employment and income. On the other hand, indirect economic benefits are linked to the arts’ capacity to create an environment conducive to economic development, talent attraction, and fostering creativity among individuals and businesses (Florida, 2004). The role of the arts is acknowledged as a catalyst capable of generating socio-cultural effects that can spur economic growth and benefits.

The application of an economics-based perspective seeks to quantify the value of the arts in business in monetary terms. This approach often centers on the price individuals are willing to pay to purchase or experience a work of art, as well as the economic returns associated with investing in the cultural industry. Money serves as a universal unit for communicating economic value. However, the benefits accruing to businesses from utilizing the arts for organizational change and problem-solving cannot be easily quantified in economic terms.

The integration of arts into organizational practices constitutes a realm of knowledge that inspires management innovation and fosters organizational development (Adler, 2006; Adler, 2010; Austin and Devin, 2003; Darsø, 2004).

According to Schiuma (2011): 89, the integration of art forms into management practices can drive the enhancement of management mindsets and facilitate the evolution of traditional modern management systems by incorporating new approaches and techniques that prioritize the human-based nature of organizational models and activities.

Consequently, the use of art forms in management can indeed impact bottom-line results. However, it is crucial to recognize that this impact arises from a complex web of interdependent links between the development of organizational assets and the improvement of organizational processes.

At its core, understanding the value of art for business hinges on grasping how the management of organizational and aesthetic experiences can translate into enhanced business performance.

The recognition of the organizational benefits of art-based initiatives (ABIs) is grounded in the prevailing belief within the arts domain that the value of an art form is intrinsically tied to its aesthetics (Klamer, 1996). Thus, the positive impact of ABIs on value creation stems from the aesthetic potency that the utilization of art forms can exert in relation to business aspects.

The majority of projects tested, documented, and studied thus far have been primarily initiated by universities, research centers, or facilitated within European initiatives. In all instances, intermediaries, acting as “facilitators” bridging the artistic and business spheres, have been utilized. Key organizations facilitating art-in-business projects include TILLT in Sweden, Artists in Lab in Switzerland, and Arts and Business in the United Kingdom. Since 2008, projects involving multiple countries have begun to emerge, facilitated by the allocation of European funds (such as Creative Clash, for example).

An inherent aspect addressed in nearly all academic studies on this subject is the necessity to provide tangible results: What benefits do these interventions bring to organizational studies? What advantages do they offer companies? And, perhaps most importantly, why should companies host artists (and why should artists participate in residencies within companies)?

The outcomes of these interventions have been extensively analyzed and documented, with numerous studies systematically collecting data on the subject (Cacciatore and Panozzo, 2021; Sköldberg et al., 2015; Raviola and Zackariasson, 2018). Overall, the findings mostly highlight positive aspects for both parties involved, with few exceptions noted for incomplete cases.

Indeed, in the pursuit of “bringing home results,” researchers engaged in collaborations with artists, entrepreneurs, and company employees have meticulously scrutinized every aspect of these interactions, employing methods such as data collection, interviews, and observation to measure the effects and spillover effects of various interventions. However, upon examining the outcomes and reflecting on the interventions implemented and studied, it becomes apparent that the principle of “the end justifies the means” holds true if companies achieve tangible results and artists are afforded the freedom to create their works of art. Nonetheless, this ideal scenario is not always realized, as evidenced by previous studies (Cacciatore and Panozzo, 2021).

Contrary to the claims of that part of the literature that challenges artistic research in academia as merely a tool aimed at achieving measurable results and consequent funding, much of the discourse on Artistic Interventions proves that it is possible to do artistic and scientific research without distorting the beauty and depth of artistic practice. Below, we present two case reports in which artistic endeavors were enriched through interaction with companies. These cases are part of the research project “Artificare” (2017), which emerged from the collaboration between Ca’ Foscari and Iuav Universities in Venice, aimed at investigating the origin, progression, and potential ramifications of incorporating artists and their methodologies into small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) in the Veneto region.

The two cases were chosen because they reflect the application of art-based interventions in companies as defined by Schiuma (2011) and, in addition, they directly have the university as a participant in the research. In our view, they reflect the role of scientific research in management in relation to pure art research.

Case report n. 1: De Castelli and Andreco

De Castelli Srl, founded by Albino Celato in 2003, embodies a legacy of centuries-old expertise inherited from a family of blacksmiths deeply rooted in the Piedmont area of Treviso. Masters in shaping iron, Celato has steered the company’s identity towards incorporating design, applying it to iron craftsmanship for both indoor and outdoor settings.

De Castelli seamlessly merges cherished handcrafting traditions with cutting-edge technology, ensuring that manual craftsmanship remains an integral part of the production process.

Artist Andreco, hailing from Rome and currently working between Bologna and New York City, operates at the intersection of art and science. Holding a PhD in environmental engineering with a specialization in sustainability, Andreco has conducted research on green technologies for urban sustainability. His artistic pursuits center on exploring the relationship between humans and nature, as well as the interaction between built environments and natural landscapes. Since 2000, Andreco has delved into various topics including anatomy, environmental sustainability, urbanism, ecology, and symbolism, leveraging his research findings to create new symbols.

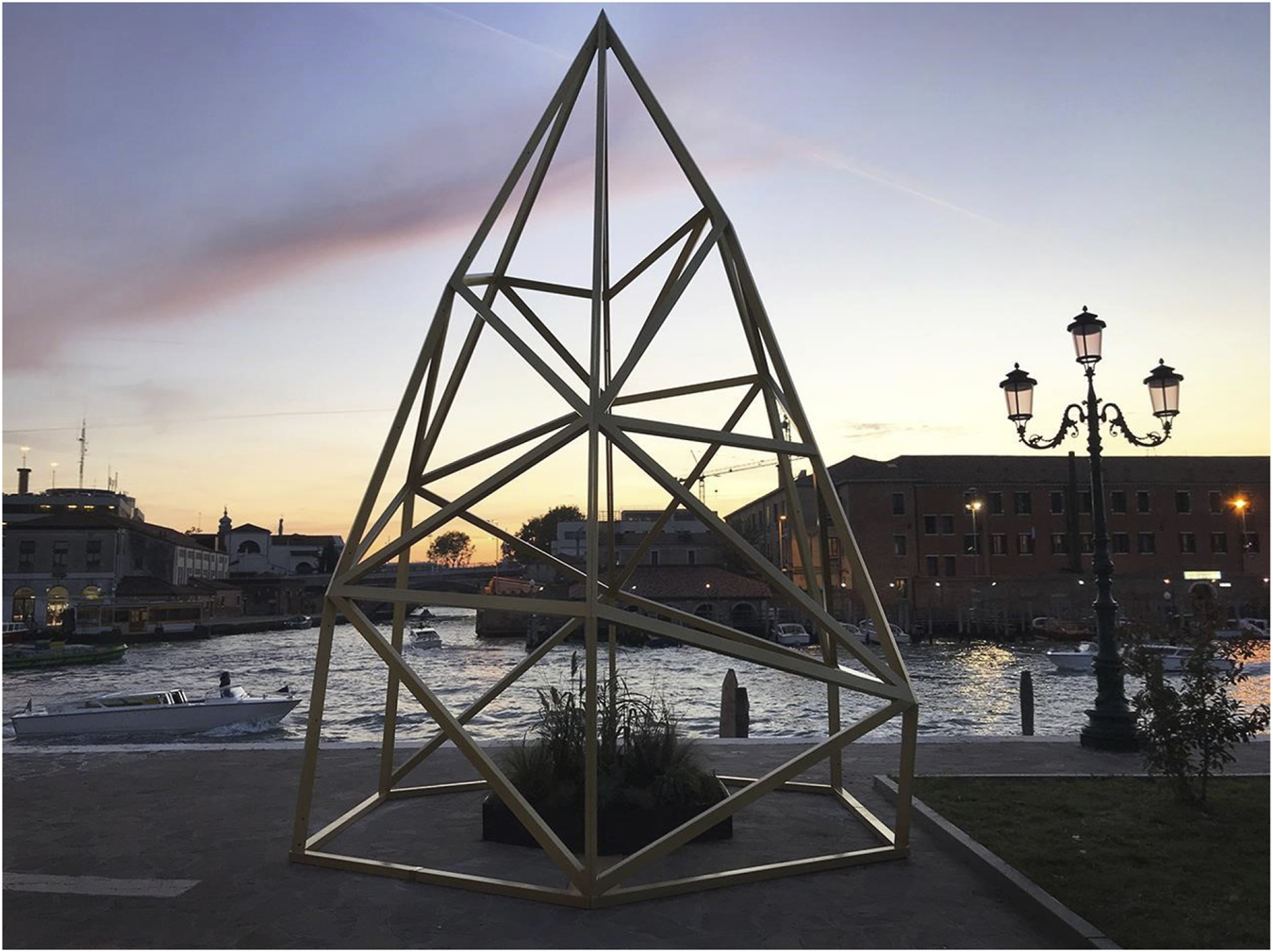

The sculpture produced in collaboration with De Castelli (Figure 1) forms part of a multifaceted project inspired by studies conducted by international research groups and organizations, as well as articles published by researchers from ISMAR-CNR, focusing on the implications of rising sea levels in the Venice lagoon. This project encompasses four interventions conceived and designed for the city of Venice: a workshop, a wall painting, a seminar on climate change incorporating artistic and scientific perspectives, and the installation itself.

FIGURE 1

Andreco. Climate 04- Sea rise, 2017. Credits: Like Agency.

The painted line adorning the wall of the Climate 04- Sea Rise artwork was initially intended to endure for 3 months along the Grand Canal in Fondamenta Santa Lucia. However, it ultimately remained in Venice, serving as a permanent fixture representing the studies on average sea levels and extreme waves, aligning with the assessments provided by the research centers involved in the project.

Furthermore, the sculpture installation accompanying the artwork will spotlight another aspect of the lagoon ecosystem (Figure 2). This installation will feature native plants, emphasizing the environmental advantages of coastal vegetation and their crucial role in climate change adaptation and mitigation, as well as in preserving the unique ecosystem of Venice.1

FIGURE 2

Andreco. Climate 04- Sea rise, 2017. Credits: Like Agency.

The artist and the company have established a shared language, embarking on a quest for innovative forms and pioneering technical and technological solutions. This collaboration evokes a sense of professionalism, extending beyond the realms of technical and scientific expertise to encompass artistic intrigue and significant cultural and social themes. Intensive production efforts spanning several months culminated in the creation of the sculpture within a remarkably short timeframe. However, the installation process encountered delays due to bureaucratic procedures among the various authorities in Venice, necessitating multiple revisions to the initial plans. Despite these challenges, individuals within public institutions demonstrated enthusiasm for the project, investing their time and expertise to ensure its realization.

The installation serves as just the initial phase, with plans for further exhibitions not only in Venice but also in other locations in the future, marking the beginning of a broader journey.

Case report n. 2: OMP engineering and Michele Spanghero

Established in 1959, OMP Engineering stands as one of Italy and Europe’s foremost providers of Life Support Systems. Specializing in self-contained, integrated, and portable life support systems, OMP caters to a diverse clientele including armed forces, civil defense and protection agencies, disaster relief organizations, civil engineering and construction firms. Their products are highly sought-after for use in camps, field operations, infrastructure development projects, and various emergency response scenarios.

Michele Spanghero’s artistic endeavors span across music, sound art, and photographic research. With a robust portfolio, Spanghero has showcased his works in prestigious national and international exhibitions. His contributions to the arts have garnered notable recognition, including being named “Best Young Italian Artist for 2016” by Artribune magazine. Additionally, Spanghero has been honored with accolades such as the In Sesto International Public Art Award (2015), the Blumm Prize in Brussels (2013), and the Icona Prize at ArtVerona (2012). Born in Gorizia in 1979, he currently resides in Monfalcone.

OMP Engineering and Michele Spanghero collaborated on a project centered around Fabbrica Alta, an industrial archeology landmark emblematic of Italy’s initial industrialization. The resulting artwork, titled “High Rise,” is a site-specific sound installation situated on the first floor of Fabbrica Alta (Figure 3). Utilizing processes and materials provided by OMP Engineering, the installation features six aluminum pipes suspended from the ceiling, each matching the height of every floor of the building. These pipes form a linear perspective, extending horizontally through the space, in contrast to the verticality of Fabbrica Alta.

FIGURE 3

MicheleSpanghero_High_Rise_IMG1_web1000-ph-credit-MicheleSpanghero-624 × 416.

Embedded within each pipe is a speaker emitting sound waves synchronized with the harmonic resonance frequencies of the building. Consequently, the installation not only visually but also acoustically enhances the spatial perception of Fabbrica Alta, transforming the environment into an immersive experience for visitors.2 OMP Engineering and Michele Spanghero maintain their collaboration by working on a new project intended for future exhibition endeavors.

Main results

As evident, the participating artists, many of whom were already established in their respective fields, produced remarkable artworks utilizing the resources and expertise provided by the partnering companies. The creative process thrived within the company environment, presenting artists with challenges that they successfully overcame. As the university overseeing this research initiative, we engaged three researchers to facilitate and oversee the interaction between artists and entrepreneurs, ensuring the smooth progress of the collaboration and monitoring the outcomes.

Regarding Case report No. 1, which focuses on the collaboration between Andreco and De Castelli, the involved researcher, who played an intermediary role, provides the following insights:

“In this particular case, we encountered an artist with an engineering background, which facilitated a quick and immediate rapport between the parties. They shared a common language, a highly professional technical vernacular. The collaboration allowed for artistic freedom while also maintaining a sense of trust and assurance. Both parties felt they were in capable hands. It wasn’t merely an artist communicating in the language of art and a company solely conversing in technical terms; rather, both possessed fluency in both domains. Consequently, the collaboration progressed smoothly and efficiently. Andreco and the company both had clear visions, leading to a rapid realization of the project. The company demonstrated significant investment in terms of time and energy from the project’s outset, recognizing its potential.”

Regarding the specific artwork:

“Certainly, it was a collaborative process, but the artist had already been working on similar projects for many years. These climate-related initiatives occur annually in different locations, with the artist having previously worked on projects in Paris, Bologna, Puglia, and now Venice. Each project explores a specific aspect of the issue.

Given the artist’s interest in addressing the rising water levels in Venice, it seemed like a compelling opportunity to intervene in this context. Together, the artist and the company discussed potential approaches, leading to the proposal of creating a sculpture representing the artist’s crystals and nature. The idea was well-received, with both parties expressing enthusiasm and agreeing to move forward with the project. They engaged in dialogue to understand any constraints and ensure the feasibility of the proposed sculpture.”

Indeed, the collaboration provided the artist with the opportunity to bring to life a project he had been conceptualizing for a while. By utilizing the company’s materials and leveraging the expertise of its workers, the artist was able to infuse his distinctive artistic style into the work, resulting in a unique piece that reflected his creative vision while also incorporating elements of the company’s craftsmanship. This synergy between the artist’s vision and the company’s resources and skills facilitated the realization of a work that may not have been possible otherwise.

“It’s fascinating to see how the workers were directly involved in the physical creation of the artwork. Their collaboration with the artist, Andreco, highlights a hands-on approach to the project’s realization. From the initial test assembly at the company’s premises to the final installation in Venice, the workers played an integral role in bringing Andreco’s vision to life. Their active participation throughout the process underscores a sense of collective ownership and pride in the creation of the artwork, fostering a deeper connection between the artistic endeavor and the company’s workforce.”

In the second case report, the dynamics between the artist and the company may have differed from the first case. It’s possible that the artist in this scenario experienced a different level of autonomy or involvement compared to the previous collaboration. This variation could stem from factors such as the nature of the project, the specific requirements or constraints imposed by the company, or the artist’s own approach to collaboration.

The researcher reports:

“It seems that the collaboration between Michele Spanghero and the company presented a unique challenge due to the artist’s pacifist beliefs and the nature of the company’s work in supplying life support systems for troubled territories. The artist’s initial hesitation stemmed from moral and ideological considerations, which created a dilemma regarding whether to engage in the collaboration.

However, despite these concerns, a meeting was arranged between the artist, the entrepreneur, and the company, which resulted in a positive outcome. The interaction between Spanghero and the company was characterized by mutual respect, sincerity, and even admiration. While there may have been some initial reservations, both parties were able to understand and appreciate each other’s perspectives, leading to an acceptance of the collaboration.

This highlights the complexity of artistic collaborations with companies, where ideological differences and ethical considerations may need to be navigated to find common ground and foster productive partnerships.”

It appears that in this case, the artist’s decision to collaborate with a company whose ideals do not align with his own reflects a compromise between artistic freedom and the practical realities of the collaboration. While there may have been initial concerns about ideological differences, the positive interaction with the entrepreneur and the opportunity to create a meaningful work of art outweighed these concerns for the artist.

In this case, the presence of the researcher-intermediary was crucial, as it served to bridge the gap and facilitate the creation of a dialogue between the artist, the entrepreneur, and the company as a whole. In a sense, the researcher convinced the artist to participate, a step that was by no means obvious, and this occurred before the artist’s encounter with the entrepreneur. The artist agreed to take part because their interaction with the company was framed within a broader research project—an artistic research collaboration with the university—in which the company became a medium through which the artist could create their works in a new way, using different materials and in different spaces.

The artist did not perceive their credibility or reputation to be compromised, as they viewed the collaboration with the business as an interaction aimed at artistic experimentation, a space for mutual understanding and the challenge of overcoming their respective differences.

A deep sense of empathy developed with the entrepreneur, along with an intellectual exchange that led to the development of a project. In the meantime, there was also the opportunity to use the space at Fabbrica Alta, the former Lanificio Lanerossi. The space was well-received, and the idea emerged to create an artistic project, something sitespecific for Fabbrica Alta.

The involvement of the company’s employees in the design and production process further demonstrates a collaborative effort in realizing the artwork. Their contributions not only added value to the project but also enriched the creative process.

In summary, while there may have been some initial constraints on artistic freedom due to the nature of the collaboration, the positive outcome and the artistic significance of the final work suggest that the artist was able to navigate these challenges effectively. Ultimately, the collaboration led to the creation of a compelling work of art that revitalized an old factory space and provided visitors with a unique sensory experience. Therefore, while there may have been limitations initially, the collaboration ultimately proved to be fruitful for all parties involved.

Art-based research

Following the experiences of artistic interventions in organizations, business schools, and universities have commenced integrating art-based modules into their curricula and initiating research initiatives focused on arts, design, and management.

Evidently, universities capable of implementing such interventions stand to gain significant benefits, necessitating a systematic evaluation. This assertion finds support in the activities of the Venice School of Management, particularly its MacLab initially, and subsequently, the aiku center, which have coordinated, supervised, and analyzed more than 60 interventions since2014.3

The origins of university arts-based research can be traced back to the conceptualization of art-based research (ABR), a term introduced by Elliot Eisner in 1993 with the aim of delineating an investigative approach focused on the exploration of representational potential culminating in aesthetic considerations and, ideally, resulting in artistic creation (Barone and Eisner, 2012: 1). However, the inquiry into the rationale behind arts-based research prompts consideration. The term itself denotes a research approach, thereby implying a methodology crafted to enrich human comprehension; it presupposes the application of aesthetic criteria in evaluating the anticipated outcomes, namely the research objectives. The essence of ABR lies in fostering an expressive form that fosters empathetic engagement with the subject under scrutiny, including by the audience. Nevertheless, the question arises: must one possess artistic proficiency to engage in artbased research? Arguably not; however, it is advantageous for the researcher to possess skills or, at the very least, an artistic sensibility (ivi, p. 55) to effectively tackle social research inquiries. Additionally, diversifying one’s artistic repertoire can enhance investigative endeavors (ivi, p. 169). ABR prompts probing inquiries and catalyzes critical discourse surrounding research subjects, yet it does not purport to furnish definitive interpretations or research resolutions (ivi, p. 166). It has the capacity to capture nuances that conventional outcome-oriented research methodologies may overlook; rather than supplanting other research methodologies, it supplements researchers’ toolkits, offering avenues for exploring topics and addressing research quandaries (ivi, p. 170). In one of his seminal works, “Art as Research,” Shaun McNiff introduces Art-Based Research (ABR) as the empirical utilization of artistic experimentation by the researcher as the principal modality for both the inquiry process and the dissemination of findings (McNiff, 2013: 4). ABR involves the researcher’s personal expression in various artistic forms serving as the primary mode of inquiry. While other subjects may engage in artistic expression within these studies, the distinctive aspect lies in the researcher’s creation of art (ivi, p. 109). Within the realm of artistic interventions, ABR implies a readiness to engage with new contexts and diverse stakeholders (Berthoin Antal, 2013: 172). As noted by Gerber et al. (2020), there exist various intersections between arts and research (Archibald and Gerber, 2018; Cole and Knowles, 2008; Wang et al., 2017). The term “arts-related research” describes instances where the arts play a peripheral role in research, serving to underscore or illustrate specific aspects of participants’ data or findings. On the other hand, “arts-informed research” entails the central use of the arts within a qualitative research framework, where the arts influence but do not form the basis of the research (Cole and Knowles, 2008, p. 59). Here, artistic data are produced by participants or co-researchers to shed light on existing qualitative data (Gerber et al., 2020). In contrast, ABR prioritizes arts epistemology and methodology, involving the systematic utilization of the artistic process as the primary means of understanding and examining experience (McNiff, 2008, p. 29). In ABR, the researcher actively employs the experience of artistic practice to investigate all stages of research, including data generation, analysis, interpretation, and representation (Barone and Eisner, 2012; Leavy, 2015; McNiff, 2008).

It has been underscored that the arts possess a distinctive capacity to generate and convey meaningful content based on the processes preceding the creation of the artwork (Refsum, 2002). Subsequent considerations pertain to the domain of the humanities. If the arts aspire to serve as a foundation for research, they must establish their theoretical framework on the pre-artistic processes leading to the creation of the artwork (ibid.), namely, the processes culminating in the construction of the artwork itself (ivi, p. 7). Moreover, ABR theory prompts reflection: does knowledge originate from the artwork or from the observer’s mind (Sullivan, 2006: 27)? Additionally, from a critical perspective, there exists a prevailing tendency to view the arts, within the practice of art-based research, as instrumental and functional to research endeavors, thereby relegating them to a form of “service” offered within the realm of education. In this context, art-based research may diminish the inherent critical and creative capacities of the arts (ivi, p. 33), particularly if the arts are employed to explore a given research topic along a trajectory developed and delineated by others.

The third case report presented below reflects what Schiuma refers to as art-based projects within companies and once again has our university of organizational and management studies as a participant.

Finally, the fourth case study is presented as an exception to the rule, as it represents a failure in relation to the concept of artistic freedom and research, in contrast to what has been illustrated so far.

Case report n. 3: D20Art Lab in Hephaestus

As part of the Horizon Europe Project HEPHÆSTUS4 (Heritage in EuroPe: new tecHnologies in crAft for prEServing and innovaTing fUtureS) the art collective D20 Art Lab5 was commissioned to carry out art-based research.

Specifically, artists were assigned the task of artistically exploring four craft ecosystems (Dals Langed, Bornholm, Venice, and Bassano del Grappa). During the kick-off meeting, the exhibition “Atmospheres of Craft” was inaugurated in Bassano del Grappa, where the artists presented their reflections stemming from an initial journey to the locations that will be the focus of scientific research conducted by the participating universities over the next 4 years (Figure 4).

FIGURE 4

A frame from “Atmospheres of Craft.” Credits: D20 Art Lab, 2023.

Regarding the boundary between artistic and academic research, Sergio Marchesini (from D20 Art Lab) elucidates in an interview:

“There is also a methodological aspect. Those coming from a research background have to map out and clearly define arguments, whereas in our way of perceiving the world, mapping is not feasible, nor do we attempt it, do we? In a sense, our artistic rationale leans more towards sampling; it originates from the notion that I will encounter a fragment of reality that somehow encapsulates the entire context in which it emerged – and so my interest lies in discovering that fragment. Because when I present it to you, you somehow perceive the entirety of that world which cannot be mapped or comprehensively collected due to its complexity. We appreciate the absence of that rigid structure; that’s the main, distinct difference for us, compared to research in the strictest sense. We could spend an afternoon searching for that particular fragment, and if we found it, we would feel as though we had discovered the world.”

And continues:

“Because sometimes, certain fragments hold significance for us. So, there is also an assumption, if you will, that such a phenomenon exists, and that this principle holds true—that it is not demonstrable, but somewhere within these fragments lies everything. As artists, we somewhat recognize them, so there is also, if you will, an assumption on the part of the artist.

This creates a distinction from the academic world, including the humanities, where one must, to some extent, substantiate their work. In contrast, artistic research truly resides in the realm of serendipity. This is also because many aspects often defy verbalization; the moment you attempt to articulate them, they elude you, slipping away. If everything could be articulated, there would be no art forms such as music or painting.”

Raffaella Rivi further elaborates:

“I am curious to comprehend the implications when another individual, engaged in research, must somehow integrate what perhaps our work, our artistic endeavors, has prompted them to contemplate. Consequently, they must articulate something that is more challenging for us to verbalize. For us, transitioning to writing a scholarly paper would be a significant leap because we believe that if we were to commence writing, we wouldn’t… We lack the language necessary to present a more logical, more utilitarian argument. We would likely confront the issue of form, and at that juncture, we would no longer approach it from an artistic standpoint. In other words, crafting a paper is not akin to composing a poem or a song; it constitutes a distinct form of expression. The chosen form inevitably shapes what can be articulated or understood. It presents an intriguing challenge for us as well, to rationalize something that inherently defies rationality.”

The artists characterize their research as a synesthetic process, wherein they capture representative facets of a broader reality—be it natural or social—that encompasses our existence. They perceive theoretical production as constraining, despite its intriguing nature. The innovative aspect of the approach adopted in the Hephaestus project lies in the detachment between artistic and academic research.

The artists from D20 Art Labs embark on artistic and unrestricted investigations into the realm of craftsmanship, drawing inspiration from various forms to convey facets of it through their artistic creations.

Simultaneously, the researchers within the project team, including ourselves, explore the same reality through a parallel trajectory. Notably, artistic research is not directly conducted by the researchers themselves, as is typical in traditional art-based research. Instead, it is entrusted to accomplished artists within the field who are afforded complete autonomy to express what they deem significant about craftsmanship. The sole constraint imposed upon them may be the research’s thematic focus: craftsmanship, and the designated locations for exploration (Sweden, Denmark, and Italy).

Case report n. 4: Delineo design and Francesco Mattuzzi

The design team at Delineo Design is committed to continuous innovation, tailoring its approach to the specific needs of each industry in which its clients operate. This mindset has established the studio as a leader in industrial design and communication, with the ability to compete in the international market. As a design “atelier,” Delineo Design excels in client relations and recognizes the global role of design management within a company, serving as a symbol of reliability and technical excellence. The studio is capable of managing projects from concept to completion.

Francesco Mattuzzi is a documentary filmmaker who uses video as a tool for research and to portray contemporary social realities, with a particular focus on subcultures and the contexts in which they emerge. In 2015, together with Alice Bolognini, he founded Plank Films, an independent production company dedicated to exploring new themes, languages, and innovations in creative documentary filmmaking, often highlighting lesser known subjects and events that are frequently overlooked by mainstream media. During his collaboration with Delineo Design, Mattuzzi created the artwork *Here-And Now*, which represents the real stimuli the body perceives from its environment through the five senses in the present moment. The video explores this concept, drawing a parallel between the designer and the athlete, emphasizing the focus and continuous training required to achieve goals by pushing beyond personal limits—an approach to confronting challenges that surpass human boundaries.

The entrepreneur had a clear expectation of the artist: to create a marketing video that creatively expressed the corporate brand to its fullest. He had enlisted a well-known mountaineer and organized helicopter shoots that lasted several weeks.

Although the artist attempted to involve the entrepreneur in all stages of the filming, keeping him informed about their progress, the entrepreneur continued to interfere in the creative process, significantly suggesting the manner and timing in which the video should take shape.

This case report exemplifies how artistic freedom can be severely challenged by overly stringent requirements tied to a specific research project or by rigid directives from the counterpart (in this case, the company), overly focused on achieving a precise result. The researcher-mediator who oversaw the interaction between the artist and the company states:

“The process was very interesting. However, the execution fell short. In the sense that the video did not meet expectations. The disappointment did not arise during the process, when there would have been a chance for recovery, so to speak… but rather at the end, as the conclusion was cut short.”

Once the filming was completed, the artist sent the entrepreneur the final edited video. At this point, the entrepreneur sharply criticized the technical aspects, expressing his negative feedback rather curtly and explicitly requesting the mediator to terminate the collaboration.

From the artist’s perspective, he faced not only interference but also aesthetic critiques that were likely unacceptable within a collaborative project aimed at exchange and mutual understanding.

The mediator continues:

“In my opinion, the company’s expectations were not fully met, leading to a sense of disappointment that was never resolved. The expectations were extremely high, and there were formal errors in the presentation. The presentation needed to be accompanied, but instead, a video was simply sent, to be clear. That should not have happened.”

As a result, the entrepreneur viewed the final video alone and interpreted it in a way that left him dissatisfied with the overall outcome.

“We are dealing with a personality who, in some way, is somewhat familiar with the world of creativity and art—the entrepreneur is also a designer. Therefore, this connection, this desire to express his own creative perspective, had a significant influence.”

The entrepreneur’s unexpected reaction, which was “very strong,” led to the project being halted, partly because the mediator was caught off guard.

What was lacking, in this case, was a gradual dialogue about what the artist was creating, namely the editing of the scenes. Overall, however, the company wanted control over the final result, the artwork, which the artist was unable to guarantee.

Furthermore, the artist’s decision to send the completed work directly may have irritated the entrepreneur, who would have preferred to be more involved in the specifics of each individual scene.

A managerial approach to the arts

In managerial studies, art-based research is often associated with the aesthetic approach within organizational contexts (Strati, 2016; Strati and Guillet de Monthoux, 2002; Linstead and Höpfl, 2000) or with the concept of creativity more broadly (Sternberg and Krauss, 2014; Moeran and Christensen, 2014). As noted by Hjorth et al. (2018): 159, there is a growing interest in organizational studies concerning creativity (Amabile, 1998; Amabile and Khaire, 2008; Florida and Goodnight, 2005; Gotsi et al., 2010; Hjorth, 2005; 2014). Art, understood as a process and a collective research practice, can positively influence organizations (Austin and Devin, 2003), organizational creativity, and leadership (Amabile and Khaire, 2008). Moreover, creativity can be seen as a social construct capable of shaping the organizational context (Koch et al., 2018) and stimulating imagination (Thompson, 2018), offering a new way of conceiving the organizational environment and the relationships within it. Art, conceived as a generative force and a set of aesthetic elements, much like entrepreneurship, creates the new and influences how we perceive things and interact with others in society (Hjorth, 2009: 220).

Furthermore, art-based research can be related to new ways of studying organizations through the creation of texts, narratives (Linstead, 2018), and videos (Biehl and Schönfeld, 2023), aimed at stimulating new awareness, sensitivity, and learning in readers. Artistic practice is also applied as a tool for experimental research (Eghenter, 2018) to identify the organizational nature of the context in which it operates within everyday life spaces. According to Scalfi, “there is always a performance underway in the organizational space. Whatever happens or does not happen in a place stem from the organizational premises of that space, whether in terms of customs, regulations, or institutional dynamics” (Eghenter, 2018: 176).

The experiences described here reflect the approach we have adopted in managing initiatives involving artists in relation to the corporate environment and especially to the corporate space. Over time, we have observed an evolution from a predominance of our role as promoters of the academic initiative, which consequently led to the selection of both the artist and the company based on a purely exploratory intent. This approach allowed for a higher degree of freedom on the artistic side and a greater willingness on the corporate side.

In this regard, our art-based projects represent a genuine progression, moving from a maximum degree of artistic and corporate freedom to a more focused and targeted level of observation. Initially, as academic promoters of the research initiative, our objective was purely exploratory, aiming to understand the phenomenon. However, over time, these studies and experiments led to a more targeted focus on specific aspects that had emerged earlier, driven by an undefined curiosity and willingness to explore.

Subsequently, we imposed stricter constraints on ourselves, which materialized in the search for and identification of a specific corporate need to which the artist could respond. The corporate need we identified, and this is what led us to increasingly collaborate with creative industries (although not exclusively), was the recognition of a phenomenon within the corporate space that the artist was asked to address. This space and the process within it interact, grounded in the belief that the corporate environment in creative industries is a space that can be innovatively narrated, and the artist’s contribution lies precisely in this narrative.

In this sense, we also distinguished the figure of the artist from that of the designer, recognizing that recent efforts have focused on aligning design with the world of creative industries to modernize and enhance the competitiveness of creative industry products through the aesthetic language of design. However, we did not focus on the product; we did not conceive of the artist as a substitute for the designer. Instead, we envisioned the artist as someone tasked with narrating a different phenomenon—one that, in our view, has been less explored or narrated in a less evolved manner, yet holds potential for further development: the corporate process, corporate identity, and corporate space. Thus, we asked the artist to intervene in these areas.

The artists we selected accepted stricter constraints, and the companies embraced a more focused presence, particularly in the realm of storytelling. A further evolution we pursued centered on the theme of storytelling itself. The companies accepted the risk of being narrated in a different way through the language of art, and the artists accepted the challenge of engaging with a space distinct from traditional artistic production—an industrial space.

It is within this challenge that perhaps a certain tension or creative opposition arises, capable of generating disruptions within the managerial dimension and opening up opportunities to innovate both corporate and artistic languages.

To address the initial questions we posed, these interventions have demonstrated that artistic involvement can enrich organizational studies by broadening the perspectives from which phenomena in the corporate context can be observed. It offers companies the opportunity to engage with a different narrative of their organizational and production processes. While artists have the chance to experiment with new materials and benefit from the resources and expertise available within companies, the companies, in turn, can adopt new ways of rethinking themselves, their products, and their internal dynamics, including those related to human and material resources.

As previously noted (Cacciatore and Panozzo, 2021: 193), the artist is tasked with responding to a need—sometimes latent—of the company: a need to communicate itself, either externally or internally. On the other side, the company’s employees are called upon to interact with the artist, engaging in an exchange that is fundamentally collaborative. This form of “organizational learning” undoubtedly represents one of the key strengths of the observed interactions.

Results and conclusion

Within the realm of social and organizational studies, artistic research manifests in two primary forms: artistic interventions within organizations and art-based research approaches. In light of the Vienna Declaration, we have delineated perspectives that diverge from institutionalist principles, which seek to standardize research output and thereby potentially restrict artistic expression itself. In a broader contemplation, we have broached the subject of artistic autonomy, particularly within a landscape where art serves as a conduit for knowledge, and academia increasingly incorporates it as a methodology for investigating issues within scientific research projects.

However, a pertinent question arises: Can art-based research yield genuine works of art, or does it merely engender “artifacts” devoid of artistic merit, serving solely as data collection instruments for academic research?

As highlighted in the case reports presented here, when an artist is included as part of an art-based interaction, any type of artistic research they conduct, even if only partial, contributes to the creation of a meaningful artwork. We are not, in fact, dealing with other types of art-based research, such as those in which researchers in the strict sense become users of artistic methods to collect useful data and creatively organize it in order to better understand and investigate phenomena.

In this regard, we presented the example of four case reports developed by our university to illustrate how artistic work can be respected and enhanced through academic research, and conversely, how it can sometimes be challenged by overly rigid parameters. Additionally, these examples demonstrate how the artist’s creative freedom can either be preserved or undermined by an obsession with measuring impact and the pursuit of scientific outcomes.

In the instances of artistic interventions involving the collaboration between artists Andreco and Michele Spanghero, the researcher assumed the role of mediator to support both the artists and the entrepreneurs throughout the collaborative process. Consequently, it was the researcher’s responsibility to gauge and document the process unfolding during the artistic residency within the company, thereby allowing the artists the freedom to explore and experiment unrestrictedly.

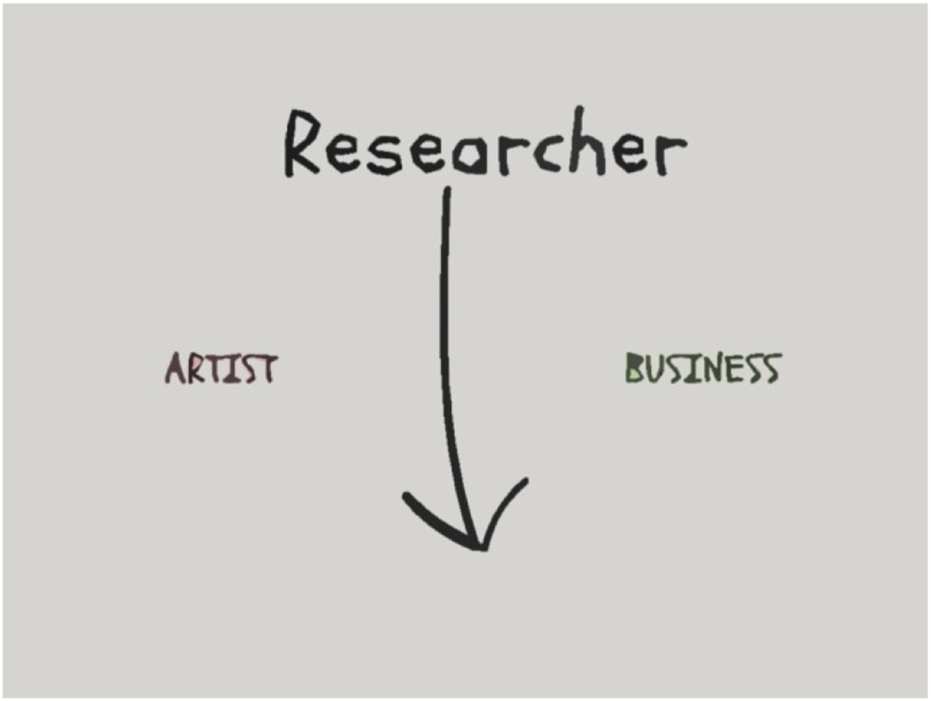

As depicted in the figure (Figure 5), the researcher’s role primarily revolves around providing assistance and support to the process of art-making, rather than actively participating in it.

FIGURE 5

The role of the researcher in our approach to artistic interventions in organizations.

In the third case, however, our role as researchers involves conducting our work concurrently with the artists from D20 Art Lab. We collect the results of their artistic research only upon completion of the artwork production.

In the fourth case, perhaps the most emblematic, the collaboration was terminated because the host company was dissatisfied with the final outcome, thus passing judgment on the artwork and deeming it inconsistent with the company’s expectations. In this sense, the company not only echoes the traditional artist-patron relationship, especially prevalent during the Renaissance, but also undermines artistic freedom, reducing it to the mere execution of a commission or corporate will.

This outcome further highlights the importance, particularly within the academic context, of establishing investigative approaches that respect the role of the artist and, even more so, enhance their vision and personal approach to artistic research. In this regard, we have referred to a “post-research condition” to emphasize the need, within the art world, to return to a state that transcends the conception of art as being “functional to something,” moving beyond traditional scientific research frameworks to reaffirm the intrinsic value of art, independent of external requirements.

Today, art is often expected to respond to scientific inquiries, solve problems at the European level, heal societal ills, or assist policymakers in directing their resources towards the right issues. However, art should not necessarily conform to political agendas or external demands; rather, it is reality, with its social phenomena, that must adapt to the impulses of the art world and the creativity of its representatives.

For all these reasons, our approach to art-based research has always been oriented toward a deep understanding of artistic sensibility, without seeking to alter the natural interactions with companies and the diverse contexts explored through various projects conducted at our university.

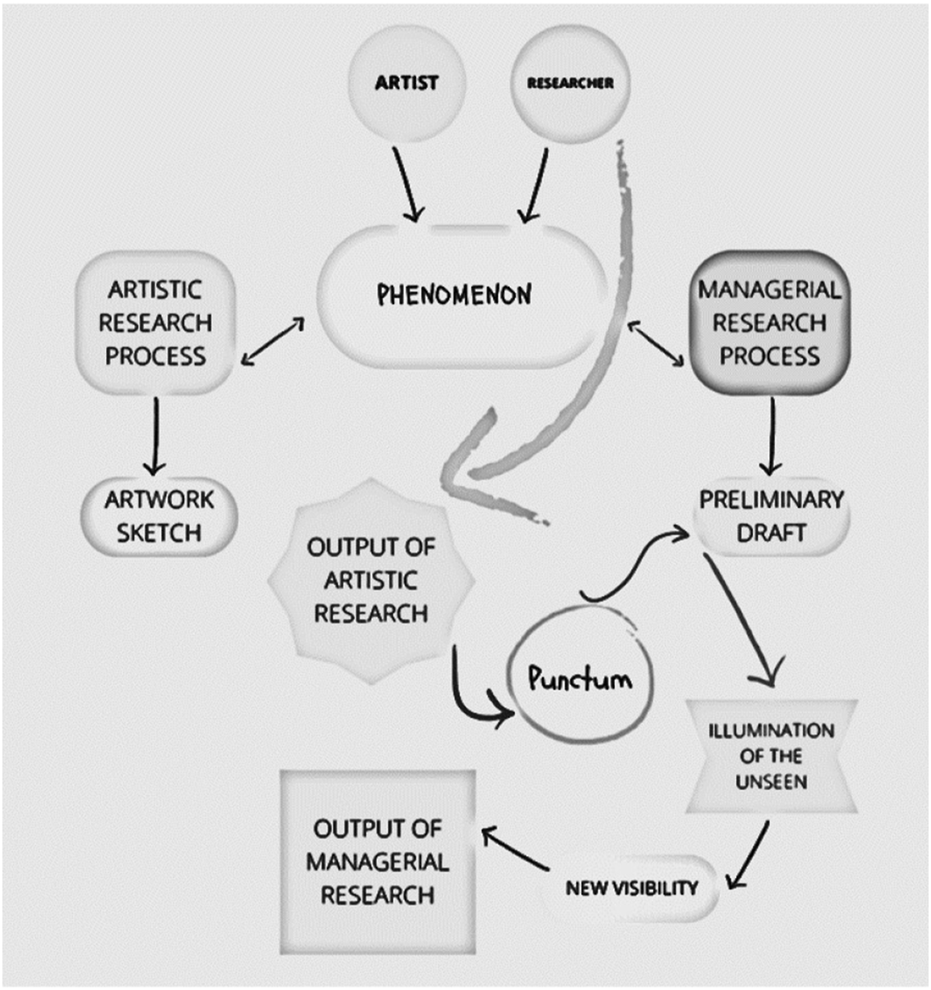

Our approach can be summarized in the following image (Figure 6).

FIGURE 6

Our art-based research method.

Referring to the mechanism of vision and the emotionality conveyed by the artistic medium, we took Roland Barthes’ aesthetics as a reference. The reason we chose to reference Barthes is due to the significance of artistic vision and perspective in the process that allows organizations to be observed, perceived, and narrated in a different way through the artist’s lens. Barthes, in “La Camera Chiara” (Barthes, 1993), delineates two fundamental components of photography: the studium and the punctum. The studium encompasses the tangible, rational, and societal aspects depicted in the photograph (such as people, objects, clothing, landscapes, streets), serving as a link between the viewer and the photographer.

Conversely, the punctum embodies a particular sign within a photograph that resonates with the viewer on a deeper, more emotional level, evoking a sense of soulful resonance or even a feeling of being emotionally wounded. Barthes struggles to explicitly define the punctum but suggests it as a sudden, incidental, and personal detail that pierces through the viewer’s consciousness, leaving a lasting impression. Importantly, not every photograph contains a punctum, and when it does exist, it is always something distinct. This concept aids in summarizing the moment when artistic research, having given birth to a work of art, elicits an emotional response, prompting the researcher to reflect and gain a renewed perspective on the object of their study. Consequently, if the outcome of artistic research is the artwork itself, it, through the punctum, offers revelatory elements to the researcher, which are further explored through action research and eventually contribute to the output of managerial research. This approach to the phenomenon operates on two parallel fronts, converging at a pivotal point representing a “turning point” for academic inquiry.

In this context, what instigates the emergence of the punctum in the researcher during the artistic process is pure experimentation, unencumbered by preconceptions or the necessity to manage and quantify outcomes. Our research method operates under the premise that the researcher’s intervention remains external to that of the artist: while artists engage in the process leading to the creation of the artwork (Refsum, 2002), the researcher observes these processes from a distance. It is only upon the realization of the artwork that the researcher enriches their theories and draws conclusions based on art. It is plausible that knowledge primarily emanates from the artwork but is further enriched by the perspective of the beholder (Sullivan, 2006), particularly if the researcher’s punctum draws from it, leading to a transformation into something else—namely, managerial research.

Hence, academic research isn’t inherently obligated to instrumentalize the arts (Osborne, 2021). This allows artists to create contemporary artworks even within an “institutionalized” framework, liberated from the constraints of impact and outcome measurement systems inherent to academic research. As we’ve observed, academic research need not develop its theories based on artistic research to define the latter as art (Cramer, 2021); rather, it’s the inverse: through artistic research, we can broaden our understanding of social reality, viewing phenomena through a different lens. Subsequently, academic and managerial research stemming from this perspective may better and more comprehensively represent the subject of our inquiries.

As observed, it is imperative for the language of art to maintain absolute freedom from the conventional management mechanisms employed to meet predetermined objectives in research projects and academic research funding frameworks.

A key realization stemming from this examination is that artistic research does not yield reproducible results and cannot be validated through conventional scientific research methods. Moreover, it may not culminate in outcomes akin to traditional results or claims of truth. Perhaps, a radical reimagining of artistic research within the academic context could involve nurturing novel modes of artistic experimentation. This approach would embrace the inherently exploratory and non-linear nature of artistic inquiry, allowing for the emergence of fresh perspectives and insights unbound by conventional research paradigms.

Statements

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

Written informed consent was obtained from the individuals for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author contributions

SC: Conceptualization, methodology, data curation, analysis, writing, review and editing. FP: Conceptualization, methodology. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. Horizon Europe Project “HEPHAESTUS” project ID 101095123 Heritage in EuroPe: new tecHnologies in crAft for prEServing and innovaTing fUtureS.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Footnotes

1.^The video of the artwork opening is available at: https://vimeo.com/318001740.

2.^The video with sound could be accessed to: https://youtu.be/7MljtssyP4k.

3.^ https://aikucafoscari.it/.

References

1

Adler N. J. (2006). The arts and leadership: now that we can do anything, what will we do?Acad. Manag. Learn. and Educ.5, 486–499. 10.5465/amle.2006.23473209

2

Adler N. J. (2010). Going beyond the dehydrated language of management: leadership insight. J. Bus. Strategy31 (4), 90–99. 10.1108/02756661011055230

3

Adorno T. W. (1977). The actuality of philosophy. Telos1977 (1977), 120–133. 10.3817/0377031120

4

Amabile T. (1998). How to kill creativity. Harv. Bus. Rev., 77–87.

5

Amabile T. M. Khaire M. (2008). Creativity and the role of the leader. Harv. Bus. Rev.86, 100–142.

6

Antal A. B. (2014). “When arts enter organizational spaces: implications for organizational learning,” in Knowledge and space. Learning organizations: extending the field. Editors MeusburgerP.Berthoin AntalA.MeusburgerP.SuarsanaL. (Dordrecht, Netherlands: Springer), 6, 177–201. 10.1007/978-94-007-7220-5_11

7

Antal A. B. Debucquet G. Frémeaux S. (2017). Meaningful work and artistic interventions in organizations: conceptual development and empirical exploration. J. Bus. Res.2017. 10.1016/j.jbusres.2017.10.015

8

Archibald M. Gerber N. (2018). Arts and mixed methods research: an innovative methodological merger. Am. Behav. Sci.62 (7), 956–977. 10.1177/0002764218772672

9

Armstrong R. Hughes R. (2021). “Embodying knowledge: on trust, recognition, preferences,” in The Postresearch condition (Utrecht: Metropolis M Books).

10

Austin R. D. Devin L. (2003). Artful Making: what managers need to know about how artists work. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Financial Times Prentice Hall.

11

Barone T. Eisner E. (2012). Arts based research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

12