Abstract

This article presents and discusses the Uniarts Helsinki Research Pavilion project, a biennial platform for developing public outreach of artistic research. Launched in 2015, the Research Pavilion has been iterated five times, three editions in the context of the Venice Biennale and two editions in Helsinki, Finland. Drawing on the experience provided by this long-term commitment to foster public outreach of artistic research, the article discusses central management and policy–related negotiations and issues that have become apparent during the Research Pavilion project. In its first part, the article presents the origin and genealogy of the Research Pavilion project, and briefly outlines the operational framing and contexts of its four first editions. The related theoretical underpinnings concerning the development of artistic research are also addressed. In its second part, the text focuses on the latest, fifth iteration of the Research Pavilion, proceeding to critically analyse its policy framework in terms of the cross-pollination as well as the pushes and pulls between academia and independent arts field, the inclusion of an artist-researcher residency programme within the Research Pavilion, and the underlying ethical issues. The article concludes by suggesting that the tensions and negotiations within the Research Pavilion project may reflect the larger context of artistic research, and it discusses possible further steps within a changing macro-political situation.

Introduction

This article reflects on the experience provided by the Uniarts Helsinki Research Pavilion (RP) project as an institutional artistic research platform experimenting with exploratory forms of making artistic research public. The article builds on the experience provided by the five editions of the biennial project that has evolved over the past 10 years. A specific focus is put on the fifth edition realised in 2023 in Helsinki. The article analyses the challenges related to establishing, developing, and managing the large-scale international project that from the very beginning has aimed at developing the public outreach of artistic research through multiple modes of operation. The next RP in 2025 will mark the 10th anniversary of the project. This article is an occasion to look back and analyse this significant and committed project of artistic research outreach.

Corpus

The reflections presented in this text build on a collection of sources related to the Research Pavilion project. These include both unpublished materials and public research discussion concerning the public outreach of artistic research. The unpublished sources consist of materials generated in and through the RP project itself, such as: 1) internal Uniarts Helsinki reports on the successive RP realisations, including numerical data on attendance, 2) feedback collected from individual and institutional collaborators, such as curators, gallery assistants, coordinators, partner universities, and artist-in-residence partners, 3) feedback collected from participating artist-researchers via feedback forms and live sessions, 4) Uniarts Helsinki internal production documents, numeric data on funding, expenditure, travels, and 5) the lived experience of the authors involved in various roles in the RP project. In order to contextualise the project in a wider frame of reference, we additionally highlight some recent research discussions addressing the strategies of making artistic research public.

The Uniarts Research Pavilion—a platform for public outreach of artistic research

Uniarts Helsinki Research Pavilion is an ongoing project with biennial events. It was launched in 2015 as an experimental initiative to develop the public outreach of artistic research in practice. The Research Pavilion defines itself as an “international and cross-institutional platform for processes, discussions, and collaborations in the field of artistic research”1. The Pavilion’s core rationale is to provide a framework for both fostering artistic research culture and showcasing its processes and outcomes. It is tailored to support the processual nature of creative enquiry that is embedded in material, performative, and collaborative settings. The project combines presentational formats such as exhibition and performance with participative activities and discursive events targeted for peer communities and the general audience. In terms of established cultural points of reference, RP can be seen as a hybrid venue that borrows from both the genres of the “festival” and the “symposium,” with their associated “independent” and “institutional” modes of operation. All RP events have been open to the public with free admission and substantial publicity. Through its five iterations and nearly 10 years of history, the Research Pavilion has evolved into one of the international focal points of the lively artistic research scene in Europe, drawing together artist-researchers and a curious public from around the world.

The Research Pavilion was originally conceived to operate in the context of the Venice Biennale (Biennale Arte Venezia). The expectation was that in the proximity of the Biennale as a central hub of contemporary art and its official programme the RP would be able to claim its self-declared role as a leading public venue of artistic research in Europe. The RP was organised in the context of the Venice Biennale in its first three iterations: 2015, 2017, and 2019.

In the pandemic context in 2021, the Research Pavilion was brought to Helsinki (Finland) to the close vicinity of Uniarts Helsinki, the project’s initiator and host institution. Beyond the multifaceted effects of COVID-19, this choice was also motivated by the high costs of operating in Venice that had led the project to a nonoptimal balance of investment and gain. Furthermore, realising the RP so far away from Helsinki involved significant amount of ecologically unsustainable traveling. In the frame of RP#3 we counted more than 100 flights taken by participants from Finland. Following these considerations, the next iterations of the project, RP#4 and RP#5, were realised regionally in Helsinki and Southern Finland. This shift was accompanied by a thorough rethinking of internationalisation goals and modes of operation from sustainability point of view.

The funding structure of the project has changed over the years as well. In 2015, as the Research Pavilion was initiated, it was mainly funded by the Academy of Fine Arts (KuvA) at the Uniarts Helsinki. For the second iteration in 2017, the funding base was widened within the larger frame of Uniarts Helsinki. Additionally, the project acquired external funding from the Louise and Göran Ehrnrooth Foundation, an important funder of scientific research and cultural initiatives in Finland. This cooperation continued until 2021. For its 2023 and 2025 editions, RP received external funding from Niilo Helander Foundation (Niilo Helanderin Säätiö), another key private cultural funder in Finland. Niilo Helander Foundation’s funding has been earmarked to directly benefit the artists working in the frame of the project, as the foundation wishes to provide support for artists and cultural life in Finland, rather than to fund institutions and institutional processes. From one iteration to another, the budget of the Research Pavilion project has varied between 100,000 € and 300,000 €, with roughly half of the budget covered by the internal funding by the Uniarts, which signals a high level of commitment for a small university.

Theoretical underpinnings

As an institutional endeavour the Research Pavilion implies a conjoint involvement in the development of the international field of artistic research. As an international phenomenon seen from the Finnish perspective, artistic research had a strong European focus from the late 1990s to the early 2000s. With the spreading of artistic research and from today’s perspective this Eurocentrism tends to appear as a limitation that can be countered with other regional initiatives that recognise the complexity of uneven conditions globally. This shift of perspective marked especially the fifth edition of the project.

Continuously negotiating its representational and geopolitical status, the Research Pavilion offers a concrete site for engaging with the questions of artistic research that are perceived as central and urgent by the participants. From its very beginning the project has been committed to cultivating the multiplicity of epistemic enquiry operating through artistic practice and creation, emphasising sensorial, sensuous, material, and practical modes of knowing and knowledge (Coessens et al., 2009). RP’s search for experimental and experiential forms of making artistic research public corresponds with the contemporary theoretical discussions, where art is seen both as an epistemic and aesthetic phenomenon (see, for example, Mersch, 2015). One of the key features that art and artistic research have in common independent of their contextual differences is their intimate relation to exhibiting creative outcomes. Exhibiting implies a high degree of self-reflexivity in public presentations in terms of form and content. For example, the editors of the special issue “Making artistic research public” of RUUKKU–Studies in Artistic Research state that “Art and artistic research are not only made for the public; they are also informed by their own publicity.” (Hacklin et al., 2022). This implies that attempts of enhancing the public outreach of artistic research are accompanied by epistemo-aesthetic negotiations and that the public presentation itself constitutes the very site of that negotiation. In the Research Pavilion project this demand for self-reflexivity is likewise important for it not forward artistic research simply on a representational level.

The two first iterations of the project grew mainly out of the Fine Arts contexts and were linked to research-oriented curatorial practices in contemporary art (see, for example, O’Neill and Wilson, 2014). The third edition marked a shift towards multidisciplinary artistic research and the questions of cultivating artistic research culture across different art forms and peer institutions mainly from the European university sector.

Throughout its history, the RP project has been an institutional experiment in balancing between the arts and academia. It has grown into a series of measures, activities, and events that can be seen as “boundary work” (Borgdorff et al., 2019). In terms of management, this has meant dealing with diverse, sometimes even incompatible, ambitions, and goals related to institutional visibility, research foci, and artistic quality. Exposing artistic practice as research is a multi-faceted endeavour that involves epistemic negotiations on many levels, from strategic planning and institutional management all the way down to individual research projects. On all these levels, a project like this, in which benevolent institutions, groups, and individuals creatively look for ways of benefiting of each other, has something opportunistic about it. We will come back to this in the critical evaluation presented in Towards a critical evaluation of the research pavilion.

Esa Kirkkopelto emphasises the institutional character of artistic research (Kirkkopelto, 2015, 49–53). Insofar as artistic research involves transformative epistemic negotiation in relation to both the arts and sciences, it involves a process of instituting, an inventive relation to the framing conditions of its own activity. It carries out “critical changes in the institutional status quo” (ibid., 52). In other words, its methods, criteria, dissemination formats, and discussion forums need to be instituted, which implies a transformational learning process that both individual artist-researchers and their home institutions are part of. As a project driven and motivated by artistic research, RP likewise is an institutional learning process that incorporates elements of invention and self-criticism. An underlying tension exists, however, between the institutional character of artistic research and the subversive drive of contemporary art, perpetually engaged in the deconstruction of its own contexts. When institutionalisation correlates with academisation, artistic research runs the risk of becoming tributary of cemented structures stemming from centuries-old academic traditions as well as rigid epistemic standpoints, provoking calls for “reclaiming artistic research” by artists from the academy (Cotter, 2019), and the neoliberal agenda of knowledge production (Manning and Massoumi, 2014). Thus, artistic research constitutes a space of continuous negotiations between the subversive push of contemporary art and the institutional space of regulations and procedures. In accordance, the Research Pavilion stands out as a context of reification of the debate around art and institutional critique.

In addition to a transformative and self-critical practice as described above, another important area in which artistic research has established new practices relates to publishing. Michael Schwab developed the idea of “exposing” practice as research in the context of online rich-media publishing and to denote the “aesthetico-epistemic transpositions of practice aimed at articulating artistic research” (Schwab, 2019, 32). Expositionality holds kinship with RP’s pursuit of carving out spaces where artistic research could simultaneously unfold in its aesthetic-expressive as well as epistemic-discursive dimensions. The presentations of artistic research aim at simultaneously presenting and epistemically reflecting their contents. The Research Catalogue, a multimedial publication platform, was developed to enable such presentation in artistic research publishing. It was used for the dissemination of RP#3 activities as well as for publishing some of the project’s results2.

While RP’s concept of an itinerant and temporary context for making artistic research public might appear rather unique, related university agencies within the artistic field can be found. For example, the “Accelerator” is a gallery space within Stockholm University’s campus, offering art exhibitions and discursive events3. Another example in the Nordic/Finnish regional context is the Aalto University’s artist-in-residency programme, dedicated to creating a “new kind of cooperation model within the university and to increase collaboration between art, science, technology and business”4. Epistemic negotiations are prevalent in the search for new forms of publicity and display in the contemporary art field as well, although often without direct reference to the notion of artistic research (See, for example, Bishop, 2023). What Tom Holert has called the “knowledgefication” (Holert, 2020, 8) of art finds a fecund ground in various artists-led initiatives and art spaces, such as Publics5 and Museum of Impossible Forms6, just to mention some examples from the Helsinki contemporary art scene.

The Research Pavilion genealogy

The Research Pavilion is founded on a societally engaging gesture on behalf of an arts university, with the ambition to extend the university’s frame of action towards and collaborate with the heterogeneous settings of the contemporary art world–first at the international hotspot of Venice Biennale, and then within the local and regional Finnish-Nordic contemporary arts context. As such, RP has been organised as a “pop-up” venue, physically outside the university’s premises, in rented, culturally, and aesthetically attractive locations. The principle of “reinventing itself at every iteration” is deeply rooted in the RP project’s experimental ethos. Thus, since its start, RP’s main responsible persons and organisational structure have changed virtually every time to reflect each iteration’s thematic and structural reformulations. The following paragraphs shortly introduce each Pavilion, with a more detailed focus on the latest – the fifth – Research Pavilion.

Curated by Jan Kaila and Henk Slager, the first Research Pavilion (RP#1) was organised in June 2015 in the context of the 56th Venice Biennale, as an exhibition with the theme of “experimentality.” The idea was to create a venue for displaying artistic research in close proximity of an important contemporary art event. The Pavilion took place in Sala del Camino – a former dormitory of an old monastery on Giudecca Island, slightly off from the Venice central area and the biennale’s busy districts. The RP#1, produced and funded by KuvA, involved institutional collaborators from the European Artistic Research Network (EARN) such as the Valand Academy (University of Gothenburg), GradCAM (Graduate School of Creative Arts and Media, Dublin), MaHKU Utrecht Graduate School of Visual Art and Design, and Università IUAV di Venezia.

With the title “Utopia of Access”, the second Research Pavilion (RP#2) was framed as a critical platform to showcase how universities function as experimental laboratories within contemporary art. It was realised in the context of the 57th Venice Biennale in 2017. The RP#2, convened by Anita Seppä, hosted three international art exhibitions between May and October, featuring a parallel cross-artistic program called “Camino Events,” which included nearly 50 workshops, artistic interventions, screenings, discussions on artistic research, and research in the arts as well as performances. The RP#2 was created and hosted by Uniarts Helsinki and realized together with the Norwegian Artistic Research Programme (NARP) and the Swedish Art Universities’ collaboration Konstex in co-operation with the Academy of Fine Arts Vienna and Zurich University of the Arts.

The third Research Pavilion (RP#3) convened by Mika Elo and Henk Slager was titled Research Ecologies. This iteration of the project shifted the focus from event production to facilitation of longer processual cooperations. A series of collegial workshops took place in Helsinki during autumn 2018 and spring 2019 before the culmination of the project in Venice in summer 2019, again in conjunction with the Venice Biennale at Giudecca island’s S. del Camino. The third iteration of the project aimed at consolidating the institutional commitment of Uniarts Helsinki as the producer and owner of the research pavilion. RP#3 was also the moment of reconceptualising the project from an event aiming at visibility into a tool for the more continuous development of artistic research culture by Uniarts Helsinki and its networks. Collaboration was taken as the starting point, both on the institutional level as well as on the level of activities. The partner institutions were Aalto University, Valand Academy of Arts at the University of Gothenburg, University of Applied Arts Vienna, and Interlab Hongik University Seoul. They all responded to a call for Research Cells, collaborative units that would use RP#3 as a platform for developing their activities and new collaborations. The activities generated together with participating artist-researchers were distributed over a period of almost 2 years, with a series of seasonal meetings in Helsinki. The high season in Venice was conceived as a combination of a residency for the research cells, a continuously transforming exhibition and a platform for network activities. RP#3 used the international research database Research Catalogue as the collaborative space for documenting and archiving the activities of the Research Cells. The outcomes of RP#3 included also two peer-reviewed special issues, RUUKKU – Studies in Artistic Research, Issue 142, as well as Phenomenology and Practice journal, Vol. 177.

In the summer of 2021 the fourth Research Pavilion (RP#4), led by Mieko Kanno and Denise Ziegler, was organised in parallel with the first-ever Helsinki Biennial, and it marked a return to more traditional formats of exhibition and performative events. RP#4 Helsinki took place at the Hietsu Paviljonki at the Hietaniemi beach — a local communal and cultural building next to the city’s liveliest summer beach. Artist-researchers participating in RP#4 showcased their projects from June to August 2021, during which the Pavilion was a hub of exhibitions, concerts, performances, workshops, and discussion. An ecological point of view triggered the decision to realise RP#4 in Helsinki instead of Venice. The focus was set on forwarding local effects and to reach local publics. An attachment to the contemporary art context was meant to be maintained through a cooperation with the Helsinki Biennial. However, this cooperation remained shallow, partly owing to the fact that the Helsinki Biennial was then realised for the first time, and the organizers did not put much emphasis on cooperation.

The fifth Research Pavilion (RP#5), led by Otso Aavanranta with the support of Mika Elo and Leena Rouhiainen8, took place in spring 2023 in Helsinki and Southern Finland. It focused on the articulations between artistic research as it is embedded within its institutional framing – namely universities and their doctoral programmes – and the experimental and enquiry-led artistic practices existing in the independent arts field. The rationale for this policy stemmed from the observation of a divide between artist-researchers working within and outside of universities, affecting not only the nature of the artistic work itself, but also its economic and societal status. There was an implicit interest to reach out and support artists working in the independent field whose working conditions had been severed by the pandemic, as well as to counter the self-isolationist tendencies of academic artistic research.

This emphasis led to a collaborative scheme with the Helsinki International Artist Programme (HIAP) and the Saari Residence maintained by the Kone Foundation, two prominent and longstanding artist-in-residency programmes in Finland. These residencies are focal points of convergence for working artists from Finland and abroad, constituting well-established partners for a university reaching out towards collaborating with the independent arts field. Marked by the post-pandemic Europe in the state of war as well as the ecologically deteriorating global situation, the tagline of RP#5 was “puzzled together,” and the curatorial choices made space for feminist, Global South, decolonising, displaced, and ecological perspectives, realised via collaborative processes between universities, arts institutions, associations, foundations and artist-researchers from different horizons.

RP#5 was structured to start with a series of artist residencies and to culminate in a multifaceted on-location event at a Unesco world heritage site in Helsinki, the historical Suomenlinna island fortification in June 2023. Three different artist-residency schemes were organised: 1) an individual 3-month working residencies at HIAP, 2) a 2-week residency in a rural setting at the Saari Residence with an ecological theme, and 3) a 1-week residency for previously constituted working groups at Uniarts Helsinki’s rural course centre in Kallio-Kuninkala, Järvenpää, Southern Finland. In total, 35 artist-researchers working within 15 different artistic projects participated in the RP#5 residency programme, gathering attendance from Finland, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Denmark, France, Italy, Greece, Peru, Kenya, U.S.A., Canada, Ireland, Taiwan, Poland, and the UK.

Diverse modes of artistic research outreach were included in RP#5. The programme involved 14 events altogether, including two exhibitions, a week of live performance events, a discursive programme with workshops and seminars, preparatory course work with Uniarts Helsinki students, a podcast series, and a public communication scheme in the city of Helsinki. All events were free of charge and open to the general public, and the total attendance of the events reached approximately 2000 persons. Figure 1 depicts three instances of the Research Pavilion, RP#3 in Venice, Giudecca Island, RP#4 in Hietsun Paviljonki, Helsinki, and RP#5 on Suomenlinna Island, Helsinki.

FIGURE 1

Three materialisations of the Research Pavilion. 1) Venice (Giudecca) Sala del Camino (photo Petri Summanen); 2) Helsinki Hietsun Paviljonki (photo Petri Summanen); 3) Helsinki Suomenlinna Island, Augusta Gallery - Helsinki International Artist Programme (HIAP) (photo Otso Aavanranta).

Towards a critical evaluation of the Research Pavilion

This section draws together three lines of analysis from the Research Pavilion project regarding cultural production and management, discussing the outcomes of RP’s public outreach strategies, RP#5’s artist-researcher-in-residency programme as well as underlying ethical issues.

Public outreach of artistic research – motivations and challenges

As described above, the key rationale of the RP project is to promote artistic research to public attention on its own terms, that is, in ways that encompass the processual and trans-epistemic nature of artistic enquiry. A taken point of departure has been the recognition that standard academic formats, such as the conference or the symposium, do not alone generate affordances for the holistic, experiential, sensorial, and conceptual characteristics of artistic research. At the same time, established art venues and their formats, such as the exhibition or performance might not as such sufficiently bring to view the epistemic dimensions and processes of artistic research. After all, one dimension of artistic research relates to the generation of new and impactful knowledge, often across given boundaries, including those between the arts and academia. Beyond the question of appropriate venues and formats, artistic research is facing the challenge of developing its own audience. As noted by Claire Bishop, the art audience in the post-internet era is less reluctant than in the early 1990s “to take up the baton of co-researcher” (Bishop, 2023). The information overload of our everyday lives has led to a situation where display strategies building on abundance of information and open structures familiar from research-based art from the 1970s onwards feel increasingly unwelcome. The effort of observing and experiencing art seems to need increasingly the support of authorial pointers. The artist-researcher is, however, not quite the same kind of author as a publicly celebrated artist. This further complicates the question of public outreach of artistic research in the era of information fatigue. As a consequence, RP needs to be seen as an instrument shaped by its task, a platform where modes of making artistic research public are critically explored and experimented with in a dialogue with peers and an emerging wider audience.

One may trace an ensemble of motivations at the background of the RP initiative stemming both from the artist-researchers themselves and from the hosting institution. This somewhat discordant ensemble of motivations revolves around public outreach as something desirable and worth developing both in terms of situational sensitivity and volume. As is the case in the society in general, here as well, a shared understanding of the goals does not mean agreement concerning the means.

For artist-researchers, making their work public is a fundamental gesture of being in the world - carving oneself into the tissue of the world and simultaneously establishing a career in the wider arts sector. For people identifying themselves as artist-researchers, there has been – and currently is – a quest for distinct spaces and contexts to showcase their work in appropriate terms, bringing forth both the epistemic and aesthetic qualities of their research. In parallel, to expose one’s artistic work as research is to declare that one has something to communicate that has relevance and epistemic implications beyond the art contexts, a contribution to society that would open up new modes of relating to the world or enlarge and multiply epistemic perspectives. Also, “joining in” is to be part of a social body, a meeting point for forging and negotiating a group identity of artistic researchers. In short, for artist-researchers developing strategies for making their research public has, in the first place, impact on their own practice, both in terms of their individual career development and their sense of belonging to a community.

For a university hosting and promoting artistic research, such as Uniarts Helsinki, the motivating factors for supporting a project aiming at public outreach are somewhat different. A primary driver of university research policy is “research impact,” defined as “significant advances in understanding, method, theory and application,” as well as a “demonstrable contribution to society and the economy, of benefit to individuals, organisations and nations.”9. In Finland, universities’ core funding is provided by the state10, which, while guaranteeing academic freedom, has a steering role in forming university policies and strategies. In the current context, there is a strong ethos of return on investment regarding higher education institutions – the taxpayers money going into universities should translate into effective, possibly measurable, effects for the benefit of society (Bornmann, 2012). For artistic research, the question of impact and societal return on investment is a topical issue. The topology of this question follows the artistic and academic double bind of artistic research: some protagonists aim to anchor artistic research into the core structures of (European) research policies, such as the Frascati Manual and knowledge production rationales (for example, see: The Vienna Declaration on Artistic Research, 2020; Baumann, 2018), while others argue for artistic freedom, its inherent subversive values and non-standard modes of operation (Cramer and Terpsma, 2019). Independent of the position adopted, it is clear that artistic research does not always conform to the models and ideals of established scientific research, such as empirism and proof, truth value, qualitative research criteria, and accumulation of knowledge. However, artistic research is not alone in such non-conformity. In academia there is increased discussion around a more variegated understanding of knowledge, and the humanities and social sciences have been developing more creative arts-based methods for a few decades now (see for example, Pink, 2010).

Through the RP project, we have been witnessing how artistic research can significantly shift the university’s interest in research impact towards the artistic field. This is a terrain where the university might not be at ease, since its processes and operation models are tailored for a mission of knowledge building and education. RP is precisely an attempt, a means for transferring the research impact topic towards the artistic domain. Currently at the Uniarts Helsinki, a differentiated language and discourse for conveying research impact in and through the arts is being developed, via the University’s strategy11, as well as by a dedicated working group, attesting to the importance of societal demands from the arts institutions. Art and artistic research share multi-faceted qualities whose effects are not easy to measure. Both in the arts and in artistic research inconspicuous experiential effects often outweigh epistemic, economic, or societal forms of impact. As a hosting institution of RP project, Uniarts has needed has struggled with weighing the investment/gain -relation facing the discrepancy between the non-obvious long-term effects of the project and the more direct forms of public response. The latter is often more rewarding and reportable at the same time as it is more superficial.

Besides research impact proper, another factor motivating the university’s investment in the RP project is visibility in the “public relations” and “public image” sense. For the responsible persons of the RP, the policy of Uniarts Helsinki has conveyed a sense of importance accorded to visitor numbers, website traffic figures, and media hits. Just as the society expects a return on investment form the universities in the form of impact, Uniarts Helsinki expects a return on its investment in RP in the form of public visibility and public relations image, aimed to foster the university’s national and international status as a pioneering hub of artistic research.

The abovementioned set of motivations for making artistic research public through the Research Pavilion are met with several hinderances and challenges. The first challenge concerns the public outreach core objective: the number of people who visit the Research Pavilion or acquire knowledge about it. The initial RP strategy was to occupy a central contemporary arts context and that RP benefits from the buzz of the Venice Biennale. All three iterations of the project realised in Venice needed to balance between different ambitions and aims. The choice of location was motivated by the idea that artistic research should take place in important contexts of art and would benefit of the international visibility and prestige related to the biennale. This certainly was the case to some extent, even if the Research Pavilion with its 50–100 daily visitors managed to attract less than 5% of the biennale audience in Venice compared to the most visited official venues of the biennale. At the same time, operating in the proximity of the biennale turned out to be a distractive element for the artist-researchers themselves. The Research Pavilion participants typically divided their attention between their own projects and the biennale mostly without making any significant connections between the two.

The experiences from RP#4 and RP#5 showed that, as the location of the pavilion, Helsinki is favourable for collaborations fostered within the project. The Helsinki Biennial didn’t constitute a distractive element for the participants to the extent that the Venice Biennale did. At the same time finding synergies with the Helsinki Biennial turned out to be anything but straightforward, even if there was a mutual interest in cooperation, especially in 2023 when Josia Krysa, the curator-in-chief of the second edition of Helsinki Biennial, put a strong emphasis on collaborations in planning the biennial. It seems that the contemporary biennials on art and artistic research have separate publics that do not mix easily. Despite significant publicity measures deployed by Uniarts Helsinki involving online and in-city advertisement, the visitor numbers for RP#5 have been relatively modest, around 2000 persons for the whole string of 14 events. A further observation concerning a wider culture audience could be made: Even if the Music Centre right in downtown Helsinki hosted some of RP events, the audience numbers remained very low. It would be interesting to find out whether free-admission events create actually less commitment in the post-pandemic world where many people decide on their cultural activities on a very short notice than events with a moderate entrance fee. For its part, RP#4 took place during the pandemic where all live cultural events were practically abandoned.

Several factors contribute to the challenges of reaching out to the larger public. Artistic research, as any research that aims to make new ground in a given field, is a highly specialised field with its own codes, idioms, and negotiations, defined within its community of practice (Wenger, 1999). The fact that artistic research operates simultaneously in the conceptual, material and sensorial domains further complicates the situation: the public needs to have tools to decode the works in, and in-between, related modes of cognising. Thus, artistic research appears as a niche, a cultural form insinuating reserved access, which simply might not have a mission for larger public appeal. Within the RP#5, this setting was exemplified by the contrast between the discursive event programme with specialist-oriented small-group thematic workshops, where content primed over participation figures, and the performance programme at the central Helsinki Music Centre concert hub, where audience numbers became a central concern and measure of success. As organisers, the authors felt that the discursive programme was closer to RP’s true calling, but at the same time, larger and outward-oriented “shows” are desirable from the university outreach and public relations policy perspective.

Semantics and their contexts are also at play in how the RP is perceived and comes across to the wider public. The name “Research Pavilion” was coined for the Venice Biennale context, where art comes as given. In that setting, there was even no reason to specify that the research involved deals with art, instead the Pavilion’s name stages a contrast with the other Venetian Pavilions which would not involve “research”, thus arguing for the specificity of this initiative. Transposed to the Helsinki context, the name “Research Pavilion” becomes an enigma: what research? According to the RP#4 visitor feedback report, the name Research Pavilion actually became an alienating element, with potential visitors being unsure and at unease as to who was allowed to enter the Pavilion, and wondering if the space and events were reserved for researchers. Thus, in the Finnish context, the name has consequently been supplemented with subtitles and explanatory taglines such as “exploratory art” for public communication.

Another challenge for bringing artistic research to the public attention is its processual nature which involves experimentation, trials, and tests. Artistic enquiry typically moves between material practices and conceptual practices in an iterative manner (Bhagwati, 2005), mapping out the possibilities and potentialities of a specific socio-material arrangement (Michael, 2019). Iteration and mapping involve reflective temporal processes that are challenging to convey in traditional artistic output formats such as an exhibition or a performance. Artistic research has inherent qualities which weigh towards temporal, spatial, and multisensorial deployments, as reflected by the notion of “expositionality” (Schwab, 2019, see also Theoretical underpinnings), and by RP’s search for suitable artistic research public formats. In practice, the inherent aims of artistic research tend to produce works that are “non-spectacular” in nature, in opposition to the material-intensive and lavish settings that are often found in more mainstream contemporary art. This contrast has been very apparent in the setups informed by the proximity of the biennales of Venice and Helsinki. Large-scale biennale exhibitions and the Research Pavilion’s more modest, “traces of enquiry” -type of arrangements trigger different expectations and attract different audiences. Yet another set of push-and-pull negotiations that affect artistic research outputs is the academic – artistic binary, with university doctoral programme and funding structures infusing norms and regulations on the artistic research practices and outcomes, contrasted by the subversive and disobedient ethos that animates some lines of modern-to-contemporary art and can be quite tangibly present in higher arts education. Luckily art universities are given the prerogative to question academic conventions on artistic grounds. With their creative solutions in research in the arts and artistic research they have also acted as inspiration for other academic fields. With the forces and negotiations described above in mind, the RP project has explored a number of processual and participative settings for making artistic research public, such as artist-researcher residencies, working spaces and processes opened to the public, exhibitions with background information and discursive outputs, artist talks, discursive events, and panels discussions. The next Artist residencies within the Research Pavilion #5 - articulations, tensions and overlaps of institutional and non-institutional artistic research is dedicated to a closer analysis of one of these modes of making artistic research public experimented with in RP#5, namely, artist-researcher residencies and subsequent outputs.

The RP project’s experimental ethos can be seen to certain extent as opportunistic in the sense that the iterative transformations of the project have mainly been driven by changes in the framing conditions rather than by a sustained curatorial vision. As an instrument shaped by its task, the RP project has been a foyer for many kinds of ambitions and agendas, to the extent that one could say that its implicit task has become to remain open for reshaping whenever the circumstances require. While not fully planned, intended, nor desired, this kind of opportunism is not only something negative or something to be avoided, since it has a logic that can be modulated collegially and collectively. The iterative drift of RP has been harnessed in favour of shaping temporary free spaces where institutions, groups and individuals can come together and share ideas, practices and outcomes of artistic research.

Summing up the above discussion, the question of making artistic research public via RP appears as a complex landscape of multiple lines of tension and negotiation. The divergent agencies of artist-researchers, the University, public expectations, as well as artistic and academic policies contribute to pulling the Research Pavilion’s organisation and emphasis towards solutions that are essentially compromises between the diverging interests.

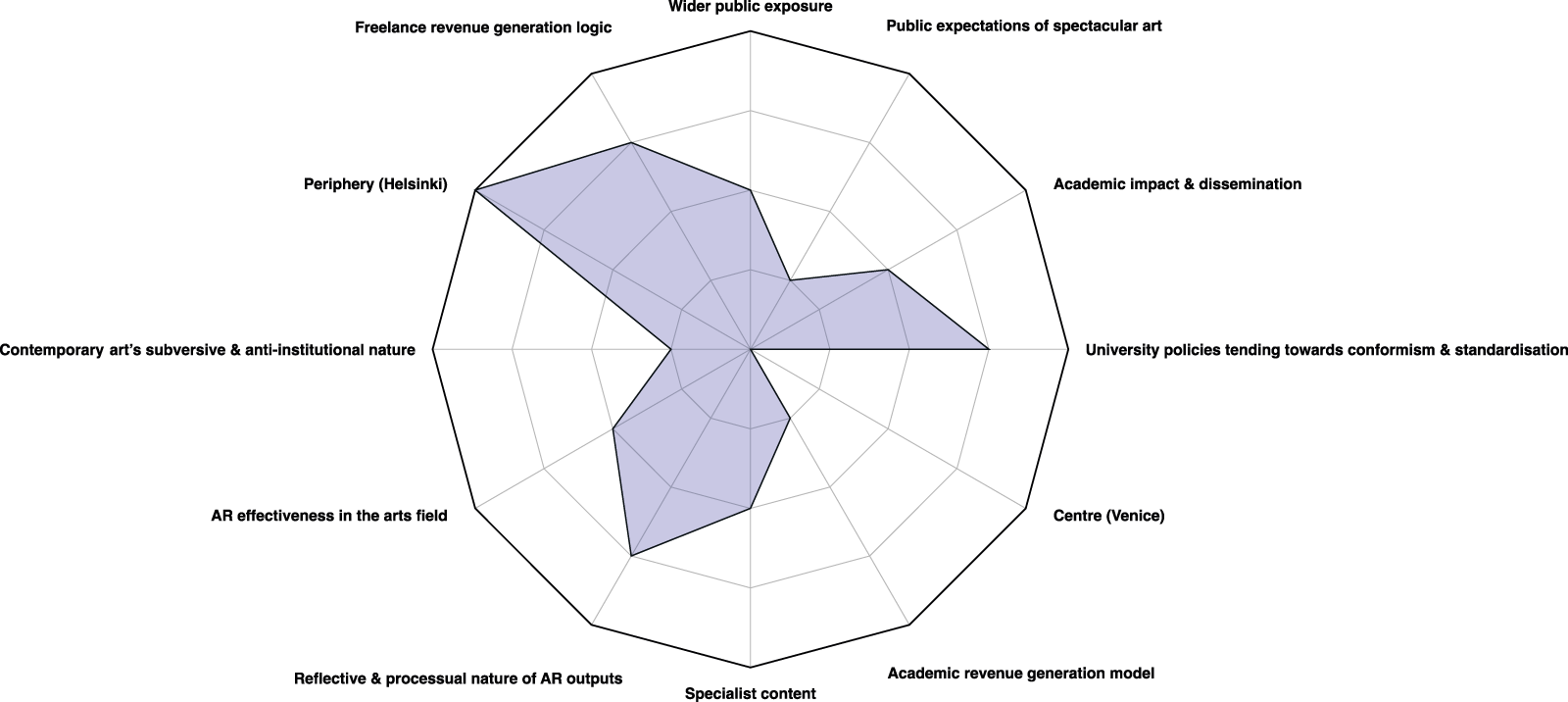

Figure 2 charts a set of lines of tension and negotiation stemming from our analysis and may serve on a more general level to depict in a compact format the divergent forces at play in making artistic research public.

FIGURE 2

Graphic presentation of lines of tension and negotiation emerging from the Research Pavilion project. A tentative weighing of different attractors has been attributed according to RP#5 evaluation conducted by the organising team in the aftermath of the project. The graph demonstrates the policy framework of RP, as a project tributary to a set of opposing cultural, educational and economic attractors, and which is compelled to make choices between them at each iteration. Note: AR in the chart refers to artistic research.

Six pairs of negotiation are presented, with opposite poles representing opposing - or at least diverging - interests, motivations and contexts that are present in the making public of artistic research. The chart is intended to be representative of some of the strategic discussions underlying the five different Research Pavilion iterations. The data leading to this graphic representation emerges from the RP core team’s project analysis based on the corpus presented in

Corpus, that is, written reports from Research Pavilion iterations 1 to 4, including feedback from artist-researcher participants, curators, collaborators, employees and partner universities. The main backdrop on which this analysis is constructed is the choice articulated in RP#5 for emphasising the artistic research emanations within freelance arts field. This choice exposed the RP project directly to the independent arts scene, and brought up a multitude of discussions and negotiations between the academic and freelance agencies. As such, RP#5 served as a catalyst, bringing underlying figures and tensions in plain sight. The chart presented below is specific to the RP context and does not pretend to any kind of exhaustiveness of the pushes and pulls within the larger artistic research scene. However, structures analogous to those presented here might be present in other contexts and projects, and may be useful in elucidating them. The six pairs of negotiation are:

− Wider public exposure <–> Specialist content

− Public expectations of spectacular art <–> Reflective and processual nature of AR outputs

− Academic impact and dissemination <–> AR effectiveness in the arts field

− University policies tending towards conformism and standardisation <–> Contemporary art’s subversive and anti-institutional nature

− Centre (Venice) <–> Periphery (Helsinki)

− Revenue generation model within University <–> Freelance revenue generation logic

Something of these tensions might be described as the divergence of exposing and imposing, since the gestures of exposing practice as research do not impose themselves on the visitor, at least not in any spectacular way. Instead, the transformative qualities of artistic research as expositional activity unfold slowly through long-term engagement with the issues addressed.

Note: the weighted plotting of these axes of tension into a chart does not imply numerical analysis, rather a pictural approach representing the strategic choices made for the fifth iteration of the Research Pavilion project.

Artist residencies within the Research Pavilion #5 - articulations, tensions and overlaps of institutional and non-institutional artistic research

As presented in The research pavilion genealogy, the fifth Research Pavilion in 2023 included a series of artist-researcher residencies, organised in collaboration with prominent residency programmes in Finland. While having been received with enthusiasm and nurturing very relevant and interesting lines of work by the artist-researchers involved, the inclusion of independent artist-researchers within RP#5 residency programme made also apparent some deep running differences in working cultures between university-embedded and independent artistic research. These differences affecting the expectations and modes of operation have been a constant source of tension and possibly irresolvable negotiation within different RP iterations.

The most evident discrepancy concerns the economic conditions between artist-researchers in salaried positions within universities and freelance artists working in a rolling economy of self-employment via short-term engagements and sales. A university dealing with independent artist-researchers-in-residency meets a set of expectations regarding workflows and working conditions that are not in its habitual playbook. In practice, this entails covering costs, fees, short-term contracts, per diems, materials, and providing access to infrastructure, which may be exotic in regard to the established types of university working contracts and demanding an important amount of administrative work that the university does not necessarily have the means to provide. In contrast to the independent artist-researcher’s situation, the institutionally engaged artist-researchers areoften entitled to longer-term working contracts with social security and heath care benefits, which fit the existing conventions within the university. The temporal dimension is entangled with the economic discrepancies. Independent artist-researchers often work with shorter time frames than the university. For example, the longest residency periods in RP#5 were 3 months – whereas a typical minimum university research engagement might be a year.

Related to the economic and temporal frames, there are also differences in the aims between independent-field artist-researchers and ones engaged in a university. Independent artist-researchers’ economic landscape is shaped by the art market with its private and institutional actors, perceived prestige levels, sales, invitations, and awards. The independent artist-researchers work with these in mind, developing individual strategies for career management. In the academic domain of artistic research, the economic landscape is mediated by academic merits, that is, academic publications and relevant artistic merits (not necessarily monetised, as would be the case with independent artist-researchers), which condition the longevity and advancement of one’s career. In this sense, it is possible to argue that the independent and academic strands of artistic research are pulled towards different socio-economic frameworks, or “art worlds” (Becker, 2023), with diverging logics of operation. However, also academic artist-researchers are in a precarious situation as there are only a very few genuine research positions on offer for them. They often rely on fixed term competitive research funds applied from research funding organisations not all of which fund artistic research.

Stemming from these differences, the conditions and objectives for creating, producing, and showing artistic research work may be substantially different. An independent artist-researcher-in-residency might be inclined to use the time and resources for producing work that is transposable to different, monetarised settings on the art field, whereas academically employed ones might spend the time in documentation and analytical reflection. Yet when the Research Pavilion is concerned as an environment if offers both artist-researchers working within the arts field or universities a time limited project-based opportunity to forward their creative undertakings.

In a stance of RP#5 self-analysis, the university-organiser brought in academically-weighted expectations regarding the artistic research processes and outputs. As a result, the internal assessment of the “independent artist-researcher-in-residency programme” was that the working periods were too short for allowing a full blossoming of lines of artistic enquiry, and that the results were too oriented towards artistic artefacts, that is, preparation of pieces and performances to be transposed to the larger art market. The university was left with little academic substance and traces of epistemic enquiry such as publications, presentations, and research expositions. In consequence, the RP#5 residency programme effectively pointed at the lingering questions of artistic research ownership and agency, making inherent tensions palpable. It would be illusory to think in terms of “solutions” or “best practices” in such a precariously balanced and complex setting, but the experiment brought up two emergent ideas to be developed further. The first concerns the prospect of re-thinking the university as a platform for diverse agencies to converge and co-operate. This would entail a radical shift in university working cultures and processes, but emblematic traces from, for example, Bauhaus (Ellert, 1972) and Black Mountain College (Molesworth and Erickson, 2015) create inspirational historical perspectives. The Research Pavilion could perfectly mend itself into such a radically experimental arena. The second prospect concerns a comparison between artist residencies and university research labs. In many ways, the current international circuits of artist residencies function as temporary spaces of exploration for artist-researchers, allowing them to concentrate on artistic exploration within a given temporal and material frame. In the university context, research labs appear to fulfil the exact same function. Thus, an emerging topic from RP#5 is to reflect upon similarities and differences, pros and cons, between these two socio-economic organisations of artist-researcher exploratory spaces, and eventually draw new models for experimenting with in ulterior RP#5 realisations.

Ethical questions on university agency within the independent arts field

The Research Pavilion project’s experiments have extended Uniarts Helsinki’s agency partly within the independent arts field, where it has encountered and adapted to non-university-like working cultures and modes of operation. In steering these encounters, the RP organisational team has been vividly aware of the ethical dimensions they entail. To start with, the university is a selective institution. When it comes to third-cycle and postdoc artist-researchers, they have been screened through many successive stages of gatekeeping. The “chosen few” who have made it to doctoral studies and beyond, and especially those who have managed to secure funding for their work and to enhance their career, are in a favourable position regarding their independent peers in terms of financial stability and institutional endorsement. A first ethical consideration for the RP has been to find ways to level the field and not pit categories of artist-researchers between each other. Such considerations have led to curatorial choices such as the RP#5 emphasis on promoting independent artist-researchers.

Furthermore, in our cooperation with the Helsinki International Artist Programme (HIAP) and Saari Residence, specific care was taken to formulate a collaborative model where the residency programmes’ established modes of operation were respected. The university may appear as a big financial player in comparison with residency programmes, imposing a specific responsibility for its actions, and our team perceived a danger of the university colonising the independent actors with its own logic and financial power. In consequence, in the RP#5 cooperation model, the residence period slots were “bought” from the residence centres by Uniarts Helsinki, without the university involving itself in the management of the residencies. This model allowed for each partner of the cooperation to retain its own logic of functioning. Collaborative gestures and moments grew out of this setting, with mutual input in organising events and gatherings.

Finally, RP#5 has brought the university to exert curatorial power in the independent arts field, involving a responsibility towards policies of inclusion and diversity. Artist-researcher-in-residency choices were screened with these policies in mind, and the discursive and live programmes of RP#5 were intentionally steered to include global, decolonial, and feminist agendas. Ethics of care were consciously maintained towards the resident artist-researchers, ensuring optimal conditions for their residency periods. However, the maintenance of this attitude of care beyond the residency period proper has proved to be difficult for Uniarts. As soon as the (short) residency periods were over, the agreements between the university and the artist-researchers reached their end, and the residents moved on to their next engagement, in other countries in most cases. With the university’s agenda rolling on and staff working hours full, it has proved difficult to maintain contact with the RP#5 residents. A longevity of contact and follow-ups on the development of the artist-researchers’ enquiries would be very desirable from the RP’s point of view, as it would be a means to remain in contact with the emerging epistemic substance that is at the core of the RP initiative.

Conclusions and policy development

In this text we have outlined the rationale and genealogy of the Uniarts Helsinki Research Pavillion project, as well as developed a set of analytical strands regarding RP’s public outreach strategies. As a central outcome, we have depicted RP as a space of negotiation between opposite pulls form different stakeholders of artistic research such as the artist-researchers themselves, the university, institutional policies, independent arts field, and art market. Following this equation, the successive RP iterations appear as compromises tailored each time to reflect topical interests of selected stakeholders, but while doing so, inevitably downplaying their possible divergencies. In consequence, the “perfect Research Pavilion” is impossible to realise.

Considering RP as a reification of the theoretical debates in and around artistic research, our critical evaluation of the Research Pavilion project speaks about the ambivalent position artistic research holds between art and academia. Not “pure art,” nor “pure research,” artistic research holds a position of fragility, instability, and hybridity between these established entities, and to which it is constantly forced to refer. Tributary of its constituent fields, artistic research is a fluid object that remains engaged in constant negotiation with the changing artistic, economical, societal and political landscapes. While the absence of consolidation may endow resilience and agile effectiveness to the field, it may also produce positions of perpetual compromise. The ebb and flow of artistic research between the frames of reference of art and academia could constitute a root cause for its apparent inefficiency in transforming its potential to tangible, world-shaping results. Steps towards the consolidation of the field into a discipline constitute steps away from the creative essence of the arts, and inversely, steps towards radical artistry dilute the epistemic research-related discourse belonging to the university, each move undermining the potential for societal effects of artistic research. The Research Pavilion project, in its successive iterations, has experimented with policies of consolidation on both sides by involving university agencies as well as independent art contexts. A possible way forward could be a more radical engagement of independent actors and contexts within the RP steering group and modes of operation, working towards a Research Pavilion that would constitute a heterogeneous platform for diverse agencies to operate on. However, the current macro-political situation with Europe at war and fencing with mounting threats to the democratic and rule-based society is changing the landscape, as effects from the macro-level trickle down to the academic and cultural sectors. Uniarts Helsinki, and within it, the Research Pavilion, are witnessing the decrease of their resources, negatively affecting the possibilities to engage with the independent arts field in and terms that would be economically compliant with the freelance working culture.

Statements

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Author contributions

All three authors have been involved in the organisation of the Research Pavilion’s successive iterations. OA acted as the director of the fifth and latest RP and has been the main writer of the text. ME and LR have both added their viewpoints and contributed to the analysis and writing. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Footnotes

1.^ https://www.uniarts.fi/en/projects/research-pavilion-project/

2.^ https://www.researchcatalogue.net/view/474888/474889

3.^ https://acceleratorsu.art/en/visit/

4.^ https://www.aalto.fi/en/research-art/artist-in-residence-programme

6.^ https://www.museumofimpossibleforms.org/

7.^ https://journals.library.ualberta.ca/pandpr/index.php/pandpr/issue/view/1951 https://www.researchcatalogue.net/view/474888/474889

8.^ https://www.uniarts.fi/en/research-pavilion/

9.^ https://www.ucd.ie/impacttoolkit/whatisimpact/

References

1

Baumann P. (2018). Dire Moby-Dick par la recherche en arts. Bordeaux: Presses universitaires de Bordeaux.

2

Becker H. S. (2023). Art worlds: updated and expanded. University of California Press.

3

Bhagwati S. (2005). The AGNI methodology. Available at: https://matralab.hexagram.ca/the-agni-methodology/the_agni_methodology.pdf.

4

Bishop C. (2023). Information overload. Available at: https://www.artforum.com/features/claire-bishop-on-the-superabundance-of-research-based-art-252571/.

5

Borgdorff H. Peters P. Pinch T. (2019). “Dialogues between artistic research and science and technology studies: an introduction,” in Dialogues between artistic research and science and technology studies. New York: Routledge.

6

Bornmann L. (2012). Science and Society: the societal impact of research. EMBO Rep.13, 673–676. 10.1038/embor.2012.99

7

Coessens K. Crispin D. Douglas A. (2009). The artistic turn: a manifesto. Leuven: Leuven University Press.

8

Cotter L. (2019). Reclaiming artistic research (Berlin: Hatje Cantz Verlag).

9

Cramer F. Terpsma N. (2019). What is wrong with the Vienna declaration on artistic Research?Open! Platform for art, culture and the public domain 21.

10

Ellert J. C. (1972). The Bauhaus and Black Mountain College. The Journal of general education24, 144–152.

11

Hacklin S. Heikkinen T. Ziegler D. (2022). Making artistic research public - editorial. Ruukku – Stud. Artistic Res.19. Available at: http://ruukku-journal.fi/fi/issues/19/editorial.

12

Holert T. (2020). Knowledge beside itself. Berlin: Sternberg Press.

13

Kirkkopelto E. (2015). in Artistic research as institutional practice. From arts College to university. Subject overview, articles, reviews, and project reports. Editor LindT. (Stockholm: Swedish Research Council), 49–53. AR Yearbook 2015.

14

Manning E. Massumi B. (2014). Thought in the act: passages in the ecology of experience. Minneapolis: Univeristy of Minnesota Press.

15

Mersch D. (2015). Epistemologies of the aesthetic. Berlin and Zurich: diaphanes.

16

Michael M. K. (2019). Repositioning artistic practices: a sociomaterial view. Stud. Continuing Educ.41 (3), 277–292. 10.1080/0158037x.2018.1473357

17

Molesworth H. A. Erickson R. (2015). Leap before you look: Black Mountain College, 1933-1957. Yale University Press.

18

O'Neill P. Wilson M. (2014). Curating research. Open Editions/De Appel.

19

Pink S. (2010). The future of sensory anthropology/the anthropology of the senses. Soc. Anthropol.18 (3), 331–333. 10.1111/j.1469-8676.2010.00119_1.x

20

Schwab M. (2019). “Expositionality,” in Artistic research charting a field in expansion. Editors de AssisP.D’ErricoL. (Washington: Rowman and Littlefield), 29–32.

21

The Vienna Declaration on Artistic Research (2020). The Vienna Declaration on artistic research. Available at: https://societyforartisticresearch.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/Vienna-Declaration-on-Artistic-Research-Final.pdf.

22

Wenger E. (1999). Communities of practice: learning, meaning and identity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Summary

Keywords

artistic research, institution, art biennale, experimentation, public outreach

Citation

Aavanranta O, Elo M and Rouhiainen L (2025) Strategies for making artistic research public: a case study of the Uniarts Helsinki Research Pavilion project. Eur. J. Cult. Manag. Polic. 14:13070. doi: 10.3389/ejcmp.2024.13070

Received

31 March 2024

Accepted

12 December 2024

Published

06 January 2025

Volume

14 - 2025

Updates

Copyright

© 2025 Aavanranta, Elo and Rouhiainen.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Otso Aavanranta, otso.aavanranta@uniarts.fi

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.