- 1Viljandi Culture Academy, Faculty of Arts and Humanities, University of Tartu, Tartu, Estonia

- 2School of Humanities, Tallinn University, Tallinn, Estonia

This article examines how an entrepreneurial mindset can act as a facilitator of knowledge management and co-creation within arts universities through the lens of Communities of Practice (CoPs). While entrepreneurial education in the arts is often framed as means to economic ends, we argue that its role extends significantly further. By integrating the entrepreneurial mindset into CoPs—where students, educators, and industry professionals collaboratively engage—arts universities can transform into dynamic learning organizations that align individual development with institutional knowledge creation. However, tensions arise within the CoPs when entrepreneurial education clashes with core artistic identities. Drawing on qualitative data from two European universities, this study critically examines the potential of entrepreneurial mindset for managing these tensions through the SECI model of knowledge management. Our findings reveal that when positioned as a tool for knowledge co-construction entrepreneurial mindset can facilitate alignment of students’ artistic values leading to both individual empowerment and institutional evolution.

Introduction

In recent years, the integration of entrepreneurial education within arts universities has become increasingly prominent, yet it remains a contentious subject. Traditionally, entrepreneurial education has been framed as a means of preparing students for economic engagement, equipping them with skills for the marketplace (Bennett, 2009; Gibb, 2002). This approach aligns with broader trends in higher education, where universities are expected to foster employability, innovation, and entrepreneurial thinking across disciplines. However, in arts education, where artistic identity and creative freedom are often prioritized over commercial concerns, entrepreneurial education introduces a tension between artistic values and economic realities (Bennett, 2008; Ellmeier, 2003).

This tension frequently results in student resistance, as entrepreneurial competencies are often perceived as being at odds with core artistic identities (Kuznetsova-Bogdanovitsh, 2022). Instead of feeling empowered, students often experience entrepreneurial education as an additional pressure that detracts from their creative practice. Despite these challenges, we propose that when critically engaged with, entrepreneurial education—specifically, the development of an entrepreneurial mindset—can play a pivotal role in facilitating personal transformation, collective learning, and knowledge co-creation in artistic and professional contexts.

This article positions the entrepreneurial mindset, defined as a proactive, idea-to-life approach, as a key facilitator of knowledge management in arts universities. We explore how this mindset, when integrated into existing Communities of Practice (CoPs), can help bridge the gap between individual learning experiences and broader knowledge dynamics. CoPs, as conceptualized by Wenger (1998), are spaces where learning occurs through shared practice and collective engagement. In arts universities, CoPs are not only integral to the development of artistic skills but also offer potential for embedding entrepreneurial education in a way that aligns with students’ artistic identities.

To frame our analysis, we draw on the SECI model (Nonaka and Takeuchi, 1995), which explains the dynamic process of knowledge sharing and management through the interplay between tacit and explicit knowledge. By examining the intersection of the SECI model, CoPs, and entrepreneurial mindset, we explore how entrepreneurial education can facilitate knowledge co-creation within arts universities, contributing to both individual student empowerment and institutional development.

While much research has been conducted on entrepreneurial education in business and STEM fields (Audretsch and Bielitski, 2020), its role in arts education remains less examined, particularly with regard to knowledge management and CoPs. This study seeks to fill that gap by investigating how entrepreneurial mindset can be strategically positioned to foster knowledge creation and sharing, not only within individual learning experiences but also as a driver of organizational learning and transformation. Through qualitative data from students, educators, and leaders in two European arts universities, we aim to shed light on how the integration of entrepreneurial education can lead to more holistic and sustainable learning ecosystems.

Our findings suggest that entrepreneurial mindset, when framed not solely as a set of economic competencies but as a tool for navigating uncertainty, building social and cultural skills and capital, and driving creative collaboration, holds transformative potential for arts students. However, this transformation requires that entrepreneurial education be aligned with students’ artistic identities and values, rather than imposed as a purely instrumental set of skills. Hence, in this article, we explore how such alignment can be achieved, how entrepreneurial mindset can act as a bridge between individual and collective knowledge, and how these processes contribute to reshaping arts universities into more dynamic learning organizations. While the findings offer a critical analysis of entrepreneurial education practices, the conclusion takes on a more actionable tone, presenting recommendations for arts universities to rethink and refine their approach to implementing entrepreneurial competencies. These recommendations aim to inspire institutions to create environments where students can thrive, balancing their artistic ambitions with professional growth.

Theoretical framework

This study operates within a multifaceted theoretical framework that interconnects entrepreneurial mindset, Communities of Practice (CoPs), and the SECI model of knowledge management. These frameworks allow us to explore how knowledge co-creation, sharing, and management function within the dynamic, practice-oriented environment of arts universities. By examining how entrepreneurial education intersects with these frameworks, we illuminate the potential for fostering not just individual growth but also the transformation of arts universities into more responsive and adaptive learning organizations (Maden, 2012; Ranczakowska, 2022b).

Entrepreneurial mindset

At its core, the entrepreneurial mindset is defined by a proactive orientation toward opportunity recognition, creativity, and the transformation of ideas into actionable outcomes (Gibb, 2002; Sarasvathy, 2001; Van de Ven, 2016). Neoliberalism, as a form of governance, reshapes not only institutions but also individual subjectivities, encouraging individuals to adopt entrepreneurial identities focused on self-management and economic productivity. In higher education, particularly within the creative industries, the entrepreneurial mindset is often framed as a set of competencies designed to help students navigate an increasingly complex and uncertain professional landscape (Bennett, 2009; Garnham, 2005). These competencies typically include adaptability, resilience, and the ability to manage risk across both economic and creative domains.

The rise of the entrepreneurial mindset in higher education can be seen as a reflection of broader neoliberal ideologies that prioritize market logic and competition. Neoliberalism has reshaped educational institutions, pushing them to operate more like businesses, where efficiency and marketable outcomes are paramount (Shore, 2010). This shift, as Harvey (2005) argues, reflects the “marketisation of everything,” including knowledge and creativity. As a result, higher education is no longer viewed primarily as a public good aimed at fostering critical thought but as a commodity designed to produce economically competitive individuals. The emphasis on entrepreneurialism within curricula reinforces this shift, encouraging students to view themselves as individual market actors rather than as part of a collective intellectual community.

In arts universities, where artistic identity and creative autonomy are paramount, the entrepreneurial mindset as an economy-based tool is often met with skepticism. Research suggests that many students perceive entrepreneurial education as conflicting with their core artistic values and the notion of art as a non-commercial, purely expressive endeavor (Ellmeier, 2003; Naudin, 2015; Ranczakowska et al., 2017). This tension reflects a broader concern within entrepreneurial education: while it offers essential skills for economic survival and career management, it may also challenge the artist’s sense of identity, values, and mission. However, this study moves beyond the binary opposition of artistic integrity versus economic reality. We propose that when critically engaged with, the entrepreneurial mindset has the potential to facilitate personal and collective knowledge creation, rather than simply serving as a vehicle for economic empowerment (Bennett, 2008; Gibb, 2002).

We argue that entrepreneurial mindset is not merely a set of external skills for managing one’s career; it is a mode of thinking that promotes critical reflection on one’s practice, adaptability, and innovation. For arts students, this mindset can be leveraged to enrich artistic practice, allowing for a deeper engagement with creative processes while simultaneously preparing for the complexities of professional life. The entrepreneurial mindset encourages students to not only identify opportunities but also to engage in reflective inquiry about how these opportunities align with their personal values, artistic identity, and professional aspirations (McGrath and MacMillan, 2021).

Within arts universities, the entrepreneurial mindset becomes particularly significant in the context of knowledge management, where it serves as a facilitator of individual learning and organizational growth. By fostering a proactive, reflective approach to professional development, the entrepreneurial mindset enables students to navigate the evolving demands of the creative industries while contributing to the co-construction of knowledge within Communities of Practice (CoPs) (e.g., Peltonen and Lämsä, 2004). This dual role—as both a tool for individual empowerment and a catalyst for collective knowledge creation—positions the entrepreneurial mindset as a critical element in the transformation of arts universities into learning communities.

Communities of practice (CoPs)

Communities of Practice (CoPs) are social learning structures that emerge when individuals engage in shared practices and collective knowledge creation. Wenger (1998) defines CoPs as groups characterized by mutual engagement, joint enterprise, and shared repertoire—elements that are critical for the development and sharing of both tacit and explicit knowledge within a community. In arts universities, CoPs are integral to the transmission of artistic knowledge, which is often deeply embedded in practice and not easily codified in formal educational structures (Polanyi, 1962; Wenger, 1998).

CoPs in the arts are typically centered around mentor-student relationships, where knowledge is transferred through observation, imitation, and direct participation in artistic activities (Orning, 2019; Ranczakowska, 2022a). These communities often extend beyond the confines of the university, connecting students with professional networks in the creative industries. The informal, practice-based learning that occurs within CoPs is essential for the development of technical skills, creative intuition, and professional identity (Bennett and Male, 2017).

However, the integration of entrepreneurial education into arts universities introduces a new dimension to CoPs. In arts universities, Communities of Practice (CoPs) emerge as dynamic spaces for knowledge sharing, mentorship, and collaboration. Wenger (1998) defines CoPs as groups where individuals learn collectively through shared practices and engage deeply with mutual learning goals. This study emphasizes that in arts universities, CoPs are integral to the dissemination of tacit knowledge, especially through informal structures such as peer collaboration and mentor-student interactions. CoPs also facilitate knowledge co-creation, allowing students to test entrepreneurial concepts within their artistic frameworks, thereby reshaping both their professional and creative identities.

The RENEW project (Reflective Entrepreneurial Music Education Worldclass), a collaboration involving the Royal Academy of Music in Aarhus, the Royal Conservatoire The Hague, and the Association Européenne des Conservatoires (AEC), provides a practical example of this dynamic. RENEW promoted entrepreneurial mindset as a vital component of higher music education, fostering collaboration and innovation through initiatives like student bootcamps and teacher training.

The Secum project (Self-Curating Musician), led by the KASK & Conservatorium in Ghent, employed design-thinking principles to help students navigate entrepreneurial challenges. It empowered young musicians to develop entrepreneurial skills and self-curate their careers, demonstrating how CoPs can provide a structured space for developing both creative and professional agency.

Similarly, the Glomus network, involving conservatories globally, focuses on intercultural collaboration and interdisciplinary learning. Glomus provides opportunities for students to participate in cross-cultural projects, collaborative performances, and workshops, encouraging adaptability and entrepreneurial thinking within diverse artistic and cultural contexts.

These initiatives exemplify how CoPs in arts universities function as transformative spaces, bridging the gap between artistic practice and entrepreneurial competence while addressing the unique needs of creative disciplines. The combination of tacit and explicit knowledge in these contexts facilitates knowledge co-creation, where students can implement their entrepreneurial competences into real life context, reshaping both their professional and creative identities.

A key insight that emerges from our preliminary observations is the potential for entrepreneurial mindset to serve as a facilitator of knowledge co-construction rather than as a disruption. When properly integrated, entrepreneurial competencies can encourage students to view their creative practice through a lens of innovation and value creation moving away from the constructed artistic integrity versus economic reality dualism. This aligns with Wenger’s emphasis on mutual engagement—where collective action in CoPs can be redirected toward exploring how artistic work intersects with external professional environments. The process of integrating entrepreneurial mindset into CoPs requires that students not only engage with new skill sets but critically reflect on how these skills support or challenge their artistic identities.

This dynamic also ties into Dewey (1986) and Dewey (1938) conception of participation as a precursor to responsibility and engagement. When students take ownership of their entrepreneurial learning within CoPs, they are more likely to contribute to the co-creation of knowledge, driving both individual and collective outcomes. However, for this transformation to take place, it is essential that CoPs provide space for critical reflection on how entrepreneurial activities align with students’ broader artistic missions. Without this reflective component, entrepreneurial education risks being perceived as an imposed structure rather than a meaningful addition to the students’ learning journey within the overall knowledge dynamic of arts university organization.

SECI model of knowledge management

The SECI model of knowledge management, developed by Nonaka and Takeuchi (1995), provides a framework for understanding how knowledge is generated, shared, and applied within organizations. The SECI model outlines four modes of knowledge conversion: Socialization, Externalization, Combination, and Internalization. These processes represent the dynamic interplay between tacit and explicit knowledge, both at the individual and collective levels which is important for our research which addresses the individual mindset, learning and knowledge sharing on the one hand and collective organizational learning and knowledge management on the other. It also allows us to examine - through the four elements - the co-creative aspects as they emerge within the communities of practice and other shared experiences within chosen organizations.

Firstly, socialization involves the transfer of tacit knowledge through shared experiences and interactions. In the context of arts universities, socialization occurs within CoPs, where students learn through observation, imitation, and participation in artistic practice. Tacit knowledge is passed from mentors to students in informal settings such as studios, rehearsals, and performances, allowing for the development of creative intuition and technical skills.

Secondly, externalization is the process of articulating tacit knowledge into explicit concepts, making it accessible and transferable to others. This phase is critical in entrepreneurial education, where students are encouraged to externalize their creative ideas in the form of business plans, project proposals, or marketing strategies as well as being able to navigate complex cross-sectoral environments and adapt their ideas to the diversity of these. Externalization bridges the gap between artistic practice and entrepreneurial action, enabling students to transform their creative visions into actionable projects.

Thirdly, combination refers to the synthesis of explicit knowledge from various sources to create new knowledge. In arts universities, combination occurs when students integrate entrepreneurial strategies with their artistic practice, often through interdisciplinary collaborations. For example, a student might combine their knowledge of performance art with skills in process design or project management to create a sustainable model for a creative project. Combination in essence supports systems thinking where one is capable of organizing diverse knowledge into one actionable structure.

Fourthly, internalization is the process by which explicit knowledge is absorbed and becomes part of an individual’s tacit knowledge base. In the context of entrepreneurial education, internalization occurs when students begin to incorporate entrepreneurial competencies into their artistic practice, allowing them to navigate the professional landscape more easily and effectively. Over time, entrepreneurial skills such as networking, project management, and personal branding become internalized as part of the students’ broader creative identity.

The SECI model offers a valuable lens for understanding how knowledge is co-created within CoPs, particularly when entrepreneurial education is integrated into the learning environment. By facilitating knowledge sharing and the conversion of tacit knowledge into explicit knowledge (and vice versa), the SECI model follows the knowledge flow, allowing students to engage in both creative and entrepreneurial activities in a more cohesive and integrated manner.

Integrating the frameworks

The integration of entrepreneurial mindset, Communities of Practice (CoPs), and the SECI model forms the theoretical backbone of this study. Together, these frameworks offer a comprehensive approach to understanding how entrepreneurial education and collaborative practices can facilitate personal transformation, collective learning, and knowledge co-creation in artistic and professional contexts.

The entrepreneurial mindset encourages students to adopt a proactive, reflective approach to their professional development, fostering a capacity for innovation and adaptability. Within CoPs, this mindset can be leveraged to enhance both individual and collective learning, as students collaborate on projects that require them to integrate their artistic skills with entrepreneurial strategies. The SECI model, in turn, provides a mechanism for understanding how knowledge is created, shared, and applied within these communities, allowing for a dynamic interplay between tacit and explicit knowledge that supports both artistic excellence and professional growth.

Ultimately, this theoretical framework positions entrepreneurial education as a tool for transforming arts universities into learning organizations that are responsive to both individual needs and broader societal challenges. By fostering a more holistic approach to knowledge management, one that encompasses both artistic and entrepreneurial competencies, arts universities can better equip students to navigate the complexities of the creative industries while contributing to the co-creation of knowledge within their communities.

Methodology and data

This section outlines the methodological choices underpinning the study, highlighting how the research design aligns with the theoretical and practical demands of the research questions. Conducted at two leading arts universities—the Estonian Academy of Music and Theatre (EAMT) and the University of the Arts Helsinki (Sibelius Academy)—the study aimed to explore how entrepreneurial mindset and education contribute to knowledge management, individual learning, and peer collaboration within Communities of Practice (CoPs).

Rather than conducting a comparative analysis between EAMT and Sibelius Academy, the study approached both institutions as part of a unified data pool. This decision was guided by their shared emphasis on integrating entrepreneurial and artistic education within similar cultural and educational contexts. Treating the responses as a single dataset allowed us to move beyond institutional differences and focus on the participants’ personal experiences, which are central to understanding how entrepreneurial education interacts with artistic identities and professional development. By integrating data from both institutions, we captured a holistic view of how entrepreneurial education functions within arts universities, highlighting shared challenges, opportunities, and the dynamic interplay between individual learning and organizational knowledge creation.

The participants included undergraduate (BA), postgraduate (MA), and some doctoral (PhD) students enrolled in music programmes at both institutions. Data were collected as part of an individual PhD studies of the authors as well as two larger projects within ActinArt network (of which both EAMT and Sibelius Academy were members at the time) examining the integration of entrepreneurial education within artistic curricula.

Research approach

This study employed a social constructionist approach, grounded in interpretivist epistemology (Berger and Luckmann, 1991). The context of arts universities, where learning and knowledge creation are deeply rooted in artistic practice and tacit knowledge, necessitated a perspective capable of capturing the richness and complexity of these experiences. This approach enabled us to interpret the meanings that students and educators ascribe to entrepreneurial education and the entrepreneurial mindset within their institutional and social environments. Rather than simply documenting facts, the aim was to uncover the deeper narratives and perspectives that shape their engagement with these concepts. By adopting a qualitative, multi-method design, the study offers a comprehensive and nuanced understanding of the phenomena under investigation, emphasising lived experiences and individual perceptions.

Data collection

We collected the data between 2020 and 2022 through three primary methods: semi-structured interviews, focus groups, and survey-interviews. We choose these methods to elicit both explicit and tacit knowledge, capturing the multifaceted experiences of participants in arts education.

Our data collection methods included:

a) Semi-structured interviews

Semi-structured interviews were conducted with 16 participants, including BA, MA, and PhD students, as well as alumni and institutional leaders. These interviews offered in-depth insights into participants’ individual experiences with entrepreneurial education, particularly its integration with artistic identity and its influence on professional goals. This method enabled a nuanced exploration of how entrepreneurial competencies intersect with students’ personal and professional development in the arts.

b) Focus groups

Five focus groups were held with a total of 41 participants, primarily comprising BA and MA students. These discussions provided a collective perspective on peer learning, Communities of Practice (CoPs), and the role of entrepreneurial education in fostering collaboration and professional growth. Focus groups also highlighted shared challenges and opportunities, particularly in navigating the demands of entrepreneurship within the context of artistic education, offering a richer understanding of group dynamics and collective learning experiences.

c) Survey-interviews

Survey-interviews were administered to 166 BA and MA students using both online and paper formats. The survey employed a mixed-methods approach, blending quantitative and qualitative questions to capture both broad trends and detailed reflections. This method allowed for the collection of a wide range of data on students’ perceptions of entrepreneurial education, their engagement with entrepreneurial skills, and the challenges they face in applying these skills to their artistic practices.

During interviews and focus groups, rather than following predefined themes, we allowed the questions to evolve organically as insights emerged from participant responses. Our process of inquiry was iterative, with reflections from early interactions shaping subsequent data collection. To explore students’ experiences with entrepreneurial education, we asked open-ended questions, such as: “How do you perceive the role of entrepreneurial education in your studies?”, “Can you describe any challenges you face when integrating entrepreneurial skills into your artistic work?”, and “How does entrepreneurial education impact your artistic practice?” These exploratory questions encouraged participants to articulate their own meanings and interpretations, allowing for the emergence of patterns and shared understandings.

As the dialogue progressed, we invited participants to reflect on their conceptualisations of the entrepreneurial mindset. We facilitated this reflection through questions such as “What does the entrepreneurial mindset mean to you?”, “How do you perceive the role of entrepreneurial education in your field?”, and “What traits or skills do you associate with the entrepreneurial mindset?”. This approach enabled a co-constructed understanding of the entrepreneurial mindset as it emerged within the context of arts education.

Knowledge-sharing practices emerged as significant elements in participant narratives. We further asked students to elaborate on their experiences in collaborative practices and informal interactions. Our questions included: “How do you and your peers share knowledge and skills within your programme?”, “What role do informal discussions or rehearsals play in shaping your learning?”, and “How has collaboration with peers influenced your learning or professional development?”.

Knowledge sharing also surfaced as a central point of discussion. Participants shared examples of knowledge transfer through reflective storytelling, and we further inquired about it by asking questions like: “Can you describe an instance where you shared knowledge with your peers or mentors?”, “What barriers do you experience when sharing your (entrepreneurial) ideas?”, and “How do trust and competition affect knowledge sharing in your learning community?”. These discussions revealed nuanced understandings of the conditions and contexts that enable or inhibit effective knowledge sharing.

By maintaining a fluid, emergent approach to data collection, we captured a holistic and dynamic view of students’ experiences, perceptions, and practices related to entrepreneurial education and the entrepreneurial mindset within arts universities. Our emphasis on participant-driven narratives and meaning-making prioritised lived experience of the participant.

The average duration of interviews and focus groups was approximately one and a half hour. Survey questions included both multiple-choice and open-ended formats, allowing participants to elaborate on their experiences.

Research sites and participants

The study was conducted at EAMT and Sibelius Academy, institutions recognised for their focus on fostering artistic talent and integrating entrepreneurial education. Participants included students, alumni, deans, rectors, and professionals from organizations such as Music Finland and Music Estonia. This diversity ensured a broad perspective on the intersection of entrepreneurial education, artistic identity, and knowledge management.

The study’s participants were predominantly from music programmes, encompassing a variety of specialisations (e.g., classical performance, composition, audiovisual composition, musicology, pedagogy, and arts management). Contextual nuances, such as differences in institutional culture and language, were considered. For example, surveys in Estonia were conducted in Estonian and English, while those in Finland were primarily in English. This multilingual approach ensured inclusivity and accuracy in data collection.

Analytical approach

Thematic analysis, based on Braun and Clarke (2006) framework, was used to identify patterns and themes in the data. The analysis involved:

a) Familiarisation: Reading transcripts to gain an overview of participant narratives.

b) Coding: Systematically categorising data based on recurring ideas.

c) Theme Development: Grouping codes into overarching themes.

d) Refinement: Cross-referencing themes with theoretical constructs.

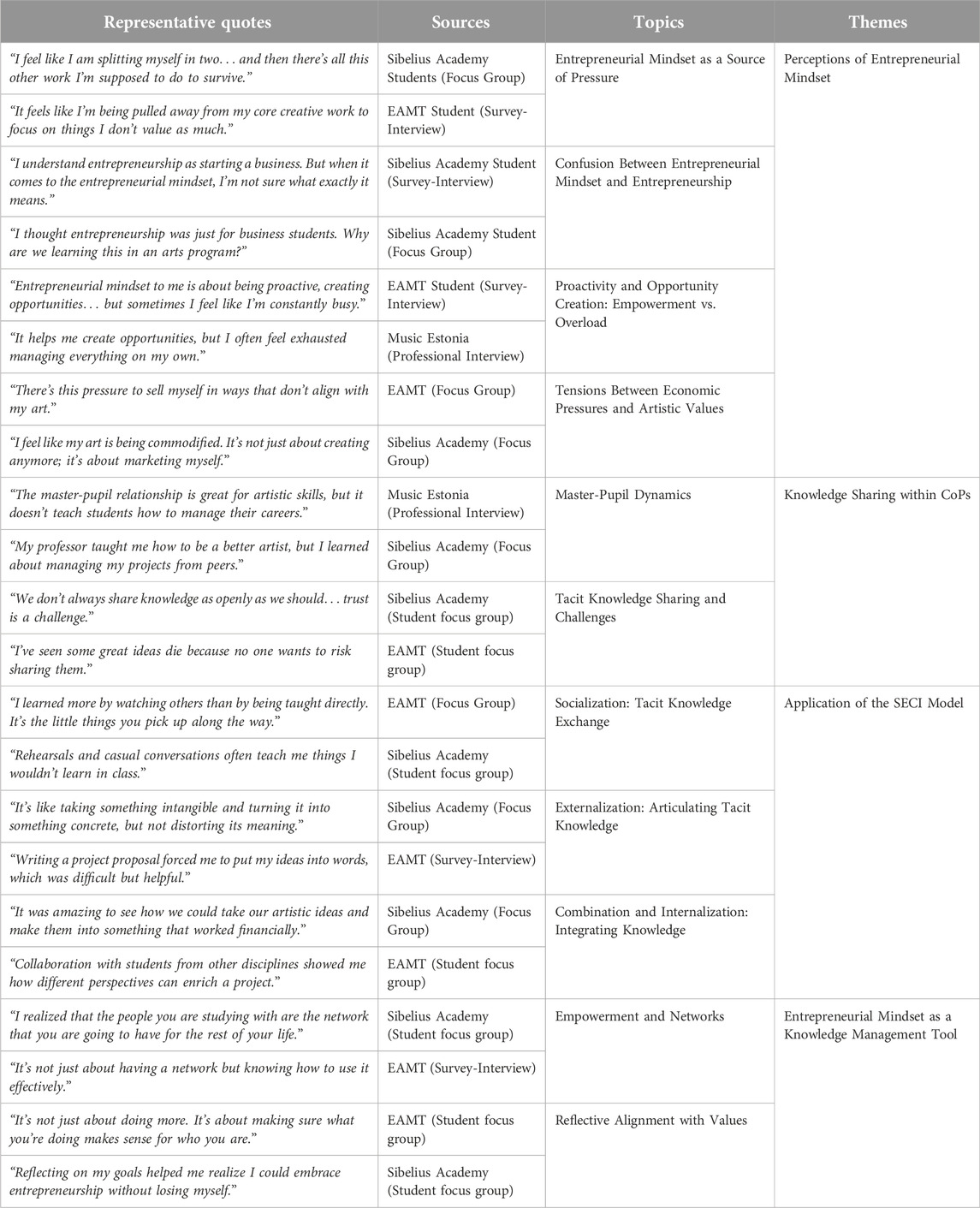

The primary themes identified—Perceptions of the Entrepreneurial Mindset, Knowledge Sharing within CoPs, Application of the SECI Model, and Entrepreneurial Mindset as a Knowledge Management Tool—reflect the dynamic relationship between entrepreneurial education and artistic practice. These themes are further elaborated in the findings section, supported by detailed examples in Table 1.

Reflexivity and ethical considerations

Reflexivity was central to the research, ensuring awareness of our positionality as researchers and its impact on the data interpretation (e.g., Moisander and Valtonen, 2006). Ethical considerations, such as confidentiality, anonymity, informed consent, and voluntary participation, were strictly adhered to, with special attention to the power dynamics between students and educators. We continuously reflected on our positionality as researchers and the potential influence our interpretations had on the data. This reflexivity was particularly important given the subjective nature of the experiences we were studying, and the close relationship between the researchers and the research sites.

Ethical considerations were also carefully addressed, ensuring the confidentiality and anonymity of participants throughout the research process. All participants provided informed consent, and their participation was voluntary. Sensitive to the power dynamics inherent in student-educator relationships, we took care to ensure that students felt comfortable sharing their honest perspectives without fear of repercussions.

This methodological approach allowed us to explore the complex, multi-layered realities of how entrepreneurial education is experienced and perceived within arts universities. By employing a qualitative, constructionist methodology, we were able to capture not only the explicit knowledge shared by participants but also the tacit, often unspoken dynamics that shape their learning experiences and professional development. The use of thematic analysis helped us to synthesize these insights into coherent themes, which are explored in detail in the subsequent sections of this paper.

Research findings

This section presents the qualitative findings derived from interviews, focus groups, and survey responses with students, alumni, and faculty at EAMT and Sibelius Academy. The findings explore how the entrepreneurial mindset, Communities of Practice (CoPs), and the SECI model function within these arts universities, focusing on their impact on students’ artistic identities and professional development.

The data revealed four interrelated themes: Perceptions of the Entrepreneurial Mindset, Knowledge Sharing within CoPs, Application of the SECI Model, and Entrepreneurial Mindset as a Knowledge Management Tool. These themes illuminate the dynamic ways in which entrepreneurial education interacts with the tacit and explicit knowledge processes central to artistic practice, as well as the tensions and opportunities that arise when entrepreneurial competencies are integrated into arts curricula.

To provide clarity and structure, Table 1 offers a detailed overview of the findings, including representative quotes and data sources. This table serves as a foundational reference for interpreting the themes presented in this section, enabling readers to connect the summarised findings with specific participant experiences. While the table provides granular evidence, the narrative below synthesises and interprets the data, emphasising patterns, theoretical connections, and implications for arts education.

Each theme highlights specific aspects of this interaction:

Perceptions of the Entrepreneurial Mindset examines students’ ambivalence towards entrepreneurial education, reflecting both its potential for empowerment and its perceived conflicts with artistic identity. Knowledge Sharing within CoPs explores how tacit knowledge exchange and mentorship shape learning, while also addressing barriers such as trust issues and competition. Application of the SECI Model analyses how knowledge flows within these institutions, identifying unique challenges in the externalisation and combination of artistic and entrepreneurial knowledge. Entrepreneurial Mindset as a Knowledge Management Tool investigates how this mindset fosters professional networks, aligns with personal values, and supports knowledge creation and transfer.

Together, these themes offer a nuanced understanding of how entrepreneurial education operates within the complex learning environments of arts universities, supported by frameworks such as the SECI model (Nonaka and Takeuchi, 1995) and Wenger (1998) concept of CoPs. This section synthesises these findings, emphasising their relevance to the broader goals of integrating entrepreneurial competencies into artistic education.

Description of findings perceptions of entrepreneurial mindset

Students expressed a range of ambivalent feelings about the entrepreneurial mindset. While many acknowledged its potential to foster proactivity and opportunity creation, they also identified significant challenges, particularly in reconciling entrepreneurial demands with their core artistic identities. For example, students often felt that entrepreneurial education added a burdensome layer of responsibilities, detracting from their creative work and raising concerns about losing focus on their artistic goals. This finding aligns with Kuznetsova-Bogdanovitsh (2022) argument that entrepreneurial competencies can conflict with students’ intrinsic artistic values, particularly when introduced without sufficient contextualization within artistic practices.

Another common theme was confusion between the concepts of entrepreneurial mindset and entrepreneurship. Participants often conflated the two, perceiving entrepreneurial education as narrowly focused on business creation. This misunderstanding sometimes resulted in disengagement from entrepreneurial education, as students struggled to see its relevance to their artistic aspirations. The distinction between entrepreneurship as business creation and the entrepreneurial mindset as a broader set of cognitive and behavioral skills is critical (Daspit et al., 2023), as it underscores the mindset’s relevance to adaptability and innovation beyond economic goals.

Despite these challenges, some participants appreciated the entrepreneurial mindset for its emphasis on proactivity, which they saw as an essential skill in navigating the limited opportunities within the arts. This perspective resonates with Sarasvathy (2001) theory of effectuation, which emphasizes the importance of adaptability and opportunity creation in navigating uncertain environments. However, this empowerment often came at the cost of overload, as students described the pressures of managing multiple roles without adequate support.

These tensions were further intensified by the perceived conflict between economic pressures and artistic values. Many participants expressed discomfort with aligning their creative practices to market-driven expectations, fearing that such alignment could commodify their art. This perspective aligns with critiques of neoliberal pressures in the creative industries, which often compel artists to balance artistic integrity with marketability (Kunst, 2015; Bennett, 2008; Ellmeier, 2003). These concerns also echo challenges identified in the literature regarding the integration of entrepreneurial education into arts programmes, particularly the difficulty of doing so in ways that preserve students’ artistic integrity. This tension continues to pose a significant barrier to the successful implementation of entrepreneurial education within arts universities.

Knowledge sharing within communities of practice (CoPs)

CoPs served as critical spaces for knowledge sharing, particularly for the exchange of tacit knowledge central to artistic development. Participants highlighted the importance of informal interactions, such as rehearsals or collaborative projects, as key moments for acquiring skills and insights that formal training often overlooked. This finding aligns with Wenger (1998) and Herne (2006) conception of CoPs as learning environments where tacit knowledge is transmitted through shared practices and social engagement.

However, the traditional master-pupil dynamic prevalent in artistic training showed limitations in preparing students for the entrepreneurial aspects of their careers. While this relationship was effective for developing artistic skills, it often did not address the practicalities of project management, self-promotion, or networking. Participants also noted a reluctance to share entrepreneurial knowledge within CoPs. This hesitation often stemmed from competitive dynamics, trust issues, and fear of criticism, all of which hindered open collaboration. These challenges align with Wenger (1998) concept of Communities of Practice, which emphasises the role of trust and mutual engagement in facilitating effective knowledge sharing. Within CoPs, a lack of trust can create barriers to the free flow of knowledge, particularly in contexts where collaboration intersects with competitive pressures.

Application of the SECI model

The SECI model provided a useful framework for understanding how entrepreneurial knowledge was created and managed within CoPs. In the socialization stage, students absorbed tacit knowledge through observation and participation in artistic communities. These interactions allowed them to acquire practical insights informally, which were often more impactful than formal lessons. This aligns with Nonaka and Takeuchi (1995) emphasis on socialization as the foundation for tacit knowledge exchange, particularly in environments where collaboration and mentorship play central roles.

The externalization stage, where tacit knowledge is made explicit, proved more challenging. Participants found it difficult to formalize deeply personal artistic knowledge into entrepreneurial concepts, such as business plans or marketing strategies. This reflects the tension between the abstract, personal nature of artistic knowledge and the structured demands of entrepreneurial education (Kuznetsova-Bogdanovitsh, 2022).

The combination stage was particularly evident in interdisciplinary collaborations, where students synthesized artistic and entrepreneurial knowledge to create innovative projects. Finally, internalization occurred as students began to embed entrepreneurial skills into their creative practices, approaching their work with greater strategic awareness. These findings suggest that the SECI model, while effective, requires adaptation to address the specific challenges of knowledge creation within the arts.

Entrepreneurial mindset as a knowledge management tool

When critically engaged with, the entrepreneurial mindset emerged as a tool for fostering empowerment, expanding professional networks, and facilitating knowledge management. Participants described how their networks, built during their studies, served as valuable resources for future collaborations and career opportunities. This aligns with Gibb (2002) argument that entrepreneurial competencies should emphasize relational and social dimensions, particularly in fields where collaboration drives innovation.

Reflective practices were also crucial in ensuring that entrepreneurial activities aligned with personal and artistic values. By critically examining their goals, participants were able to integrate entrepreneurial skills into their practice without compromising their creative identities. Sarasvathy (2001) concept of effectuation supports this approach, emphasizing the importance of aligning entrepreneurial actions with individual values and long-term goals.

Discussion

Navigating the tension between artistic integrity and economic realities

The integration of entrepreneurial education within arts universities exposes a profound tension between the preservation of artistic integrity and the demands imposed by economic realities. This dualism is not merely a pedagogical challenge but reflects the deeper entrenchment of neoliberal ideologies in higher education (Ranczakowska, 2023; Shore, 2010). Neoliberalism, as a pervasive force, reconfigures educational institutions into market-driven entities, prioritizing efficiency, competitiveness, and economic utility over critical inquiry and creative exploration (Brown, 2015; Foucault, 1979; Harvey, 2005).

Students in our study frequently articulated feelings of discomfort and dissonance when confronted with the entrepreneurial imperative. They perceived entrepreneurship as an external imposition that threatens to commodify their artistic practice, aligning with Kunst (2015) critique of the fetishization of artistic labor under capitalism. Kunst argues that the proximity of art and capitalism leads to the absorption of artistic autonomy into market logic, where the artist becomes a “virtuoso worker” expected to constantly perform and produce within the parameters of economic value.

One Sibelius Academy student expressed this tension poignantly:

“There’s this pressure to sell yourself, and that can feel really uncomfortable when all you want to do is create music or art. It’s like my art is being turned into a product, and that’s not why I became an artist.” (Sibelius Academy, survey-interview)

This sentiment echoes the crisis of subjectivity described by Kunst (2015) and the internalization of neoliberal values that reshape individuals into entrepreneurial subjects (Bröckling, 2015; Foucault, 1979). The students’ struggle reflects the broader impact of neoliberalism as a hyperobject (Morton, 2013), an omnipresent force that infiltrates personal identities and institutional practices, often making it difficult to envision alternative modes of being (Fisher, 2009; Graeber, 2018).

Furthermore, the neoliberal narrative of inevitability—there is no alternative—reinforces the notion that embracing entrepreneurial competencies is the only viable path to success in the creative industries (Fisher, 2009). This narrative marginalizes other values and practices that prioritize creativity, social engagement, and critical reflection, aligning with Mark Fisher’s concept of “capitalist realism.”

Diverse perceptions of the entrepreneurial mindset among students and educators

Despite the pervasive influence of neoliberalism, perceptions of the entrepreneurial mindset among students and educators are not monolithic. While some view it as a constraining force, others perceive it as an opportunity for empowerment and creative expansion. This diversity highlights the complexity of integrating entrepreneurial education into arts curricula.

Educators who critically engage with entrepreneurial concepts often strive to contextualize them within artistic practice, aiming to reconcile economic competencies with creative values. As one educator noted:

“We try to teach entrepreneurship not as a way to commercialize art but as a set of tools that can help students realize their creative visions and make a positive impact.” (Educator interview)

This approach aligns with Freire (1970) concept of critical pedagogy, advocating for education that empowers students to question dominant ideologies and develop a critical consciousness. By reframing entrepreneurship as a means to enhance creative agency rather than as an end in itself, educators can help students navigate the tensions between market demands and artistic integrity. Weeks (2011) calls for rethinking the value of labor beyond its economic output, a perspective that resonates with artists who often resist reducing their creative work to a commodity. By embracing antiwork politics, arts universities can equip students with the critical tools to both navigate and challenge the systems that pressure them to commercialize their art, prioritizing creative freedom and personal fulfillment over financial gain.

Students who adopt this reframed perspective often find that entrepreneurial skills can indeed augment their artistic practice. One EAMT student shared:

“When I started thinking of entrepreneurship as a way to support my art rather than sell it out, I felt more in control. It’s about using these skills to bring my ideas to life on my own terms.” (EAMT, survey-interview)

This reflects the potential for students to resist the neoliberal construction of the “entrepreneurial self” (Bröckling, 2015) by integrating entrepreneurial competencies in a manner that aligns with their personal values and artistic identities.

Entrepreneurial mindset beyond economic empowerment and self-efficacy

When critically embraced, the entrepreneurial mindset offers benefits that go beyond economic empowerment and self-efficacy. It fosters innovation, resilience, and creative problem-solving—qualities essential for navigating today’s complex creative landscape (Bacigalupo et al., 2016a; Bacigalupo et al., 2016b; Sarasvathy, 2001). Students in this study reported that adopting an entrepreneurial mindset enabled them to:

• Initiate Innovative Projects: By creating unique artistic endeavors—such as interactive public installations or multimedia performances—they enhanced their agency and took control of their artistic narratives.

• Engage in Cross-Disciplinary Collaborations: Collaborating with peers from other fields, such as other fields of the arts but also technology or environmental science, expanded their perspectives and networks, leading to groundbreaking work that transcended traditional artistic boundaries.

• Cultivate Adaptability and Critical Thinking: When faced with challenges such as shifting to virtual platforms during the pandemic, students demonstrated the agility to pivot creatively, ensuring their art remained relevant and impactful.

One student emphasized these broader benefits:

“Entrepreneurial skills have helped me think more strategically about my work. It’s not just about making money; it’s about finding innovative ways to express myself and connect with others.” (Sibelius Academy, focus group)

This perspective aligns with Mezirow (1991) theory of transformative learning, which emphasizes critical reflection that leads to personal growth and empowerment. By fostering such capacities, the entrepreneurial mindset contributes to the development of adaptive expertise (Bereiter, 2002), enabling students to innovate within their artistic domains.

Alignment between entrepreneurial mindset and artistic identity can be achieved through targeted pedagogical strategies that integrate entrepreneurial skills without compromising core artistic values and adding pressure. By framing entrepreneurial mindset as a tool for creative expansion rather than purely economic gain, educators can support students in developing both professional and artistic competencies. For instance, in CoPs, mentorship programs and project-based learning encourage students to apply entrepreneurial principles in ways that enhance their artistic practice with a plethora of diverse potential outcomes.

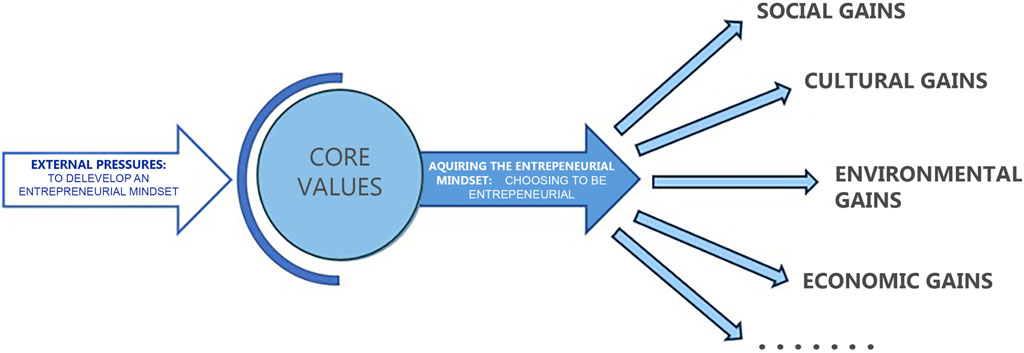

Figure 1 illustrates how external pressures, such as societal or market demands, can be transformed into opportunities by anchoring decisions in core values. This alignment allows individuals to adopt an entrepreneurial mindset as a choice rather than a necessity, enabling them to achieve diverse outcomes such as social, cultural, environmental, and economic gains among others. As Naudin (2015) emphasizes, entrepreneurship in the arts can prioritize creative and societal imperatives over purely economic objectives.

Communities of Practice (CoPs) provide a fertile ground for the application and exploration of the entrepreneurial mindset, particularly when entrepreneurial education projects are conceived as more transient or flexible CoPs. Within CoPs, students, educators, and industry professionals collaboratively engage in knowledge exchange, and the introduction of entrepreneurial thinking adds a dynamic layer to this interaction. Entrepreneurial education, when embedded within CoPs, allows students to experiment with opportunity recognition, risk-taking, and innovation in a supportive, practice-based environment. These educational projects encourage students to apply entrepreneurial principles in real-time, fostering not only individual growth but also collective learning and adaptation within the community.

However, the success of integrating the entrepreneurial mindset into CoPs largely depends on the educators’ approach and their ability to balance the often-competing demands of artistic integrity and entrepreneurial competence with the demands of the curriculum and the university at large. Educators who effectively navigate these tensions can transform CoPs into rich spaces for entrepreneurial exploration, while those who struggle may inadvertently reinforce student resistance to entrepreneurial education. This highlights the critical role of educators in shaping the entrepreneurial culture within CoPs—a factor that merits further research to understand how different pedagogical styles influence the effectiveness of CoPs as environments for entrepreneurial learning.

From individual empowerment to organizational knowledge management

The infusion of the entrepreneurial mindset into arts education has also significant implications for knowledge management and organizational learning within universities. By promoting proactive engagement and collaborative practices, it enhances the dynamics of Communities of Practice (CoPs) (Wenger, 1998).

Applying Nonaka and Takeuchi (1995) SECI model, the entrepreneurial mindset facilitates:

• Socialization: Sharing tacit knowledge through shared experiences and collaborative projects.

• Externalization: Articulating implicit artistic processes into explicit entrepreneurial strategies.

• Combination: Integrating diverse knowledge sources to create innovative solutions.

• Internalization: Embedding explicit knowledge into individual and collective practices.

This process not only empowers students but also contributes to the institution’s capacity for innovation and adaptation. As Maden (2012) suggests, transforming into a learning organization requires fostering a culture where knowledge is continuously co-created and disseminated.

However, this potential is contingent upon navigating the tensions inherent in integrating entrepreneurial education. Institutions must critically assess how neoliberal ideologies influence pedagogical approaches and strive to create spaces where alternative narratives can flourish (Kuznetsova-Bogdanovitsh, 2022; Ranczakowska, 2023). This involves challenging the notion of neoliberal inevitability and fostering critical consciousness among students and educators (Freire, 1970).

Conclusion and actionable recommendations for arts universities

Integrating the entrepreneurial mindset within Communities of Practice (CoPs) in arts universities holds transformative potential that extends beyond individual empowerment to institutional and community innovation. By aligning entrepreneurial education with students’ core artistic identities, we transcend a purely economic focus, fostering a collaborative culture of knowledge co-creation. Thus, we would like to set out some of the actionable recommendations for arts universities which could be helpful in approaching entrepreneurial education and mindset in arts universities in meaningful ways thus supporting both individual and organizational knowledge management.

As arts universities face the challenge of preparing students for increasingly complex realities, it is essential to ensure that entrepreneurial education aligns with the unique needs of artistic training. This study has shown that, while entrepreneurial education holds transformative potential, its success largely depends on how well it integrates into students’ artistic practice and identity. Universities must adopt thoughtful and context-sensitive approaches to implementing entrepreneurial education. To harness this potential effectively, arts universities should consider a set of strategies designed to not only teach entrepreneurial skills but also support students in merging these competencies with their creative identities.

The integration of entrepreneurial mindset into artistic practice within university curricula offers a promising approach to preparing students for the complexities of professional artistic careers. Rather than treating entrepreneurial education as an add-on or a separate component, it should be embedded directly into the artistic curriculum. Project-based learning presents an effective pedagogical method for achieving this integration, enabling students to develop entrepreneurial competencies through their creative work. For instance, students might design and manage real-world artistic projects—such as performances, exhibitions, or installations—that require them to engage with essential entrepreneurial tasks like budgeting, marketing, and audience engagement. By situating entrepreneurial mindset within the context of their artistic practice, students can acquire practical skills without detracting from their creative development.

However, given that many students find entrepreneurial education overwhelming, universities must enhance their support systems to facilitate a more balanced approach. Mentoring programs that provide personalized guidance are a critical component of this support. Regular check-ins with mentors can help students navigate the challenges of integrating entrepreneurship into their artistic practice, ensuring that entrepreneurial demands do not undermine their artistic integrity. These mentors—ideally professionals who have successfully blended artistic and entrepreneurial work—can offer practical advice on managing both aspects of their career while maintaining a focus on artistic development. The following strategies offer actionable steps that universities can take to ensure that entrepreneurial education fosters both professional development and artistic integrity.

In addition to mentorship, critical reflection should be a core component of entrepreneurial education within the arts. Structured opportunities for reflection allow students to examine how entrepreneurial practices align with their artistic values. By encouraging students to engage in this type of reflection, universities can support them in navigating the potential tensions between artistic integrity and commercial success (Gardner, 2009). Reflection sessions, whether through written assignments or group discussions, enable students to articulate their professional goals and make more informed decisions about how entrepreneurial activities intersect with their creative aspirations.

Finally, fostering collaborative communities of practice (CoPs) within arts programs can further support the integration of entrepreneurial mindset. These communities encourage knowledge-sharing and peer-to-peer learning, particularly around entrepreneurial skills, and can help mitigate the competitive pressures that often exist within creative disciplines. By creating spaces that promote trust and collaboration, universities can facilitate open exchanges of entrepreneurial insights alongside artistic knowledge. Group projects and interdisciplinary collaborations can serve as practical platforms for these communities, incentivizing students to work together on entrepreneurial initiatives while developing their artistic and professional networks.

In sum, embedding entrepreneurial mindset into artistic education requires a multifaceted approach, combining project-based learning with enhanced support systems, critical reflection, and collaborative communities. This holistic model not only equips students with essential entrepreneurial skills but also ensures that these skills are developed in harmony with their creative identity. Furthermore, framing the entrepreneurial mindset as a tool for collective learning enables arts universities to release neoliberal pressures that emphasize individualism and market-driven values. Through CoPs, students, educators, and professionals engage in shared experiences that enrich both personal development and the communities intellectual capital. This collaborative approach empowers students to redefine success on their own terms, valuing social and cultural contributions alongside economic viability.

By embracing this paradigm, arts universities become dynamic learning organizations that nurture creativity, critical thinking, and social engagement. This shift has profound implications for higher education, offering a pathway to resist neoliberal constraints and cultivate a more equitable and innovative educational environment. Ultimately, integrating the entrepreneurial mindset within CoPs is not just a pedagogical strategy but a transformative movement that reimagines arts education as a collaborative and empowering journey—capable of inspiring meaningful change in individuals and communities alike.

Implication for theory and further research

In the section below we outline directions for future research, focusing on adapting existing theoretical frameworks and addressing critical challenges in entrepreneurial education within arts universities.

The challenges students face during the externalisation phase of the SECI model—specifically, articulating tacit artistic knowledge into explicit entrepreneurial concepts—indicate that the model requires adaptation for creative disciplines. Traditional applications of the SECI model assume a relatively straightforward conversion of tacit knowledge into explicit forms. However, in arts education, the deeply personal and intangible nature of artistic knowledge complicates this process. Therefore, future theoretical work should focus on modifying the SECI model to account for emotional, identity-related, and value-driven factors that influence knowledge conversion in the arts. Integrating concepts from aesthetic theory or cognitive psychology could provide deeper insights into how artists process and express their tacit knowledge. These adaptations would enrich the model’s applicability to creative disciplines, making it more relevant to arts education contexts.

The study reveals that while CoPs are crucial for tacit knowledge exchange in arts universities, trust issues and competitive dynamics hinder the sharing of entrepreneurial knowledge. These barriers, often amplified by the individualistic tendencies and competitive pressures prevalent in neoliberal educational contexts, complicate the collaborative potential of CoPs. Hence, expanding CoPs theory to address these complexities is essential. Future research should explore trust-building and collaborative mechanisms within CoPs, particularly in competitive environments. This could involve drawing on social capital theory (Putnam, 2000), which examines the role of networks and trust in facilitating collective action, or collective action theory (Ostrom, 1990), which provides insights into fostering cooperation despite competing.

Finally, the tension between students’ artistic identities and the market-driven demands of entrepreneurial education highlights the pervasive influence of neoliberal ideologies on educational practices. This study highlights the importance of critically examining how these ideologies shape students’ perceptions of entrepreneurial education and their engagement with it. The narrative of resilience and adaptability risks perpetuating systems that prioritise market values over artistic integrity, leaving students to reconcile these tensions individually. Future research should incorporate critical theory perspectives (e.g., Fisher, 2009; Kunst, 2015; Giroux, 2014) into the discourse on entrepreneurial education. Such approaches can shift the focus from merely adapting to market pressures for survival to empowering artists to critically engage with and challenge these systems. By reimagining entrepreneurial education as a space for fostering systemic change rather than mere compliance, future research can contribute to the development of educational frameworks that better align with the values and aspirations of creative practitioners.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The research was conducted in compliance with the Procedure of Tallinn University Ethics Committee for the Processing of Applications for Evaluating Research, which outlines the cases in which formal ethical committee approval is not required. Based on this procedure, our study did not fall under the categories that mandate prior ethical review.

Author contributions

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct, and intellectual contribution to the work and approved it for publication.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

References

Audretsch, D. B., and Belitski, M. (2020). The role of entrepreneurship in STEM education. J. Small Bus. Manag. 58 (1), 1–20. doi:10.1007/s11187-022-00660-3

Bacigalupo, M., Kampylis, P., McCallum, E., and Punie, Y. (2016a). “Promoting the entrepreneurship competence of young adults in Europe: towards a self-assessment tool,” in Proceedings of the ICERI 2016 conference, 611–621.

Bacigalupo, M., Kampylis, P., Punie, Y., and Van den Brande, L. (2016b). EntreComp: the entrepreneurship competence framework. Luxembourg: Publication Office of the European Union.

Bennett, D. (2008). Understanding the classical music profession: the past, the present and strategies for the future. Farnham: Ashgate Publishing Limited. doi:10.4324/9781315549101

Bennett, D. (2009). Academy and the real world: developing realistic notions of career in the performing arts. Arts Humanit. High. Educ. 8 (3), 309–327. doi:10.1177/1474022209339953

Bennett, D. E., and Male, S. A. (2017). “A student-staff community of practice within an inter-university final-year project,” in Implementing communities of practice in higher education: dreamers and schemers. Editors J. McDonald, and A. Cater-Steel (Singapore: Springer Nature), 325–346.

Bereiter, C. (2002). Education and mind in the knowledge age. Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers. doi:10.4324/9781410612182

Berger, P. L., and Luckmann, T. (1991). The social construction of reality: a treatise in the sociology of knowledge. London: Penguin.

Braun, V., and Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 3, 77–101. doi:10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Bröckling, U. (2015). The entrepreneurial self: fabricating a new type of subject. London: SAGE. doi:10.4135/9781473921283

Daspit, J. J., Fox, C. J., and Findley, S. K. (2023). Entrepreneurial mindset: an integrated definition, a review of current insights, and directions for future research. J. Small Bus. Manag. 61 (1), 12–44. doi:10.1080/00472778.2021.1907583

Ellmeier, A. (2003). Cultural entrepreneurialism: on the changing relationship between the arts, culture and employment. Int. J. Cult. Policy 9 (1), 3–16. doi:10.1080/1028663032000069158a

Fisher, M. (2009). Capitalist realism: is there no alternative? Winch. Zero Books. doi:10.1163/156920612X632827

Gardner, F. (2009). Affirming values: using critical reflection to explore meaning and professional practice. Reflective Pract. 10 (2), 179–190. doi:10.1080/14623940902786198

Garnham, N. (2005). From cultural to creative industries. Int. J. Cult. Policy 11, 15–29. doi:10.1080/10286630500067606

Gibb, A. A. (2002). In pursuit of a new “enterprise” and “entrepreneurship” paradigm for learning: creative destruction, new values, new ways of doing things, and new combinations of knowledge. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 4 (3), 233–269. doi:10.1111/1468-2370.00086

Harvey, D. (2005). A brief history of neoliberalism. Oxford: Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/oso/9780199283262.001.0001

Herne, S. (2006). Communities of practice in art and design and museum and gallery education. Pedagogy, Cult. and Soc. 14 (1), 1–17. doi:10.1080/14681360500487512

Kuznetsova-Bogdanovitsh, K. (2022). “Co-constructing knowledge management practices in arts universities,” in The role of entrepreneurial mindset and education (Helsinki: Sibelius Academy University of the Arts).

Maden, C. (2012). Transforming public organizations into learning organizations: a conceptual model. Public Organ. Rev. 12 (1), 71–84. doi:10.1007/s11115-011-0160-9

McGrath, R. G., and MacMillan, I. C. (2021). What’s in a mindset? Exploring the entrepreneurial mindset. Acad. Entrepreneursh. J. 25 (4), 793–813.

Mezirow, J. (1991). Transformative dimensions of adult learning. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. doi:10.1177/074171369204200309

Morton, T. (2013). Hyperobjects: philosophy and ecology after the end of the world. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Naudin, A. (2015). Cultural entrepreneurship: narratives, identities and contexts. Int. J. Entrepreneurial Behav. and Res. 21 (2), 243–262. doi:10.1504/IJEV.2017.10006932

Nonaka, I., and Takeuchi, H. (1995). The knowledge creating company: how Japanese companies create the dynamics of innovation. New York: Oxford University Press.

Orning, T. (2019). Professional identities in progress – developing personal artistic trajectories. Int. J. Music Educ. 38 (2), 1–15.

Ostrom, E. (1990). Governing the commons: the evolution of institutions for collective action. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.2307/3146384

Peltonen, T., and Lämsä, T. (2004). Communities of practice’ and the social process of knowledge creation: towards a new vocabulary for making sense of organizational learning. Problems Perspect. Manag. 2.

Polanyi, M. (1962). Personal knowledge: towards a post-critical philosophy. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Putnam, R. D. (2000). Bowling alone: the collapse and revival of American community. New York: Simon & Schuster.

Ranczakowska, A. M. (2022a). “Hidden curriculum in arts management – perspectives on the learner’s identity, community building, and the activist mindset,” in Managing the arts 4. Editors A. Jyrämä, and K. Kiitsak-Prikk (Tallinn: Estonian Academy of Music and Theatre), 182–199.

Ranczakowska, A. M. (2022b). “Cultural management - transforming practices: the ecosystem in the making,” in Managing the arts 4. Editors A. Jyrämä, and K. Kiitsak-Prikk (Tallinn: Estonian Academy of Music and Theatre), 70–78.

Ranczakowska, A. M. (2023). “Mentorship for the transmodern world,” in Perspectives on mentoring in arts management. Editors A. M. Ranczakowska, and A. Jyrämä (Tallinn: Estonian Academy of Music and Theatre).

Ranczakowska, A. M., Kuznetsova-Bogdanovits, K., and Kiitsak-Prikk, K. (2017). “Entrepreneurial education in arts universities – facilitating the change of entrepreneurial mindset,” in Entrepreneurship in culture and creative industries: perspectives from companies and regions. Editors E. Innerhofer, H. Pechlaner, and E. Borin (Springer), 157–159. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-65506-2_8

Sarasvathy, S. D. (2001). Causation and effectuation: toward a theoretical shift from economic inevitability to entrepreneurial contingency. Acad. Manag. Rev. 26 (2), 243–263. doi:10.2307/259121

Shore, C. (2010). “The ‘schizophrenic university’ and the competing policy agendas for higher education reform,” in Beyond the audit culture: anthropological studies of accountability, ethics and the Academy (New York: Berghahn Books), 279–306.

Van de Ven, A. H. (2016). The innovation journey: you can’t control it, but you can learn to manoeuvre it. Innovation Organ. Manag. 19 (1), 1–4. doi:10.1080/14479338.2016.1256780

Weeks, K. (2011). The problem with work: feminism, marxism, antiwork politics, and postwork imaginaries. Durham: Duke University Press.

Keywords: entrepreneurial mindset, communities of practice (CoPs), knowledge co-creation, SECI model, arts universities

Citation: Kuznetsova-Bogdanovitsh K and Ranczakowska AM (2025) Knowledge co-creation in arts universities: the role of entrepreneurial mindset and communities of practice. Eur. J. Cult. Manag. Polic. 14:13872. doi: 10.3389/ejcmp.2024.13872

Received: 30 September 2024; Accepted: 24 December 2024;

Published: 31 January 2025.

Copyright © 2025 Kuznetsova-Bogdanovitsh and Ranczakowska. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Kristina Kuznetsova-Bogdanovitsh, a3Jpc3RpbmFrdXpuZXRzb3ZhYm9nZGFub3ZpdHNoQGdtYWlsLmNvbQ==

Kristina Kuznetsova-Bogdanovitsh

Kristina Kuznetsova-Bogdanovitsh Anna Maria Ranczakowska

Anna Maria Ranczakowska