- 1Department of Surgery, Laurentius Hospital Roermond, Roermond, Netherlands

- 2Department of General Surgery, Erasmus Medical Centre Rotterdam, Rotterdam, Netherlands

A lumbar abdominal wall hernia is a protrusion of intraperitoneal or extraperitoneal contents through a weakness in the posterior abdominal wall, usually through the superior or inferior lumbar triangle. Due to its rare occurrence, adequate knowledge of anatomy and methods for optimal diagnosis and treatment might be lacking with many surgeons. We believe a clear understanding of anatomy, a narrative review of the literature and a pragmatic proposal for a step-by-step approach for treatment will be helpful for physicians and surgeons confronted with this condition. We describe the anatomy of this condition and discuss the scarce literature on this topic concerning optimal diagnosis and treatment. Thereafter, we propose a step-by-step approach for a surgical technique supported by intraoperative images to treat this condition safely and prevent potential pitfalls. We believe this approach offers a technically easy way to perform effective reinforcement of the lumbar abdominal wall, offering a low recurrence rate and preventing important complications. After meticulously reading this manuscript and carefully following the suggested approach, any surgeon that is reasonably proficient in minimally invasive abdominal wall surgery (though likely not in lumbar hernia surgery), should be able to treat this condition safely and effectively. This manuscript cannot replace adequate training by an expert surgeon. However, we believe this condition occurs so infrequently that there is likely to be a lack of real experts. This manuscript could help guide the surgeon in understanding anatomy and performing better and safer surgery.

Introduction

A lumbar abdominal wall hernia (hereafter called lumbar hernia) is a protrusion of intraperitoneal or extraperitoneal contents [1, 2] through a weakness or rupture in the posterior abdominal wall. The diagnosis should not be confused with a herniation of the intervertebral disc at the lumbar level, confusingly also often referred to as “lumbar hernia.” Lumbar hernias are considered rare [3]. The existence of lumbar hernia was first suggested by Barbette in the late 17th century and published by Garangeot in the 18th century. Most cases have been described in men [4]. Approximately 20% of these hernias are supposed to be congenital and might be associated with other anomalies such as hydrometrocolpos and anorectal malformations [5–9]. The vast majority are acquired either primarily due to increased intra-abdominal pressure exceeding local abdominal wall strength, or secondarily due to accidental [10–12] or operative trauma [13, 14].

The inferior triangle of Petit and the superior triangle of Grynfeltt-Lesshaft are described [15, 16] as the two anatomical areas in which 95% of the cases of lumbar herniation occur, with a slight tendency towards the superior lumbar triangle [17]. The other 5% are more diffuse and should probably be considered an entirely different entity, consisting of a cicatricial hernia in the lumbar region often accompanied by bulging of the abdominal wall due to denervation disregarding any anatomical landmarks. These hernias are not within the scope of the current manuscript.

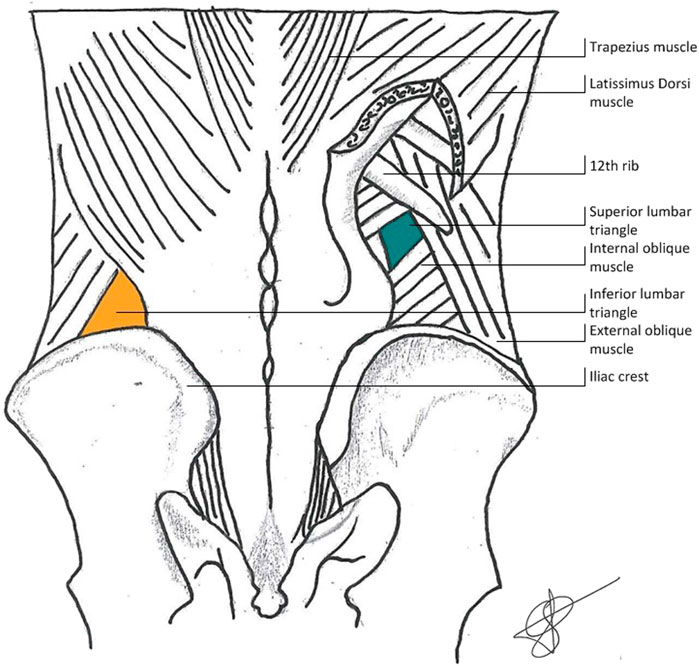

Anatomically, the superior lumbar triangle is bordered superiorly by the posterior inferior serratus muscle and the 12th rib, laterally by the posterior border of the internal oblique muscle, and medially by the anterior border of the quadratus lumborum muscle. The inferior lumbar hernia is bordered medially by the lateral border of the latissimus dorsi muscle, inferiorly by the iliac crest, and laterally by the medial border of the external oblique muscle. Predisposing factors for the occurrence of primary lumbar hernia are anatomical factors (short, obese patients with relatively horizontal ribs and therefor a larger triangle) and general factors adding to elevated intra-abdominal pressure (pregnancy, obesity, ascites) or muscle wasting (neuromuscular diseases, aging, cachexia) [2, 18]. The anatomy can be seen in Figure 1 (courtesy of van Steensel, previously published in Hernia [19]).

Clinical presentation is a patient with a protrusion in the lumbar region that grows slowly and progressively and is valsalva positive. Pain or discomfort may occur [20–22]. Incarceration and strangulation do occur regularly in up to 30% of cases at primary presentation [4, 23–28], possibly due to the specific anatomical location or due to initial underdiagnosis. Since the exact risk of incarceration is unclear but certainly not negligible, operative treatment is advocated even in mildly symptomatic cases. Ultrasound can be used for diagnosis. However, the CT scan is now considered the gold standard because of its high sensitivity of 98%, lower interobserver variance, superiority in delineating the exact anatomy including fascial and muscular defects, its ability to specify herniated contents, and its superiority in determining the presence of muscle atrophy and bulging due to denervation [18, 29–31]. MRI may be useful [32], but superiority over CT scanning has not been shown at this time. It is advised to perform a CT scan routinely in order to allow for optimal assessment of anatomy and planning of surgery [2, 18, 19].

The goal of treatment is to decrease current symptoms and to prevent complications such as incarceration or obstruction [33, 34] by eliminating the defect and reconstructing an elastic but strong abdominal wall that is able to resist future stress. At the same time, unnecessary damage to the abdominal wall should be prevented. Nerves present in proximity to the superior lumbar triangle, such as the ilioinguinal, genitofemoral and lateral femoral cutaneous nerves are at risk of perioperative injury, which should be avoided. Failure to do so might result in neuralgic pain. Due to the rare appearance of this entity, large studies comparing different surgical strategies do not exist and a clear recommendation on which surgical technique to use cannot be given. Possibly, the anatomic variability as described by Loukas [15, 16] might be clinically relevant in predicting the risk of recurrence after surgery and in choosing the optimal surgical treatment strategy. Giant hernias and diffuse incisional hernias in the lumbar region are considered a different entity, often difficult to manage. Treatment of these hernias is often unsatisfactory [30], especially if local denervation results in bulging of the abdominal wall. Careful consideration should be given when deciding if surgical treatment should be offered at all to specific individual patients. If treatment is deemed necessary, it should be performed in an expert center for abdominal wall reconstruction, offering an individualized surgical strategy based on specific anatomical and medical conditions of the individual patient, possibly necessitating fixation of the mesh to bony structures [35].

Open surgical treatment has been performed for a long time [36, 37]. The use of a musculoaponeurotic [38] or de-epithelialized dermal [39] flap to cover the defect was described in 1907 but can lead to flap ischemia, hematoma, seroma, and high recurrence rates [38, 40]. Open exploration with primary closure of the defect, reconstruction of the resilient abdominal wall, and reinforcement by placement of a mesh was introduced in 1950 [41] and has proven to be an effective strategy [18]. However, an open surgical approach of the posterior abdominal wall can be demanding due to difficulties in optimally visualizing the external edges of the fascial defect, lack of sufficient resilient abdominal wall to perform sufficient tension-free primary reconstruction [38, 40], and difficulty in positioning and fixation of an adequately sized light-weighted mesh offering sufficient overlap, preferably in the extraperitoneal space. Some authors advocate a double mesh technique in an attempt to compensate for suboptimal overlap and fixation [42]. The presence of nerves and bony structures in close proximity to the defect further limits the opportunities for reconstruction and increases the risk for inadvertent damage, potentially leading to debilitating neuralgia. Transfascial sutures should potentially be avoided in order to prevent nerve entrapment resulting in debilitating pain, although evidence is not convincing [43]. In rare cases, fixation to bony structures can be used to improve strength [35, 44]. In the case of inferior lumbar hernia, securing the mesh using bone anchors, or by passing nonabsorbable sutures through a hole drilled in the iliac crest, might be advocated. In the case of superior lumbar hernia, a nonabsorbable suture might be tied around the 12th rib. The mainstay of treatment should however consist of offering sufficient overlap of an adequately placed and secured mesh.

More recent studies show sufficient evidence to support the advantage of laparoscopic repair, offering less postoperative pain and less analgesic consumption, thus resulting in faster convalescence and lower costs [4, 45–48]. Laparoscopy also offers superior assessment of visceral contents, minimizing the probability of inadvertent injury to internal structures and allowing optimal mesh placement of an adequately sized mesh. Laparoscopic treatment can be performed using either laparoscopic intraperitoneal onlay mesh (IPOM), Transabdominal Preperitoneal Plasty (TAPP), or Total Extraperitoneal Plasty (TEP). Due to the rare occurrence of lumbar hernia and a consequent lack of sufficiently powered, well conducted, Randomized Controlled Trials, evidence concerning optimal treatment is missing. In the absence of evidence, an extrapolation of the EHS recommendations for laparoscopic treatment of ventral abdominal wall hernia [49] can be made and general principals regarding hernia repair should be followed. In that case, the use of a mesh significantly reduces the number of recurrences [50]. Closure of the fascial defect is recommended when possible, resulting in less recurrence, seroma formation, and bulging [51, 52]. Intra-peritoneal onlay mesh may result in more short-term disadvantages such as increased postoperative pain and a longer hospital stay [53, 54] compared to extraperitoneal mesh placement. It might also lead to an increase in long-term disadvantages such as an increased risk of visceral damage and increased intraperitoneal adhesion formation, potentially leading to small bowel obstruction, mesh infection, or fistula formation [55]. Although hard evidence is missing to support the superiority of extraperitoneal mesh placement [56], several studies suggest a mild preference for extraperitoneal mesh placement in order to prevent intra-peritoneal adhesions and its complications. It is likely that a flat, lightweight, macroporous, non-resorbable mesh is the optimal material to augment the abdominal wall. An adequate mesh overlap seems imminent to prevent recurrences. The mesh area-to-defect ratio appears to be more important to minimize recurrence than a standardized mesh overlap length of 5 cm [57, 58]. However, as long as hard evidence and clear guidelines concerning the optimal mesh area-to-defect ratio in lumbar hernia repair are missing, a pragmatic suggestion might be to strive for an overlap of at least 5 cm.

Theoretically, a totally extraperitoneal approach might be advocated [59, 60] as the most feasible and safe operation. When performed by an experienced and skilled surgeon, TEP offers the opportunity to avoid the abdominal cavity, potentially offering less short-term risk of intra-abdominal visceral or vascular damage and fewer intraperitoneal adhesions, decreasing long-term risk of small bowel obstruction. A second advantage might be not requiring mesh fixation, diminishing the risk of inadvertent nerve damage due to misplacement of tackers or sutures, thus preventing neuralgic pain [61]. However, TEP might be considered technically more demanding, requiring a longer learning curve compared to TAPP surgery. This longer learning curve has previously been suggested in TEP vs. TAPP treatment for inguinal hernia surgery [62, 63]. A longer learning curve might influence the potential for inadvertent damage to nerves, muscles or visceral structures before reaching proficiency. Considering the rare occurrence of lumbar hernia, the opportunities for the surgeon and their surgical team to become fully proficient in the performance of totally extraperitoneal lumbar hernia repair seem limited. TAPP surgery has been described by many authors as an effective and safe procedure [64–66]. Using an IPOM or TAPP technique, adequate fixation of the mesh seems imminent and can be performed using either absorbable tackers, nonabsorbable tackers, sutures, or fibrin glue. There is no convincing evidence to indicate the superiority of one type of fixation over another [67–69].

Materials and Methods

Due to the rare occurrence of this condition, surgeons with an extensive experience in surgical lumbar hernia repair are not likely to exist. We believe it might be useful to critically assess the sparse existing literature and suggest a relatively safe and easy surgical approach. TAPP requires limited specific expertise in lumbar hernia repair for a surgeon who is familiar with inguinal hernia TAPP repair. The anatomy can be well visualized and inadvertent visceral or nerve damage to nearby crucial structures is unlikely to occur. In lumbar hernia repair, as in larger studies concerning inguinal hernia repair, the theoretical advantages of TEP over TAPP repair preventing abdominal access have not shown major clinical relevancy and may not outweigh the disadvantages of the increased technical challenges. Therefore, we propose TAPP surgery as the first-choice technique in situations where the surgeon and surgical team are not extensively trained and experienced in TEP lumbar hernia surgery.

Step 1. After anesthesia induction, the patient is placed on a bean bag in lateral decubitus position with the affected side elevated around 60°. In our experience, a mild flexion of the table allows for an increase in working space. The patient is securely fastened to the table. We use one 12 mm camera port and two 5 mm working ports for left-sided procedure. The 12 mm port is placed in the upper left quadrant. Two 5 mm ports are placed subcostally and in the left flank.

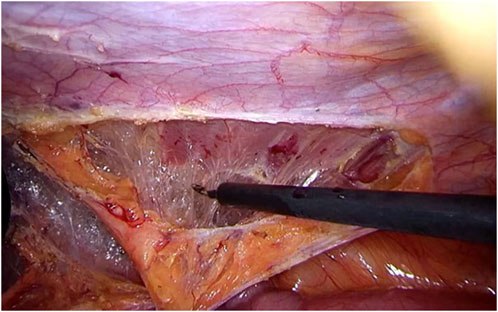

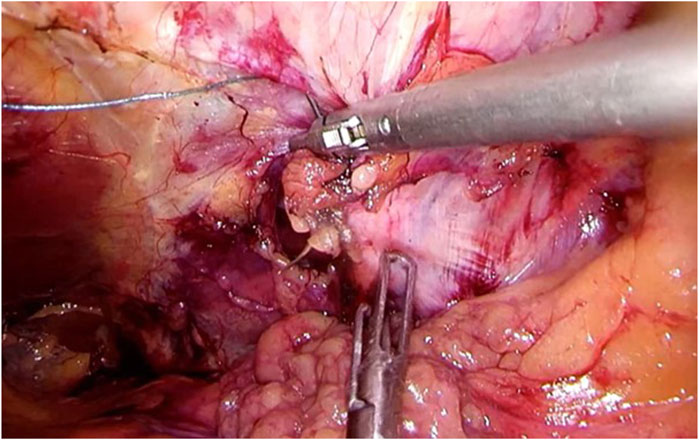

Step 2. Using sharp and diathermic dissection, the parietal peritoneum is incised just ventral to the splenic flexure. Care is taken to avoid intraperitoneal damage to spleen, greater omentum, or intestinal structures. Subsequently, the splenic flexure of the colon, parietal peritoneum, and adjacent extraperitoneal fat are mobilized from the abdominal wall musculature (Figure 2), adequately exposing the transverse fascia.

FIGURE 2. Clearing of the abdominal wall The colon, peritoneum, and adjacent extraperitoneal fat are mobilized from the abdominal wall musculature, adequately exposing the transverse fascia.

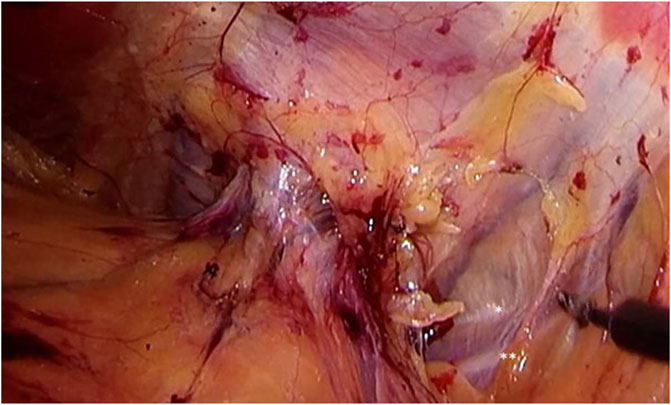

Step 3. Extending the dissection laterally and dorsally, the hernia port with protruding content can be visualized. The iliohypogastric, ilioinguinal, genitofemoral, and cutaneous femoral lateral nerves running on the ventral border of the quadratus lumborum muscle just dorsal from the hernia port can well be visualized after adequate dissection (see Figure 3).

FIGURE 3. Identification of the iliohypogastric and ilioinguinal nerves. Extending dissection laterally and dorsally, the hernia port with protruding content can be visualized. The iliohypogastric (*) and ilioinguinal (**), running on the ventral border of the quadratus lumborum muscle just dorsal from the hernia port can be well visualized. More extensive dissection will also reveal the genitofemoral and cutaneous femoral lateral nerves.

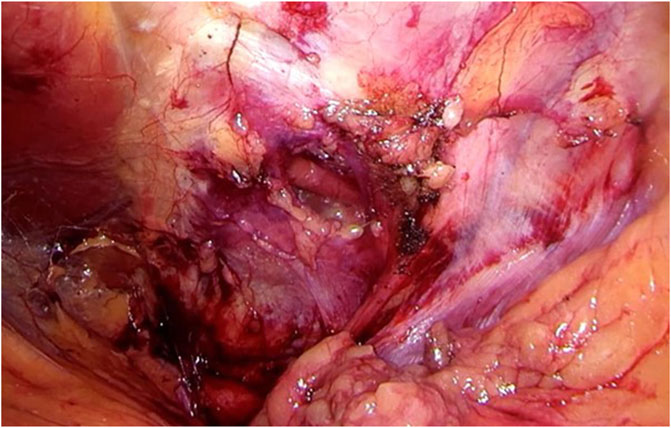

Step 4. Using gentle traction, the hernia contents can be reduced. Often, there is protrusion of extraperitoneal lipoma. It seems imminent to perform complete reduction of all hernia content in order to prevent persisting pain and bulging after surgery due to either seroma formation or the presence of a devascularized and still protruding lipoma through the defect in the abdominal wall.

Once the contents are completely reduced, anatomy can be meticulously assessed and the relation to relevant structures (such as nerves) can be well visualized. Careful interpretation of the course of the nerves seems imminent in preventing potential debilitating neuralgia by unintended nerve damage during port closure or mesh placement (see Figure 4).

FIGURE 4. Once the contents are completely reduced, anatomy can be meticulously assessed and relation to relevant structures (such as nerves) can be well visualized. Careful interpretation of the course of the nerves seems imminent in preventing potential debilitating neuralgia by unintended nerve damage during port closure or mesh placement.

Step 5. The hernia port rarely exceeds 4 cm and can usually be closed well, primarily using a slowly resorbable 3/0 barbed suture. Care must be taken not to damage the nerves in close proximity to the hernia port (see Figure 5).

FIGURE 5. The hernia port rarely exceeds 4 cm and can usually be closed well, primarily using a slowly resorbable barbed suture. Care must be taken not to damage the nerves in close proximity to the hernia port.

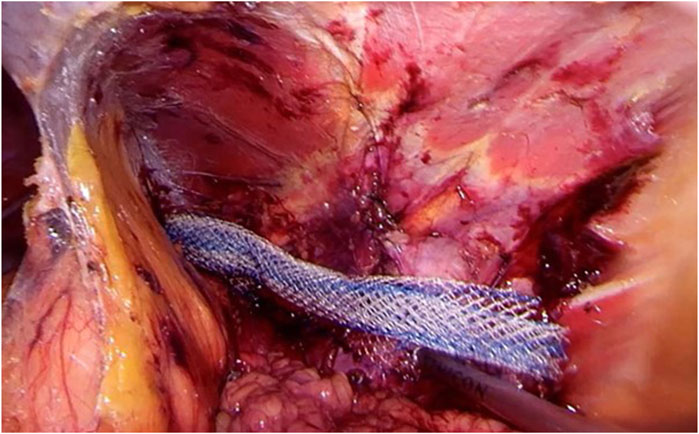

Step 6. A flat, microporous, and light-weighted mesh is inserted, offering 5 cm overlap over the closed port. There is no hard evidence to suggest the superiority of one manufacturer over another. The mesh has been rolled and secured with a stay suture before insertion in order to allow easier handling. The dorsal border is fixated to the quadratus lumborum muscle at 5 cm distance from the port site using absorbable or nonabsorbable tacks. Care should be taken not to place tacks in close proximity to the nerves (Figure 6).

FIGURE 6. A flat, macroporous, and light-weighted mesh is rolled up and fixated with a temporary suture. Then, the mesh is inserted and the posterior border is secured using absorbable tacks, offering 5 cm overlap over the closed port.

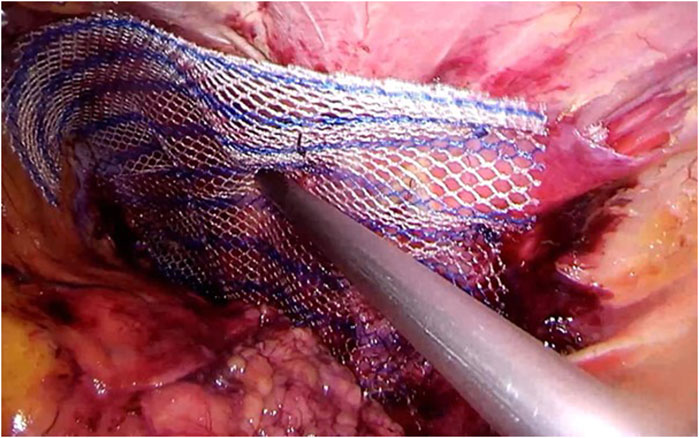

Step 7. The temporary stay suture is cut, and the mesh can be easily deployed and fixated using the same tacks to the serratus and anterior oblique muscles (Figure 7).

FIGURE 7. The temporary suture is cut, and the mesh can then be deployed and fixated using the same absorbable tacks to the serratus and anterior oblique muscles, offering the same 5 cm overlap.

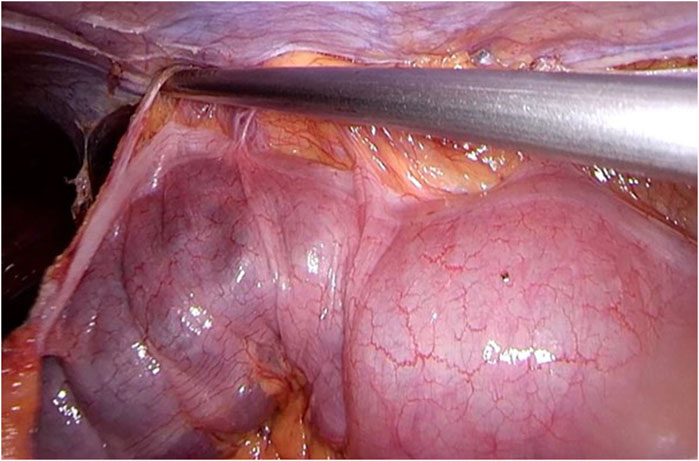

Step 8. The peritoneum and splenic flexure are repositioned and fixated, making sure the mesh is well covered with peritoneum to prevent intra-abdominal complications (see Figure 8). Desufflation, removal of trocars and closure of the wounds according to local protocol. The patient can be discharged the same day if postoperative pain is adequately treated using medication.

FIGURE 8. The peritoneum and splenic flexure are repositioned and fixated, making sure the mesh is well covered with peritoneum to prevent intra-abdominal complications. After desufflation, removal of trocars, and closure of the wounds, the operation comes to an end. The patient can be discharged the same day if postoperative pain is adequately treated using medication.

Results

In our combined limited experience of only six patients (in four different hospitals), the use of a TAPP approach has proven easy to master, safe, and effective. All our cases were performed without complications such as neuralgia or hematoma, and we have not seen a recurrence yet. However, follow-up since the last case is only 5 months and our numbers are too low for an accurate recurrence rate.

Discussion

Lumbar hernias are a rare entity and hard evidence on optimal diagnosis and treatment is lacking. Therefore, no one technique can convincingly be considered the gold standard. However, using the scarce literature available on this topic and adding information extrapolated from the literature on other hernias, a standardized, relatively safe, and easy strategy for surgical treatment might be proposed that can be performed by every adequately trained surgeon with significant expertise in hernia surgery.

Ethics Statement

The authors specifically state that the surgical procedure suggested in our manuscript should not be considered a novel or experimental treatment strategy, but should be considered a pragmatic chosen variant of various regularly used treatment modalities. Although large studies on the specific treatment of lumbar hernia do not exist, the majority of technical aspects advocated in our manuscript can be extrapolated from well designed and adequately powered studies on the optimal treatment of other but somewhat similar hernias. Therefore, ethics approval or specific consent procedures were not required for this study.

Author Contributions

All authors did have full control of all primary data and we agree to allow the journal to review this data if requested. All authors contributed to the study conception and design. The first draft of the manuscript was written by JH and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. We use an anatomical drawing, provided by SS, that has been published before by SS et al. in “Hernia” (see ref [19]).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. Goodman, EH, and Speese, J. Lumbar Hernia. Ann Surg (1916) 63:548–60. doi:10.1097/00000658-191605000-00008

2. Moreno-Egea, A, Baena, EG, Calle, MC, Martínez, JAT, and Albasini, JLA. Controversies in the Current Management of Lumbar Hernias. Arch Surg (2007) 142:82–8. doi:10.1001/archsurg.142.1.82

3. Esposita, TJ, and Fedorak, I. Traumatic Lumbar Hernia: Case Report and Literature Review. J Trauma (1996) 37:123–6.

4. Heniford, BT, Lannitti, DA, and Gagner, M. Laparoscopic Inferior and Superior Lumbar Hernia Repair. Arch Surg (1997) 132:1141–4. doi:10.1001/archsurg.1997.01430340095017

5. Pul, M, Pul, N, and Gürses, N. Congenital Lumbar (Grynfelt-Lesshaft) Hernia. Eur J Pediatr Surg (1991) 1:115–7. doi:10.1055/s-2008-1042471

6. Wakhlu, A, and Wakhlu, AK. Congenital Lumbar Hernia. Pediatr Surg Int (2000) 16:146–8. doi:10.1007/s003830050048

7. Sharma, A, Pandey, A, Rawat, J, Ahmed, I, Wakhlu, A, and Kureel, SN. Congenital Lumbar Hernia: 20 Years’ Single Centre Experience. J Paediatr Child Health (2012) 48:1001–3. doi:10.1111/j.1440-1754.2012.02581.x

8. Vagholkar, K, and Dastoor, K. Congenital Lumbar Hernia With Lumbocostovertebral Syndrome: A Case Report and Review of the Literature. Case Rep Pediatr (2013) 2013:532910. doi:10.1155/2013/532910

9. Tasis, N, Tsouknidas, I, Antonopoulou, MI, Acheimastos, V, and Manatakis, DK. Congenital Lumbar Herniae: A Systematic Review. Hernia (2022) 26:1419–25. doi:10.1007/s10029-021-02473-x

10. Selby, CD. Direct Abdominal Hernia of Traumatic Origin. Jamaa (1906) 47:1485. doi:10.1001/jama.1906.25210180061002c

11. Burt, BM, Afifi, HY, Wantz, GE, and Barie, PS. Traumatic Lumbar Hernia: Report of Cases and Comprehensive Review of the Literature. J Trauma (2004) 57:1361–70. doi:10.1097/01.ta.0000145084.25342.9d

12. Park, Y, Chung, M, and Lee, MA. Traumatic Lumbar Hernia: Clinical Features and Management. Ann Surg Treat Res (2018) 95:340–4. doi:10.4174/astr.2018.95.6.340

13. Munhoz, AM, Montag, E, Arruda, EG, Sturtz, G, and Gemperli, R. Management of Giant Inferior Triangle Lumbar Hernia (Petit's Triangle Hernia): A Rare Complication Following Delayed Breast Reconstruction With Extended Latissimus Dorsi Myocutaneous Flap. Int J Surg Case Rep (2014) 5:319–23. doi:10.1016/j.ijscr.2014.03.026

14. Rafols, M, Bergholz, D, Andreoni, A, Knickerbocker, C, Davies, J, and Grossman, RA. Bilateral Lumbar Hernias Following Spine Surgery: A Case Report and Laparoscopic Transabdominal Repair. Case Rep Surg (2020) 2020:8859106. doi:10.1155/2020/8859106

15. Loukas, M, Tubbs, RD, El-Sedfy, A, Jester, A, Polepalli, S, Kinsela, C, et al. The Clinical Anatomy of the Triangle of Petit. Hernia (2007) 11:441–4. doi:10.1007/s10029-007-0232-5

16. Loukas, M, El-Zammar, D, Shoja, MM, Tubbs, RS, Zhan, L, Protyniak, B, et al. The Clinical Anatomy of the Triangle of Grynfeltt. Hernia (2008) 12:227–31. doi:10.1007/s10029-008-0354-4

17. Stamatiou, D, Skandalakis, JE, Skandalakis, LJ, and Mirilas, P. Lumbar Hernia: Surgical Anatomy, Embryology, and Technique of Repair. Am Surg (2009) 75:202–7. doi:10.1177/000313480907500303

18. Suarez, S, and Hernandez, JD. Laparoscopic Repair of a Lumbar Hernia: Report of a Case and Extensive Review of the Literature. Surg Endosc (2013) 27:3421–9. doi:10.1007/s00464-013-2884-9

19. Steensel van, S, Bloemen, A, Hil van den, LCL, van den Bos, J, Kleinrensink, GJ, and Bouvy, ND. Pitfalls and Clinical Recommendations for the Primary Lumbar Hernia Based on a Systematic Review of the Literature. Hernia (2019) 23:107–17. doi:10.1007/s10029-018-1834-9

20. Light, HG. Hernia of the Inferior Lumbar Space: A Cause of Back Pain. Arch Surg (1983) 118:1077–80. doi:10.1001/archsurg.1983.01390090061014

21. Hsu, SD, Shen, KL, Liu, HD, Chen, TW, and Yu, JC. Lumbar Hernia: Clinical Analysis of Cases and Review of the Literature. Chir Gastroenterol (2008) 24:221–4. doi:10.1159/000151304

22. Lillie, GR, and Deppert, E. Inferior Lumbar Triangle Hernia as a Rarely Reported Cause of Low Back Pain: A Report of 4 Cases. J Chiropr Med (2010) 9:73–6. doi:10.1016/j.jcm.2010.02.001

23. Horovitz, IL, Schwarz, HA, and Dehan, A. A Lumbar Hernia Presenting as an Obstructing Lesion of the Colon. Dis Colon Rectum (1986) 29:742–4. doi:10.1007/BF02555323

24. Astarcioglu, H, Sokmen, S, Atila, K, and Karademir, S. Incarcerated Inferior Lumbar (Petit’s) Hernia. Hernia (2003) 7:158–60. doi:10.1007/s10029-003-0128-y

25. Zhou, X, Nve, JO, and Chen, G. Lumbar Hernia: Clinical Analysis of 11 Cases. Hernia (2004) 8:260–3. doi:10.1007/s10029-004-0230-9

26. Light, D, Gopinath, B, Banerjee, A, and Ratnasingham, K. Incarcerated Lumbar Hernia: A Rare Presentation. Ann R Coll Surg Engl (2010) 92:W13–W14. doi:10.1308/147870810X12659688851393

27. Fokou, M, Fotso, P, Ngowe Ngowe, M, Essomba, A, and Sosso, M. Strangulated or Incarcerated Spontaneous Lumbar Hernia as Exceptional Cause of Intestinal Obstruction: Case Report and Review of the Literature. Worl J Emerg Surg (2014) 16:44. doi:10.1186/1749-7922-9-44

28. Scheffler, M, Renard, J, Bucher, P, and Botsikas, D. Incarcerated Grynfeltt-Lesshaft Hernia. J Radiol Case Rep (2015) 9:9–13. doi:10.3941/jrcr.v9i4.2073

29. Guillem, P, Czarnecki, E, Duval, G, Bounoua, F, and Fontaine, C. Lumbar Hernia: Anatomical Route Assessed by Computed Tomography. Surg Radiol Anat SRA (2002) 24:53–6. doi:10.1007/s00276-002-0003-z

30. Salameh, JR, and Salloum, EJ. Lumbar Incisional Hernias: Diagnostic and Management Dilemma. JSLS (2004) 8:391–4.

31. Martin, J, Mellado, JM, Solanas, S, Yanguas, N, Salceda, J, and Cozcolluela, MR. MDCT of Abdominal Wall Lumbar Hernias: Anatomical Review, Pathologic Findings and Differential Diagnosis. Surg Radiol Anat (2012) 34:455–63. doi:10.1007/s00276-012-0937-8

32. Ahmed, ST, Ranjan, R, Saha, SB, and Singh, B. Lumbar Hernia: A Diagnostic Dilemma. BMJ Case Rep (2014) 2014:2013202085. doi:10.1136/bcr-2013-202085

33. Steerman, SN, and Steerman, PH. Scoliotic Lumbar Hernia as a Cause of Colonic Obstruction. J Am Coll Surg (2004) 199:162. doi:10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2004.01.038

34. Teo, KA, Burns, E, Garcea, G, Abela, JE, and McKay, CJ. Incarcerated Small Bowel Within a Spontaneous Lumbar Hernia. Hernia (2010) 14:539–41. doi:10.1007/s10029-009-0581-3

35. Blair, LC, Cox, TC, Huntington, CR, Ross, SW, Kneisl, JS, Augenstein, VA, et al. Bone Anchor Fixation in Abdominal Wall Reconstruction: A Useful Adjunct in Suprapubic and Para-Iliac Hernia Repair. Am Surg (2015) 81:693–7. doi:10.1177/000313481508100718

36. Cavallaro, G, Sadighi, A, Micelli, M, Burza, A, Carbone, G, and Cavallaro, A. Primary Lumbar Hernia Repair: The Open Approach. Eur Surg Res (2007) 39:88–92. doi:10.1159/000099155

37. Vagholkar, K, and Vagholkar, S. Open Approach to Primary Lumbar Hernia Repair: A Lucid Option. Case Rep Chir (2017) 2017:5839491. doi:10.1155/2017/5839491

38. Dowd, CN. Congenital Lumbar Hernia, at the Triangle of Petit. Ann Surg (1907) 45:245–8. doi:10.1097/00000658-190702000-00007

39. Legbo, JN, and Legbo, JF. Abdominal Wall Reconstruction Using De-Epithelialized Dermal Flap: A New Technique. J Surg Techn Case Rep (2010) 2:3–7. doi:10.4103/2006-8808.63707

40. Arca, MJ, Heniford, BT, Pokorny, M, Wilson, MA, Mayes, J, and Gagner, M. Laparoscopic Repair of Lumbar Hernias. J Am Coll Surg (1998) 187:147–52. doi:10.1016/s1072-7515(98)00124-0

42. Bigolon, AV, Rodrigues, AP, Trevisan, CG, Geist, AB, Coral, RV, Rinaldi, N, et al. Petit Lumbar Hernia – A Double Layer Technique for Tensior-Free Repair. Int Surg (2014) 99:556–9.

43. Brill, JB, and Turner, PL. Long-Term Outcomes With Transfascial Sutures Versus Tacks in Laparoscopic Ventral Hernia Repair: A Review. Am Surg (2011) 77:458–65. doi:10.1177/000313481107700423

44. Carbonell, AM, Kercher, KW, Sigmon, L, Matthews, BD, Kneisl, JS, Heniford, BT, et al. A Novel Technique of Lumbar Hernia Repair Using Bone Anchor Fixation. Hernia (2005) 9:22–5. doi:10.1007/s10029-004-0276-8

45. Bickel, A, Haj, M, and Eitan, A. Laparoscopic Management of Lumbar Hernia. Surg Endosc (1997) 11:1129–30. doi:10.1007/s004649900547

46. Moreno-Egea, A, Torralba-Martinez, JA, Moralez, JA, Fernández, T, Girela, E, and Aguayo-Albasini, JL. Open vs Laparoscopic Repair of Secondary Lumbar Hernias: A Prospective Nonrandomized Study. Surg Endosc (2005) 19:184–7. doi:10.1007/s00464-004-9067-7

47. Ipek, T, Eyuboglu, E, and Aydingoz, O. Laparoscopic Management of Inferior Lumbar Hernia (Petit Triangle Hernia). Hernia (2005) 9:184–7. doi:10.1007/s10029-004-0269-7

48. Moreno-Egea, A, and Carillo-Alcaraz, A. Management of Non-Midline Incisional Hernia by the Laparoscopic Approach: Results of a Long-Term Follow-Up Prospective Study. Surg Endosc (2012) 26:1069–78. doi:10.1007/s00464-011-2001-x

49. Henriksen, NA, Montgomery, A, Kaufmann, R, Berrevoet, F, East, B, Fischer, J, et al. Guidelines for Treatment of Umbilical and Epigastric Hernias From the European Hernia Society and Americas Hernia Society. BJS (2020) 107:171–90. doi:10.1002/bjs.11489

50. Mathes, T, Walgenbach, M, and Siegel, R. Suture versus Mesh Repair in Primary and Incisional Ventral Hernias: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. World J Surg (2016) 40:826–35. doi:10.1007/s00268-015-3311-2

51. Clapp, ML, Hicks, SC, Awad, SS, and Liang, MK. Trans-Cutaneous Closure of Central Defects (TCCD) in Laparoscopic Ventral Hernia Repairs (LVHR). World J Surg (2013) 37:42–51. doi:10.1007/s00268-012-1810-y

52. Nguyen, DH, Nguyen, MT, Askenasy, EP, Kao, LS, and Liang, MK. Primary Fascial Closure With Laparoscopic Ventral Hernia Repair: Systematic Review. World J Surg (2014) 38:3097–104. doi:10.1007/s00268-014-2722-9

53. Wang, T, Tang, R, Meng, X, Zhang, Y, Huang, L, Zhang, A, et al. Comparative Review of Outcomes: Single-Incision Laparoscopic Total Extraperitoneal Sub-Lay (SIL-TES) Mesh Repair Versus Laparoscopic Intraperitoneal Onlay Mesh (IPOM) Repair for Ventral Hernia. Updates Surg (2022) 74:1117–27. doi:10.1007/s13304-022-01288-4

54. Maatouk, M, Khbir, GH, Mabrouk, A, Rezgui, B, Dhaou, AB, Daldoul, S, et al. Can Ventral TAPP Achieve Favorable Outcomes in Minimal Invasive Ventral Hernia Repair? A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Hernia (2023). 27(4) 729–39. doi:10.1007/s10029-022-02709-4

55. Patel, PP, Love, MW, Ewing, JA, Warren, JA, Cobb, WS, and Carbonell, AM. Risks of Subsequent Abdominal Operations After Laparoscopic Ventral Hernia Repair. Surg Endosc (2017) 31:823–8. doi:10.1007/s00464-016-5038-z

56. Yeow, M, Wijerathne, S, and Lomanto, D. Intraperitoneal Versus Extraperitoneal Mesh in Minimally Invasive Ventral Hernia Repair: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Hernia (2022) 26:533–41. doi:10.1007/s10029-021-02530-5

57. Leblanc, K. Proper Mesh Overlap Is a Key Determinant in Hernia Recurrence Following Laparoscopic Ventral and Incisional Hernia Repair. Hernia (2016) 20:85–99. doi:10.1007/s10029-015-1399-9

58. Tulloh, B, and de Beaux, A. Defects and Donuts: The Importance of the Mesh: Defect Area Ratio. Hernia (2016) 20:893–5. doi:10.1007/s10029-016-1524-4

59. Meinke, AK. Totally Extraperitoneal Laparoendoscopic Repair of Lumbar Hernia. Surg Endosc (2003) 17:734–7. doi:10.1007/s00464-002-8557-8

60. Habib, E. Retroperitoneoscopic Tension-Free Repair of Lumbar Hernia. Hernia (2003) 7:150–2. doi:10.1007/s10029-002-0109-6

61. Shah, NS, Fullwood, C, Siriwardena, AK, and Sheen, AJ. Mesh Fixation at Laparoscopic Inguinal Hernia Repair: A Meta-Analysis Comparing Tissue Glue and Tack Fixation. World J Surg (2014) 38:2558–70. doi:10.1007/s00268-014-2547-6

62. Cohen, RV, Alvarez, G, Roll, S, Garcia, ME, Kawahara, N, Schiavon, CA, et al. Transabdominal of Totally Extraperitoneal Laparoscopic Hernia Repair? Surg Laparosc Endosc (1998) 8:264–8.

63. Liebl, BJ, Jäger, C, Kraft, B, Kraft, K, Schwarz, J, Ulrich, M, et al. Laparoscopic Hernia Repair – TAPP Or/and TEP? Langenbecks Arch Surg (2005) 390:77–82. doi:10.1007/s00423-004-0532-5

64. Shekarriz, B, Graziottin, TM, Gholami, S, Lu, HF, Yamada, H, Duh, QY, et al. Transperitoneal Preperitoneal Laparoscopic Lumbar Incisional Herniorrhaphy. J Urol (2001) 166:1267–9. doi:10.1097/00005392-200110000-00011

65. Sharma, A, Panse, A, Khullar, R, Soni, V, Baijal, M, and Chowbey, PK. Laparoscopic Transabdominal Extraperitoneal Repair of Lumbar Hernia. J Minim Access Surg (2005) 1:70–3. doi:10.4103/0972-9941.16530

66. Sun, J, Chen, X, Li, J, Zhang, Y, Dong, F, and Zheng, M. Implementation of the Trans-Abdominal Partial Extraperitoneal (TAPE) Technique in Laparoscopic Lumbar Hernia Repair. BMC Surg (2015) 15:118. doi:10.1186/s12893-015-0104-3

67. Stirler, VMA, Nallayici, EG, de Haas, RJ, Raymakers, JTFJ, and Rakic, S. Postoperative Pain After Laparoscopic Repair of Primary Umbilical Hernia: Titanium Tacks Versus Absorbable Tacks: A Prospective Comparative Cohort Analysis of 80 Patients With a Long-Term Follow-Up. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech (2017) 27:424–7. doi:10.1097/SLE.0000000000000467

68. Harslof, S, Krum-Moller, P, Sommer, T, Zinther, N, Wara, P, and Friis-Andersen, H. Effect of Fixation Devices on Postoperative Pain After Laparoscopic Ventral Hernia Repair: A Randomized Clinical Trial of Permanent Tacks, Absorbable Tacks, and Synthetic Glue. Langenbecks Arch Surg (2018) 403:529–37. doi:10.1007/s00423-018-1676-z

Keywords: lumbar hernia, treatment, surgery, abdominal wall, intestinal obstruction

Citation: Heemskerk J, Leijtens JWA and van Steensel S (2023) Primary Lumbar Hernia, Review and Proposals for a Standardized Treatment. J. Abdom. Wall Surg. 2:11754. doi: 10.3389/jaws.2023.11754

Received: 29 June 2023; Accepted: 15 November 2023;

Published: 06 December 2023.

Copyright © 2023 Heemskerk, Leijtens and van Steensel. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Jeroen Heemskerk, ai5oZWVtc2tlcmtAbHpyLm5s, orcid.org/0000-0001-9373-9725

Jeroen Heemskerk

Jeroen Heemskerk Jeroen Willem Alfons Leijtens1

Jeroen Willem Alfons Leijtens1 Sebastiaan van Steensel

Sebastiaan van Steensel