- 1NHS England, London, United Kingdom

- 2School of Medical and Health Sciences, Bangor University, Bangor, United Kingdom

- 3Donation and Transplant Coordination Section, Hospital Clinic, Barcelona, Spain

- 4Surgical Department, University of Barcelona, Barcelona, Spain

- 5Donation and Transplantation Institute Foundation, Barcelona, Spain

- 6NHS Blood and Transplant, Watford, United Kingdom

- 7Policy Innovation and Evaluation Research Unit, London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, London, United Kingdom

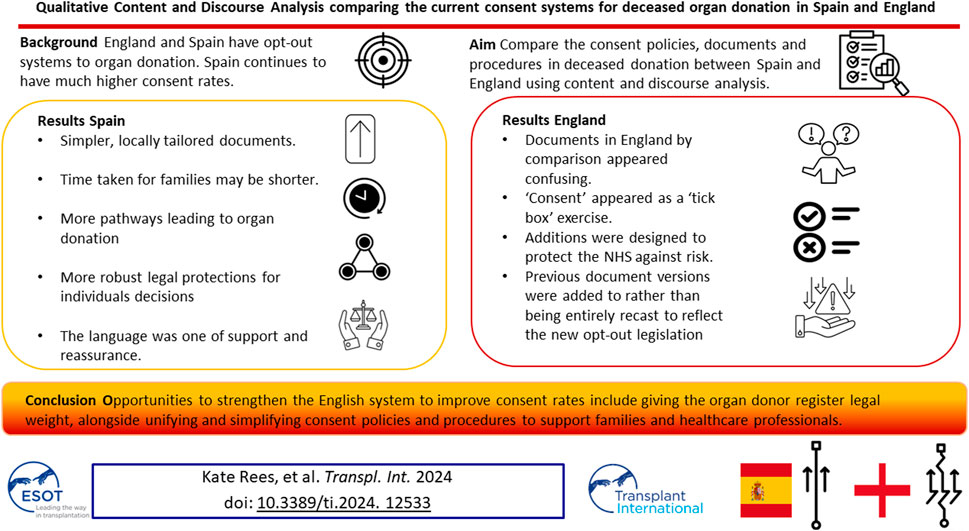

England switched to an opt-out system of consent in 2020 aiming to increase the number of organs available. Spain also operates an opt-out system yet has almost twice the organ donations per million population compared with England. We aimed to identify both differences and similarities in the consent policies, documents and procedures in deceased donation between the two countries using comparative qualitative content and discourse analysis. Spain had simpler, locally tailored documents, the time taken for families to review and process information may be shorter, there were more pathways leading to organ donation in Spain, and more robust legal protections for the decisions individuals made in life. The language in the Spanish documents was one of support and reassurance. Documents in England by comparison appeared confusing, since additions were designed to protect the NHS against risk and made to previous document versions to reflect the law change rather than being entirely recast. If England’s ambition is to achieve consent rates similar to Spain this analysis has highlighted opportunities that could strengthen the English system-by giving individuals’ decisions recorded on the organ donor register legal weight, alongside unifying and simplifying consent policies and procedures to support families and healthcare professionals.

Introduction

Since England switched to an opt-out consent system in May 2020, with the aim of making more organs available for transplant through the introduction of deemed consent, consent rates for deceased organ donation have not increased [1]. Despite high ambitions [2] England still appears to be falling short of the number of organs available achieved by Spain which has consistently had much higher organ donation rates (46.7 per million population in 2022) despite having a similar legal framework for deceased organ donation consent [3].

Presumed consent (sometimes referred to as deemed consent) means that a person is considered to have no objection to donating their organs after death unless they have registered or informed someone close to them that they do not wish to do so. There have been many studies that have concluded that presumed consent alone does not explain the fluctuation in donation rates between countries [4]. Legislation, public knowledge and awareness of organ donation, donor availability and characteristics, religious beliefs, transplant service infrastructure and healthcare system capacity (e.g., in intensive care), all play a part in making more organs available for transplant, but their relative importance is unclear [5–8].

England implemented their opt-out system to increase the consent rate for deceased organ donation, the assumption being that more organs would become available for transplant. However the opt-out legislation was nested within the existing opt-in system, and despite the addition of the new deemed consent pathway, the failure to secure consent for deceased organ donation retrieval from those involved in end-of-life discussions is still widely regarded as the single most important obstacle to making more organs available for transplant in England [9].

The purpose of this analysis was to identify differences and similarities in consent policies and associated documents between England and Spain and to consider whether there are opportunities to further increase consent rates for deceased organ donation and improve current practice in England.

Overall Context and Scope

This analysis was undertaken as part of a broader evaluation of the impact of opt-out in England on the organ donation system [10]. During the study it became clear that the processes involved in consent, in particular were lengthy, excessive and negatively impacted families in England [11]. Specialist staff involved in consent also felt the process to be excessive and burdensome [12]. The research team was aware of extensive research into gold standards in terms of pathways to organ donation, i.e., what should happen and by whom to achieve the desired outcomes (the so-called Spanish model) [13] but was unable to find examples (or research) of the consent documents used in practice in countries with opt-out systems, which are considered leaders in organ donation. We felt that as the main study was specifically commissioned to examine a policy that (in theory) shifts from a model of informed consent to a model of presumed consent it would be a worthwhile and interesting analysis to look more closely at the consent documents and associated policies and guidelines of the world’s leading country with an opt-out system and compare them.

Materials and Methods

Research Question

What are the differences in roles, processes, consent forms and practices between the Spanish and English systems of organ donation and how do any identified differences begin to explain the higher consent rates in Spain?

Data Collection

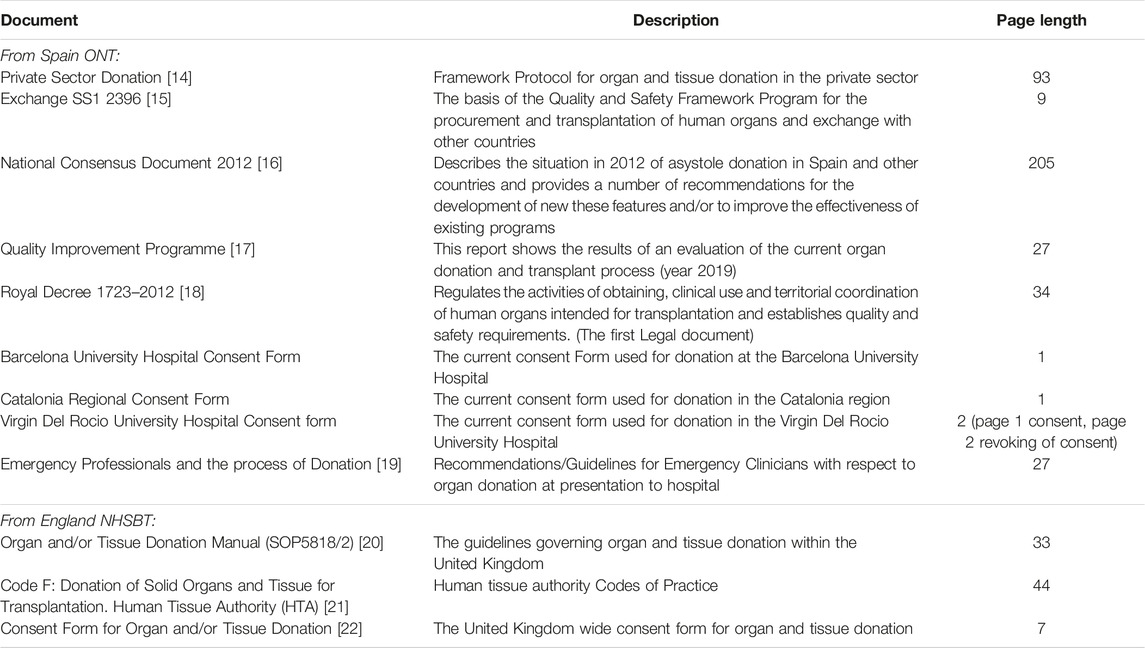

We identified and obtained key policy and procedure documents and consent forms from the websites of the “Organizacion Nacional de Transplantes” (ONT) in Spain and NHS Blood and Transplant (NHSBT) in England. Documents published in Spanish were translated into English for analysis using the “TransPerfect” computer software. Table 1 lists the documents included in the analysis [14–22]. The documents were read, reread, compared and coded.

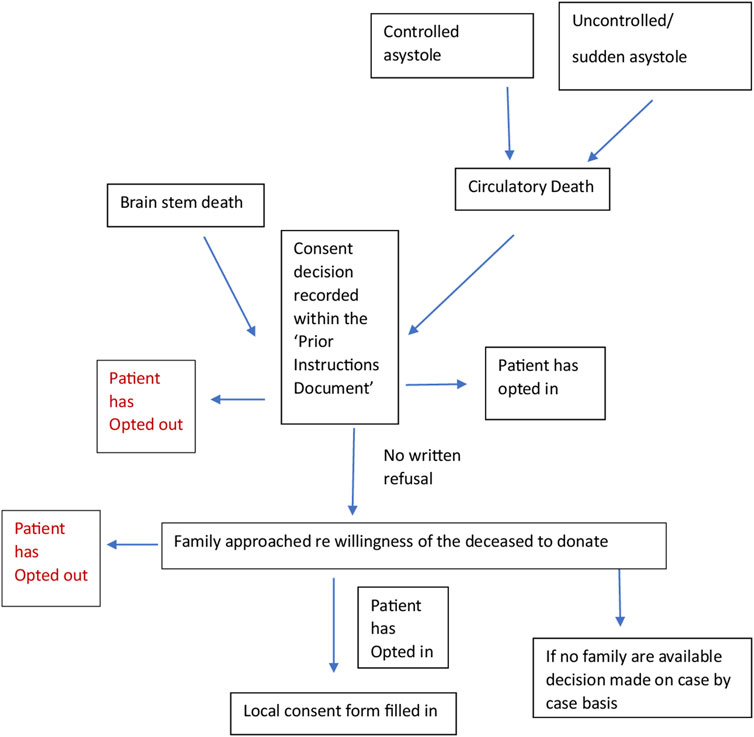

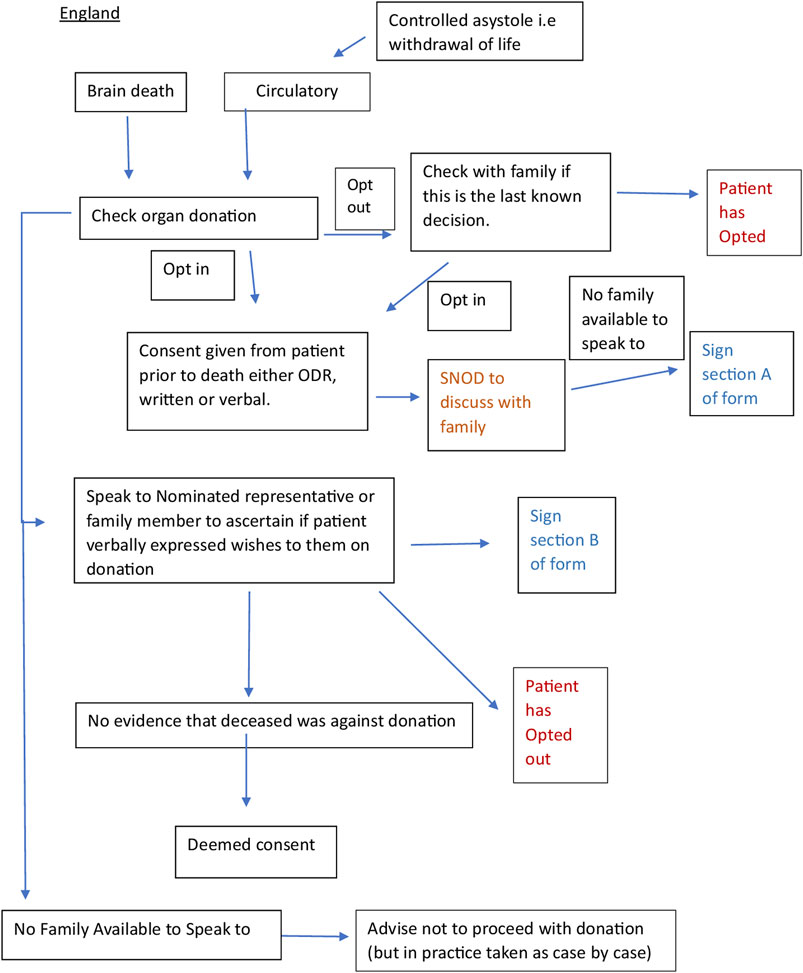

We worked with a Spanish intensive care doctor (co-author) via email and two online team sessions to clarify the correct interpretation of the documents and the donation system. This enabled us to verify that the current practice was in line with the written protocols. We engaged stakeholders through meetings with academics and cliniciansorganized by the European Society for Organ Transplantation (ESOT) to help establish the context of the English and Spanish organ donation systems within which the documents for analysis were produced. We consulted with a United Kingdom senior nurse (co-author) involved in the English NHSBT education program and United Kingdom legislation. A summary flowchart of the Spanish and English organ donation structures and processes was made for comparison (Figures 1, 2).

Figure 1. Flow chart of the English and Spanish process constructed from documents (20–22) and stakeholder engagement.

These processes helped to build a better understanding of broad cultural factors, such as religious beliefs, ethnic diversity, family dynamics, the reaction of families to the system and whether they had ever challenged the law, and how these might be underpinning any differences observed in the documents analyzed in detail.

Data Analysis

Qualitative content analysis was used to code, analyze, compare and interpret the textual data and diagrams in the included documents to gain insight into the meaning and context of the policy, and the links between content, process and outcome [23].

Coding involved assigning attributes to words, sentences, or paragraphs to compare and contrast content, process and meaning. Consent forms were compared for structure, content, and length [24].

Principles of critical discourse analysis were used to make additional interpretations of the text, complemented by engagement with experts in the Spanish and English systems. This was done to systematically explore the often-opaque relationships between what is written (i.e., policies, guidelines) and what happens in practice, with multiple stakeholders, many with different objectives. This process helped to examine, for example, who or what the subjects and objects are in the respective structures, discourses and processes, and how and why the two systems manage to generate and maintain different forms of language (rhetoric) [25]. The flowcharts constructed (Figures 1, 2) helped to show where objects in relation to consent such as the Organ Donor Register, the roles of the staff, e.g., clinicians, transplant coordinators, nursing staff and the role and hierarchy of the family, etc. fit together in a complex system. The rhetorical analysis specifically searched for opportunities to give or decline consent within the process. This enabled us to understand more about the mechanisms underpinning the Spanish consent pathway, and thus extrapolate findings that may be applicable, with adaptation, to England [26].

Author Reflexivity

Co-authors LM and JN were already working with colleagues in the English system and were connected via multiple professional networks to clinical and academic colleagues in Spain. Once the lead investigators had a good understanding of the two systems, we had further discussions with the Spanish consultant and Senior United Kingdom nurse co-authors to validate the interpretation of the two systems. We presented this work at several multi-disciplinary meetings and events including the Deconstructing Donation Special Interest Group for additional critique and insight. We adapted the recommendations for rigor, transparency, evidence, and representation to present the results [27].

Results

Box 1 provides a comparison of some key performance indicators in England and Spain in the year 2022.

Box 1 Comparison of key performance indicators between Spain and England 2022.

A direct comparison of the systems, processes, and cultural and linguistic styles between Spain and England in relation to consent for deceased organ donation is described below. Table 2 highlights similarities and differences within the systems with specific reference to consent (Table 2). The mechanisms that may or may not be a factor in achieving the desired outcomes in relation to consent are further unpacked and described in Table 3.

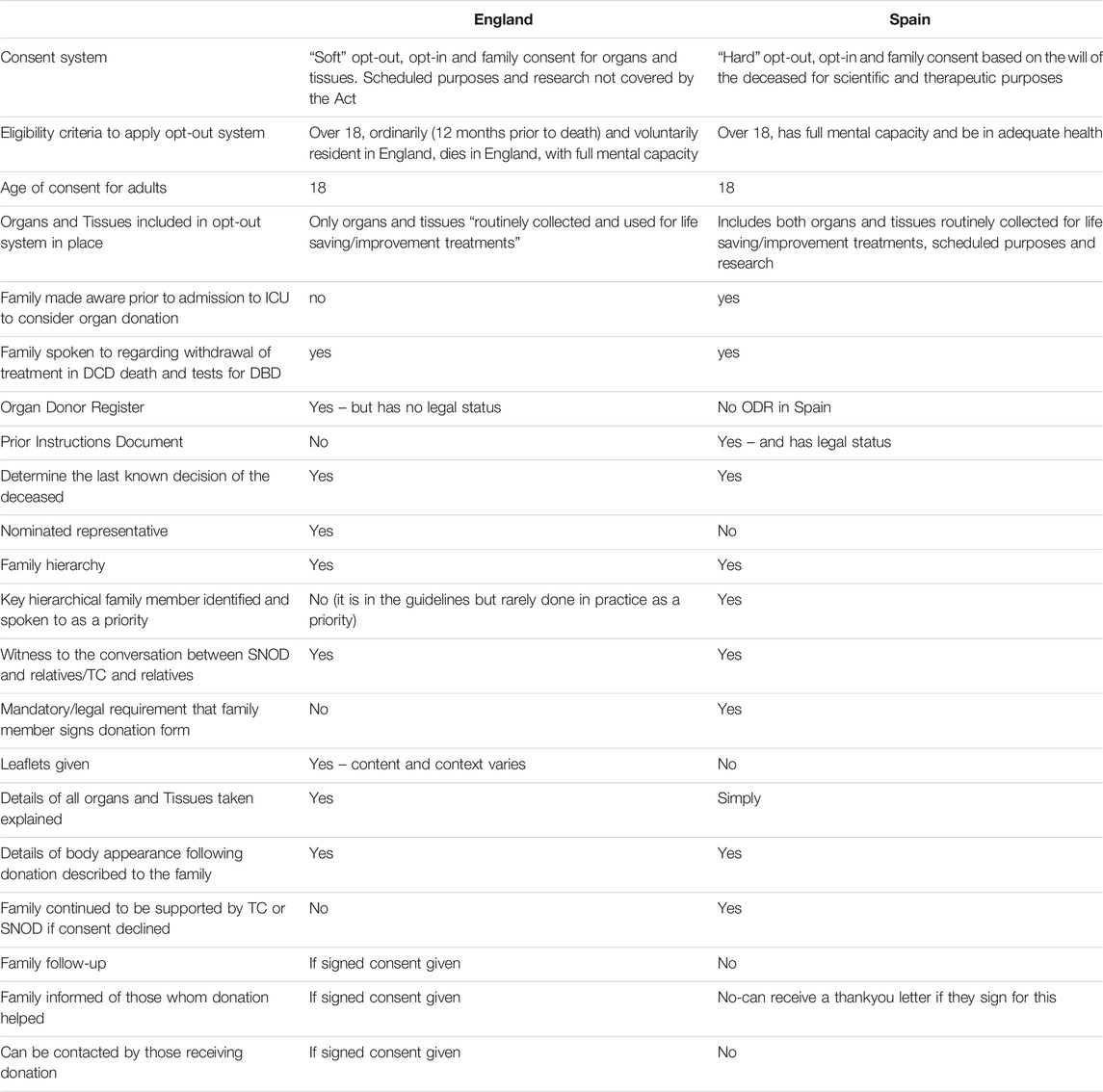

Table 2. Similarities and differences within the Spain and England systems with specific reference to consent.

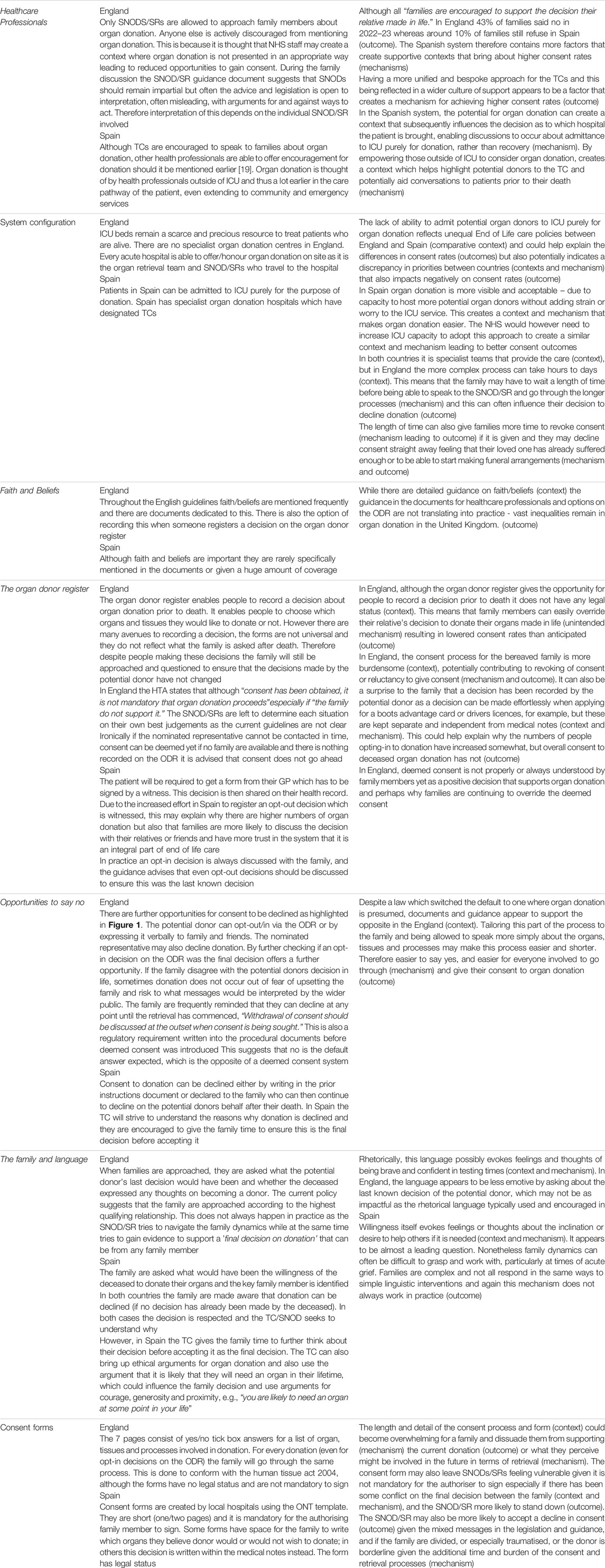

Table 3. Mechanisms which may be a factor in bringing about the desired outcomes, or not, in relation to consent.

Overall System

England has a diverse population with deep-rooted Christian traditions and multi-faith communities. England switched to an opt-out system of consent to deceased organ donation in May 2020. The organ donation system is run by the NHSBT, which is publicly funded and not privately available. Deceased organ donation is considered for those who die from brain stem or controlled circulatory death. Donation is therefore only possible for those who are admitted to an intensive care unit (ICU), but ICU admission is for treatment and prognostic purposes, not for organ donation [28–30].

England has an intensive care bed capacity of approximately 6.6 per 100,000 people [31]. Organ donation is possible in every acute NHS hospital. When the patient is identified as a potential donor the clinical team caring for the patient will refer the patient via a national referral number. The regional NHSBT team will assess the patient and mobilize a Specialist Requester (SR) or Specialist Nurse in Organ Donation (SNOD) – depending on who is available. After checking the national Organ Donor Register (ODR), the SNOD/SR will visit the unit and approach the family about donation – this is a nurse-led process and care pathway. The ODR has various options (e.g., opt-in, opt-out, nominate a representative and the ability to specify a small number of organs/tissues that people do or do not want to donate after death) but it has no legal status and family members have the ability to override it in practice and even register a decision on behalf of their loved one. Hospitals are reimbursed a small sum for facilitating organ donation, (approximately 1,000 pounds per donor) but this figure has not increased substantially over time and complex and bureaucratic finance systems often make it difficult to spend and save money to promote organ donation.

Spain is a predominantly Catholic country and has had an organ donation system for 44 years [32]. The organ donation system is overseen by the ONT. It is possible to be an organ donor while being treated privately, by being transferred to the public health system for donation purposes only. In addition to the pathways in England, deceased organ donation can be obtained from sudden unexpected circulatory deaths and those undergoing euthanasia. Spain has an intensive care bed capacity of approximately 9.7 beds per 100,000 people [33]. In Spain, patients admitted to the Emergency Department with catastrophic brain or cardiac damage where treatment is considered futile, can be intubated, and admitted to the ICU for the purpose of organ donation [34]. Also, those who are suspected of developing brain death or have already been declared brain dead in private institutions or the Emergency Department, can be admitted to the ICU solely for the purpose of organ donation, unlike in England.

Spain has dedicated hospitals where deceased organ retrieval can occur, with designated transplant coordinators (TC) in each of these hospitals (approximately 70% being physicians and 30% nurses). Often in hospitals with no TC, there will be proactive ICU staff who can identify donors. They can request support from a dedicated hospital which will usually send a TC to aid in speaking with the family. Any healthcare professional can contact the TC regarding a potential donor. Once alerted to a potential donor the TC will visit the potential case, review the medical records, and determine whether or not there is a “prior instructions document.” This document has legal status.

System Processes Concerning Deceased Organ Donation Consent

In England “the individual leading the family approach for organ donation must be suitably trained and qualified with sufficient knowledge and skills to sensitively answer any questions and have the time to support the family,” [21, pg 9]. In practice, this is always the SNOD/SR, anybody outside of this role is actively discouraged from discussing organ donation [12].

As illustrated in Figure 1, the English system has many pathways to consent. If the deceased opted for organ donation during their lifetime, this is discussed with the family to ensure that this was the last known decision. If the deceased had opted out of the ODR “providing work load allows, the SNOD should also discuss with the family if this was the last known decision.” [SIC] [20, pg 11]. If this is not possible due to workload, the SNOD/SR will “coach the clinician in the discussion to have with the family and agree actions.” If the clinician feels unable to do this, the family will have to wait for the arrival of the SNOD/SR. In practice, detailed discussions with the family when the deceased has opted out rarely happen due to limited resources and concerns about NHSBT being seen as pushing for organ donation when the deceased has opted out.

Another pathway, although rare, is the “nominated representative,” where a person nominates someone else to make a decision on their behalf before they die. “If despite all reasonable efforts the nominated representative cannot be contacted in time or to make a decision, then consent may be deemed.” [SIC] [21, pg 19] Nonetheless, the donation can only take place after the family has also been consulted.

Only after the SNOD/SR has established that none of the above pathways apply, can they check whether consent can be assumed. If the family cannot agree, despite being given time and further information, then “the hierarchy of consent, i.e., highest qualifying relationship,” applies but the final decision to proceed lies with the [SNOD/SR].’ [SIC] In reality, it is the family member with the strongest voice (either for or against donation) whose wishes are followed [11, 35]. In addition, the SNOD/SR cannot proceed with the donation unless they have the full support (and permission) of the treating clinical team(s). If the family cannot be contacted and there is no prior expression of a decision, then although “consent could be deemed it is advised that donation must not proceed.’”[SIC] [21, pg 17].

To override a decision, families need only provide a “level of information that would lead a reasonable person to conclude that they [i.e., the deceased] did not want to be a donor.” [21, pg 24]. This may be verbal or written. Any evidence from any family member at this point can be taken into account. [21, pg 18] The SNOD/SR will make a judgment about the reliability of the information and whether it is right for the donation to proceed. “Sometimes clinical staff will reach the judgement that although there is a legal basis to proceed with the donation, the human considerations involved mean that it should not go ahead. While the presence of appropriate consent permits organ and tissue donation to take place, it does not mandate that it must….(and) where the risks to public confidence might outweigh the benefits of donation proceeding, donation should not proceed even though the law permits it.” [SIC] [21, pg 7].

In Spain, there is no organ donor register but a prior instructions document is available from the patient’s GP. Patients can register their consent or refusal to be an organ donor in the document which will be made available in the local Advance Directives Registry. Their families will be approached and informed of the recorded decision. If a “No” to the donation has been recorded, the family will still be asked if there has been any recent change to this decision. However, there would have to be substantial evidence to overturn this notion since the prior instructions document has legal value and is signed by a witness.

It is recommended that the healthcare professional who mentions organ donation be different from the professional who has discussed the likelihood of the patient dying to avoid a conflict of interest for the TC who may also have a role as an intensivist, etc. It is mandatory in some hospitals that the TC be contacted before withdrawal of treatment in the ICU, a condition introduced by some hospital medical directors.

The Consent Forms

The English consent form is seven pages long, with all organs, tissues and retrieval processes listed as yes/no checkboxes, including options for additional information. The family will need to answer “Yes” or “No” to everything irrespective of what the deceased had registered about what organs they wanted to donate while they were alive and this will include organ donation for research (not just therapeutic purposes). The family will be made aware that the decision can be revoked until “knife to skin.” [20, pg 24]. The family members “are encouraged to sign the consent form” although there is no legal obligation to do so. The process may take hours to days. The SNOD/SR will document the conversation in the patient’s notes and on the NHSBT’s national digital system, also verified by a witness. If the family were to override the decision or revoke consent this will be respected and the reasons would be acknowledged and recorded by the SNOD/SR.

Each Spanish region has its own form based on examples from the ONT protocols. Often they are a single page requesting the name and relationship of the relative and the date. Some do have a free text space for the family to write what organs or tissues they believe the deceased would not have wished to donate. In other cases, these wishes are documented in the medical notes instead. Once a decision is reached after discussion with the family, it is mandatory that the consent form be signed by the dissenting family member(s).

Approach and Language for Consent

In England, when families are approached, they are asked, “what the potential donor’s last decision would have been and whether the deceased expressed any thoughts on becoming a donor” [SIC]. The guidelines suggest that SNODs/SRs should establish who is the next of kin (in accordance with the established highest qualifying relationship guidance) and approach that relative to organ donation. Although the opportunity to help others is often mentioned, the overall guidelines suggest that the SNOD/SR should remain impartial [21].

In Spain, if there is no recorded decision made while alive, the family is generally asked: “what would have been the willingness of the deceased to donate their organs to help other people?” [SIC] [16, pg 197]. “If the family are in doubt, the TC can assist in decision-making, reinforcing positive verbalisations to donation and courage in those moments, and conveying ideas of generosity and proximity and enquiring whether the deceased gave to charity or donated blood during their lifetime, etc.” [SIC] [16, pg 126].

In the case of large families, the TC seeks to speak to the “key family” member. The key family member is identified through discussion with the family and the knowledge of the staff caring for the patient. Should a family be divided over the issue of donation, the TC will not proceed. If there is no family present, the TC “strive(s) through links with social services and the police to find a family member”[16, pg 120] but may still consider organ donation if no family can be found.

Should the family decline the donation, “it is important to make it clear that the decision is respected and understood but that, however, it is advisable to think about the matter more slowly without the presence of a TC.”[16, pg 126] The TC also explores the reasoning behind the refusal and corrects misunderstandings. The TC may approach the family as often as necessary.

During the consent process, the family is usually asked which organs they believe the deceased would not want to donate. The conversation aims to combine “speed and effectiveness in communicating with families, with respect for ethical principles and transparency that must preside over the process.” [SIC] [16, pg 116] On average, the process of gaining consent takes 30 min.

Discussion

This is the first detailed documentary comparison between the Spanish and English opt-out systems of consent to organ donation. The biggest differences observed were that the Spanish system was less complex in terms of consent, evidently pro-donation with a willingness to take some risks, likely to take less time, better resourced, with better access to ICU beds and a more locally tailored opt-out system with some legal protection for the potential organ donor’s life choices. England in contrast has a more complex centralized system with risk-adverse protocols, an itemized approach to consent, implemented in a country where there are fewer ICU beds, and no legal protection for the potential organ donor.

The Spanish system covers both public and private hospitals and has dedicated resources for organ donation, such as stand-alone centers and in-hospital beds. In England, for deceased organ donation, the NHSBT only covers NHS hospitals so some potential donors in the private sector are lost. There are no dedicated resources in England organ donation takes place when the system has the capacity to manage it which can potentially lead to frustration and disengagement of non-specialist staff. Euthanasia and organ donation are legal in Spain (illegal in England) and although the pathway is relatively recent it has created an additional platform to embed organ donation as a routine end-of-life process–the initial requests for this pathway have come from people who had requested euthanasia and not in the originaleuthanasia protocols. Potential organ donors with neurodegenerative conditions requesting euthanasia also tend to be younger without underlying co-morbidities and a single donor could potentially decide to donate all of their organs and tissues to help others, again increasing the visibility of organ donation in the system.

Families are as involved in decision-making in Spain as they are in England, but the consent process is shorter in Spain. The language used with family members and staff was also observed to be different in tone and meaning. The English system focuses on establishing the “last known decision of the deceased”whereas the Spanish system aims to establish “the will of the potential organ donor to donate their organs as well as the will to help others.” In England, current guidelines and codes of conduct reflect the human tissue authority’s position on consent to organ and tissue retrieval. This appears to be more in line with the old “opt-in” system and thus encourages unnecessary risk aversion which is contrary to the spirit of the opt-out legislation and appears confusing and neutral.

Organ donation appears to be more embedded within the Spanish healthcare system as an integral part of end-of-life care, with many healthcare professionals being aware of it and being encouraged to be involved with it. As such, it may be more likely to be discussed by families as there may be a healthcare worker in the family or someone they know who has been through the process before.

The legally binding prior instructions document is also available from the GP or local hospital and is signed with a witness present. Therefore, the witness, i.e., an accompanying family member is likely to be able to verify the document. Once completed, it is part of the person’s local medical record, meaning that there is a more complex process if family members want to challenge their loved one’s organ donation decision in life. There is a significant risk to donor decisions in England as anybody can go onto the ODR and register - SNODs/SRs continue to find cases where the opt-out decision was registered at a time when the person was being ventilated in the ICU [9].

The structure of the hospitals - i.e., that specific hospitals manage deceased organ donation, that patients can be admitted to the ICU purely for the need to ventilate organs and drug infusion in preparation for donation - is also very different from England. Matching the Spanish approach would undoubtedly cost the NHS more at the expense of another area of the health service. However, Spain states that “the social value of organ donation justifies staff efforts and the economic cost involved” [SIC] [16, pg 195], indicating an overall difference in priority in terms of deceased organ donation between the two countries.

In addition to the marked differences in the provision of ICU beds required for organ donation to proceed, in 2019, Spain had 3 hospital beds per 1,000 people whereas England had 2.5 beds per 1,000 people. In 2019, Spain had a bed occupancy rate of 76%, whereas in England the same rate was 92% for general and acute overnight beds [33]. Given the relentless pressure on NHS staff to continuously manage such a high bed occupancy rate, it becomes clearer why a centralized system of organ donation was implemented via a separate NHS body (NHSBT) with its own governance and management structures [36]. The NHSBT was created in 2008 and to a certain extent, its centralized opt-in system was successful in that consent rates steadily increased over the following decade before the law was changed. Nonetheless, the NHSBT has not been able to replicate the success of Spain. In 2020, a “soft” opt-out was implemented within the existing centralized national system alongside the existing opt-in system, and the two systems have been operating together in a complex way ever since. Although Spain does also offer the ability for patients to opt-in through their decision on the prior instructions document, this is rarely seen since the Spanish public trusts the organ donation system and knows that their families will always be consulted so they do not see it as important to record their life decisions. This makes the law appear more consistent and in line with a system of presumed consent, unlike in England [37].

Recommendations for Policy and Practice in England and the United Kingdom

The NHS is built on the ethos that “if it is not written down it did not happen.” This has been generally applied to mitigate any potential legal action against staff or the NHS in the future. This is partially why consent documents and protocols tend to reflect ambiguity and risk aversion when compared with Spain which appears more comfortable with the spirit of presumed consent. However this is potentially creating a context where SNODs/SRs are not able to openly and proactively emphasize the benefits of organ donation or feel fully supported to do so with families. We suggest, given a change in legislation that has changed the default for nearly 60 million citizens to support the donation of their organs after they die, unless they say otherwise, that documents and standard operating procedures, particularly in relation to consent, reflect this and are revised with a view to simplification and presumption.

The ODR also lacks legal status. Approximately 10% of families override their relatives’ opt-in decision but the same rates are not observed for opt-out decisions. Despite having an ODR, it is not mandatory to follow the organ donation decision on the register. If the ODR was given greater legal status and the decisions in it were used as a basis for the conversation with the family after death (preferably by simplifying the latter to bring it more in line with the Spanish approach to consent after death), this could make it easier for the family to support the potential donor’s decision. It may also create a context in which people are more likely to discuss what they want in terms of organ donation. Aligning language, processes and guidelines with the legislation on presumed consent may generate a more positive initial response to organ donation and help address doubts or concerns that are common in these complex end-of-life discussions.

The linking of the ODR to a patient’s medical record can also make it easier for healthcare professionals to discuss with the patient if they still stand by their recorded decision should anything life-threatening happen during their admission, similar to a “Do Not Attempt Resuscitation” form.

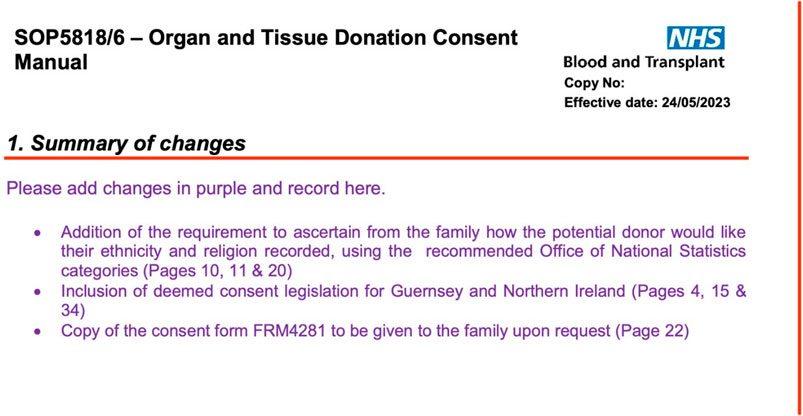

Although organ donation has expanded in Spain, the underlying principles of legal standing, guidelines and protocols have not changed substantially. Since 2021 the latest NHSBT consent manual has had six updates. The most recent updates are included in Figure 3 for reference. The consent form has undergone multiple revisions in recent years, with each iteration adding further layers of complexity and processes. This is wasteful and prevents opportunities for innovation that would benefit patients at an individual level. Any revisions to the documents need to be more mindful of the users (e.g., SNODs/SRs and acutely bereaved families) and provide a more personalized and sensitive approach to consent that is aligned with the ambitions of opt-out legislation.

Limitations

Due to resource constraints, we were not able to back-translate very long policy documents from English into Spanish. We relied on software to translate Spanish documents and then verified key concepts and processes with a small number of Spanish experts.

Policy documents alone do not entirely reflect actual practice and there is of course variation in the implementation of processes within each health system. We acknowledge this limitation and mitigated it by engaging with organ donation practitioners in Spain and England as co-authors to complement our documentary analysis with their perceptions, experiences and knowledge. There are also significant differences within and between countries that are not reflected in a discourse analysis focused on consent such as detailed public attitudes to organ donation [37, 38] as well as potential donor characteristics and methods of optimizing organ donor potential which vary widely.

Finally England has a much higher number of live donors than Spain, emphasizing the complexity of organ donation and the fact that there are more ways to increase the number of organs available, reflecting that deceased donor consent rates are not the only measure of a successful organ donation system.

Conclusion

The Spanish system has a simpler and more streamlined approach to family consent to organ donation and the documents very proactively encourage donation. If England’s ambition is to achieve the consent rates consistently seen in Spain, there may be opportunities to do so by giving greater legal protection and status to the ODR and also by changing the culture from being impartial and risk-averse toward the promotion of organ donation. Significant investment in staff and resources would also be required to match the availability of ICU beds seen in Spain as well as dedicated resources, including specialist sites, which were previously deemed too expensive to invest in. However, there are potentially modifiable issues that appear to work better in Spain such as a shorter and simpler consent process and much more positive language throughout the process, which would improve the experience of staff and acutely bereaved families. In parallel, research is needed (ideally in a controlled context [39]) to understand more about what works, for whom and why in order to maintain the supply of organs to meet the increasing demand.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Ethics Statement

The main study received favorable ethics opinions from the LSHTM Research Ethics Committee (Ref. 26427 – 20/07/2021) and from the Health Research Authority (HRA) Research Ethics Committee (Ref. 21/NW/0151 – 03/06/2021). Research approvals were received from the HRA and Health and Care Research (HCRW) Wales (IRAS project ID 297313) on 3/06/2021, and from the Research, Innovation and Novel Technologies Advisory Group (RINTAG) (ODT Study no 113; NHSBT Change Control ref: cc/11164) on 11/06/2021. This particular analysis involved comparing publicly accessible protocol and policy documents and engagement with experts by opinion, specific ethical approval for this work was not required. At the time of publication, a revised 2-page consent form has received approval from the HTA and educational research is in progress (Miller) following the implementation of opt-out.

Author Contributions

KR - undertook first draft of protocol, translation and analysis of documents, prepared the initial report and contributed to preparing the manuscript for submission. JN – conceptualised the study, reviewed the protocol, contributed to primary analysis, reviewing the draft and preparing the manuscript for submission. LM – conceptualised the study, reviewed the protocol, undertook stakeholder engagement, contributed to primary analysis, reviewing the draft and preparing the manuscript for submission. NM -Reviewed the protocol and contributed to preparing the manuscript for submission. DP-Z – contributed to data analysis, stakeholder engagement and reviewed the manuscript for submission. CM – contributed to data analysis, stakeholder engagement, contextual understanding and reviewed the manuscript for submission. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

The author(s) declare(s) that financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This study was funded by the NIHR Policy Research Programme through its core support to the Policy Innovation and Evaluation Research Unit (Project No: PR-PRU-1217-20602). The views expressed are those of the author(s) and are not necessarily those of the NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

1. NHSBT. Organ Donation Key Rates NHSBT (2022). Available from: https://app.powerbi.com/view?r=eyJrIjoiMGIxYWIyMmEtZmU0Ny00OTkwLTlmNWUtYmEyNmFlZDI1YmQyIiwidCI6ImUxMWExYjhmLThmNTItNDYwOC04Zjc2LTQ2N2ZmMWQzNGM5NiIsImMiOjh9 (Accessed May 24, 2023).

2. O’Neill, S, Thomas, K, Mc Laughlin, L, Noyes, J, Boadu, P, Williams, L, et al. Trends in Organ Donation in England, Scotland and Wales in the Context of the COVID-19 Pandemic and ‘Opt-Out Legislation’. PLoS One (2024).

3. Statista. Deceased Organ Donor Rate in Europe (2022). Available from: https://www.statista.com/statistics/537908/deceased-organ-donor-rate-in-europe (Accessed May 24, 2023).

4. Deroos, LJ, Marrero, WJ, Tapper, EB, Sonnenday, CJ, Lavieri, MS, Hutton, DW, et al. Estimated Association between Organ Availability and Presumed Consent in Solid Organ Transplant. JAMA Netw Open (2019) 2:e1912431. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.12431

5. Hulme, W, Allen, J, Manara, AR, Murphy, PG, Gardiner, D, and Poppitt, E. Factors Influencing the Family Consent Rate for Organ Donation in the UK. Anaesthesia (2016)) 71(9):1053–63. doi:10.1111/anae.13535

6. Rithalia, A, McDaid, C, Suekarran, S, Myers, L, and Sowden, A. Impact of Presumed Consent for Organ Donation on Donation Rates: A Systematic Review. BMJ (2009) 338(7689):a3162–7. doi:10.1136/bmj.a3162

7. Becker, F, Roberts, KJ, De Nadal, M, Zink, M, Stiegler, P, Pemberger, S, et al. Optimizing Organ Donation: Expert Opinion from Austria, Germany, Spain and the U.K. Ann Transpl (2020) 25:e921727. doi:10.12659/AOT.921727

9. Noyes, J, McLaughlin, L, Morgan, K, Roberts, A, Moss, B, Stephens, M, et al. Process Evaluation of Specialist Nurse Implementation of a Soft Opt-Out Organ Donation System in Wales. BMC Health Serv Res (2019) 19:414. doi:10.1186/s12913-019-4266-z

10. Policy Innovation and Evaluation Research Unit. Evaluation of Changes to Organ Donation Legislation in England (2019). Available from: https://piru.ac.uk/projects/current-projects/evaluation-of-changes-to-organ-donation-legislation-in-england.html (Accessed May, 2024).

11. Mc Laughlin, L, Mays, N, Al-Haboubi, M, Williams, L, Bostock, J, Boadu, P, et al. Potential Donor Family Behaviours, Experiences and Decisions Following Implementation of the Organ Donation (Deemed Consent) Act 2019 in England: A Qualitative Study. Intensive Crit Care Nurs (2024).

12. Al-Haboubi, M, Mc Laughlin, L, Noyes, J, Williams, L, Bostock, J, and Boadu, P. Perceptions and Experiences of Healthcare Professionals of Implementing the Organ Donation (Deemed Consent) Act in England during the Covid-19 Pandemic. BMC Health Serv Res (2024).

13. Streit, S, Johnston-Webber, C, Mah, J, Prionas, A, Wharton, G, Casanova, D, et al. Ten Lessons from the Spanish Model of Organ Donation and Transplantation. Transpl Int (2023) 36:11009. doi:10.3389/ti.2023.11009

14. ONT. Framework Protocol for Organ and Tissue Donation in the Private Sector Healthcare Facilities in Collaboration with the Public (2019). Available from: https://www.ont.es/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/PROTOC1.pdf (Accessed May 22, 2023).

15. State Agency Official State Gazette. Order SSI/2396/2014 Establishing the Basis of the Quality and Safety Framework Program for the Procurement and Transplantation of Human Organs and Establishing the Information Procedures for its Exchange with Other Countries (2014). Available from: https://www.boe.es (Accessed May 22, 2023).

16. ONT. Asystole Donation in Spain: Current Situation and Recommendations. Document of National Consensus (2012). Available from: https://www.ont.es/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/Doc-de-Consenso-Nacional-sobre-Donacion-en-Asistolia.-Ano-2012.pdf (Accessed May 22, 2023).

17. ONT. Quality Improvement Programme (2019), Available from: https://www.ont.es/informacion-a-los-profesionales-4/programa-de-calidad-del-proceso-de-donacion-4-8/, [Accessed May 22 2023].

18. Ministry of Health Social Services and Equity. Royal Decree 1723-2012 of 28 December (2012). Available from: https://www.global-regulation.com/translation/spain/1491185/royal-decree-1723---2012%252c-of-28-december%252c-which-regulates-the-activities-of-procurement%252c-clinical-use-and-territorial-coordination-of-human-orga.html (Accessed May 22, 2023).

19. ONT. Emergency Professionals and the Process of Donation (2015). Available from: https://www.ont.es/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/ELPROF1.pdf (Accessed May 22, 2023).

20. NHSBT. Organ and Tissue Donation Consent Manual (2021). Available from: https://nhsbtdbe.blob.core.windows.net/umbraco-assets-corp/21508/organ-and-tissue-donation-consent-manual-sop5818.pdf (Accessed may 22, 2023).

21. Human Tissue Authority. Code of Practice Code A: Guiding Principles and the Fundamental Principle of Consent (2020). Available from: https://content.hta.gov.uk/sites/default/files/2020-11/Code%20A.pdf (Accessed May, 2020).

22. NHSBT. Consent for Organ And/or Tissue Donation FORM FRM4281/8 (2021). Available from: https://nhsbtdbe.blob.core.windows.net/umbraco-assets-corp/21509/consent-for-organ-and-or-tissue-donation-frm4281.pdf (Accessed May 22, 2023).

23. Fox, DE, Donald, M, Chong, C, Quinn, RR, Ronksley, PE, Elliott, MJ, et al. A Qualitative Content Analysis of Comments on Press Articles on Deemed Consent for Organ Donation in Canada. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol (2022) 17(11):1656–64. doi:10.2215/CJN.04340422

24. Hsieh, HF, and Shannon, SE. Three Approaches to Qualitative Content Analysis. Qual Health Res (2005) 15(9):1277–88. doi:10.1177/1049732305276687

25. Galasiński, D, and Sque, M. Organ Donation agency: A Discourse Analysis of Correspondence between Donor and Organ Recipient Families. Sociol Health Illn (2016) 38(8):1350–63. doi:10.1111/1467-9566.12478

26. Mogashoa, T. Understanding Critical Discourse Analysis in Qualitative Research. Int J Humanities Soc Sci Edu (2014) 1(7):104–13.

27. Greckhamer, T, and Cilesiz, SR. Transparency, Evidence, and Representation in Discourse Analysis: Challenges and Recommendations. Int J Qual Methods (2014) 13(1):422–43. doi:10.1177/160940691401300123

28. Harvey, D. Management of Perceived Devastating Brain Injury after Hospital Admission a Consensus Statement Consensus Group Membership Endorsing Organisations (2018). doi:10.1177/1751143716670410

29. Manara, A, and Thomas, I. Current Status of Organ Donation after Brain Death in the UK. Anaesthesia (2020) 75(9):1205–14. doi:10.1111/anae.15038

30. Manara, A, Rubino, A, and Tisherman, S. ECPR and Organ Donation: Emerging Clarity in Decision Making. Resuscitation (2023) 193:110035. doi:10.1016/j.resuscitation.2023.110035

31. World Population Review. ICU Beds Per Capita by Country (2024). Available from: https://worldpopulationreview.com/country-rankings/icu-beds-per-capita-by-country (Accessed May 22, 2023).

32. Rudge, CJ. Organ Donation: Opting in or Opting Out? Br J Gen Pract (2018) 68(667):62–3. doi:10.3399/bjgp18X694445

33. Nuffield Trust. Hospital Bed Occupancy (2023). Available from: https://www.nuffieldtrust.org.uk/resource/hospital-bed-occupancy (Accessed May 22, 2023).

34. Martín-Delgado, MC, Martínez-Soba, F, Masnou, N, Pérez-Villares, JM, Pont, T, Sánchez Carretero, MJ, et al. Summary of Spanish Recommendations on Intensive Care to Facilitate Organ Donation. Am J Transpl (2019) 19(6):1782–91. doi:10.1111/ajt.15253

35. Noyes, J, Mclaughlin, L, Morgan, K, Roberts, A, Moss, B, Stephens, M, et al. Process Evaluation of Specialist Nurse Implementation of a Soft Opt-Out Organ Donation System in Wales. BMC Health Serv Res (2019) 19:414. doi:10.1186/s12913-019-4266-z

36. Johnston-Webber, C, Mah, J, Prionas, A, Streit, S, Wharton, G, Forsythe, J, et al. Solid Organ Donation and Transplantation in the United Kingdom: Good Governance Is Key to Success. Transpl Int (2023) 36:11012. doi:10.3389/ti.2023.11012

37. Díaz-Cobacho, G, Cruz-Piqueras, M, Delgado, J, Hortal-Carmona, J, Martínez-López, MV, Molina-Pérez, A, et al. Public Perception of Organ Donation and Transplantation Policies in Southern Spain. Transpl Proc (2022) 54(3):567–74. doi:10.1016/j.transproceed.2022.02.007

38. Boadu, P, McLaughlin, L, and Noyes, J. Subgroup Differences in Public Attitudes, Preferences, and Self-Reported Behaviour Related to Deceased Organ Donation before and after the Introduction of the ‘soft’ Opt-Out Consent System in England: Mixed-Methods Study. BMC Heal Serv Res (2024).

Keywords: organ donation, consent, England, Spain, opt-out

Citation: Rees K, Mclaughlin L, Paredes-Zapata D, Miller C, Mays N and Noyes J (2024) Qualitative Content and Discourse Analysis Comparing the Current Consent Systems for Deceased Organ Donation in Spain and England. Transpl Int 37:12533. doi: 10.3389/ti.2024.12533

Received: 06 December 2023; Accepted: 10 June 2024;

Published: 04 July 2024.

Copyright © 2024 Rees, Mclaughlin, Paredes-Zapata, Miller, Mays and Noyes. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Leah Mclaughlin, bC5tY2xhdWdobGluQGJhbmdvci5hYy51aw==; Jane Noyes, amFuZS5ub3llc0BiYW5nb3IuYWMudWs=

Kate Rees

Kate Rees Leah Mclaughlin

Leah Mclaughlin David Paredes-Zapata

David Paredes-Zapata Cathy Miller

Cathy Miller Nicholas Mays

Nicholas Mays Jane Noyes

Jane Noyes