Introduction

Narcotic drug abuse is one of the most serious social problems in the world, and China is highly vulnerable to its negative consequences [1–3]. From a supply chain perspective, narcotics from an illicit opium-producing area in the infamous “Golden Triangle” [4], pose one of the largest threats to the Chinese border and inland areas. There is a high frequency of cross-border drug trafficking and crime, especially along the Yunnan and Guangxi Provinces. As van Schendel and Abraham argued, the border is a place of extreme anxiety for the modern state due to a poor understanding of the notion of illegality [5].

The Chinese government has made great efforts to address and control these drug problems, but still faces major challenges in the fight against drug trafficking and crimes due to transnational illicit flows, especially in China’s Southeast Asian borderlands, where there is a long history of opium/heroin production, consumption, and trade [6–8].

In this context, much of the debate about narcotic drug problems in this border area is concerned with how to control supply [9], while we know much less about how narcotic drug problems affect or change the livelihoods of drug users and societies on the consumer side. In fact, many drug users in this region live in rural areas and work in agriculture [10]. There is therefore a gap in research concerning their livelihoods after drug abuse or cessation. Unlike other threats from non-traditional security issues, such as climate change or serious diseases, only certain or targeted villagers may suffer from drug abuse, and among these villagers, some of them may recover after receiving medical treatment. However, this does not mean that those who recover have completely stopped abusing drugs and it is still possible for them to relapse. In addition, drug users are not easy to locate and apprehend immediately because of their high mobility and ability to hide. Therefore, a better understanding of these issues will be useful when thinking about cross-border/transnational linkages, border governance, and sustainable rural development issues in the borderlands and other regions facing similar challenges.

Reconsidering the characteristics of drug users

Unlike conventional approaches to understanding rural populations, such as those based on gender, age, or wealth, there are specific characteristics associated with drug users. Apart from those who are still abusing drugs, the majority of former drug users require medical treatment in order to recover. In terms of medical treatment and relapse, drug users normally lose the physical feeling of addiction once they are forced to stay in a rehabilitation center and can fully recover after receiving 1 month of continuous and professional treatment. However, the case of compulsory punishment is different. These recovered drug addicts are very likely to relapse when they are released. There are a few possible reasons for this: 1) Physical and mental dependence on drugs results from physiological damage after drug addiction. For example, being addicted to heroin only once can result in a strong mental dependence on drugs. 2) They are easily affected by items related to drug abuse, such as a syringe and aluminum foil, which may encourage them to abuse drugs again. 3) Widespread discrimination from their families and society can trigger a relapse. 4) They are easily disappointed in themselves if it is relatively difficult for them to thrive when re-entering society. In this complicated context, it is imperative to understand the agrarian livelihoods affected by narcotic drugs rather than comparing them to those who have never abused drugs.

Typologies of agrarian livelihoods affected by narcotic drugs

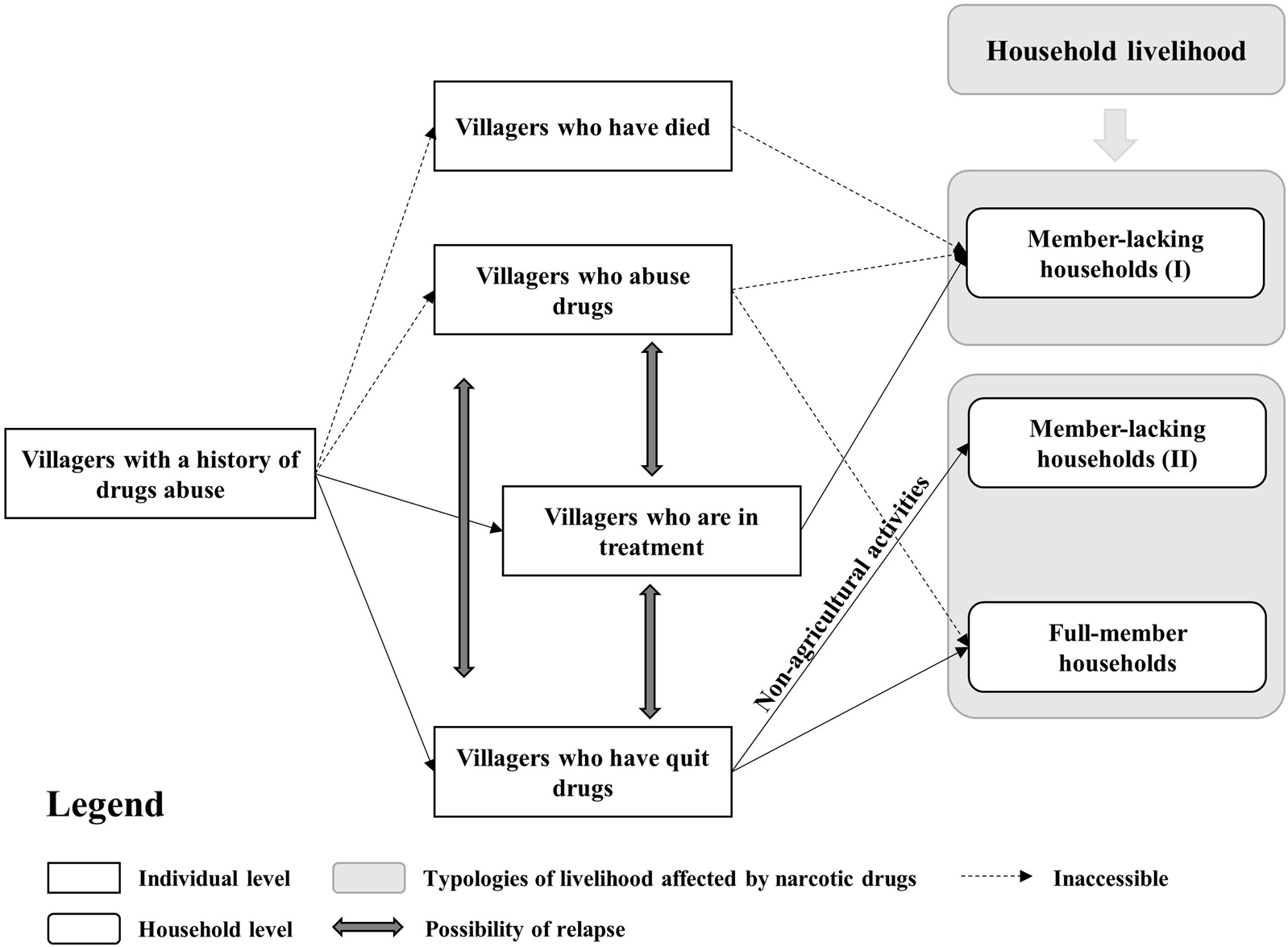

For a better understanding of how narcotic drugs have affected the local villagers and their households, this paper proposes four typologies of villagers with drug abuse experience based on the characteristics of drug abusers (Figure 1). The first group included villagers who passed away due to drug addiction. The second group was made up of villagers who were currently abusing drugs. However, these two groups were very difficult to access and interview because of practical and ethical considerations. The third group included villagers who were under treatment in the drug addiction treatment center. These were villagers who had been using drugs for a long time and had been sent to the drug treatment center. The fourth and last group consisted of villagers who had stopped using narcotic drugs after treatment. Villagers belonging to the last group had returned to lead normal lives. Nevertheless, there is a possibility of relapse among the villagers who are under treatment or have completed treatment because of their strong dependence on narcotic drugs both mentally and physically. In general, there was a high possibility of recurrence and uncertainty among the last three groups.

FIGURE 1

A typology linking villagers having experienced drug abuse and agrarian livelihoods.

The villagers belonging to the above groups generally formed two types of households (Figure 1). The first type included member-lacking households (MHHs), which means that the previous and normal household structure may have been affected and some family members may have left because of drug addiction. In an MHH, some members of a household may have passed away, some may still be abusing drugs, some may be in treatment, or some may have left treatment to seek non-agricultural opportunities. The absent family member resulted in a potential labor shortage at home and may not have directly contributed to the household’s operation. Therefore, MHHs were further divided into two sub-types: MHHs-I and MHHs-II. MHHs-I represented households with members who experienced drug abuse and could not contribute to the household, while MHHs-II referred to households with members who were drug abusers but worked as agricultural or non-agricultural laborers. The second type of household was the opposite of the first: full-member households (FHHs). This may include members who were stillabusing drugs and living with their families or members who had quit drug addiction for several years and mainly made a living through agricultural activities or local work. Many studies have shown that labor capacity, education, and health levels have a positive impact on off-farm employment or engagement in non-agricultural work. However, it remains unclear whether these factors contribute to the ability of former drug users to participate in non-agricultural work.

Discussion

Drug abuse in China’s Southeast Asian borderlands is not merely a drug issue, but an urgent social and cultural agenda. It has significantly affected rural society on the Chinese side as a receiving frontier for illicit flows of narcotic drugs. From a typological perspective, this opinion article focuses on the characteristics of villagers and their respective households that are heterogeneously affected by narcotic drugs. The proposed typology is relevant to the existing literature on rural livelihoods, in addition to policies for governance, poverty alleviation, and sustainable rural development under the influence of narcotic drugs in China’s Southeast Asian borderlands and other regions facing similar challenges. It also highlights some practical considerations. First, as mentioned in the typology section, it is difficult to study the impact of narcotic drug problems on local livelihoods and we must be careful of the interviewees’ feelings when asking about drug addiction in the household. This is because such questions could easily make the interviewees feel ashamed, embarrassed, or sad. Second, this proposed typology mainly focuses on the characteristics of the villagers with prior experience of drug abuse and their households, rather than comparing the households with and without members who have previously or currently dealt with drug abuse. Such comparison would be much more complicated. For example, some villagers may be renting out their farmland not only because their labor capacity has been negatively influenced by drug abuse or disease, but also because of the costs and benefits of farming activities or as land tenants. These factors may overlap. Such situations should be further clarified and discussed in future research.

Statements

Author contributions

The author confirms being the sole contributor of this work and has approved it for publication.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This research was conducted with financial support from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 42201108).

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

1.

Chen X Zhou Y-H Ye M Wang Y Duo L Pang W et al Burmese injecting drug users in Yunnan play a pivotal role in the cross-border transmission of HIV-1 in the China-Myanmar border region. Virulence (2018) 9(1):1195–204. 10.1080/21505594.2018.1496777

2.

Lu L Jia M Ma Y Yang L Chen Z Ho DD et al The changing face of HIV in China. Nature (2008) 455:609–11. 10.1038/455609a

3.

Office of China National Narcotics Control Commission. Annual report on drug control in China, 2022, Beijing (2023). (in Chinese).

4.

Sturgeon JC . Cross‐border rubber cultivation between China and Laos: regionalization by Akha and Tai rubber farmers. Singapore J Trop Geogr (2013) 34:70–85. 10.1111/sjtg.12014

5.

van Schendel W Abraham I . Illicit flows and criminal things: States, borders, and the other side of globalization. Indiana University Press (2005).

6.

Cohen PT . The post-opium scenario and rubber in northern Laos: alternative Western and Chinese models of development. Int J Drug Pol (2009) 20:424–30. 10.1016/j.drugpo.2008.12.005

7.

Jia Y Sun J Fan L Song D Tian S Yang Y et al Estimates of HIV prevalence in a highly endemic area of China: dehong prefecture, Yunnan province. Int J Epidemiol (2008) 37:1287–96. 10.1093/ije/dyn196

8.

Su X . Nontraditional security and China's transnational narcotics control in northern Laos and Myanmar. Polit Geogr (2015) 48:72–82. 10.1016/j.polgeo.2015.06.005

9.

Meehan P Dan SL . Drugs and extractivism: opium cultivation and drug use in the Myanmar-China borderlands. J Peasant Stud (2023) 1–38. 10.1080/03066150.2023.2271403

10.

Xiao Y Kristensen S Sun J Lu L Vermund SH . Expansion of HIV/AIDS in China: lessons from Yunnan province. Soc Sci Med (2007) 64:665–75. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.09.019

Summary

Keywords

livelihood, narcotics, borderland, typology, China

Citation

Hua X (2024) Rethinking agrarian livelihoods affected by narcotic drug abuse on China’s Southeast Asian borders: a typological perspective. Adv. Drug Alcohol Res. 4:12693. doi: 10.3389/adar.2024.12693

Received

16 January 2024

Accepted

17 April 2024

Published

09 May 2024

Volume

4 - 2024

Edited by

Emmanuel Onaivi, William Paterson University, United States

Reviewed by

Qing-Rong Liu, National Institute on Aging (NIH), United States

Updates

Copyright

© 2024 Hua.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Xiaobo Hua, huaxb@cau.edu.cn

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.