- Department of Biological Sciences, University of South Carolina, Columbia, SC, United States

Dystonia-PRKRA (DYT-PRKRA), previously termed dystonia 16 (DYT16), is a movement disorder which currently has very limited treatments available and no cure. To develop effective therapeutic options, it is essential to characterize the underlying pathophysiology and identify potential drug targets. This review summarizes the recent studies that shed light on the molecular mechanisms involved in DYT-PRKRA pathogenesis. PRKRA gene encodes for the protein PACT (Protein Activator of the Protein Kinase R) and individuals with DYT-PRKRA mutations develop early-onset generalized dystonia. While the precise mechanisms linking PRKRA mutations to neuronal etiology of dystonia remain incompletely understood, recent research indicates that such mutations cause dysregulation of signaling pathways involved in cellular stress response as well as in production of antiviral cytokines interferons (IFNs). This review focuses on the effect of DYT-PRKRA mutations on the known cellular functions of PACT.

Introduction

Dystonia is a neurological movement disorder characterized by involuntary and intermittent or sustained muscle contractions leading to abnormal, repetitive twisting movements and/or abnormal postures [1]. This condition can have diverse manifestations, affecting specific muscle groups or the entire body, leading to a loss of coordinated movements [2]. It is a highly heterogeneous neurological movement disorder both clinically and genetically and in recent years many important genetic as well as molecular insights have suggested several therapeutic drug targets [3]. However, the translation of such knowledge into new therapies is yet to emerge as developing effective drugs involves in-depth research on identified genes, requiring significant resources and time. The genetically inherited monogenic dystonia manifests in various forms; each one characterized by distinct features [2]. Focal Dystonia targets specific body regions, such as the neck (cervical dystonia), eyelids (blepharospasm), hand (writer’s cramp), or vocal cords (spasmodic dysphonia). In contrast, segmental dystonia impacts adjacent body parts, potentially combining areas like cervical and oromandibular dystonia. Generalized dystonia extends its reach across multiple or all body parts, exerting a notable influence on both upper and lower extremities, thereby affecting mobility and posture. Hemidystonia uniquely affects one side of the body, inducing muscle contractions and abnormal movements. Multifocal dystonia involves multiple non-contiguous body parts, presenting a diverse clinical picture. Task-Specific dystonia emerges during specific activities, such as musician’s dystonia or writer’s cramp and paroxysmal dystonia is marked by intermittent episodes of dystonia. This spectrum highlights the complex nature of dystonia and the various ways it can manifest in affected individuals.

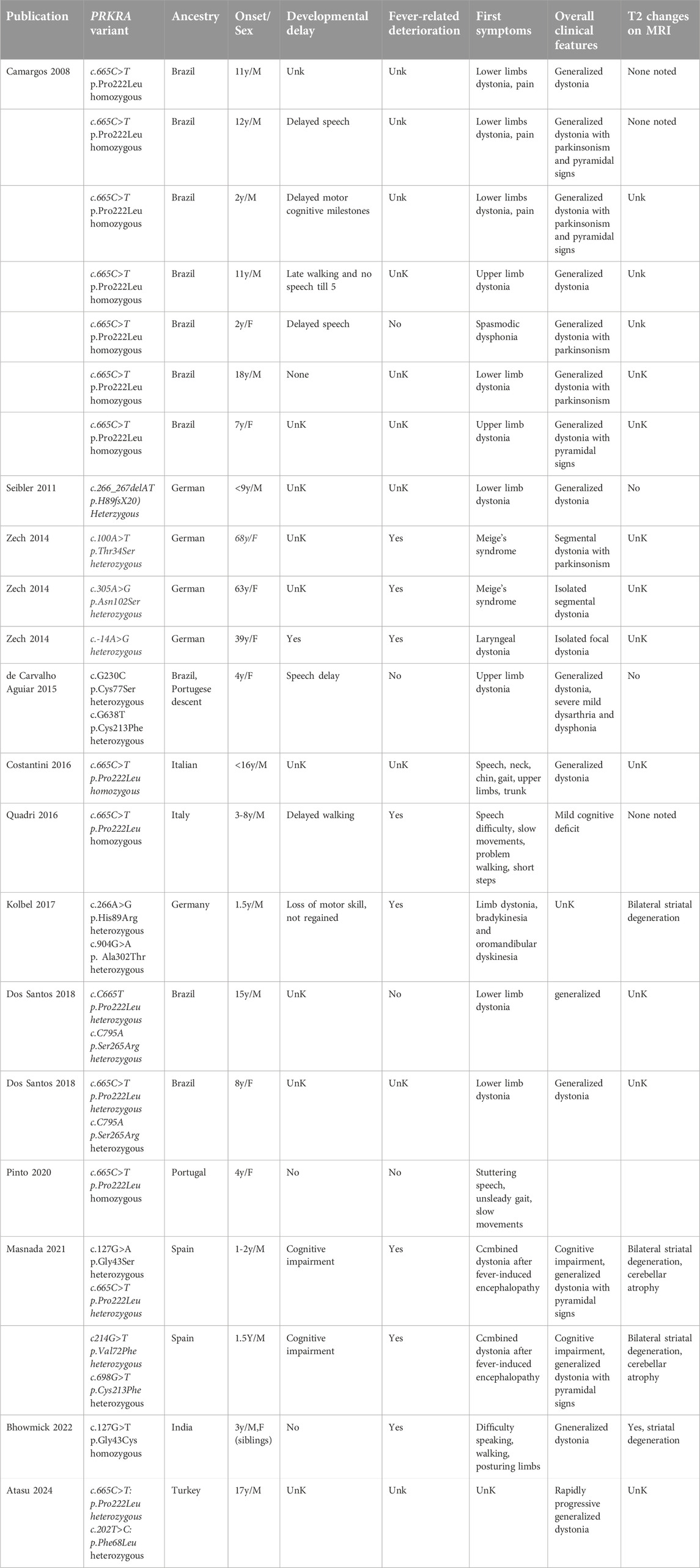

DYT-PRKRA is caused by mutations in the PRKRA gene (OMIM: 612067), which encodes the protein activator (PACT) of the interferon-induced protein kinase PKR [4]. The characteristics of DYT-PRKRA patients have been summarized in a recent review [2] and in Table 1. The vast majority of PRKRA mutation carriers show generalized dystonia, but some patients with segmental/multifocal dystonia or focal dystonia have been noted. DYT-PRKRA most often starts in the limbs (upper > lower), sometimes cervical or laryngeal, and rarely in the neck. Tremor was reported in some patients, myoclonus in none of them, and Parkinsonism was described in about half the patients. Information on psychiatric signs and other nonmotor symptoms is rarely indicated but cognitive impairment and global developmental delay especially after a childhood febrile illness has been noted [5–9]. The age of onset was reported to be early during childhood in most cases but later onset during adulthood has been observed indicating environmental or other modifying genetic factors. Abnormalities and degeneration in striatal region have been noted in a few patients but this information was not available for most patients [6–8]. Investigations into structural brain changes in DYT-PRKRA patients remain ongoing and a possible neurodegenerative classification of DYT-PRKRA can be considered after such analysis in additional DYT-PRKRA patients. The globus pallidus internus (GPi) region has evolved as a potential target for deep brain stimulation (DBS) and GPi-DBS is used as a therapeutic intervention for several types of dystonia [10]. However, GPi-DBS has not shown much benefit in several DYT-PRKRA patients and other established treatments including botulinum toxin injections, baclofen, and benzodiazepines were shown not to be beneficial [2]. In one case, DYT-PRKRA was reported to improve after thiamine therapy [11], but this has not been reported in other cases. Thus, understanding the molecular mechanisms responsible for DYT-PRKRA is a priority of significant importance for developing novel and effective treatment options.

Functional domains of PACT and DYT-PRKRA mutations

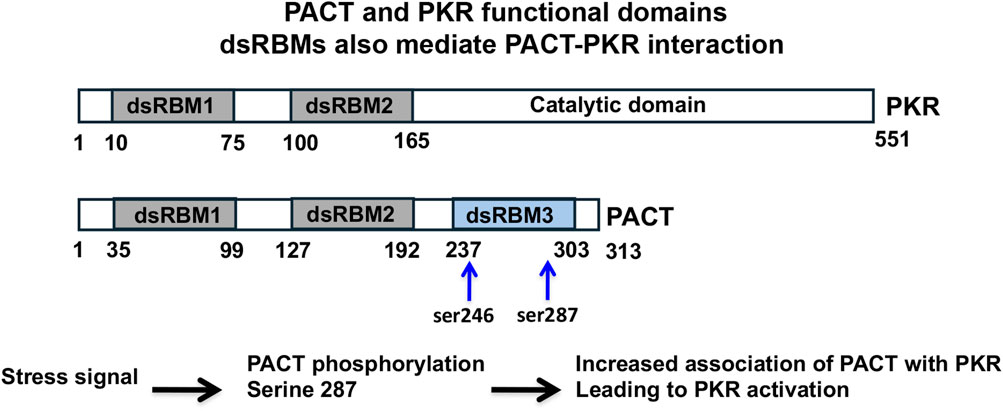

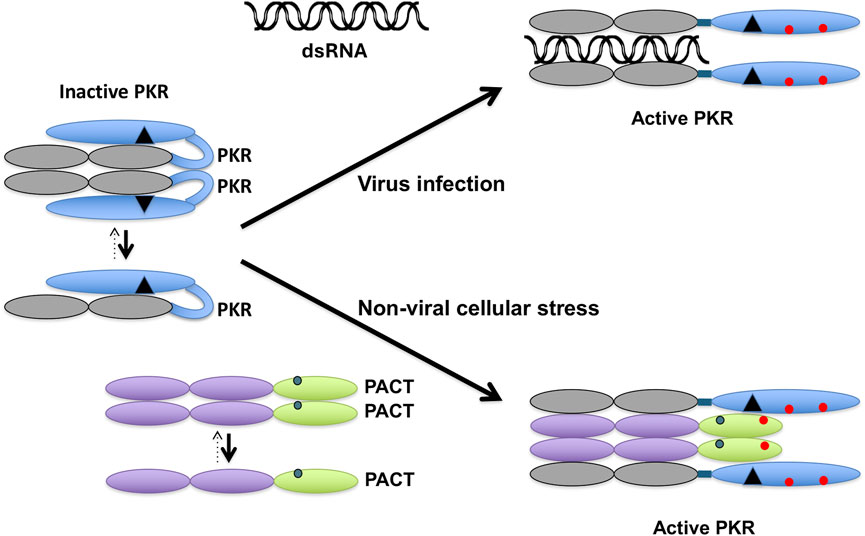

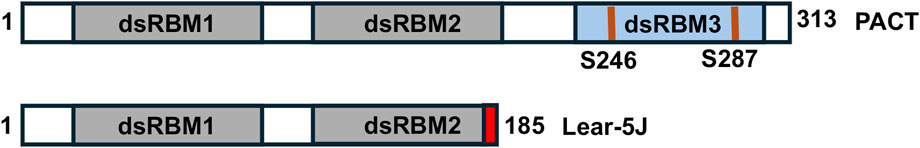

The most studied function of PACT is its role in catalytic activation of the interferon-induced protein kinase PKR (protein kinase, RNA activated) via a direct interaction. PKR (aka EIF2AK2) is a serine threonine protein kinase that was originally discovered in the context of antiviral innate immune response [12]. PKR is ubiquitously expressed at low constitutive levels and its kinase activity stays latent until bound by an activator. Upon binding to one of its two activators: i) double-stranded (ds) RNA [13], or ii) protein activator PACT [4] PKR undergoes autophosphorylation and enzymatic activation. The dsRNA-dependent PKR activation occurs mainly during viral infections [14], and in uninfected cells PACT activates PKR in response to oxidative stress, endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress, and serum deprivation [15, 16]. Patel and Sen cloned and identified PACT as a stress-modulated protein activator of PKR in 1998 [4]. Since then, the functional involvement of PACT-mediated PKR activation in regulating cellular response to diverse types of stress signals has been studied extensively [15, 17–19]. The functional domains of PKR and PACT have been characterized in detail and both PACT and PKR have the evolutionarily conserved dsRNA binding motifs (dsRBMs) [20–22] that also mediate the dsRNA independent protein-protein interactions between them and with other proteins that contain dsRBMs [23–25] (Figure 1). Upon binding dsRNA or PACT via the dsRBMs, PKR undergoes a conformational change which results in the autophosphorylation and activation of PKR [26, 27]. PACT is a stress-modulated activator of PKR that acts via a dsRNA-independent interaction in response to ER stress, oxidative stress, and serum deprivation [15, 16, 28]. Of the three dsRBMs present in PACT, the two amino terminal motifs dsRBM1 and 2, are critical for dsRNA binding and PACT-PKR interaction and a carboxy terminal dsRBM3 motif that does not bind dsRNA is essential for PKR activation [4, 23, 24]. Within dsRBM3, serines 246 and 287 serve as phosphorylation sites to enhance PACT-PACT homomeric interaction and the heteromeric interaction of PACT’s dsRBM3 with PKR’s catalytic domain that takes place only after PACT undergoes a stress-induced phosphorylation of serine 287 [19, 29] (Figure 2). In the absence of stress, PACT is constitutively phosphorylated on S246 [29], associates with PKR weakly [30] and is unable to activate PKR. Once phosphorylated on serine 287 in response to cellular stress, PACT’s affinity tor PACT-PACT and PACT-PKR interactions increases, thereby leading to efficient PKR association and catalytic activation [17, 30].

Figure 1. Functional domains of PACT (aka PRKRA) and PKR (aka EIF2AK2). The conserved dsRBMs are depicted as grey boxes and the third dsRBM in PACT is depicted as a blue box. The dsRBM3 lacks essential basic amino acids and cannot bind dsRNA but mediates interaction with PKR like dsRBM1 and 2. The numbers indicate the amino acid positions and the locations of constitutive (S246) and stress-induced phosphorylation (S287) of PACT are indicated by blue arrows.

Figure 2. PACT activates PKR in response to non-viral cellular stress. In the absence of stress, PKR exists in an inactive conformation primarily as a monomer. The dsRNA produced during viral infections binds to PKR via its dsRBMs (grey ovals) to induce a conformational change and dimerization that opens PKR’s catalytic domain (blue oval) to cause its autophosphorylation (red circles). In the absence of any cellular stress, PACT exists primarily as a monomer with serine 246 phosphorylation (blue circle). In the presence of non-viral cellular stress, PACT is phosphorylated on serine 287 (red circle), which promotes its dimerization and association with PKR. When The dsRBMs 1 and 2 of PACT (purple ovals) interact with PKR’s two dsRBMs and dsRBM3 of PACT (green oval) interacts with the PACT-binding motif (PBM, black triangle) in PKR’s catalytic domain to bring about the conformational change in PKR to activate it via dimerization and autophosphorylation.

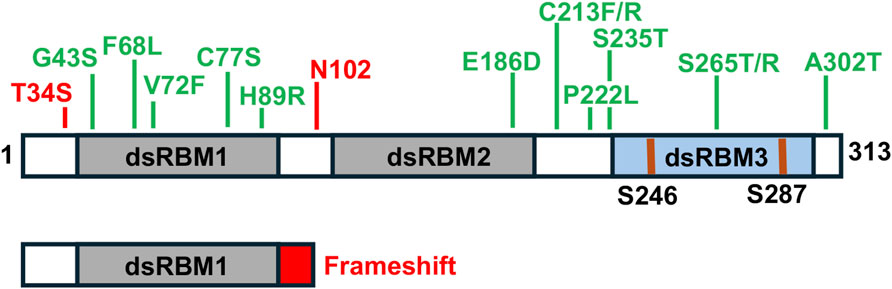

In last few years, several mutations have been identified (Figure 3) in PRKRA gene (OMIM: DYT16, 612067) leading to DYT-PRKRA [5–9, 31–40]. Although DYT-PRKRA was originally described to have an autosomal recessive inheritance pattern [31] but dominantly inherited variants of DYT-PRKRA have also been reported [32, 38]. Most mutations reported in DYT-PRKRA are substitution mutations that map within either the dsRBM1 and 2 or in the linker region between dsRBM2 and dsRBM3. One frameshift mutation reported in a single patient produces an early stop codon and truncates the PACT protein within dsRBM1 [32]. It is unclear if such a truncated protein would be present in the patient as no study has been conducted on patient cells. However, this truncated protein if present, will be unable to activate PKR via a direct interaction as dsRBM3 is essential for PKR activation. It is important to note that in several of DYT-PRKRA cases, developmental regression and dystonia was first noted after a febrile illness in the childhood [5–9]. This detail becomes relevant in the context of the cellular functions of PACT discussed in this review. The effects of one frameshift and several substitution mutations on PACT’s functional contribution to various cellular pathways has been studied and is discussed in the next section of this review [41–44].

Figure 3. DYT-PRKRA mutations. Locations of various substitution mutations and one frameshift mutation are indicated in the context of PACT’s functional motifs. Grey boxes: dsRBM1 and 2, Blue box: dsRBM3. The phosphorylated serines 246 and 287 shown as blue lines.

The effect of DYT-PRKRA mutations on the known cellular functions of PACT

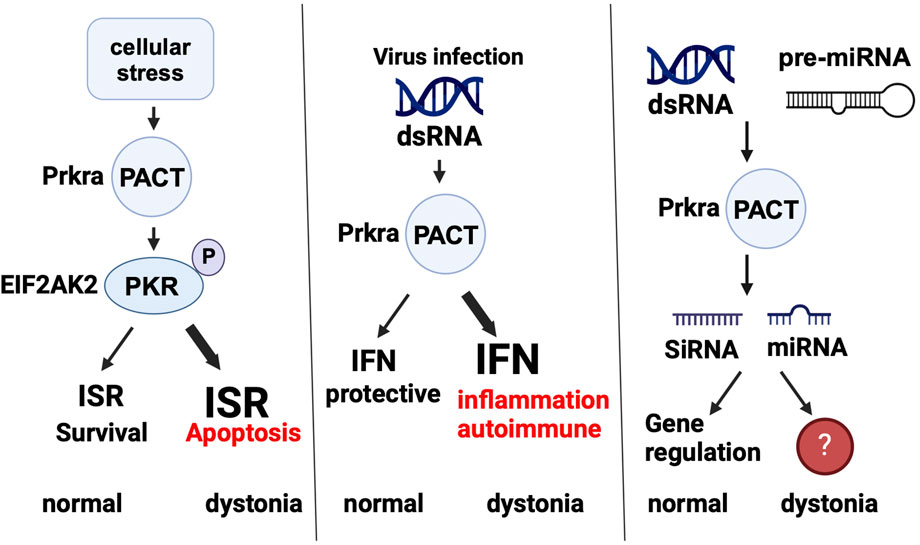

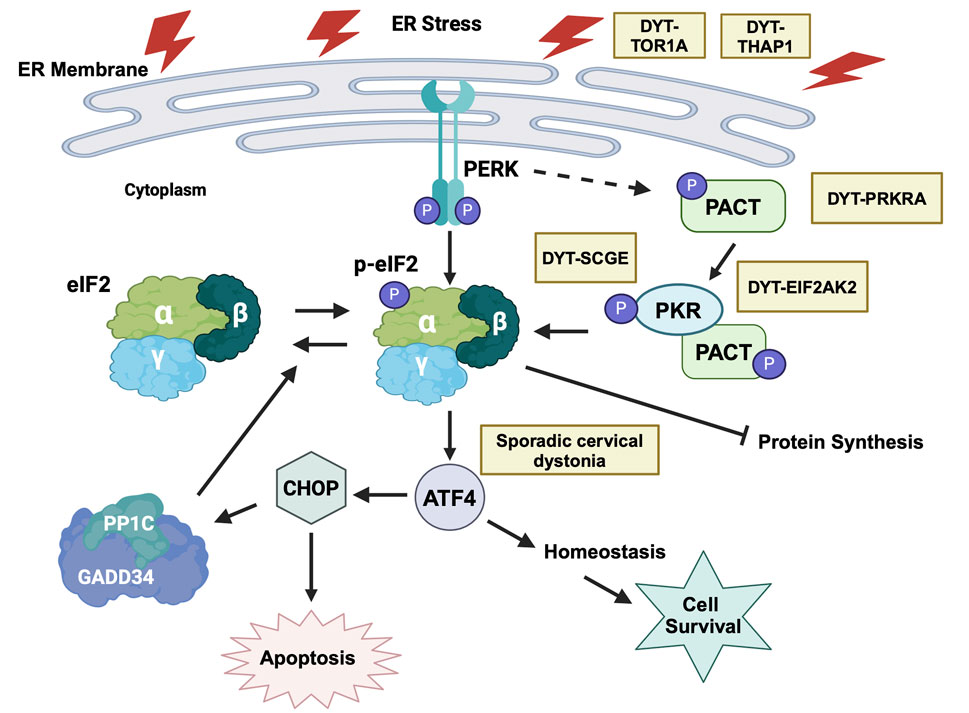

PACT impacts cellular regulation via its participation in several pathways relevant to dystonia and Figure 4 summarizes these pathways as well as how they are altered in DYT-PRKRA to affect cellular responses and function.

Figure 4. PACT is part of several cellular pathways. PACT’s normal function in ISR, innate immunity, and RNAi pathways is shown and how the normal functioning is affected in dystonia (if known) is also depicted. ISR: integrated stress response, IFN: interferon, SiRNA: small interfering RNA, miRNA: microRNA. Created in BioRender. Patel, R. (2025) https://BioRender.com/j98s943.

PKR activation and integrated stress response (ISR)

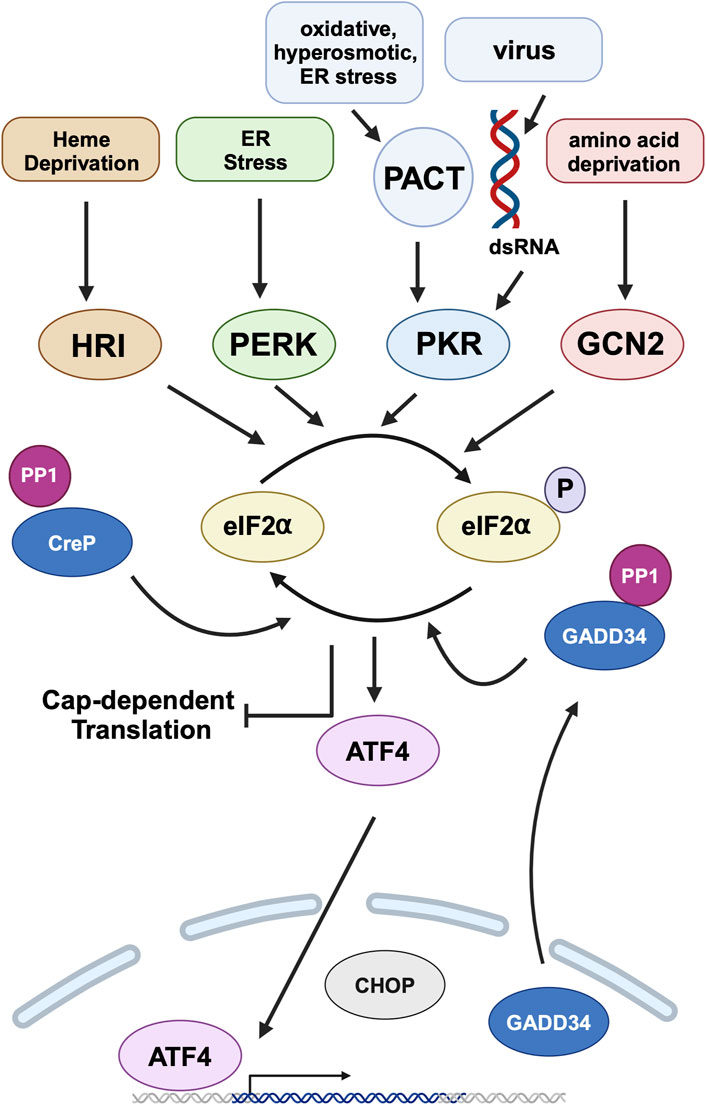

PACT-mediated PKR activation occurs in response to diverse types of stress signals [15, 17–19]. Once activated, PKR phosphorylates the α subunit of eukaryotic initiation factor 2 (eIF2α) on serine 51 and inactivates it thereby causing a general block in protein synthesis [45]. Phosphorylation of eIF2α is a central regulatory event for the ISR [46, 47], which helps cells recover appropriately from a variety of biological stresses (Figure 5). Although phosphorylation of eIF2α causes a general block in protein synthesis, it stimulates the translation of a selected few mRNAs that have upstream, short upstream open reading frames (uORFs) in their 5′ untranslated regions (5′UTRs) [48–51]. These preferentially translated mRNAs encode various stress response regulators such as the transcription factors activating transcription factor 4 (ATF4) and C/EBP-homologous protein (CHOP) that reprogram the transcriptome for adaption to stress, and trigger eIF2α dephosphorylation to promote ISR termination [52–54]. The duration and extent of the stress response is regulated by several mechanisms. For instance, ATF4 regulates the transcription of growth arrest DNA damage-inducible 34 (GADD34), which is essential for translational recovery towards survival [55, 56], and of CHOP, whose accumulation plays a pivotal role in converting the stress response from an adaptive phase to apoptosis when the ISR is overwhelmed [57–59]. The intensity, duration and kinetics of eIF2α phosphorylation as well as the nature of the downstream activated cascades determine whether a cell adapts and survives, or instead dies, in response to stress. Thus, activation of PKR by PACT if not regulated appropriately can be associated with a prolonged shutdown of protein translation, activation of caspase-8, poly ADP ribose polymerase 1(PARP1) cleavage and apoptosis [45, 60, 61].

Figure 5. Integrated stress response (ISR) and PACT. Heme deprivation, amino acid starvation, ER stress, viral infection, and other cellular stress signals activate Heme regulated inhibitor (HRI), general control nonderepressible (GCN2), PKR-like endoplasmic resident kinase (PERK), and Protein kinase, RNA activated (PKR) kinases that phosphorylate eIF2α, the central event of ISR. PKR is activated by dsRNA during viral infections and by PACT in response to non-viral stress signals. This leads to global attenuation of cap-dependent translation while simultaneously promoting preferential translation of specific mRNAs, such as activating transcription factor 4 (ATF4). ATF4 is the main effector transcription factor of the ISR. It regulates the expression of genes involved in cellular adaptation. ISR is terminated by the constitutively expressed constitutive repressor of eIF2α phosphorylation (CReP) and stress-induced growth arrest and DNA damage-inducible 34 (GADD34), both of which are regulatory subunits of protein phosphatase 1 (PP1) that dephosphorylates eIF2α. DYT-PRKRA mutations cause a dysregulation of ISR to cause enhanced apoptosis in response to ER stress. Created in BioRender. Patel, R. (2025) https://BioRender.com/w13b787.

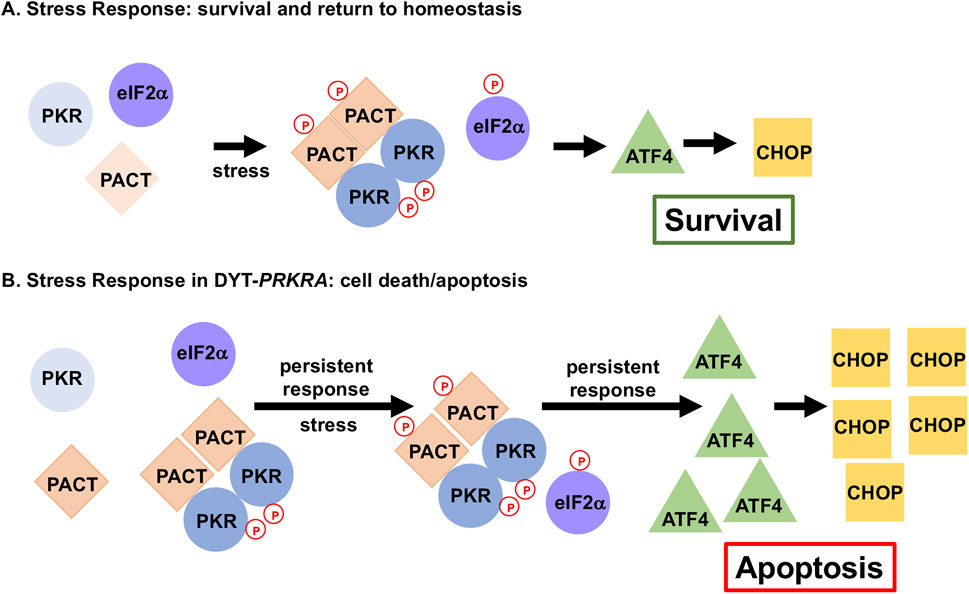

Many DYT-PRKRA mutations have been characterized for their effects on PKR activation and ISR (Figure 6). A recessively inherited P222L mutation increases cell susceptibility to endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress through the dysregulation of ISR signaling in patient derived lymphoblasts [42]. Furthermore, using an in vitro approach it was demonstrated that a dominantly inherited frameshift mutation expresses a truncated PACT protein that increases PACT mediated PKR activation causing an enhanced sensitivity to ER stress via dysregulation of the eIF2α signaling pathway [43]. Three recessively inherited (C77S, C213F, C213R) and two dominantly inherited DYT16 point mutations (N102S and T34S) also demonstrated a heightened capacity to form PACT-PACT homodimers in the absence of stress [44] and the lymphoblasts derived from DYT-PRKRA patients carrying C77S and C213R mutations showed a stronger binding affinity between PACT and PKR and a dysregulation of the ISR pathway. Consequently, these DYT-PRKRA patient lymphoblasts demonstrated an increase in cell susceptibility to ER stress that could be rescued in the presence of luteolin, which disrupts PACT-PKR interactions [62].

Figure 6. DYT-PRKRA mutations affect ISR to cause enhanced apoptosis. Normal stress response and altered stress response in DYT-PRKRA is shown. (A) ISR in wt cells. In the absence of stress, PKR is not activated as PACT is not associated with PKR. After stress, phosphorylation of PACT promotes PACT-PACT and PACT-PKR interactions causing a transient PKR activation and eIF2α phosphorylation. This transient response restores cellular homeostasis promoting survival by inducing limited amounts of activating transcription factor 4 (ATF4) and C/EBP-homologous protein (CHOP). (B) ISR in DYT-PRKRA cells. In the absence of stress, mutant PACT forms strong PACT-PACT as well as PACT-PKR interactions and PKR is activated. After stress, PACT is phosphorylated, and PACT-PACT and PACT-PKR interactions are enhanced further causing a persistent PKR activation and eIF2α phosphorylation thus promoting apoptosis.

Innate immunity and inflammation

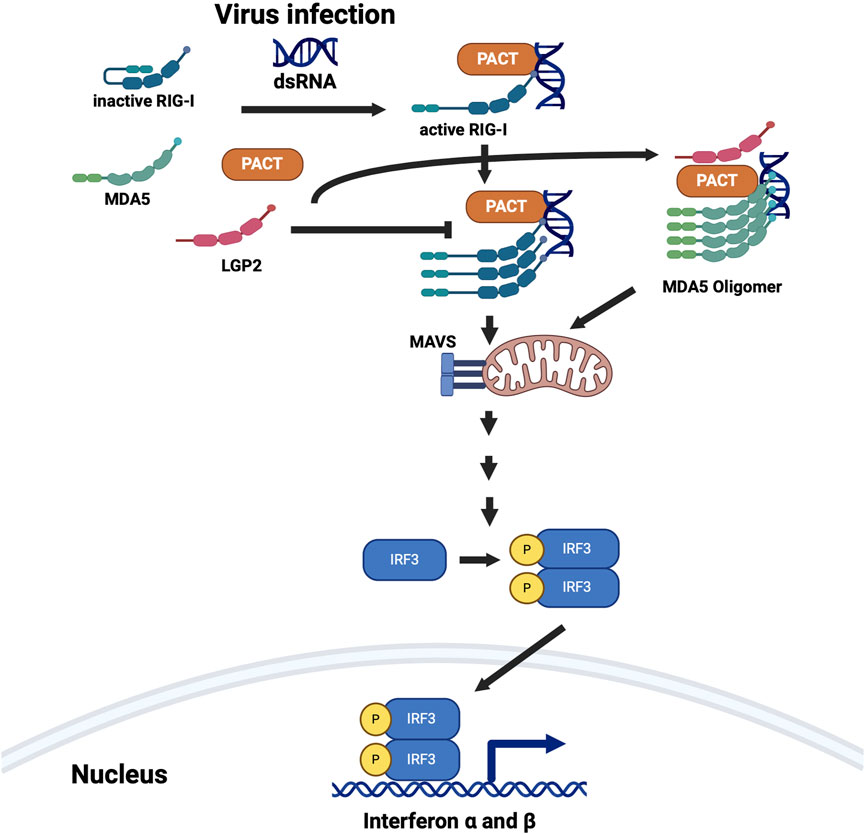

Interferons (IFNs) are antiviral cytokines that constitute a pivotal component of the body’s innate immune response against viral infections [63]. Virally infected cells produce and secrete IFNs, which prime the neighboring cells by inducing expression of hundreds of antiviral proteins even before they are infected with the virus, thus arming them with necessary defenses against a possible infection [64, 65]. The pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) present in infected cells are sensed by pattern-recognition receptors (PRRs) of the host cells [66]. The viral non-self RNAs are sensed by host PRRs such as Retinoic acid inducible gene I (RIG-I) in the cytoplasm [67], and this is a central step to induce proinflammatory and immunoregulatory response to protect the host. PACT aids RIG-I ( ) in ligand recognition and is essential to activate a robust IFN production by binding to RIG-I’s carboxy-terminal domain and stimulating its ATPase activity to expose a caspase activation and recruitment domain (CARD) motif [68]. This activated form of RIG-I interacts with the mitochondrial antiviral signaling protein (MAVS), initiating a signaling cascade that culminates in the activation of transcription factor IRF3 to cause a robust transcriptional induction of type I interferons. Additionally, PACT also functions as a coactivator of another PRR, melanoma differentiation-associated gene 5 (MDA5) by promoting MDA5 oligomerization after dsRNA-induced activation [69] to augment IFN production (Figure 7). Laboratory of genetics and physiology 2 (LGP2) is the third and least well-understood member of this PRR family. LGP2 modulates the function of RIG-I and MDA5 during viral infection in a PACT dependent manner [70].

Figure 7. PACT is involved in the interferon (IFN) production in response to dsRNA. PACT interacts with two pattern recognition receptors RIG-I (retinoic acid-inducible gene I) and MDA5 (melanoma differentiation-associated gene 5), both of which are involved in detecting dsRNA. LGP2 (laboratory of genetics and physiology 2), which inhibits RIG-I mediated IFN induction and activates MDA5 mediated IFN induction also interacts with PACT. PACT augments IFN induction via both RIG-I and MDA5 pathways but all the mechanistic details are not yet clear. Some DYT-PRKRA mutations further enhance PACT’s actions to result in higher levels of IFN production and response. Created in BioRender. Patel, R. (2025) https://BioRender.com/p51h883.

There has been a single study examining the effect of the DYT-PRKRA mutations on PACT’s ability to induce IFNs. Lymphoblasts from homozygous P222L patient as well as compound heterozygous C77S and C213R patient produced higher levels of IFN β and IFN induced genes in response to dsRNA as compared to wild type lymphoblasts [41]. Because dystonia is reported as a side effect during IFN therapy for treatment of viral infections or multiple sclerosis, it raises a possibility that DYT-PRKRA may arise from elevated levels of circulating IFNs [71, 72].Some DYT-PRKRA patients were reported to develop dystonia after a childhood febrile illness [5–9], which could have been a viral infection that may have triggered excessive or prolonged IFN production. In future, it can be tested if DYT-PRKRA patients have elevated levels of IFNs in their blood. It is relevant to also note that dystonia is one of the many symptoms Aicardi Gouetieres Syndrome (AGS), which is a rare genetic disorder classified as an interferonopathy in which a constitutive upregulation of IFN activity directly causes the disease pathology [73, 74].

RNA interference

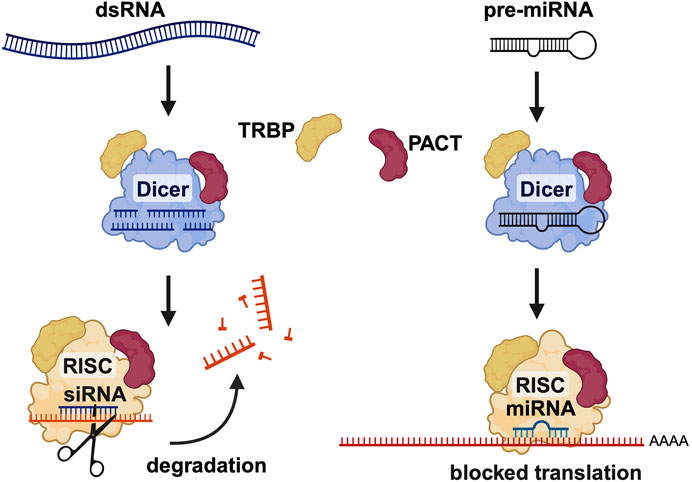

The RNA interference (RNAi) pathway is a conserved cellular mechanism crucial for gene regulation and antiviral defense [75, 76]. Triggered by double-stranded RNA (dsRNA), the pathway involves degradation or translational repression of target messenger RNA (mRNA) with the aid of small RNA molecules like microRNAs (miRNAs) and short interfering RNAs (siRNAs). These small RNA molecules guide the large, multi-subunit RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC) to the complementary mRNA sequence/s, leading to a precise control of gene expression at a post-transcriptional level in most situations. The RNAi pathway is either initiated by miRNA biogenesis [77] that leads to expression of miRNAs or processing of long dsRNAs into siRNA duplexes by the RNase Dicer [78]. The steps downstream of generation of these small RNA molecules sequentially involve loading of miRNA or siRNA guide strand into the RISC complex containing Argonaute proteins, mRNA target recognition, and cleavage of the target mRNA by Argonaute’s endo-nucleolytic activity or a block of its translation (Figure 8) [79]. Dicer, human Argonaute 2 (hAgo2), and either human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) trans-activating RNA (TAR)-binding protein (TRBP) or PACT constitute the RISC in human cells but the exact functional role of PACT in RNAi pathway is not yet clear. Recent studies suggest that although PACT is not required for the mRNA cleavage step, it is essential for the recruitment of miRNA and siRNA to the RISC [80–85]. Dicer has two Ribonuclease III (RNase III) binding domains and one dsRBM, via which it interacts with PACT’s dsRBM3 [80]. Although TRBP has been shown to affect dicer’s cleavage activity in miRNA biogenesis pathway, PACT does not directly affect Dicer activity. Dicer, PACT and TRBP form a multimeric complex and assemble even without the involvement of pre-miRNA [80]. As there has been limited research focused on elucidating PACT’s exact functional contribution to the RNAi pathway, there remains a significant scope for investigations. There have been no studies addressing the contribution of RNAi pathway to dystonia, and it remains to be determined if the dystonia causing mutations in PACT affect either a) the generation of miRNAs that are relevant in neurons or b) the function of miRNAs to modulate gene expression important for regulation of movement coordination.

Figure 8. PACT is involved in RNA interference (RNAi) pathway. PACT enhances the efficiency of SiRNA mediated RNAi and is also involved in miRNA biogenesis. PACT augments dicer activity in SiRNA generation from long dsRNAs as well as during miRNA biogenesis but the exact molecular mechanism is yet to be worked out in detail. Created in BioRender. Patel, R. (2025) https://BioRender.com/h26o315.

Murine Prkra gene and dystonia

Soon after cloning and characterization of human PACT as a PKR activator [4], the murine homolog of PACT was identified and termed RAX [16]. Human and murine proteins are highly homologous differing only in 6 amino acids, 4 of which are conservative changes [4, 16]. Like human PACT, murine PACT activates PKR by a direct interaction in response to cellular stress and regulates cellular fate [16, 28, 86]. A targeted disruption of murine Prkra gene demonstrated its functional contribution to craniofacial and postnatal pituitary development [87]. PACT null mouse had reduced size, severe microtia, hearing loss, reproductive issues, and diminished pituitary function. Surprisingly, these effects on the pituitary growth and function were dependent on activation of PKR and revealed that PACT functions as a PKR inhibitor in pituitary cells [88]. Such a role reversal of PACT’s function has also been observed in the context of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) replication [89, 90]. A missense mutation S130P in the second dsRBM of murine PACT resulted in defects in ear development, growth, craniofacial development, and ovarian structure [91]. Another study reported that deletion of the entire Prkra gene in mice is embryonic lethal at a preimplantation stage of development [92]. Interestingly, the same study also reported that Drosophila carrying a mutation in loquacious, a Prkra homolog, have a severe defect in nervous system coordination or neuromuscular function resulting in significantly reduced locomotion.

The most relevant for the topic of dystonia is a recent study of a recessively inherited spontaneously arisen frameshift mutation (Figure 9), Prkralear-5J [93]. Mice homozygous for this mutation exhibit craniofacial developmental abnormalities, reduced body size, kinked tails, and progressive dystonia with altered gait beginning at 2 weeks of age and continuing until death at about 3 weeks of age. Some neurons in the dorsal root ganglia and the trigeminal ganglion were apoptotic, consistent with the observed neurodegenerative phenotype. Basic neurological testing on mutant mice showed that the mutant mice had an elongated step/push gait, no grasping reflex with the hind paws, a weak grasping reflex with the forepaws, kinked tails and gnarled wrists. The kinked tail and gnarled wrist phenotypes were determined to result from dystonia as the bone structure of the tail and wrists was normal. The biochemical and developmental consequences of the Prkralear-5J mutation were investigated recently [94]. The truncated PACT protein produced due to the frameshift mutation retained its ability to interact with PKR, however as it lacked the dsRBM3 required for PKR activation, it inhibited PKR activation. Furthermore, mice homozygous for the mutation had abnormalities in the cerebellar development as well as a severe lack of dendritic arborization of Purkinje neurons. Reduced eIF2α phosphorylation was noted in the cerebellums and Purkinje neurons of the homozygous Prkralear-5J mice indicating that PACT mediated regulation of PKR activity and eIF2α phosphorylation plays a role in cerebellar development and may contribute to the dystonia phenotype resulting from this Prkra mutation.

Figure 9. The lear-5J frameshift mutation in the murine Prkra gene. Grey boxes: conserved dsRBM1 and dsRBM2 that facilitate high affinity dsRNA as well as protein-protein interactions. Blue box: dsRBM3 that does not bind dsRNA but has weak binding affinity to the PACT-binding motif (PBM) within the catalytic domain of PKR. The frameshift mutation from a one nucleotide insertion results in the addition of 7 novel amino acid represented in red before the stop codon.

Dysregulation of ISR and eIF2α phosphorylation in dystonia

Cellular stress response and dysregulated eIF2α phosphorylation has emerged as a major area of functional convergence [3] among various monogenic dystonia types (Figure 10). Research on DYT-PRKRA established that enhanced PKR activation and dysregulated eIF2α signaling caused increased sensitivity to apoptosis in DYT-PRKRA patient cells after endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress [42–44]. Following this initial report for DYT-PRKRA, several other dystonia types also reported dysregulated eIF2α pathway as a possible pathomechanism. DYT-TOR1A is a childhood-onset autosomal-dominant disease caused by a single amino acid deletion in the ER-resident torsinA protein. DYT-TOR1A patient cells exhibit activated ER stress response and eIF2α signaling is dysregulated [95]. Remarkably, in case of DYT-TOR1A when the eIF2α phosphorylation status was restored to normal levels, the dystonia symptoms were alleviated [96]. DYT-THAP1 is caused by mutations in THAP1 [97] and a transcriptomic analysis in neonatal mouse striatum and cerebellum indicated eIF2α signaling pathway dysregulation and the neuronal plasticity defects could be partially corrected by salubrinal, which inhibits eIF2α dephosphorylation [98]. DYT-SGCE is caused by mutations in ε-sarcoglycan (ε-SG), and PKR is upregulated in a DYT-SGCE mouse model [99]. Sporadic cervical dystonia patients have several mutations in ATF4, a downstream effector protein of the ISR response pathway [95]. Additionally, traumatic brain and spinal-cord injuries lead to injury-induced dystonia and activation of ISR and eIF2α signaling is noted in response to the injuries in animal models [100]. Finally, a growing list of dystonia genes are related to calcium physiology and may also have altered ISR and eIF2α signaling [101].

Figure 10. ER stress and eIF2α signaling dysfunction in various forms of dystonia. ER stress activates both PERK and PKR kinases that phosphorylate eIF2α, which is the central signaling hub for activating downstream pathways that can either lead to cellular recovery and homeostasis via the transcription factor ATF4 or trigger apoptosis via the transcription factor CHOP. Yellow boxes indicate various forms of dystonia that are known to affect this pathway at distinct steps. Created in BioRender. Patel, R. (2025) https://BioRender.com/y15s536.

In view of the dysregulated eIF2α phosphorylation emerging as a convergent mechanism for several dystonia types, it is crucial to characterize the changes in eIF2α phosphorylation status and ultimately the regulation of ISR in each individual form of dystonia. Both increased as well as decreased eIF2α phosphorylation has been reported in various forms of monogenic dystonia. In case of DYT-PRKRA, there is a reduction in the basal eIF2α phosphorylation levels in Prkralear-5J mice [94], which is in contrast to the increased phosphorylation of eIF2α, heightened PKR kinase activity and enhanced sensitivity to ER stress in DYT-PRKRA patient cells [42, 44]. Additionally, increase in PKR activity and eIF2α phosphorylation is reported in DYT-EIF2AK2 (DYT33) patients carrying PKR missense variants with early onset generalized dystonia [102]. For DYT-EIF2AK2 (DYT33), PKR inactivating mutations were reported in some patients [103], thereby suggesting that a reduction in PKR activity and consequently reduced eIF2α phosphorylation may also lead to dystonia pathophysiology. The most compelling evidence of reduced eIF2α phosphorylation in dystonia comes from studies on DYT-TOR1A (DYT1), where a genome-wide RNAi screen suggested a pathogenic role of deficient eIF2α signaling [95]. The HIV protease inhibitor ritonavir, which boosts eIF2α phosphorylation corrected the mutant TOR1A protein mislocalization in vitro and when administered during an early postnatal period, showed therapeutic effects in a mouse model of DYT-TOR1A, restoring brain abnormalities and ameliorating the dystonia phenotype [96]. Additionally, there is similar eIF2α pathway impairment in patients with sporadic cervical dystonia, due to rare inactivating mutations in ATF4 [95]. There are no current or past clinical trials for drugs targeting the eIF2α pathway to treat dystonia patients and in future, a few important points should be considered for conducting such trials. Although the studies on eIF2α and dystonia are encouraging for therapeutic interventions, such manipulations must be controlled carefully. Based on the available evidence, a precise regulation of the extent and duration of eIF2α phosphorylation may be essential for optimal neuronal regulation of motor control and either a reduction or elevation of the ISR response both could lead to lack of motor coordination. Thus, any future treatments that target eIF2α phosphorylation would need to be developed with caution keeping in mind not to overcorrect the underlying pathology using drugs to either boost or inhibit eIF2α phosphorylation throughout the body under all physiological scenarios. For example, it was recently reported that the cholinergic neurons constitutively engage the ISR for dopamine modulation and skill learning [104]. Such specific use of transient eIF2α phosphorylation to regulate neuronal functions will be disturbed by drugs globally targeting eIF2α pathway and thus can have detrimental off target effects.

Discussion

Although phosphorylation of eIF2α has classically been viewed as a stress response, eIF2α phosphorylation mediated regulation of protein synthesis is utilized by neurons for mechanisms besides stress response that include behavior, memory consolidation, neuronal development, and motor control [105]. Future research using targeted mutations in specific neuronal subtypes to test the exact contribution of ISR and specifically eIF2α phosphorylation for neuronal control of muscle movement will be valuable.

In addition to the characterization of molecular pathways, it is also crucial to explore the specific regions of the brain affected by dystonia. Although dystonia is considered traditionally as a disorder of the basal ganglia [106], increasing evidence suggests that other brain areas may also play a role [107–112]. In this regard, mouse models could provide important clues to understand how alterations in the eIF2α signaling can affect neuronal function in specific regions of the brain to ultimately influence coordinated muscle movements. The dysfunction of cholinergic neurons which engage the eIF2α pathway for constitutive neuronal functionality [96] is one of the convergent mechanisms in dystonia etiology [113, 114]. Future studies can address the effects of manipulating the eIF2α pathway using several drugs currently available [98, 115–118]. It is possible to either measure physiologic dynamic changes in eIF2α phosphorylation or manipulate eIF2α signaling using genetic tools in a specific subset of neurons to understand how it influences muscle movement.

Given the functional role of PACT in the RNAi pathway, it would also be valuable to examine if there are any changes in miRNA profiles in DYT-PRKRA patient cells. Although it would be most meaningful to investigate the changes in miRNA expression profiles in induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC) derived neurons from DYT-PRKRA patients, the miRNA profiles of patient lymphoblasts or fibroblasts can offer initial assessment if the DYT-PRKRA mutations can affect the miRNA biogenesis. Additionally, based on initial studies indicating the role of IFNs in DYT-PRKRA, it remains to be investigated if additional DYT-PRKRA mutations also enhance IFN production in response to dsRNA. Several DYT-PRKRA and DYT-EIF2AK2 patients developed dystonia symptoms after a febrile illness [5–9, 119], thus If DYT-PRKRA mutations lead to IFN production at higher levels or for a longer duration during viral infections, it can explain the neurologic regression and motor problems arising after a childhood illness. Based on such future studies the treatment for DYT-PRKRA can be significantly different based on the specific effects seen with various mutations, underscoring the urgency and importance of undertaking such basic mechanistic studies.

Author contributions

TS: Writing and editing; RP: Funding acquisition, supervision and editing. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This work was supported by a Department of Defense through the grant W81XWH-22-1-0526 to RP.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Author disclaimer

Opinions, conclusions and recommendations are those of the author and are not necessarily endorsed by the Department of Defense.

References

1. Jinnah, HA, and Hess, EJ. Evolving concepts in the pathogenesis of dystonia. Parkinsonism Relat Disord (2018) 46(Suppl. 1):S62–S65. doi:10.1016/j.parkreldis.2017.08.001

2. Thomsen, M, Lange, LM, Zech, M, and Lohmann, K. Genetics and pathogenesis of dystonia. Annu Rev Pathol (2024) 19:99–131. doi:10.1146/annurev-pathmechdis-051122-110756

3. Gonzalez-Latapi, P, Marotta, N, and Mencacci, NE. Emerging and converging molecular mechanisms in dystonia. J Neural Transm (Vienna) (2021) 128(4):483–98. doi:10.1007/s00702-020-02290-z

4. Patel, RC, and Sen, GC. PACT, a protein activator of the interferon-induced protein kinase. PKR EMBO J (1998) 17(15):4379–90. doi:10.1093/emboj/17.15.4379

5. Lemmon, ME, Lavenstein, B, Applegate, CD, Hamosh, A, Tekes, A, and Singer, HS. A novel presentation of DYT 16: acute onset in infancy and association with MRI abnormalities. Mov Disord (2013) 28(14):1937–8. doi:10.1002/mds.25703

6. Masnada, S, Martinelli, D, Correa-Vela, M, Agolini, E, Baide-Mairena, H, Marcé-Grau, A, et al. PRKRA-related disorders: bilateral striatal degeneration in addition to DYT16 spectrum. Mov Disord (2021) 36(4):1038–40. doi:10.1002/mds.28492

7. Bhowmick, SS, Raha, S, and Bohora, A. Early-onset dystonia, exacerbation with fever, and striatal signal changes: emerging phenotype of DYT-PRKRA. Neurology (2022) 99(5):206–7. doi:10.1212/wnl.0000000000200858

8. Pinto, MJ, Oliveira, A, Rosas, MJ, and Massano, J. Imaging evidence of nigrostriatal degeneration in DYT-PRKRA. Mov Disord Clin Pract (2020) 7(4):472–4. doi:10.1002/mdc3.12941

9. Kolbel, H, Kuechler, A, Strom, TM, Ludecke, HJ, Moller-Hartmann, C, Della-Marina, A, et al. DYT16 mimics metabolic disease with fever associated beginning of dystonia and MRI abnormalities. Eur J Pediatr Neurol (2017) 21:e177. doi:10.1016/j.ejpn.2017.04.997

10. Tisch, S, and Kumar, KR. Pallidal deep brain stimulation for monogenic dystonia: the effect of gene on outcome. Front Neurol (2020) 11:630391. doi:10.3389/fneur.2020.630391

11. Costantini, A, Trevi, E, Pala, MI, and Fancellu, R. Thiamine and dystonia 16. BMJ Case Rep (2016) 2016–2016-216721. doi:10.1136/bcr-2016-216721

12. Meurs, E, Chong, K, Galabru, J, Thomas, NS, Kerr, IM, Williams, BR, et al. Molecular cloning and characterization of the human double-stranded RNA-activated protein kinase induced by interferon. Cell (1990) 62(2):379–90. doi:10.1016/0092-8674(90)90374-n

13. Galabru, J, and Hovanessian, A. Autophosphorylation of the protein kinase dependent on double-stranded RNA. J Biol Chem (1987) 262(32):15538–44. doi:10.1016/s0021-9258(18)47759-9

14. Garcia, MA, Meurs, EF, and Esteban, M. The dsRNA protein kinase PKR: virus and cell control. Biochimie (2007) 89(6-7):799–811. doi:10.1016/j.biochi.2007.03.001

15. Patel, CV, Handy, I, Goldsmith, T, and Patel, RC. PACT, a stress-modulated cellular activator of interferon-induced double-stranded RNA-activated protein kinase. PKR J Biol Chem (2000) 275(48):37993–8. doi:10.1074/jbc.M004762200

16. Ito, T, Yang, M, and May, WS. RAX, a cellular activator for double-stranded RNA-dependent protein kinase during stress signaling. J Biol Chem (1999) 274(22):15427–32. doi:10.1074/jbc.274.22.15427

17. Singh, M, Castillo, D, Patel, CV, and Patel, RC. Stress-induced phosphorylation of PACT reduces its interaction with TRBP and leads to PKR activation. Biochemistry (2011) 50(21):4550–60. doi:10.1021/bi200104h

18. Singh, M, Fowlkes, V, Handy, I, Patel, CV, and Patel, RC. Essential role of PACT-mediated PKR activation in tunicamycin-induced apoptosis. J Mol Biol (2009) 385(2):457–68. doi:10.1016/j.jmb.2008.10.068

19. Singh, M, and Patel, RC. Increased interaction between PACT molecules in response to stress signals is required for PKR activation. J Cell Biochem (2012) 113(8):2754–64. doi:10.1002/jcb.24152

20. Patel, RC, and Sen, GC. Identification of the double-stranded RNA-binding domain of the human interferon-inducible protein kinase. J Biol Chem (1992) 267(11):7671–6. doi:10.1016/s0021-9258(18)42567-7

21. Feng, GS, Chong, K, Kumar, A, and Williams, BR. Identification of double-stranded RNA-binding domains in the interferon-induced double-stranded RNA-activated p68 kinase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. (1992) 89(12):5447–51. doi:10.1073/pnas.89.12.5447

22. Green, SR, and Mathews, MB. Two RNA-binding motifs in the double-stranded RNA-activated protein kinase, DAI. Genes Dev. (1992) 6(12B):2478–90. doi:10.1101/gad.6.12b.2478

23. Huang, X, Hutchins, B, and Patel, RC. The C-terminal, third conserved motif of the protein activator PACT plays an essential role in the activation of double-stranded-RNA-dependent protein kinase (PKR). Biochem J (2002) 366(Pt 1):175–86. doi:10.1042/BJ20020204

24. Peters, GA, Hartmann, R, Qin, J, and Sen, GC. Modular structure of PACT: distinct domains for binding and activating PKR. Mol Cell Biol (2001) 21(6):1908–20. doi:10.1128/MCB.21.6.1908-1920.2001

25. Chang, KY, and Ramos, A. The double-stranded RNA-binding motif, a versatile macromolecular docking platform. FEBS J (2005) 272(9):2109–17. doi:10.1111/j.1742-4658.2005.04652.x

26. Cole, JL. Activation of PKR: an open and shut case? Trends Biochem Sci (2007) 32(2):57–62. doi:10.1016/j.tibs.2006.12.003

27. Nanduri, S, Carpick, BW, Yang, Y, Williams, BR, and Qin, J. Structure of the double-stranded RNA-binding domain of the protein kinase PKR reveals the molecular basis of its dsRNA-mediated activation. EMBO J (1998) 17(18):5458–65. doi:10.1093/emboj/17.18.5458

28. Bennett, RL, Blalock, WL, and May, WS. Serine 18 phosphorylation of RAX, the PKR activator, is required for PKR activation and consequent translation inhibition. J Biol Chem (2004) 279(41):42687–93. doi:10.1074/jbc.M403321200

29. Peters, GA, Li, S, and Sen, GC. Phosphorylation of specific serine residues in the PKR activation domain of PACT is essential for its ability to mediate apoptosis. J Biol Chem (2006) 281(46):35129–36. doi:10.1074/jbc.M607714200

30. Daher, A, Laraki, G, Singh, M, Melendez-Pena, CE, Bannwarth, S, Peters, AH, et al. TRBP control of PACT-induced phosphorylation of protein kinase R is reversed by stress. Mol Cell Biol (2009) 29(1):254–65. doi:10.1128/MCB.01030-08

31. Camargos, S, Scholz, S, Simon-Sanchez, J, Paisan-Ruiz, C, Lewis, P, Hernandez, D, et al. DYT16, a novel young-onset dystonia-parkinsonism disorder: identification of a segregating mutation in the stress-response protein PRKRA. Lancet Neurol (2008) 7(3):207–15. doi:10.1016/S1474-4422(08)70022-X

32. Seibler, P, Djarmati, A, Langpap, B, Hagenah, J, Schmidt, A, Bruggemann, N, et al. A heterozygous frameshift mutation in PRKRA (DYT16) associated with generalised dystonia in a German patient. Lancet Neurol (2008) 7(5):380–1. doi:10.1016/S1474-4422(08)70075-9

33. Najmabadi, H, Hu, H, Garshasbi, M, Zemojtel, T, Abedini, SS, Chen, W, et al. Deep sequencing reveals 50 novel genes for recessive cognitive disorders. Nature (2011) 478(7367):57–63. doi:10.1038/nature10423

34. Camargos, S, Lees, AJ, Singleton, A, and Cardoso, F. DYT16: the original cases. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry (2012) 83(10):1012–4. doi:10.1136/jnnp-2012-302841

35. de Carvalho Aguiar, P, Borges, V, Ferraz, HB, and Ozelius, LJ. Novel compound heterozygous mutations in PRKRA cause pure dystonia. Mov Disord (2015) 30(6):877–8. doi:10.1002/mds.26175

36. Dos Santos, CO, da Silva-Junior, FP, Puga, RD, Barbosa, ER, Azevedo Silva, SMC, Borges, V, et al. The prevalence of PRKRA mutations in idiopathic dystonia. Parkinsonism Relat Disord (2018) 48:93–6. doi:10.1016/j.parkreldis.2017.12.015

37. Quadri, M, Olgiati, S, Sensi, M, Gualandi, F, Groppo, E, Rispoli, V, et al. PRKRA mutation causing early-onset generalized dystonia-parkinsonism (DYT16) in an Italian family. Mov Disord (2016) 31(5):765–7. doi:10.1002/mds.26583

38. Zech, M, Castrop, F, Schormair, B, Jochim, A, Wieland, T, Gross, N, et al. DYT16 revisited: exome sequencing identifies PRKRA mutations in a European dystonia family. Mov Disord (2014) 29(12):1504–10. doi:10.1002/mds.25981

39. Lange, LM, Junker, J, Loens, S, Baumann, H, Olschewski, L, Schaake, S, et al. Genotype-phenotype relations for isolated dystonia genes: MDSGene systematic review. Mov Disord (2021) 36(5):1086–103. doi:10.1002/mds.28485

40. Atasu, B, Simón-Sánchez, J, Hanagasi, H, Bilgic, B, Hauser, AK, Guven, G, et al. Dissecting genetic architecture of rare dystonia: genetic, molecular and clinical insights. J Med Genet (2024) 61(5):443–51. doi:10.1136/jmg-2022-109099

41. Vaughn, LS, Frederick, K, Burnett, SB, Sharma, N, Bragg, DC, Camargos, S, et al. DYT-PRKRA mutation P222L enhances PACT's stimulatory activity on type I interferon induction. Biomolecules (2022) 12(5):713. doi:10.3390/biom12050713

42. Vaughn, LS, Bragg, DC, Sharma, N, Camargos, S, Cardoso, F, and Patel, RC. Altered activation of protein kinase PKR and enhanced apoptosis in dystonia cells carrying a mutation in PKR activator protein PACT. J Biol Chem (2015) 290(37):22543–57. doi:10.1074/jbc.M115.669408

43. Burnett, SB, Vaughn, LS, Strom, JM, Francois, A, and Patel, RC. A truncated PACT protein resulting from a frameshift mutation reported in movement disorder DYT16 triggers caspase activation and apoptosis. J Cell Biochem (2019) 120(11):19004–18. doi:10.1002/jcb.29223

44. Burnett, SB, Vaughn, LS, Sharma, N, Kulkarni, R, and Patel, RC. Dystonia 16 (DYT16) mutations in PACT cause dysregulated PKR activation and eIF2α signaling leading to a compromised stress response. Neurobiol Dis (2020) 146:105135. doi:10.1016/j.nbd.2020.105135

45. Sadler, AJ, and Williams, BR. Structure and function of the protein kinase R. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol (2007) 316:253–92. doi:10.1007/978-3-540-71329-6_13

46. Brostrom, CO, Prostko, CR, Kaufman, RJ, and Brostrom, MA. Inhibition of translational initiation by activators of the glucose-regulated stress protein and heat shock protein stress response systems. Role of the interferon-inducible double-stranded RNA-activated eukaryotic initiation factor 2alpha kinase. J Biol Chem (1996) 271(40):24995–5002. doi:10.1074/jbc.271.40.24995

47. Pakos-Zebrucka, K, Koryga, I, Mnich, K, Ljujic, M, Samali, A, and Gorman, AM. The integrated stress response. EMBO Rep (2016) 17(10):1374–95. doi:10.15252/embr.201642195

48. Starck, SR, Tsai, JC, Chen, K, Shodiya, M, Wang, L, Yahiro, K, et al. Translation from the 5' untranslated region shapes the integrated stress response. Science (2016) 351(6272):aad3867. doi:10.1126/science.aad3867

49. Young, SK, and Wek, RC. Upstream open reading frames differentially regulate gene-specific translation in the integrated stress response. J Biol Chem (2016) 291(33):16927–35. doi:10.1074/jbc.R116.733899

50. Ron, D. Translational control in the endoplasmic reticulum stress response. J Clin Invest (2002) 110(10):1383–8. doi:10.1172/JCI16784

51. Andreev, DE, O'Connor, PB, Fahey, C, Kenny, EM, Terenin, IM, Dmitriev, SE, et al. Translation of 5' leaders is pervasive in genes resistant to eIF2 repression. Elife (2015) 4:e03971. doi:10.7554/eLife.03971

52. Lee, YY, Cevallos, RC, and Jan, E. An upstream open reading frame regulates translation of GADD34 during cellular stresses that induce eIF2alpha phosphorylation. J Biol Chem (2009) 284(11):6661–73. doi:10.1074/jbc.M806735200

53. Palam, LR, Baird, TD, and Wek, RC. Phosphorylation of eIF2 facilitates ribosomal bypass of an inhibitory upstream ORF to enhance CHOP translation. J Biol Chem (2011) 286(13):10939–49. doi:10.1074/jbc.M110.216093

54. Vattem, KM, Staschke, KA, and Wek, RC. Mechanism of activation of the double-stranded-RNA-dependent protein kinase, PKR: role of dimerization and cellular localization in the stimulation of PKR phosphorylation of eukaryotic initiation factor-2 (eIF2). Eur J Biochem (2001) 268(13):3674–84. doi:10.1046/j.1432-1327.2001.02273.x

55. Kojima, E, Takeuchi, A, Haneda, M, Yagi, A, Hasegawa, T, Yamaki, K, et al. The function of GADD34 is a recovery from a shutoff of protein synthesis induced by ER stress: elucidation by GADD34-deficient mice. FASEB J (2003) 17(11):1573–5. doi:10.1096/fj.02-1184fje

56. Ma, Y, and Hendershot, LM. Delineation of a negative feedback regulatory loop that controls protein translation during endoplasmic reticulum stress. J Biol Chem (2003) 278(37):34864–73. doi:10.1074/jbc.M301107200

57. Galehdar, Z, Swan, P, Fuerth, B, Callaghan, SM, Park, DS, and Cregan, SP. Neuronal apoptosis induced by endoplasmic reticulum stress is regulated by ATF4-CHOP-mediated induction of the Bcl-2 homology 3-only member PUMA. J Neurosci (2010) 30(50):16938–48. doi:10.1523/jneurosci.1598-10.2010

58. Li, Y, Guo, Y, Tang, J, Jiang, J, and Chen, Z. New insights into the roles of CHOP-induced apoptosis in ER stress. Acta Biochim Biophys Sin (Shanghai) (2014) 46(8):629–40. doi:10.1093/abbs/gmu048

59. Marciniak, SJ, and Ron, D. Endoplasmic reticulum stress signaling in disease. Physiol Rev (2006) 86(4):1133–49. doi:10.1152/physrev.00015.2006

60. Sen, GC, and Peters, GA. Viral stress-inducible genes. Adv Virus Res (2007) 70:233–63. doi:10.1016/S0065-3527(07)70006-4

61. Williams, BR. Signal integration via PKR. Sci STKE (2001) 2001(89):RE2. doi:10.1126/stke.2001.89.re2

62. Frederick, K, and Patel, RC. Luteolin protects DYT-PRKRA cells from apoptosis by suppressing PKR activation. Front Pharmacol (2023) 14:1118725. doi:10.3389/fphar.2023.1118725

63. Dalskov, L, Gad, HH, and Hartmann, R. Viral recognition and the antiviral interferon response. EMBO J (2023) 42(14):e112907. doi:10.15252/embj.2022112907

64. Ivashkiv, LB, and Donlin, LT. Regulation of type I interferon responses. Nat Rev Immunol (2014) 14(1):36–49. doi:10.1038/nri3581

65. Babadei, O, Strobl, B, Müller, M, and Decker, T. Transcriptional control of interferon-stimulated genes. J Biol Chem (2024) 300(10):107771. doi:10.1016/j.jbc.2024.107771

66. Gewaid, H, and Bowie, AG. Regulation of type I and type III interferon induction in response to pathogen sensing. Curr Opin Immunol (2024) 87:102424. doi:10.1016/j.coi.2024.102424

67. Yoneyama, M, Kikuchi, M, Natsukawa, T, Shinobu, N, Imaizumi, T, Miyagishi, M, et al. The RNA helicase RIG-I has an essential function in double-stranded RNA-induced innate antiviral responses. Nat Immunol (2004) 5(7):730–7. doi:10.1038/ni1087

68. Kok, KH, Lui, PY, Ng, MH, Siu, KL, Au, SW, and Jin, DY. The double-stranded RNA-binding protein PACT functions as a cellular activator of RIG-I to facilitate innate antiviral response. Cell Host Microbe (2011) 9(4):299–309. doi:10.1016/j.chom.2011.03.007

69. Lui, PY, Wong, LR, Ho, TH, Au, SWN, Chan, CP, Kok, KH, et al. PACT facilitates RNA-induced activation of MDA5 by promoting MDA5 oligomerization. J Immunol (2017) 199(5):1846–55. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.1601493

70. Sanchez David, RY, Combredet, C, Najburg, V, Millot, GA, Beauclair, G, Schwikowski, B, et al. LGP2 binds to PACT to regulate RIG-I- and MDA5-mediated antiviral responses. Sci Signal (2019) 12(601):eaar3993. doi:10.1126/scisignal.aar3993

71. Atasoy, N, Ustundag, Y, Konuk, N, and Atik, L. Acute dystonia during pegylated interferon alpha therapy in a case with chronic hepatitis B infection. Clin Neuropharmacol (2004) 27(3):105–7. doi:10.1097/00002826-200405000-00002

72. Quarantini, LC, Miranda-Scippa, A, Parana, R, Sampaio, AS, and Bressan, RA. Acute dystonia after injection of pegylated interferon alpha-2b. Mov Disord (2007) 22(5):747–8. doi:10.1002/mds.21302

73. Rice, GI, Kasher, PR, Forte, GM, Mannion, NM, Greenwood, SM, Szynkiewicz, M, et al. Mutations in ADAR1 cause Aicardi-Goutieres syndrome associated with a type I interferon signature. Nat Genet (2012) 44(11):1243–8. doi:10.1038/ng.2414

74. Livingston, JH, Lin, JP, Dale, RC, Gill, D, Brogan, P, Munnich, A, et al. A type I interferon signature identifies bilateral striatal necrosis due to mutations in ADAR1. J Med Genet (2014) 51(2):76–82. doi:10.1136/jmedgenet-2013-102038

75. Wilson, RC, and Doudna, JA. Molecular mechanisms of RNA interference. Annu Rev Biophys (2013) 42:217–39. doi:10.1146/annurev-biophys-083012-130404

76. Jinek, M, and Doudna, JA. A three-dimensional view of the molecular machinery of RNA interference. Nature (2009) 457(7228):405–12. doi:10.1038/nature07755

77. Shang, R, Lee, S, Senavirathne, G, and Lai, EC. microRNAs in action: biogenesis, function and regulation. Nat Rev Genet (2023) 24(12):816–33. doi:10.1038/s41576-023-00611-y

78. Zapletal, D, Kubicek, K, Svoboda, P, and Stefl, R. Dicer structure and function: conserved and evolving features. EMBO Rep (2023) 24(7):e57215. doi:10.15252/embr.202357215

79. Olina, AV, Kulbachinskiy, AV, Aravin, AA, and Esyunina, DM. Argonaute proteins and mechanisms of RNA interference in eukaryotes and prokaryotes. Biochemistry (Mosc). (2018) 83(5):483–97. doi:10.1134/s0006297918050024

80. Lee, Y, Hur, I, Park, SY, Kim, YK, Suh, MR, and Kim, VN. The role of PACT in the RNA silencing pathway. EMBO J (2006) 25(3):522–32. doi:10.1038/sj.emboj.7600942

81. Noland, CL, and Doudna, JA. Multiple sensors ensure guide strand selection in human RNAi pathways. RNA (2013) 19(5):639–48. doi:10.1261/rna.037424.112

82. Takahashi, T, Miyakawa, T, Zenno, S, Nishi, K, Tanokura, M, and Ui-Tei, K. Distinguishable in vitro binding mode of monomeric TRBP and dimeric PACT with siRNA. PLoS One (2013) 8(5):e63434. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0063434

83. Lee, HY, Zhou, K, Smith, AM, Noland, CL, and Doudna, JA. Differential roles of human Dicer-binding proteins TRBP and PACT in small RNA processing. Nucleic Acids Res (2013) 41(13):6568–76. doi:10.1093/nar/gkt361

84. Wilson, RC, Tambe, A, Kidwell, MA, Noland, CL, Schneider, CP, and Doudna, JA. Dicer-TRBP complex formation ensures accurate mammalian MicroRNA biogenesis. Mol Cell (2015) 57(3):397–407. doi:10.1016/j.molcel.2014.11.030

85. Heyam, A, Lagos, D, and Plevin, M. Dissecting the roles of TRBP and PACT in double-stranded RNA recognition and processing of noncoding RNAs. Wiley Interdiscip Rev RNA (2015) 6(3):271–89. doi:10.1002/wrna.1272

86. Bennett, RL, Blalock, WL, Abtahi, DM, Pan, Y, Moyer, SA, and May, WS. RAX, the PKR activator, sensitizes cells to inflammatory cytokines, serum withdrawal, chemotherapy, and viral infection. Blood (2006) 108(3):821–9. doi:10.1182/blood-2005-11-006817

87. Rowe, TM, Rizzi, M, Hirose, K, Peters, GA, and Sen, GC. A role of the double-stranded RNA-binding protein PACT in mouse ear development and hearing. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. (2006) 103(15):5823–8. doi:10.1073/pnas.0601287103

88. Dickerman, BK, White, CL, Kessler, PM, Sadler, AJ, Williams, BR, and Sen, GC. The protein activator of protein kinase R, PACT/RAX, negatively regulates protein kinase R during mouse anterior pituitary development. FEBS J (2015) 282(24):4766–81. doi:10.1111/febs.13533

89. Clerzius, G, Shaw, E, Daher, A, Burugu, S, Gelinas, JF, Ear, T, et al. The PKR activator, PACT, becomes a PKR inhibitor during HIV-1 replication. Retrovirology (2013) 10:96. doi:10.1186/1742-4690-10-96

90. Chukwurah, E, Handy, I, and Patel, RC. ADAR1 and PACT contribute to efficient translation of transcripts containing HIV-1 trans-activating response (TAR) element. Biochem J (2017) 474(7):1241–57. doi:10.1042/bcj20160964

91. Dickerman, BK, White, CL, Chevalier, C, Nalesso, V, Charles, C, Fouchecourt, S, et al. Missense mutation in the second RNA binding domain reveals a role for Prkra (PACT/RAX) during skull development. PLoS One (2011) 6(12):e28537. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0028537

92. Bennett, RL, Blalock, WL, Choi, EJ, Lee, YJ, Zhang, Y, Zhou, L, et al. RAX is required for fly neuronal development and mouse embryogenesis. Mech Dev (2008) 125(9-10):777–85. doi:10.1016/j.mod.2008.06.009

93. Palmer, K, Fairfield, H, Borgeia, S, Curtain, M, Hassan, MG, Dionne, L, et al. Discovery and characterization of spontaneous mouse models of craniofacial dysmorphology. Dev Biol (2016) 415(2):216–27. doi:10.1016/j.ydbio.2015.07.023

94. Burnett, SB, Culver, AM, Simon, TA, Rowson, T, Frederick, K, Palmer, K, et al. Mutation in Prkra results in cerebellar abnormality and reduced eIF2α phosphorylation in a model of DYT-PRKRA. Dis Model Mech (2024) 17(11):dmm050929. doi:10.1242/dmm.050929

95. Rittiner, JE, Caffall, ZF, Hernandez-Martinez, R, Sanderson, SM, Pearson, JL, Tsukayama, KK, et al. Functional genomic analyses of mendelian and sporadic disease identify impaired eIF2alpha signaling as a generalizable mechanism for dystonia. Neuron (2016) 92(6):1238–51. doi:10.1016/j.neuron.2016.11.012

96. Caffall, ZF, Wilkes, BJ, Hernández-Martinez, R, Rittiner, JE, Fox, JT, Wan, KK, et al. The HIV protease inhibitor, ritonavir, corrects diverse brain phenotypes across development in mouse model of DYT-TOR1A dystonia. Sci Transl Med (2021) 13(607):eabd3904. doi:10.1126/scitranslmed.abd3904

97. Zakirova, Z, Fanutza, T, Bonet, J, Readhead, B, Zhang, W, Yi, Z, et al. Mutations in THAP1/DYT6 reveal that diverse dystonia genes disrupt similar neuronal pathways and functions. PLoS Genet (2018) 14(1):e1007169. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1007169

98. Boyce, M, Bryant, KF, Jousse, C, Long, K, Harding, HP, Scheuner, D, et al. A selective inhibitor of eIF2alpha dephosphorylation protects cells from ER stress. Science (2005) 307(5711):935–9. doi:10.1126/science.1101902

99. Xiao, J, Vemula, SR, Xue, Y, Khan, MM, Carlisle, FA, Waite, AJ, et al. Role of major and brain-specific Sgce isoforms in the pathogenesis of myoclonus-dystonia syndrome. Neurobiol Dis (2017) 98:52–65. doi:10.1016/j.nbd.2016.11.003

100. Chou, A, Krukowski, K, Jopson, T, Zhu, PJ, Costa-Mattioli, M, Walter, P, et al. Inhibition of the integrated stress response reverses cognitive deficits after traumatic brain injury. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A (2017) 114(31):E6420-E6426–e6. doi:10.1073/pnas.1707661114

101. Jinnah, HA, and Sun, YV. Dystonia genes and their biological pathways. Neurobiol Dis (2019) 129:159–68. doi:10.1016/j.nbd.2019.05.014

102. Kuipers, DJS, Mandemakers, W, Lu, CS, Olgiati, S, Breedveld, GJ, Fevga, C, et al. EIF2AK2 missense variants associated with early onset generalized dystonia. Ann Neurol (2021) 89(3):485–97. doi:10.1002/ana.25973

103. Mao, D, Reuter, CM, Ruzhnikov, MRZ, Beck, AE, Farrow, EG, Emrick, LT, et al. De novo EIF2AK1 and EIF2AK2 variants are associated with developmental delay, leukoencephalopathy, and neurologic decompensation. Am J Hum Genet (2020) 106(4):570–83. doi:10.1016/j.ajhg.2020.02.016

104. Helseth, AR, Hernandez-Martinez, R, Hall, VL, Oliver, ML, Turner, BD, Caffall, ZF, et al. Cholinergic neurons constitutively engage the ISR for dopamine modulation and skill learning in mice. Science (2021) 372(6540):eabe1931. doi:10.1126/science.abe1931

105. Bellato, HM, and Hajj, GN. Translational control by eIF2α in neurons: beyond the stress response. Cytoskeleton (Hoboken) (2016) 73(10):551–65. doi:10.1002/cm.21294

106. Mink, JW. The Basal Ganglia and involuntary movements: impaired inhibition of competing motor patterns. Arch Neurol (2003) 60(10):1365–8. doi:10.1001/archneur.60.10.1365

107. Jinnah, HA, Neychev, V, and Hess, EJ. The anatomical basis for dystonia: the motor network model. Tremor Other Hyperkinet Mov (N Y) (2017) 7:506. doi:10.7916/D8V69X3S

108. Shakkottai, VG, Batla, A, Bhatia, K, Dauer, WT, Dresel, C, Niethammer, M, et al. Current opinions and areas of consensus on the role of the cerebellum in dystonia. Cerebellum (2017) 16(2):577–94. doi:10.1007/s12311-016-0825-6

109. Prudente, CN, Hess, EJ, and Jinnah, HA. Dystonia as a network disorder: what is the role of the cerebellum? Neuroscience (2014) 260:23–35. doi:10.1016/j.neuroscience.2013.11.062

110. Neychev, VK, Fan, X, Mitev, VI, Hess, EJ, and Jinnah, HA. The basal ganglia and cerebellum interact in the expression of dystonic movement. Brain (2008) 131(Pt 9):2499–509. doi:10.1093/brain/awn168

111. Mahajan, A, Gupta, P, Jacobs, J, Marsili, L, Sturchio, A, Jinnah, HA, et al. Impaired saccade adaptation in tremor-dominant cervical dystonia-evidence for maladaptive cerebellum. Cerebellum (2021) 20(5):678–86. doi:10.1007/s12311-020-01104-y

112. Brown, AM, van der Heijden, ME, Jinnah, HA, and Sillitoe, RV. Cerebellar dysfunction as a source of dystonic phenotypes in mice. Cerebellum (2023) 22(4):719–29. doi:10.1007/s12311-022-01441-0

113. Eskow Jaunarajs, KL, Scarduzio, M, Ehrlich, ME, McMahon, LL, and Standaert, DG. Diverse mechanisms lead to common dysfunction of striatal cholinergic interneurons in distinct genetic mouse models of dystonia. J Neurosci (2019) 39(36):7195–205. doi:10.1523/jneurosci.0407-19.2019

114. Eskow Jaunarajs, KL, Bonsi, P, Chesselet, MF, Standaert, DG, and Pisani, A. Striatal cholinergic dysfunction as a unifying theme in the pathophysiology of dystonia. Prog Neurobiol (2015) 127-128:91–107. doi:10.1016/j.pneurobio.2015.02.002

115. Sidrauski, C, McGeachy, AM, Ingolia, NT, and Walter, P. The small molecule ISRIB reverses the effects of eIF2α phosphorylation on translation and stress granule assembly. Elife (2015) 4:e05033. doi:10.7554/eLife.05033

116. Sekine, Y, Zyryanova, A, Crespillo-Casado, A, Fischer, PM, Harding, HP, and Ron, D. Stress responses. Mutations in a translation initiation factor identify the target of a memory-enhancing compound. Science (2015) 348(6238):1027–30. doi:10.1126/science.aaa6986

117. Carrara, M, Sigurdardottir, A, and Bertolotti, A. Decoding the selectivity of eIF2alpha holophosphatases and PPP1R15A inhibitors. Nat Struct Mol Biol (2017) 24(9):708–16. doi:10.1038/nsmb.3443

118. Fullwood, MJ, Zhou, W, and Shenolikar, S. Targeting phosphorylation of eukaryotic initiation factor-2α to treat human disease. Prog Mol Biol Transl Sci (2012) 106:75–106. doi:10.1016/b978-0-12-396456-4.00005-5

119. Waller, SE, Morales-Briceño, H, Williams, L, Mohammad, SS, Fellner, A, Kumar, KR, et al. Possible EIF2AK2-associated stress-related neurological decompensation with combined dystonia and striatal lesions. Mov Disord Clin Pract (2022) 9(2):240–4. doi:10.1002/mdc3.13384

Glossary

DYT dystonia

PRKRA protein activator of interferon induced protein kinase EIF2AK2

EIF2AK2 eIF2 alpha kinase 2

EIF2Α alpha subunit of eukaryotic initiation factor 2

PKR protein kinase, RNA activated

PACT protein activator of PKR

dsRNA double-stranded RNA

dsRBM dsRNA-binding motif

PBM PACT-binding motif

GPi globus pallidus internus

DBS deep brain stimulation

ER endoplasmic reticulum

ISR integrated stress response

uORF upstream open reding frame

UTR untranslated region

ATF4 activating transcription factor 4

CHOP CEBP homologous protein

GADD34 growth arrest DNA damage-inducible 34

PARP1 poly ADP ribose polymerase 1

IFN interferon

PAMPs pathogen-associated molecular patterns

PRRs pattern-recognition receptors

RIG-I retinoic acid inducible gene I

CARD caspase activation and recruitment domain

MAVS mitochondrial antiviral signaling protein

IRF3 interferon regulated factor 3

MDA5 melanoma differentiation-associated gene 5

LGP2 laboratory of genetics and physiology 2

AGS Aicardi Gouetieres Syndrome

RNAi RNA interference

miRNA micoRNA

siRNA short interfering RNA

RISC RNA-induced silencing complex

hAgo2 Human Argonaute 2

TRBP human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) trans-activating RNA (TAR)-binding protein

RNase III Ribonuclease III

iPSC induced pluripotent stem cell

Keywords: dystonia, DYT-PRKRA, PACT, PKR, PRKRA, EIF2AK2, eIF2alpha, interferon

Citation: Simon TA and Patel RC (2025) Molecular mechanisms in DYT-PRKRA: pathways regulated by PKR activator protein PACT. Dystonia 4:14224. doi: 10.3389/dyst.2025.14224

Received: 18 December 2024; Accepted: 28 February 2025;

Published: 13 March 2025.

Edited by:

Aasef Shaikh, Case Western Reserve University, United StatesCopyright © 2025 Simon and Patel. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Rekha C. Patel, cGF0ZWxyQGJpb2wuc2MuZWR1

Tricia A. Simon

Tricia A. Simon Rekha C. Patel

Rekha C. Patel