Abstract

Today, many churches all around the world are in various states of disrepair, which would be an irreparable loss. This research paper examines the new, mixed or extended adaptive use of underutilised and abandoned ecclesiastical cultural heritage with specific reference to human-centred impact analysis and the creation of added value. Sixty-five (65) international case studies are analysed to explore creative holistic solutions to re-integrating underutilised and disused religious assets back into contemporary urban and rural landscapes. The case study analysis encompasses: ecclesiastical stakeholder valorisation; forms of obsolescence; dimensions of adaptability; interpretation of complex value relationships and human-centred impact analysis. The case study findings indicate that sensitive adaptive reuse of obsolete religious structures to Post Religious Uses has the potential to encourage positive inflows of investment capital with corresponding positive impacts on the economic values attached to new and extended uses in addition to spiritual, cultural, social, environmental and economic values for society. The research proves that churches which are brought back into the contemporary urban fabric of communities has the potential to yield benefits that contribute to sustainable development and contribute to cultural capital.

Introduction

Ecclesiastical heritage forms a distinctive visual keystone to urban and rural landscapes in addition to encompassing complex multi-faceted spiritual, cultural, aesthetic, social, environmental and economic values. Falling numbers of active religious worshipers have resulted in large numbers of heritage assets falling out of their original spiritual use and thus falling prey to negative value judgements by society.

This paper relates to immovable ecclesiastical historic structures and ensembles encompassing both tangible and intangible cultural heritage values, which cannot be replaced once the structures are destroyed—including destruction by neglect. Sixty-five international ecclesiastical case studies are examined to explore creative holistic solutions to re-integrating underutilised and disused religious assets back into contemporary urban and rural landscapes, when adaptive reuse is considered an essential strategy for the sustainability of cultural heritage, and furthermore for preserving the image of the city (Dogan, 2019). Case study analysis encompasses: ecclesiastical valorisation; forms of obsolescence (pre-adaptation); dimensions of adaptability; impact analysis and interpretation of complex value relationships.

This analysis and dialogue on possible new forms of use for religious heritage is mindful of the necessity to respect and protect diverse cultural beliefs and the collective memories of past, present and future communities—worshipers and non-worshipers alike (Sedova, 2020). In this regard, it is important to acknowledge that creative adaptive reuse solutions for ecclesiastical heritage assets are not always directly transferable between regions and cultures due to differing traditional spiritual beliefs and value systems (Pickerill et al., 2009).

Literature review

Underutilised and abandoned religious heritage assets provide an unprecedented opportunity for local communities to benefit from “human-centred” (EU, 2020) strategic development approaches. According to the European Commission, a “human-centred” city is a city “that is well-assembled, where there is history, character, distinctiveness, diversity and vitality, with high levels of liveability and all the necessary support facilities, from health and education to culture and public spaces. All of these generate a rich civic life” (EU, 2020, p. 16). Thus, “human-centred” impact analysis is the one which is based on the recognition of history, character, distinctiveness, diversity and vitality. The history is the first aspect which is used to describe the “human-centred” city concept. The Leeuwarden Declaration makes specific reference to religious sites’ history (including religious sites located in cities but not limited to) and explores the multiple benefits of finding “new, mixed or extended use” for underutilised and abandoned heritage sites that have lost their traditional function in society (ACE, 2018).

In general terms, “Adaptation” can be defined as any work done to a building, over and above maintenance, to change its spaces, tasks, capacity, function, or performance, in other words, any interventions to adjust, reuse, or upgrade a building to suit new conditions or requirements (Douglas, 2006; Wilkinson et al., 2014). In the context of this research, Foster (2020) provides a definition of cultural heritage adaptive reuse projects as the retrofit, rehabilitation and redevelopment of one or more buildings that reflects the changing needs of communities. Tying in with the circular economy approach, adaptive reuse provides a strategy aimed at preserving cultural, social, economic and environmental values, while at the same time adapting obsolete built heritage for new, extended and shared uses.

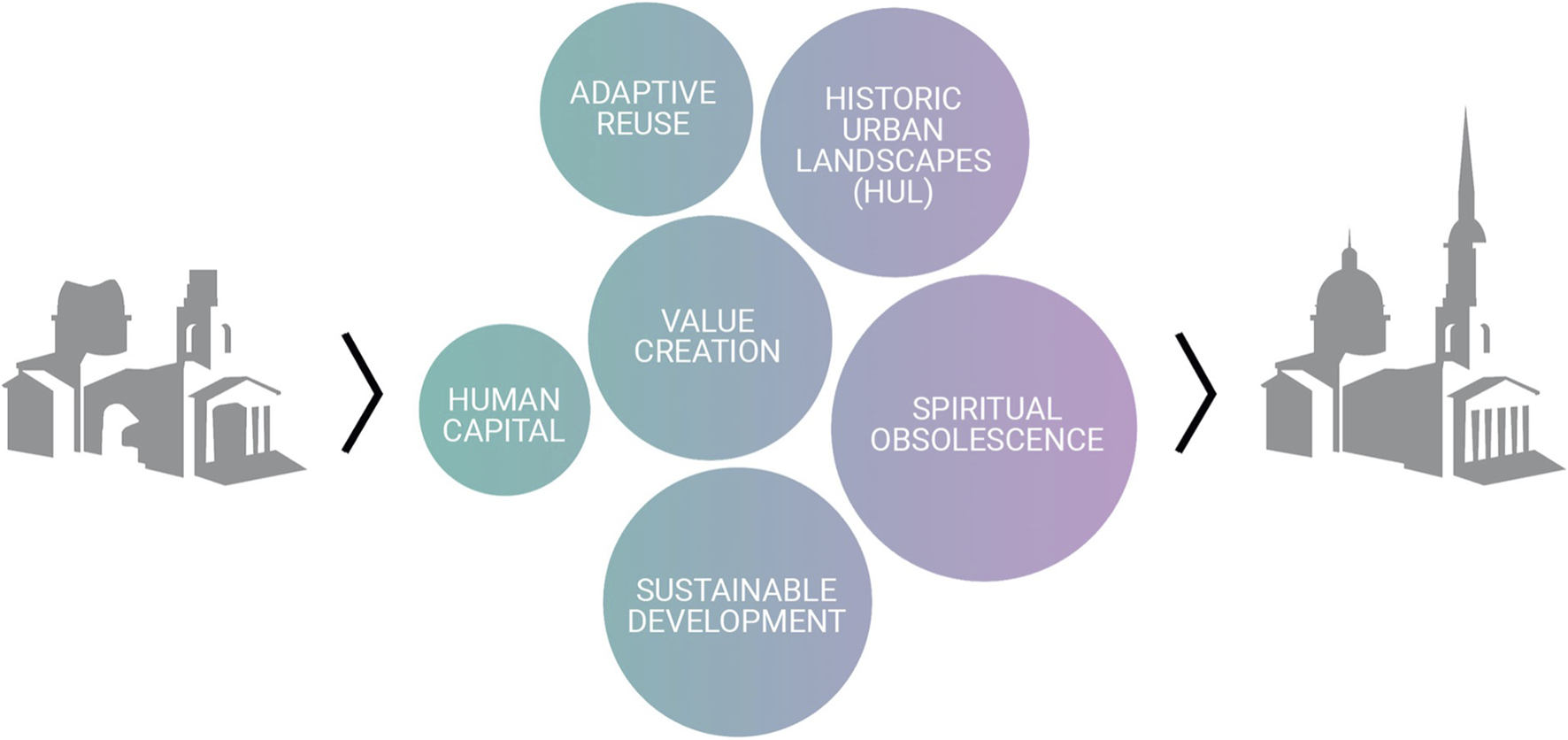

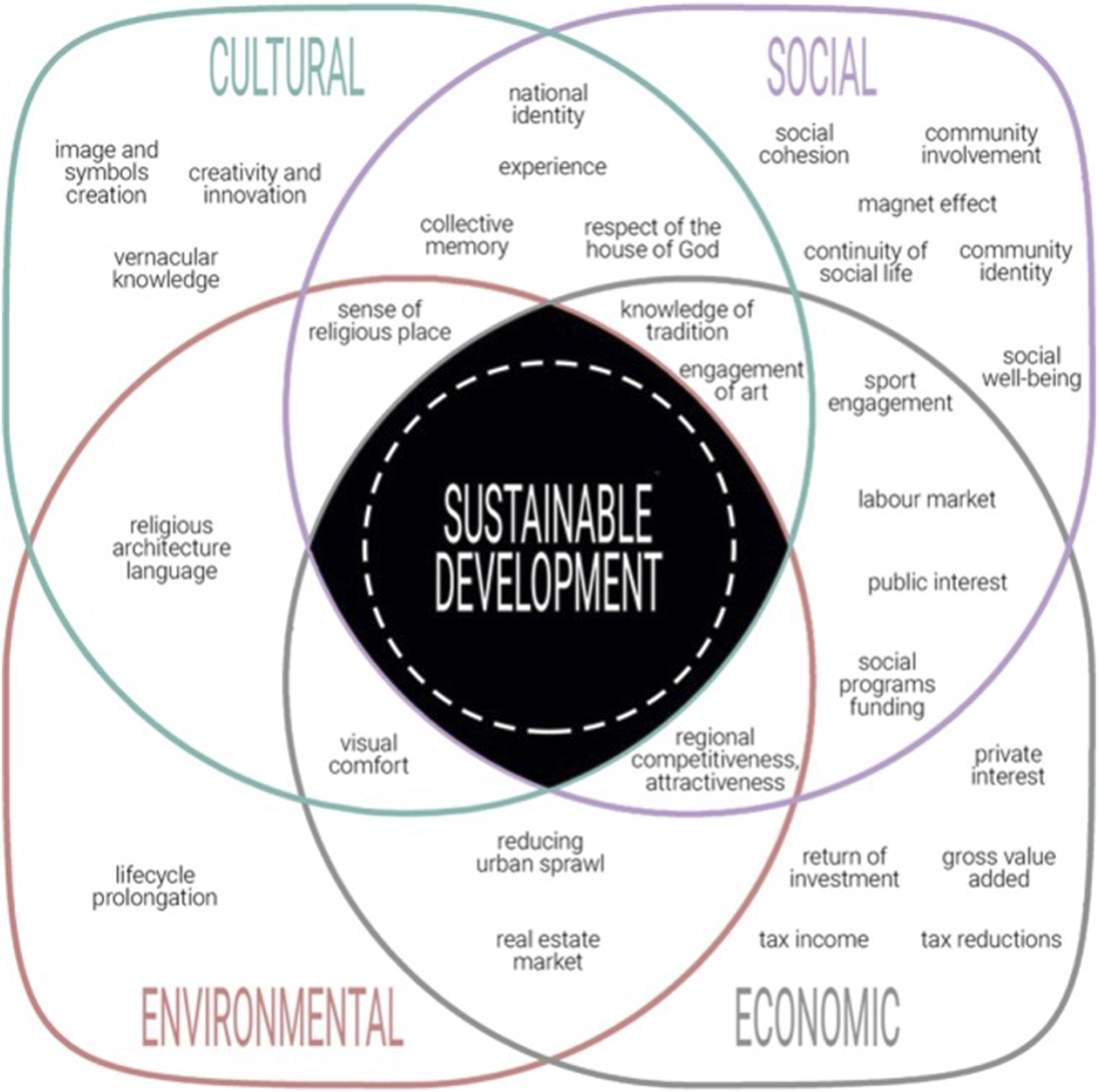

This initial theoretical perspective lays the groundwork for the practical case study analysis to highlight potential new, mixed or extended uses of ecclesiastical cultural heritage through adaptive reuse and further clarify possible relationships between the above components within a sustainable circular economy development strategy (see Figure 1). The Author argues that the study of such topics as “human capital,” “adaptive reuse,” “value creation,” “sustainable development,” “historic urban landscapes (HUL),” and “spiritual obsolescence” builds a bridge between the obsolete historic religious cultural heritage and the prosperous one. All these topics build up adaptive reuse, which therefore contributes to circular economy.

FIGURE 1

Key words of the study. Source: Own.

Holistic management and valorisation of ecclesiastical cultural heritage

With regard to religious cultural heritage, the Second Conference on Human Settlements (Habitat ll) expresses the sentiment that historical places, objects and manifestations of cultural, scientific, symbolic, spiritual and religious value are important expressions of the culture, identity and religious beliefs of societies. Their role and importance, particularly in the light of the need for cultural identity and continuity in a rapidly changing world, need to be promoted (United Nations, 1996).

The Leeuwarden Declaration states that heritage buildings, including ecclesiastic heritage, that have lost their original function, still embody cultural, historic, spatial and economic values. Through adaptation, obsolete religious heritage can find new, mixed or extended uses. As a result, their social, environmental and economic value is increased, while their cultural significance is enhanced. As such, the Leeuwarden Declaration refers to the beneficial impacts of adaptive reuse based on the four pillars: social, environmental, economic, and cultural; but, more importantly, it stresses the strong spiritual values of religious sites, which have lost the functions for which they were originally built (ACE, 2018).

Value formation in spiritual context

Based on the information from

Throsby (2012),

UNESCO (2013),

CHCfE (2015), and

Foster (2020), this research divides ecclesiastic heritage values into four categories: Cultural, Social, Environmental and Economic:

•Cultural Value incorporates inter-related, multi-dimensional values, where significance may vary depending on the particular ecclesiastical cultural heritage asset and human value judgements placed on it by society.

•Spiritual Value is associated with the sense of identity of local communities and memory of our ancestors. Mason (2002, p. 12) states that spiritual values “encompass a secular experience of wonder, awe, which can be provoked by visiting ecclesiastic heritage places.” Throsby (2012) refers to intercultural understanding inspired by different communities recognising shared spiritual values.

•Emotional Value is associated with feelings of happiness, pride or agony of believers and parishioners. These emotions are rooted in the “Collective Memory” of the community, in the culture of worshiping, and symbolic reminder of important life events such as christenings, weddings and funerals (Sedova, 2020). Such collective values that people attach to the historic environment are a valid justification for preservation laws (Wells and Lixinski, 2016).

•Historical and Aesthetic Values exist where a religious building, or ensemble, possesses beauty in itself or in its current and past relationship to the surrounding landscape. Historical values also relate to identity and use of traditional building methods and vernacular structural materials, which have sustained for many centuries and therefore represent connection with and the knowledge of past generations.

•Architectural and Symbolic Values, where the symbolic value of ecclesiastical architecture is often highlighted by distinctive landmark locations together with ornate ecclesiastic interior architectural decoration, furniture and icons which embody faith and pride in the presence of a higher order.

•Political Value is defined by Mason (2002, p. 11) as “the use of heritage to build or sustain civil relations, governmental legitimacy, protest, or ideological causes.” Political intervention in religious affairs can also be devastating due to social and cultural intolerance and hostility.

•Social Value stems from social connections, relationships and shared beliefs that exist due to the religious use of the ecclesiastic heritage, namely performing church services and celebrations, christenings, wedding ceremonies, funerals. Social value is based on community identity and the “Collective Memory” of individuals, which creates social cohesion and stability that has the potential to sustain even if a church function becomes redundant.

•Environmental Value is established via environmental impact assessment of ecclesiastic heritage on environmental sustainability.

•Economic Value stems from demand and supply in the marketplace and is influenced by location-specific existing use values, in addition to potential adaptive reuse or redevelopment values i.e., Hope Value (Pickerill, 2009). Wilkinson, Remoy and Langston (2014) observe that obsolete objects of cultural heritage have low market values based on their underutilised value in use.

Diverse values of religious cultural heritage establish a framework when owners, occupiers, worshipers, local communities, developers, financiers, sponsors and voluntary bodies will experience a different perception of the costs and benefits of adaptation, thus creating diversity in the decision-making process. The European Declaration on Cultural Diversity (COE, 2000) and the Universal Declaration on Cultural Diversity (UNESCO, 2001) recognise that respect for cultural diversity is an essential condition of human society. Successful adaptation efforts to protect the historic religious fabric have to recognise and reconcile divergent value systems and conflicting interests of stakeholders. Collaborative approaches in decision making with regard to the future reuse of abandoned religious assets can contribute to building up “Institutional Capacity” by addressing the reality of conflict of interest between stakeholders in non-combative ways.

Stakeholder value judgements in spiritual context

Within value assessment as a process, it is suggested that the evaluation of information happens through a participatory process by bringing together all stakeholders’ opinions to formulate statements of significance (Gallou and Fouseki, 2019). As such, reuse decisions regarding abandoned ecclesiastical heritage are influenced by value judgements of a diverse range of stakeholders (Sedova, 2020). Capital expenditure on cultural heritage investment projects, such as preventive maintenance, conservation, upgrading or adaptive reuse is often subjected to standard market-driven, risk averse, investment appraisal techniques (Throsby, 2012) (Pickerill, 2009; Pickerill, 2015). The Nara Document on Authenticity explores the idea that it is not wise to base value judgements within rigid set criteria, as recognition of authentic cultural heritage “may differ from culture to culture, and even within the same culture” (ICOMOS, 1994, S.11). Hutter and Rizzo (1997) refer to cultural heritage as “nomadic” due to ever changing values and social norms through time and across groups. Pignataro and Rizzo (1997) assert that the strength of regulatory control directly impacts the investment costs associated with adaptation, maintenance and ongoing restricted use. As private sector investors and developers seek to maximise profit levels, there is an inevitable danger that socio-cultural values will be sacrificed to minimise costs in order to enhance commercial values. Misguided profit orientation will deprive historic monuments with a strictly cultural (and by association spiritual) function of their integrity and intrinsic attractiveness.

Ecclesiastical impact assessment

Impact analysis can be used as a prerequisite for ecclesiastical adaptive reuse project evaluation where impacts can be translated into potential direct and indirect costs and benefits.

Landry et al. (1993)defines “Impact” as a dynamic concept which presupposes a relationship of cause and effect that can be measured through the evaluation of the outcomes of particular actions, suggesting that an impact is the power to produce change.

Ost and Van (1998)identify two forms of analysis aimed at identifying actions, perceptions or attitudes in the context of cultural built heritage. Both methods utilise a description of economic flows in the impact area, identification of direct and indirect effects and a differentiation of stakeholders.

• Impact Analysis (a non-decision-making process) encompassing analysis of the costs and benefits generated by the presence and/or utilisation of cultural built heritage in its current state.

• Project Evaluation (a decision-making process) encompassing analysis of the costs and benefits that will eventually be generated by some form of physical intervention over a period of time.

CHCfE (2015) proposes a holistic framework approach, utilising four interrelated impact domains (social, cultural, economic and environmental), to highlight the relationship between value and impact in the context of cultural heritage. This four-pillar framework approach is based on the proviso that the assessment of value and the decision to undertake heritage activities are dependent on stakeholder perceptions of value versus impact. The relationship between tangible and intangible values and impacts of heritage is a two-fold process where value can affect impacts which in turn can lead to changes in value (CHCfE, 2015).

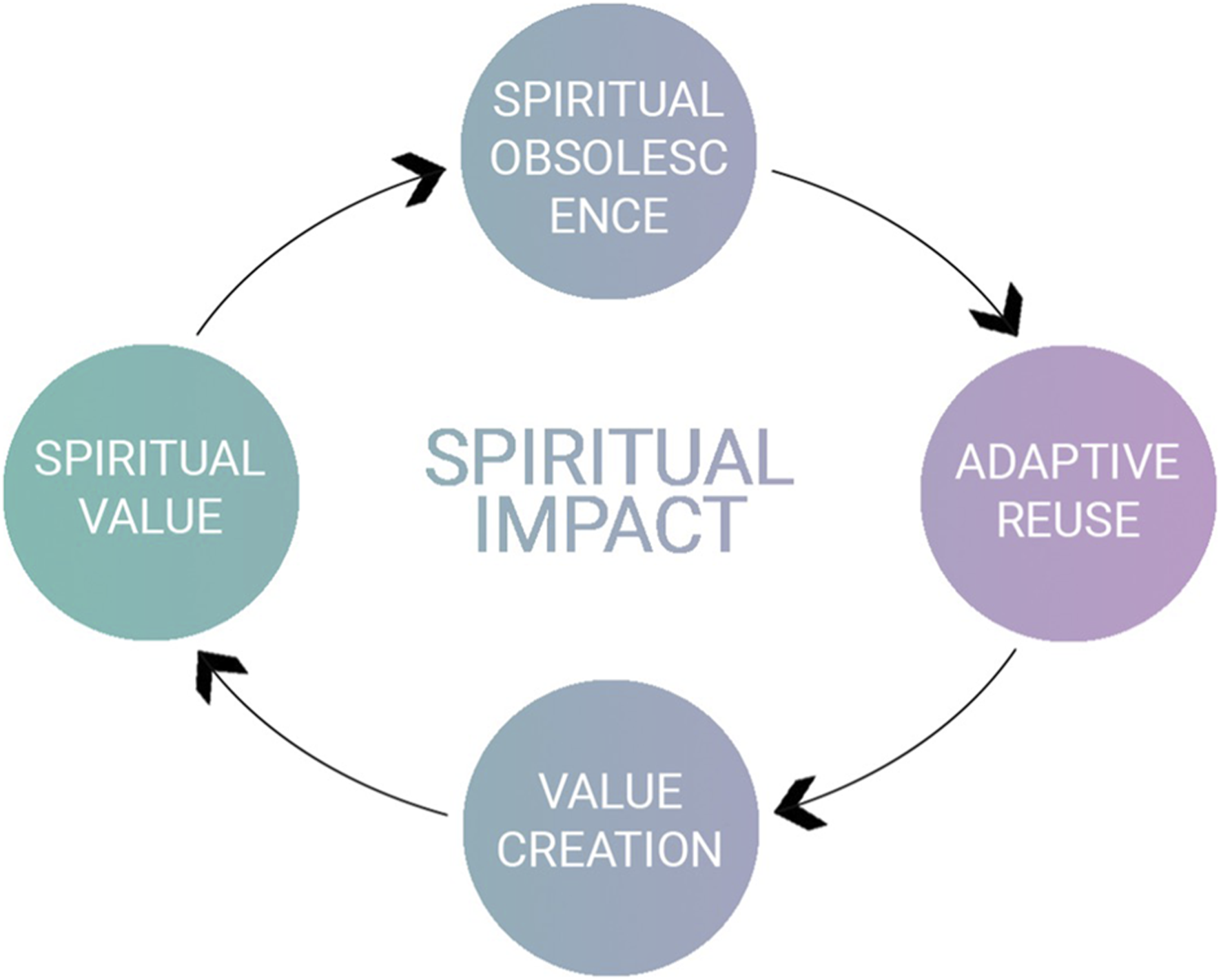

Utilizing this approach, integrated values and impacts are connected via the process of adaptive reuse within a religious structure’s life cycle (see Figure 2). Adaptive reuse of underutilised or abandoned ecclesiastic heritage may alter value perceptions by stakeholders, which in turn may generate impacts (positive and negative impacts), which may further influence value perceptions. Value creation, which results in added values such as community amenity improvement, public goods and social interaction, can bring about both tangible and intangible positive externalities to the neighbourhood (Kee, 2019).

FIGURE 2

Spiritual value and impact. Source: Own.

Forms of ecclesiastical obsolescence and dimensions of adaptability

Obsolescence can be defined as “the state of becoming old-fashioned and no longer useful” (Hornby, 2010, p. 1050). Obsolete buildings negatively impact on the “sense of place” of urban/rural settlements, creating a downward pressure on social, cultural, environmental and economic values. Numerous literature sources deal with categorisation of the forms of obsolescence relating to cultural heritage, including Physical, Functional, Economic, Social, Legal, Aesthetic, Environmental, and Site (Williams, 1986; Barras and Clark, 1996; Wilkinson, 2011; Wilkinson et al., 2014).

Even though religious beliefs remain strong in contemporary society, religious behaviour is changing and this is happening on contradictory paths with church attendance declining and people increasingly describing their beliefs as “spiritual,” rather than “religious” (Inglehart and Baker, 2000). Pinelli and Einstein (2019) argue that these apparently contradictory trends can be reconciled through an examination of religion’s ability to satisfy the need for socialization and social belonging. Further, they suggest that in modern society, religion has a diminishing capacity to provide social identity and opportunities of intense socialization. As such, religious heritage assets of many countries have lost their function. This process indicates the presence of a ‘Spiritual’ form of obsolescence for ecclesiastical heritage.

Value Judgements, Forms, Aspects, and Factors of Obsolescence particular to ecclesiastic architecture are presented in Table 1.

TABLE 1

| Form of obsolescence | Aspects | Factors | Erosion of Value(s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Physical (structural) | Structural stability | Structure failure | Architectural and Symbolic Value |

| Weather tightness | Deterioration | ||

| Overall performance | Dilapidation | ||

| Envelope quality | Urban blight | ||

| Functional (locational) | Fulfillment of purpose | Decreased utility | Spiritual Values |

| Degree of use | Inadequacy | ||

| Technological adequacy | Incapacity | ||

| Contextual fit | Errors and omissions in the building’s layout and form | ||

| Technical advances | |||

| Economic (financial) | Cost effectiveness | Rental income levels | Economic Value |

| Rate of return | Capital value versus adaptation value | ||

| Depreciation | Oversupply or drop in demand | ||

| Economic rationale | Imbalance between costs and benefits | ||

| Demand of services | |||

| Social (cultural) | Satisfaction of human needs | Demographic trends and shifts | Social and Emotional Values |

| Cultural requirements | Changes in trends and society needs | ||

| Local expectations | Changes in expectancy levels | ||

| Legal (tenure) | Compliance with statutory regulations | Changes in legislation or regulations | Political Values |

| Changes in planning policies | |||

| Existing adverse legislation | |||

| Nuisances and hazards—dangerous buildings | |||

| Disagreements between landlord and occupier | |||

| Aesthetic (visual) | Style of architecture is no longer modern | Buildings with additional parts dedicated to different times | Historical and Aesthetic Values |

| Outdated appearance | Lost original parts of the appearance | ||

| Environmental | Environmental stability | Environmental changes | Environmental Value |

| Site | Site value | Disbalance between site and building value | Economic Value (Residual site Value) |

| Building value | |||

| Spiritual | Religious/social identity | Diminished capacity to provide a religious/social identity and opportunities of intense socialization | Spiritual Values |

| Socialization |

Value judgements, forms, aspects, and factors of obsolescence particular to ecclesiastic architecture. Source: Adapted from Wilkinson (2011).

To draw some broad observations: a decline in architectural and symbolic values can result in the development of physical obsolescence. Low or declining spiritual (religious) values lead to the development of functional forms of obsolescence. Altered perceptions by communities of the social value of ecclesiastic heritage impact social obsolescence, while disembodiment of political value can potentially provoke every form of obsolescence. As the economic (market) value of abandoned religious structures (bricks and mortar) declines over time due to obsolescence, the residual site value (alternative development market value of the land beneath the building) will increase until the marketplace may dictate demolition of the historic structure, unless it is protected by heritage legislation.

Dimensions of Adaptability indicate what types of changes can potentially be applied to a building to overcome its obsolescence. This research paper utilizes six general cultural heritage dimensions of adaptability—Adjustable, Versatile, Refitable, Convertible, Scalable and Movable, identified by Heidrich et al. (2017), which have been adapted in religious context.

In religious context,

• Adjustable dimension of adaptability indicates a “change of tasks” by users on a daily/monthly basis. “Change of tasks” means having a multi-purpose space inside a former church, ready to be used for multiple tasks with no/few adjustments. For instance, dividing space with movable walls to ensure the change of tasks.

• Versatile dimension of adaptability indicates a “change of space” and location of services by users on a daily/monthly basis. This may be possible through using movable furniture and equipment.

• Refitable dimension of adaptability indicates a “change of performance” that can be achieved by improving the performance of one or more components, without the need for replacing the entire system (Heidrich et al., 2017).

• Convertible dimension of adaptability indicates a “change of function,” which may be achieved through adaptive reuse of a church.

• Scalable dimension of adaptability indicates a “change of capacity,” such as being able to increase/decrease surfaces and volumes of a church without major effort.

• Movable dimension of adaptability indicates “change of the location in the urban fabric,” which means being able to move the entire building, which is usually possible only when adapting wooden log churches.

Relationship patterns between stakeholder perceptions of value and obsolescence

Stakeholder perceptions of obsolescence and related loss in value in relation to abandoned ecclesiastical built heritage has the potential to combine into a vicious downward spiral which takes momentum as the years pass by. Each form of obsolescence is the result of a decrease of a particular value, which further influences the presence of obsolescence and leads to further erosion of ecclesiastic value. The relationship between “nomadic” perceptions of value and the resultant impact on various forms of obsolescence have a complex and essentially reciprocal nature, although connections between given values of ecclesiastic cultural heritage and forms of obsolescence are not static as human perceptions change over time. While it is evident that observations on the relationship between value and obsolescence cannot be ranked in order nor are the relationships mutually exclusive, the following observations provide a general idea of the complex relationship between value judgements and forms of obsolescence. Essentially, erosion of a combination of cultural, social, environmental, and economic values in different proportions impacts on spiritual forms of obsolescence, depending on the variables of each case.

Methods

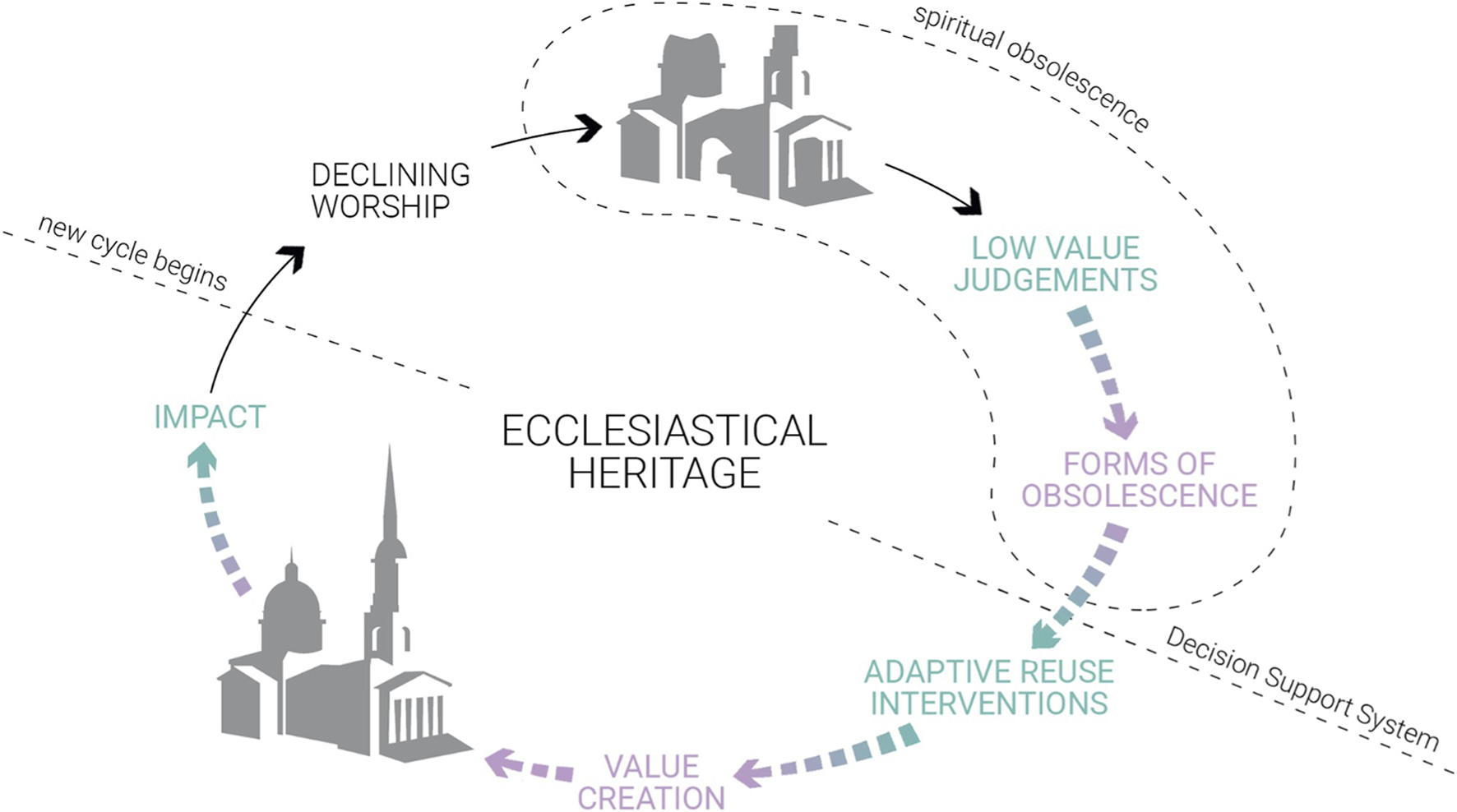

Sixty-five international adaptive reuse case studies have been collated and analysed to establish connections between ecclesiastical values, forms of obsolescence, new uses, value creation, impact and sustainable development. Based on the study of the types of Values and Forms of Obsolescence attributed to religious heritage, the authors study 1) the presence of different pre-adaptation Forms of Obsolescence of the case studies; 2) What Use Interventions can potentially be applied to heritage with such obsolescence; 3) What added value can be created after the adaptation applying reuse Interventions; 4) What impact can be generated once the religious heritage is adapted. These aspects and their connections with each other, which will be observed among the case studies of this paper, are highlighted in Figure 3. Dimensions of Adaptability indicate what types of changes can potentially be applied to a building to overcome its obsolescence. This research paper utilizes six general cultural heritage dimensions of adaptability, which were explained in more detail in the previous section, — Adjustable, Versatile, Refitable, Convertible, Scalable and Movable, identified by Heidrich et al. (2017), which have been adapted in religious context.

FIGURE 3

Focus of the study. Source: Own.

The forms of obsolescence, new uses and use interventions among case studies

In previous eras, cultural and political factors were the predominate forces at work behind some of the more notable adaptations of religious heritage projects (Ahn 2007). Today, there are a wide range of solutions that have been generated for adaptation of churches (Kiley 2004) exhibiting various Forms of Obsolescence; and it is notable that a building may be characterized by several Forms at the same time. This research studies what kinds of adaptation solutions were generated based on different Forms of Obsolescence and Dimensions of Adaptability in 65 selected Case Studies from Europe, the United States, Australia, and Asia (see Table 2). The case studies were selected based on open data published on the Internet. The Author selected the cases which, in her opinion, are pieces of high-quality architecture. The Forms of Obsolescence (pre-adaptation) were established based on the observations by the authors, while the decision on the Dimension of Adaptability particular to each Case Study was based on the type of new use.

TABLE 2

| № | Project title | New use | Pre-adaptation form of obsolescence | Dimension of adaptability | Type of use interventions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Community Centre “De Petrus” (Vught, Netherlands) | Multifunctional centre: library, museum, bar, shops | Social | Convertible | Art and Cultural Activities |

| Spiritual | |||||

| 2 | Church of Santa Barbara—“Church Brigade” (Llanera, Spain) | Skate park | Social | Convertible | Community and Institutional Uses |

| Spiritual | |||||

| 3 | Church of a Former Military Hospital—Jane Restaurant (Antwerp, Netherlands) | Restaurant | Social | Convertible | Commercial Post-Religious Use |

| Spiritual | |||||

| 4 | St. Paul and St. George Church (Edinburgh, United Kingdom) | Place of worship with opportunities for flexible use | Economic | Refitable | Extended Religious Use |

| Functional | |||||

| 5 | Woonkapel—Chapel Residence (Utrecht, Netherlands) | Single-family house | Social | Convertible | Residential Post-Religious Use |

| Spiritual | |||||

| 6 | The Chapel on the Hill (Forest-In-Teesdale, United Kingdom) | Single-family house | Social | Convertible | Residential Post-Religious Use |

| Aesthetic | |||||

| Physical | |||||

| Spiritual | |||||

| 7 | Convent of Sant Francesc (Santpedor, Spain) | Auditorium, multipurpose cultural space | Physical | Convertible | Art and Cultural Activities |

| Spiritual | |||||

| 8 | Nottingham Church Bar (Nottingham, United Kingdom) | Bar-restaurant | Social | Convertible | Commercial Post-Religious Use |

| Spiritual | |||||

| 9 | Selexyz Dominicanen (Maastricht, Netherlands) | Bookstore | Social | Convertible | Commercial Post-Religious Use |

| Spiritual | |||||

| 10 | Martin’s Patershof Hotel (Mechelen, Belgium) | Hotel | Social | Convertible | Commercial Post-Religious Use |

| Spiritual | |||||

| 11 | St. Sebastian Kindergarten (Munster, Germany) | Kindergarten | Social | Convertible | Community and Institutional Uses |

| Economic | |||||

| Spiritual | |||||

| 12 | National Marine Museum of Ireland (Dun Laoghaire, Ireland) | Marine museum | Social | Convertible | Art and Cultural Activities |

| Economic | |||||

| Functional | |||||

| Spiritual | |||||

| 13 | Reption Park Swimming Pool (Woodford, United Kingdom) | Swimming pool | Social | Convertible | Community and Institutional Uses |

| Economic | |||||

| Spiritual | |||||

| 14 | Gattopardo Milano (Milan, Italy) | Bar, disco | Social | Convertible | Commercial Post-Religious Use |

| Economic | |||||

| Spiritual | |||||

| 15 | Old Church of San Lorenzo (Venice, Italy) | Multipurpose cultural space | Social | Refitable | Art and Cultural Activities |

| Physical | |||||

| Spiritual | |||||

| 16 | Supercomputing Centre (Barcelona, Spain) | Office | Social | Convertible | Office Post-Religious Use |

| Economic | |||||

| Spiritual | |||||

| 17 | San Barnaba (Venice, Italy) | Exhibition centre | Social | Convertible | Art and Cultural Activities |

| Spiritual | |||||

| 18 | Fabrica (Brighton, United Kingdom) | Centre for contemporary art | Social | Convertible | Art and Cultural Activities |

| Functional | |||||

| Spiritual | |||||

| 19 | Church of San Sisto al Carrobbio (Milan, Italy) | Museum-studio of Francesco Messina | Social | Convertible | Art and Cultural Activities |

| Spiritual | |||||

| 20 | Church of Santa Teresa and Giuseppe (Milan, Italy) | Media library | Social | Convertible | Community and Institutional Uses |

| Spiritual | |||||

| 21 | Church of San Paolo Converso (Milan, Italy) | Office | Social | Convertible | Office Post-Religious Use |

| Spiritual | |||||

| 22 | Private House in a Church (Italy) | Single-family house | Social | Convertible | Residential Post-Religious Use |

| Functional | |||||

| Spiritual | |||||

| 23 | Church of San Carpoforo (Milan, Italy) | Multi-art centre of Brera Academy of fine arts | Social | Refitable | Community and Institutional Uses |

| Spiritual | |||||

| 24 | Church of Saint Simone and Guida (Milan, Italy) | Theatre school | Social | Convertible | Community and Institutional Uses |

| Spiritual | |||||

| 25 | St. Maximin’s Abbey (Trier, Germany) | Concert hall, school gym | Aesthetic | Convertible | Community and Institutional Uses |

| Functional | |||||

| Spiritual | |||||

| 26 | Bethlehem-Kirche (Hamburg, Germany) | Kindergarten | Social | Convertible | Community and Institutional Uses |

| Economic | |||||

| Spiritual | |||||

| 27 | Cantonese Eatery Duddell’s (London, United Kingdom) | Restaurant | Social | Convertible | Commercial Post-Religious Use |

| Spiritual | |||||

| 28 | Red Brick Building (Brussels, Belgium) | Office | Social | Convertible | Office Post-Religious Use |

| Functional | |||||

| Spiritual | |||||

| 29 | Kaiser Wilhelm Memorial Church (Berlin, Germany) | Church, museum, memorial complex | Physical | Refitable | Extended Religious Use |

| 30 | Carmo Convent (Lisbon, Portugal) | Museum | Physical | Convertible | Art and Cultural Activities |

| Spiritual | |||||

| 31 | Rievaulx Abbey (Helmsley, United Kingdom) | Museum | Physical | Convertible | Art and Cultural Activities |

| Spiritual | |||||

| 32 | Santa Maria de Vilanova de la Banca (Vilanova de la Banca, Spain) | Museum, multi-purpose space | Physical | Refitable | Art and Cultural Activities |

| Spiritual | |||||

| 33 | St. Martin-in-the-Fields (London, United Kingdom) | Parish church and concert venue | Economic | Adjustable | Extended Religious Use |

| Functional | |||||

| 34 | Stadtkirche Müncheberg (Muncheberg, Germany) | Parish church, library and venue place | Economic | Adjustable | Extended Religious Use |

| Functional | |||||

| 35 | Paul Street—EC2 (Shoreditch, United Kingdom) | Apartments, residential | Physical | Scalable | Residential Post-Religious Use |

| Spiritual | |||||

| 36 | The South River Vineyard (Shalersville was moved to Harpersfield, United States) | Winery | Social | Movable | Commercial Post-Religious Use |

| Physical | |||||

| Spiritual | |||||

| 37 | Children’s Day School (San-Francisco, United States) | School | Social | Convertible | Community and Institutional Uses |

| Economic | |||||

| Spiritual | |||||

| 38 | Catalysis (Seattle, United States) | Office of marketing agency | Social | Convertible | Office Post-Religious Use |

| Functional | |||||

| Spiritual | |||||

| 39 | Fremont Abbey (Seattle, United States) | Arts centre | Social | Convertible | Art and Cultural Activities |

| Functional | |||||

| Spiritual | |||||

| 40 | Transformazium (Braddock, United States) | Community centre | Social | Convertible | Community and Institutional Uses |

| Functional | |||||

| Physical | |||||

| Spiritual | |||||

| 41 | The Castle (Beloit, United States) | Multi-purpose venue space | Social | Refitable | Art and Cultural Activities |

| Economic | |||||

| Spiritual | |||||

| 42 | Sacred Heart (Augusta, United States) | Venue space, office | Social | Convertible | Office Post-Religious Use |

| Economic | |||||

| Spiritual | |||||

| 43 | McColl Centre (North Carolina, United States) | Visual arts museum | Social | Convertible | Art and Cultural Activities |

| Functional | |||||

| Spiritual | |||||

| 44 | Former Church in Surry Hills (Surry Hills, Australia) | Office | Economic | Convertible | Office Post-Religious Use |

| Spiritual | |||||

| 45 | Hospital Hotel (Tel Aviv, Israel) | Hotel | Functional | Convertible | Commercial Post-Religious Use |

| Spiritual | |||||

| 46 | Thomas Burgh House (Dublin, Ireland) | Office | Social | Convertible | Office Post-Religious Use |

| Aesthetic | |||||

| Spiritual | |||||

| 47 | Rush Library (Rush, Ireland) | Library | Social | Convertible | Community and Institutional Uses |

| Spiritual | |||||

| 48 | All Saints Church (Hereford, United Kingdom) | Parish church, community centre and a cafe | Economic | Adjustable | Extended Religious Use |

| Functional | |||||

| 49 | The ‘Waterdog’ (Limburg, Belgium) | Workplace | Social | Convertible | Office Post-Religious Use |

| Aesthetic | |||||

| Spiritual | |||||

| 50 | The Cathedral of Liverpool (Liverpool, United Kingdom) | Parish church and exhibition space | Functional | Versatile | Extended Religious Use |

| 51 | Pearse Lyons Distillery (Dublin, Ireland) | Distillery | Social | Convertible | Commercial Post-Religious Use |

| Economic | |||||

| Aesthetic | |||||

| Spiritual | |||||

| 52 | Smock Alley Theatre (Dublin, Ireland) | Theatre | Social | Convertible | Art and Cultural Activities |

| Spiritual | |||||

| 53 | The Holy Cross Church and Parish Centre (Dundrum, Ireland) | Parish church and parish centre | Functional | Adjustable | Extended Religious Use |

| 54 | The Church (Former St. Mary’s Church) (Dublin, Ireland) | Restaurant | Social | Convertible | Commercial Post-Religious Use |

| Functional | |||||

| Spiritual | |||||

| 55 | Medieval Mile Museum (Kilkenny, Ireland) | Museum | Social | Convertible | Art and Cultural Activities |

| Functional | |||||

| Spiritual | |||||

| 56 | St. Laurence’s Chapel, Grangegorman (Dublin, Ireland) | Multi-purpose venue space | Social | Refitable | Community and Institutional Uses |

| Functional | |||||

| Economic | |||||

| Spiritual | |||||

| 57 | St. Andrew’s Church (Dublin, Ireland) | Design and exhibition centre with café and offices | Social | Convertible | Commercial Post-Religious Use |

| Spiritual | |||||

| 58 | St. George’s Church (Dublin, Ireland) | Office | Social | Convertible | Office Post-Religious Use |

| Economic | |||||

| Spiritual | |||||

| 59 | Scots Presbyterian Church (Dublin, Ireland) | Office | Social | Convertible | Office Post-Religious Use |

| Spiritual | |||||

| 60 | St. Kevin’s Church (Dublin, Ireland) | Apartments, residential | Social | Convertible | Residential Post-Religious Use |

| Spiritual | |||||

| 61 | Cahernorry Church (Ballyneety, Ireland) | Single-family house | Social | Convertible | Residential Post-Religious Use |

| Spiritual | |||||

| 62 | Franciscan Church (Drogheda, Ireland) | Exhibition space | Social | Convertible | Art and Cultural Activities |

| Spiritual | |||||

| 63 | St. Aidan’s Church (Brookline, United States) | Apartments, residential | Social | Convertible | Residential Post-Religious Use |

| Spiritual | |||||

| 64 | The Church of St. Peter Chesil (Winchester, United Kingdom) | Theatre | Social | Convertible | Art and Cultural Activities |

| Physical | |||||

| Spiritual | |||||

| 65 | St. Nicholas Collegiate Church (Galway, Ireland) | Shared place of worship | Functional | Adjustable | Extended Religious Use |

Graphical presentation of case studies: New uses along with forms of obsolescence and dimensions of adaptability.

New uses applied to the case studies are categorised into different types of Use Interventions, as they indicate different types of changes applied to a religious building and are divided into Extended Religious Use and/or Functional Conversion. Extended Religious Use means shared use, in time or in space, of a church for religious and non-religious purposes. Functional conversion means adaptive reuse to a single or mixed non-religious use that is further categorised as Arts and Cultural Activities, Community and Institutional Uses, Commercial Post-Religious Use (retail, hotel, restaurants), Residential Post-Religious Use, and Office Post-Religious Use.

Results

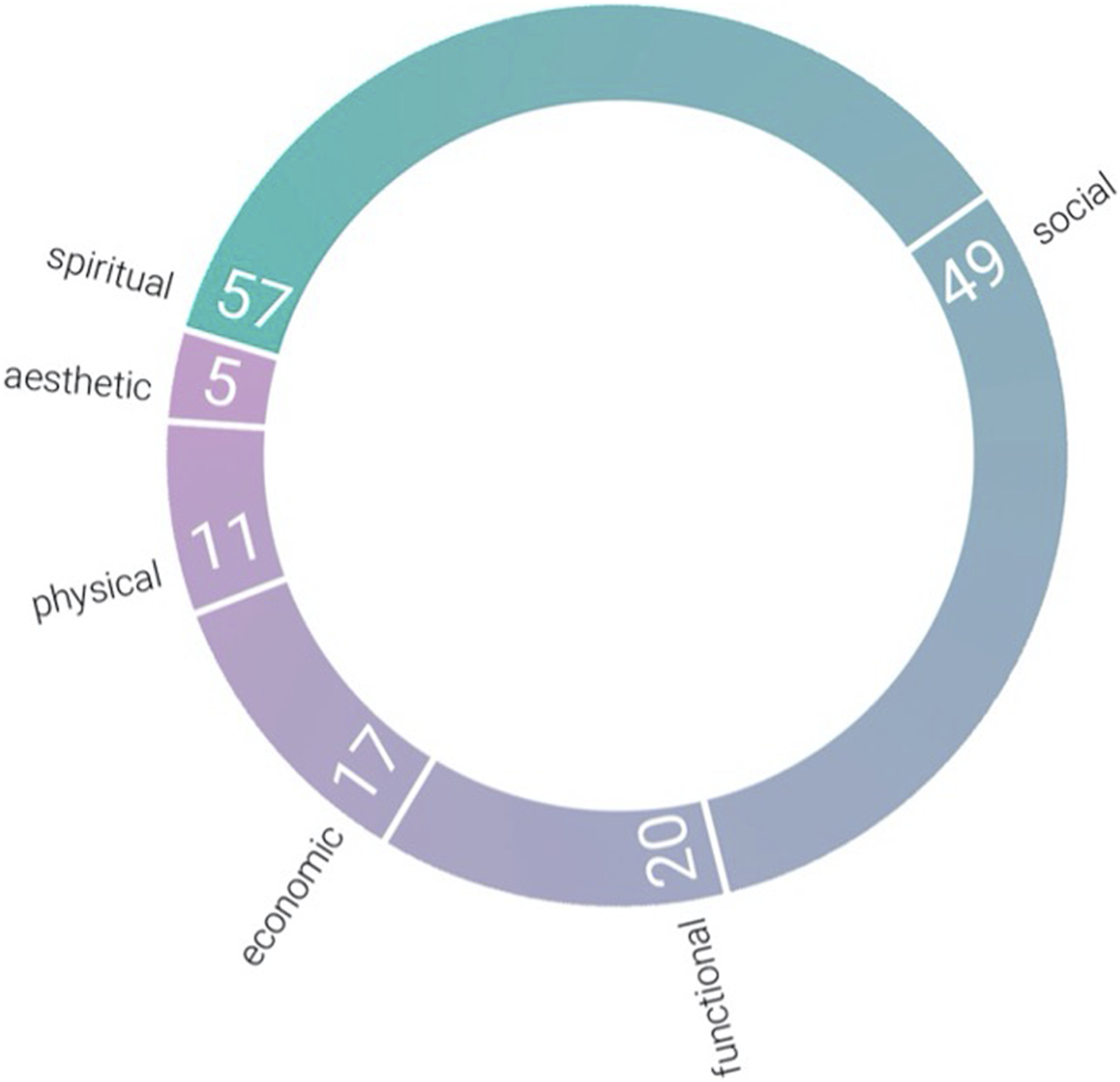

The ratios for Forms of Obsolescence represented in Figure 4 illustrate that the majority of Case Studies (88%) primarily exhibit Spiritual Form of Obsolescence (57 out of 65 cases), while zero cases indicate any Legal Obsolescence. All case studies exhibiting Spiritual Form of Obsolescence underwent a change of “function” indicating “Convertible” Dimension of Adaptability. Thus, the Authors observe that adaptive reuse of religious architecture involving a change of function (Convertible) to a new non-religious use followed a period of Spiritual Obsolescence where the ecclesiastical resources concerned irrevocably lost their ability to remain a place for worship and socialization.

FIGURE 4

Case studies: Forms of obsolescence (amount). Source: Own.

The ratios for Dimensions of Adaptability for each Case Study are represented in Figure 5, resulting in 50 out of 65 cases exhibiting primarily convertibility (Convertible Dimension of Adaptability), meaning that the feasibility of the original function change is centred around the change of spaces and services.

FIGURE 5

Case studies: Dimensions of adaptability (amount). Source: Own.

Generally, the assessment of Impact on ecclesiastical cultural heritage rests on four interrelated pillars of sustainable development (Economic, Social, Cultural and Environmental), serving as a sustainable base for the assessment of cultural heritage impact (CHCfE, 2015).

Case study observations on the reciprocal relationship between Use Interventions, Forms of Obsolescence and Dimensions of Adaptability are as follows:

• Based on the observation of case studies, Extended Religious Use is a means of adaptive reuse for ecclesiastic heritage with Economic or Functional Forms of Obsolescence. The religious heritage assets suitable for this type of Use Intervention should have Refitable or Adjustable Dimension of Adaptability.

• The use for Arts and Cultural Activities was successfully applied for cultural heritage with Spiritual, Social, Physical, Economic, or Functional Forms of Obsolescence; and Convertible or Refitable Dimension of Adaptability.

• Community and Institutional Uses were applied to ecclesiastic heritage with Spiritual, Social, Economic, Aesthetic, Functional, and Physical Forms of Obsolescence; and Convertible or Refitable Dimension of Adaptability.

• Commercial Post-Religious Use was applied to buildings with Spiritual, Social, Economic, Physical, Aesthetic, and Functional Forms of Obsolescence; and Convertible or Movable Dimension of Adaptability.

• Residential Post-Religious Use was applied to religious buildings with Spiritual, Social, Aesthetic, Physical, and Functional Forms of Obsolescence; and Convertible or Scalable Dimension of Adaptability.

• Office Post-Religious Use was applied to buildings with Spiritual, Social, Economic, Functional, and Aesthetic Forms of Obsolescence; and only Convertible Dimension of Adaptability.

Case study observations on the reciprocal relationship between Use Interventions and Value Creation are as follows:

• Considering the fact that particular Forms of Obsolescence follow the decrease of correspondent Value judgements by society, each type of Use Interventions is intended to support Value Creation for ecclesiastical cultural heritage.

• The adaptation of ecclesiastic heritage to Extended Religious Use can overcome the lack of Economic, Cultural and Spiritual values. As such, Extended Religious Use generates Economic and Cultural (spiritual) value.

• The adaptation to Arts and Cultural Activities can overcome the lack of given Social, Cultural (architectural, symbolic, spiritual) and Economic values. As such, Arts and Cultural Activities generate Social, Architectural, Symbolic, Economic, and Spiritual values.

• Adaptation reuse to Community and Institutional Uses and Commercial Post-Religious Use can overcome the lack of Social, Economic, Cultural (architectural, symbolic, historical, aesthetic, and spiritual) values. As such, Community and Institutional Uses and Commercial Post-Religious Use generate Social, Economic, and Cultural (architectural, symbolic, historical, aesthetic and spiritual) value.

• The adaptation to Residential Post-Religious Use can overcome the lack of Social and Cultural (historical, aesthetic, architectural, symbolic and spiritual) values. As such, Residential Post-Religious Use generates Social and Cultural (historical, aesthetic, architectural, symbolic and spiritual) values.

• The adaptation to Office Post-Religious Use can overcome the lack of Social, Economic, and Cultural (spiritual, historical, aesthetic) values of obsolete and abandoned religious assets. As such, Office Post-Religious Use generates Social, Economic, and Cultural (spiritual, historical, aesthetic) values.

Table 3 highlights the potential areas of impact following the adaptive reuse of ecclesiastic heritage.

TABLE 3

| The domains | The sub-domains | A | B | C | D | Positive impact | Negative impact | Affected stakeholders |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Built Heritage and Real Estate Market | Real Estate Market | o | o | - High demand to live in a neighborhood of the historical church | - Heritage status of a church can bring restrictions and difficulties in the neighborhood | The Church, the Investor, the Developer, the Community, the Public | ||

| Regional Competitiveness | o | o | o | - restrictions for owners regarding the use and adaptation | ||||

| Regional Attractiveness | o | o | o | - an increase of property prices | - increase of property prices CHCfE (2015) | |||

| Labour Market | - | o | o | - direct and indirect creation of jobs | - part-time jobs | The Investor, the Developer, the Community, the Public | ||

| - a need to train and educate workers | ||||||||

| Economic Capital | Gross Value Added (GVA) | o | - generator of tax revenue for public authorities, both from the economic activities of heritage-related sectors and indirect or induced activities | - weak sustainable development when solely economic capital is considered CHCfE (2015) | The Church, the Investor, the Developer | |||

| Return of Investment | o | - spillovers from heritage-oriented projects leading to further investment | ||||||

| Tax Income | o | - track record on good return on investment CHCfE (2015) | ||||||

| Tax Reductions | o | |||||||

| Social Programs Funding | o | o | ||||||

| Sense of a Place | Place Branding | o | o | - preservation of traditions | - replacing history with a beautiful “image” of cultural heritage | The Community | ||

| Image and Symbols Creation | o | - attractive impact on people’s sense of identity | - visitors congestion | |||||

| Creativity and Innovation | o | - attractive image of a building | - loss of personal affiliation to cultural heritage | |||||

| Visual Comfort | o | o | o | - attractive image of cities, districts | ||||

| Place-Making | o | o | ||||||

| Magnet Effect | o | |||||||

| Religious Identity | Religious Architecture Language | o | o | - creation of intangible value | - social exclusion | The Church, the Community | ||

| Sense of Religious Place | o | o | o | - symbolic value | - the study of vernacular knowledge may need time and human resources | |||

| Vernacular Knowledge | o | o | - spiritual value | |||||

| Knowledge of Tradition | o | o | o | - preservation of traditions | ||||

| National Identity | o | o | - creation of “vernacular” jobs | |||||

| “Collective Memory” | o | o | ||||||

| Respect of The House Of God | o | o | ||||||

| Community Identity | o | |||||||

| Environmental Sustainability | Historic Cultural Landscape | o | o | - sustainable management of cultural heritage stock | - high consumption of resources | The Public | ||

| Reducing Urban Sprawl | o | o | - reducing demolition and rebuilding | - low ecological index of buildings | ||||

| Life Cycle Prolongation | o | - prolongation of the physical life of buildings | ||||||

| Structural Resistance | o | - influence on demographic change | ||||||

| Community Participation | Education Engagement | o | o | o | - social inclusion | - disintegration of “native” users | The Church, the Community | |

| Sport Engagement | o | o | - sense of civic pride | - social exclusion | ||||

| Art Engagement | o | o | o | - creation of inclusive environments | ||||

| Social Wellbeing | o | - community engagement | ||||||

| Tourism | o | o | o | - gaining knowledge and skills | ||||

| Experience | o | o | - personal development | |||||

| - basis for community cooperation | ||||||||

| Community Interest | Social Cohesion | o | - basis for community cooperation | - “Not in My Backyard” attitudes CHCfE (2015) | The Church, the Investor, the Developer, the Community, the Public | |||

| Community Involvement | o | - satisfaction of social wants | ||||||

| Continuity of Social Life | o | - local enterprises | ||||||

| Public Interest | o | o | - interests of all stakeholders | |||||

| Private Interest | o |

The potential areas of the impact of the adaptation of ecclesiastic heritagea. Source: own. The methodology was adapted from CHCfE (2015).

Names of the columns: A—Economic aspect; B—Social aspect; C—Cultural aspect; D—Environmental aspect.

The combination of Impacts (economic, social, cultural, and environmental) forming a holistic landscape perspective and the categorization of Domains were provided by CHCfE (2015) and adapted for ecclesiastical Impact evaluation. The framework of Impact Domains of cultural heritage, and religious cultural heritage in particular, presented in Table 3 serves as a sustainable base for the assessment of cultural heritage impact. The Domains presented in Table 3 are the Domains of potential impact of adaptation. The four pillars of assessing the Impact of the adaptation of religious buildings are economic, cultural, social, and environmental. Each pillar is the amalgamation of various Domains, with some of them attributable to two or three pillars at once, depending on the Domain (see Figure 6). The creation of sub-domains and the division into identified positive and negative ecclesiastical impacts were based on case study observations by the Author. Among the most valuable sub-domains (which contribute to three pillars of sustainable development at once) are the following: regional competitiveness, regional attractiveness, visual comfort, place-making, sense of religious space, knowledge of tradition, education engagement, art engagement, and tourism.

FIGURE 6

Four impacts of the adaptation of religious built cultural heritage as four pillars of sustainable development. Source: own. The methodology was adapted from CHCfE (2015).

Ideally, impacts should reflect total expenditure (public and private) per capita spent on the preservation, protection and conservation of said cultural heritage, level of government (national, regional and local/municipal), type of expenditure (operating expenditure/investment) and type of private funding (donations in kind, private non-profit sector and sponsorship), as it indicates the achievement of Sustainable Development Goal 11 of SDGs (United Nations, 2015).

Each impact is presented according to affected stakeholders, as it helps to understand how the adaptive reuse of ecclesiastic heritage impacts on society. The Church stakeholders include two of the main functional groups: the Archdiocesan organisation and parish, or ex-parish, which includes ex-believers who used to attend church services in the former church. The Investor consists of insurance companies, independent investors, professionals who have capital to invest, commercial banks, private equity firms, and real estate investment trusts (REITs). The Developer represents organisations that bring together investors, producers and marketeers during the adaptive reuse process. The Public incorporates policymakers and regulators, including government administrations, local authorities, fire and building surveyors. The Community, in the adaptive reuse of religious heritage, includes future users and local community who live in the district, non-profit organisations, and parishioners (or ex-parishioners).

The conducted analysis shows that every Domain incorporates several layers of inter-related impacts, and sometimes overlapping economic, social, cultural and environmental impacts. Some brief observations can be made in relation to the sixty-five international case studies:

• “Built Heritage and Real Estate Market” Domain generates lower social, and higher economic and environmental impacts with potential for social, economic and environmental value creation;

• “Labour Market” generates equally economic and social impacts with potential for economic and social value creation;

• “Economic Capital” generates higher economic and lower social impact with potential for economic and social value creation;

• “Sense of a Place” generates higher social and cultural impacts, and lower economic and environmental impacts with potential for social, cultural, economic and environmental value creation;

• “Religious Identity” generates higher social and cultural impacts, and lower economic and environmental impacts with potential for social, cultural, economic and environmental value creation;

• “Environmental Sustainability” generates higher environmental impacts, and lower economic and cultural impacts with potential environmental, economic and cultural value creation;

• “Community Participation” generates higher social impact, and lower economic and cultural impacts with potential for social, economic and cultural value creation;

• “Community Interest” generates higher social impact and lower economic impact with potential for social and economic value creation.

Discussion

Sixty-five (65) international case studies were examined to explore creative holistic solutions to re-integrating underutilised and disused religious assets back into contemporary urban and rural landscapes. Based on the case studies analysis, this paper explained different values, which can be generated by adaptive reuse of religious built cultural heritage. Value formation in spiritual context based on recognition of the social, cultural, and environmental values and also relying on the social, cultural, and environmental impacts leads to the sustainable development of obsolete churches. The weighting of the likely social, cultural, and environmental impacts of adaptive reuse directly influences the decisions to undertake adaptive reuse projects, based on the assessment of the social, cultural and environmental value judgements of religious objects. It is important to state that in the majority of Cases the economic impact based on the assessment of economic values can be very low, since religious structures are unique architectural objects and historically are not associated with economic (market) values. Throsby (2012) points out the necessity of remembering, when talking about former churches as market objects, that the cultural attributes of religious heritage must also be studied independently from the economic attributes it might possess. Having said that, the case studies indicate that in some instances, sensitive adaptive reuse to Post Religious Uses (Arts and Culture, Residential, Office) may open the door to positive inflows of investment capital with corresponding market impacts based on the economic values attached to new and extended uses.

The conducted analysis provides an insight into how adaptive reuse of abandoned ecclesiastical cultural heritage can be viewed within a circular economy (CE) holistic perspective, by highlighting the multidimensional relationships at play to better understand the potential contribution of a CE framework to achieve human-centred historic landscapes.

This analysis and dialogue on possible new forms of use for religious heritage is mindful of the necessity to respect and protect diverse cultural beliefs and the collective memories of past, present and future communities - worshipers and non-worshipers alike. In this regard, it is important to acknowledge that creative adaptive reuse solutions for ecclesiastical heritage assets are not always directly transferable between regions and cultures due to differing traditional spiritual beliefs and value systems. Supporting cultural diversity by reintegrating abandoned religious resources of all faiths (diverse ideas, beliefs, traditions and collective memory of the religious site) back into the contemporary urban fabric of communities has the potential to yield benefits that contribute to cultural capital.

Statements

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

The author confirms being the sole contributor of this work and has approved it for publication.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

1

Ahn Y. K. (2007). Adaptive reuse of abandoned historic churches: Building type and public perception. PhD thesis (College Station, TX, USA: Texas A&M University).

2

Architects’ Council of Europe (ACE) (2018). Leeuwarden declaration: Adaptive Re-use of the built heritage: Preserving and enhancing the values of our built heritage for future generations, November 2018. Brussels: Architects’ Council of Europe.

3

Barras R. Clark P. (1996). Obsolescence and performance in the Central London office market. J. Prop. Valuat. Invest.14 (4), 63–78. 10.1108/14635789610153470

4

CHCFE Consortium (2015). Cultural heritage counts for Europe. Oslo, Norway: CHCFE Consortium.

5

Council of Europe (COE) (2000). Declaration on cultural diversity, adopted by the committee of ministers 7 december 2000. London, UK: Council of Europe.

6

Dogan H. A. (2019). Assessment of the perception of cultural heritage as an adaptive re-use and sustainable development strategy: Case study of Kaunas, Lithuania. J. Cult. Herit. Manag. Sustain. Dev.9 (3), 430–443. 10.1108/jchmsd-09-2018-0066

7

Douglas J. (2006). Building Adaptation. 2nd ed. London and New York: Spon Press.

8

European Union (EU) (2020). The human centred city: Recommendations for research and innovative actions. Maastricht, Netherlands: European Union.

9

Foster G. (2020). Circular economy strategies for adaptive reuse of cultural heritage buildings to reduce environmental impacts. Resour. Conservation Recycl.152, 104507. 10.1016/j.resconrec.2019.104507

10

Gallou E. Fouseki K. (2019). Applying social impact assessment (SIA) principles in assessing contribution of cultural heritage to social sustainability in rural landscapes. J. Cult. Herit. Manag. Sustain. Dev.9 (3), 352–375. 10.1108/jchmsd-05-2018-0037

11

Heidrich O. Kamara J. Maltese S. Re Cecconi F. Dejaco M. C. (2017). A critical review of the developments in building adaptability. Int. J. Build. Pathology Adapt.35 (4), 284–303. 10.1108/ijbpa-03-2017-0018

12

Hornby A. S. (2010). Oxford advanced learner’s dictionary of current English. 8th ed.Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

13

M. Hutter I. Rizzo (Editors) (1997). (London: Macmillan). Economic perspectives on cultural heritage.

14

ICOMOS (1994). The nara document on authenticity, Japan. Paris, France: ICOMOS.

15

Inglehart R. Baker W. E. (2000). Modernization, Cultural change, and the persistence of traditional values. Am. Sociol. Rev.65 (1), 19–51. 10.2307/2657288

16

Kee T. (2019). Sustainable adaptive reuse – economic impact of cultural heritage. J. Cult. Herit. Manag. Sustain. Dev.9 (2), 165–183. 10.1108/jchmsd-06-2018-0044

17

Kiley C. J. (2004). Convert! The adaptive reuse of churches. Master thesis (Cambridge, MA, USA: Master of science in real estate development and Master in city planning, Massachusetts Institute of Technology).

18

Landry C. Bianchini F. Maguire M. Worpole K. (1993). The social impact of the arts: A discussion document. Stroud, UK: Comedia.

19

Mason R. (2002). “Assessing values in conservation planning: Methodological issues and choices,” in Assessing the value of cultural heritage, Research Report. Editor De la TorreM. (Los Angeles, CA, USA: The Getty Conservation Institute).

20

Ost C. Van N. (1998). Report on economics of conservation: An appraisal of theories, principles and methods. Paris, France: International Economics Committee, ICOMOS.

21

Pickerill T. Armitage L. (2009). “The management of built heritage, A comparative,” in Review of policies & practice in Western Europe, North America & Australia, Pacific Rim Real Estate Society Conference, Sydney. Peer Reviewed.

22

Pickerill T. (2015). “Funding models for city living, historic places living city spaces,” in Conference by Dept. of Arts Heritage and the Gaeltacht, the RIAI, and the Irish Architecture Foundation with City Architects Division, Mansion House, October 2015.

23

Pignataro G. Rizzo I. (1997). “Heritage regulation: Regimes, cases and effects,” in Economic perspectives on cultural heritage. Editors Hutter,M.RizzoI. (London: Macmillan).

24

Pinelli M. Einstein M. (2019). Religion, science and secularization: A consumer-centric analysis of religion’s functional obsolescence. J. Consumer Mark.36 (5), 582–591. 10.1108/jcm-11-2017-2451

25

Sedova A. (2020). Spaces “out of religious use” and ecclesiastic architecture as marketable real estate assets: A potential solution for Russia’s abandoned religious heritage artifacts. PhD thesis (Milan, Italy: Politecnico di Milano).

26

Throsby D. (2012). “Heritage economics: A conceptual framework,” in The economics of uniqueness, investing in historic city cores and cultural heritage assets for sustainable development, urban development series. Editors Liccoardi,G.AmirtahmasebiR. (Washington, DC, USA: The World Bank).

27

UNESCO (2013). Hangzhou declaration: Placing culture at the heart of sustainable development policies. Paris: UNESCO.

28

UNESCO (2001). Universal declaration on cultural diversity. Paris: UNESCO.

29

United Nations (1996). Second UN conference on human settlements (habitat II). Istanbul 1996. San Francisco, CA, USA: United Nations.

30

United Nations (2015). Transforming our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. A/RES/70/1.

31

Wells J. C. Lixinski L. (2016). Heritage values and legal rules. Identification and treatment of the historic environment via an adaptive regulatory framework (part 1). J. Cult. Herit. Manag. Sustain. Dev.6 (3), 345–364. 10.1108/jchmsd-11-2015-0045

32

Wilkinson S. J. Remoy H. Langston C. (2014). Sustainable building adaptation: Innovations in decision-making. Oxford: Wiley Blackwell.

33

Wilkinson S. J. (2011). The relationship between building adaptation and property attributes. PhD thesis (Geelong, Australia: Deakin University).

34

Williams A. BScHons (1986). Remedying industrial building obsolescence: The options. Prop. Manag.4 (1), 5–14. 10.1108/eb006609

Summary

Keywords

adaptive reuse, ecclesiastical cultural heritage, value creation, impact analysis, sustainable development

Citation

Sedova A (2022) Impact analysis on adaptive reuse of obsolete ecclesiastical cultural heritage. Eur. J. Cult. Manag. Polic. 12:11083. doi: 10.3389/ejcmp.2022.11083

Received

21 April 2022

Accepted

01 December 2022

Published

16 December 2022

Volume

12 - 2022

Updates

Copyright

© 2022 Sedova.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Anastasiia Sedova, sedovaanastasiia@yandex.com

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.