Abstract

This paper tentatively introduces the concept of cultural communication, exploring new theoretical and practical perspectives on culture and cultural policy. Notably, it presents a theoretical model for cultural communication as a dedicated, common, widespread communication “mode,” thematising ambiguity. This concept of cultural communication may provide new footholds for the legitimisation of public cultural policy—positioning the arts firmly within the context of cultural communication—and for the practical, heuristic application in a structured practice of arranging cultural encounters, carried out in Netherlands.

Introduction

In the past decades, the legitimisation of cultural policy in Western Europe has been shaken by, for example, sociological deconstruction, post-colonialism, diversification, neoliberal strands in government and populist rhetoric—in combination with societal changes such as digitalisation, globalisation, segregation and austerity. Urgent calls are sounding for new, more encompassing views on the meaning and value of culture as well as for practical policy goals and outcome evaluation tools (e.g., Holden, 2006; Stevenson, 2016; Wilson, 2017; Hadley and Belfiore, 2018). Clearly, a wider dissatisfaction with—or contention of—the “deficit model” of cultural policy is growing in strength and a new “democratic” case for the meaning and value of culture, inclusiveness, new audiences, multiculturality, cultural capabilities and local ecosystems is emerging (e.g., Ahmed, 2012; Gielen et al., 2014; Holden 2015; UCLG, 2020; EU, 2021).

This may be seen against the backdrop of the emergence of culture as a designated theme for global democracy and sustainability (e.g., Kagan, 2011; UNESCO, 2022), while the rise of social media and networked societies adds further urgency and depth to the discourse on what it entails to live together—and the role “culture as a public good” (UNESCO, 2022) may play in both the local and the global, in (post-)pandemic times.

In this transitional policy-landscape the key concepts (culture, the arts, democracy, policy) have started drifting. Loosely scanning policy documents,1 the term “culture” may, for example, mean: way of life, civilisation, identity-set, value-set, heritage, expressions, the arts or a combination of those. “The arts” may indicate: artifacts, disciplines, artistic practice, expressions, creativity, creative industry. Democracy (in a cultural context)2 may refer to: representation, deliberation, participation, pluriformity, diversity, inclusiveness, or cultural struggle. “Policy” may indicate the dimensions of politics, policy or governance. To complicate things further, arguments tend to switch back and forth between individual, group and societal perspectives, between local, regional, national, international and supra-national perspectives; between intrinsic and instrumental (economic, social, wellbeing, education, creativity, sustainability) perspectives, and between legitimisation, strategy and effectiveness dimensions.3

There are practical reasons for these entanglements to persist: within day-to-day realpolitik, culture is typically a “weak” portfolio, charged with contested images; the pragmatics of “making the case” usually prevail over the muddy waters of conceptual discourse. These pragmatics occur in local politics, but also in national and European policy arenas—each with their specific vocabulary.4 Moreover, the concept of culture itself has been (and indeed, increasingly is) a tool for purposeful and powerful ideological rhetorics (ranging from populist nationalists, to neo-conservatives, to neo-Marxists) that seem to feed on political, market and sector interests and ideologies. Conceptions of culture have thus become entangled in ideological and political discourse and positioning.

But there is also a deeper issue at work. This has to do with circularities that have irreversibly become part of any cultural policy debate, since sociology and multi-cultural society have established the awareness that any judgement on cultural expressions, values or identities is inextricably bound to cultural bias.5 “Who is talking?” is now the first question that is put forward in any debate on cultural policy. With this rhetorical “axe” the debate on cultural policy is irreversibly split along cultural fault lines, instrumentalising the discourse on cultural policy.6

In the face of these challenges, this paper develops the idea that culture may be conceptualized as a communicative process, i.e., as imaginative or performative communication. The guiding hypothesis of this paper is that by building this new process-framework for the conception of culture, the debate on culture, cultural policy and the arts may find a new point of orientation, and some of the circularities and tensions in the debate (Drion, 2023) may be resolved or reframed.

Exploring this hypothesis, the paper takes off with a short introduction to the work of Niklas Luhmann on communication—as one of two possible avenues for grounding a new theory of cultural communication (to be distinguished from communication about culture or communication of culture).7 It finds that at the heart of Luhmann’s grand theoretical construction, an opening for the concept of a specific communication mode may be found, facilitating ambiguous communications. From this, the concept of cultural communication is drawn up. Annotating on Luhmann, the paper will then illustrate that this concept of cultural communication sits well with real-life observations on play (Schechner and Schuman, 1976), performative and subjunctive interactions (Fisher-Lichte, 2009; McConachie, 2015) and a societal “third space” where societal binaries may be left open or tried (Bhabha, 1994; Soja, 1996; Baecker, 2012). This specific domain of practice of suspended meaning8 is also the locus—albeit not the exclusive prerogative—of the arts.

Switching to a more practical perspective, the concept of cultural communication is then brought to bear to explore new perspectives for real-life policy development, circumventing the circularities embedded in de rhetorics of cultural policy, A short Practical frame is dedicated to the reflective framework of cultural encounter, putting cultural communication into practice for (arts-, culture- and social-) professionals, cultural organisations and policymakers – as recently carried out in Netherlands (Drion, 2018; Drion, 2022).

Over all, this paper may best be considered a tentative exploration. It covers a lot of ground, conceptually positioning a new concept. As such, it has its limitations, which will be discussed at the end of the paper, by confronting some alternative theories and concepts.

Theoretical frame

Systems and semiotics

Looking for descriptive (value-free) frameworks9 to scaffold a theory of cultural communication as process between people, two options immediately come to mind: semiotics (Charles Sanders Peirce)10 and systems theory (Niklas Luhmann). There are connections between the two frameworks (as indicated by (e.g.,): Maturana and Varela (1984), Bateson (2002), Hoffmeyer (2008), Deacon (1998) and Bausch (2001).11 Another study (Drion, 2023) will research these similarities in the context of cultural communication. This current paper is directed at the systems theory of Niklas Luhmann, whose work is of profound and still growing influence on sociology—and offers interesting applications in the theorising of cultural policy as well. Moreover, Luhmann’s work comprises a foundational meta-theory of societal communication, as such, any trial at conceptualizing culture as communication must, in one way or other, relate to it.

Society as communication

Luhmann’s work is focused on one thing: the construction of an all-encompassing theory of society as communication. Or, to put it more precisely: society as an amalgam of self-regulating systems with one single operator: communication. Loosely paraphrasing from his dense prose, two fundamental notions (as a sort of “truisms”) stand out at the heart of his theory. The first truism is that humans are “thrown” into the world equipped with mental faculties (psychic systems) that can never connect directly: we can never know for certain what other psychic systems think or feel: all we can ever do is: try to communicate—and try again. The second truism is that every imperfect trial of communication consists of selections as temporal events: we say this, not that. Luhmann then shows how these two simple facts spawn the most intricate and complex set of functionally stratified communication systems creating their own boundaries and rules: society.

Luhmann builds his encompassing systems theory by oscillating between the microlevel (of communication between psychic systems) and the macro level of social systems (society). He argues that both psychic systems and social systems must make temporal selections when they communicate, or more precisely: that communication is temporal selection.12

This notion of communication-as-selection entails that both psychic and social systems organise themselves in functional (selection-driven) ways: patterns of selections grow into functional social (or cognitive) units. Social systems (sociologist Luhmann does not say much on psychic systems, but emphasizes that they are indeed systems) are formed by the use of functional binaries. These binaries drive the formation of subsystems, like the binary “true-untrue” for the science system or the binary “legal-illegal” for the justice system. Society for Luhmann is the grand total of all of these self-regulating binary communication subsystems which he describes meticulously in several major works.13

Selection as distinction

Luhmann underpins his key-concept of binary selection with George Spencer-Brown’s Logic of Form (Spencer-Brown, 1969). Here his work does become very abstract, it requires exaination, as it is a central part of Luhmann’s reasoning to which this paper wants to annotate.

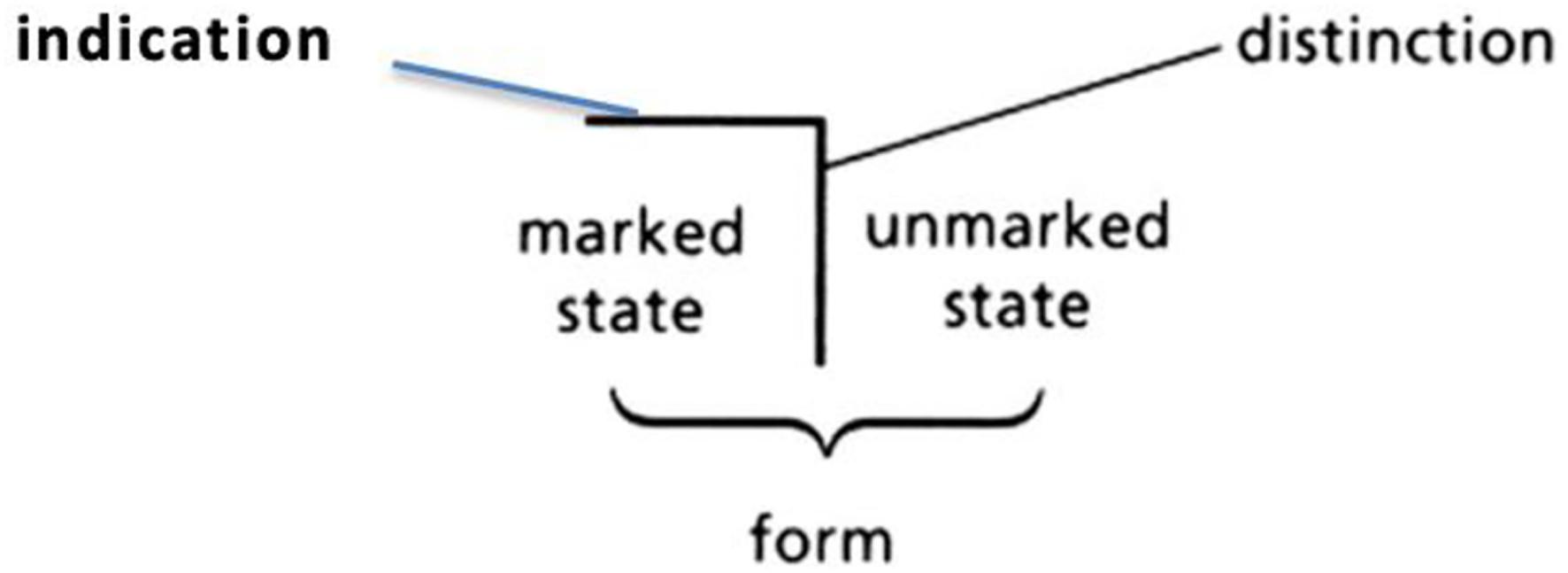

Spencer-Brown postulates that at the heart of any (temporal) act of selection lies a unity of distinction and indication, that spawns a form. For Luhmann this means that any communicative selection is at the same time both a distinction and an indication: by saying “this” and not “that,” both a distinction (between this and that) and an indication (this, not that) spring to life, are made simultaneously manifest—as a “unity of selection.” Spencer-Brown names this unity of selection: form.

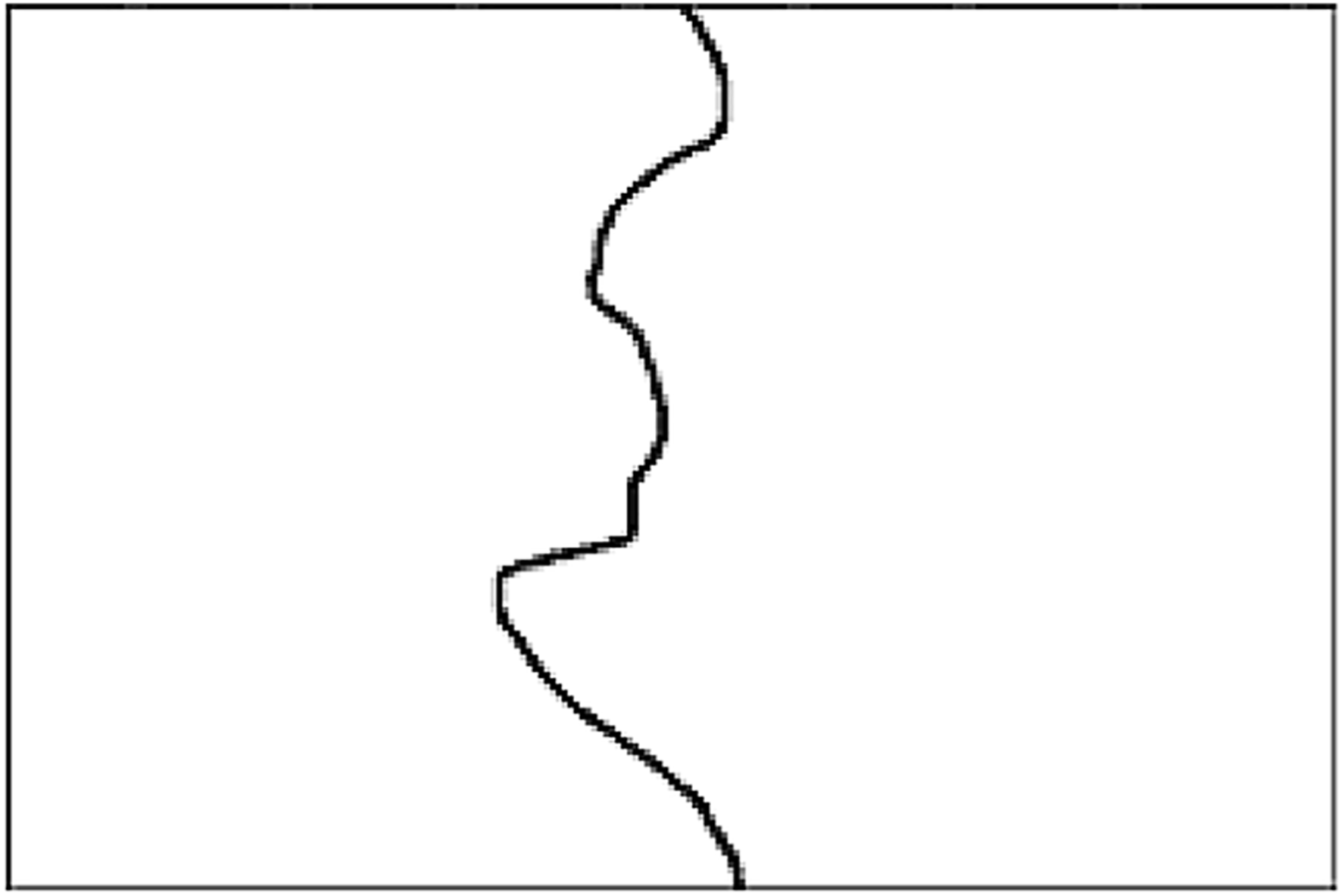

For Luhmann this is a crucial notion, as it depicts that every selection forms a “cut out” shape that not only indicates what is selected, but also indicates what is not selected (out of the range of alternatives at hand). In other words, the form spawned by selection exists as a shape that marks the difference between the selected and the not-selected (Figures 1, 2).

FIGURE 1

Selection (Spencer-Brown): “Marker” (unity of distinction and indication) Selects “Marked State,” creating form. (Source: author’s elaboration).

FIGURE 2

Form as Boundary. (Open source).

What is of importance here, is the notion that in Luhmann’s world communication is the basic operator of any social system, and selection (in the Spencer-Brownian sense of form) is the basic element of every communication. This means that any communication (and indeed any communication system) is a reduction to form, which allows for the unselected (out)side to be observed and remembered.

Structures and media

Observation, expectation and remembering are a key part in Luhmann’s social theory. Because communications are events that only exist in time, communications must be tried again and again. That is why, Luhmann says, grand structures and “media” continuously arise to facilitate effective communication and remembering: to make pre-selections, so to speak, that streamline communication. Luhmann positions these structures and media in society.

Luhmann does not claim that observation, expectation and remembering would not, also, be situated in psychic systems. As a sociologist, his focus is on society, that is: on communications, that weave patterns, forming societal processes of a specific kind (social systems) that in turn find ways that help to observe, expect and remember.14

Culture

How do culture and the arts fit into this grand concept of society? As for culture, Luhmann is quite clear that the societal organisation of observation, expectation and remembering cannot be a social system in and of itself (as it is not communication in Luhmann’s definition).15 Instead Luhmann introduces the term medium, which may here be taken to refer to a set of communication pre-sets or configurations (including language, values, structures) that provide the preconditions for enduring and effective communications within society. A medium is built up over time by the communications within a system, without being “seen” by the systems that use it. Although with much (uncharacteristic) hesitancy, Luhmann says this invisible medium is what may be called “culture” (Burkart and Runkel, 2004).

There is much to say about this, but it is clear that Luhmann does not thoroughly theorise culture as such and this leaves room for interpretation and amendments. Baecker (2012), Baecker (2013), Laermans (2002), Laermans (2007) and others have done just that, and commented that culture in Luhmann may be seen as a sort of reservoir on which all communications draw to facilitate the ongoing process of meaning construction. Indeed, this is more or less in line with what the common, anthropological definition of culture entails (see: Geertz 1973; Keesing 1990).

Art as a social system

In his conception of art as a social system Luhmann (2000) works “outward,” starting from the practice of creation. In accordance with his theory, Luhmann argues that every step in the formation of an artwork designates a temporal selection by the artist: “Here and now, I do this, not that”.16 Luhmann then states that every selection by the artist refers to the work itself. The binary that drives this selection in relation to the work is the distinction “fitting/not fitting.” The “selection process” (the conception of the work) goes on until the work is “done” – the point when there are no further selections left to improve the work.17

Luhmann then projects the same binary “fitting–not fitting” operating at the functional level of the social system of the arts: art as a social system “autopoieticly” reproduces itself by selecting fitting/non-fitting works. This must be taken in a paradoxical sense: what “fits” in the social system of art, fits because it does not quite fit, or in other words, in the social system of the arts, innovation “fits” (leads to continuation of the system) and imitation does not fit (is rejected, ignored or forgotten by the system).18

Notes

It is significant to note that Luhmann does not see the artwork itself as a dedicated communication. The work however does communicate by referring to itself as a product of selections by the artist. Each of these selections yield form in the sense that they also indicate the non-selected options in relation to the work.

Luhmann mentions (in passing) that a particular prerequisite must be fulfilled for the artwork to communicate (in the Lumannian sense): it must, first of all, be introduced as artwork so that it may be interpreted as such (and not, e.g., as an “ordinary” soapbox or a pissoir).19,20 This is important for where this paper is going, because it leaves some space within systems theory to think of communication modes. I will come back to this in relation to play.

The second note is that Luhmann separates the “communication of the artwork” from the communication about art, which he designates as the “social system of art.” This is important because it leaves some space within systems theory to think of communication modes on the level of societal phenomena.

Wrap up

Luhmann’s social systems theory may be seen as an ultimate description of the systemic necessities of the process of communication. As such it may provide a strong and credible framework for a theory of cultural communication. There are however, as noted, some major issues to be addressed. The first is that Luhmann’s theory does not provide any clear definition of culture-as-process: Luhmann seems strikingly hesitant on the subject of culture (Burkart and Runkel, 2004). The second is that his description of the process of creation of the art work (as communicative artefact) does mention “a special kind of communication”21 in relation to the arts, but this “special kind of communication” is not theoretically developed in relation to culture. Thirdly, Luhmann seems to describe the social system of the arts in terms of communication about art and not primarily in terms of communication through (or with) art. Finally, although not mentioned above—but mentioned by others—the work of Luhmann leaves some gaps when it comes to embodiment and emotions as locus or driver of (inter)personal and societal processes, actions and experiences (Ciompi, 2004; Ciompi and Endert, 2011; Damasio, 2018). These issues may be addressed if the description of culture is more precisely taken apart, in particular in relation to ambiguous communication.

Exploration

New territory: The process of culture, culture as process

A deep and significant (but often hidden) aspect of the use and definition of the term “culture” is the distinction between the process of culture (i.e., the way “culture” influences or determines the interactions in society) and culture as process (i.e., as properties of communication). Put in other words: the difference between the process definition of a noun or a verb.

The use of culture as a noun in a process-definition of culture focusses on what culture is through what it does, i.e., the way culture as a set of (e.g.,) values, behaviours or artefacts (or as “reservoir of symbolic meaning” (Laermans, 2002)) mutually interacts with the processes that happen within and between people (or within and between structures or organisations). This use of the term culture is very well developed albeit contested and stratified in different schools of thought.22

With the use of culture as a verb, a process-definition of culture shifts focus to what it entails to culturally communicate. This use of the term culture (as process-distinction of communication) has not yet been theorised. It does however resonate with Luhmann’s description of the creation-process of artworks, as well as with the concepts of bio-systems and cybernetics (Deacon, 1998; Bateson 2000) and with some stands in sociology (Laermans, 1997; Baecker, 2012), art-theory (Van Maanen, 2005) and play-theory (e.g., McConachie, 2015). It is my aim to bring these strands—in a provisional way at least—together within the basic framework of communication theory, extending on Luhmann’s suggestions on a special “kind of communication” that comes with the creation and interpretation of art. I will develop this by connecting the everyday practice of ambiguous communication with subjunction (such as in play, storytelling, irony and the arts).

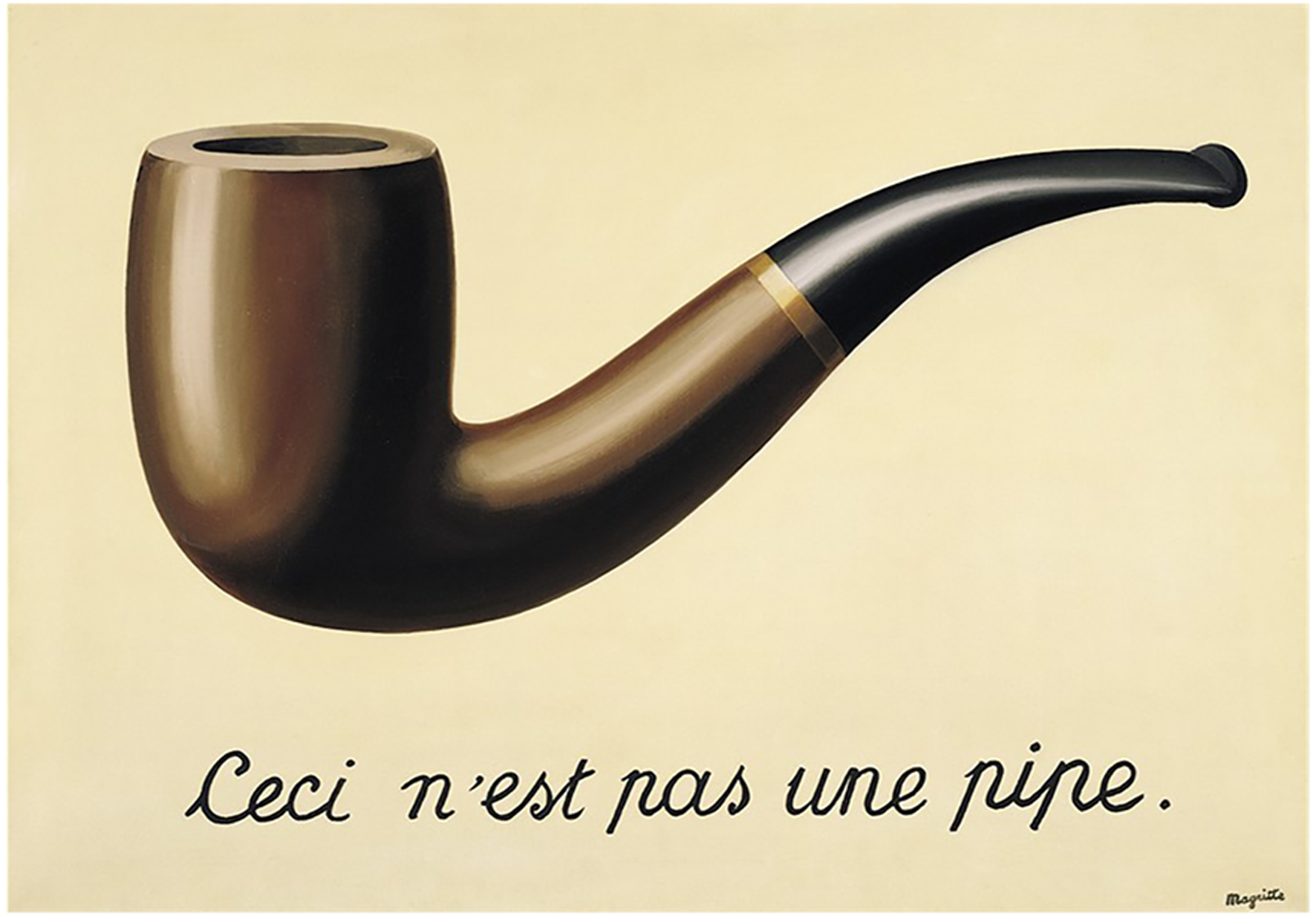

Communication mode

The suggestion I am making then, is that cultural communication may be conceptualised and theorised as a designated mode of communication. Let me illustrate this with an example, elaborating on Luhmann’s suggestion that for any artwork to function communicatively (as an artwork), it must be introduced and recognized as such. The communicative “mode” that designates such a switch from “reality” to the space of purposeful “non-reality” is playfully thematised by Magritte in his famous painting Ceçi n’est pas une pipe, which points to the self-evident difference between literal and imaginative interpretation. Ever since the arrival of abstract and conceptual art (like the ready-mades of Duchamp or Warhol’s Brillo Box) this distinction between the real and the imaginary has been irreversibly established—and consequently been thematised (“re-entered”) in art (Figure 3).

FIGURE 3

La trahison des images (René Magritte, 1928–1929). (Open source).

The point I would like to make is that this obvious communicative switch from reality to an imaginative non-reality mode is not confined to the arts and is indeed much more widely practiced in everyday communication than we perhaps might realise. To illustrate this, I will turn to the work of Bateson and McConachie on play and storytelling—and tie these back to culture and the arts.

Play

There are two interesting parallels between the “artistic” mode of interpretation (this is not a pipe, this is not a Brillo box) with other, quite common communicative settings: social play and storytelling.

Gregory Bateson famously stated that for any social play (human or animal alike) to take off, a meta-communicative signal “this is play” is required (Schechner and Schuman, 1976; Mitchell, 1991). Only if the signal is picked up, a playful communication mode (my term) may be established and playing may progress unimpeded by any misunderstandings that what takes place is actually “for real.”

It is obvious that there are many sorts of play and many definitions of play,23 but for me it is significant these all have in common that some form of open-endedness is essential to playing: playing is, in a deep evolutionary sense, always a designated, staged form of trying.24

Bruce McConachie (2015), Erika Fischer-Lichte (2008), Fischer-Lichte (2009) and others have suggested that play and storytelling (or more general: performance) are closely related25 as both presume (and establish) a specific mode of communication: subjunction. Subjunction is the communicative transfer of “is” to “were” (or in other words, from a reference to reality to an imagined “as if” or “once upon a time”). This transfer opens a specific mode of communication: a playful performance and interpretation of a “reality” that is not-real, which of course is the hallmark of all art—but, as I just now put forward, not limited to art.

These switches from the real to the not-real are similar between play and performative acts, but the question remains whether they may indeed be the same in terms of communication?

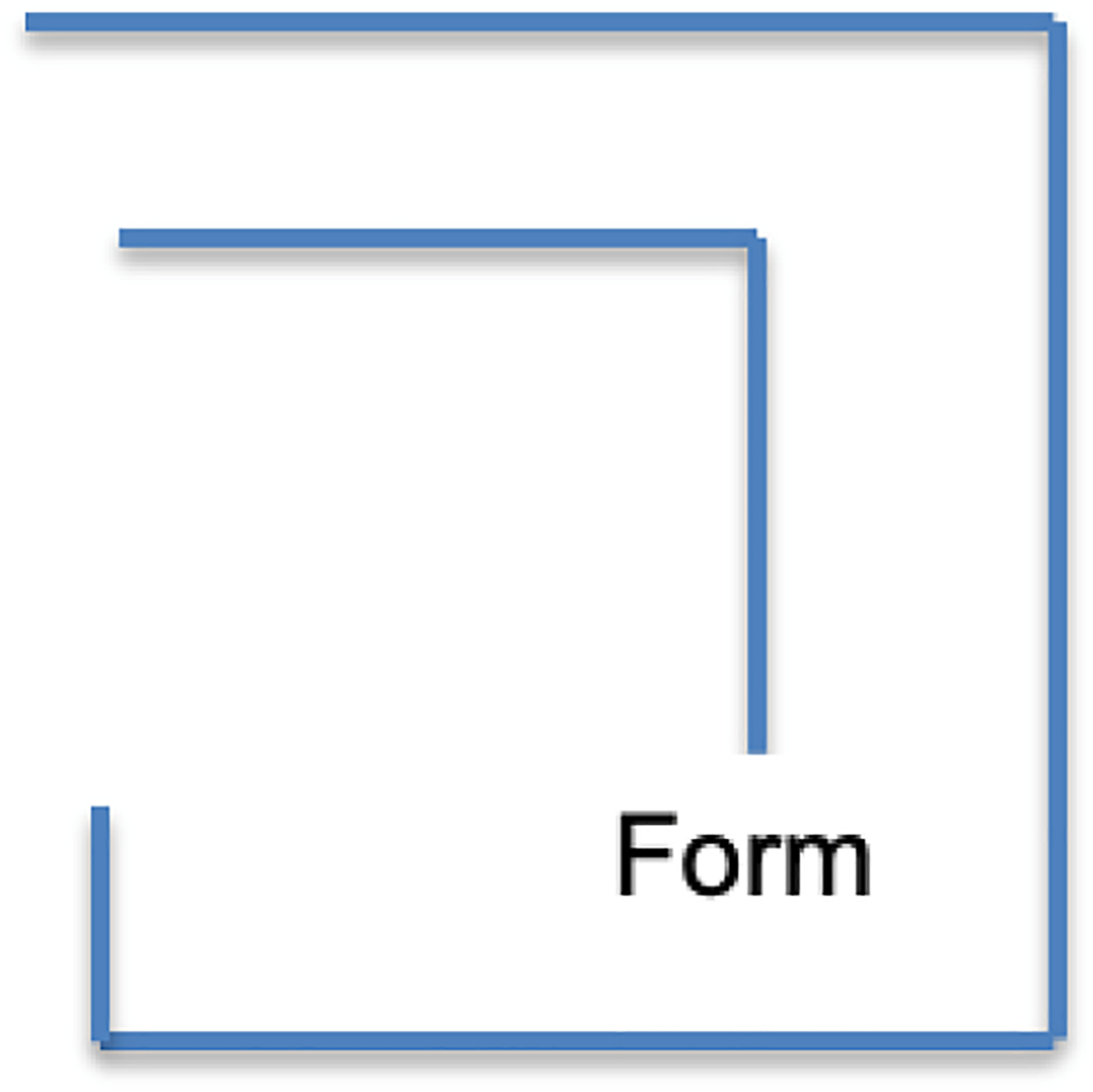

Back to Spencer-Brown: The re-entry of form into communication

What happens “communication-wise” when we switch into this subjunctive mode of communication? How could this be reconciled with the concept of selection (i.e., reduction to form) as the basic unit of communication? I would like to suggest that the imaginative communication modes of subjunction and play have in common that they both thematise ambiguity. Put in the language of Spencer-Brown: an ambiguous communication mode is the re-entry of the form (i.e., the shape between the indicated and the not-indicated) into the marked state, as a thematised ambiguity.26 (Figure 4).

FIGURE 4

Re-entry of form into the marked side of selection (The operation of re-entry is indicated by the outer hook; see also Figure 1.). (Source: author. See also: Baecker, 1993).

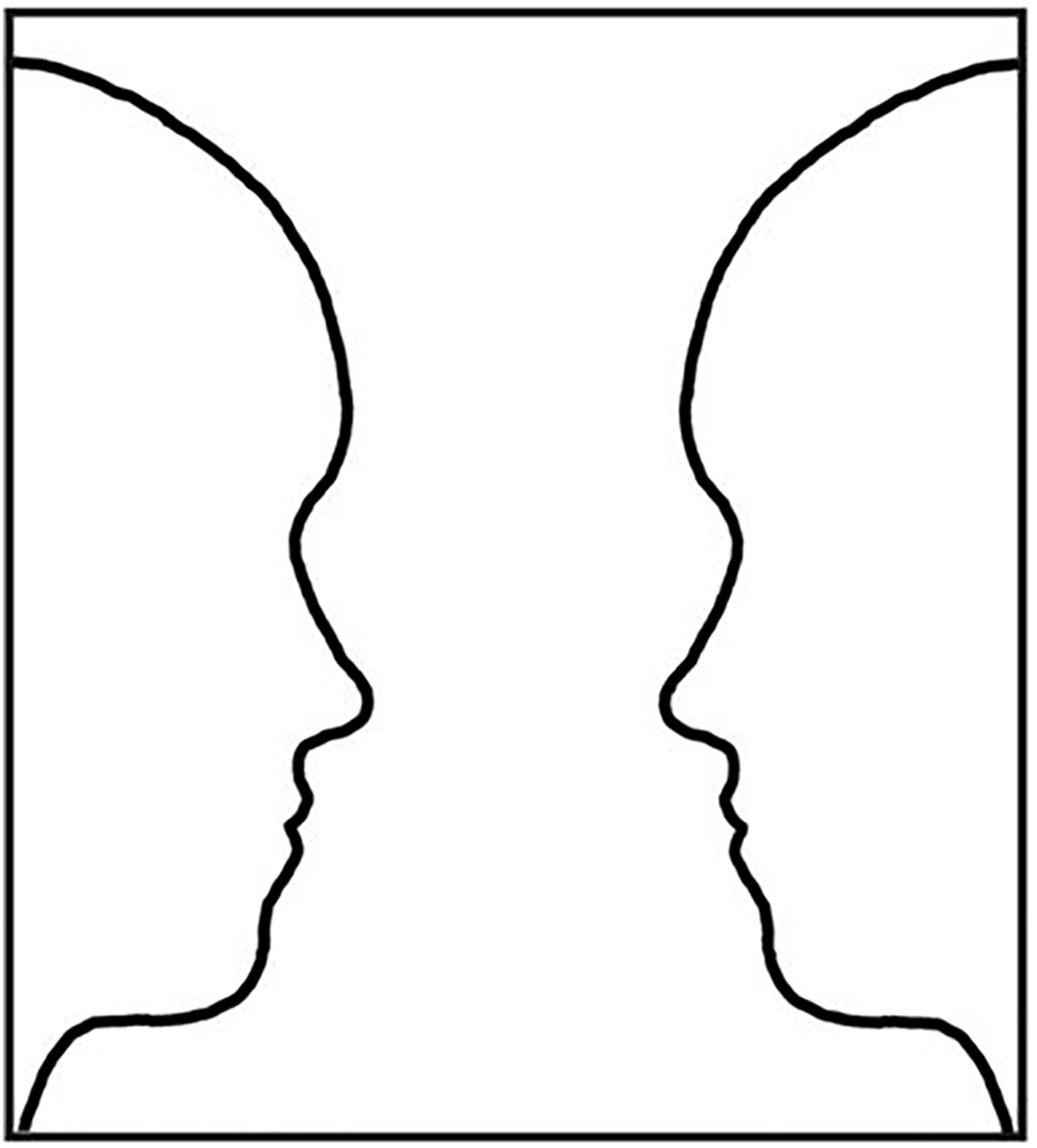

This may seem very abstract or theoretical, but it may also be seen in an everyday perspective. When communication switches to an ambiguous mode, the difference of what is indicated and what is not indicated (the Form) becomes part of the communication as ambiguous meaning. As such, it “lives” on for as long as the ambiguous communication mode is continued. A “flippety image” or “Kippbild” (Vilc, 2017) is an example of this oscillating meaning (Figure 5).

FIGURE 5

Form as ambiguous meaning. (Open source).

Proposition

This brings me to the centre of my argument. It is my proposition that an actual, distinct (and widespread) open ended communication mode exists in society, between people, distinguished by the selection of thematised ambiguousness. Annotating to McConachie I would suggest that from the “root” of this common ambiguous communication several different practices “branch off”: play, playful ambiguous communications (such as humour and irony), storytelling, all expressive performances—and art.

Looping back to Baecker’s and Laermans’ (noun-)definition of culture as a reservoir of shared meaning, I propose to call this imaginative, ambiguous communication mode: cultural communication, because it is, per saldo, thematising the playful “what-if” in the domain of shared meaning. Or put differently: seeing culture (as a noun!) as a reservoir of shared meaning (Sinn) (Laermans, 1999; Laermans, 2002; Baecker, 2012), ambiguous communication may be the way this reservoir is continuously, playfully opened for association, reflection, subversion and growth.

Positioning

Culture, communication, otherness, play and space

Among his many other interpretations of and reflections on Luhmann’s work, Baecker (2012), Baecker (2013) puts forward that culture may be placed in systems theory as a Tertium Datur: a societal “third space” where the “opposition” to the functional binary way Luhmannian communication systems operate, resides. For Baecker then, culture produces the “third values” that facilitate a vocabulary that the differentiated social systems may share. Although Baecker’s elaborations of Luhmann’s theory suggest a similar direction as the one that I am proposing, his reasoning seems “tied” to the process of culture (as a noun). Although this obviously deserves much more attention (see also: Discussion), I will now simply suggest that the concept of cultural communication may provide an explanation of how this societal “third space” is linked to the process of communicating.

It is interesting to note that, although formulated in a completely different context, the concept of playful undecidedness has parallels with Homi Bhabha’s Third Space (Bhabha, 1994) as a space where (in a colonial context of cultural domination), dominant cultural expressions, identities and clichés are paraphrased, ridiculed and transformed. This in turn has strong relations with Victor Turner’s concept of liminality as a phase of becoming, between an old and a new equilibrium, state or identity (Turner, 1982). And last—but not least—it may be associated with Edward Soja’s (urban) theory of Thirdspace, as a space of limitless options, radically open to otherness (Soja, 1996).

These conceptions of space have in common that they envision a communicative mode of imagining, undecidedness, openness and creativity: when binaries lose their urgency and conflicts and identities are liquified through imaginative interactions. They also have in common that the term “space” is not used in any physical sense (although place as physical space may be an important context), but as a locus created by an associative and communicative interaction, as communications (including embodied behaviours) set themselves in a mode of ambiguity and performativity, opening new horizons for shared meaning and sense-making.

In Netherlands, Hans van Maanen (Theatre Studies) has suggested that artistic experience can only come about when the interpretation “schemata” of the subject are sufficiently challenged, i.e., when the confrontation with an artwork sparks interpretive surprise, wonder or (as Pascal Gielen later put it) dis-measure (Gielen et al., 2014). This notion too, comes close to my propositions on cultural communication, although Van Maanen (2005) seems to speak mainly in relation to the arts.27 In addition, I would suggest that the experience of dis-measure that Van Maanen–I think justifiably so–puts central to artistic experience, may find its pendant in a specific communication mode that is of a much wider practice than the arts as such.

This short positioning would not be complete without Johan Huizinga. In his seminal work Homo Ludens, Huizinga (1938) famously places play at the root of all culture. “Behind any expression of the abstract lies a metaphor and within any metaphor there is a wordplay,” Huizinga writes. In this way, humanity “continuously creates a second, imagined world alongside that of nature” (…) “Great activities of cultural life” (including religion, law, economy and science) are rooted in a “soil of playful activity” (sic). Huizinga does not theorise his thesis, but richly illustrates it with an abundance of examples from history and anthropology. Annotating, I would suggest a theory of cultural communication may help to fill in Huizinga’s thesis.

In the field of cognition and evolution strong clues can be found that cultural communication (in the sense of the playful thematisation of the what-if in the domain of shared meaning) may be an important factor in the evolutionary development of humans and society. We need ambiguous ways to try meaning, on both the interpersonal and the societal level. Vygotsky (1996), Damasio (2018), Donald (1991), Tomasello (2000), Dissanayake (1974, 2012), Van Heusden (2009), Van Heusden (2010) and many others have theorised, researched and documented this convincingly in the context of human development, cognition, interaction, cooperation and evolution.

To round this short positioning off, it is worthwhile to reiterate that inspiring connections may be found between systems theory and semiosis (the production and comprehension of signs). The concepts of Eco (1978), Eco (1988) and Lotman (2011) on sign systems, media and the “semiosphere” are strongly related to the process of sense-making, imagining, culture and the arts (Machado, 2011; Tarasti, 2015; Thibault, 2016; Zerubavel, 2018).

(A short discussion of culture, power-reproduction and ‘blind spots’ can be found in paragraph Discussion and limitations.)

Policy perspectives

The guiding hypothesis of this paper is that a process-conception of culture may offer a new point of orientation for cultural policy and may resolve some of the circularities and tensions in the current (identity driven) debate. Annotating on Luhmann’s theory of society as communication, this paper presented a process-conception of culture as a playful ambiguous communication mode (designated as cultural communication or “culture as verb”). It then associated this concept with performative interaction, undecidedness and societal “third space,” and pointed to related strands of thought on art, culture, cognition and semiosis. So, what changes does this bring to the table for cultural policy?

The first (and most obvious) change would be that a policy directed towards cultural communication will no longer to be grounded in, or (primarily) aimed at the conservation, dissemination or production of specific values, identities or artefacts—as traditional cultural policy is. Instead, it will be grounded in, and aiming at the interactional processes by which values, identities or artefacts come to life. In that sense, such a policy is democratic in the deep layer that it is not (primarily) directed at representation of solidified identities, values or artefacts in the public sphere, but at the (imaginative) processes by which identities, values and artefacts mediate, liquify and change; essential for an open society (Ignatieff and Roch 2018; Zerubavel, 2018). By grounding in this deeper democratic layer, cultural policy may find a way out of the circular “legitimacy stalemate” pointed out above (see: Introduction), because it can no longer be instrumentalized or “hijacked” by identity rhetorics. (See also: Discussion and Limitations.)

Elaborating on this, it is interesting to note that it was Gregory Bateson (who published extensively on systems, cognition, cybernetics and play) that coined the term “schismogenesis” for the mechanism of cultural opposition: although culture may remain “invisible” for anyone “inside” it, cultural awareness will urgently come to the surface when confronted with other cultures: every culture will define itself in terms of otherness. Bateson (in Schechner and Schuman, 1976) sees the dynamics of this cultural “schism” as a natural function of human society. However, feelings of fear and resentment lie close to the surface and can easily be manipulated by populists and activists (Ciompi and Endert, 2011). Needless to say, these mechanisms have since Bateson’s time (he wrote on schismogenesis in 1935) become exponentially more virulent with the rise of social media and online tribalism.28

In these polarized times then, it seems of importance that other ways of cultural awareness and growth (other than through cultural opposition) are at the disposal of society. It is at this point that a new cultural policy, directed at cultural communication, may play a role.29

A second change that a process-directed cultural policy may bring about, concerns the role of artists and the arts. It has often been said that artists or the arts should not claim exclusivity for the societal enhancement of creativity and imagination (or, for that matter, for cultural participation, or for social “bonding” and “bridging”),30 as there are many other processes in society that may bring about these qualities in people’s lives. The concept of cultural communication may help to put the issues concerning the role and surplus of artists and the arts in a wider and deeper perspective.

If we see cultural communication as a mode of deliberate ambiguous communication (thematising the playful subjunctive “what-if” in the domain of shared meaning), the role of arts and artists may come to light as a specific depth in this communication mode. Artists and artworks renew and update the expressive vocabulary (“form-languages”)31 in and of society, creating inspiring, provocative or wonderous signposts in the “third space” of cultural communication. To be able to do so, artists must also be the keepers and disseminators of the specialist vocabulary of their discipline and the sets (passed down and continuously developing) of integrated skills that may bring that vocabulary to life.

From this vantage point artists can confidently unfold their role and position in society (in the Luhmannian sense of a communication system), and transparently balance the necessity of their artistic skills and autonomy with the necessity of their communicative embeddedness; proudly conscious of the fact that their work will find full significance in the playful context32 of cultural communication and cultural encounter (see also: Practical frame).

Combining these two observations, cultural policy design may gain new perspective. Two dimensions can then be functionally distinguished: the dimension of the width and the dimension of depth of cultural communication.

• For the maintenance and facilitation of the width of cultural communication, policy can be directed towards the capability33 in and of society to arrange cultural encounters past the cultural “walls” of schismogenesis and power reproduction.

• For the maintenance and facilitation of the depth of cultural communication, policy can be directed towards the capability in and of society to arrange cultural encounters beyond the vested vocabularies (form-languages).

This “third way” of policy formation may have far-reaching implications, to be discussed and explored.

In the Practical frame (below) a trial set-up in Netherlands is presented, serving as a prelude to such explorations and discussions. In anticipation, a key finding of this trial may be of interest here: a policy directed at the arrangement of cultural encounters would have to be adaptive in a deep democratic sense, as cultural communication only springs to life in a free setting. Traditional policy elements (input, output, outcome) will have to be re-designed in a process-vocabulary for the facilitation, collaboration, and evaluation of cultural encounter. In a midsized “new-town” in Netherlands this policy re-design was democratically rolled out with the participation of the broad cultural field, triggered by the collectively shared challenge to facilitate cultural encounters for everyone.34 This yielded a new collective vision for cultural policy for a period of 8 years, and major revisions of funding and collaboration. In the Practical frame (below) some further remarks are made on the development of specific tools for policy design and collaboration.

Discussion and limitations

As pointed out in the Introduction, this study is a tentative exploration of new territory, and as such is limited in its scope and reference. Below, these limitations will be discussed in the context of the tensions between Luhmann’s theory and the conceptualisation of cultural communication as a basis for new cultural policy.

Luhmann’s grand theory of society as communication is as huge as it is dense, and it develops a radical (Moeller, 2006, Moeller, 2011), highly specialized and completely original vocabulary. Moreover, Luhmann’s theory is highly consistent: it does not tolerate “cherry picking“ or ad-hoc changes (Blom, 1997; Laermans, 1999). How does this relate to the propositions developed in this paper?

By connecting and annotating to this central point of Luhmann’s theory (i.e., Spencer-Browns unity of indication and selection) this article suggests an opening for conceptualizing an ongoing selection of ambiguity as a dedicated communication mode. As such, it does not dispute Luhmann’s grand theory or any of its implications; it sits beside, and in dialogue with, Luhmann’s great framework. The paper explores this position and is, needless to say, very much open for further discourse.

That said, as stated at the end of Theoretical Frame, there are tensions that need to be addressed when referring to Luhmann’s system theory in the context of cultural policy. The first tension addressed in this paper is that Luhmann is hesitant about the definition of “culture” within his grand theory. Several authors (Burkart and Runkel, (2004), Baecker, 2012; Burkart and Runkel, (2004); Laermans 2007) have pointed to Luhmann’s hesitancy, and have made suggestions for elaboration. This paper hooks on to these elaborations from the angle of cultural communication, drawing the preliminary conclusion that the concept of cultural space may perhaps form an interesting and viable bridge. However, the positioning of cultural communication in relation to cultural space on the one hand and system theory on the other, definitely deserves further exploration.

The second tension addressed in this paper is that Luhmann has a very specific view on the way art functions as a social system in society. In Luhmann’s view, artworks communicate in a functional system, driven by the paradoxical binary “fitting—not-fitting”. The theory of cultural communication presented in this paper places at the heart of cultural communication (which includes artworks but is not limited to art) a non-binary (!) ambiguous communication mode. In Luhmann’s world this mode would have to be theorised back into a binary fashion (ambiguous—not-ambiguous?). This also, deserves further reflection.

The third tension is that Luhmann’s world is, at first glance, not very “physical” or “immediate.” Psychic systems and the body are in Luhmann’s view “structurally coupled” and “irritate” each other, but there seems to be little room for direct physical interaction or immediacy, which seems intuitively essential for play (e.g., Winnicott, 1971; Sutton-Smith, 1997), performativity (e.g., Fischer-Lichte 2008) and cultural communication as presented here. This tension has not been addressed directly in this paper; I plan to study this further in relation to semiosis and living systems.

A fourth tension, mentioned here for the first time, may be that Luhmann actually does speak of a “doubling” of meaning, but does so specifically in relation to mass-media. Mass-media construct reality, or explore possible realities, e.g., in a story or a sit-com (Luhmann 1997). Through mass-media, “realities can be constructed and constructions can become realities” (Luhmann 1997). However, Luhmann makes these remarks in the light of a Luhmannian system (of mass-media), driven by the binary “new information—old information.” In contrast, the theory of cultural communication presented in this paper draws on the selection of ambiguity in a dedicated communication mode. The relation between these two concepts of “doubling” needs further reflection.

Blind spots

Any choice of frame creates its own blind spots, as Luhmann famously theorises. From the point of view of this article it is important to note that the framework of ambiguous communication (as indeed in Luhmann’s system theory) does not see power-relations as communication. It states that cultural communication is tied to a communication mode that may bring values, identities and artefacts into play between people. Cultural policy should then be directed at the width (i.e., past the walls of power relations) and the depth (i.e., renewal of form-languages) of cultural communication. In other words: the theory of cultural communication presented here does not deny the existence or importance of power-reproduction or exclusion in relation to cultural policy; it sees this as circumstance to be addressed by flanking policies. (See also below.)

Power and power reproduction

In that regard, the work of (e.g.,) Bourdieu (1984), Bourdieu and Passeron (1990), Ranciere (2000), Ranciere (2010), Braidotti (2005) and Gielen et al. (2014) must be mentioned. Although mutually different in many aspects, these and other authors have in common that they place the reproduction of power-relations through the cultural reproduction of meaning and value central in their work. This leads them to a specific analysis of society and culture, and consequently to specific (although quite divers) analysis and (perhaps idealistic) design of cultural policy. These analyses are, no doubt, of significance in the debate on cultural policy (where indeed they find growing influence and support). I would not want to oppose their inclusive objectives in any way, although elsewhere (Drion, 2023) I do propose that cultural policy on the basis of identity may well be fundamentally flawed. At the current point in time I would however suggest (1) that a theory of cultural communication may explain the dynamics and evolution of culture on a deeper communicative level, and (2) that a theory of cultural communication may crucially show the fluidity of cultural communication as an intrinsic dimension of society (in the Luhmannian sense), which interacts with the structural and power-reproductive mechanisms of society, and must therefore be included in, and be the deeper goal of, any cultural policy.

Ecosystems, cultural democracy, capability and commoning

Cultural ecosystems are currently at the forefront of the discourse on cultural policy, governance, participation and democracy.35 It is important to note that the term appears in two conceptually different strands: a representational and a participatory strand.

In the representational variant, cultural ecosystems are conceptualised at the institutional level, as a set of more or less formal facilities that need to be opened for democratic representation of all cultural groups, both formally (as diversity) as in their programming and modus operandi (as inclusiveness) (Hadley and Belfiore, 2018; EU, 2021; Hadley, 2021), In the participatory strand, cultural ecosystems are seen as a democratic process-approach to inequality and exclusion. It is interesting to note that two variants of this particular strand are emerging: cultural commons (Volont et al., 2022) and cultural capability (Wilson, 2017). Although there may be comments on the theoretical underpinning (Drion 2023), both of these participatory strands relate well to a frame of cultural communication: commoning as a strategy for facilitating cultural communication and encounter (see Practical frame); cultural capability as a participatory strategy for talent-development and supported cultural autonomy (Wilson and Gross, 2018).

Further study

As may be clear from the above, further study is beckoning on a whole range of subjects. For the further development of a full-blown theory of cultural communication, critical analysis from system theory is very welcome, as well as corroboration by a further study of semiotics in relation to meaning, systems and ambiguity. Some promising leads may be found at the crossroads between the work of Lotman (2011), Eco (1978), Eco (1988) and Fischer-Lichte (2008), Fischer-Lichte (2009) on culture, the arts and semiotics, and in the work of Vygotsky (1996), Donald (1991), Damasio (2018), Van Heusden (2009), Wheeler (2015) and others on the relation between biosemiotics, semiosis, cognition, culture and evolution.

On the practical side, fruitful crosslinks may be found in the actual discourse on cultural capability, cultural ecosystems, cultural democracy, Thirdspace, arts education, social resilience and inclusiveness. The reflective framework presented in the Practical frame (below) may serve as a perspective for arranging cultural encounters—as basic unit of cultural practice, organisation and policy. Extensive research is needed to follow the actual impact of the method, and the way a shared vocabulary may work to arrange and align practices, organisations and policies. Nonetheless, the framework seems (as such) a step forward, as a heuristic operationalisation of what actually happens in cultural encounters has, so far, been missing.

Practical frame

How can we arrange cultural encounters past the ‘walls’ of power reproduction and schismogenesis? Or put differently: how can we open the concept of cultural communication to the real-world practice of actual activities, organisations and policy?

In the Netherlands a two-year trial was set up, aiming to find a practical approach for cultural communication, by heuristically modelling cultural encounters. The trial was made possible by FCP (the Dutch national fund for cultural participation) and was supervised and hosted by LKCA (the Dutch national centre for expertise on cultural education and participation); six professional organisations were involved in nine separate set-ups.

Key notions

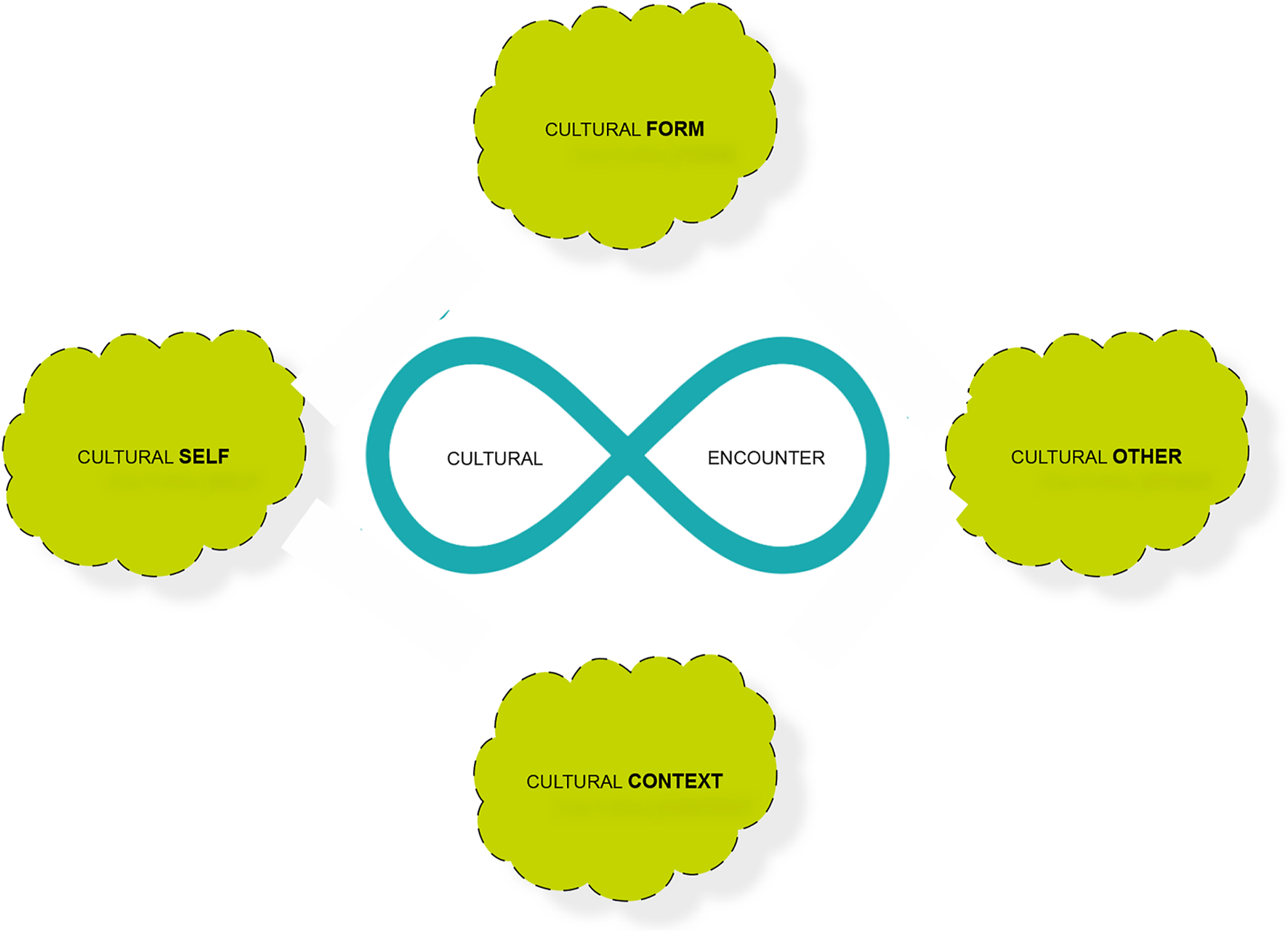

The trial was built around the tentative hypothesis that in a cultural communication mode four heuristic elements (cultural nouns) may be in play: cultural self, cultural other, cultural form and cultural context. The reasoning behind this is straightforward: if cultural communication is indeed a specific communication mode happening between people, a cultural self and a cultural other must be brought into play, spawning form that can only makes sense (Luhmannian “Sinn”) in context.

It is crucial to emphasize that this model is not referring to “actors” or “agency” in any way. It heuristically models a mode of communication (as such, between people) as a self-generating process. The heuristic modelling has the specific purpose of opening cultural encounters for professional observation and evaluation.

The term “cultural” in this model may need some clarification. In this paper, a distinction was made between ‘culture as noun’ and ‘culture as verb’. In the model presented above, the process of cultural communication (i.e. the point where culture becomes a verb) is represented by the “infinity sign” (or lemniscate) in the middle. The heuristic elements surrounding the process may be seen as “bearers” of symbolic meaning, identity or values, that are brought into play when a cultural communication mode is present (Figure 6).

FIGURE 6

The heuristic model of cultural encounter. (Source: author)

Positioning

In the context of this trial the term cultural capability was adapted in the Netherlands from the seminal work in the UK (Wilson, 2017; Wilson and Gross, 2018; Gross and Wilson, 2020) and consequently developed in the specific direction of Cultureel Vermogen36 (Drion, 2018, 2022): the capability in and of society to culturally communicate. Cultureel Vermogen (CV) proposes a dedicated model for opening cultural encounter to professional, organisational and policy design and evaluation. The model is a tentative proposition, developed over a series of dialogues with specialists in the field of cultural education, participation and policy.37

The working hypothesis of CV is: cultural encounters may be arranged by connecting the four heuristic elements into “strong” practical arrangements - that touch on both the depth and the width of cultural communication.

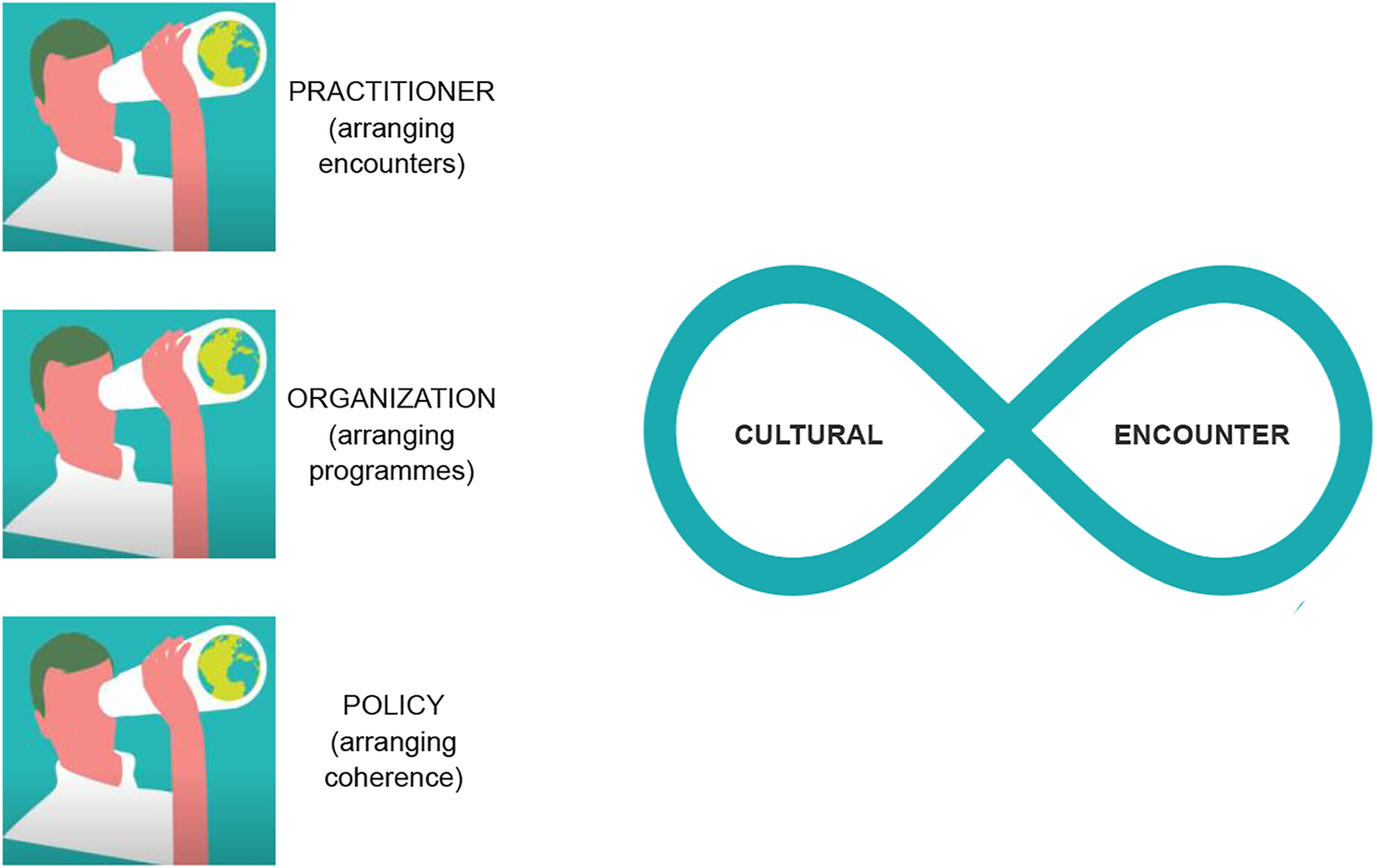

Levels of arrangements

Three levels of operation can work together to bring these arrangements about: professionals (arranging encounters), organisation (arranging programmes), policy (arranging coherence).

For each of these levels, dedicated proto-tools were developed helping practitioners, organisations and policymakers to collaborate – using a shared vocabulary. The tools will become available in the summer of 2023 (Figure 7).

FIGURE 7

Three levels of operation. (Source: author)

Remarks on future developments

The findings of trial setup of Cultureel Vermogen were presented in a conference in May 2022 in the Netherlands. A platform for further development is under construction. (More information: https://www.lkca.nl/categorie/thema/cultureelvermogen/).

Statements

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

The author confirms being the sole contributor of this work and has approved it for publication.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank everyone who in the past years have contributed to the ideas expressed in this paper, especially the many friendly co-readers and my PhD supervisors at the University of Groningen. This paper could not have been written without their support.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Footnotes

1.^Listed here as ad hoc findings by the author.

2.^The current discourse on cultural democracy (or views on the democratisation of culture) will not be explicitly discussed in this article. See also: Drion 2023 (forthcoming).

3.^See, e.g., Belfiore and Bennet (2008), Belfiore (2014).

4.^See, e.g., Drion 2023 (forthcoming).

5.^See, e.g., Eagleton (2000) or Bauman (1999), Bauman (2011).

6.^See Drion 2023 (forthcoming).

7.^See Carbaugh (2012) for a short overview of four ways in which culture may be theorised as communication.

8.^In this paper the term “meaning” indicates the Dutch “betekenen” or the German “bezeignen” which translates roughly to “signs that make sense.”

9.^Value free as in neutral process-theory.

10.^See: Peirce and Fisch (1986).

11.^Notably in the perception that difference is a basic condition for information to “appear” and to be handled between (or within) systems. As Bateson famously put it: “information is a difference that makes a difference.” Systems can only perceive differences; systems operate on differences.

12.^Luhmann famously defines communication as a three-fold selection: selection of utterance, selection of information, selection of understanding.

13.^In particular, ten systems can be enumerated: political systems, economy, science, art, religion, legal systems, sport, health systems, education and mass media (Roth and Schütz, 2015). These are autopoietic systems, operationally closed, and each has a specific binary code that includes or excludes an operation (Appignanesi 2018).

14.^This part of Luhmann’s theory has deep philosophical and methodical implications, such as his systemic “blind spots” which we must leave aside here (see paragraph: Discussion and Limitations).

15.^Luhmann opposes Parsons’ action theory. See Luhmann (2013).

16.^Of course, these selections are not per se “conscious” or “rational”; they will, at least in part, be embodied and intuitive. See, e.g., McConachie (2015) and Johnson (2007).

17.^There will obviously be different manifestations of this in material and performative art-forms.

18.^See Luhmann (2000) 118. Cf Gielen et al. (2014); Van Maanen (2005).

19.^See Luhmann (1987: 105) on “registering form as medium.”

20.^Here Luhmann seems to introduce some form of meta-communication into the communication of art. I will elaborate on that when I introduce the term communication mode.

21.^ Luhmann (2000) 26.

22.^See: e.g., Eagleton (2000).

23.^See: e.g., Huizinga (1938), Caillois (2001), Sutton-Smith (1997), Henricks (2015), Gadamer (1993).

24.^A significant difference between play and game should be highlighted here: a game will usually have an ending related to rules, play may not; a game needs to be played, but playing does not need a set of a priori rules per se. See also: Upton (2021). See also: Baricco (2020) on games, digitization and culture.

25.^Indeed, for all of these forms the word “play” is used.

26.^For an comprehensive introduction to Spencer-Brown in relation to Luhmann, see: Baecker (1993), (in German). For a lighter form, see: Baraldy (2021).

27.^Although in this context challenges may also reside in new information, revelation of identity, emotional content or new context/place. See: Van Maanen & Van den Hoogen in: DeBruyne and Gielen (2011).

28.^See also: Burkart and Runkel (2004) and Baecker (2012) on culture, opposition and middle ground (Tertium Datur).

29.^There are, of course, many other valuable approaches to this problem: the claim that art and artists act as “mirror” or “consciousness” of society is obviously one; another may be the growing interest in the education in culture (see, e.g., Van Heusden 2010); a third may be the growing attention to inclusion, cultural rights and participatory practices.

30.^See, e.g., Otte (2015).

31.^Drion, forthcoming.

32.^See also: Gadamer (1993).

33.^See: Nussbaum (2013). Nussbaum’s capability approach relates to the freedom people have to do and be what one has reason to value. In relation to culture and democracy this has been adapted by Wilson & Gross towards cultural capability: the freedom people have to recognize and explore what they have reason to value. For Drion et al. cultural capability relates to the capability in and of society to culturally communicate. See also: Practical frame.

34.^Gemeente Zoetermeer (2019–2020).

35.^See, e.g., Drion (2022).

36.^“Cultureel Vermogen” (CV) is not easily translatable into English (just as “Cultural capability” is not adequately translatable into Dutch). “Vermogen” points to a combination of ability and opportunity, but it also has the connotation “potential power” as in the physics equation W = V x A (capability = difference x connectivity). The phrase “in and of society” indicates that the societal and individual aspects of CV are at the same time distinguishable ánd intertwined.)

37.^As such, it may provide a way to explore the specific ‘operational gap’ in the capabilities approach. (Gross & Wilson, 2020).

References

1

Ahmed S. (2012). On being included. London: Duke University Press.

2

Appignanesi L. (2018). Blurred binary code for the sustainable development of functional systems. Available at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/327137694.

3

Baecker D. (2013). Beobachter unter sich. Berlin: Suhrkamp.

4

Baecker D. (1993). Kalkül der Form. Frankfurt: Suhrkamp.

5

Baecker D. (2012). Wuzu kultur?Berlin: Kadmos.

6

Baraldi C. (2021). Unlocking Luhmann – a keyword introduction to systems theory. Bielefeld, Germany: Bielefeld University Press.

7

Baricco A. (2020). The game: A digital turning point. San Francisco: McSweeney’s Publishing.

8

Bateson G. (2002). Mind and nature: A necessary unity. New York, NY: Hampton Press.

9

Bateson G. (2000). Steps towards an ecology of mind. The University of Chicago Press.

10

Bauman Z. (1999). Culture as praxis. London: SAGE.

11

Bauman Z. (2011). Culture in a liquid modern world. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

12

Bausch K. C. (2001). The emerging consensus in social systems theory. New York: Kluwer.

13

Belfiore E. Bennet O. (2008). The social impact of the arts. London, United Kingdom: Palgrave MacMillan.

14

Belfiore E. (2014). ‘Impact’, ‘value’ and ‘bad economics’ - making sense of the problem of value in the arts and humanities. London, United Kingdom: Sage Publications. (In Press).

15

Bhabha H. K. (1994). The location of culture. London: Routledge.

16

Blom T. (1997). Complexiteit en contingentie. Kampen, Netherlands: Kok agora.

17

Bourdieu P. (1984). Distinction. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Harvard University Press.

18

Bourdieu P. Passeron J. (1990). Reproduction in education. London, United Kingdom: Society and Culture SAGE.

19

Braidotti R. (2005). Affirming the affirmative: On nomadic affectivity. Rhizomes11/12.

20

Burkart G. Runkel G. (2004). Luhmann und die Kulturtheorie. Frankfurt, Germany: Suhrkamp.

21

Caillois R. (2001). Man, play and games. Champaign, IL: University of Illinois Press.

22

Carbaugh D. (2012). A communication theory of culture. Available at: https://works.bepress.com/donal_ carbaugh/28/.

23

Ciompi L. (2004). Ein blinder fleck bei Niklas Luhmann?Soz. Syst.10, 21–49. 10.1515/sosys-2004-0103

24

Ciompi L. Endert E. (2011). Gefühle machen geschichte. Gottingen, Germany: Vandenhoeck and Ruprecht.

25

Damasio A. (2018). The strange order of things: Life, feeling and the making of cultures. New York, NY: Vintage Books.

26

Deacon T. W. (1998). The symbolic species. New York, NY: Norton.

27

Debruyne P. Gielen P. (2011). Community arts: The politics of trespassing. Amsterdam, Netherlands: Valiz.

28

Dissanayake E. (1974). A hypothesis of the evolution of art from play. Leonardo7 (3), 211–217. 10.2307/1572893

29

Dissanayake E. (2012). Art and intimacy: How the arts began. Washington, DC: University of Washington Press.

30

Donald M. (1991). Origins of the modern mind: Three stages in the evolution of culture. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Harvard University Press.

31

Drion G. (2018). Cultureel Vermogen: Nieuwe woorden voor het belang van cultuureducatie en -participatie in Nederland. Utrecht, Netherlands: LKCA.

32

Drion G. (2013). De waarden van sociaal-liberaal cultuurbeleid. Utrecht, Netherlands: Boekman 95.

33

Drion G. (2022). Het Leer-ecosysteem als speelveld. Utrecht, Netherlands: LKCA.

34

Drion G. (2023). The dynamics of culture. (Forthcoming in volume). London, United Kingdom: Routledge.

35

Eagleton T. (2000). The idea of culture. Malden, MA: Blackwell Manifestos.

36

Eco U. (1978). A theory of semiotics. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press.

37

Eco U. (1988). De structuur van de slechte smaak. Alkmaar, Netherlands: Bert Bakker.

38

Eu (2021). Porto santo charter. Available at: https://portosantocharter.eu/the-charter/.

39

Fischer-Lichte E. (2009). Culture as performance. Mod. Austrian Lit.42 (3), 1–10.

40

Fischer-Lichte E. (2008). The transformative power of performance. New York, NY: Routledge.

41

Gadamer H. (1993). De actualiteit van het schone: Kunst als spel, symbool en feest. Amsterdam, Netherlands: Boom.

42

Geertz C. (1973). The interpretation of cultures. New York, NY: Basic Books.

43

Gielen P. Elkhuizen S. Van den Hoogen Q. Lijster T. Otte H. (2014). De waarde van cultuur. Brussel, Belgium: Fred Dhont.

44

Gross J. Wilson N. (2020). Cultural democracy: An ecological and capabilities approach. Int. J. Cult. Policy26 (3), 328–343. 10.1080/10286632.2018.1538363

45

Hadley S. (2021). Audience development and cultural policy. London, United Kingdom: Palgrave MacMillan.

46

Hadley S. Belfiore E. (2018). Cultural democracy and cultural policy. Cult. Trends27 (3), 218–223. 10.1080/09548963.2018.1474009

47

Henricks T. S. (2015). Play and the human condition. Chicago, IL: University of Illinois Press.

48

Hoffmeyer J. (2008). Biosemiotics. Chicago, IL: University of Scranton Press.

49

Holden J. (2006). Cultural value and the crisis of legitimacy. London, United Kingdom: Demos.

50

Holden J. (2015). The ecology of culture. London, United Kingdom: Arts & Humanities Research Council.

51

Huizinga J. (1938). Homo Ludens. Groningen, Netherlands: Wolters-Noordhoff.

52

Ignatieff M. Roch S. (2018). Rethinking open society. Central European University Press.

53

Johnson M. (2007). The meaning of the body: Aesthetics of human understanding. University of Chicago Press.

54

Kagan S. (2011). Art and sustainability: Connecting patterns for a culture od complexity. Bielefeld, Germany: Transcript Verlag.

55

Keesing R. M. (1990). Theories of culture revisited. Canberra Anthropol.13 (2), 46–60. 10.1080/03149099009508482

56

Laermans R. (1999). Communicatie zonder mensen. Amsterdam, Netherlands: Boom.

57

Laermans R. (2002). Het cultureel regime. Amsterdam, Netherlands: Terra Lannoo.

58

Laermans R. (1997). Sociale systemen bestaan. Leuven, Belgium: Acco Uitgeverij België.

59

Laermans R. (2007). Theorizing culture or reading Luhmann against Luhmann. Cybern. Hum. Knowing14 (2-3), 67–83.

60

Lotman J. (2011). The place of art among other modelling systems. Sign Syst. Stud.39 (2/4), 249–270. 10.12697/sss.2011.39.2-4.10

61

Luhmann N. (2013). in Introduction to systems theory. Editor BaeckerD. (Cambridge, United Kingdom: Polity Press).

62

Luhmann N. (2000). Art as a social system. Stanford University Press.

63

Luhmann N. (1987). The medium of art. Amsterdam, Netherlands: Thesis Eleven, 18/19 101-113.

64

Luhmann N. (1997). Theory of society. Stanford University Press.

65

Machado I. (2011). Lotman’s scientific investigatory boldness: The semiosphere as a critical theory of communication in culture. Sign Syst. Stud.39 (1), 81–104. 10.12697/sss.2011.39.1.03

66

Maturana R. Varela J. (1984). The tree of knowledge: The biological roots of human understanding. Boston, MA: Shambala.

67

McConachie B. (2015). Evolution, cognition, and performance. Cambridge University Press.

68

Mitcpthell R. W. (1991). Bateson’s concept of metacommunication in play. New Ideas Psychol.9 (1), 73–87. 10.1016/0732-118x(91)90042-k

69

Moeller H-G. (2006). Luhmann explained. Chicago, IL: Open Court.

70

Moeller H-G. (2011). The radical Luhmann. Columbia University Press.

71

Nussbaum M. (2013). Creating capabilities. Harvard University Press.

72

Otte H. (2015). Binden of overbruggen – over de relatie tussen kunst, cultuurbeleid en sociale cohesie (Proefschrift). Groningen, Netherlands: Rijksuniversiteit.

73

Peirce C. H. (1986). Writings of charles S. Peirce: A chronological edition. Editors FischM. H.KloeseiC. J. W.RobertsD. D.ZieglerL. A. (Bloomington, IL: Indiana University Press). Vol. 3, 1872–1878.

74

Rampley M. (2009). Art as a social system – the sociological aesthetics of Niklas Luhmann. Available at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/299101474.

75

Ranciere J. (2010). Dissensus: On politics and aesthetics. London, United Kingdom: Bloomsbury.

76

Ranciere J. (2000). Het esthetische denken. Amsterdam, Netherlands: Valiz.

77

Roth S. Schütz A. (2015). Ten systems: Toward a canon of function systems. Cybern. Hum. Knowing22 (4), 11–31.

78

Schechner R. Schuman M. (1976). Ritual, play, and performance: Readings in the social sciences/theatre. New York, NY: Seabury Press.

79

Soja E. W. (1996). Thirdspace. Oxford, United Kingdom: Blackwell.

80

Spencer-Brown G. (1969). Laws of form. New York, NY: Dutton Press.

81

Stevenson D. (2016). Understanding the Problem of Cultural Non-Participation: Discursive structures, articulatory practice and cultural domination. PhD Thesis. Edinburgh (Scotland): Queen Margaret University.

82

Sutton-Smith B. (1997). The ambiguity of play. Harvard University Press.

83

Tarasti E. (2015). Sein und Schein: Explorations in Existential Semiotics. Berlin, Germany: De Gruyter Mouton.

84

Thibault M. (2016). The Meaning of play – playfulness as a semiotic device. Available at: https://www.academia.edu/23174518/The_meaning_of_Play_playfulness_as_a_semiotic_device.

85

Tomasello M. (2000). The cultural origins of human communication. Harvard University Press.

86

Turner V. (1982). From ritual to theatre – the human seriousness of play. New York, NY: PAJ Publications.

87

Uclg (2020). The 2020 Rome Charter. Available at: https://www.2020romecharter.org.

88

Unesco (2022). Reshaping policies for creativity. Available at: https://en.unesco.org/creativity/publications/2022-global-report-reshaping-policies-creativity.

89

Upton B. (2021). The aesthetic of play. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Mit Press.

90

Van Heusden B. (2010). Cultuur in de Spiegel. Groningen, Netherlands: RUG.

91

Van Heusden B. (2009). Semiotic cognition and the logic of culture. Pragmat. Cogn.17 (3), 611–627.

92

Van Maanen H. (2005). How to study art worlds: On the social functioning of aesthetic values. Amsterdam, Netherlands: University Press.

93

Vilc S. (2017). Kunst. Politik. Wirksamheit. Berlin, Germany: Humbolt Universität Berlin.

94

Volont L. Lijster T. Gielen P. (Editors) (2022). The rise of the common cityBrussels, Belgium: ASP.

95

Vygotsky L. (1996). in Cultuur en ontwikkeling. Editor Van der veerR. (Amsterdam, Netherlands: Boom).

96

Wheeler W. (2015). Biosemiotics and culture – An introduction. Green Lett.19 (3), 215–226.

97

Wilson N. Gross J. (2018). Caring for cultural freedom. London, United Kingdom: A.N.D., King’s College.

98

Wilson N. (2017). Towards cultural democracy. London, United Kingdom: King’s college.

99

Winnicott D. W. (1971). Playing and reality. London, United Kingdom: Routledge.

100

Zerubavel E. (2018). Taken for Granted – the remarkable power of the unremarkable. Princeton University Press.

Summary

Keywords

cultural communication, cultural policy, cultural democracy, cultural capability, systems theory

Citation

Drion GJ (2022) Towards a theory and practice of cultural communication. Eur. J. Cult. Manag. Polic. 12:11085. doi: 10.3389/ejcmp.2022.11085

Received

15 May 2022

Accepted

01 December 2022

Published

30 December 2022

Volume

12 - 2022

Updates

Copyright

© 2022 Drion.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Geert J. Drion, drion@ziggo.nl

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.