Abstract

Historically, theatre and dance have had challenging relationships with disability to say the least. This challenge stems from ableist perspectives that fail to consider specific needs and experiences of persons with disabilities. At all levels, from youth education to training and professional performance, opportunities are limited. Often, performing arts engagement is limited to audience seats for individuals with disabilities, more frequently this focus is on relaxed performances geared toward those identified as autistic. As the prevalence of autism diagnoses have increased, theatre and dance course engagement, specifically youth engagement, which is shown to have life-long positive impacts and predict regular and contined arts engagement, must be determined. Through an observational study, emphasizing autism research and theatre and dance classroom practices, student engagement was measured against curriculum and course planning. Through this strengthened understanding of engagement, theatre and dance curriculum can be planned to engage students on the spectrum. In building an equitable foundation for engagement, autistic students will be better equipped and prepared to move beyond audience seats.

Introduction

A 2016 autism prevalence report by the Autism and Developmental Disabilities Monitoring Network, issued by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention concluded that autism prevalence in the United States has more than doubled from the network’s first estimate in 2000 of one in 150 to one in 54 (Maenner, 2020: 2). Autism-Europe notes the prevalence between one and one and a half percent across 38 European countries (Barthélémy, 2019: 3–8). Autism-Europe and United States counterparts argue this prevalence of diagnoses must be met with increasing awareness and expansion of programs and services to support autistic individuals and their families (2019; Autism Society, 2020). This spotlight extends to many nations that have begun to address how they might be more inclusive for populations diagnosed with autism.

Over the past decade and a half, theatre makers have primarily focused on audience as the access point for students on the spectrum to engage with arts. My own experience in schools and theatres, creating autism-friendly performances—namely those with deliberate adjustments for sensory sensitivities—has led me to consider how we, as theatre practitioners, might be more effective at engagement beyond audience seats.

In my professional practice, I regularly encounter a youth-centred approach employed by community engagement leaders from arts, education, and government agencies. As early engagement predicts life-long participation and has been proven as an effective tool for educational outcomes, it is then paramount to consider whether special populations are being engaged in arts practice. Research supports a youth-centred approach; First conducted in 1982 and then on a quinquennial basis, the National Endowment for the Arts (2019) conducts a Survey for Public Participation in the Arts which consistently shows that supporting arts engagement in childhood directly informs participation as an adult (2019). Also in 1982, Paul DiMaggio (1982) published a positive correlation between arts engagement and grades, in so much as suggesting that “the impact of cultural capital will be greater on the grades of less advantaged youth, for whom the acquisition and display of prestigious cultural resources may be a vital part of upward mobility” (195). In a more recent 2019 report, Bowen and Kisida (2019), confirm through empirical analysis that arts are shown to positively impact student’s learning and reducing arts activities by embracing subject-only assessment-focused measures “pose significant costs” (17). For communities looking to benefit autistic youth through educational and social opportunities, arts pose a significant opportunity for individual and academic growth. However, for these benefits to take place it must be clear that students on the spectrum are being engaged.

Through an emerging partnership between the Burkhart Center for Autism Education and Research (Burkhart Center), the School of Theatre and Dance (SoT&D) at Texas Tech University (Texas Tech) theatre and dance courses were offered to the community. The partnership is supported by and managed through two SoT&D community arts courses, which take on the challenge of developing theatre and dance courses in consideration of underserved populations. In these courses, graduate students in theatre lead undergraduate mentees in theatre or dance. Activities are planned as either theatre or dance based on the undergraduate mentees. Faculty in theatre and dance oversee both courses and provide expert guidance in community arts practice.

Following an initial pilot study and in response to needs and adjustments to the pilot protocols, I developed the observational study in this article with consultation from Dr. Wesley Dotson, then Director of the Burkhart Center. In this case, we decided that the evaluation of theatre and dance curricula could be more effectively pursued by including additional effective engagement strategies and measures suited for students on the spectrum. Curriculum design in this case refers to the planned sequence of instruction for theatre and dance classes held at the Burkhart Center. Students in Burkhart Center theatre courses were divided into youth (5–10 years old) and teen (13–18 years old). The measurement rubric also allows for autonomous disciplinary course planning within a curriculum evaluation method designed to measure student engagement.

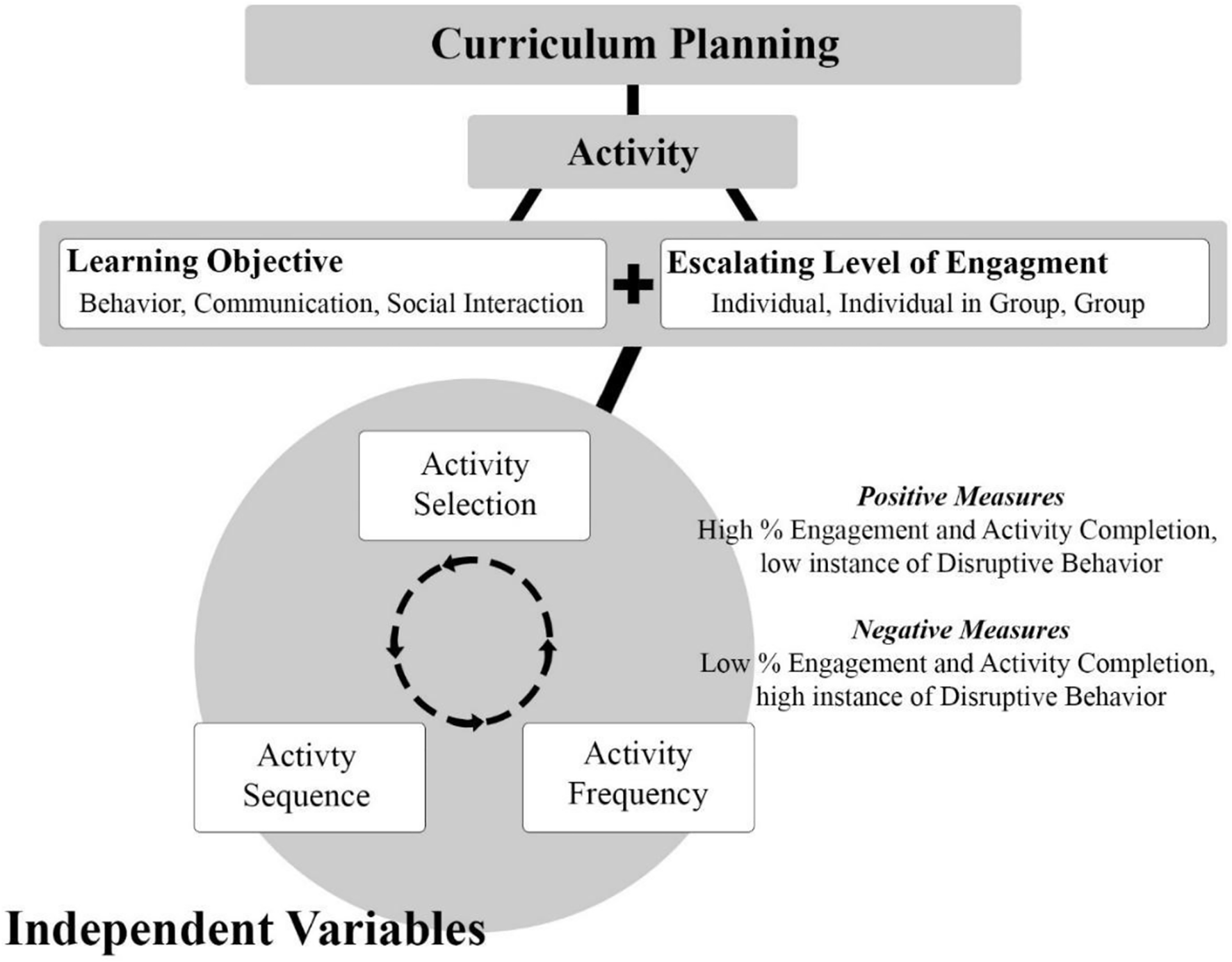

We considered that a positive outcome of student engagement is possibly connected to patterns in activity selection, sequencing, and frequency. Specifically, the way the course curriculum is designed might provide valuable insights when plotted against learning objectives, student participation level, and behaviour measures. Figure 1 details the relationship between variables observed and recorded in this study with further explanation in the following section.

FIGURE 1

Independent variable relationship—curriculum planning relates to learning objectives and increasingly complex engagement for activity selection, sequencing, and frequency with outcomes for positive and negative dependent variable measures. Source: Figure by author.

In this article, I advance preliminary answers to a number of questions regarding the development of effective engagement measures and strategies for students on the spectrum in theatre and dance classrooms. These questions include the following:

(1) Can borrowing measures of specific praise, disruptive behaviour, engagement, and activity completion from autism studies provide effective evaluation for theatre and dance curricula? What further insights can autism measures provide for activity selection, frequency, and sequencing?

(2) How does increasingly complex engagement (individual, individual in group, and group) affect total engagement for students on the spectrum? Is student engagement affected when instructors require group cooperation to complete an activity?

(3) Are learning objectives of behaviour (physical expression and/or interaction), communication (use of oral/verbal cues and interaction), and/or social interaction (interaction with others, including the instructor) able to predict levels of engagement? Does the sequencing or pairing of these objectives affect engagement?

(4) Does age group affect the outcome for students?

By seeking answers to these questions, I might support others working in community engagement from arts, education, and government agencies seeking youth-centred approaches to theatre and dance education for autistic students.

Background

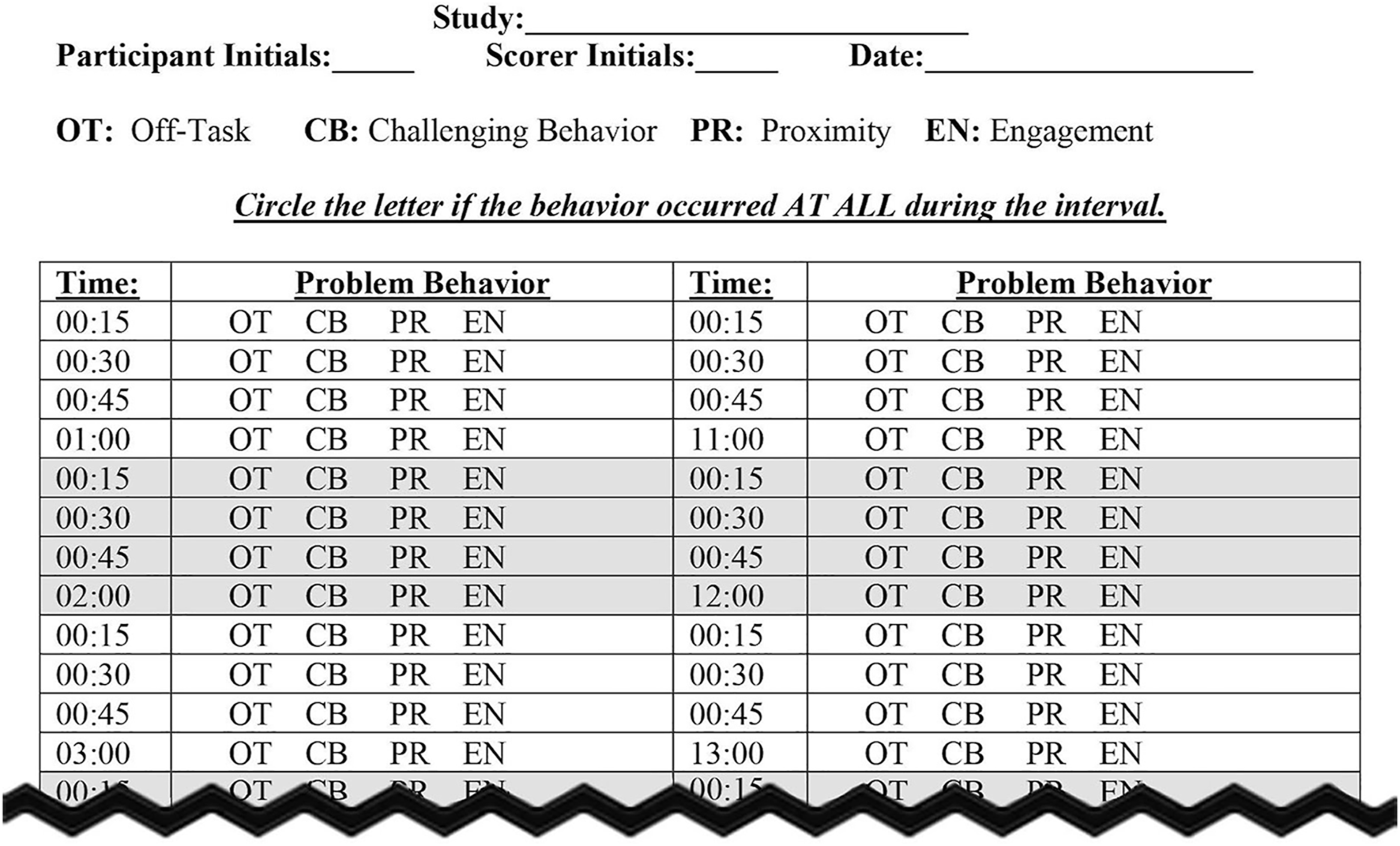

A pilot study provided preliminary assessment of evaluation methods used in autism research that were new to processes in theatre and dance classrooms. The pilot study that occurred in the spring of 2016 focused on theatre curriculum rather than intervention and used time-interval assessment. Figure 2 provides detail on the pilot study measurement sheet, while Figure 3 contains the measurements undertaken in the longer observational study. Following these figures, I discuss selection of measurement criteria and the reasoning behind selection of variables.

FIGURE 2

Session engagement interval scoring data sheet utilized by the Burkhart Center for autism education and research and for the theatre and dance pilot study. Source: Figure by author based on pilot study observation sheet.

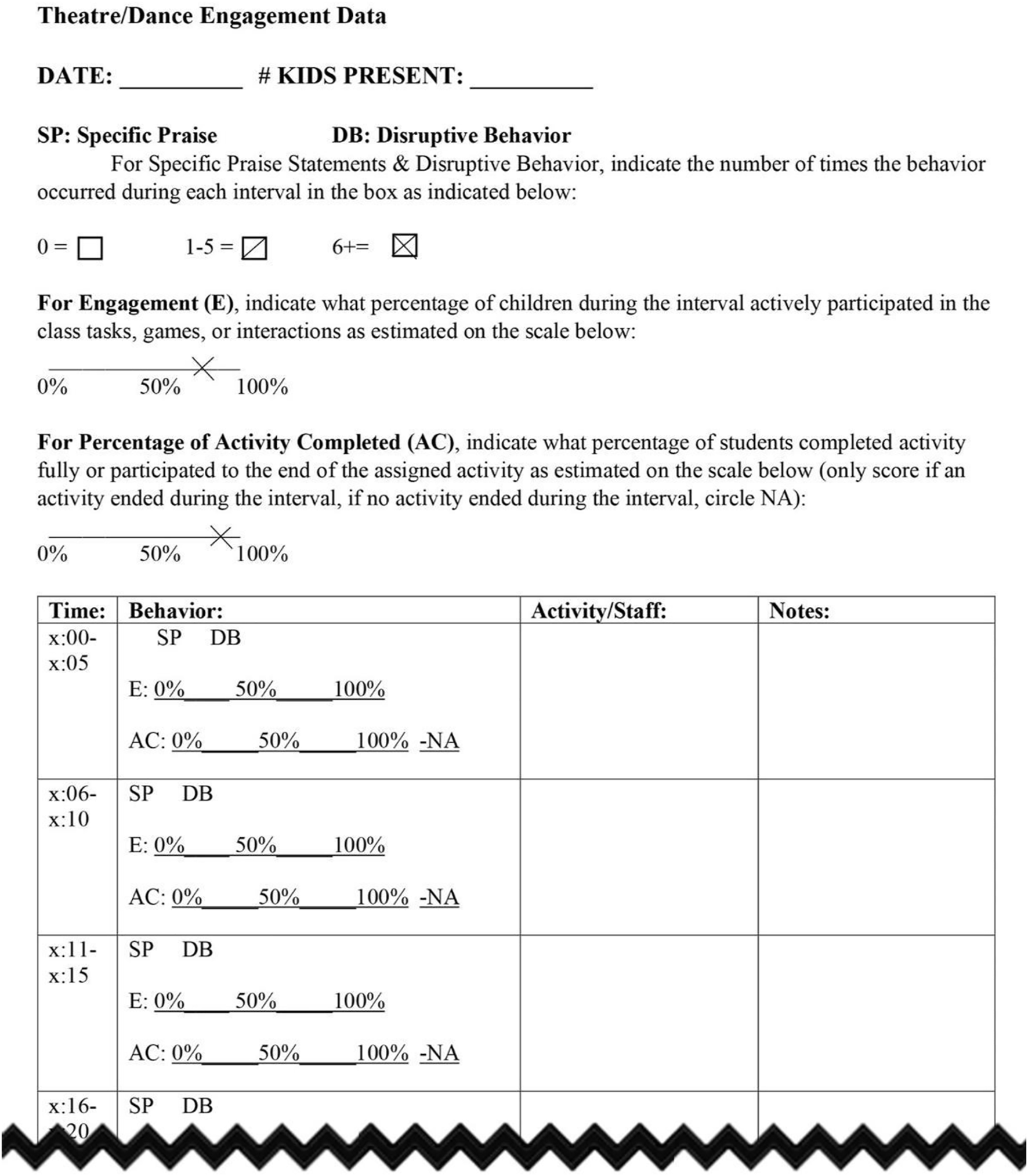

FIGURE 3

Theatre/dance engagement data sheet used for the observational study for theatre and dance courses taught at the Burkhart Center, administered by SoT&D graduate and undergraduate students in community engagement courses. Source: Figure by author.

The focus in this study was on theatre and dance instruction and not intervention. Intervention is defined as a one-on-one therapeutic method used to reduce and/or manage the physical and psychological symptoms of autism. An intervention might include special training to improve attention span or help manage anxiety in stressful social environments. Nevertheless, curriculum design in this case still requires a basic understanding of autism diagnosis. The American Psychiatric Association (APA) publishes a manual to identify and define conditions and disorders, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual-Fifth Edition (DSM-5), specifically outlines “persistent deficits in social communication and social interaction across multiple contexts” as one of the possible diagnosis criteria used by clinical psychologists and trained physicians (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). Autism symptoms can manifest in a spectrum of severity, some unnoticeable and relatively mild (such as a sensitivity to particular smells) to more extreme and severe (such as self-flagellation triggered by a strong smell).

Symptom domains, provide engagement insight and support evaluation criteria for curriculum design in theatre and dance: 1) social interaction impairments: “poor eye-contact, poor non-verbal communication, lack of mutual attention behaviours, poor awareness of others’ emotions, and poor peer relationships,” here non-verbal refers to non-speaking; 2) communication and play impairments: “poorly developed language, lack of conversational skill, language that is stereotyped, and play that is similarly stereotyped or lacks the quality of make-believe”; 3) repetitive and restrictive behaviours: “narrow interests, inflexible adherence to routines or rituals, repetitive motor movements, or preoccupations with parts of objects” (Fein, 1996: 23–35). Using these symptom domains from autism research, learning objectives of behaviour, communication, and social interaction were developed. In theatre and dance, behaviour is readily identified in activities, such as students performing a dance move or technique or students miming an action, like walking on a tight rope. As for communication, theatre is often more readily identified through speech. However, spoken and unspoken communication is essential in theatre activities and is readily understood in dance as a form or through a style. Social interaction is readily understood in both disciplines, theatre through production work and dance through group or partner choreography.

Beyond these learning objectives, scaling activity engagement also follows a pattern often taken in acting or dance classes, wherein students learn individual skills to develop better arts practice like monologues or technique independent of other participants, individual; students then progress to activities that may include others, like setting a stage environment or learning choreography with others, individuals in a group, and finally a production or recital (or what we termed group), a mix of social interactions or choreography that must be completed together for a performance to be complete. This describes increasingly complex engagement, which was also examined in relation to engagement in this study.

This study also utilized a method of time-interval assessment. In “Behavior, Social, and Emotional Assessment of Children and Adolescents,” Whitcomb and Merrell (2013) describe “essential characteristics of interval recording,” which involves: “1) selecting a time period for the length of the observation; 2) dividing the observational period into a number of equal intervals; and 3) recording whether the specified target behaviors occur during each interval” (2013: 103). They identify interval evaluation as a means to observe behaviour as the key tool for accurate assessment for individuals with autism; “it holds a prominent position as being one of the most empirically sound of these assessment techniques” (2013: 95). For accurate behavioural observation using intervals, Rebecca Sharp, Oliver Mudford, and Douglas Elliffe also advise recording a high volume of all interactions for proper sampling, no less than 10-min intervals observing at least 30% of total activity engagement to gain accurate representation data (2015: 153–159). In an initial study, “A Measure of Representativeness of a Sample for Inferential Purposes,” by Savlatore Bertino (2020) and supported in a later Sharp et al. (2015) study, they determined that observed behaviour and assumptions made about subsequent behaviour should rely on observational methods that “produce data that closely reflect the overall (i.e., true) occurrence of an individual’s behavior” (2006: 150; 2015: 153). Whitcomb and Merrell (2013) argue that, as long as observation includes “formal behavioral recording in naturalistic settings, or whether it is done informally as part of other measurement strategies” and “naturalistic observation,” then “behavioral observation” is the ideal “most direct and objective assessment” (2013: 95–97). They also further stipulate that to account for accuracy, researchers should “limit behaviors captured” that directly “relate to the overall time a specific behavior may take to accomplish,” a refinement also discovered in the pilot study when taking into count theatre and dance classroom engagement behaviours (2013: 103).

Engagement and activity completion are the primary behaviours tracked in interval observations. Logan et al. (1997) propose that engaged behaviour is “a [comprehensive] proxy for direct measures of learning” and accurately observe engagement “over multiple activities, instructional arrangements, and teach behaviors” (1997: 482). Corsello (2005) and Kishida and Kemp (2006) identify students on the spectrum as less engaged overall, exhibiting passive participation (2005: 82; 2006: 106–111). Mark Wolery, Donald B. Bailey and R. A. McWilliam identify positive measures of attentional engagement, behaviourally appropriate and on-task, as a “mediating influence on engagement,” to which McWilliam and Bailey (1995) consider active engagement an excellent measure of learning for students on the spectrum (Bailey and Wolery, 1992: 240–241; McWilliam and Bailey, 1995, 1995: 123–125). Deb Keen indicates that low levels of engagement further limit the practice of social skills, and that time-interval observations of engagement can assess activity schedules, autonomy, and instructional strategies in a way that can help mitigate issues of measuring engagement (2009: 3–5). Watanabe and Sturmey (2003) performed a study on engagement that discovered higher participation levels for students who were given autonomy to decide whether to engage and complete an activity (2003). Students have complete autonomy in the theatre and dance classroom at the Burkhart Center, which indicates active participation over timed intervals as a good measure for engagement.

Additional concepts included in my observational study that were borrowed from autism studies include those of disruptive behaviour and specific praise. Positive Behavior Supports and Interventions World define common disruptive behaviours as those tactics that are likely to disrupt a class (2019). Disruptive behaviours include physical distractions, voiced distractions, and social distractions (PBIS World, 2019a). In the PBS LearningMedia (2019) video series focused on “Managing and De-escalating Challenging Student Behaviors,” off-task disruptive behaviour is readily addressed by educators through refocusing and re-engaging the student in the activity (PBIS World, 2019b). This practice of re-engaging was also seen as effective in the pilot study, which reinforced behavioural measures for disruptive behaviours and introduced specific praise as a meaningful data point to collect.

The project

From spring 2017 to spring 2019, the observational study to assess student engagement and curriculum design took place at the Burkhart Center where theatre and dance courses are held. Graduate students and undergraduate mentees taught weekly courses observed by a trained observer and/or me.

Research design

We designed the observational study to measure engagement to discover effective curriculum strategies for students on the spectrum in theatre and dance courses. The study was meant to be unobtrusive; we recorded data behind a two-way mirror in two observation spaces and off to the side in the third space with no interaction with participants. Data collected and collection processes allowed for participants to remain anonymous, which was important considering the vulnerability of the target population of students on the spectrum.

To evaluate the effectiveness of theatre and dance curricula, the observational study included independent variables of activity selection, frequency, and sequencing with dependent variables of activity completion, engagement, disruptive behavior, and specific praise, with independent variable relationships identified in Figure 1. These variables allow for discovering relationships between student engagement and theatre and dance activities through percentage of students engaged and percentage of activity completed with activity details and notes recorded over 5-min intervals. Figure 3 provides a sample of the data collection sheet used in this study. Following collection of data, activities were coded into increasingly complex engagement and learning objectives to uncover effective strategies in curriculum planning. By measuring engagement through observation methods proven effective for individuals with autism, I can better evaluate theatre and dance curricula and potentially plan more effective engagement strategies for students on the spectrum.

For this study, we collected data each semester, from spring 2017 to spring 2019, for nine Burkhart Center courses. We required a minimum of 80% of days observed, with 100% of intervals observed on those days. Only two courses went unobserved because I was unable to assign a trained observer to cover the entire length of the course. Each course ran for 7 weeks in spring semesters or 8 weeks in fall semesters, six occurring twice a week (one fall, five spring) with 12 5-min intervals and three occurring once a week (one fall, two spring) with 18 5-min intervals, providing a total possible 1.428 intervals for measurement. The volume of intervals create higher reliability for behavior measures and improve reliability in coded levels of engagement and learning objectives. The volume and consistency of measures helps to ensure validity of the observational study.

Participants and setting

The Burkhart Center Administrative Business Assistant sent email advertising available dance and theatre courses to the guardians of potential participants. All participants had previously attended events or received services from the Burkhart Center. The youth courses were for elementary-age students, ranging from ages 5 to 10. The Burkhart Center advertised teen courses and allowed participation for ages 13 to 18.

Courses were offered in the afternoon twice a week for 1 h, or on Saturday for 90 min. Afternoon classes that met Monday/Wednesday or Tuesday/Thursday started at either 3:00 p.m. or 4:00 p.m. and were held in one of the three classrooms at the Burkhart Center. Saturday courses were for teens only and began at 10:00 a.m. The Burkhart Center limited enrollment at ten for any given course. SoT&D graduate and undergraduate to Burkhart Center student ratio was typically around one to two for classes with low enrollment, and one to three for fully enrolled courses.

Classes were held in three different spaces at the Burkhart Center. The first was Burkhart Center’s clinical space, a large open room with restrooms and a kitchen at one end, a mirrored wall at the other, and several windows looking to the exterior. The clinical space is roughly 1,000 sqft in size with the mirrored wall concealing an observation room. With approximately 400 sqft of open floor space, the second classroom is a modular space with tables and chairs removed from the room for activities on the other side of the mirrored observation room. The third room is the gymnasium at the Burkhart Center, with roughly the same usable floor space as the clinical space, though it has a footprint closer to 800 sqft. The gymnasium has no hidden room, so the observer or I sat off to the side on a chair when recording class data.

Measures

Using data collection sheets (Figure 1), observers measure engagement, activity completion, behavioural measures, and space for notation of class (youth or teen), date, time, activities, class size, number of instructors, and length of class.

Engagement, the primary dependent variable across the 5-min interval, measured active participation in theatre and dance activities. The percentage of engagement measured the overall percentage of students engaged in an activity. Active participation required students to follow the rules and expectations delineated by the instructor(s). For instance, an activity may have required students to move with sound in an environment (e.g., act by moving and making sounds like pig on a farm: student was on all fours, pretended to wallow in mud, and squealed/snorted like a pig). If one of five students sat quietly, even in the given play space, we recorded the total percentage engaged as four in five or 80%.

Activity completion, the secondary dependent variable measure for participation, was only recorded during intervals when an activity concluded. Observers selected a percentage of activity completion based on the ratio of students who finished an activity to the total number of students. Observers recorded participants engaged for appropriate intervals and only recorded activity completion when students accomplished all activity tasks given by the instructor.

Behavioural measures for disruptive behaviour and specific praise are dependent variables compared against engagement. Disruptive behaviour included any off-task actions that inhibited activity completion by one or more members of the group including themselves, other students, instructors, or mentees. Specific praise measured the number of instances when an instructor or mentee responded positively to student actions.

The data collection also noted activity selection. While not a behaviour measure, attention to this activity allowed for the evaluation of engagement, and important measure given increasingly complex engagement and learning objectives based on independent variables of activity selection, sequencing, and frequency.

Procedures

All observers were required to fulfill Human Subject Training requirements for Texas Tech, to have had experience in theatre and dance and to have previously worked with students on the spectrum. Training included the use of data sheets (Theatre/Dance Engagement Data Sheet and Theatre/Dance Engagement Digital Data Sheet). Each measurement rubric was explained in detail, with examples provided, and with an opportunity for questions following. Observers viewed class sessions and completed course data observation intervals, with support from Dr. Dotson and me during at least their two initial observations, this allowed for real-time training of observation protocols.

The assigned observer recorded the date in MM/DD/YYYY format, as well as the number of students in attendance, with tardy arrivals noted in the interval in which they occurred. They then noted the start time in the first interval. They recorded the number of instructors.

Over each interval, the observer noted behavior and activity details. For instances of specific praise or disruptive behavior, observers tracked across intervals and then selected no praise/disruptive behavior, one to five instances, or six or more instances. The observer completed the “Activity/Staff” section to include the activity being performed, the identity of the instructor lead, and the rules and procedures for the new activity. Observers did not record student names but noted if an activity was student led.

At the end of the interval, the observer marked the estimated participation percentage and activity completion percentage for students. Percentage selection is directly related to the number of students engaged in an activity and a separate measure for activity completion, both compared to total number of students. If no activity was concluded by the end of the interval, no percentage was recorded. If two activities occurred in the same interval, the observer noted activity completion for all activities finished in the interval. The interval observations repeated until the end of the class session.

Following observations, I coded activities into level of increasingly complex engagement and learning objectives. The coding of increasingly complex engagement uses three levels of participation: individual, individual in a group, and group. Activities were only assigned one level of engagement, based on requirements to engage and complete an activity. Activities were also coded for learning objectives of behavior (physical expression and/or interaction), communication (use of oral/verbal cues and interaction), and/or social interaction (interaction with others, including the instructor). Up to two learning objectives were coded for each activity; based on instruction and desired output, a primary learning objective was identified.

Results

Curriculum design was distinctive for each course even though all courses shared a similar disciplinary origin. Only one notable difference arose from the fact that a written guide was completed in December of 2017, and so was only available to instructors in subsequent semesters. The total available classes to observe was 108 (1.334 intervals).1 In the study, we observed 89 class sessions and 1.080 intervals for a total of 90 h of instruction, with details provided for comparison in Table 1. I evaluated the success of curriculum for each class by using measures of engagement, activity completion, disruptive behaviour, and specific praise. Once these scores were compiled, I examined activities for patterns of increasingly complex engagement and learning objectives to uncover any significance in activity selection, sequence, and frequency.

TABLE 1

| Classes | Intervals | |

|---|---|---|

| Totala | 108 | 1,334 |

| 80% Threshold | 86 | 1,067 |

| Observed | 89 | 1,080 |

| Total Teena | 22 | 375 |

| Total Youtha | 86 | 946 |

| 80% Threshold Teena | 18 | 300 |

| 80% Threshold Youtha | 69 | 757 |

| Observed Teen | 19 | 335 |

| Observed Youth | 69 | 806 |

Observational study classes and intervals observed.

Calculated from actual possible classes and intervals to observe.

Source: Table by author.

My first research question asked if borrowing measures of specific praise, disruptive behaviour, engagement, and activity completion from autism study could provide effective evaluation for theatre and dance curricula, and what further insights might autism measures provide for activity selection, frequency, and sequencing. Each observed course followed a specific pattern, but no two courses followed identical patterns, which resulted in different participation outcomes for each class and variation across study measures.

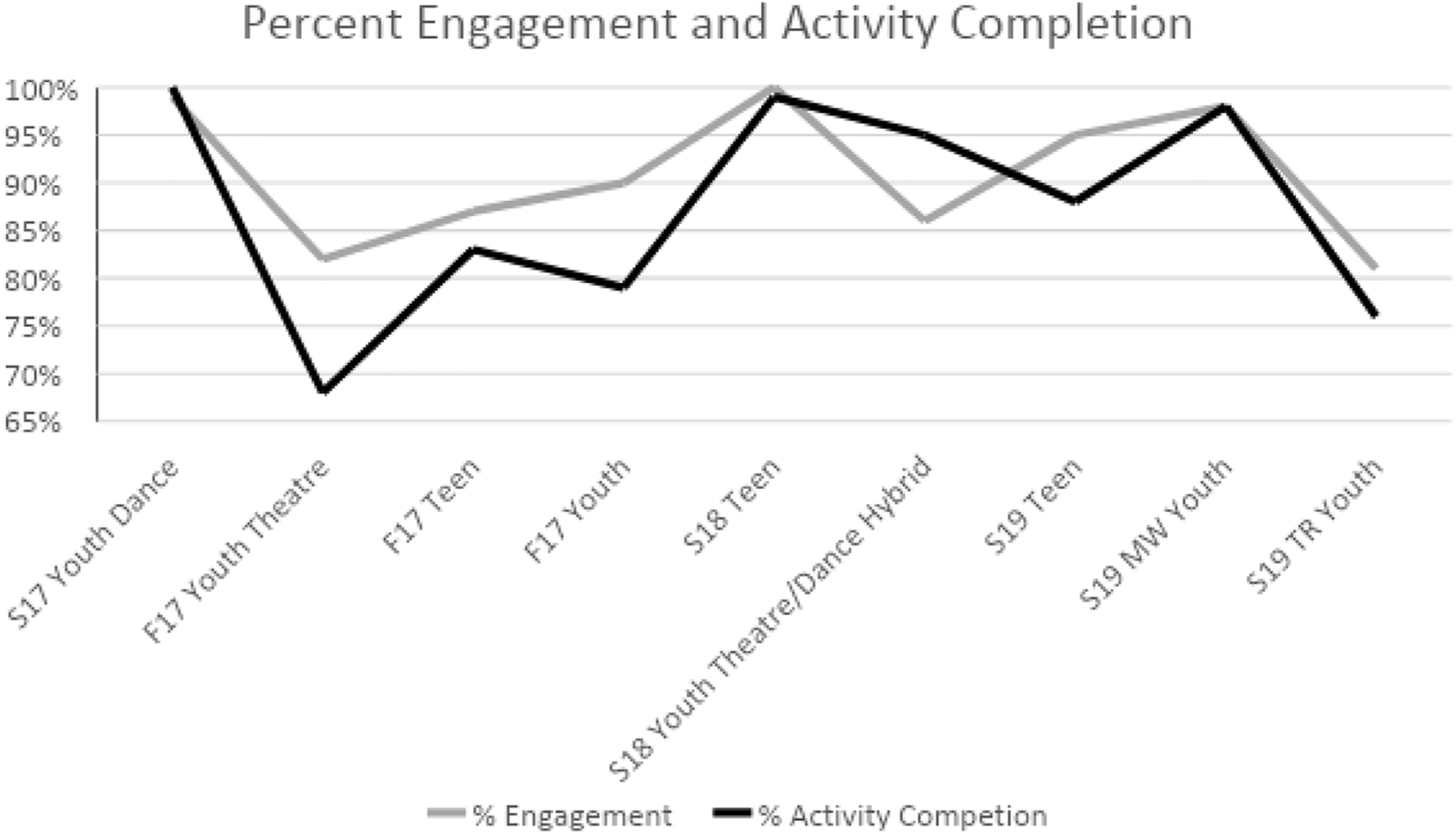

The engagement measure was taken across all intervals and measured the active engagement of students. Table 2 reveals average engagement and Table 3 activity completion. Figure 4 provides these measures together across all classes. The average percentage of engagement across all intervals in the study was 91%, with the average for each individual semester falling within two percentage points of the overall engagement average. This percentage was significantly higher than that recorded for the pilot study (68%) but is justified by consistent results across all classes. This suggests that the new measurement protocols were more effective at measuring engagement for theatre and dance courses and proves consistency in the engagement measure.

TABLE 2

| Average (%) engaged | |

|---|---|

| Spring 2017 | 91 |

| Youth Dance | 99 |

| Youth Theatre | 82 |

| Fall 2017 | 89 |

| Teen | 87 |

| Youth | 90 |

| Spring 2018 | 92 |

| Teen | 100 |

| Youth Theatre/Dance Hybrid | 86 |

| Spring 2019 | 91 |

| Teen | 95 |

| Monday and Wednesday Youth | 98 |

| Tuesday and Thursday Youth | 81 |

| All Courses | 91 |

Student engagement percentage.

Source: Table by author.

TABLE 3

| Average (%) activity completed | |

|---|---|

| Spring 2017 | 88 |

| Youth Dance | 100 |

| Youth Theatre | 68 |

| Fall 2017 | 81 |

| Teen | 83 |

| Youth | 79 |

| Spring 2018 | 97 |

| Teen | 99 |

| Youth Theatre/Dance Hybrid | 95 |

| Spring 2019 | 90 |

| Teen | 88 |

| Monday and Wednesday Youth | 98 |

| Tuesday and Thursday Youth | 76 |

| All Courses | 89 |

Activity completion percentage.

Source: Table by author.

FIGURE 4

Percent engagement and activity completion graph comparing participation and engagement measures for theatre and dance courses in the observational study. Source: Figure by author.

Activity completion, the other participation dependent variable, served as a secondary engagement measure. We observed activity completion in 55% of the 1.080 intervals, or 597. Of these intervals, students completed activities 89% of the time. Comparing the two participation measures against each other shows an expected positive relationship between engagement and activity completion. The two lowest rated were the lowest rated in activity completion. This trend was also true for highest participation percentages.

We recorded disruptive behaviour in 7% of intervals and specific praise in 16%. The concurrence of both was only, 65% for all intervals, with a 3% chance of overlap. Despite limited intervals containing both, observers noted improved engagement and activity completion rates, with instances of disruptive behaviour limited or eliminated in intervals following. Observers noted the continuation of disruptive behaviour in subsequent intervals when no instructor gave specific praise. This suggests that specific praise can mitigate disruptive behaviour, but as the concurrence was limited it is impossible to definitively say that specific praise will always mitigate disruptive behaviour. However, we observed specific praise more often in classes with higher engagement and activity completion percentages. When measured against each other, specific praise mitigated disruptive behaviour nearly 100% of the time.

The courses that proved the most successful in engaging students demonstrated consistent activity selection across class sessions and the course. Activity selection included a course-specific and consistent mix of increasingly complex engagement and learning objectives. Classes that performed average for engagement and activity completion also showed consistent selection, but more often relied heavily on a single level of engagement or learning objective and included a significant portion of variable activity selection. The courses with the lowest engagement levels relied predominantly on a single activity type, ones with the same level of engagement and learning objective or a variation with no discernible pattern. The result of unbalanced selection revealed reliably lower engagement across courses without consistent curriculum planning.

Courses with the highest engagement and activity completion levels reliably selected the same activity or the same activity type, frequency, with the same level of engagement and learning objective, from class to class and across the course. Courses performing average and below average for participation measures had too much variation, regular change in activity more frequently than the average 8 min, and/or too little variation in activity or activity type, with change occurring after around 20 min.

Activity sequencing per class session and across courses revealed engagement patterns again. As noted in the course breakdown, the most successful courses showed a pattern in class sessions of consistent or alternating learning objectives. Engagement and activity completion levels were greater when behaviour-centred activities opened class sessions. Inconsistent sequencing or broadly varied activity selection over the course and class sessions precipitated lower engagement levels. However, when a student-selected activity preceded, student engagement and activity completion remained high over the class.

Courses designed with consistent curriculum had better percentages of engagement and activity completion. These measures proved effective for evaluating theatre and dance curricula design as patterns emerged that were consistent for courses with higher, average, and lower levels of participation and directly correlated to consistent planning.

The next question addressed by the observational study was how increasingly complex engagement (individual, individual in group, and group) affected total engagement for students on the spectrum, and whether student engagement was affected when instructors required group cooperation in the completion of an activity.

I found student engagement and activity completion percentages to be higher for group activities. Given the interval instances for individual level of engagement and participation, 23% of individual activities recorded lower, below 100%, of engagement and/or activity completion. Similarly, individual in group scored 22% lower across intervals, but group activities were only 13% lower. Student engagement appears to be positively affected by group cooperation for theatre and dance activities. Disruptive behaviour occurred more often in individual or individual in group activities. Again, no positive correlation was found in changing level, but rather by instructors offering specific praise. The length of the course and the age group revealed no notable differences in engagement when considering increasingly complex engagement.

The third research question I addressed using data collected was whether learning objectives of behaviour (physical expression and/or interaction), communication (use of oral/spoken cues and interaction), and/or social (interaction with others, including the instructor) are able to predict levels of engagement, and whether the sequencing or pairing of these objectives affect engagement. I coded activities into learning objectives: 50% into communication, 45% in behaviour and nearly 5% in social interaction. Learning objectives alone are not likely to predict participation percentages. Reviewing activity selection, I noticed activities were most often coded with the following levels of engagement and learning objectives: individual/behaviour, individual/communication, individual in group/communication, group/behaviour, and group/communication. Among classes recording lower levels of engagement (23% of observed intervals), individual/behaviour and individual in group/communication made up the overwhelming majority, 60%. Overall, for popular combinations, communication comprised nearly 50% and behaviour 45%. These combinations are common and can be found in well performing courses, which suggests that these types of activities should not be avoided but instead considered within a well-planned curriculum. Within some of these intervals, observers recorded disruptive behaviour; 79% occurred in individual/behaviour (35%) or individual in group/communication (44%) activities. This suggests that instructors could offer more specific praise when incorporating individual/behaviour or individual in group/communication into curriculum planning.

I was unable to distinguish significant differences for my final research question regarding whether age group affected the outcome for students. Teens and youth had similar instances of disruptive behaviour and specific praise, and when considering activity selection, sequencing and frequency patterns against participation rates, there appears to be no variation in results for increasingly complex engagement or learning objectives with respect to student ages.

Conclusion

We undertook this observational study to further develop strategies to support engagement for students on the spectrum in theatre and dance classes. To assess theatre and dance curricula, we borrowed measures found in autism studies to measure engagement, identify learning objectives (behaviour, communication, and social interaction), and consider escalating levels of engagement (individual, individual in group, group). The measures selected revealed clear indications for curriculum planning for theatre and dance courses for students on the spectrum. Definitively, the measures selected provided significant and relevant measurements of participation, engagement, and activity completion. When combined with measures of disruptive behaviour and specific praise, participation was further interpreted and as noted, positively affected.

These measures alone only provide part of the curriculum planning picture. We were able to reveal the significance in activity selection, frequency, and sequence when examined across all measures. Specifically, curriculum planned with activity selection closely linked to sequence and frequency showed higher levels of participation. Courses with consistent activity selection, consideration for sequence in class sessions, and frequency of activity type demonstrated positively impacted participation, as seen in the highest performing courses. The lowest performing courses offered no consistency across activity selection, limited sequencing uniformity, and exhibited nearly no frequency of activity or activity type, except for student influenced selection. This suggested high impact of autonomy in activity engagement and completion. Average performing courses adhering to more consistent activity planning revealed common learning objectives, and with variation in level of increasingly complex engagement improved engagement or activity completion for students on the spectrum.

Observations also revealed common combinations occurring in activity learning objectives and increasingly complex engagement. Disruptive behaviour was predominantly (95%) found to occur during two of these combinations: individual/behaviour and individual in group/communication. Planning is not likely to eliminate disruptive behaviour, but instructors can be aware of activities that require increased specific praise. By uncovering patterns like these, curriculum preparation can better support activity planning in theatre and dance courses for students on the spectrum.

Using these measures, our observational study was able to reveal strategies to improve engagement for students on the spectrum in theatre and dance courses. Curriculum planning that uses consistent activity selection, sequencing, and frequency leads to better engagement, an assertion confirmed by my analysis of our observations. The results of this study additionally suggest that curriculum planning can be improved by considering learning objectives and increasingly complex engagement as they relate to activity selection, sequencing, and frequency.

Recommendations

If we were to undertake this study again, I would retain all measure features and activity coding. They provided clear, effective, and consistent results for student participation, engagement and activity completion while being readily recorded by observers. Observation of the courses offered strategies to improve engagement in theatre and dance classrooms with students on the spectrum. The most effective strategy revealed was consistency of curriculum selection. Since the instructors freely designed curriculum for these courses, future observational studies might select features to be individually isolated, in order to measure success for specific learning objectives and increasingly complex engagement combinations as they relate to activity selection, sequencing and frequency.

Based on my experience, autism research, and our observational study, my recommendations for curriculum planning theatre and dance courses with students on the spectrum are as follows:

• Instructors should identify a clear vision and focus for the course; Instructors should identify goals and learning objectives to inform activity selection, sequencing, and frequency. Consistency proved a key element in the most successful courses in this study.

• Age appropriateness is also an important feature when planning. Though students on the spectrum may have communication barriers, their IQ is not limited by autism. If instructors are insensitive to a student’s abilities or needs, they may create an environment where the student is less likely to trust the instructor. While we did not see variations in our age group measure, in considering our population without prejudice or bias, we are better able to get a clear picture on positive engagement.

• Specific praise should be incorporated regularly into classes and planned when an activity is especially challenging to students. This was shown to have a positive impact on courses with high participation and helped to mitigate issues in classes that had average and below average participation.

• If there is room for student selected activities or a selection between activities, students are anticipated to be more engaged. Autonomy is important and should be incorporated as possible into activity selection. Autonomy of activity selection was shown to be the greatest predictor of continue and sustained engagement, even in the courses with the lowest engagement.

This study was able to reveal positive correlations between measures and coded activities, which can provide a crucial first step in curriculum planning with students on the spectrum in mind. The lack of similar research makes this study crucial to exploring theatre and dance curricula design to improve engagement for students on the spectrum. The courses in this study only provided a short opportunity, with few weekly sessions, to review part-time curriculum. Ideally, a future study would include a full-length course, one fitting into school curriculum.

The study might also be adapted to review college and university age courses for theatre and dance or examine ways to explore autonomy in activities planned in other subject areas. I will continue to apply this unique approach as I explore ways to further engage students and artists on the spectrum. Though this process is an uncommon way to plan theatre and dance curricula, I suspect continued unsiloing of disciplinary practices can provide a basis for more robust examinations of theatre and dance processes, so that they can become more equitable to persons with disabilities.

This research project and similar have potential to impact policy and practice. As organizations seek to engage special populations and underserved communities, like those on the spectrum, programs can better organise. Additionally, through university programs, future practitioners are better able to address and plan for work as teaching artists or those seeking to engage various members of their community in practice. Artists and arts leaders will be able to better consider the target population, their needs and experiences, and measuring their engagement, based in relevant disciplinary measures. Community leaders, government organizations, and arts agencies are likely to set better institutional and education policies when special populations engagement is better understood. In doing this work and building capacity for access, we are better prepared to welcome diversity, build inclusive environments, and provide more equitable engagement.

Statements

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

The author confirms being the sole contributor of this work and has approved it for publication.

Acknowledgments

This study and results were made possible by support from Dr. Andrew Gibb, Dr. Wesley Dotson, Professor Rachel Hirshorn-Johnston, Dr. Paul N. Reinsch, and Dr. Virginia E. Whealton. Further acknowledgment to The Burkhart Center for Autism Education and Research for its commitment to the arts and Texas Tech University’s Theatre and Dance in the Community for its inclusive programming.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Footnotes

1.^Over the course of the study, we discovered that classes often began late or ended early, reducing observational intervals by at least one for each class session, resulting in an average of 11 instead of 12 intervals for youth classes and an average of 17 instead of 18 intervals for teen courses. An average of 53% of the classes had fewer than anticipated intervals to observe, with none exceeding, reducing intervals from 1.428 to 1.334. To meet the 80% minimum observations required, we needed to observe a total of 86 classes (1.067 intervals). Spring term presented low attendance or class cancelations during spring break periods, including during Texas Tech and students’ spring breaks on different weeks. Spring break for students only affected youth courses.

References

1

American Psychiatric Association (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 5th ed.

2

Autism Society (2020). What is Autism?Prevalence.

3

Bailey D. Wolery M. (1992). Teaching infants and preschoolers with disabilities. 2nd ed. New York: Merrill.

4

Barthélémy C. (2019). An autism-europe official document, people with autism spectrum disorder: Identification, understanding, intervention. 3rd ed. Autism-Europe, 40.

5

Bertino S. (2006). A measure of representativeness of a sample for inferential Purposes. Int. Stat. Rev.74 (2), 149–159. 10.1111/j.1751-5823.2006.tb00166.x

6

Bowen D. Kisida B. (2019). Research report for the houston independent school district, investigating causal effects of arts education experiences: Experimental evidence from houston’s arts access initiative. Houston7 (411), 28.

7

Corsello C. M. (2005). Early intervention in autism. Infants Young Child.18 (2), 74–85. 10.1097/00001163-200504000-00002

8

Di Maggio P. (1982). Cultural capital and school success: The impact of status culture participation on the grades of U.S. High school students. Am. Sociol. Rev.47 (2), 189–201. 10.2307/2094962

9

Fein D. (1996). “The nature of autism,” in Making a difference: Behavioral intervention for autism. Editors MauriceC.GreenG.FoxxR., 23–35.

10

Kishida Y. Kemp C. (2006). A measure of engagement for children with intellectual disabilities in early childhood settings: A preliminary study. J. Intellect. Dev. Disabil.31 (2), 101–114. 10.1080/13668250600710823

11

Logan K. R. Bakeman R. Keefe E. B. (1997). Effects of instructional variables on engaged behavior of students with disabilities in general education classrooms. Except. Child.63 (4), 481–497. 10.1177/001440299706300404

12

Maenner M. J. (2020). Autism and developmental disabilities monitoring network, prevalence of autism spectrum disorder among children aged 8 years, 11 sites, 27. United states, Atlanta: MMWR Surveillance Summary, 12. 2016.

13

McWilliam R. A. Bailey D. B. (1995). Effects of classroom social structure and disability on engagement. Top. Early Child. Special Educ.15 (2), 123–147. 10.1177/027112149501500201

14

National Endowment for the Arts (2019). U.S. Patterns of arts participation: A full report form the 2017 Survey of public participation in the arts. Washington D.C., 108.

15

PBIS World (2019a). Off-task behavior.

16

PBIS World (2019b). Off-task non-disruptive.

17

PBS LearningMedia, KET education, off-task behavior, 1 Aug. 2019.

18

Sharp R. A. Mudford O. C. Elliffe D. (2015). Representativeness of direct observations selected using a work-sampling equation. J. Appl. Behav. Analysis48 (1), 153–166. 10.1002/jaba.193

19

Watanabe M. Sturmey P. (2003). The effect of choice-making opportunities during activity schedules on task engagement of adults with autism. J. Autism Dev. Disord.33 (5), 535–538. 10.1023/a:1025835729718

20

Whitcomb S. Merrell K. (2013). Behavioral, social, and emotional assessment of children and Adolescents. 5th ed. New York: Routledge.

Summary

Keywords

theatre, dance, education, autism, engagement

Citation

Phong W (2022) Beyond the audience: Creating effective engagement strategies for students on the spectrum in the theatre classroom. Eur. J. Cult. Manag. Polic. 12:11086. doi: 10.3389/ejcmp.2022.11086

Received

15 May 2022

Accepted

01 December 2022

Published

15 December 2022

Volume

12 - 2022

Updates

Copyright

© 2022 Phong.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Winter Phong, winter.phong@uky.edu

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.