Abstract

The 2020 COVID pandemic has been a major challenge for Mexican creative workers, whose working conditions were already precarious since before the world crisis. Through qualitative analysis of conversational interviews, we identified a series of adjustments and professional decisions made in the context of social distancing. Our findings show that precarious working conditions in which they already worked were aggravated during the pandemic social distancing periods to even threaten their possibilities to keep their place in the creative sector. We identified five different earning strategies with which they navigated uncertainty during the pandemic. Finally, we discussed the inequalities they face while trying to earn an income through multiple activities and, at the same time, updating their knowledge and capabilities to adjust their creative work to the new realities.

Introduction

This paper analyses the living and working conditions of a group of people in the metropolitan area of Mexico City’s creative sector during the COVID-19 pandemic, a time in which live and public activities were forced to close following the social distancing measures imposed by the government to control the expansion of the virus. Based on previous data about the general state of the creative sector, our starting point is the assumption that their labour market has been historically characterized by informality, low incomes, lack of jobs, and precarity, but this is often perceived as a way of life instead of a problem.

This paper comes out of broader comparative research, funded and managed by the Australian Research Council, at the University of Technology Sydney, and Universidad Veracruzana for Mexico’s case study. We approached a group of people whose main work is defined within what has been broadly called creative work and locate themselves on the edge of what could be defined as middle class. Because of the creative sector’s fragility and the lack of stability on their socioeconomic statuses, these group of subjects have experienced a hard shock on their incomes and household budgets, but must importantly on the possibility of continuing to work on their creatives jobs as many of them have made a living out of performance or live arts that need public spaces and face-to-face interactions. They have had to adjust their working activities, their daily life habits, and how they foresee the coming future in these still uncertain times. With this in mind, we attempt to examine the specifics of the adjustments made to their jobs, what tools that they have had available for this transition, and what kind of strategies they have had in hand to navigate what is likely the most challenging period for the sector in many years.

This paper is structured in four sections. In the first one, we lay out the background for this research, which includes a brief description of Mexico City Metropolitan Area and some general data about its main features, an overview to the creative sector working conditions, and the current working conditions of our interviewees. In the second one, we acknowledge our theoretical and methodological approach which comes from our main project No Longer Poor, Not Yet Middle Class, New Consumer Cultures in the Global South. The third section offers an in-depth analysis of information we gathered in our fieldwork. To answer our main questions, we established the general characteristics of our interviewees, along with the professional activities they used to carry out before the social distancing mandate; as well as their current economic activities, how they pursued an income during 2020 and 2021 (during social distancing measures) and what sort of strategies and resources they have used to keep working/living under these circumstances.

To finalize, we discuss our findings, trying to articulate our qualitative approach to the narratives about their strategies to secure an income during the given period and to articulate an interpretative explanation on the transitions from pre-existing precarious living conditions to the impact of the pandemic crisis on their employment fragility, along with the coping strategies to make a living while their jobs were shut down, some of which we argue could lead to a rethinking of cultural policies concerning employment and working conditions for this workers.

Theoretical approaches

The labour within the artistic and cultural sector have got different definitions along the way depending different perspectives and context, as this has proved to be an evolving term. Florida (2002) gives a notion of creative class that gained importance as starting point to talk about cultural or creative industries, but we find disagreeable that creates an idea of development and integration of creative work to the neoliberalism economies as desirable. In the same line, in Mexico it is been debating the term Protected Industries by Copyright (Piedras, 2004), which claims creative work can be define as activities based on authorship and monetization of copyrights; although is creators rights, these are concepts that guide creative work towards quantity production and profit focus. UNESCO (2010) also offer a broad definition and refers individuals and not to the institutions, as the ones who participate actively of an economic sector, without necessarily being part of a large consortium or at least not being employed in a permanent basis. This is a closer notion to what we observed in a field characterized by no full-time jobs or institutional structure.

We refer to creative work since it is a type of work that exist in a capitalist economic model (Comunian and England, 2020) that has allowed the development of an increasingly inequitable and unfair labour market that offers poor alternatives for creative workers with no social and cultural capital. Our sample of individuals who agreed to take part on our research project define themselves as part of a broader creative sector definition which includes arts and creativity based economic activities, such as advertising, architecture, arts and crafts, design, fashion design, audiovisual arts, performing arts, publishing, software creation, gaming, media, and content creators.

We agree with the argument that claims creative and artistic work has been traditionally seen a lifestyle more than a way to make a living, which frequently leads to an idealistic and false belief that creative people and artist are only dedicated to cultivating beauty and pleasure, which also translates into “the assumption that freedom and autonomy from social obligation is essential” (Lingo and Tepper, 2015). On the contrary, we strongly identify this group of people with the notion of creative workers tight to a critic perspective of precarity and disadvantageous working conditions resulting from neoliberal, meritocratic systems. A kind of workers that live in the edge of multiple economic activities, long work hours for low income, and most of them rarely related to creative or artistic influences from their family of origin. In other words, we are referring to a group of people that somehow and sorting a variety of difficulties, are making a living from their creativity lacking social and cultural capital that some could think about when speaking of artistic or cultural elites; as well as those lacking from institutional support such as Mexican strong but insufficient structures for education, creation, promotion, and distribution of arts and culture.

In this line of thinking, this paper embarks on the understanding of life and career decisions while facing the major global crisis our generations ever faced. To do it, our starting point is creative work as informal, freelance, self-employed based, which means low and unstable income, no social securities of access to healthcare, savings, or retirement plans. Nevertheless, it is a group of individuals highly educated on specialized professions-arts and creativity oriented. As a result this paper offers a classification of the two type of strategies and categories of activities our creative workers developed as a way to make a living, but most importantly, as their best effort to keep going on with their creative jobs.

Metropolitan area of Mexico City socioeconomic context

Mexico City and the metropolitan area is the main economic, financial, political, and cultural capital of the country. It is estimated that the total area includes 7,866 km2-which represents almost 5 times the size of Greater London. Within the region of Latin America this metropolitan area is among the four most populated urban developments along with Buenos Aires, Rio de Janeiro and Sao Paulo. That makes an approximate total population of 23,500 million, equivalent to 17% of the national population (OECD, 2015, p.5).

In terms of GDP, it is considered that the metropolitan area produces almost a fourth to the national total, becoming the most important pole of attraction for investment and migration because of employment opportunities, and quality of life it offers (OECD, 2015, p.5). As the main urban center, it gathers a lot of the cultural infrastructure of the country, such as museums, theaters, cultural centers, cultural industries, and professional art schools, which tends to centralize job offers and for creative professions in what some authors call creative clusters (Mercado and Moreno, 2011).

On average, the city has a medium wage of 7,253 pesos, which is related to range IV of an income scale calculated by the National Institute of Statistics, Geography and Information, as shown in Table 1. However, CONEVAL (2012) acknowledges that a person should receive around 32,000 pesos per month to cover comfortably their monthly expenses, and to stay out of economic vulnerability and social security, hence, to be considered middle class in terms living conditions instead of income measurements (Teruel et al., 2018). Therefore, this calculation leaves out some estimations that claim 90% of the total population would be within middle class segments (Ríos, 2020).

TABLE 1

| Range | Mexican pesos | American dollarsa |

|---|---|---|

| I | 0–3,037 | 0–147.74 |

| II | 3,038–5,366 | 147.9–261.3 |

| III | 5,367–7,142 | 261.41–347.86 |

| IV | 7,143–8,898 | 347.9–433.39 |

| V | 8,899–10,772 | 433.08–524.23 |

| VI | 10,773–12,985 | 524.71–632.45 |

| VII | 12,986–15,755 | 632.5–767.36 |

| VIII | 15,756–19,618 | 767.4–955.5 |

| IX | 19,619–26,197 | 955.17–1,275.43 |

| X | 26,198–55,000 | 1,276–2,678.83 |

Monthly income per family.

Currency exchange rate from Mexican pesos to American dollars, 4th October 2021.

Source: INEGI, 2020, Encuesta Nacional de Ingresos y Gastos de los Hogares: https://www.inegi.org.mx/temas/ingresoshog/.

Since 20th March 2020, World Health Organization declaration of a world pandemic, Mexico’s government imposed social distancing measures which included closing any public event and non-essential activities. One of the most damaged economic sectors were the living arts. More than 722 theaters, 10,407 museums, and above 2,060 cultural centers closed their doors for almost a year (b22 Secretaría de Cultura, 2021). The artistic and cultural sectors were highly impacted from the very beginning of the lockdown, and they have not fully recovered after more than 2 years from its beginning. As we stated before, working conditions for creative workers have been precarious for a long time, therefore the pandemic has been especially hard that were already precarious became even more irregular despite individual attempts to innovate and keep their creative jobs going through different strategies.

When the hiatus of public activities came by April 2020 it was not planned to last long, no further than a couple of weeks, therefore it was not considered that logistic adaptations were necessary to adjust the live and creative activities. However, as the time went by, and the isolation conditions remained present, it was clear that a different form of being present among the public was necessary, also important, and urgent to make an income as the creative activity would not resume soon.

With notorious delay, universities, and cultural institutions of all levels of government produced some strategies to be present in their communities and to somehow keep their contracts with workers already. But it turned out to be very difficult in the long run. Most of their strategies to keep them active were to transfer their creatives processes and products to digital platforms and free access through social media, but also to paid platforms. However, their technological availability and literacy was a challenge as they hardly have had the necessary equipment, good connectivity and most of all, the capabilities to use devices and produce creative products with good quality, attractive and engaging for the audiences.

Methodology and general data

This paper comes out of an ongoing comparative research project that investigates people’s everyday consumption practices, economic histories, and plans in four urban areas of the Global South: Philippines, China, Brazil and Mexico to provide elements to understanding of how globalized economic growth is transforming lives among low-income urban communities today. The project’s central proposition is that in emerging economies, sectors of the urban poor are undergoing an economic transition that has consequences not only for material wellbeing, but also for social status, identity formation and belonging. The world’s emerging economies appear to be producing new kinds of urban low-income cultures, which fit neither of the older social categories of “urban poor” nor “middle class.” Economic emergence is producing cultural changes: new economic opportunities, longer periods of residence in cities, more secure forms of housing, increased access to credit, and a deeper integration into mass consumer practices have become characteristics of some communities, which no longer fit comfortably into standard models of urban poverty developed by social scientists and policymakers in previous decades. However, existing research has not established whether people engaging in these new urban lifestyles are actually escaping from poverty, or whether urban poverty is taking on new cultural forms.

To date, investigation of these changes has rested largely upon the work of market researchers, economists, and policy-oriented sociologists whose quantitative data tells that national economic transition, family and labour migration and access to new forms of credit are enabling such households to become increasingly consumer-rich. Many members of the former urban poor increasingly live in ways that until recently were locally read as “middle class.”

Our chosen methodologies were based on qualitative approaches to analyse documents on multidimensional poverty indexes, and to read a broad assortment of realities and multidiscipline takes over the data. Besides, we went further a patchwork ethnography by understanding that “home” and “field” limits were totally diffused and mixed together during our pandemic fieldwork (Günel and Varma, 2020). For our research project it was the only way to understand our subjects’ work, reality and experiences. It included a process of texting, videocalling, visual material exchanging, subject descriptions and short and individual ethnographic visits that allowed us to approach our subjects’ lives. We planned a strategy that kept changing on the go, partly because the pandemic challenges, partly because of the many challenges our interviewees were facing, which we actively tried to avoid being a burden for them; but also, as researchers with academic, working, and social responsibilities, we as a team tried to go with the flow by being opened and prepared with alternative techniques to achieve our field work goals.

The fieldwork where this data was gathered took place between March and August 2021. The total sample included 15 interviews to independent creative workers. On average both groups find themselves in the VI range of income which represents a range between 524.1 and 632 USD dollars per month. So, in general terms, we planned to reach a group of people with jobs within the creative sector, considered somewhere within the low edge to middle class. The selected group includes six women and nine men.

The table below details the subjects of the sample and their creative jobs. Five of them do visual arts, five more work in performing arts, two of them do musical arts, two more dedicate to cultural management, and the last one to literary arts. As we move on to the data, we analyse their activities before the pandemic and how they managed to adapt to the circumstances created due to the pandemic, taking in account that none of them have family background on arts, cultural capital, or social networks in the creative and arts sector, and all of them describe their main source of income, or at least a good part of it, as freelance or self-employment work. In other words, these are creative workers defining precarious work, living an scenario that was already unthinkable but certainly showing that it could always get worse. Table 2 shows details on the subjects and their creative jobs. Five of them do visual arts, five more work in performing arts, two of them do musical arts, two more dedicate to cultural management, and the last one to literary arts. As we move on to the data, we analyse their activities before the pandemic and how they managed to adapt to the circumstances created due to the pandemic, taking in account that none of them have family background on arts, cultural capital, or social networks in the creative and arts sector, and all of them describe their main source of income, or at least a good part of it, as freelance or self-employment work. In other words, these are creative workers defining precarious work, living in a scenario that was already unthinkable but certainly showing that it could always get worse.

TABLE 2

| Alias—gender—age | Occupation | Educational attainment | Type of employment | Monthly family income range |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Antonio—M 23 years | Journalist | Bachelor of arts (Literature) | Freelance | VI |

| Adriana—F 27 years | Cultural Manager | Bachelor of Dance Master’s in production PhD on production | Freelance, self employed | X |

| Carolina—F 29 years | Graphic communication | Bachelor of Visual Graphic communication | Freelance | IX |

| Fernando—M 30 years | Dancer | Bachelor of Dance | Freelance | III |

| Edith—F 30 years | Photographer | Bachelor of Communication Science Master on Arts and Design | Freelance, part time job | X |

| Gustavo—M 31 years | Graphic designer (employee) | Bachelor of Graphic Design | Freelance | V |

| Omar—M 31 years | Dance student | Bachelor of Dance | Self employed | VI |

| Alberto—M 35 years | Musician | Bachelor of Business Administration | Freelance | III |

| Santiago—M 36 years | Cultural Manager | Bachelor of Cultural Management Master of Communication and Politics Postgraduate student PhD in Humanities | Self employed | IX |

| Carmen—F 37 years | Children’s Entertainer | High School | Freelance, self employed | IV |

| Ernesto—M 38 years | Musician | Bachelor on Musical Instrument | Freelance | I |

| Celeste—F 39 years | Graphic designer | Postgraduate student in Master of Design and visual communication | Freelance | VI |

| Federico—M 45 years | Street artist | Bachelor of communication | Freelance | V |

| Mariana—F 53 years | Theatre actress | Bachelor of Theatre Arts | Freelance | VI |

| Ramón—M 37 years | Graphic designer | Master studies in Design and visual communication | Freelance | VII |

Interviewees.

Source: Own elaboration with data from project’s interviews.

Before social distancing times

Our group of interviewees had jobs in very different creative activities, from street clowns to graphic designers, writers, dancers, and musicians. It is important to notice that 14 of them have professional degrees, and four of them have pursued postgraduate studies. All of them have pursued creative activities for a long time and work hard on making their creative jobs the main income source; however, five of them have had to turn to teaching at any level to make ends meet often enough. Plus, another three of them would use their artistic/technical skills professionally in other fields, one as a reporter for a political party and the second one as a consultant for a cognitive communication company. There is also the case of a third person who has some training as a business administrator, yet he plays music professionally and has combined this endeavor with jobs as cultural manager. Also, before the pandemic two of the youngest participants of our study group were students at the end of their programs in Literature and in Dance, it was basically during the pandemic that they had to begin working in the artistic or another field.

This is a common trend going on even before the pandemic began, “[…] the workers develop in very unstable working conditions that do not offer what was considered as acceptable working conditions in previous decades. Benefits such as pensions, social security and stability are characteristics that hardly appear in creative industries jobs and are less frequently considered as real options for the students in these professions” (Castañeda and Garduño, 2017: 121).

Only two of the cases had the possibility to fulfill their household needs with their income coming from creative jobs, one on a PhD full-time scholarship, and another one working as a graphic designer for a large marketing company. This is a prevailing situation even before to the pandemic crisis, but the crisis certainly challenged even more their ways to earn their income and their turn to other activities to survive.

“I have a CONACYT grant, so [the pandemic] did not cause me too much of a struggle, because prior to this I was getting my masters. Then well, this is a steady income, in contrast with people who lost their jobs or had to change their sources of income. Well, honestly it was not much of a blow to me, because I also had savings. So, this has not really got me into trouble” (Santiago, April 2021).

In this first case, becoming a full-time student of a highly recognized postgraduate program has given him financial stability over the past few years. Therefore, in these circumstances, the pandemic has not affected him directly. In a second case, Ramon talks about how he has improved his working conditions by learning how to move around the field, also getting some recognition that has put him in a better place than before, when he did not know how to run the business.

“Now I have the luck to have found good jobs that have allowed me to improve my quality of life, more steadily. Besides, they gave me the chance to keep studying all the time.” (Ramón, April 2021).

On the contrary, most of our interviewees referred to the fact that their earnings decreased during the last year moving them downwards the national income ranges. Before the pandemic began, their income oscillated between range III and range X many of them having an earning closer to range VII. This has notably changed for the worst, as some of them even have gone unemployed and left with no income at all:

“Before the pandemic, I was in a X (income range), and now, we are on the bottom, like between IV and V. But, before the pandemic I was comfortably in X.” (Federico, August 2021).

They complement their income by teaching in formal or informal ways. Many times, this is a steady and reliable source of income, which tends to support their creative endeavors: “I’m a professional dancer and a teacher on the side” (Fernando, March 2021). Celeste claims: “When I was not teaching, I was working as a freelance illustrator” (April 2021). Some other had experienced precarious conditions before the pandemic and they refer to that as well:

“I’ve been lucky. I am a freelance designer, I have worked for agencies and have had the advantage of constantly having money on my pocket. Three years ago, it was very complicated for me, and now with the pandemic, I started to get better projects… I think I have been lucky, but 3 years ago, I would say it was very complicated. It depends a lot on the job I have.” (Ramón, April 2021).

But there are also cases that have been struggling for a while, before 2020: “The pandemic did not change anything for me. Nothing at all, my hardest year, financially, was 2019, when I had health problems.” (Carolina, March 2021).

When the pandemic arrived

An important indicator is that the number of self-employed individuals increased to 10 of them during the pandemic, some of them were laid out, many of them had to combine their creative jobs with teaching, and had to abandon the creative sector, at least temporarily. As it was already mentioned, face-to-face interactions were severely restricted. Among the activities affected profoundly by this decision were the live arts, leaving these workers without much to do to adjust their jobs. As Carmen mentions here:

“My husband was employed in a restaurant. He is a clown and was working on his show as a clown, magician, and balloon twisting. He had a salary, besides his tips. When all the restaurants closed, he went unemployed.” (Carmen, March 2021).

Within weeks, many of them found that the work they had planned for 2020 had disappeared almost entirely, especially when it had to do with live presentations in festivals, stage seasons, and other live shows.

“Now all of us are looking where we can get some income. Now we are not able to put an income together. We are frustrated, because now our gigs are stuck, and there is no support at all, no one, absolutely no one is supporting us, they do not even have any considerations for us.” (Ernesto, August 2021).

“As the schools closed, I did not have any classes left to teach. The same happened with performances, as the theaters closed, I did not have any more performances. Not even in the [dancing] companies I collaborate, it all stopped.” (Fernando, March 2021).

In general, income decreased and those who initially had considered themselves as middle class or at least being able to easily cover their expenses went into uncertainty, month by month, while the hope of reopening places, venues or any kind of public activity were being held for a long time.

Work and earning strategies to navigate the pandemic

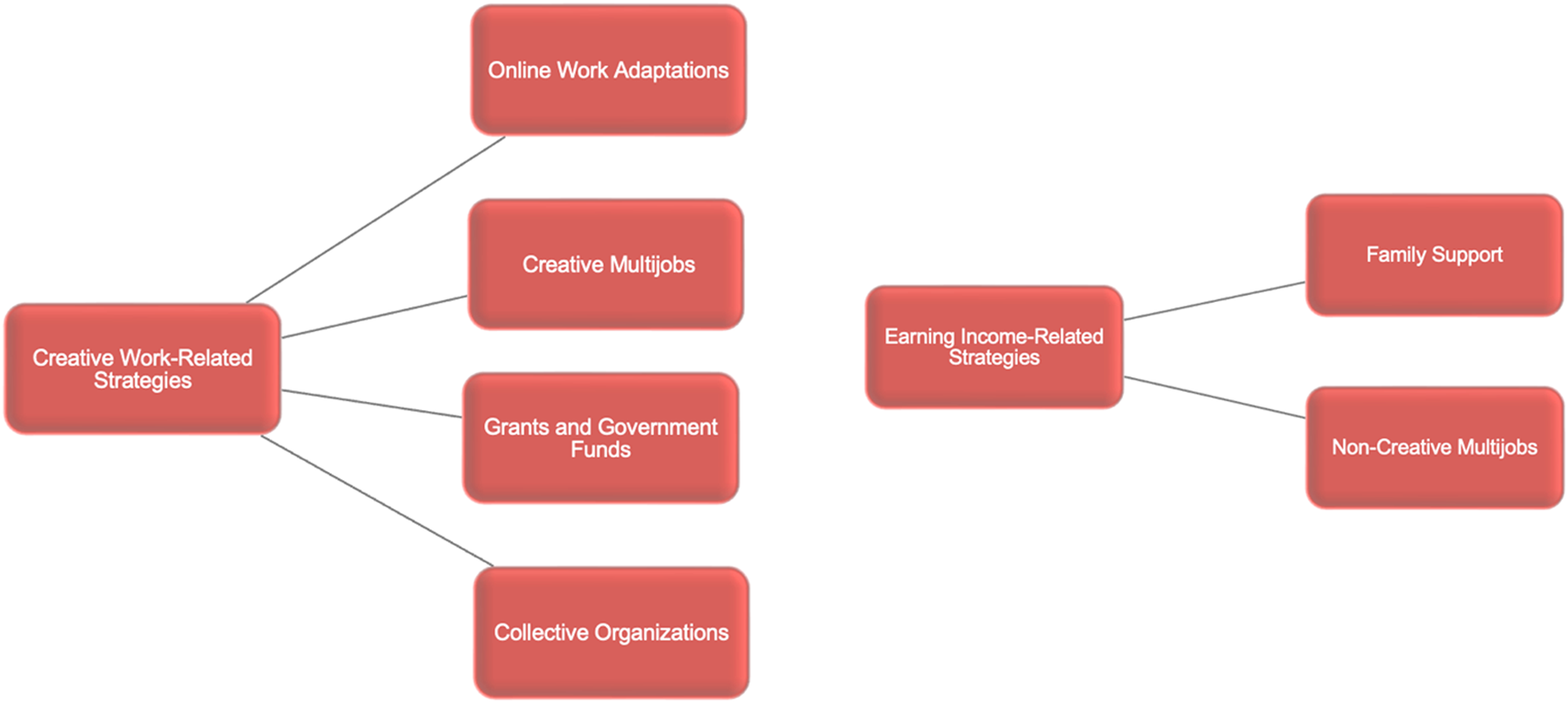

Among the challenges that COVID-19 threw at people were earning an income in spite of having their main income sources limited or fully reduced by mandate. We observe two types of strategies on which they seem to rely frequently and then six categories in which we can classify their main economic activities during difficult times. First type would be every activity related to trying to keep doing their creative jobs and staying in the creative field, such as digital technologies adaptations; collective creative work initiatives; grants and government funds applications; and multiple small jobs within creative fields. By doing this type of strategies their main goal is partly to have enough income, but most importantly to not abandon the field, because leaving, even only for a short period could threaten their achievements or worst-case scenario would make them leave permanently. Second type refers to every activity related to gather an income no matter it is outside the creative field. This type groups multiple jobs they have been doing explicitly to make a living; some of them hoping to get back to their latter jobs, but some other consciously facing the increasing possibility of leaving the field perhaps permanently. We can consider the family support or social ties (Paugam, 2012) that can be found in different ways and shapes as the most privileged strategy; and again, a variety of multiple jobs but completely out of the field. Figure 1 represents two types of strategies and economic activities creative workers relied on during pandemic social distancing periods.

FIGURE 1

Work and earning income strategies.

Creative work-related strategies

Online work adaptations were one of the first strategies back in March 2020, when the pandemic was supposed to last a few weeks at the most, their first response was to transition their usual activities to virtual formats, which had mixed up results. Visual artists, who were more familiar with working from a computer, had less issues adapting their activities to a digital mode. Some of them have already worked online or with digital platforms and devices, which made them more capable to go through social distancing times.

A graphic designer describes:

“At the beginning of the pandemic I worked from home, now I must go to the filming studio to work. I have done both. In my home is only the internet and my cell phone. My bill is only for the internet connection charge, I do not use a landline phone” (Ramón, Graphic Designer, April 2021).

But for others, the transition has not been as smooth. Many of them were not used to deal with digital technology every day, at least not to do their jobs, especially those dedicated to live arts:

“I was not interested in digital technology for a very long time because I took a chance and opted to be in face-to-face contact with people. The virtual world has swept me off my feet during the pandemic” (Federico, street clown, August 2021).

“I think next year, when all this situation of the pandemic would have already finished, or at least improved, I might invest a little in digital technologies, maybe getting a better the computer, or a laptop. Whatever I used to use, and my technology standards have changed a lot now, and now I’ve become a little more demanding” (Omar, folklore dancer, March 2021).

As a consequence of transitioning to digital technologies, most of them have modified their activities and adapted to their new tools, which many of them attempted to do with some success as they had little knowledge on how to use them, and more than that, they had not enough tools to get online because their internet connections and digital literacy was very limited.

“Last year, I bought some speakers, because I had a grant from FONCA. I need them to work, because now all is online, then as I knew I needed the equipment to be able to work online, well, then I used that money for it. But meanwhile, there is nothing, because it is hard, there is nothing, there are no concerts, no gigs, I had a few coming, but I got COVID, so the whole month of July I was confined to home” (Ernesto, pop musician, August 2021).

There is another case that found the way to turn the crisis, the digital transition, and his home confinement conditions into some earning strategy as a game streamer. It interesting that this kind of activity it is not putting a strain on his creative work, although it’s not related it keeps him doing another job in the limits of the creative field:

“I began to stream my games; it is where I play, and I get donations. I have not done that before. It was because of that extra time that I had. I do it regularly, two or three times a week” (Alberto, country musician and cultural manager, July 2021).

About getting small and multiple jobs within the creative field, Mariana is used to it, she is being pursuing her creative based career by jumping from project to project, but the pandemic enhanced the precarious working conditions she was already blinded to. This is a very common phenomenon in which creative workers appreciate their autonomy and freedom to create under their own schedules, but pandemic made them face the precarity of their careers. They have found themselves jobless, stressful for illness threaten and powerless with no health insurances or savings to go through the crisis. Non-etheless, Mariana has a long trajectory and was able to get to teach private classes:

“Well, I guess I have gotten some tiny projects here and there, and less frequently, but I have gotten some. I cannot complain. I also have gotten some voiceover projects. Besides, last year, I got some face-to-face classes in June, I took them with all the precautions, and we completed four classes in June. This year I got eight more, four on Monday which was face-to-face, and 4 more on Tuesday which was online classes. I also got a tv commercial… very short, morning shooting, like 4–5 h, I got Covid tested at the beginning of the shooting, we waited for a little while, started shooting, and that was it” (Mariana, actress and broadcaster, September 2021).

Before, but especially during the pandemic, we identified another source of income followed by their consolidation in the creative field, which is applying and eventually winning grants and prizes for their creative careers. Over the past 3 years, five of them have been nominated to earn a prize or grant, one of them winning in the dance field; one of them was granted a community project in his area of residence. One more was awarded by an international children literature festival outside the country, along with some mentions in other festivals; also winning a small grant during the pandemic to produce music for the National Secretariat of Culture and an award for his thesis on promoting the eradication of violence and discrimination in the city.

Although these grants are somehow large amounts of money, and some of them have a positive impact in their careers, they hardly get to improve their working conditions in the long run. Symbolic advantages are also present, like consolidating their statuses as creators and getting legitimacy and recognition within the field. It also means potential contracts in the future, projects, and good opportunities to keep creating and working on the creative sector. On that respect Roman claims: “a revision of the Mexican cultural policies shows that there is a void and disdain for the artist, that generates many of the cultural products that the country wants to protect. So, since the creation of FONCA in 1994, the artists can make a career through the grants, scholarships and funds for production, creativity development, education and training, research, and promotion are actions for the short term” (Román, 2013: 220).

Finally, we had the chance to acknowledge collective organization experiences as a result of insufficient political actions and State intervention to support the field during social distancing and creative work extreme limitations. At least two of our interviewees referred to have been working with self-management collectives that either generate work projects or incorporate political pressure as one of their core values. This kind of collective organizations are doing a laudable work. We consider this is one of the civil society actions that are very promising in the short term and look forward to following them closely.

“So, I am part of a group called ‘Ink Society,’ we are a group of creative women. We got together at the invitation of one of us and we started talking and realized that there was a series of problems we face as illustrators… We usually share project calls on our page, we review them because we do not want to share the kind of calls where you are paid only with recognition (and no money).” (Carolina, illustrator, March 2021).

Earning income-related strategies

Meanwhile, other ones had to look out for other economic activities to survive, as the social distancing measures closed live and public events. The stage artists of our group found alternative sources of income that came from social ties such as family support, family-based business or some other earnings coming from their family assets. This way they could cover monthly rent payments, food, and basic expenses.

“It took us a good while to stabilize ourselves because of the pandemic, we sold a lot of things, we sold a car, my brother’s house in Veracruz was put on rent, all we could sell was sold. Before watching for ourselves, we were watching for the people who were working with us, it was very complicated.” (Adriana, cultural manager and folklore dancer, March 2021)

Many of them turned to start selling highly demanded products that were vital to live under a pandemic, such as groceries from local sources, homemade food, sanitizers, surgical gowns, and COVID-19 face masks.

“And now since the pandemic began, I am starting to sell some products of a brand called LIFE PLUS, that also has a toothpaste without fluor. Then, with the earnings from these sales I am starting to buy more products, LIFE PLUS, because now I sell them.” (Ernesto, pop musician, August 2021).

“I used to have a [financial] cushion. At the beginning of the pandemic, I had enough savings to live for a few months comfortably. Then I started selling protection masks and I made enough for another year. It is only now that I am noticing some shortages” (Federico, street clown, August 2021).

Another very important source of support that comes in different shapes and forms is the one provided by parents, siblings, partners and ex-partners, and it proved to be very reliable. In 13 of the 15 cases, we identified constant help from their communities to sort out their financial situation. The recurrent ways to help them out, are through housing, paying medical bills or providing some cash to cover extraordinary expenses or even regular ones; sometimes, the income coming from their social ties is used to support their creative projects. Some of these strategies are present in the following narratives.

“I bought this apartment and was paying for it by myself; it was a very good opportunity that is why I went for it. Now honestly, I am getting my family support to pay the installments. At the beginning I used to think I would not be able to keep paying. That was my concern. But I have managed to pay it for a while. And then, when I enrolled to my master’s program, I got my family support.” (Celeste, graphic designer and part time lecturer, April 2021).

“I used to rent an apartment with roommates before, but the pandemic made me go back my parents’ home” (Gustavo, graphic designer, March 2021).

“I get private medical insurance through my mother. She told me: ‘Look, I am paying for your father’s insurance and mine, and I can include yours too.’ Our thought was that I am freelance designer, and I do not have social security.” (Ramón, illustrator, April 2021).

“I work on the show business, and my dad is my partner. He is the investor” (Adriana, cultural manager and folklore dancer, March 2021).

“We have been a couple for ten years, although we are not living together. Unlike many of my colleagues, I’m lucky he helps me out. He never lost his job, he never stopped working and he is helping me out with a monthly stipend. I have zero earnings; I am not receiving anything at all from acting.” (Mariana, actress and broadcaster, September 2021)

Conclusion

As it is possible to observe, the pandemic had a real negative impact in the life of these creative workers as their income decreased importantly. Their previous situation was already precarious, even before the pandemic arrived in Mexico. Therefore, their different ways to gather an income is a very important aspect of their biography and professional career that can explain how they navigate the COVID-19 storm. Although most of them already had to be creative not only because their jobs are based on creative occupations but because it is an economic sector that is distinguished for the precarity of its employment offers, especially to the younger generations as to those who have had less exposure to the creative sector market and therefore have less skills to navigate the circumstances. Therefore, their strategies to make a living out of their creative careers even before the pandemic were already to do multiple jobs on different fields, but the current global economic situation has worsened the scenario, their employment options, and their status in the creative sector labour market. The current conditions have created even more avert living conditions and disparity than before. The important increase of the self-employment points out to further precarity, which also enhances the already existing inequality bridges, with no better conditions in the years to come.

This situation had an impact in their chances to be employed in creative activities during this period and in some cases almost entirely deviated them from their creative pursuits, making even more real the fact that they are part of an economic sector characterized by the fragmentation and precarity of the labour market offers and the working conditions. Thus, multiple jobs strategies make a permanent alternative and not temporary as the would desire; it has become even more evident and necessary to them.

Something that is evident is that they have employed more hours of their work to achieve the same number of results or even less given their lack of digital technology literacy or the lack of good enough equipment and connectivity to make their creative work more viable and improve their quality. In some cases, they do not seem to be catching up with the fast-changing digital technologies, if anything this seems to be creating greater disparities between those who can afford and have the ability to access updated devices, platforms and software.

The uncertainty on what the future will bring, on how and when the health conditions will improve locally also have an impact in their work, because they cannot really plan in advance and produce good conditions to foresee new creative projects in due course. This situation has an impact on their pocket but also in their way of thinking of creative jobs and their vulnerable presence in the field. Although this is only an explorative approach to a small group of interviewees, this research shows how the creative expressions have been hit and decreased possibilities to growth their importance and legitimacy on the labour market; on the contrary, working and living conditions for the creative workers are not expected to improve in the short term. It seems highly likely that many of them will not be able to go back to the creative and artistic sector, at least not on the same terms, doing what they know best, what they are passionate about, and what they have imagined as their life plan and career.

Statements

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct, and intellectual contribution to the work and approved it for publication.

Acknowledgments

For the development of this paper, we would like to thank the Australian Research Council, Western Sydney University and University of Technology Sydney for providing and managing the funds for the research project. We thank Dr. Anna Cristina Pertierra (University of Technology Sydney) who invited us to join the team. Also, we appreciate Maribel Montufar and Manuel Acevedo’s hard work on putting this paper together.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Footnotes

1.^Consejo Nacional de Evaluación de la Política de Desarrollo Social is a Mexican organization coordinated by the Secretariat of Welfare with autonomy to evaluate social policy.

2.^Consejo Nacional de Ciencia y Tecnología is a government fund for science and technology development.

References

1

Castañeda E. Garduño B. (2017). Mapa de las industrias creativas en México. Proyección para CENTRO. Econ. Creat.07, 117–162. 10.46840/ec.2017.07.05

2

Cobos E. P. (2016). Zona metropolitana del valle de México: Neoliberalismo y contradicciones urbanas. Sociologías18 (42), 54–89. 10.1590/15174522-018004203

3

Comunian R. England L. (2020). Creative and cultural work without filters: Covid-19 and exposed precarity in the creative economy. Cult. Trends29, 112–128. 10.1080/09548963.2020.1770577

4

CONEVAL (2012). Pobreza urbana y de las zonas metropolitanas de México. Ciudad de México: CONEVAL.

5

Florida R. L. (2002). The rise of the creative class: And how it’s transforming work, leisure, community and everyday life. New York: Basic Books.

6

Günel G. Varma S. (2020). “A manifesto for patchwork ethnography,” in Member voices, fieldsights,in society for cultural anthropology. Available at: https://culanth.org/fieldsights/a-manifesto-for-patchwork-ethnography.

7

Lingo E. L. Tepper S. J. (2013). Looking back, looking forward: Arts-based careers and creative work. Work Occup.40 (4), 337–363. 10.1177/0730888413505229

8

Mercado A. Moreno M. (2011). La Ciudad de México y sus clústers. Juan Pablos Editor: México: Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana.

9

OECD (2015). OECD Territorial Reviews: Valle de México. México. Paris: OECD Publishing. 10.1787/9789264245174-en

10

Paugam S. (2012). Protección y reconocimiento. Por una sociología de los vínculos sociales. Papeles del CEIC, Int. J. Collect. Identity Res.2, 2. 10.1387/pceic.12453

11

Piedras E. (2004). ¿Cuánto vale la cultura? Contribución económica de las industrias protegidas por derechos de autor. Ciudad de México: SACM, SOGEM CONACULTA. Available at: https://sic.cultura.gob.mx/documentos/1233.pdf.

12

Ríos V. (2020). No, no eres clase media. The New York Times. From: https://www.nytimes.com/es/2020/07/06/espanol/opinion/clase-media-mexico.html (Accessed July 06, 2020).

13

Román L. (2013). “El pluriempleo y la precariedad laboral de los artistas escénicos en la Ciudad de México. Una aproximación,” in Cultura y Desarrollo en América Latina. Editors País,M.MolinaA. (Argentina: Ediciones Cooperativas).

14

Secretaría de Cultura (2021). Sistema de información cultural. Available at: https://sic.gob.mx/index.php.

15

Teruel G. Reyes M. Minor E. Lopez M. (2018). México: País de pobres, no de clases medias. Un análisis de las clases medias entre 2000 y 2014. El Trimest. económico85 (339), 447–480. LXXXV. 10.20430/ete.v85i339.716

16

UNESCO (2010). Políticas para la creatividad. Guía para el Desarrollo de las industrias culturales y creativas. UNESCO. Available at: https://es.unesco.org/creativity/sites/creativity/files/220384s.pd.

Summary

Keywords

Creative workers, work strategies, precarity, cultural industries, pandemic adjustments

Citation

Molina A and Garduño B (2022) Work strategies developed by creative workers in Mexico City: Enhanced precarity and adjustments during pandemic social distancing periods. Eur. J. Cult. Manag. Polic. 12:11087. doi: 10.3389/ejcmp.2022.11087

Received

19 May 2022

Accepted

01 December 2022

Published

19 December 2022

Volume

12 - 2022

Updates

Copyright

© 2022 Molina and Garduño.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Ahtziri Molina, ahtziri@gmail.com; Bianca Garduño, bigarduno@gmail.com

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.