- 1Department of Economics, Management and Business Law, University of Bari Aldo Moro, Bari, Italy

- 2Department of Economics and Management, University of Ferrara, Ferrara, Italy

Considering their focus on participation and sustainable tourism promotion, ecomuseums can play a crucial role in the sociocultural development of local areas. Through three exploratory case studies of Italian ecomuseums located in the Emilia-Romagna region, this study shows the emergence of three different profiles of ecomuseum development strategies: they relate to the sustainable tourism, the cultural districts, and the holistic approach to sociocultural development. These kinds of strategic profiles not only emerge in opposition to each other but can also overlap and appear jointly within different situations of ecomuseums. The final aim of this work is to reflect on the applicability of management tools to support the implementation of these strategic aspects, especially in the current scenario, in which new perspectives are emerging about the role of communities in interpreting and enhancing their tangible and intangible cultural heritage in relation to sustainable tourism and local development linked to cultural and natural heritage preservation and promotion.

Introduction

The ecomuseum is a concept that originated in the early 1970s as part of the process of innovation in traditional museology, which was called “new museology” (Ross, 2004). The conceptualization of ecomuseum is due to de Varine (1978), but later, it was developed and further analyzed by other important scholars, such as Riviere (1985), Corsane et al. (2007), and Davis (2011).

It is a well-established notion, and its usefulness appears to be valid, as the concept of ecomuseum is closely interrelated with those of community engagement (Choi, 2017) and sustainable tourism (Bowers, 2016). Another concept that can present important points of contact with ecomuseum is the cultural district, which Santagata (2002) defined as an industrial district where culture and cultural heritage are the dominant factors. All these concepts appear to be very topical today; indeed, in recent years, their centrality, both in the academic debate and in real life, has grown significantly. Moreover, recent academic studies have reported a growing diffusion of ecomuseums in Spain (Corral, 2019), North America (Sutter et al., 2016), and generally worldwide, with a particular increase in developing countries (Wuisang et al., 2018). Ecomuseums also represent an important reality in Italy, especially in some regions where they have received legislative regulations (Santo et al., 2017) aimed at strengthening their role in the development of local communities.

In light of these considerations, the debate on the role of ecomuseums has also seen interesting recent developments. At the same time, from the point of view of the diffusion of concrete ecomuseum experiences, the last few years have shown an important recovery: numerous academic studies, in this regard, recall the recent growth of the phenomenon (Belliggiano et al., 2021; Tsipra and Drinia, 2022). This element is interesting since after an almost constant growth in the diffusion of ecomuseums in the last decades of the past century, a slowdown of this trend was subsequently recognized (Maggi, 2006).

Therefore, various scholars have analyzed the role of ecomuseums in museum studies (Davis, 2008), their importance for the development of communities (Doğan, 2019; Pappalardo, 2020), particularly in rural areas (Ducros, 2017), the relationship between the development of ecomuseums and sustainable tourism (Bowers, 2016; Belliggiano et al., 2021), as well as that between this form of museum and the promotion of community participation in cultural heritage management and policy (Sokka et al., 2021). Furthermore, ecomuseums fit very well in the European Union (EU) framework for action on cultural heritage (European Commission, 2019), as well as in the current European policies that place culture and cultural heritage in the context of the European Green Deal (European Commission, 2022).

Nonetheless, to the best of our knowledge, the subject of how the development of ecomuseum strategies can be made more effective by the application of managerial tools still appears to be underdeveloped. Therefore, the present study tries to fill this research gap through the analysis of managerial profiles that can make the development of strategic profiles for an ecomuseum more effective.

The achievement of this objective has declined through the proposal of distinct case studies, according to the qualitative research method of multiple case studies (Stake, 2006). Consistent with this, three cases of Italian ecomuseums from the Emilia-Romagna region were subjected to analysis. The approach that has been used is exploratory (Yin, 2018), which means that the basic idea is the definition of a framework of hypotheses on possible managerial tools. The analysis of the case studies, which considers the evolution of the three ecomuseums in recent years, also includes the COVID-19 pandemic period, which tested the ability of each ecomuseum to keep its communities united at a historical moment in which the sense of loneliness and disorientation of many people was significant. According to these hypotheses, which will be subjected to further study in future research, managerial tools, if implemented, could favor the effectiveness of strategy implementation in ecomuseums.

Theoretical framework

The ecomuseum has been described by many authors and scholars in several circumstances, as already reported in Badia and Deodato (2015). One of the most famous definitions is that of Riviere (1985: p. 182):

An ecomuseum is an instrument conceived, fashioned and operated jointly by a public authority and a local population. The public authority’s involvement is through the experts, facilities and resources it provides; the local population’s involvement depends on its aspirations, knowledge and individual approach. It is a mirror in which the local population views itself to discover its own image, in which it seeks an explanation of the territory to which it is attached and of the populations that have preceded it, seen either as circumscribed in time or in terms of the continuity of generations.

De Varine, who is credited with the invention of the term, has stressed some important elements of the concept of ecomuseum on several occasions. First, “the ‘eco’ prefix to ecomuseums means neither economy, nor ecology in the common sense, but essentially human or social ecology: the community and society in general, even mankind, are at the core of its existence, of its activity, of its process. Or at least they should be… This was the intuition of the “inventors” of the ecomuseum concept in the early 70s…” (de Varine, 2006: p. 60).

Again, De Varine noted how, in the years following its first definition, the ecomuseum has assumed two different paths in practice, partly opposite each other (de Varine, 2002). The original definition aims to highlight the link between the museum and the natural environment toward a concept similar to a museum park. Simultaneously, around the early 1980s, a concept derived from ecomuseum has been developing, notably because of the experience of Le Creusot in France, as a museum becoming an instrument of community development.

This path of distinction between different forms of ecomuseums on a global scale has widened over the years. Currently, therefore, types of museums that are also very different from each other are called “ecomuseums” (Davis, 2011). In this diverse picture of concrete cases and practical realities, some common elements seem to emerge and essentially refer to the mission of the ecomuseum.

Maggi (2006): p. 63 noted that “almost all ecomuseums, even when using different denominations, have a particular mission: they try to promote sustainable development and citizenship through local heritage and participation. The most relevant obstacles they face seem to be the same almost everywhere: people involvement, effective leadership and the continuity of the initiatives.”

Cogo (2006): pp. 97–98 developed this concept by explaining the most important points of the ecomuseum mission:

- the safeguarding and valuing of local socio-cultural traditions; - the safeguarding/rediscovery of collective memory in terms of the intangible heritage comprising the identity of a population, and its mediation with contemporary society; - the study, research and dissemination of local naturalistic, historical and social topics; - the promotion of sustainable economic and tourist development, by using natural and historic resources, the social heritage and other local resources, via a network able to attract tourists and the additional exploitation of cultural resources; - the promotion of socially responsible business enterprise and the active participation in processes of sustainable growth.

Two main features seem to characterize the mission of an ecomuseum: the support for the advancement of sustainable tourism and the active promotion of civic participation in cultural heritage management development. The ecomuseum can be part of an implementation strategy of sustainable tourism—not without difficulties (Howard, 2002)—when it is able to promote its activities toward visitors and tourists (Belliggiano et al., 2021), enhancing its specific connection with the local area through the promotion of values that reflect its identity (Bowers, 2016; Simeoni and De Crescenzo, 2018).

Sustainable tourism combines the paradigm of sustainability with economic development based on tourism (Hunter, 1997). Sustainable tourism is not aimed at unlimited growth but is consistent with the enhancement of existing resources. In its various forms, an ecomuseum project explicitly aims to initiate socioeconomic activities compatible with the logic of sustainability. Specifically, tourism is sustainable if it is developed as environmentally friendly, economically viable, and socially equitable for local communities; in other words, it refers to a level of land use that can be maintained in the long term, as it produces economic, social, and environmental benefits for the area in which it is implemented.

For example, at the economic level, the positive impacts of sustainable tourism can be identified in job creation on the site, in the redistribution of income, and in restraining the depopulation of rural areas. In addition, sustainable tourism can reduce some negative social effects of “traditional” tourism, such as its seasonal nature, the weight of external tourism companies that do not have a direct impact on the territory, the instability of local revenues, and transport and infrastructure development oriented only to tourists and not to local people. From an environmental point of view, sustainable tourism is concerned with reducing, if not breaking down, the negative impacts of traditional mass tourism (e.g., depletion of natural resources and pollution).

In summary, sustainable tourism satisfies both the needs of the local community in terms of quality of life and the demand of tourists, protecting cultural and environmental resources, maintaining a certain degree of competitiveness, and promoting the phenomenon of solidarity tourism through a relevant role of the ecomuseums (Doğan, 2019).

Another relevant key feature of the ecomuseum mission is favoring citizen participation in paths of local development through the enhancement of cultural heritage. Participatory approaches appear particularly appropriate for cultural heritage management. Relevant international institutions have already claimed the importance of community engagement in cultural heritage management and development since the beginning of this century (UNESCO, 2002; Council of Europe, 2005; European Commission, 2019). Academics and professionals in cultural management suggested multistakeholder governance models (Bonet and Donato, 2011), even considering the opportunities of a collaborative governance approach (Jeon and Kim, 2021).

Participation can be considered a challenging task when establishing an ecomuseum. In fact, an ecomuseum can promote a greater sense of collective ownership, more community-led initiatives, and a process of appreciating, supervising, and safeguarding the interactions between people and the environment (Choi, 2017). These processes can assume particular relevance in disadvantaged or depopulated territories, such as rural areas (Ducros, 2017; Bindi et al., 2022).

With reference to the development of specific participatory practices in the context of ecomuseums, community (or parish) maps (Clifford and King, 1996; Parker, 2006) emerged as one of the most widely used tools for ecomuseums. Community maps are instruments through which residents can expose their own representations of cultural heritage in its broadest sense, including the landscape, knowledge, and traditions of the place. These processes are fundamental for reinforcing the sense of awareness and identity of a community (Guaran and Michelutti, 2021).

The map of the community is also a place of memory, as it sheds light on what people want to pass on to future generations. Specifically, it normally consists of a cartographic representation (or any other composition inspired by that logic of representation) in which the community can identify itself. The basis of the abovementioned knowledge and understanding can still lead, secondarily, to the development and eventual rediscovery of gastronomic production and handicraft traditions, which could even allow the promotion of the territory and its products through the active involvement of the local community.

Although these two aspects (i.e., the development of sustainable tourism and the promotion of citizen participation) appear to be the most typical features linked to the development strategies of an ecomuseum, a third possible characteristic element can be identified: the promotion of a cultural district linked to the territory of which the ecomuseum wants to be an expression.

The cultural district stems from the concept of an industrial district (Becattini, 2004), which is defined as a local production system characterized by a high concentration of industrial companies specializing in that industry sector. Therefore, the cultural districts can be seen in an industrial district in which culture and cultural heritage are the dominant factors (Santagata, 2002: p. 15):

The content of the goods produced in these districts is strictly connected to the local civilization and savoir vivre. Furthermore, the economic advancement of these products is naturally correlated with the local culture: the more their image and symbolic icon is identified with local customs and cultural behaviors, the more they seduce consumers (cultural lock-in) and the more their production is fostered. In this case, the importance of culture is all-inclusive, mobilizing the aesthetic, technological, anthropological and historical content of the district.

The perspective of the cultural district takes on value for an ecomuseum because it enhances the need for collaboration between stakeholders as an essential element for its development (Arnaboldi and Spiller, 2011). This represents an approach to local development, where cultural production and participation play a central role in local development through integration with other economic sectors of the local area. In this context, culture can become a constitutive element of economic and social growth, based on social and environmental sustainability, in its ability to promote the elements of human, social, symbolic, and cultural capital linked to the founding values of the territory concerned (Sacco et al., 2013). With reference to cultural districts, the literature has shown the complex dynamics of management and governance that can favor their development (Schieb-Bienfait et al., 2018), also because the cultural district sees the involvement of a plurality of subjects, both in the public sector and in the private sector, whose government may require the development of collaborative governance paths (Gugu and Dal Molin, 2016).

Although the subjects related to the development of the ecomuseums seem to have assumed a good rate of advancement (Liu and Lee, 2015), the presence of research works that analyze the possible role of management tools to support these processes effectively appears rather limited. Considering this framework and the emerging research gap, this paper aims to develop the following research questions:

1) Which concrete ecomuseum development strategies emerge in the current context?

2) Which management tools should be adopted to increase the effectiveness of these ecomuseum development strategies?

Methodology

The research method employed multiple case studies (Stake, 2006). The basic idea for using this method relates to the purpose to obtain, thanks to replication, the possibility of enriching the proposed considerations in compliance with the necessary methodological rigor (Eisenhardt and Graebner, 2007): replication indeed leads to comparison, which allows the initial theoretical concepts and the relationships established between them to be developed in more detail (Yin, 2018).

For this multiple-case study, three cases were selected. The choice fell on three ecomuseums belonging to the same territorial context (Emilia-Romagna, Italy) to favor a basic homogeneity of context, which is a necessary element for obtaining at least partial replicability of the research, which is an essential reference in multiple case study research. At the same time, these ecomuseums presented certain profiles of differentiation, which justify the multiple approaches that will be examined in the next section.

The three cases are the Ecomuseum of Argenta (province of Ferrara), the Ecomuseum of Bagnacavallo (province of Ravenna), alternatively named as “marsh herb ecomuseum,” and the Ecomuseum of hill and wine of Castelllo di Serravalle (province of Bologna). The research in these three realities was conducted using the following research tools:

- Semi-structured interviews (Qu and Dumay, 2011) with the directors and/or the administrative staff of the ecomuseums. At least two interviews were conducted for each ecomuseum. Overall, eight interviews were conducted, and six subjects were involved. Each interview was conducted using a homogeneous methodology based on a series of open-ended questions. Every interview lasted between 60 and 90 min.

- Material analysis of additional documents, provided by the ecomuseum staff or available on the web, regarding the activities of the ecomuseums.

- Participant observation through one experience of direct participation by the researchers in the ecomuseum proposal for visitors/tourists. These visits were realized without the involvement of the directors of the three museums to live a more genuine experience, not developed ad hoc by the museum staff for the research perspective.

In the next section of the article, every case study will be presented, highlighting the following points:

- Introduction and brief history of the ecomuseum

- Governance and the role of the managing entity

- Most relevant activities

- Involvement and participation of the community

- Impact of COVID-19 on the activities of the ecomuseum

- Analysis of the economic fundamentals

- Special projects and future strategies

- Role of management tools in supporting strategic development and operational activities

However, these points represent only a trace of the following exposure and will not be analyzed exactly in this order but depending on how the different points have emerged during the semi-structured interviews.

Case studies

Ecomuseum of Argenta

The Ecomuseum of Argenta was founded in 1991 with its first component, the Museum of the Valleys, following the will of certain groups of associations in Argenta to enable projects of restoring the environment and the river around the oasis of Campotto, territories belonging to Po Delta Park. Then, between 1994 and 2002, the ecomuseum was extended with a second component, the Museum of Land Drainage, at the water pump of Saiarino, which is the heart of the hydraulic system of the government of the waters between the Apennines and the Adriatic Sea. Finally, in 1997, the ecomuseum was completed with the third component, the Civic Museum, conceived as a center for representing to visitors the history of the town of Argenta and its urban landscape. The Ecomuseum of Argenta is directly managed by the Municipality of Argenta, a city of 20,000 inhabitants, in the province of Ferrara. The director is an employee of the municipality. The ecomuseum has three other employees (one full-time and two part-time), as well as further cooperation with external professionals and a cooperative. The director has a good degree of autonomy in her management decisions.

The Ecomuseum of Argenta gained official recognition for its role by the Council of Europe and, on a regional scale, obtained the label “quality museum,” which means that it respects predetermined quality standards of museum management. This ecomuseum is based on integration throughout the territory between the local landscape and the three museum locations. The Ecomuseum of Argenta is hosted by a lagoon landscape inside the intensively cultivated Po valley close to the delta of this river. This landscape presents issues related to biodiversity, sustainable farming, and traditions of manufacturing linked to the agrarian sector. In the specific case of Argenta, the ecomuseum assumes participatory functions for social and economic development by different actors in the local area. The Ecomuseum of Argenta can be defined as an internal agreement of the local community to take care of the territory. Therefore, the fundamental objectives that form the basis of the ecomuseum are mainly related to the sociocultural development of the territory and to increasing the level of awareness by the citizens of its values, history, and local traditions.

In this sense, participatory processes have been conducted by the instrument of the community maps in Campotto, Benvignante (hamlets of Argenta), and, in a more simplified way, other areas of the municipality of Argenta. Then, executive actions were implemented. For example, a space dedicated to the repopulation of native fish (such as pike, tench, and carp) was created, and new alliances were developed with companies, consortia, and associations of the agricultural and fishing industries.

Another interesting participatory project can be called “participatory archeology.” Following a recent discovery of an archaeological site of the Roman age in the area, the ecomuseum brought together associations and citizens with public initiatives, cycles of conferences, and courses with the high schools of Argenta, which continued despite the difficulties of the pandemic period. The result has been that the locals have begun to take an interest in the archaeological heritage of the area, to make reports, and to feel truly involved in these discoveries.

In parallel, the ecomuseum has enabled networking systems with restaurants for the revaluation of the gastronomy of the valley, with the reintroduction of the specialties of freshwater fish and the use of wild herbs in the kitchen. The economic boom of the 1960s and the extensive agrarian reform deleted these elements, favoring the consumption of sea fish and plant species that were alien to local traditions. Still, the ecomuseum is working for the rehabilitation of inland water navigation by electric boats with flat-bottom keel, which retools the historic “Batana” used both for monitoring fish and for natural excursions.

Among the initiatives and activities of the ecomuseum, an important role is played by the activities of restoration and enhancement of cultural and monumental heritage. In particular, Benvignante, a Renaissance village dominated by the residence of the Dukes of Este (this residence is part of the UNESCO recognition of the site of “Ferrara, City of the Renaissance and its Po Delta”), is at risk of dropping, along with the campaign and the rural village. After the earthquake of 2012 in this local area, which damaged Este’s residence, there was a first restructuring in 2011 and a second restructuring between 2014 and 2015. These actions were linked to the implementation of the community map. Another goal of Benvignante’s map is to build a basket of typical gastronomy products, thus restoring knowledge, taste, and culinary innovation, with the identification of specific target markets. In the future, the residence will be equipped with kitchens and will be used for testing taste from gastronomic associations, agricultural and catering, and hospitality schools, with a link to the annual fair of the ecomuseums.

Other areas of the municipality of Argenta, which are located near the Valli di Comacchio and the Romagna, are characterized by biological fine dining with short production and distribution lines, such as the golden tomato; the cereal crops of wheat, barley, and spelt, derived organic flour and the incipient production of craft beer that emerged from Renaissance treatises of the Este period; and the typical “wines of the sands” and of the Bosco Eliceo. The artisan companies in the territory of the ecomuseum move in terms of knowledge and skills, specifically yarns, wool, and handcraft. This is the tradition of tailoring and knitwear factories, which were important in the years of the economic boom for women’s employment. These elements also emerge from the community map of Campotto, with the tradition of mulberry and silkworm breeding, silk yarn, and domestic wool, which engaged families and neighborhoods in partnership. Today, these skills have left silk but still emerge in other fields, such as diverse tailoring and wool.

A prominent role in the activities of the ecomuseum is occupied by networking activities with other institutions in neighboring territories. The most important initiative in this regard appears in the Constitution of the Centro di Educazione Alla Sostenibilità (Center of Education for Sustainability) (CEAS), which, in 2013, was set up as a network with other neighboring municipalities as part of a regional project for the promotion of institutional networks aimed at the development of sustainability in the territory. This center has assumed the name of CEAS “Valleys and Rivers” and is headquartered at the Ecomuseum of Argenta. The partners are identified, in addition to the Municipality of Argenta, in other neighboring municipalities (Mesola, Comacchio, Ostellato, and Portomaggiore). In addition to having importance from the point of view of establishing relations and exchanging experiences, the CEAS has also become a center of attraction for public funds, particularly from the Emilia-Romagna Region.

Finalizing the analysis of the main projects of the Ecomuseum, specific attention has also been given to educational projects, with constant attention to the relationship with the teachers and the schools in the area. In recent years, many initiatives have been developed aimed at creating itineraries for tourists and local inhabitants. The meaning of these itineraries is to make visitors discover the tangible and intangible heritage of the area. The main project concerns the Primaro route, from the name of a branch of the Po River—the longest river in Italy—which crosses the territory. The Primaro route traces a geographical route and connects it to all the naturalistic, historical, and economic emergencies along the route. Thus, while walking along the Primaro route, the story of Argenta is told from its origins to the present day.

The COVID-19 pandemic, although it has forced a slowdown in some cases, mainly due to the closures ordered for the museum venues, as established by national legislation in the most acute periods of the pandemic, has not had only negative impacts on this plenty of activities. The presence of outdoor nature trails has, in fact, been a reason for many people to rediscover itineraries when the rules on social distancing only allowed outdoor activities and prevented indoor activities. As for many other museums—somewhat around the world—the pandemic period was an important moment for ecomuseum managers to propose online activities and discover the opportunities provided by digital technologies. In this way, during the pandemic period, the Ecomuseum of Argenta played an important role in meeting the need for sociality in its community.

Moving on to a brief analysis of an economic nature, the Ecomuseum of Argenta has an annual budget of around €150,000. The largest part, for nearly €120,000 euros per year, is provided by contract between the ecomuseum and Municipality of Argenta, which is particularly directed to the payment of salaries to the employees of the structure. Even the rest of the funding is, for the most part, from public sources, but it is worth highlighting that the ecomuseum’s staff presents a particular to access to various funding lines on different public projects, partly regional, partly national, and partly from the EU.

With reference to management tools, there is a poor presence. This mainly depends on the circumstance that the ecomuseum is not autonomous from a management point of view but is comparable with an organizational unit of the Argenta municipality. However, the development of autonomous management tools compatible with this governance system, such as performance measurement systems or forms of non-financial reporting, has not been implemented due to the lack of specific economic–managerial skills and the scarcity of financial resources that can be specifically dedicated to these projects.

Ecomuseum of Bagnacavallo

The Ecomuseum of Bagnacavallo, also known as the Ecomuseum of Marsh Herbs, owes its foundation to the activity carried out by the Cultural Association “Civiltà Erbe Palustri” (Marsh Herbs Civilization). In June 1985, the founding nucleus of the future association began its activities. A young married couple, composed by Luigi Barangani and Maria Rosa Bagnari—who was the director of the ecomuseum for years—interested in recovering the artisan art that had once characterized the economy of their territory was the propulsive heart of this first nucleus. Thus began the first survey work within the country to recover original equipment, bundles of grass, artifacts, and leftovers to create a small exhibition. At the same time, the supporters of the initiative tried to identify people who still possessed the unaltered technical background of the manual arts in the use of marsh grasses and were available to collaborate on the first informal idea of the reconstruction of classical production for the purpose of study and collection. As the first result of the research was carried out, the first edition of the Exhibition of the Marsh Herbs Civilization was held, with the first group of expert craftsmen at work, arousing great emotion throughout the community. With this initiative, the history of this ecomuseum began.

However, the history of the ecomuseum was born much earlier. In 1971, after Maria Rosa had married Luigi, when the young couple moved into their new home, Maria Rosa expressed the desire to beautify the small apartment with the window curtains that she had noticed in tatters in the bordering large house, previously Luigi’s aunt’s workshop. In this way, Maria Rosa, thanks to the teachings of her mother-in-law, learned to build curtains for windows using marsh grasses and rushes from the valley as per local tradition. The curtains displayed on the windows overlooking the main street began to attract attention for their beauty and originality to the point that several passers commissioned them.

Thanks to this origin, the Ecomuseum of Marsh Herbs has been characterized since its inception as a participatory project carried out by the people, by the population—first and foremost that of Villanova (a fraction of the Municipality of Bagnacavallo with 4,000 inhabitants). The sense of participation, which has always characterized the history of the ecomuseum, can be summarized in two phases.

The first phase can be considered the start of the ecomuseum story, which has not yet been defined in this way; it was aimed at making the community aware of itself and of its own history, culture, and tradition to avoid the loss of identity. The research and recovery of tradition was carried out among the people, with their help and active contribution to rediscovering and restoring a unique cultural heritage based on the values of aesthetics, a sustainable economy, and solidarity between generations. Reviving the processing of marsh grasses house by house, the grass once again invaded the country, causing amazement and emotion in the population and great interest in the institutions themselves. The completion of this first phase, therefore, led to the establishment of the ecomuseum in name and in fact.

The second participatory phase arose from the awareness that the importance of safeguarding the specificity and uniqueness of the recovered subject forced it to be disseminated and transmitted outside the limited boundaries of the municipality of Bagnacavallo, and even more than a fraction of it, such as Villanova. The logical thread that connected the history of the ecomuseum to the world of the valley and to the lands of the manual arts was the Lamone River, which has become a new horizon of interest. Thus, a new project was born: Lamone Bene Comune (LBC), literally “Lamone as a common good.” It was founded with the following objectives:

- To stimulate the participation of all the communities located along the Lamone River toward a single cultural horizon

- To raise awareness of territorial education for sustainability

- To enhance and promote the area around the river

- To safeguard the landscape and biodiversity of the lands and valleys of the Lamone

Currently, the collections acquired so far exceed 2,500 objects, which can be described as weaving products, textures, and artifacts made with wild herbs supplied by the nearby valley environment and by the various processing of soft woods.

The actions and products created by the ecomuseum are continuous negotiation tables, recovery of tradition (e.g., fires in March at the same time along the whole river, propitiatory crosses in the countryside, and potato crib with playing cards), creation of a vegetable garden of flowers, and forgotten smells.

The ecomuseum also promotes environmental protection issues, starting with the LBC project, which provides for the recovery and maintenance of the left embankment top of the Lamone River and its two continuations, one toward the sea and the other toward the hill, taking care of problems relating to the hydrogeological instability of Punta Alberete with the salinization processes that are advancing throughout the territory. The community development objectives are evident: the ecomuseum is aimed primarily at the local community, and it has the objective of stimulating community participation to promote the re-appropriation of the prior culture through projects of solidarity between generations. Finally, for both residents and tourists, there is a desire to raise awareness of territorial education in sustainability, safeguarding the landscape and biodiversity of the lands and valleys of the Lamone. In short, healthy use of the territory is promoted, even through responsible and sustainable tourism. In this, even the rediscovery of traditional cuisine linked to the territory, based on the conscious use of resources, is at the center of a rich activity of cooking workshops open to all.

From a tourist point of view, indeed, the promotion of responsible and sustainable tourism proposals involves tourists with alternative routes—compared to the traditional tourism of Romagna—based on the concept of slow tourism, exploiting already existing routes that connect the country’s roads to embankment paths. In this context, the ecomuseum attracts interest above all of the cycle tourists, whose tourist activity particularly lends itself to lingering on the activities and itineraries proposed by the ecomuseum.

As in the previously analyzed case, the pandemic, which, in any case, implied the closure of the office in one of the most acute periods in 2021, has not blocked the activities. During the closing period, rich laboratory activity was carried out online. These projects were also brought back into attendance as soon as the rules allowed. In 2021, a summer school was also promoted entitled “Summer School of the Ancient Arts. Solidarity between generations so as not to lose wisdom and a sustainable economy.” This title is emblematic of the aim still pursued by the ecomuseum, which makes use of a rich collaboration with the local associative fabric beyond the driving role of the association that manages it.

From a governance point of view, the ecomuseum is a cultural institute of the Municipality of Bagnacavallo, depending on the Direction of the Civic Museums of Bagnacavallo, and is managed by the founding body, the private association Civiltà Erbe Palustri. The municipality plays the role of orientation, direction, and control of the activities carried out by the ecomuseum in view of the tourist impact on the area. The association covers its managerial autonomy in organizing festivals, markets, environmental education projects, temporary installations, and the collection of evidence of the material culture of the local community.

Thanks to the attention of the public entity, there has always been collaboration with a public–private partnership for the use of public spaces. As already seen, the municipality has been interested in this activity since its beginning. The ecomuseum, between volunteers and collaborators, involves about 50 people, although these activities constitute their job only for the director and another collaborator.

The annual budget of the Cultural Association Civiltà Erbe Palustri is around 70,000–80,000 euros. This budget is sometimes supplemented by municipal public contributions, as well as by expenditure items of the municipality that affect interventions in the territory, even in the areas where the activity of the ecomuseum takes place. Often, public funds derived from competitive tenders, European and regional, have been intercepted for specific activities. Their own sources of revenue concern the museum store with ethnic artifacts from Romagna, a part coming from ticket office entrances and fees for the use of the convivial room for events and itinerant workshops linked to museum activity.

Despite the development of a set of activities fully consistent with the ecomuseum mission and its breadth, this second ecomuseum also does not have adequate development of management tools. This circumstance is also due to the lack of specific skills in the field of business administration within the association, even if the element that seems to emerge is also that their usefulness or necessity is not always perceived, with the potential detriment of even more incisive paths of growth and development of the ecomuseum.

Ecomuseum of hill and wine of Castello di Serravalle

The Ecomuseum of Hill and Wine has been running since May 2004. It was born with the aim of protecting and enhancing the cultural and natural heritage of Castello di Serravalle, a town belonging to the Municipality of Valsamoggia, inserted into the hilly landscape of the province of Bologna. The focus of this ecomuseum is on evidence of centuries-old human use of the land and the important buildings that express the relationship between landscape and man.

The owner of the venue and of the exhibitions is the Municipality of Valsamoggia, which comes from the merger of the municipalities of Castello di Serravalle (the owner entity of the Ecomuseum at its birth) with those of Bazzano, Crespellano, Monteveglio, and Savigno, which are all located in the territory of the province (here named the “metropolitan city”) of Bologna. The ecomuseum management has been entrusted to the public trust Foundation “Rocca dei Bentivoglio.” This foundation is under the direct control of the Municipality of Valsamoggia and manages the ecomuseum through a system of in-house provision. Some functional and operational tasks for the management of the ecomuseum are assigned to the non-profit cultural association “Terre di Jacopino,” whose associates participate in the management of the ecomuseum on a voluntary basis.

The ecomuseum has a main exhibition venue at a building called “Captain’s House,” which was built in 1,235 by Jacopino from San Lorenzo in Collina within the fortified village of Castello di Serravalle. The ecomuseum comprises nine systems of routes, which are the main themes of the relationship between man and land. Visitors can find educational panels for each system at the main exhibition venue with detailed text and images and symbolic objects with evocative aims: summary information and an essential exposure aim to bring the visitor outside in contact with the real aspects of the territory.

The ecomuseum proposes specific museum itineraries to its visitors focused on “nature and landscape: the gullies”; “architecture and land: the castle of Serravalle”; “man and landscape: work in the fields”; “humans and animals: zootechnics”; “the vine, the wine, and the landscape”; “the territory and its inhabitants: the first censuses”; “the post-war period and the reorganization of the territory”; “culture and folk tradition: folklore”; and “archeology and territory.”

In addition to the panels and objects for the nine itineraries, in the main exhibition venue of the ecomuseum, there is a room with archaeological findings of a Roman villa of the imperial age located just downstream of the fortified village. The most interesting artifact is a large terracotta that could hold more than 1,000 L of wine and inspire some local producers, such as the ancient Romans, to revive the wine in amphorae. In addition to educational programs for kindergartens and primary and secondary schools, the ecomuseum offers guided tours and tastings by appointment.

In recent years, the activity of the ecomuseum outside the main exhibition venue has been further developed, thanks to the support of the “Pro loco” (local tourism promotion association) of Castello di Serravalle. In fact, walks and excursions have been conceived to intertwine the places of the ecomuseum and the related themes. Paths regarding the German refuges in the area thus emerged, with walks in the various refuges, projects from which other enhancement projects were born, such as the walk on the occasion of the festival on the ancient vines or the walk to the ancient sources. This has helped bring these issues, even outside Castello di Serravalle, to nearby territories. In short, there has been work aimed primarily at establishing a dialogue between the communities that form part of the rather extensive territory of the Municipality of Valsamoggia. This also appeared to be useful in overcoming the problems derived from the merger of the municipalities, which did not make everyone happy. Using the historical-cultural and landscape contents of continuity that exist between the territories has allowed for greater understanding and rapprochement.

The primary goal of the ecomuseum is to become a tool for the development of a form of culturally sustainable tourism in the territory. Some of the results have already been achieved, considering that after the birth of the ecomuseum, an economic appreciation of the buildings in the local area was observed in testimony to the revitalization of the area for tourism. Another important aim of the ecomuseum is the involvement of the population in creating a sense of awareness about the values of the territory. In particular, the engagement initiatives have been addressed to two specific targets: the segments of the older population and the younger population. For the elderly, initiatives were put in place with the aim of preserving the memory and the typical know-how of the rural world. To young people, instead, activities were promoted aimed at knowledge of their territory and the importance of taking care of it.

In agreement with these objectives, there have been meetings at the community center for the elderly and classes at the junior high school in the local area on the ancient crafts and the cycle of Parmesan cheese. There were three exhibitions to engage citizens with local origins, with the use of pictures taken from family albums and provided directly by the citizens themselves.

Other activities organized by the ecomuseum are addressed to the conservation of the peasant theatrical culture and to the use of dialect, supporting and disseminating performances of a recreational spontaneous group that animates the local carnivals and makes representations in dialect, especially staging “La Flepa,” a comic opera written by Giulio Cesare Croce, which has been orally transmitted for over three centuries and was reconstructed 20 years ago from the fragments that the elders of the valley recited by heart.

The COVID-19 pandemic was a crucial moment in this ecomuseum. In fact, before the pandemic, most of the operational activities were carried out by the historical staff of the “Terre di Jacopino” Association, whose average age was quite high. For this reason, since, as is known, the elderly people were those most at risk during the pandemic period, there was a need for the “Rocca dei Bentivoglio” Foundation to identify new initiatives and new activities that could be promoted in an alternative way by the ecomuseum compared to those traditionally promoted. This has led to the greater involvement of other local associations and the development of new online activities. Therefore, this represented, in a certain sense, a concrete way of implementing the aim that the ecomuseum itself had in its intentions: promoting intergenerational dialogue and favoring greater collaboration between the “historical” volunteers of the ecomuseum and the new resources activated by the foundation.

From the point of view of financial management, the annual budget available is approximately 10,000 euros. Although this budget is significantly lower than one of the above-presented cases, it appears interesting to note how, from the point of view of the percentage distribution of resources, this ecomuseum has a good degree of self-financing. In fact, the municipality contributes only about 30% of the budget, incurring the costs of managing the main exhibition venue and its offices. The remainder of the budget is covered by revenues raised by the association. They come for about another 30% from themed events in the village, 20% from the organization of tours, and 20% from sales of local products.

Similar to what was found in the other cases, this ecomuseum does not present the use of specific managerial tools. The small size of this reality leads to not detecting the usefulness or need for these tools, in addition to the fact that there is a lack of human and financial resources capable of implementing them.

Discussion

The aim of this section is to analyze what has emerged from the case studies, responding to the two research questions, which were about the kind of ecomuseum development strategies, and the management tools adopted to increase their effectiveness.

With reference to the first profile, the three cases were different, demonstrating variety and complexity that characterize the ecomuseums, even worldwide, but with relevant common features. The common elements mainly concern, on the one hand, the genesis, development, and participatory actions, which are implemented in all cases, and, on the other hand, the presence of a political will that is a decisive and stabilizing factor for the ecomuseum. Furthermore, it should be noted that the investigated development strategies properly mirror the main ongoing EU policies. On the one hand, cultural and natural heritage are envisaged as a shared resource, raising awareness of common history and values and reinforcing a sense of belonging to a common cultural and political space consistent with the 2019 European framework for action on cultural heritage based on the European Year of Cultural Heritage 2018 (European Commission, 2019). On the other hand, the analyzed cases put cultural and natural heritage at the heart of broader public policies consistently with the vision of the role of culture and cultural heritage in the European green deal (European Commission, 2022).

The divergent aspects relate to different management structures, different purposes, and different operating ways of realizing the activities, mainly attributable to the specificities of the territories. The different expressions of the development strategies of these three ecomuseums are not seen as conflicting. In fact, all three cases demonstrate specific attention to sustainable tourism projects, which have an impact on the cultural side of belonging and knowledge of the area and its heritage. Therefore, the perspectives of sustainable tourism promotion and community involvement are present in all cases analyzed.

In all the cases, the ecomuseum project seems, however, to overlap this perspective in order to embrace a wider perspective of the “cultural district.” In the examined cases, the territorial element is, first, the common ground between the industrial district and the cultural district. The goal of a cultural district is to be a product of a particular territory based on territorial integration of the cultural offer. Specifically, the cultural district, on the one hand, implements a process of enhancing cultural resources of different types and, on the other hand, connects this process with the system of professions, services, and infrastructure connected with the same enhancement activities. According to this perspective, the process of developing cultural resources in the form of a district can have positive consequences in terms of employment, entrepreneurship, and innovation in various sectors.

In this context, an ecomuseum is part of a cultural district that is able to integrate with this productive and industrial system in the territory. These aspects seem to be present, as previously said, even with different degrees of relevance in the three cases analyzed.

A further expansion of the ecomuseum mission development seems to be present. In this case, a holistic approach to the sociocultural development of the local area is emerging (Badia and Deodato, 2015): the promotion of tourism in itself is beyond the scope of the ecomuseum, and even the development of entrepreneurship does not appear as central or primary factors. The ecomuseum task is primarily to improve the perceived quality of the territory, first from its residents. This can help to promote social development, and possibly economic growth, as well as—but not only—through sustainable tourism initiatives. A thorough knowledge and understanding of the natural and man-made components of the territory are the first fundamental elements of this perspective. Such knowledge and understanding, however, are only possible with the real involvement of the community—to be achieved both by local knowledge development initiatives at the local population and through its involvement with participatory tools. For these reasons, the cases of Argenta and Bagnacavallo seem to be further along this path, whereas Castello di Serravalle is trying to start it.

The holistic approach to the sociocultural development of the local area can strengthen the community feeling that is the basis of every ecomuseum project. With its different ingredients, this perspective attempts to root a sense of responsibility and awareness of an area that becomes a place of culture and potentially socioeconomic development. After all, the goal of the ecomuseum is to improve the quality of life of the local community; the first step in this process should consist precisely of an awareness of the quality aspects of the territory, with its strengths and its critical issues, through an integrated and holistic perspective.

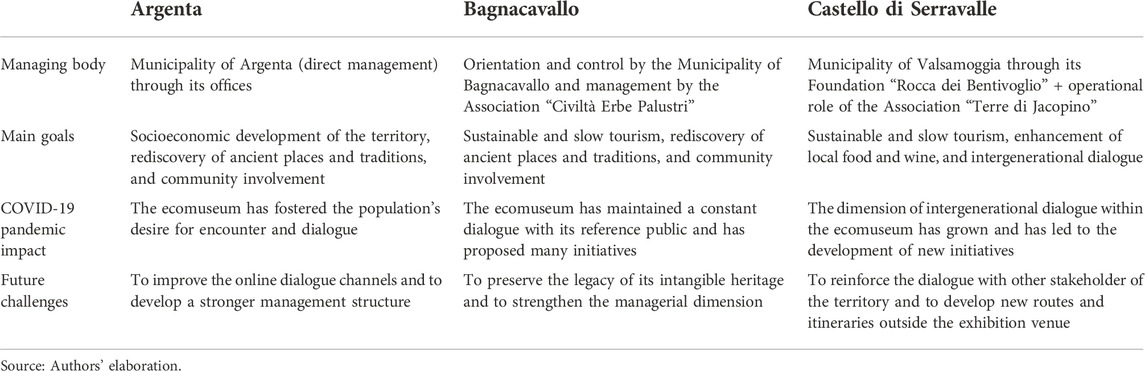

The following Table 1 synthesized the most relevant aspects emerging from the previous analysis and allows for a possible comparison among the three ecomuseums. In particular, the last line—about possible future challenges—contains some possible issues of development for the three institutions, which are the results of the authors’ perceptions after the conclusion of the case studies.

Another point of interest emerges from the comparison of the impacts that the COVID-19 pandemic had on the three ecomuseums. For all the cases analyzed, although the pandemic remains an event that has had a tragic impact on communities, from the point of view of ecomuseum management, it has been able to activate proactive response paths that have allowed certain improvements in management, especially based on the use of new technologies, both in dialogue with the community and between internal stakeholders.

With reference to the second profile, the role of the management tools, the cases present similar results (i.e., this kind of instrument is very little used). Fundamentally, three orders of motivation are behind this circumstance:

- Lack of skills

- Insufficient resources (financial and human)

- Incomplete perception of the usefulness or need for such tools

The first motivation is actually a problem, which often emerges in the context of museum studies and is present mainly in the cases of Argenta and Bagnacavallo. The second motivation represents an evident problem in organizational structures of a few dimensions, and it has emerged from the cases of Argenta and Castello di Serravalle. Finally, the third order of motivation can lead to problems when management is unable to understand the importance of these tools for the stronger development of its structure. As proposed by some academic literature, a possible solution to these problems relates to overcoming the dimensional limits of the governance structures of these ecomuseum realities. The problem of the size of the ecomuseums and their funding systems requires further development. The problem with the size scale concerns cultural institutions in general (Donato, 2013). The ecomuseum, by its nature, cannot be separated from being rooted in small realities characterized by low population density and difficult access to financial resources. Overcoming the reduced scale of ecomuseums would mean, in some cases, overcoming the proper meaning of the ecomuseum; therefore, this is not the correct way to go through. A correct solution in this regard would appear instead to develop (and in the experience of the Ecomuseum of Argenta is interesting) a system of networking and institutional partnerships with other ecomuseums or similar situations that would allow the increase of the critical mass and the political weight of the ecomuseum without distorting its original meaning. This idea is fully consistent with the studies that proposed a multilevel governance perspective for the management of cultural heritage (Bonet and Donato, 2011). A possible further development of these ideas could consist of analyzing the opportunities for full adoption of a perspective of collaborative governance in the ecomuseum context (Jeon and Kim, 2021).

Conclusion

Starting from the considerations set out in the previous section, this concluding section intends to carry out an analysis of the possibilities for the future development of this research, starting from the key concept that the proposed study was exploratory (i.e., aimed at validating the possibility of expanding the hypotheses here formulated in different contexts). First, the research was able to highlight only that in the cases, there was a scarce presence, or even the absence, of appropriate managerial tools suitable for supporting the development of ecomuseum strategies. The development of this study in new contexts of analysis could start from the observation of ecomuseum realities, if existing, in which such tools, such as performance measurement systems or non-financial reporting systems, have been developed.

Regarding this last aspect, the role of non-financial reporting, it primarily represents an accountability tool that appears to be particularly appropriated in an ecomuseum context, as suggested in previous works (Magliacani, 2015). A full involvement of the community is represented not only by citizen adhesion to the activities proposed by the ecomuseum, but it is also fully realized when some form of transparent communication to the community of the activities carried out—and related to the use of public financial resources—is provided.

A further point for future research can be represented by the role played by the COVID-19 pandemic with reference to the topics developed in this work. Some authors have already produced preliminary studies that have highlighted how ecomuseums played a key role in supporting local communities in certain contexts, precisely during the pandemic period (Santo et al., 2021). These considerations seem to deserve further study, not only with a perspective aimed at what happened in the past but also to understand what lessons the pandemic period has produced in the ecomuseum sector, with reference to the ability of ecomuseums to know how to interpret and deal with moments of unexpected crisis.

In conclusion, this work also has some limitations. First, it considered a single geographical context (Emilia Romagna Region, Italy), so the results could be influenced by the specificities of the identified territorial context. Second, the work has considered only the perspective of the ecomuseum managers, but a potential development of the research could consider the point of view of the people involved in the ecomuseum activities.

Author's note

This work is a new and revised version of: Badia Francesco, Deodato Giuditta, (2015), Strategic Profiles of Ecomuseum Management and Community Involvement in Italy, presented at the 6th Research Session of the 23rd Encatc Annual Conference “The Ecology of Culture: Community Engagement, Co-creation, Cross Fertilization,” held in Lecce, 21–23 October 2015, and published into the Conference Proceedings with ISBN code 9789299003626, pp. 31–46.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

Conducted experiments: FB; participated in research conception and design: FB and FD; wrote and drafted the manuscript: FB; critical revision of the article: FB and FD; performed data analysis: FB; contributed to writing the manuscript: FB and FD. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors express their sincere thanks to Nerina Baldi and Benedetta Bolognesi of the Ecomuseum of Argenta, Maria Rosa Bagnari of the Ecomuseum of Bagnacavallo, Luigi Vezzalini and Rita Nobili of the Ecomuseum of Castello di Serravalle, and the colleagues Barbara Caravita and Giuditta Deodato for the relevant suggestions and ideas provided regarding research and practice in the ecomuseum field. The contributions provided by all the subjects cited here were a source of inspiration for this work.

References

Arnaboldi, M., and Spiller, N. (2011). Actor-network theory and stakeholder collaboration: the case of cultural districts. Tour. Manag. 32 (3), 641–654. doi:10.1016/j.tourman.2010.05.016

Badia, F., and Deodato, G. (2015). “Strategic profiles of ecomuseum management and community involvement in Italy,” in ENCATC, The Ecology of Culture: Community Engagement, Co-creation, Cross Fertilization, Book Proceedings, 6th Annual Research Session, Bruxelles: Encatc, October 21-23 2015, 31–46.

Becattini, G. (2004). Industrial districts: a new approach to industrial change. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

Belliggiano, A., Bindi, L., and Ievoli, C. (2021). Walking along the sheeptrack rural tourism, ecomuseums, and bio-cultural heritage. Sustainability 13 (16), 8870–8922. doi:10.3390/su13168870

Bindi, L., Conti, M., and Belliggiano, A. (2022). Sense of place, biocultural heritage, and sustainable knowledge and practices in three Italian rural regeneration processes. Sustainability 14 (8), 4858–4923. doi:10.3390/su14084858

Bonet, L., and Donato, F. (2011). The financial crisis and its impact on the current models of governance and management of the cultural sector in Europe. Eur. J. Cult. Manag. Policy 1 (1), 4–11. doi:10.3389/ejcmp.2023.v1iss1-article-1

Bowers, J. (2016). Developing sustainable tourism through ecomuseology: a case study in the Rupununi region of Guyana. J. Sustain. Tour. 24 (5), 758–782. doi:10.1080/09669582.2015.1085867

Choi, M. S. (2017). A new model in an old village: the challenges of developing an ecomuseum. Mus. Int. 69 (1-2), 68–79. doi:10.1111/muse.12151

Clifford, S., and King, A. (1996). From place to place. Maps and parish maps. London: Common Ground.

Cogo, M. (2006). “Ecomuseums of the autonomous provincial authority of Trento, Italy,” in Communication and exploration: papers of the international ecomuseum forum, Guihzou, China. Editors D. Su, P. Davis, M. Maggi, and J. Zhang (Guiyang: Chinese Society of Museums), 95–102.

Corral, Ó. N. (2019). Ecomuseums in Spain: an analysis of their characteristics and typologies. Muzeologia a Kult. Dedicstvo 7 (1), 7–26.

Corsane, G., Davis, P., Elliott, S., Maggi, M., Murtas, D., and Rogers, S. (2007). Ecomuseum evaluation: experiences in Piemonte and Liguria, Italy. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 13 (2), 101–116. doi:10.1080/13527250601118936

COUNCIL OF EUROPE (2005). Council of Europe framework convention on the value of cultural heritage for society. United Kingdom: Cardiff EDC. doi:10.18356/5713874d-en-fr

Davis, P. (2008). “New museologies and the ecomuseum,” in The routledge research companion to heritage and identity. Editors P. Howard,, and B. Graham (London: Routledge), 397–414.

De Varine, H. (2002). Les racines du futur: le patrimoine au service du développement local. Chalon sur Saône: ASDIC.

De Varine, H. (2006). “Ecomuseology and sustainable development,” in Communication and exploration: papers of the international ecomuseum forum, Guihzou, China. Editors D. Su, P. Davis, M. Maggi, and J. Zhang (Guiyang: Chinese Society of Museums), 59–62.

Doğan, M. (2019). The ecomuseum and solidarity tourism: a case study from northeast Turkey. J. Cult. Herit. Manag. Sustain. Dev. 9 (4), 537–552. doi:10.1108/jchmsd-12-2017-0086

Donato, F. (2013). La crisi sprecata. Per una riforma dei modelli di governance e di management del patrimonio culturale italiano. Roma: Aracne.

Ducros, H. B. (2017). Confronting sustainable development in two rural heritage valorization models. J. Sustain. Tour. 25 (3), 327–343. doi:10.1080/09669582.2016.1206552

Eisenhardt, K. M., and Graebner, M. E. (2007). Theory building from cases: opportunities and challenges. Acad. Manag. J. 50 (1), 25–32. doi:10.5465/amj.2007.24160888

EUROPEAN COMMISSION, Directorate-general for education, youth, sport and culture (2019). European framework for action on cultural heritage. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union.

EUROPEAN COMMISSION, Directorate-general for education, youth, sport and culture (2022), strengthening cultural heritage resilience for climate change. Where the European Green Deal meets cultural heritage. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union.

Guaran, A., and Michelutti, E. (2021). Landscape as ‘working field’ for territorial identity in Friuli Venezia Giulia ecomuseums action. Geoj. Libr. 127, 81–94. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-66766-5_6

Gugu, S., and Dal Molin, M. (2016). Collaborative local cultural governance: what works? The case of cultural districts in Italy. Adm. Soc. 48 (2), 237–262. doi:10.1177/0095399715581037

Howard, P. (2002). The eco-museum: innovation that risks the future. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 8 (1), 63–72. doi:10.1080/13527250220119947

Hunter, C. (1997). Sustainable tourism as an adaptive paradigm. Ann. Tour. Res. 24 (4), 850–867. doi:10.1016/s0160-7383(97)00036-4

Jeon, J., and Kim, H. (2021). Leading collaborative governance in the cultural sector: the participatory cases of Korean arts organizations. Int. J. Arts Manag. 24 (1), 63–74.

Liu, Z.-H., and Lee, Y.-J. (2015). A method for development of ecomuseums in Taiwan. Sustainability 7 (10), 13249–13269. doi:10.3390/su71013249

Maggi, M. (2006). “Ecomuseums worldwide: converging routes among similar obstacles,” in Communication and exploration: Papers of the international ecomuseum forum, Guihzou, China. Editors D. Su, P. Davis, M. Maggi, and J. Zhang (Guiyang: Chinese Society of Museums), 63–67.

Magliacani, M. (2015). Managing cultural heritage: ecomuseum, community governance and social accountability. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Pappalardo, G. (2020). Community-based processes for revitalizing heritage: questioning justice in the experimental practice of ecomuseums. Sustainability 12 (21), 9270–9318. doi:10.3390/su12219270

Parker, B. (2006). Constructing community through maps? Power and praxis in community mapping. Prof. Geogr. 58 (4), 470–484. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9272.2006.00583.x

Qu, S. Q., and Dumay, J. (2011). The qualitative research interview. Qual. Res. Account. Manag. 8 (3), 238–264. doi:10.1108/11766091111162070

Riviere, G. H. (1985). The ecomuseum: an evolutive definition. Mus. Int. 37 (4), 182–183. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0033.1985.tb00581.x

Sacco, P. L., Ferilli, G., Blessi, G. T., and Nuccio, M. (2013). Culture as an engine of local development processes: system-wide cultural districts I: theory. Growth Change 44 (4), 555–570. doi:10.1111/grow.12020

Santagata, W. (2002). Cultural districts, property rights and sustainable economic growth. Int. J. Urban Regional Res. 26 (1), 9–23. doi:10.1111/1468-2427.00360

Santo, R. D., Baldi, N., Duca, A. D., and Rossi, A. (2017). The strategic manifesto of Italian ecomuseums. Mus. Int. 69 (1-2), 86–95. doi:10.1111/muse.12153

Santo, R. D., Almeida, N. H. O., and Riva, R. (2021). Distant but united: a cooperation charter between ecomuseums of Italy and Brazil. Mus. International¸ 73 (3-4), 54–67. doi:10.1080/13500775.2021.2016278

Schieb-Bienfait, N., Saives, A.-L., Charles-Pauvers, B., Emin, S., and Morteau, H. (2018). Grouping or grounding? Cultural district and creative cluster management in Nantes, France. Int. J. Arts Manag. 20 (2), 71–84.

Simeoni, F., and De Crescenzo, V. (2018). Ecomuseums (on clean energy), cycle tourism and civic crowdfunding: a new match for sustainability? Sustainability 10 (3), 817–916. doi:10.3390/su10030817

Sokka, S., Badia, F., Kangas, A., and Donato, F. (2021). Governance of cultural heritage: towards participatory approaches. Eur. J. Cult. Manag. Policy 11 (1), 4–19. doi:10.3389/ejcmp.2023.v11iss1-article-1

Sutter, G. C., Sperlich, T., Worts, D., Rivard, R., and Teather, L. (2016). Fostering cultures of sustainability through community-engaged museums: the history and re-emergence of ecomuseums in Canada and the USA. Sustainability 8 (12), 1310–1319. doi:10.3390/su8121310

Tsipra, T., and Drinia, H. (2022). Geocultural landscape and sustainable development at Apano Meria in Syros island, central Aegean Sea, Greece: an ecomuseological approach for the promotion of geological heritage. Heritage 5 (3), 2160–2180. doi:10.3390/heritage5030113

UNESCO (2002). The Budapest declaration on world heritage. France: UNESCO World Heritage Centre. doi:10.1080/00293650903354262

Wuisang, C. E. V., Rengkung, J., and Rondonuwu, D. M. (2018). Towards sustainable cultural landscape: a challenge in developing ecomuseum in Minahasa region. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 179 (1), 012017–012019. doi:10.1088/1755-1315/179/1/012017

Keywords: museum management, cultural heritage, sustainability, community involvement, COVID-19 pandemic

Citation: Badia F and Donato F (2023) Management perspectives for ecomuseums effectiveness: a holistic approach to sociocultural development of local areas. Eur. J. Cult. Manag. Polic. 13:11851. doi: 10.3389/ejcmp.2023.11851

Received: 03 December 2022; Accepted: 07 July 2023;

Published: 26 October 2023.

Copyright © 2023 Badia and Donato. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Francesco Badia, ZnJhbmNlc2NvLmJhZGlhQGhvdG1haWwuY29t

†Deceased

Francesco Badia

Francesco Badia Fabio Donato

Fabio Donato