Abstract

Cultural policies of the past decades in Europe and especially in France, have placed the objective of diversity at the heart of their field of action. However, no cultural diversity indicator is published, which would make it possible to evaluate the results of a policy in favour of diversity in audiovisual or music industries. However, we find in the scientific literature works that provide such measurement indicators. This article details the construction of these indicators and shows how they could be usefully mobilised in the service of new regulations in favour of cultural diversity on cultural online services.

Introduction

Since 1989, the “Television Without Frontiers” directive, intended to promote the circulation of audiovisual works within Europe, simultaneously strengthens the legitimacy of national broadcasting quota policies against countries outside Europe from a protectionist perspective. The objective was to act as “a means of promoting production, independent production and distribution” in the audiovisual industry. The revised version of the Television Without Frontiers adopted by the Council of Europe in 2007 cites the “preservation of cultural diversity” as one of its main objectives, while being absent from the original.1 In a broader context, the 117 member countries of GATT—ancestor of the WTO—adopted, with difficulty, in 1994 a compromise on the audiovisual issue, which over the years had become a major point of opposition between Europe, France in particular, and the United States. At the end of this compromise, the audiovisual sector was not excluded from the field of international negotiations, but the Europeans obtained the “Cultural exception” that is to say not to make a commitment to liberalisation in this sector and to preserve their support and quota mechanisms.

At the end of the 1990s, without explicitly claiming it, the European Commission gradually abandoned, in official speeches and reports, the term “cultural exception,” with defensive and protectionist connotations, in favour of the concept of “Cultural Diversity,” and will try to reconcile industrial and cultural objectives. For example, in 1998 came a report from the European Commission’s High-Level Group on Audiovisual Policy. This report, entitled “The Digital Age: European Audiovisual Policy,” in a protectionist view, highlights the potential threat of market fragmentation brought on by an increase in the number of television channels and warns that it will become more difficult for “European producers to compete with American imports.” At the same time, it says that “Europe must maintain its cultural and linguistic diversity and uphold its core values also in the digital age” and that “there are tremendous opportunities opening up and Europe must seize them or others will simply do so in our place.” In its Communication on the Future of European Regulatory Audiovisual Policy, the European Commission stresses that “regulatory policy in the sector has to safeguard certain public interests,” and cultural diversity tops the list.2

Finally, the revised version of the EU’s AVMS directive of 2010 adopted in November 2018 makes a direct link between the promotion of European works and the promotion of cultural diversity: “[on-demand audiovisual media services] should, where practicable, promote the production and distribution of European works and thus contribute actively to the promotion of cultural diversity”.3 The concept of cultural diversity has therefore been translated into European regulation policies. Additionally, the political ambition to promote cultural diversity to some extent serves to justify applying established regulatory practices to new markets (such as on-demand audiovisual services).

Cultural diversity has therefore become an object of particular attention of many political leaders in Europe and especially in France, and an essential objective of any cultural policy. Although cultural diversity is a political goal, it remains an unclear terminology and struggles to receive elements of objectification that could give rise to an evaluation. Similar to all public policies, those in favour of the diversity of cultural content4 should indeed be able to be evaluated. For this, whether experimental (or quasi-experimental) methods, or other impact evaluation methods, several steps are necessary: identifying objectives, implementing the means to achieve them and finally, setting up indicators to measure the results of the policy obtained in relation to the stated objectives (Nicolas and Gergaud, 2016).

Measurement indicators are therefore essential to any process of regulation, and to the evaluation of this regulation. Public policies concerning unemployment, inflation, taxation, etc., in order to understand the results of the means implemented, are based on indicators (inflation rate, unemployment rate, compulsory deduction rate…), which are certainly imperfect, questionable and disputed, but nevertheless are available.

There is nothing like this when it comes to cultural diversity policies. In France, since the creation of the Ministry in charge of Cultural Affairs in 1959, diversity is however, with democratisation, always considered as one of the two main objectives of cultural policies, in order to struggle against the possible supply standardisation (Poirrier, 2016). Multiple performance indicators are displayed by public authorities, sometimes very specific and not very macroeconomic: the integration rate of graduates from cultural education, attendance at subsidised places, the proportion of children having received an artistic education, etc.5 However, nothing appears on diversity. No “diversity rate” is published which would allow comparisons to be made between countries, or to follow the evolution of this indicator over time. Facing the absence of clear reference indicators, how can we judge whether a policy is a success or a failure? How to verify that a quota policy, for example, really has the effect of improving cultural diversity?

However, indicators for measuring cultural diversity could exist. The ambition of this article is to detail the construction of these indicators and to show how they could be subject to appropriation by public authorities in Europe, to carry out policies in favour of cultural diversity in both audiovisual and music sectors. The mobilisation of these indicators could indeed facilitate the implementation of new forms of regulation adapted to a delinearised world. We find in the scientific literature works which, with different methodologies, provide indicators for measuring cultural diversity. After presenting these works (Measuring cultural diversity: the contribution of academic works section), we identify the three steps which from a normative point of view, seem to be essential to us for the construction of measurement indicators (Building diversity measurement indicators: a three-step approach section). The rise of recommendation systems calls for adapting this approach to online cultural services (The central role of recommendation for cultural diversity section). Finally, we specify how the available indicators can be used to support new regulations in favour of cultural diversity (Mobilising available indicators to serve a new regulation of cultural diversity section).

Measuring cultural diversity: the contribution of academic works

In the socio-economics literature on measurement issues of cultural diversity in cinema, audiovisual, recorded music and books, we have found around twenty articles available in French and English. These papers allow us to build a framework of analysis about how cultural diversity has been previously addressed. Even if the methodological choices, although decisive, are not always discussed or made explicit, Table 1 details the methodologies adopted and constitutes an attempt to make them comparable within the same framework of analysis.

TABLE 1

| Publication | Sample | Criteria | Measurement tools by dimension |

|---|---|---|---|

| Live performance industry | |||

| Pietrzyk (2017) | Offer of shows in each hall of a panel of 93 large halls in France. Demand is illustrated by box office receipts from the same venues | Shows, production structures, genres of show | Variety: Number of occurrences of each category. Balance: Percentage shares of each category |

| Publishing industry | |||

| Donnat (2018) | Demand for books illustrated by sales from GFK databases between 2007 and 2016 | Titles, authors, literary genre, publishers | Variety: Number of occurrences of each category. Balance: Percentage shares of each category. Disparity: Proportion of new entrants in the sample |

| Benhamou and Peltier (2007) | Supply of books published between 1990 and 2003. Demand for books is illustrated by the sales figures for each book considered in the supply | Titles, languages, literary genres, authors, nationality of the work | Variety: Number of occurrences of each category. Balance: Percentage shares of each category, Herfindahl-Hirschman concentration index. Disparity: Linguistic distances |

| Recorded music industry | |||

| ARCOM (2022) | Listener demand, illustrated by the top 100 most listened songs per week on three online services, between November 2017 and January 2020. Also illustrated by the Top 200 most listened-to songs on radio per week, between November 2017 and January 2020 | Languages of expression, musical aesthetics, distributors, titles, artists | Variety: Number of occurrences of each category. Balance: Percentage shares of each category, Herfindahl-Hirschman concentration index |

| Bourreau et al. (2022) | Demand from listeners, illustrated by the Top 100 most listened songs per week, between 1990 and 2015 on 4 services, in 10 different countries (France, United States, etc.) | Musical aesthetics | Disparity: Euclidean distances between the acoustic metadata of the tracks of the same top |

| Anderson et al. (2020) | Listener demand, illustrated by the listening history of 100 million different Spotify users during the month of July 2019 | Musical aesthetics | Disparity: Generalist-specialist score (GS score) |

| Bourreau et al. (2011) | Demand from listeners, illustrated by weekly figures for physical sales of recorded music in France, between 2003 and 2008 (GFK database). Supply is approximated by new entries in sales registers on the same sample | Titles, artists, distributors | Variety: Number of occurrences of each category. Balance: Percentage shares of each category, Herfindahl-Hirschman concentration index. Disparity: Rate of renewal in the sample, rate of similarity of the sample, number and concentration of artists and distributors |

| Alexander (1996) | Demand from listeners, approached by the weekly Billboard Top 40 in the United States between 1955 and 1988 | Distributors, musical aesthetics | Balance: Herfindahl-Hirschman index. Disparity: Entropy index of the sample |

| Lopes (1992) | Demand from listeners approached by the annual Billboard Top 100 in the United States between 1969 and 1990 | Titles, albums, artists, distributors | Variety: Number of occurrences of each category. Balance: Percentage share of each category. Disparity: Number and share of new entries in the sample |

| Peterson and Berger (1975) | Demand from listeners, approached by the weekly Top 10 songs in the United States between 1948 and 1973 | Albums, distributors | Variety: Number of occurrences of each category. Balance: Percentage share of each category |

| Audiovisual industry | |||

| Farchy and Ranaivoson (2011) | Offer of programs from six TV channels in 3 countries in November 2009 | Type of programs | Variety: Number of occurrences of each category. Balance: Percentage shares of each category, Shannon’s concentration index, Hill’s variety/balance index. Disparity: Euclidean distances between features. Diversity: Synthetic Stirling index |

| Van der Wurff and Van Cuilenburg (2001) | Offer of programs from the 9 TV channels in the Netherlands between 1988 and 1999. Demand for programs illustrated by the audience figures for these 9 channels over the same period | Genre of programs | Variety: Number of occurrences of each category. Balance: Herfindahl-Hirschman concentration index |

| Napoli (1997) | Offer of programs on three major US TV groups in November and December 1995 | Type of programs | Variety: Number of occurrences of each category. Balance: Herfindahl-Hirschman concentration index |

| Film industry | |||

| Coate et al. (2017) | Offer of films in theatres in Australia in 2013 and 2014. Demand for films is illustrated by the number of screenings over the same period | Nationality of productions | Variety: Number of occurrences of each category. Balance: Herfindahl-Hirschman concentration index |

| Park (2015) | Offer of films in theatres in Australia between 1999 and 2009. Demand for films illustrated by box office receipts over the same period | Nationality of productions | Variety: Number of occurrences of each category. Balance: Percentage share of each category, Simpson’s index. Disparity: Cultural distance between countries |

| Lévy-Hartmann (2011) | Offer of films illustrated by the cinema and videogram releases of 5,650 films between 1998 and 2004. Demand for films is illustrated by the number of copies of videograms and cinema tickets sold over the same period | Structure of production, language of expression, nationality of production | Variety: Number of occurrences of each category. Balance: Percentage shares of each category, Berger-Parker concentration index, Herfindahl-Hirschman concentration index, McIntosh equilibrium index. Disparity: Euclidean distances between features. Diversity: Synthetic Stirling index |

| Moreau and Peltier (2004) | Offer of films in 6 territories between 1990 and 2000. Demand is approximated by the number of admissions per head for each film | Titles, nationality of production | Variety: Number of occurrences of each category. Balance: Herfindahl-Hirschman concentration index |

Literature review.

In the audiovisual sector, works mostly focus on measuring the diversity of the television or cinema supply (Napoli, 1997; Farchy and Ranaivoson, 2011) or on a mix between supply and demand (Van der Wurff and Van Cuilenburg, 2001; Moreau and Peltier, 2004; Lévy-Hartmann, 2011) as in the publishing market (Benhamou and Peltier, 2007). In recorded music, most measures focus on the diversity of demand, approached by the Top charts (weekly, annual, etc.) (Peterson and Berger, 1975; Lopes, 1992; Alexander, 1996; Anderson et al., 2020; Bourreauet al., 2022), and fewer paper tend to focus on the diversity of supply (Bourreau et al., 2011).

Considering the choice of diversity criteria, the genre of the program is favoured in the audiovisual sector (Napoli, 1997; Van der Wurff and Van Cuilenburg, 2001; Farchy and Ranaivoson, 2011) and in cinema, the most chosen criterion corresponds to the nationality of the productions (Moreau and Peltier, 2004; Lévy-Hartmann, 2011). In music, more diverse criteria are utilised (distributors, musical aesthetics, artists, etc.) as in the book sector (authors, publishers, genres, language, etc.).

Most works pay homage to Stirling’s typology in terms of “diversity dimensions” (Stirling, 2007), but do not always explain why they retain this or that dimension. The most recent works choose to explore in particular the dimension of disparity, which is more difficult to grasp than the other (Bideau and Tallec, 2022; Bourreau, Moreau, and Wikström, 2022). The implementation of acoustic metadata attached to songs has made it possible to objectify the difference of “acousticity” separating the songs. Some works use this metadata (see infra) to measure the disparity on the Top 100 most listened tracks out of five music services between 1990 and 2015.

Table 1 shows that at each of the necessary steps, the methodological choices adopted could be more discussed. For example, the choice of sample, never explained under the prism of the availability of relevant data, is sometimes relegated to a simple footnote.

Building diversity measurement indicators: a three-step approach

The study of this previous literature, despite not being explicitly classified into the same methodology, led us to identify a common analysis framework that consists of three key stages to any cultural diversity measurement: the sample selection, the choice of the criterion and the application of the measurement with associated indicators. The following section is therefore dedicated to the presentation of the methodology we propose and the explanation of its importance to perform any cultural diversity measurement, and to provide precise information to the regulator.

Samples selection

First comes the question of the choice of the sample on which a measurement of diversity is carried out. Are we trying to analyse the diversity of the supply, of the demand? In physical places? On online services? In which sector? Considering which companies? The choice depends on the questions to be answered, as well as the data available over a given period. The diversity of supply, for example, to which the attention of the public authorities has focused, may in no way correspond to the diversity of uses, given the concentration of demand on “star” productions (Rosen, 1981). Home access to Portuguese films or Finnish documentaries, which is technically possible, does not prevent the public from focusing on the few blockbusters they have heard of. To promote the diversity of demand, incentive measures can be taken, but no public policy has ever ventured to define obligations in terms of demand. Indeed, the diversity of demand cannot be decreed, but is forged in the long run through an ambitious policy of education, transmission and taming of multiple forms of imagination. This diversity of demand is well documented in the field of cultural sociology, particularly in connection with the notion of “omnivorism” (Peterson and Berger, 1975; Coulangeon, 2003).

Relevant criteria

Once the sample has been chosen, it must be broken down into categories based on the selected criteria. This step, while being central in the diversity analysis, as this choice can lead to several outcomes (sometimes contradictory), remains confusing. Many papers, as shown in the previous section (Measuring cultural diversity: the contribution of academic works section) chose to consider several diversity criteria at once, but this choice may be discussed regarding the policy objective: what are the relevant diversity criteria for evaluating the results of a policy? Should priority be given to the nationality of productions, as required by the European audiovisual regulator, to the diversity of languages as required by the French regulator for radio, to the diversity of budgets, to the diversity of aesthetics, to novelties, to emerging talents, to freelancers, etc.?

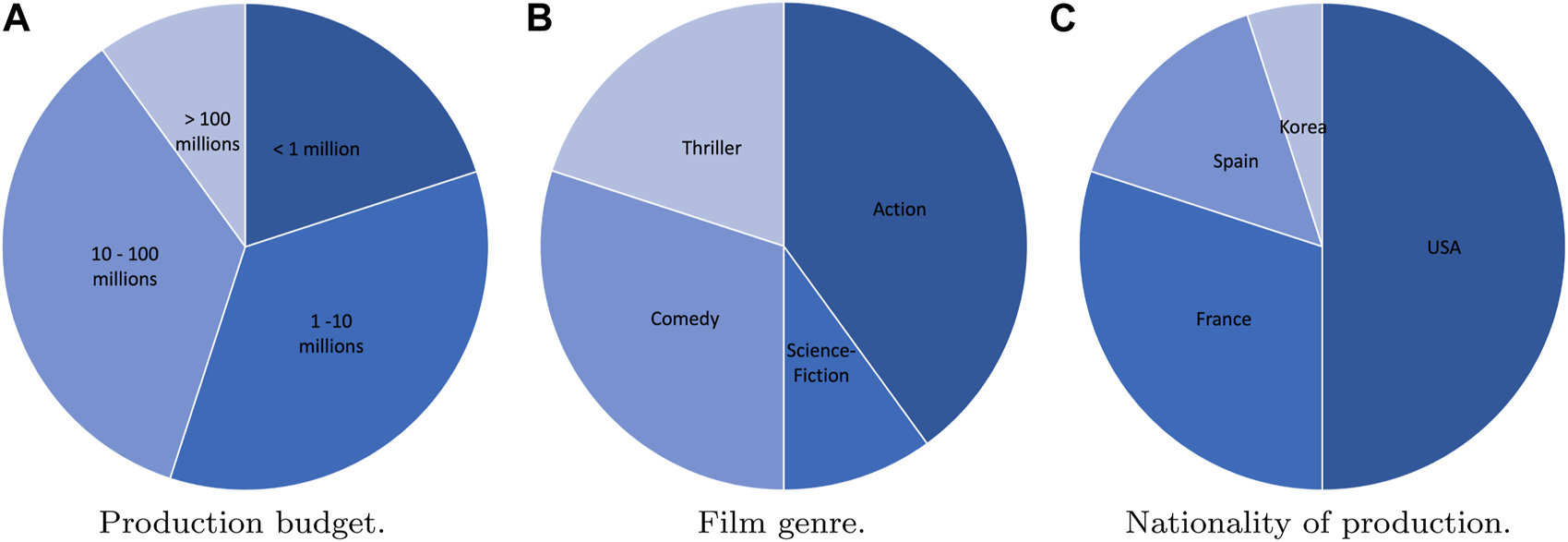

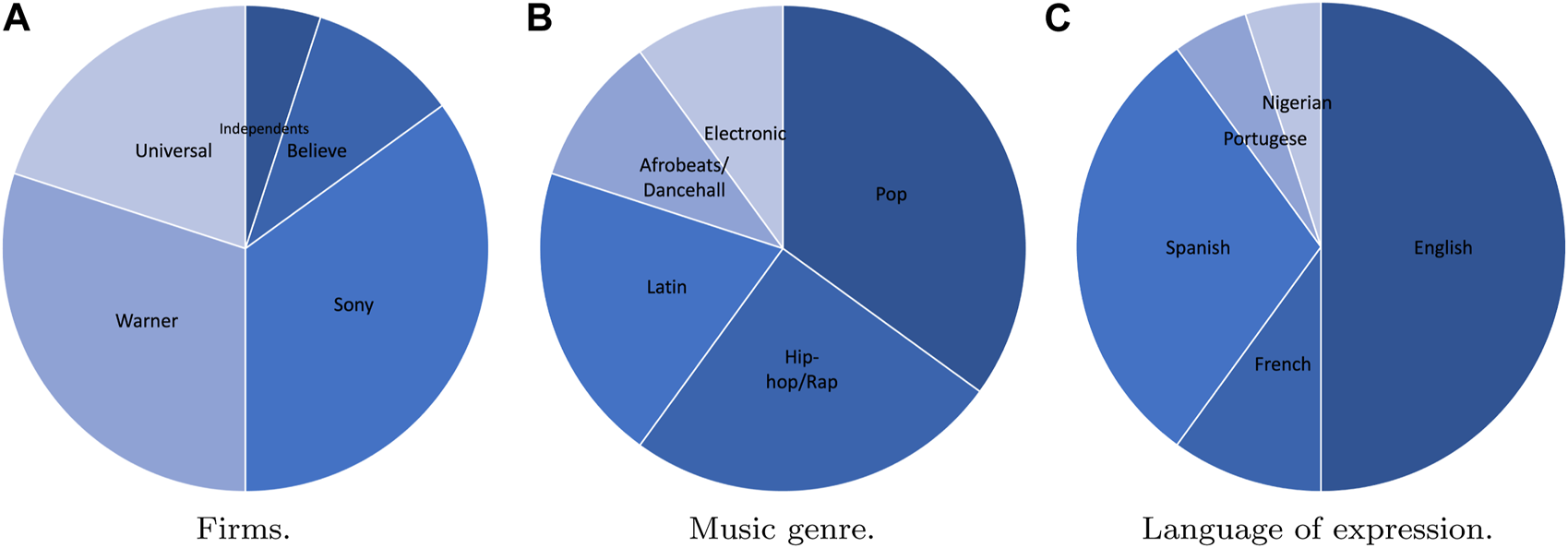

Figures 1, 2 provide, by way of example, criteria that can be applied to various samples in the cinema sector (nationality of production, film genre, budget), and in recorded music sector (music genre, language of expression, diversity of firms). Both the Figures show that many criteria can be applied to the same cultural industry, and their result may be different. For example, Figure 1, in the audiovisual sector, shows us that the criteria used in the audiovisual sector may be: the film genre, the nationality of production or the size of the production (given by its budget). However, while the researcher or the evaluator of the policy may have the choice to consider this or that criterion, the policymaker has already chosen: the AVMS directive is, for example, only centred around the nationality of production across Europe. Hence, to evaluate such a policy, the criterion that must be chosen is the nationality criterion.

FIGURE 1

Examples of diversity criteria in the film industry. (A) Production budget; (B) Film genre; (C) Nationality of production.

FIGURE 2

Examples of diversity criteria in the recorded music industry. (A) Firms; (B) Music genre; (C) Language of expression.

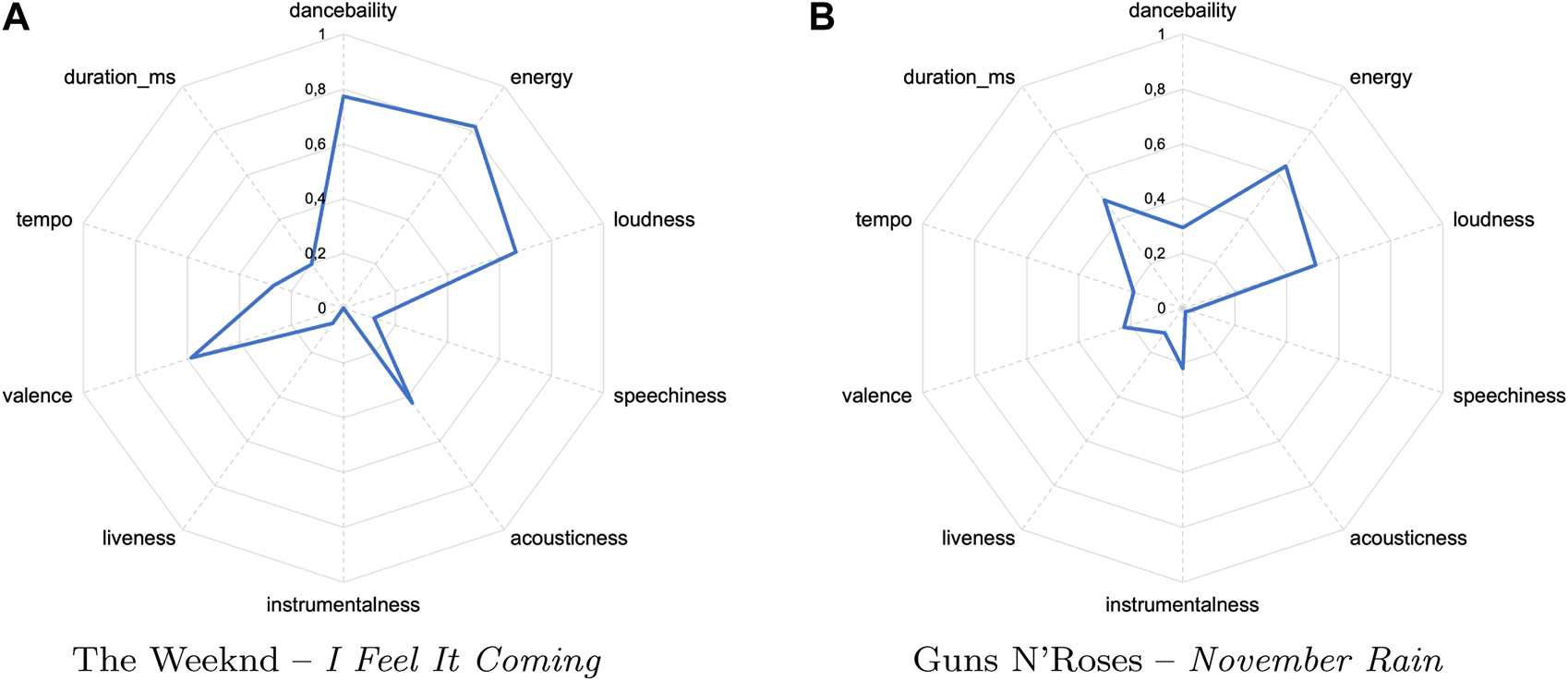

The abundance of available data on online services now makes it possible to measure cultural diversity according to criteria that could previously be considered too subjective, such as the “music genre” of a track. Thus, acoustic metadata is now used by a part of the literature to be able to approach the musical aesthetics of a piece. On Spotify, this metadata is available under the name “Audio features,” and provides a measurement of 13 indicators characterising the sounds of a song in an equivalent manner across the entire service (Figure 3). These metrics provide a good estimate of the perception of music, while being less controversial than the “classic” typologies of musical genres (Rap, Jazz, Rock, etc.) (Askin and Mauskapf, 2017). Some works are therefore now approaching the diversity of musical genres thanks to this type of metadata (Bourreau et al., 2022).

FIGURE 3

Examples of audio features associated with two tracks on Spotify.

The triple dimension of diversity

A final methodological choice relates to the diversity dimensions. Studies in the economics of culture, taking up results from the literature on biodiversity, technological diversity, or the constitution of financial portfolios, and in particular the work of Stirling (1998), Stiriling (2007), have proposed to understand diversity through three dimensions: variety, balance and disparity.

Variety

Variety corresponds to the number of categories within the sample, regarding the criterion selected (for example, the number of languages or the number of distributors present in each sample).

Balance

Balance indicates in what proportion the sample is distributed between the different categories. Steiner (1952) already emphasised the phenomenon of duplication when providers, for example, two radio stations, offer the same type of program. Duplication can be defined by an increase in the choice supplied which concerns an existing category that is already well-represented or even over-represented in the supply. Balance consists in measuring the concentration of each sample: a very concentrated sample is characterised by a small number of actors sharing a large part of the total, conversely, a poorly concentrated sample includes a large number of actors sharing a small share of the total (i.e., a fairer distribution of the sample). Several concentration indicators exist; the Herfindahl-Hirschman index (HHI) is the most widely used in economics; indeed, it represents market shares well, while being less sensitive to the number of categories than other indexes (this last point often resting on the quality of the available data) (Benhamou and Peltier, 2007). A low index (between 0 and 1,000) indicates that the sample is not very concentrated, a medium index (between 1,000 and 2,000) corresponds to an average concentration and a high index (more than 2,000) indicates a high concentration of the sample.

Disparity

Disparity, finally, specifies the extent to which a category is distant from the others. As Jean-Luc Godard noted at the time of the cable TV boom, the forty additional channels in France, did not bring one more Griffith film to the screens; hundreds of television channels, thousands of digital offers, can coexist and still broadcast similar content. This multidimensional approach makes it possible to understand that diversity is not solely a function of variety (i.e., of the number of categories represented). Disparity is the degree of difference between each category within the sample. The disparity dimension is identified by the literature as being the most difficult to grasp. Regarding the language criterion, an exploration of linguistic work on language families could make it possible to estimate the degree of difference between two languages of expression. For the criterion of musical genres (see supra), the advantage of using acoustic metadata is that of an easier measurement of disparity, because each track is directly comparable to another according to the value of each one’s metadata.

The three-step approach is essential to any scientific activity in the measurement of diversity: selection of the sample to be processed, choice of the diversity criterion and the preferred diversity dimensions. These methodological choices must not be made implicitly, but on the contrary made explicit, including when they are simply constrained by the available data. Once the sample has been chosen and the diversity criteria selected, it is possible to distinguish these three dimensions, and to propose measurement indicators for each. Stirling has also proposed a synthetic indicator corresponding to the three dimensions simultaneously (Table 2).

TABLE 2

| Dimensions of diversity | Examples of indicators |

|---|---|

| Variety | Number of occurrences of each category |

| Balance | Share of each category in the sample |

| Herfindahl-Hirschman concentration index | |

| McIntosh concentration index | |

| Shannon concentration index | |

| Disparity | Euclidean distance between categories |

| Proportion of new categories in the sample | |

| GS-Score | |

| Synthesis indicator | Stirling index |

Dimensions of diversity and examples of associated indicators.

Once the methodological choices adopted have been perfectly defined, objective measures of diversity can be available.

The central role of recommendation for cultural diversity

At the turn of the 21st century, cultural globalisation is changing in nature; the rise of online platforms offers a new face to the international circulation of content and to diversity issues in both audiovisual and music sectors. New players, streaming platforms, are now at the centre of the activity of the sector by supporting the marketing of dematerialised on-demand content; streaming via subscription represents 58% of the French recorded music market in the first half of 2022, with a turnover of 211 million euros (out of a total of 364 million euros). At the end of 2022, the European streaming market represented 68% of music listening, with a total of 524 million users.6 The world leader in music streaming, Spotify, globally present in the distribution of musical works also offers non-musical audio content (podcasts, audiobooks, etc.). In audiovisual, 66% of French Internet users are subscribed to a streaming service in2022,7 and VOD streaming represents 30% of audiovisual revenues in Europe in 2021.8

Recommendation and highlighting

One of the consequences of the digital distribution transformation is the proliferation of online content. The abundance of cultural products has in turn spurred new interface design standards. Any on-demand service implies a hierarchy in the presentation of content to users. McKelvey and Hunt (2019) have rightly pointed out that the discovery of content by the user relies heavily on the design and management of choice in platform interfaces. Placement of content does not happen by chance. Among the determinants that explain the place of content on the interface, recommender systems play a major role. Recommendation refers to the set of measures aimed at directing the user towards a particular content or group of contents. Recommendation plays a prescribing role in online services that is much more important than that previously exercised by the usual forms of prescribing that have always existed in the cultural industries (Belleflamme and Peitz, 2018).

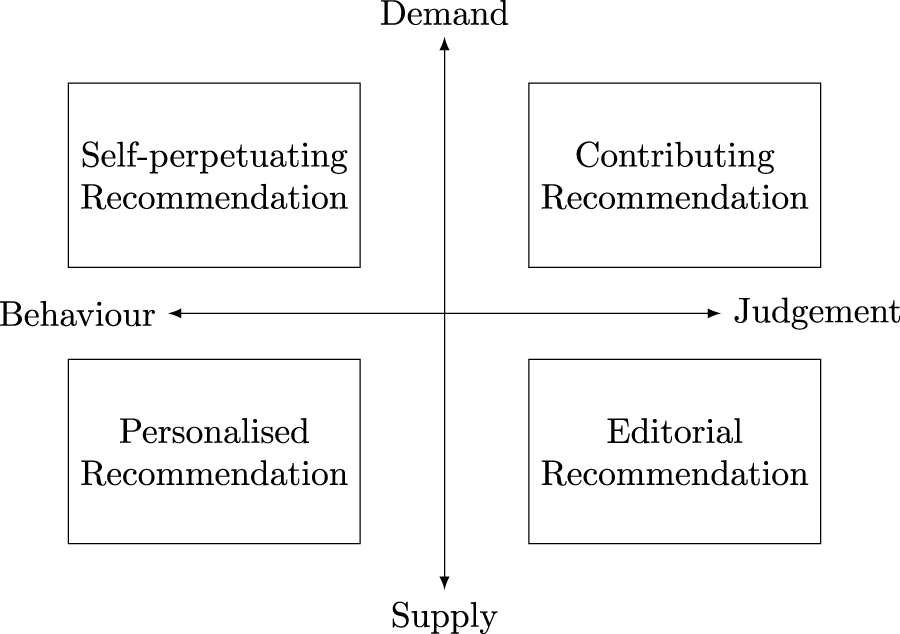

The generic term “recommendation” actually refers to a plurality of systems that raise very different diversity issues. The typology of Farchy et al. (2017), distinguishes four highlighting devices (Figure 4). First, contributory recommendation corresponds to the creation and the sharing of recommendations by users (or third parties). Self-perpetuated recommendation corresponds to the “tops” available on the service. Editorial recommendation refers to content that is highlighted by the platform, for various reasons, for all users, regardless of their individual preferences. Lastly, with the rise of cultural services accessible online, and the volume of content available, the possibility of exploiting a large quantity of usage data on Internet users’ behaviour has led to the emergence of personalised recommendation, associated with the potential of automated algorithmic processing.

FIGURE 4

Recommendation typology.

Most online services like Netflix or Spotify use a mix of these different forms of recommendation (Farchy et al., 2014). The new online music curators thus combine human editorial work and consumer usage data to create a sort of “augmented editorial power” thanks to big data (Bonini and Gandini, 2019). Aguiar and Waldfogel (2021) show that Spotify editorial playlists play an important role in the success of the titles placed there. Mariuzzo and Ormosi (2020) insist on the fact that the music majors, unlike independents, are much more present on the “star” playlists, put forward by Spotify and which accumulate the most audience, which gives the titles of these majors more chances of being visible and listened to.

Recommendation and cultural diversity approaches

By highlighting certain content more than others, recommendation systems influence cultural diversity. But in which direction and how to measure it? Two changes must be considered.

First of all, for services with large catalogues, the mere presence of a title in their catalogue does not necessarily imply that the user can discover it, the relevant sample for measuring cultural diversity is no longer the whole of the supply—the vast catalogues of Netflix or Prime Video each bring together around 5,000 titles in France and that of Spotify more than 100 million tracks worldwide9—but a selection of content that is particularly visible to users, i.e., playlists for music services, or home pages for audiovisual services.

On the other hand, on a service that makes extensive use of personalised recommendation, the analysis of diversity would require two methodological steps; in addition to a classical static analysis of diversity at time t, diversity can be analysed dynamically in order to isolate the effect of personalised recommendation algorithms on diversity, by comparing, using pre-established measurement indicators, the situation before and after the personalisation carried out by the service. The question would not be “How diverse the catalogue is?” but “How diverse are the contents displayed on one specific user’s screen after a recommendation?”. Understanding how recommendation algorithms influence the way in which Internet users are exposed to diversity is indeed a field that could be more explored with all the data available. For scholars, empirical work on case studies would make it possible to measure, without preconceived ideas, the results of recommendation systems on diversity. This analysis makes it possible to specify the existence or non-existence, depending on the services, of “filter bubbles.” The hypothesis of the user being locked into a filter bubble is largely associated with biases linked to the increasingly fine-grained and increasingly in-depth personalisation of the results offered, whether by search engines, social networks, or cultural services. Considering the offer supplied by online cultural services, the thesis of algorithmic biases and confinement in the same category of content, to the detriment of cultural diversity, although recurrent, has never been fully tested in empirical work (Farchy and Tallec, 2023). Establishing appropriate forms of regulation, however, requires detailed, case-by-case analyses in order to confirm or alleviate the fears expressed by the filter bubble hypothesis.

Recommendation and quotas policy in favour of cultural diversity

The recommendation strategies set up by streaming services impact public policies that are in favour of the promotion of diversity. Faced with the major upheavals of the recommendation, public policies nevertheless continue, in order to promote cultural diversity, to mobilise regulatory tools such as quotas, put in place back in the era of an offline world.

Since 1989 in the audiovisual sector, the Council of Europe and the European Commission have attempted to impose broadcasting quotas for European productions. While their initial purpose (as announced in the treaties) was linked to a form of industrial protectionism, quotas have increasingly been claimed as tools for promoting cultural diversity. The criterion of nationality of audiovisual productions (i.e., that of the nationality of production companies) is the only diversity criterion that was retained to establish these quotas. However, “European” content is neither a cultural category nor an economic category but only a “political” category.

Unlike the audiovisual sector, the question of quotas in the music industry is not subject to Community regulations. The French national choice is an exception within the European Union. The criteria used by the French public authorities in the music industry are those of the language of expression and the release date of the titles. France chose to impose quotas for French-language works on private radio stations as early as 1986: the law of 30 September (modified on 1 August 2000) provides that “the substantial proportion of musical works of French expression or interpreted in a regional language in use in France must reach a minimum of 40% of songs of French expression, of which at least half come from new talents or new productions.”

With the rise of online services, in the audiovisual field, the political ambition to modify the rules of the market by directing users towards certain types of content -European ones—through “highlighting” processes, has materialised in the AVMS Directive in 2018: it now requires that nearly one-third of their catalogues contain European works. Nothing like that is contemplated at this point in the music industry but some professionals are already calling for a similar type of regulation by setting up quotas.

Yet, promotion quotas are relics of a bygone, broadcast television or radio-dominated era, and are thus unsuited to on-demand services. In a non-linear situation where users have the ability to decide the time at which they view or listen to content, it seems irrelevant to impose the players to ensure a presence rate of European content in their catalogues if this content is not highlighted by recommendation. The role played by recommendation systems leads to question the relevance of old means of regulation, that of quotas, in a radically different ecosystem.

Mobilising available indicators to serve a new regulation of cultural diversity

Beyond the incantatory discourse on the supposed benefits of cultural diversity, public authorities, when they do not rely on any statistical indicator, tend to display vague objectives.

The ambiguous objectives of policies in favour of cultural diversity

Historically, in international negotiations, this question of diversity is at the heart of the recurring debate between liberalism and protectionism. Faced with the imbalance of international trade, protectionist temptations rose up, from the 1930s, to an essentially European/American confrontation in the film industry, before expanding to the entire audiovisual sector. The agreement signed in 1994 by the member countries of the GATT—now the World Trade Organisation (WTO) –, the famous “cultural exception”, leads to a complex situation in which Europeans have made no commitment to liberalise the audiovisual sector, and obtained provisionally to preserve the existence of their public support mechanisms. The policy of cultural exception has become the symbol of the resistance of all cultural activities to the laws of the market, although the culture in question, as it is envisaged in the WTO negotiations, remains almost exclusively centred on cinema and audiovisual. It means that culture is different from other goods, because of its symbolic dimension and the values it conveys, and therefore must constitute an exception to the rules of free trade.

While the notion of exception was clearly associated with a protectionist ambition in the context of trade negotiations, the vaguer notion of cultural diversity has gradually imposed itself in national and international debates, a somewhat “soft” political objective. The display of an ambitious policy in defence of cultural diversity is sometimes only the screen of a classic policy of protectionism in favour of national industries (Farchy et al., 2022). The idea that national public authorities must protect diversity, faced with the presumed cultural homogenisation to which free trade would lead, occupies a central place in Europe. Behind the common banner of promoting cultural diversity, however, strong political opposition remains between the countries, and unlike the audiovisual industry, the music industry has received little attention regarding the issue of diversity.

The existence of content produced by National or European companies in each country is far from being a guarantee of cultural diversity. The objective of cultural diversity therefore contains a great ambiguity: is it a question of allowing companies whose capital is French, Spanish or Swedish to manufacture images and sounds? Only classic benefits to local industries would then be expected. Or is it to encourage the production of works different from those offered by the United States, India, Brazil or Korea and to disseminate European culture more widely on international services? Similarly, aiming to maintain a variety of small and medium producers and distributors will not necessarily lead to a great disparity of musical genres if everyone seeks to duplicate the genres that perform best.

At the end of semantic shifts, protectionism for the benefit of European economic sectors has therefore, falsely, become synonymous with the diversity of cultural identities conveyed by the contents. Beyond this historical ambiguity, choosing suitable measurement indicators could be an opportunity to clarify, in a pragmatic manner, the objectives pursued.

Choosing indicators adapted to the objectives pursued

The Table below (Table 3) provides an overview, in the case of online music streamed on Spotify, of possible approaches to measuring diversity. Monitoring associated indicators correspond to different objectives. As we have noted, measuring diversity presupposes, methodological choices: the identification of the relevant samples, the choice of the appropriate diversity criteria and finally that of the dimensions of the diversity to be measured (and the associated indicators). Public decision-makers must therefore carry out arbitration (bearing in mind that depending on the criteria selected, the effects may prove to be contradictory), and regularly evaluate, thanks to appropriate measurement tools, the results of the means implemented.

TABLE 3

| (a) Criterion—Languages |

| Sample—Top 100 most listened tracks |

| Dimensions |

| Variety: number of different languages available in the Top |

| Balance: share of French or English within the sample |

| (b) Criterion—Publishing firms |

| Sample—Most followed editorial playlists |

| Dimensions |

| Variety: number of firms inside the sample |

| Balance: shares of majors/independent publishers within those playlists |

| (c) Criterion—Music genre of the tracks |

| Sample—Top 1,000 |

| Dimensions |

| Variety: number of music genres |

| Balance: shares of these genres |

| Disparity: proximity metrics between multiple music genres (with the use of acoustic metadata, for example) |

| (d) Criterion—Emerging of new artists |

| Sample—Whole of editorial playlists |

| Dimensions |

| Variety: number of new artists highlighted by editorial recommendation |

| Balance: relative share of new artists within the entire artists set within editorial recommendation |

Multiple approaches of cultural diversity measurement.

We have selected four diversity criteria (the musical genre, the distribution company, the language of the titles and the novelty of the artists) which can be associated with one or other of the dimensions of diversity. Depending on the preferred angle, the diversity indicator will not be calculated in the same way and the result obtained will have to be interpreted differently.

The choice of the sample (the Tops, the editorialised playlists, etc.) corresponds to different questions. The diversity resulting from the content highlighted by the self-sustaining recommendation (the Tops) sheds light on the observed diversity of demand. The analysis of samples of editorialised playlists allows, from a different angle, to calculate the diversity of content highlighted according to the strategy driven by the platform.

Likewise, the choice of diversity criteria does not follow the same expectations. If the objective is to maintain a fringe of independent distributors in relation to the oligopoly (Sony, Warner, Universal, Believe) the relevant criterion will be that of the firms. If it is a topic of questioning the predominance of urban music, the criterion to remember will be that of musical genres. The diversity of genres can be understood by defining predetermined genres ex-ante or, on the contrary, on the basis of acoustic metadata (see above), determining the greater or lesser acoustic diversity of the titles. The number of different artists in playlists and the identification of “new entrants” (who offer their first tracks) gives an additional indication of the sector’s capacity to renew itself. Finally, if the objective is the defence of the “Francophonie,” monitoring a linguistic diversity indicator will prove useful. Depending on the diversity criterion chosen, contradictory results may appear. Thus, the linguistic protectionism of French (see infra) can lead to paradoxes, by setting aside certain non-sung or non-spoken musical genres (such as music called “classical” or certain forms of electronic music) and excluding French (or French-speaking) artists, choosing to express themselves in another language (Daft Punk, Rilès, etc.).

Conclusion

Diversity indicators, while they do not replace a policy, nonetheless remain compasses, valuable decision-making tools in a rapidly changing cultural universe increasingly impacted by technological changes. Rather than setting up quotas, which are largely unsuitable for de-linearized services, a policy in favour of cultural diversity could be based, beforehand, on the choice and monitoring of a certain number of diversity indicators corresponding to the preferred objectives. This article offers a methodological reference framework for empirically developing new indicators on which regulators and companies could rely.

Once implemented, indicators of cultural diversity should be regularly published. Monitoring could be carried out either directly by a dedicated Observatory of cultural diversity, or be subject to a requirement for transparency on the part of online services which would publish at regular intervals the requested indicators concerning them. Bulk data and diversity indicators could be available. Failing to address this, public authorities will condemn policies in favour of cultural diversity as being nothing more than wishful thinking, without substance.

Statements

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

JF and JM’B wrote the manuscript and have been involved in all the process of this article’s redaction. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Footnotes

1.^European Parliament, Directive 2007/65/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council, 2007. Available at: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/dir/2007/65/oj.

2.^European Commission, Communication from the Commission to the Council, the European Parliament, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions - The Future of European Regulatory Audiovisual Policy, 2003. Available at: https://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/42254032-40a3-41d7-b7b8-79f4834d60b3/language-en.

3.^European Parliament, Directive (EU) 2018/1808 of the European Parliament and of the Council, 2018. Available at: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/dir/2018/1808/oj.

4.^This article does not address the question of the diversity of people and the representation of women and visible minorities in cultural sectors, but only the question of the diversity of supply and demand for cultural content.

5.^French Ministry of Economy and Finances, expenditure performance, Culture mission. Available at: https://www.budget.gouv.fr/performance-depense?annee=118&type_budget=all&mission=33409.

6.^GESAC—European Grouping of Societies of Authors and Composer, Study on the place and role of authors and composers in the European music streaming market, 2022. Available at: https://authorsocieties.eu/content/uploads/2022/09/music-streaming-study-28-9-2022.pdf.

7.^ ARCOM, 2022 Barometer of the consumption of digital cultural goods, 2022. Available at: https://www.arcom.fr/nos-ressources/etudes-et-donnees/mediatheque/barometre-2022-de-la-consommation-des-biens-culturels-dematerialises.

8.^European Audiovisual Observatory, Top players in the European AV industry, 2023. Available at: https://rm.coe.int/top-players-in-the-european-av-industry-2022-edition-l-ene/1680a9cb32.

9.^Spotify, About Spotify. Available at: https://investors.spotify.com/about/.

References

1

Aguiar L. Waldfogel J. (2021). Platforms, power, and promotion: evidence from Spotify playlists. J. Industrial Econ.69 (3), 653–691. 10.1111/joie.12263

2

Alexander P. J. (1996). Entropy and popular culture: product diversity in the popular music recording industry. Am. Sociol. Rev.61 (1), 171–174. 10.2307/2096412

3

Anderson A. Maystre L. Anderson I. Mehrotra R. Lalmas M. (2020). Algorithmic effects on the diversity of consumption on spotify. Proc. Web Conf.2020, 2155–2165. 10.1145/3366423.3380281

4

ARCOM (2022). Ecoute de la musique en streaming audio - analyse et comparaison avec la radio (tech report).

5

Askin N. Mauskapf M. (2017). What makes popular culture popular? Product features and optimal differentiation in music. Am. Sociol. Rev.82 (5), 910–944. 10.1177/0003122417728662

6

Belleflamme P. Martin P. (2018). Inside the engine room of digital platforms: reviews, ratings, and recommendations. Germany: University of Mannheim.

7

Benhamou F. Peltier S. (2007). How should cultural diversity be measured? An application using the French publishing industry. J. Cult. Econ.31, 85–107. 10.1007/s10824-007-9037-8

8

Bideau G. Tallec S. (2022). Les fans aiment aussi sur Spotify. Chaire PcEn. Available at: https://pcen.fr/activites/les-fans-aiment-aussi-sur-spotify.

9

Bonini T. Gandini A. (2019). “First week is editorial, second week is algorithmic”: platform gatekeepers and the platformization of music curation. Soc. Media+ Soc.5 (4), 205630511988000. 10.1177/2056305119880006

10

Bourreau M. Moreau F. Senellart P. (2011). La diversité culturelle dans l'industrie de la musique enregistrée en France (2003-2008). Cult. étudesn°5 (5), 1–16. 10.3917/cule.115.0001

11

Bourreau M. Moreau F. Wikström P. (2022). Does digitization lead to the homogenization of cultural content?Econ. Inq.60 (1), 427–453. 10.1111/ecin.13015

12

Coate B. Deb V. Arrowsmith C. Zemaityte V. (2017). “Feature film diversity on Australian cinema screens: implications for cultural diversity studies using big data,” in Australian screen in the 2000s (Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer), 341.

13

Coulangeon P. (2003). La stratification sociale des goûts musicaux: le modèle de la légitimité culturelle en question. Rev. française Sociol.44 (1), 3–33. 10.2307/3323104

14

Donnat O. (2018). Évolution de la diversité consommée sur le marché du livre, 2007-2016. Cult. études3 (3), 1–28. 10.3917/cule.183.0001

15

Farchy J. Benabou V.-L. Méadel C. (2014). “Le référencement des oeuvres sur internet. Technical Report,” in Conseil supérieur de la propriété littéraire et artistique.

16

Farchy J. Bideau G. Tallec S. (2022). Content quotas and prominence on VOD services: new challenges for European audiovisual regulators. Int. J. Cult. Policy28 (4), 419–430. 10.1080/10286632.2021.1967944

17

Farchy J. Méadel C. Anciaux A. (2017). Une question de comportement. Recommandation des contenus audiovisuels et transformations numériques. tic&société10 (2-3), 168–198. 10.4000/ticetsociete.2136

18

Farchy J. Ranaivoson H. R. (2011). “An international comparison of the ability of television channels to provide diverse programme: testing the Stirling model in France, Turkey and the United Kingdom,” in Measuring the diversity of cultural expressions: applying the stirling model of diversity in culture (Paris, France: UNESCO), 77.

19

Farchy J. Tallec S. (2023). De l’information aux industries culturelles, l’hypothèse chahutée de la bulle de filtre. Quest. Commun.43, 241–268. 10.4000/questionsdecommunication.31474

20

Lévy-Hartmann F. (2011). Une mesure de la diversité des marchés du film en salles et en vidéogrammes en France et en Europe. Cult. méthodesn°1 (1), 1–16. 10.3917/culm.111.0001

21

Lopes P. D. (1992). Innovation and diversity in the popular music industry, 1969 to 1990. Am. Sociol. Rev.57, 56–71. 10.2307/2096144

22

Mariuzzo F. Ormosi P. L. (2020). Independent v major record labels: do they have the same streaming power (law)?Available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3729966.

23

McKelvey F. Hunt R. (2019). Discoverability: toward a definition of content discovery through platforms. Soc. Media+ Soc.5 (1), 205630511881918. 10.1177/2056305118819188

24

Moreau F. Peltier S. (2004). Cultural diversity in the movie industry: a cross-national study. J. Media Econ.17 (2), 123–143. 10.1207/s15327736me1702_4

25

Napoli P. M. (1997). Rethinking program diversity assessment: an audience-centered approach. J. media Econ.10 (4), 59–74. 10.1207/s15327736me1004_4

26

Nicolas Y. Gergaud O. (2016). Évaluer les politiques publiques de la culture. Ministère de la Culture - DEPS. 10.3917/deps.nicol.2016.01

27

Park S. (2015). Changing patterns of foreign movie imports, tastes, and consumption in Australia. J. Cult. Econ.39, 85–98. 10.1007/s10824-014-9216-3

28

Peterson R. A. Berger D. G. (1975). Cycles in symbol production: the case of popular music. Am. Sociol. Rev.40, 158–173. 10.2307/2094343

29

Pietrzyk N. (2017). Evolution de la structure de marché de l’exploitation des grandes salles de spectacle et de la diversité des acteurs économiques et des spectacles entre 2010 et 2016 (Tech. Rep.). Ministère de la Culture.

30

Poirrier P. (2016). Les politiques de la culture en France, Paris, La Documentation française, coll. Doc en poche, 888. ISBN: 9782110102492.

31

Rosen S. (1981). The economics of superstars. Am. Econ. Rev.71 (5), 845–858.

32

Steiner P. O. (1952). Program patterns and preferences, and the workability of competition in radio broadcasting. Q. J. Econ.66 (2), 194–223. 10.2307/1882942

33

Stirling A. (1998). “On the economics and analysis of diversity,” in Science policy research unit (SPRU), electronic working papers series. Paper 28: 1–156.

34

Stirling A. (2007). A general framework for analysing diversity in science, technology and society. J. R. Soc. interface4 (15), 707–719. 10.1098/rsif.2007.0213

35

Van der Wurff R. Van Cuilenburg J. (2001). Impact of moderate and ruinous competition on diversity: the Dutch television market. J. Media Econ.14 (4), 213–229. 10.1207/s15327736me1404_2

Summary

Keywords

cultural policy, diversity, music industry, audiovisual industry, streaming services

Citation

Farchy J and M’Barki J (2024) Measuring cultural diversity: policy and methodological issues. Eur. J. Cult. Manag. Polic. 13:12400. doi: 10.3389/ejcmp.2023.12400

Received

10 November 2023

Accepted

19 December 2023

Published

08 January 2024

Volume

13 - 2023

Updates

Copyright

© 2024 Farchy and M’Barki.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Julien M’Barki, julien.m-barki@univ-paris1.fr

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.