Abstract

Based on evidence from two exploratory case studies, the article examines how intangible cultural heritage can promote sustainable rural development by creating value for rural communities. The studied communities in Bavaria, Germany, and Le Marche, Italy, are closely tied to traditional agricultural practices and their historical legacies. In the German case study, alpine pasture farming has sustained its cultural landscape and tourism for generations, while in the Italian case, the rural sharecropping legacy evolved into a culinary heritage project. Bad Hindelang (Germany) stands out as a mature destination with a long history of sustainable tourism, achieved through collaboration between farmers, conservationists, and the local community. The region balances tourism, conservation, and ecological farming through community participation and collective action. In contrast, Le Marche region (Italy) has only recently experienced increasing numbers of international tourists, but seems well-situated to exploit opportunities for cultural and culinary tourism development. The Marche Food and Wine Memories project has preserved the oral memories and the culinary heritage of former sharecroppers, yet economic value for the region has so far been limited. Post-COVID-19, the region may benefit from increased demand for tourism in culturally appealing, authentic and less crowded destinations. The article emphasises that intangible cultural heritage can enrich the quality of life of local residents and enhance visitors’ experiential value. Innovative approaches like storytelling and participatory engagement make these cultural expressions accessible to wider audiences, including tourists, thus benefiting heritage communities in various ways. Both cases highlight the role of innovation, with Bad Hindelang’s eco-model promoting ecological farming and Le Marche’s project preserving sharecroppers’ heritage through corporate heritage marketing. Collaboration among various stakeholders has been a key to success in both cases. The article also illustrates the range of functions fulfilled by intangible cultural heritage, from restoring social dignity to maintaining landscape aesthetics and ecological integrity.

Introduction

As highlighted by the Council of Europe’s Frame Convention on the Value of Cultural Heritage for Society (“Faro Convention”) cultural diversity and intangible cultural heritage are crucial for social cohesion, sustainable development and people’s quality of life (Council of Europe, 2005). The convention presents a paradigmatic shift away from a static, public-sector driven concept of cultural heritage as “exceptional” towards non-static “commonplace heritage” with bottom-up management and a focus on heritage communities (Council of Europe, 2005; Cerquetti and Romagnoli, 2022). As part of a strategic foresight exercise, the International Centre for the Study of the Preservation and restoration of Cultural Property (ICCROM) stresses the future importance of cultural heritage, which “in all its diverse forms and interpretations, should serve to enhance the wellbeing of people and the sustainability of our planet” (Heritage et al., 2023, p. viii). Implicit in the above-mentioned conceptualisations is the notion of “use value,” which has been criticised for the risk of commercialisation and commodification of culture. On the one hand, cultural values can be compromised and corrupted, e.g., due to overtourism and the “touristification” of sites (Vecco and Caust, 2019). On the other hand, use value may contribute to safeguarding and enhancing cultural heritage by attracting resources and increasing community awareness (Cerquetti and Romagnoli, 2022). Recent contributions have thus stressed the importance of valorisation and impact assessments to determine the economic and social value of culture (ESPON, 2020; Ioannou, 2021; SoPHIA, 2021).

However, there is a need to examine in more detail whether and how innovative approaches to cultural heritage management promote sustainable development and enhance the quality of life of heritage communities. Income streams and jobs linked to tangible cultural heritage in the form of “exceptional” heritage sites such as those listed in the UNESCO World Heritage List are relatively straightforward to assess (ESPON, 2020). In contrast, it appears more difficult to determine the cultural, social and economic value of “commonplace,” especially intangible cultural assets that are, nonetheless, very important for a shared cultural identity at the local level. Likewise, the contribution of culture and creative industries to urban renewal and rebranding cities is fairly well-understood (cf. Heritage and Copithorne, 2018; Borin and Juno-Delgado, 2018 for overviews). Less is known, however, about the current and potential role of intangible cultural heritage in promoting value for rural regions. Against this backdrop, this contribution aims to investigate the impact of intangible cultural heritage on sustainable development and quality of life through the creation of value from tourism and other economic activities in rural communities. Based on case study evidence from two rural areas in Italy and Germany the article explores whether intangible cultural heritage linked to traditional agricultural practices creates benefits for rural communities and, hence, contributes to sustainable local development.

In the sections that follow, the conceptual framework and methodology are explained, followed by the presentation of the two case studies. We analyse and compare the two cases, looking at their contributions to safeguarding the concerned regions’ intangible cultural heritage, economic and social impacts on rural communities and potentials for sustainable tourism and (agriculture-based) business development. The article concludes with a summary and discussion of the main findings, as well as some perspectives for other destinations in Europe and elsewhere.

Conceptual framework

Cultural heritage is an object of study within an increasingly transdisciplinary literature, involving scholars from diverse fields such as anthropology, history, geography, management science, sociology, tourism, and conservation. The existence of a common cultural heritage, collectively held by a group of people in a particular spatial context, was first acknowledged by the Venice Charter for the Conservation and Restoration of Monuments and Sites in 1964 (Vecco, 2010). A few years later, in 1972, the UNESCO Convention on the Protection of World Cultural and Natural Heritage stressed the universal importance of cultural heritage, which has to be responsibly managed and safeguarded for the sake of future generations. Natural and cultural heritage are clearly distinguished in this convention, while both are given equal importance. According to the UNESCO convention, cultural heritage refers to monuments, groups of buildings and sites, which are of “outstanding universal value” from the point of view of history, art, science, ethnology, or anthropology, or for their aesthetic properties (UNESCO (United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation), 1972). The Convention’s isolated focus on tangible cultural heritage, however, was soon criticised as too narrow and restrictive, as it excluded the multitude of non-material expressions of culture, which in many cultures and regions, especially outside of Europe, are often relatively more important than the material culture (Vecco, 2010). Consequently, another UNESCO convention was devoted to intangible cultural heritage in 2003 (UNESCO (United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation), 2022). In Article 2 of the 2003 convention, intangible cultural heritage is defined as:

“the practices, representations, expressions, knowledge, skills—as well as the instruments, objects, artefacts and cultural spaces associated therewith—that communities, groups and, in some cases, individuals recognize as part of their cultural heritage. This intangible cultural heritage, transmitted from generation to generation, is constantly recreated by communities and groups in response to their environment, their interaction with nature and their history, and provides them with a sense of identity and continuity, thus promoting respect for cultural diversity and human creativity” (UNESCO (United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation), 2022, p. 5).

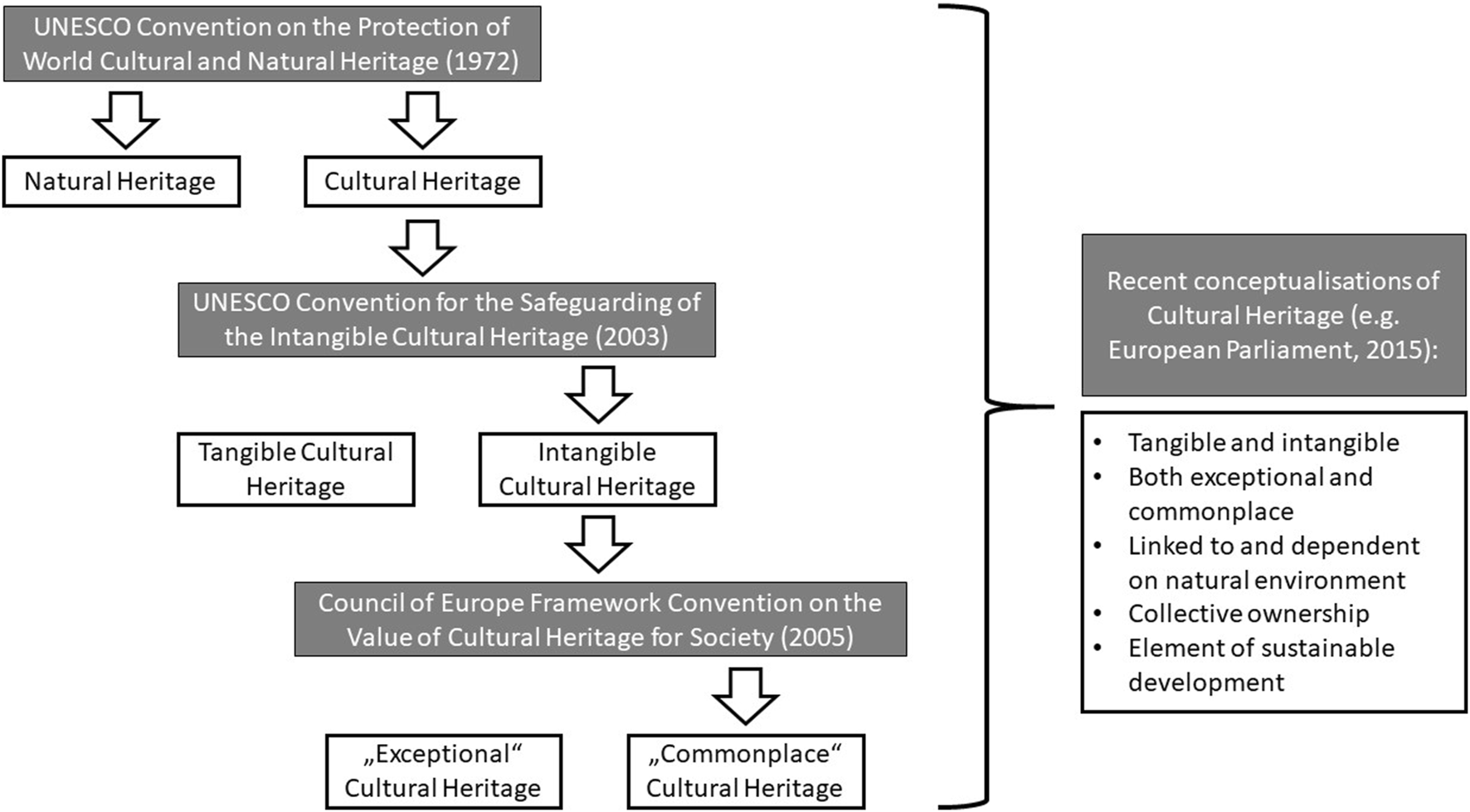

This definition indicates a close link between people’s intangible cultural heritage and their natural environment, promoting a sense of belonging and identity that is tied to a particular territory and natural landscape. It also builds a conceptual bridge to sustainable development and the Agenda 2030 of the United Nations (UN), even if the 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) do not directly refer to cultural heritage as a central pillar of sustainable development (Demartini et al., 2021). This link is explicitly made in the Faro Convention, which highlights the value and potential of cultural heritage as a resource for sustainable development and quality of life (Council of Europe, 2005; Cerquetti and Romagnoli, 2022). In the same vein, the European Parliament (2015) acknowledges that “culture and cultural heritage are shared resources and are common goods and values that cannot be subject to an exclusive use, and their full potential for sustainable human, social and economic development has yet to be fully recognised and properly exploited, both at the level of EU strategies and the UN post-2015 development goals.” The evolution of contemporary notions of cultural heritage is graphically summarised in Figure 1. The contributions in Cameron (2023), however, highlight some of the difficulties in developing and managing cultural heritage resources, including insufficient stakeholder participation, the traditional but artificial separation between culture and nature in heritage conservation and the distinction between tangible and intangible cultural heritage.

FIGURE 1

Evolution of the concept of Cultural Heritage (own compilation).

Conceptually linked to intangible cultural heritage is the notion of heritage community (Cerquetti and Romagnoli, 2022). According to the Faro Convention (Council of Europe, 2005, p. 6), a heritage community has “a variable geometry without reference to ethnicity or other rigid communities. Such a community may have a geographical foundation linked to a language or religion, or indeed shared humanist values or past historical links.” Consequently, heritage communities can be defined at various spatial scales, for instance at the level of a village or town, an administrative district, a region or a nation. In Art. 2 of the Faro Convention, a heritage community is defined as consisting “of people who value specific aspects of cultural heritage which they wish, within the framework of public action, to sustain and transmit to future generations.” Citizens are thus regarded as protagonists and co-designers of cultural interventions rather than mere recipients of public interventions. This notion of heritage communities potentially contributes to sustainable innovation in tourism, as citizens’ willingness to preserve and transmit their culture could promote more authentic encounters and experiences, enhancing tourists’ awareness of and respect for the cultural heritage and the landscape in which it is embedded (Cerquetti and Romagnoli, 2022, p. 45).

As stated above, cultural heritage is expected to create value for heritage communities. It may, for instance, create jobs and contribute to skills development and economic growth through the promotion of tourism (European Parliament, 2015). The concept of value, however, deserves further clarification and must not be confused with the pluralised term values. According to the Cambridge Dictionary, values refer to “the principles that help you to decide what is right and wrong, and how to act in various situations.” As suggested by Borin and Juno-Delgado (2018), values can be regarded as important elements of “cultural ecosystems.” Such ecosystems are united by a regional identity and common cultural values that are shared by different stakeholders in a particular territory. In contrast, the notion of value implies something of worth, important or useful. In this study, value refers to all kinds of benefits that can be linked to the intangible cultural heritage of a defined territory. Apart from economic benefits, such as jobs and income, local stakeholders may also assign value to perceived social and cultural benefits (Borin and Juno-Delgado, 2018). For instance, social and cultural value can be assigned to networks and membership in associations, interpersonal trust, quality of life, cultural or creative enterprises, commonly-shared traditions and collective memories of the past. In line with the concept of sustainable development, it appears adequate to add ecological and environmental benefits as another important value dimension. Use value in this study may thus refer to the economic, social, cultural or environmental benefits to heritage communities that are derived from intangible cultural resources. In addition, experiential value may be created for visitors or customers who “consume” products or services linked to cultural heritage.

Methodology

Exploratory evidence from two case studies is presented to assess the contribution of intangible cultural heritage to sustainable development and quality of life of rural communities, as conceptualised in the framework explained above as economic, social, cultural, environmental and experiential value. Case studies as a method of empirical enquiry are well-suited to investigate abstract concepts and contemporary phenomena in a real world context (Yin, 2003). Due to the inherent connection between intangible cultural heritage, heritage communities and their territory, case studies are particularly valuable to produce concrete, reliable and valid knowledge (Flyvbjerg, 2006). It should be stressed that case studies are neither a particular research method, nor are they an exclusive domain of qualitative research (Ragin, 1987). Hence, both objective, quantitative data (such as available statistics), as well as subjective, qualitative insights (e.g., from the researchers’ personal observations in the field, on-site discussions and online interviews with local stakeholders and experts) have been analysed in order to present the case study findings. Single-case studies are the most common form of case study inquiry. Nonetheless, dual or multiple-case studies are generally preferred over single-case designs (Yin, 2003; Stake, 2006). A two-case study design was chosen not just for comparative reasons, but more importantly to generate insights from diverse settings, looking at one example (Bad Hindelang, Germany) with a history of over 35 years and another more recent example which has evolved from an oral history project (Le Marche, Italy). The cases are located in rural regions of Italy and Germany and were selected due to their commonalities with regard to innovative forms of stakeholder engagement and development of culture-based products. They also serve to illustrate the varied ways how intangible cultural heritage can enhance the experiential value of visitors and customers in rural destinations.

As regards material cultural heritage, both Italy and Germany have a high density of monuments relative to other European nations (ESPON, 2020). Among the state parties that ratified the 1972 UNESCO World Heritage Convention, Italy currently has the largest (58 sites) and Germany the third largest (51 sites) number of inscriptions on the list of cultural and natural heritage sites. Together, the two countries represent almost a third of the EU’s population and roughly 16% of its surface area. In terms of per-capita GDP, Germany is above (117%) and Italy slightly below (96%) the EU average (EUROSTAT, 2023). Despite their absolute and relative wealth, both countries possess a considerable area of “inner peripheries,” i.e., territories with poor economic or demographic potential and/or poor access to services. To overcome regional disparities in such peripheries, the development of infrastructure and connectivity, social innovations, networks, exogenous linkages and territorial capital have been proposed (ESPON, 2017). Intangible cultural heritage appears as one possible type of “territorial capital” that could contribute to regional development in such peripheries. To scrutinise this proposition, the case studies investigate the role of intangible cultural heritage in two particular geographic settings, describing the heritage communities and assessing the various types of value that can be linked to such assets.

Several years after Italy (2007), Germany ratified the UNESCO convention on intangible cultural heritage in 2013. In response to Article 16 of the convention, UNESCO maintains a Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity to “help demonstrate the diversity of this heritage and raise awareness about its importance.” The Register of Good Safeguarding Practices contains programmes, projects and activities that “best reflect the principles and the objectives of the Convention” (UNESCO (United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation), 2023). Including the latest (2022) additions, UNESCO lists 567 elements on the Representative List and 33 Good Safeguarding Practices. Among these are 17 elements related to Italy and seven to Germany. Another 76 elements are listed as requiring “urgent measures to keep them alive” (UNESCO (United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation), 2023). Apart from the global inventory, member states of the convention keep nationwide lists of intangible cultural heritage. Germany’s Nationwide Inventory of Intangible Cultural Heritage currently lists 144 elements: 128 cultural practices and expressions, and 16 examples of good safeguarding practices.

The first case examines the “High Alpine Agriculture in Bad Hindelang,” which is inscribed in Germany’s national register of intangible cultural heritage as an example of “good safeguarding practices” (German Commission for UNESCO, 2023). Mobile livestock management on pastures at varying altitudes is a sustainable form of land use typical for and widespread throughout the Alps (Bätzing, 2015; Bätzing, 2021). In Bad Hindelang, the cultural practices related to traditional land management have been well-preserved and are closely linked to tourism development in the region. The Italy case study explores the use value of the “Marche Food and Wine Memories” project. The project is a private-sector initiative, driven by a winery in connection with a start-up company in Offida, a village in Le Marche region. The project is based on the oral memories of the region’s last sharecropping farmers. Sharecropping is a system of land tenancy in which landowners allow landless farmers, the sharecroppers, to till the land in return for a share (usually 50%) of the crop produced on the land. While this practice had disappeared in most parts of Italy, it was still common in the Marche region until the second half of the 20th century (Cerquetti et al., 2022).

As typical for case studies, this article draws on a range of published and unpublished sources, data and materials, including project reports, scientific articles, monographs, websites, field visit notes and protocols, photo and video documentations, observations, and formal and informal qualitative interviews and group discussions with local residents, experts and other stakeholders. More specifically, research for the Bad Hindelang case study included on-site and online interviews with tourism stakeholders, experts and members of the local farmers’ association to gain insights into the evolution of the “eco-model” of sustainable farming and to assess its achievements to date. The Italian case study is based on narrative interviews conducted with 100 former sharecroppers in 17 villages of Le Marche region. This interview technique was not intended to gather exact data or statistics but rather to encourage the interviewees, many of whom were illiterate, to communicate personal experiences in their own words (Atkinson, 2011). The interviews were recorded and filmed, resulting in more than 130 h of audio and video recordings. Triangulation from the multitude of materials and perspectives helps to cross-validate findings and enhances the internal validity of the case study findings.

Alpine pasture farming in Bad Hindelang, Germany

Case study setting

Bad Hindelang is a rural municipality in the southernmost administrative district (Landkreis) of the German State of Bavaria. In 2022, the municipality had a total population of 5,342, scattered over 6 villages and some smaller hamlets (Bayerisches Landesamt für Statistik, 2022). It has an area of 137 km2, out of which around 80% are protected as landscape and nature conservation areas. The municipal area shares an international border with Tyrol in Austria and covers diverse landscapes and altitude levels, from the river valleys (around 800 m a.s.l.) to Hochvogel peak (2592 m a.s.l.) in the Northern Limestone Alps.

Tourism is the economic mainstay of Bad Hindelang. Due to its topography, many outdoor recreation activities from hiking and mountain-biking in the summer to skiing and other winter sports can be offered. Health tourism is another pillar of local tourism and has a long tradition in some of the villages. Hence, the municipality is an established tourism destination within the well-branded Bavarian holiday region of Allgäu. According to Max Hillmeier, the tourism director of Bad Hindelang, tourism contributes around 80% to the local economy in terms of value added and creates approx. 1,400 jobs (pers. comm.1). Before the COVID-19 pandemic, around 200,000 guests generated about one million guest nights per year. In 2022, the municipality was almost back to pre-pandemic levels, with 198,000 guests and 985,000 guest nights (Markt Bad Hindelang and Bad Hindelang Tourismus, 2023).

Intangible cultural heritage in Bad Hindelang

The “High Alpine Agriculture in Bad Hindelang” was included in Germany’s National Register of intangible cultural heritage as a “Good Safeguarding Practice” in 2016. The inscription refers to the traditional practice of alpine pasture farming, which is common across all countries of the European Alps. As agricultural land in the villages of the steep mountain valleys is naturally limited, this land is primarily used for arable farming and hay-making. Hay is stored as fodder for the winter, when the livestock is kept on the village farms. In the summer, livestock is grazed on upland pastures at varying altitudes to make optimal use of the vegetation. Upland pastures thus serve to extend the fodder base for the livestock, allowing farms to survive despite the limitation of farmland (Bätzing, 2021). While it is assumed that alpine pasture farming has been widely practiced for thousands of years, its connection with dairy farming in the Alps is a more recent phenomenon. In the Allgäu region, cheese-making was introduced in the early 19th century.

The German term Alpe (or Alm, plural: Alpen) does not just refer to the high-altitude grazing areas of the livestock (mostly cattle in Bad Hindelang), but also to the farm buildings and shelters erected on-site to accommodate the staff (“Älpler”) and their agricultural equipment during the annual grazing period from June to mid-September. There are 46 Alpen on the territory of Bad Hindelang, covering 56% of the municipality’s territory and forming the largest contiguous area of pasture lands in the Bavarian Alps. The land is owned by the State, the municipality, cooperatives, or by private individuals or companies. Notwithstanding the land ownership status, livestock management on the pastures typically involves collective practices. For instance, individual farmers may graze their livestock on land owned by a cooperative, or cooperatives collectively hire staff to jointly look after the animals of several farmers during the summer (Marktgemeinde Bad Hindelang, 2018). To preserve the cow’s milk on-site, cheese and butter are produced on so-called Sennalpen during the summer (Boeckler and Lindner, 2002; Eberl Medien, 2014; Bätzing, 2021). The term Galtalpen refers to a more frequent variety of alpine pastures, which are exclusively used for the summer grazing of young cattle, therefore involving less labour (German Commission for UNESCO, 2023).

Reacting to the dwindling number of farms and rapid loss of alpine pastures since the second half of the 20th century, the Bavarian State, along with conservationists, started to offer ecological compensation payments for farmers willing to shift to organic farming in the late 1980s. While the offer was made to all farming communities in the Allgäu region, only the farmers of Bad Hindelang initially took up the idea in 1988 (Lindner, 2000). In order to be eligible for the compensation scheme, the farmers formed an association for the conservation of nature, culture and landscape in 1992 (“Hindelang Natur & Kultur—Verein für Landschaftserhaltung e.V.”). Since then, Bad Hindelang farmers have been cultivating not just the high alpine pastures but also the small farms in the valleys according to strict principles of organic farming. This approach has become known as the so-called “eco-model Hindelang” (“Ökomodell Hindelang”).

The heritage community of Bad Hindelang

The practice of alpine pasture farming is still commonly found throughout the Alps and in other mountainous regions of the world (Bätzing, 2021). The focus here is limited to the special case of the heritage community of Bad Hindelang, whose success in safeguarding alpine pasture management was acknowledged by the German Commission for UNESCO with the inclusion in the national inventory of intangible cultural heritage. The actual bearers of this heritage are, primarily, the 61 active members of the farmers’ association “Hindelang Natur & Kultur e.V.” and their families. Due to the large spatial extent of alpine pastures, the shared cultural identity and the dependence on tourism, most residents are directly or indirectly involved in farming, tourism, or even both sectors. It thus seems appropriate to regard the total resident population as the heritage community of Bad Hindelang, which geographically coincides with the municipal area.

Value creation from intangible cultural heritage

Alpine pasture management in Bad Hindelang creates value for the heritage community in several regards. Economic value can be linked to agriculture and tourism. In Bad Hindelang, most farming members of the association complement their income from other business activities or wage employment of other household members, e.g., in tourism, craft or trade. Here as in other parts of the Bavarian Alps, agricultural support schemes enhance the profitability of the farms and secure their survival, as the income from selling dairy products, livestock and meat alone would not be sufficient for the farms to survive (Wanner et al., 2021). According to interviews conducted with two executive members of the farmers’ association, it is only due to the ecological compensation payments that farms still operate in a profitable manner. While the decline of small farms could not be stopped completely since the formation of the association, it is taking place at a much slower pace as compared to other parts of Bavaria, as stressed by the current chair of the farmers’ association. Meanwhile, the founding members of the association have passed on their skills and knowledge to the next generation, safeguarding not just the traditional way of alpine pasture management with its ecological functions but also the cultural practices and regional identity attached to it (German Commission for UNESCO, 2023).

Apart from agriculture, the heritage community also derives direct economic benefits from tourism. Despite the fact that alpine pastures are not natural but “cultural landscapes,” they are of high aesthetic quality and create experiential value for tourism (Figure 2). Fourteen of the 46 Alpen cater to outdoor tourists on-site, operating seasonal restaurants that sell drinks and home-made food (Marktgemeinde Bad Hindelang, 2018). High-quality food such as cheese and butter is produced and processed on the Sennalpen and sold directly to tourists on-site or to local shops, hotels and restaurants in Bad Hindelang (Figure 3). Ten Alpen are members of “Allgäuer Alpgenuss,” a cooperative brand and association of 72 Alpen across the whole Allgäu region with a concession to sell regional food and drinks (Allgäuer Alpgenuss e.V, 2023; Figure 4). Some farmers offer lodging for tourists, either simple accommodation on the pastures, or holiday flats in their village homes.

FIGURE 2

Alpine cultural landscape in the Allgäu mountains, Germany (source: authors’ photo).

FIGURE 3

A Sennalpe (cheese-producing alpine farm) that also caters to hiking tourists in the Allgäu mountains, Germany (source: authors’ photo).

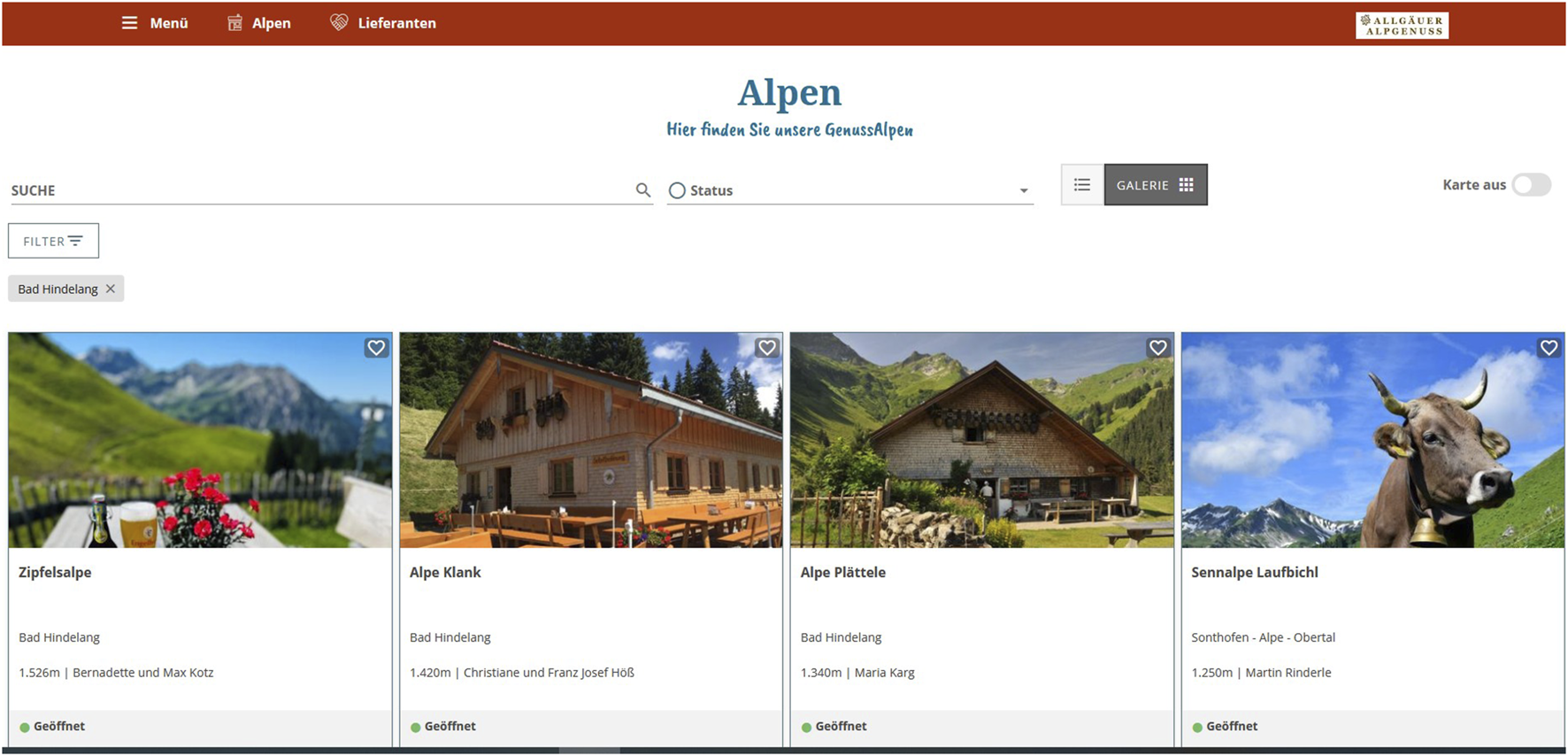

FIGURE 4

Screenshot from the website of “Alpgenuss”, a cooperative regional brand of Alpine farmers in the Allgäu mountains to promote organically produced food (source: Allgäuer Alpgenuss e.V, 2023, https://www.alpgenuss.de/, last accessed 26 July 2023).

Alpine pasture management fulfils important ecological functions, thus creating environmental value for the heritage community. Livestock grazing keeps the alpine pastures free from encroachment of shrubs and trees and considerably enhances biodiversity (Lorenz-Munkler, 2020). In addition, the farmers commit themselves to adhere to the principles of ecological farming under the guidelines of the association. These include restrictions with regard to stocking density, use of fertiliser and pesticides and fodder purchases. It is in recognition of the extra labour and the contribution to landscape protection that the farmers receive the ecological compensation payments from the state and the municipality.

It appears difficult to separate the social and cultural value related to alpine pasture farming, which has shaped the regional identity and lifestyle of the residents in Bad Hindelang and elsewhere in the Alps for centuries. Arguably, the intangible cultural heritage plays an important role in residents’ daily lives. As of August 2023, the municipality lists 87 formally registered local associations (Vereine; Markt Bad Hindelang, 2023b). These associations cater to a range of communal purposes, activities and interests which require collective action. Some associations are related to agriculture, forestry, hunting, fisheries, mountain rescue and fire services. Others deal with tourism, sports, culture (music and theatre groups, organisation of festivals) and other aspects of social life, such as religious, educational or political organisations. Residents’ voluntary engagement in such a large number of community-based organisations indicates a strong social cohesion, place identity and sense of belonging. As noted by the interviewed farmers, the eco-model has improved their social recognition in the community. Non-farming residents realise that the farmers’ hard work preserves not just the ecological and aesthetic value of the alpine landscape but is also immensely important for tourism and the local quality of life (Lindner, 2000).

The cultural identity of the heritage community was highlighted in a strategic development process that the municipality launched in 2019. The community development strategy “Our Bad Hindelang 2030” was conceptualised as a multi-sectoral “living space concept” with an integrated tourism strategy. It shall guide any community projects and political decisions in the coming years, taking into account the various needs, concerns and interests of different economic sectors and stakeholder groups. The intensive public participation and consultation process started with a survey, in which 3,500 local residents and guests participated. Thereafter, 200 residents designed concrete strategies for the development of the community, in line with sustainability principles. This innovative process resulted in the establishment of a new community brand, which is based on people’s commonly shared values. These values were circumscribed with attributes such as contemplative, original, headstrong and open-hearted, and summarised in the phrase “where the soul of the Alps is at home” (translated from German). Ecological sustainability, a strong sense of community, a “living” cultural heritage, quality and innovativeness were highlighted as important principles for future developments in the public participation process (Markt Bad Hindelang, 2023a).

Following the inception of the eco-model, tourism marketing since the 1990s has focused on promoting a low-impact, sustainable tourism that attracts families and rather demanding, nature-loving tourists that appreciate a high-quality tourism offer in a healthy, scenic mountain environment (Lindner, 2000). Apart from general restrictions such as shortage of labour, tourism development has been relatively stable in the past decade, with a good average occupancy and a rapid recovery after the COVID-19 pandemic (Markt Bad Hindelang and Bad Hindelang Tourismus, 2023). The focus on environmental sustainability, cultural values and quality is also reflected in the new tourism development and marketing strategy that was developed on the basis of the living space concept. The eco-model and the sustainable tradition of alpine pasture management are highlighted as part of the local lifestyle that residents are willing to share with the guests (Markt Bad Hindelang and Bad Hindelang Tourismus, 2023). The guest card “Hindelang Plus” includes various benefits for overnight visitors such as free public transport, use of cable cars and ski lifts and a range of “local experiences.” The latter offer authentic experiences accompanied by local guides, e.g., sunrise hikes, cooking classes or tree-planting with a forester.

Case study summary

As shown above, alpine pasture farming is part of a cultural ecosystem and lifestyle that is of significant economic, ecological, social and cultural value not just for farming households but for the whole heritage community of Bad Hindelang. This is expressed in the shared values derived from the past that give direction to current and future developments in the fields of agriculture, tourism and landscape protection. Mutual benefit is derived from an enhanced destination image and a competitive tourism offer with a unique appeal, based on the traditions, products and the lifestyle of the mountain farmers. The farmers’ decision to collectively commit themselves to organic farming and maintaining the alpine pastures, as promoted by the eco-model Bad Hindelang, has proven sustainably successful in consolidating the number of farms and preserving the biodiversity and recreational value of the alpine landscape. The acknowledgement of the “High Alpine Agriculture in Bad Hindelang” in Germany’s register of intangible cultural heritage also promoted its scientific documentation and preservation for future generations. Meanwhile, several books have portrayed the 46 Alpen and the hard work and life style of the farmers as well as the culinary heritage of the region (Eberl Medien, 2014; Marktgemeinde Bad Hindelang, 2018; Marktgemeinde Bad Hindelang, 2022).

Marche food and wine memories, Italy

Case study setting

The Marche Food and Wine Memories project is located in and around Offida, a rural municipality (commune) with 4,693 inhabitants in the south of Le Marche Region in central Italy. The municipal territory covers 49.6 km2, most of which belong to the rural areas surrounding the historical town centre. They represent the typical landscape of Le Marche with rolling hills, vineyards, olive groves, wheat fields, farms and traditional rural houses. The village is situated approximately 20 km from the coastline of the Adriatic Sea and around 45 km from the mountains of Monti Sibillini National Park. Offida is located within the Tronto River basin at an elevation of roughly 293 m above sea level.

The village and rural surroundings suffered from a series of economic and social challenges in the last 30 years. The first one was de-industrialisation. Starting from the beginning of the 1990s, the closure process of local industries was essentially due to the termination of government subsidies in the southern Marche provided by the public “Cassa del Mezzogiorno” fund (Ridolfi, 2007). The de-industrialisation process intensified from 2008 to 2013 because of the European economic crisis. The main legacy of this combination of corporate “welfarism” and de-industrialisation is a lack of local entrepreneurial spirit and skills (Unione Europea, Regione Marche, 2014). The second challenge was de-population. Like other rural territories in Italy and other European countries, the inner peripheries of Le Marche have suffered from industrialisation and the competition of urban development (ISTAT, 2020). Cities are better connected and offer more opportunities in terms of jobs and services, which is especially appealing to the young generation. The depopulation trend intensified after 2016 and 2017 because of a series of earthquakes in central Italy, which also affected the southern Marche region. De-industrialisation and de-population put the rural areas of the southern Marche region into a fragile position. The combination of an economy largely consisting of family-run SMEs and micro-companies (especially in the agricultural sector), an aging population and the lack of a skilled workforce—due to the rural exodus and brain drain towards the northern regions of Italy and other countries—make it difficult to find local resources for reversing these negative trends.

More recently, tourism promises to leverage regional rural development in Le Marche. With an unprecedented 2.5 million arrivals and 11.3 million guest nights, 2022 was a historic year for tourism in Le Marche, surpassing even pre-pandemic levels. While the majority of visitors of Le Marche are Italian nationals from nearby regions, a noticeable and above-average increase of foreign visitors was recently observed with 399,173 arrivals (16% of total arrivals, up by 69% as compared to 2021) and 1.7 million guest nights (15% of total guest nights, up by 66% from 2021). The main nationalities contributing to this growth include Germany, the Netherlands, Switzerland, France, and Belgium. Rising numbers of tourists are also recently reported from Britain and Poland (Regione Marche, 2023; Regione Marche, Ufficio di Statistica, 2023).

Offida is part of the Italian association “I Borghi più belli d’Italia” (English: the most beautiful villages of Italy) that aims at promoting small rural towns of historical and artistic interest that are typically located “off the beaten track” of popular tourist itineraries (Figure 5). For all 20 Italian regions, the association’s website lists 313 villages, among which 29 are located in Le Marche. The member villages are described as “fascinating small Italian town[s], generally fortified and dating back to the period from the Middle Ages to the Renaissance,” usually rising around castles or noble palaces and often surrounded by defensive walls and towers (I Borghi più belli d’Italia, 2023).

FIGURE 5

Townscape of Offida, Italy (source: authors’ photo).

Intangible cultural heritage of Le Marche

The community of Offida and the surrounding rural areas share the common legacy of the Mezzadria (sharecropping) system. The Italian term derives from Latin, meaning “divided in two-halves”. Mezzadria refers to a contractual arrangement between a landowner and a landless sharecropping family, whereby the landowner gave the sharecropper’s family some land for cultivation and a small house to live in, in exchange for a 50% share of the fruits of their work (especially half of their wheat harvest but also of any livestock, cheese, vegetables and eggs produced by the Mezzadria farm). In Italy, this arrangement started in Tuscany in the ninth century and had spread throughout central Italy until the 14th and 15th centuries (Anselmi, 1995). In the Marche region, Mezzadria was extensively practiced and ended only in the 1980s, following industrial development and the resulting exodus from the countryside. In 1982 the Italian parliament passed a law to transform the remaining sharecropping arrangements into rental contracts (Passaniti, 2017). However, the legacy of the Mezzadria system has had an important socioeconomic and cultural impact in Le Marche in terms of shaping the agricultural landscape, rural architecture, work ethics, craftsmanship and culinary and wine traditions. To gain a full understanding of Le Marche region and its people, which are called marchigiani in Italian, understanding the Mezzadria system thus seems important.

As explained earlier, intangible cultural heritage is conceived as a dynamic, collective and “living” asset that will be transmitted across generations if it is perceived as valuable or part of people’s own identity. The Marche Food and Wine Memories project was initiated by the winery Ciù Ciù, with support from the cultural heritage start-up company i-strategies, both based in Offida. Ciù Ciù winery was founded in 1970 by a former sharecropper who had bought the land he had previously cultivated for a landowner. The project emerged from the desire to save the intangible cultural heritage that is part of the company owner’s family and territory. The family also had an interest to add value to its brand and products “by rediscovering the food and wine roots of our territory,” which are a distinctive aspect of local culture and regional identity (Cerquetti et al., 2022, p. 8). By collecting the oral memories of the last remaining witnesses of sharecropping, the project aims to safeguard and enhance the culinary heritage linked to food and wine in the southern Marche region. The project combines corporate heritage marketing with educational and cultural tourism activities.

Culinary heritage as a concept is usually defined under the umbrella term of food heritage. According to

Béssiere (1998, p. 279), food heritage refers to “agricultural products, ingredients, dishes and cooking artefacts. It also comprises the symbolic dimension of food (table manners, rituals), techniques, recipes, eating practices and food-related behaviours and beliefs.” Starting from the definition of culinary heritage as “elements and practices related to the preparation and consumption of food” (

Timothy and Ron, 2013) the

Marche Food and Wine Memoriesproject has focused on four elements of the local culinary heritage:

• Culinary heritage recipes: Culinary heritage recipes refer, strictu sensu, to the cooking process of food in terms of ingredient lists to use, ways to prepare it, cooking accoutrements, instruments, practices, know-how and recipes;

• Culinary heritage identity: Culinary heritage identity belongs to the symbolic and emotional dimension of food. Food contributes to defining ourselves, our communities and our intersubjective relations with other groups. In this definition, the ethnic, national, political and local dimensions of food are included;

• Culinary heritage habits: Culinary heritage habits evoke eating traditions, regular eating practices, and the role cultural and social influences have on food traditions. It also includes how people eat and why they choose a certain food instead of another one;

• Culinary heritage sociability: Culinary heritage sociability alludes to how food fluidifies, favours, includes or excludes, and, more generally, conditions social relations. It also allows us to understand why we choose to eat with certain people and why we prefer not to eat with others.

The heritage community of Offida

Following the definition provided by the

Council of Europe (2005), a heritage community is distinguished by awareness of the cultural heritage and a sense of belonging. The heritage community of Offida, defined as the population of the rural town and its surrounding area, has preserved at least five different types of cultural activities, which have been transmitted over the generations

2‐ 5:

• Rural art and culture festivals: these local festivals usually have two formats. They can be historical reenactments of ancient rural practices like wheat threshing like the “Rievocazioni della Trebbiatura” (English: reenactments of threshing). The second festival format relates to modern representations of the rural heritage in the form of music festivals, theatre and art performances. A recent example of the latter is the “Appignano del Tronto Rural Art Festival.” Supported by the European Union, this festival is part of a pilot project to promote rural regeneration based on cultural and natural heritage.

• Rural sagre: Sagre are short open-air culinary festivals that usually take place in summer (July and August). Each sagra is dedicated to a specific type of local food, e.g., pasta, meat or fish. People can taste traditional preparations of this food during the sagra days (generally between two and five) in a sociable and relaxing atmosphere. Every village or neighbourhood organises their own sagra. The community of Offida organises the sagra dei taccù, the latter referring to the traditional pasta made from flour and water that was typically consumed by sharecropping families in the past.

• Rural museums: In the Marche region, there are numerous rural museums that collect and share information and objects about the region’s rural past and ancient practices. The most important museum relating to the cultural heritage of sharecropping is the “Museo di Storia della mezzadria Sergio Anselmi” based in Senigallia, Ancona province. In Offida, there is another rural museum, the “Museo delle tradizioni popolari.”

• Rural craftsmanship courses: Rural craftsmanship courses are organised by local non-profit and cultural associations to transfer traditional craftsmanship skills related to the sharecropping civilisation to the younger generation. In Offida, a popular course to create handmade wicker baskets is organised annually by the local “Associazione Culturale Offida Nova.”

• Rural dances and music: Rural Italy is rich in traditional music and dances. In the Marche region, the accordion (Italian: fisarmonica) is recognised as part of the local identity with an internationally recognised museum in Castelfidardo. The typical traditional dance Saltarello is spread through an informal network of local associations and transmitted via courses and dance festivals.

Value creation from intangible cultural heritage

The intangible cultural heritage promoted by the Marche Food and Wine Memories project has created significant social value for the heritage community of Offida and elsewhere in the countryside of the southern Marche region, which is still affected by the economic transformation processes of the recent past. Perhaps most importantly, the narrative interviews with the former sharecroppers have promoted social inclusion. Because almost all of the sharecroppers were illiterate, narrating their life stories orally was the only way for them to adequately express themselves. Becoming the protagonists of the interviews let them realise the relevance of their personal life stories. This challenged the sense of inferiority that they, as rural peasants, had always felt. Furthermore, the interviewees often experienced a new sense of dignity related to their rural past and felt happy to express their personal feelings during the interviews. The project also promoted intergenerational dialogue and social cohesion, especially when grandchildren of the former sharecroppers took part in the interviews. In many instances, young adults thus discovered their own family background for the first time. Getting to know their ancestors’ life stories and interacting with their grandparents during the interviews resulted in an intense emotional experience. The project thus promotes people’s regional identity and sense of belonging.

Apart from social value, the recorded interviews also have an intrinsic cultural value. The sharecroppers’ oral memories are a rich source of information on ancient agricultural practices and life styles that have influenced the heritage community of the southern Marche region until today. The recorded interview material is safeguarding this heritage before people pass away and their memories get lost forever. The key technique used for the dissemination of the sharecroppers’ oral memories and cultural heritage marketing is storytelling. Hence, after transcription, stories linked to the local history, identity and traditions, values and feelings were selected for further use in storytelling online and onsite (Cerquetti et al., 2022). The interviews also present a unique historical archive of the regional heritage that can be made accessible to researchers and scholars. During the phase of interview recording, the sharecroppers’ food and wine memories were shared on a Facebook page.6 The local community reacted through posts expressing interest, nostalgia and pride in their rural past. Especially people with a family background in sharecropping started reclaiming their rural identity, values and origins. As a result, the grandchildren of former sharecroppers frequently send messages asking to interview their grandparents.

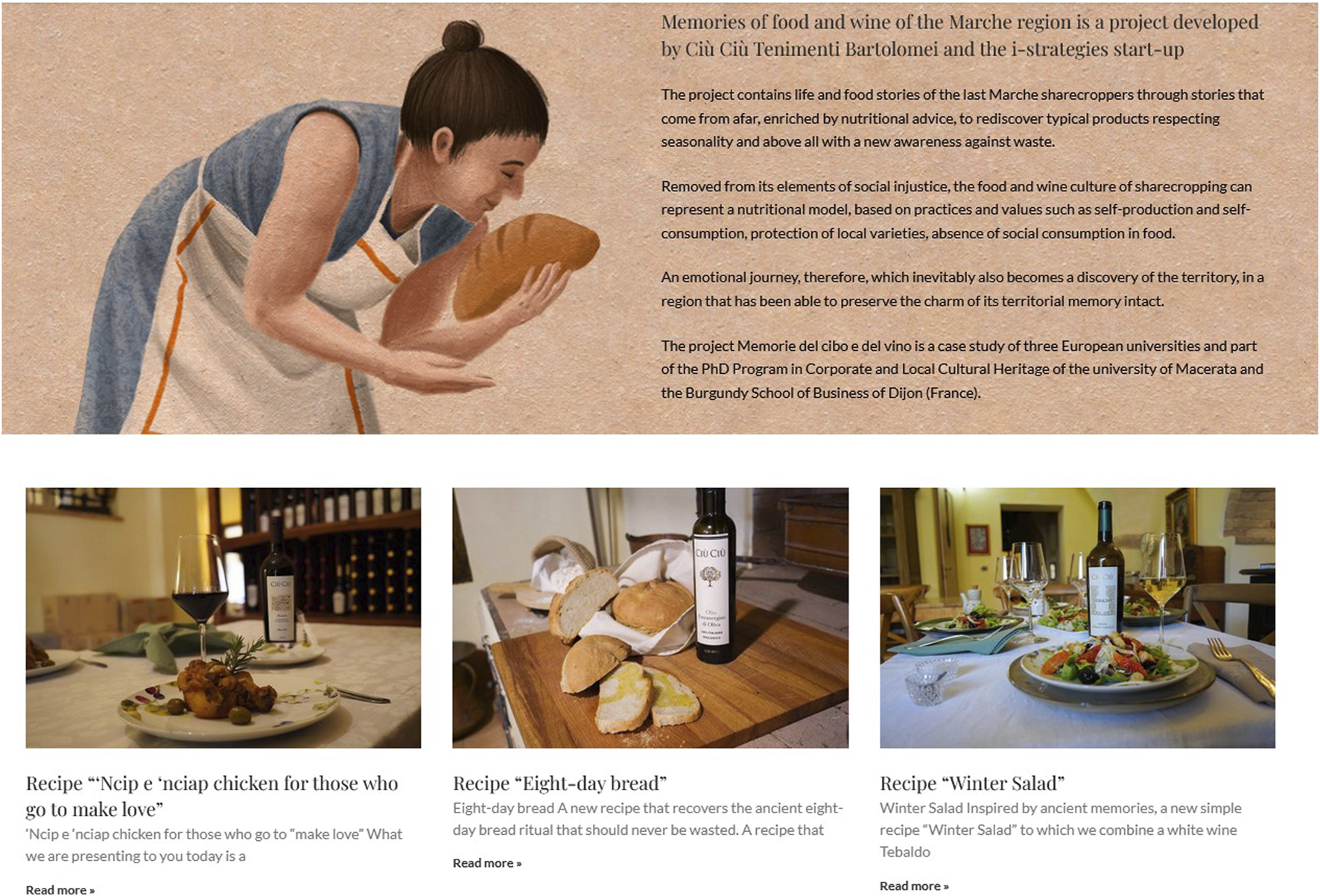

One specific outcome of the project is the collection of traditional recipes based on the interview material. These were developed into “food stories,” which highlight anthropologically interesting aspects of the culinary heritage. A professional cook, inspired by the oral memories, recreated and adapted the sharecroppers’ ancient family recipes, paying attention to authenticity and sustainability. The names of the recipes are not descriptive but evocative, named after the feelings that people used to have toward certain dishes (e.g., “Desired Saint Antonio sausage,” “Tedious tagliolini,” “‘Ncip e ‘nciap chicken for those who go to make love”). Using digital storytelling, 40 short videos were produced, of which 30 have already been published on the corporate website and social media pages of the Ciù Ciù wine company and thus made accessible to a wider audience in Italian and English (Figure 6). Each video is presented with a short description, the recipe and a matching wine recommendation (Ciù Ciù Tenimenti Bartolomei, 2023). As mentioned above, one initial aim of the project was the creation of economic value for the winery, which is difficult to quantify at present. The company’s activities could serve as a benchmark for other companies in the region intending to invest in cultural heritage marketing. “[T]he local and corporate cultural heritage can be a marketing lever for ‘Made in’ companies, especially those operating in the food and wine sector.” In increasingly global markets, corporate heritage marketing in a specific territorial context could therefore create a competitive advantage for companies (Cerquetti et al., 2022, p. 8). In recognition of their engagement in cultural heritage promotion via the Marche Food and Wine Memories project, Ciù Ciù Winery was shortlisted in 2022 for Italy’s Corporate Heritage Awards.7

FIGURE 6

Food and wine storytelling on the website of Ciù Ciù wine company in Offida, Italy (source: Ciù Ciù Tenimenti Bartolomei, 2023. Ancient recipes. Memories of food and wine of the Marche region, https://www.ciuciutenimenti.com/ancient-recipes, last accessed: 15 September 2023).

Economic value beyond the level of single companies could be derived in the future from cultural and culinary tourism. As compared to other Italian regions such as Lazio, Veneto or Tuscany with their long history as popular tourist destinations, Le Marche arguably still has potential for further growing tourism. The region has been described as “Italy in one region” or “Italy off the beaten path” and offers a wide range of cultural attractions and scenic landscapes. Tourism could contribute to regional rural development in Le Marche and thus help to overcome the economic challenges of the region that were described above. However, the rural countryside of Le Marche is currently lacking tourism-related infrastructure, promotional activities and effective place branding particularly for the international market.

In 2018, i-strategies started to organise guided and gamified tours to typical sharecroppers’ houses in the rural countryside of Acquaviva Picena, near Offida. Both tour formats use educational storytelling to explain the agricultural history of the Marche region through the voices and faces of those who were part of the territory’s heritage (Cerquetti et al., 2022). The gamified tour format was developed through an EU-funded heritage marketing project8 and successfully tested with several international student groups on-site.9 The game, named Pantafga after a legendary creature in the local folklore, is organised as a team competition. After reading non-fiction stories based on the former sharecroppers’ memories who lived in the locality where the game takes place, the teams have to discuss and find the correct answers to questions related to the stories (Vagnarelli, 2022; Figure 7). The guided and gamified tours conclude with a tasting of local wines at the showroom of Ciù Ciù winery in Offida, or with another culinary experience. Positive feedback from these pilot activities underlines the experiential value for domestic and international visitors that could be utilised for the development of innovative package tours that involve authentic cultural heritage experiences for tourists (Cerquetti et al., 2022). Storytelling, the key method applied both in corporate heritage marketing and the pilot tourism activities, seems particularly promising to actively and emotionally engage tourists.

FIGURE 7

The agricultural landscape of Le Marche, Italy provides an attractive setting for visitors to explore and learn about the area’s intangible heritage during a gamified tour (source: authors’ photo).

Case study summary

The Marche Food and Wine Memories project presents an unusual combination of heritage marketing and cultural tourism activities by leveraging the agricultural and culinary heritage in a specific rural territory. The project’s outputs to date, including the audio and video material based on the oral memories of former sharecroppers and the production of 40 videos, have created considerable social and cultural value for the residents of the southern Marche region. Since 2018, around 600 visitors, about half of them international tourists and university students, experienced the intangible cultural heritage of the southern Marche region during a guided or gamified tour of the rural countryside near Offida.10 While this figure is not impressive, the innovative practices piloted by the project at the corporate and community level have the potential to be further scaled up.

At the corporate level, the project has started to demonstrate the potential of cultural heritage marketing. It is expected that it will create value for the company’s own brand and products, but it also presents an innovative approach to safeguard and promote the territorial heritage with support from the private sector. Arguably, cultural heritage cannot be sustainably developed and safeguarded with public sector funding alone. As regards the heritage community of Offida and the surrounding countryside, the project contributed to rural regeneration and social cohesion. Besides its focus on the intangible heritage through storytelling, the project also contributed to a regeneration of physical assets, such as reconstruction or renovation of abandoned farm buildings, such as the typical sharecroppers’ houses. Moreover, the visits of tourists and students with interest in the Marche region’s rural history and cultural identity could serve as a model for a regenerative, low impact and sustainable tourism development in the region. Social cohesion among the heritage community has been strengthened by sharing oral memories through storytelling, thus reversing negative feelings about a painful past. The former sharecroppers and their descendants can now reconsider their history with a new sense of dignity based on their culinary heritage, resulting in the promise of a more sustainable rural future.

Discussion of case study Results

The intangible cultural assets held by the heritage communities of Bad Hindelang (Germany) and Le Marche (Italy) are each quite distinct, demonstrating the broad scope and context-dependency of cultural heritage. Nonetheless, the two case studies also share a range of commonalities. Both are located in rural areas of the respective countries, both deal with traditional agricultural practices and both are closely connected to the territory’s historical legacy. As regards the German case study, the sustained practice of alpine pasture farming has preserved the cultural landscape and its recreational value for tourism over several generations. In the Italian case, the archaic practice of sharecropping, which used to be linked to a poor class of rural peasants, has continued up until late in the 20th century before it finally disappeared. However, the rural peasant’s culinary heritage was safeguarded and transmitted into the presence through a cultural heritage project. The project could further promote culture-based tourism experiences, such as the pilot tours organised by the start-up company in cooperation with the wine company. Both case studies show how intangible heritage assets can contribute to sustainable rural development, if “use value” is created for local communities. Table 1 provides a summary of the main research findings.

TABLE 1

| Variable | Bad Hindelang, Germany | Le Marche, Italy |

|---|---|---|

| Intangible cultural heritage assets | Farming and cultural practices related to alpine pasture management | Collection of oral memories of former Mezzadria sharecroppers; culinary heritage |

| Heritage community | Bad Hindelang municipality (six villages and alpine pastures) | Offida and surrounding rural areas of southern Marche region |

| Economic value | From farming and outdoor tourism (hiking, skiing, mountain-biking) | Corporate heritage marketing; potential for cultural tourism based on “Marche Food and Wine Memories” |

| Social value | Acknowledgement of farmers’ contribution to landscape protection; social cohesion (e.g., organisation of festivals relevant for tourism) | Social cohesion, social inclusion, intergenerational dialogue; appreciation of culinary traditions; educational value |

| Cultural value | Preservation of cultural traditions connected with alpine pasture management (e.g., “Viehscheid”) | Historical archive of Mezzadria legacy; preservation of culinary heritage (e.g., ancient recipes) |

| Environmental value | Preservation of biodiversity and cultural landscape | Preservation of rural dwellings (former sharecroppers’ homes) |

| Experiential value (for visitors) | Preservation of “idyllic” mountain scenery for outdoor tourism and sports; participation in rural festivals; encounters with locals through guided experiences; high-quality local food | Guided and gamified tours to explore the history and life stories of former sharecroppers in the rural countryside; high-quality local food and wine |

Overview of case study findings.

Source: own compilation.

As regards the economic valorisation of cultural heritage through tourism development, the two case studies represent opposite stages of the destination life cycle (Butler, 2011). Bad Hindelang, a popular resort for outdoor and health tourism in the Allgäu region of the Bavarian Alps, has reached maturity in the destination life cycle. With an early focus on sustainable tourism and innovation, the destination has mastered a constant rejuvenation even beyond the COVID-19 pandemic. The foundation for such a continued, successful tourism development was laid almost four decades ago through an innovative alliance of local farmers and conservationists that was forged via the eco-model. The survival of the small mountain farms has preserved the cultural landscape, the life-style and the cultural heritage associated with alpine pasture farming. All these elements are equally important for tourism. Since the inception of the eco-model, tourism in Bad Hindelang has developed sustainably—not antagonistically—alongside farming, nature conservation and protection of the cultural landscape. As elsewhere, land use conflicts between tourism, conservation and traditional economic activities such as farming, forestry and hunting continue to exist. It seems that the heritage community is able, however, to resolve such conflicts based on a joint agenda that was first initiated by the local farmers’ association and reaffirmed in 2019 during the participatory development process for a new strategic plan for the municipality. Today, tourism plays a dominant role in the local economy. With a focus on quality rather than merely quantitative growth this is not opposed to the objectives of alpine pasture farming and nature conservation. Visitors benefit from the recreational value of the alpine landscape and enjoy authentic cultural experiences and encounters with locals. A vivid illustration of this is the annual “Viehscheid,” as the traditional Alpine cattle drive at the end of the grazing period is called in Bad Hindelang. While the festive cattle descent and separation of herds in the villages has certainly become a major tourist attraction, it is deeply rooted in the local heritage and a major social event for the whole community. Without collective action and social cohesion, such institutions would not have survived or lost their authentic appeal and, hence, become less attractive for visitors.

The southern Marche region is yet to be discovered by domestic and international tourism as a destination, as compared to more popular tourist regions in central Italy, such as Tuscany. Located between the contrasting landscapes of the Adriatic coast and the Sibillini mountains and surrounded by rolling farmland and vineyards, Offida and the southern Marche region are equally rich in cultural attractions. The region thus appears well-positioned for tourism development but is yet to leverage this potential. The Marche food and wine memories project has preserved the oral memories of the region’s last surviving Mezzadria (sharecropping) farmers—a heritage that otherwise would have been lost forever for coming generations. The social and cultural importance of the project for the heritage community is evident, as has been discussed above. However, economic value from the project has so far been very limited (cf. Cerquetti et al., 2022 for a detailed discussion). Feedback from domestic and international visitors who attended a guided or gamified tour organised by the start-up company was overwhelmingly positive. Such tours could be made available to a wider public, if suitable tourism industry partners are found, including tour operators specialising in novel cultural tourism offers. Arguably, in the aftermath of the COVID-19 pandemic, increasing demand for less known, less crowded and more authentic tourism destinations can be expected, offering an opportunity to scale up the activities pioneered by the project to expand the tourism offer of the southern Marche region (Cerquetti et al., 2022).

Conclusion and perspectives

Cultural diversity can enhance people’s quality of life and form a counterweight to an increasingly uniform “world society” shaped by just a few political superpowers and global companies. As demonstrated by the two case studies, it does not necessarily require “exceptional” forms of material culture, such as world-famous monuments, museums and paintings, to create value for heritage communities. Through innovative approaches that use storytelling and engage stakeholders in a participatory manner, even less spectacular, “commonplace” expressions of the intangible culture could be made accessible to a wider public and benefit heritage communities in a variety of ways.

Innovation has played an important role in both case studies presented. When Bad Hindelang farmers teamed up with nature conservationists and adopted the ecological principles of the eco-model, they met with scepticism and disbelief by farmers from neighbouring villages. Only more recently have farming communities in other parts of the region followed suit, copying the approach of the eco-model. For the local farmers, the transition to ecological farming resulted in a more favourable income situation, thus explaining the survival and intergenerational transmission of alpine farms. But, as illustrated by one of the young-generation members of the association, the financial incentive of ecological compensation payments only partly explains this success:

“Many of the farmers in Bad Hindelang are idealists, for whom financial aspects often are not in the foreground. Instead, it is the joy, passion, and close connection to traditional agriculture, as it is still practiced in Bad Hindelang to this day. […] Furthermore, it's not only the farmers […] who have a very close bond with their region, nature, and local culture, but also many of the citizens of Bad Hindelang, and naturally, the municipality of Bad Hindelang itself. This, along with the high appreciation shown to the farmers here, is what underpins the success of the eco-model: it is embraced and supported by all parties involved.”

As supported by this quote, a key factor of success for the eco-model Bad Hindelang was the collaboration between the farmers and the local community, including tourism stakeholders. The municipality has played a particularly important role in facilitating communication among all stakeholder groups and creating a common vision and common local identity as a basis for future development. Further expanding the eco-model and safeguarding the practice of alpine pasture farming across international boundaries throughout the Alpine region seems desirable to maintain biodiversity and resilience in fragile mountain landscapes. In the Alps, these are under increasing pressure not just from tourism and forest encroachment but also due to global climate change (Kotlarski et al., 2023).

In the Marche region, a wine company’s own family background sparked interest in preserving the oral memories of the last sharecroppers. While this land tenure arrangement had disappeared until the 1980s, its legacy has persisted in the region until today. Oral memories of the last sharecroppers resulted in the rediscovery of ancient recipes and inspired digital storytelling based on the local culinary heritage. Storytelling is also used during the guided and gamified tours in the rural places where those stories occurred, and this is successful to actively engage the tour participants. As highlighted by Cerquetti et al. (2022), the Marche Food and Wine Memories project has been successfully preserving the cultural heritage of former sharecroppers so far but yet has to be fully adopted and exploited by the heritage community. Collaboration and networks across sectors as well as better communication between stakeholders is necessary, as underlined by the successful example of Bad Hindelang.

In Bad Hindelang, storytelling has also been practiced. Through short interviews in the latest guest magazine, prospective visitors get to know local people, such as an alpine farmer, a hotel owner, a mountain guide and a cook, even before their arrival. Recently, a picture book was published that intertwines traditional recipes from elderly village women with their life stories (Marktgemeinde Bad Hindelang, 2022). This approach is similar to the Marche food and wine memories, but a different format was chosen. Whereas the wine company in Italy uses digital storytelling, a printed book was the medium of choice in the Bad Hindelang case. In a globalised and increasingly digital world economy, storytelling appears as an adequate tool to create and promote a novel “ecosystem of hospitality” (Philipp et al., 2022). As demonstrated by both case studies, storytelling seems particularly promising for the valorisation of intangible heritage. However, further research in this area is needed, including an assessment of the effectiveness of storytelling in different contexts, in reaching different target groups and with different formats.

Concluding from the two case studies, intangible cultural heritage can contribute significantly to sustainable rural development and people’s quality of life due to creation of economic, social, cultural and environmental value. Such heritage assets are inevitably place-specific. They do not need to represent “spectacular” forms of cultural heritage with a universal value for humanity, such as the heritage assets protected under the 1972 UNESCO world heritage convention. Intangible cultural heritage, instead, serves other purposes. It can help to restore dignity to a heritage that a community does not feel comfortable about, as in the case of the Marche Food and Wine Memories project. It may also fulfil other important functions with benefits beyond the local level, such as maintaining a landscape’s aesthetic value and ecological integrity, as in the case of Alpine pasture farming. Both case studies illustrate that economic practices are always embedded in a particular ecological and social context and go well beyond just fulfilling material needs. Many other facets and variations of intangible heritage assets exist and could potentially create value for heritage communities world-wide, particularly in developing countries. Corporate heritage marketing, sustainable rural farming and tourism development were shown in this article as possible avenues for value creation. The Bad Hindelang example demonstrates the importance of cross-sectoral collaborations and involvement of different stakeholder groups, which has not yet occurred in the case of Le Marche. In any case, unearthening the treasure of intangible cultural heritage requires a thorough understanding of the locality and an empathetic, participatory approach.

Evidently, the case study approach chosen for this contribution comes with some limitations due to their illustrative character and the diverse range of aspects covered. A more rigorous, quantitative study is recommended to reveal and monitor the specific value of cultural heritage in a particular geographical setting, e.g., number of jobs created, development of income or company turnover. However, it was the intention of this article to present and compare two good-practice cases in their real-world setting to highlight the role of innovation and creativity in developing intangible culture heritage assets for sustainable development, including opportunities for tourism and other businesses. These examples can be used as a starting point to search for and develop “commonplace” cultural assets in (potential) tourism destinations elsewhere.

Statements

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

MS has contributed the introduction, methodology, conceptual framework, case study on Bad Hindelang and the discussion of results. GV has contributed the case study on Offida, with complementary input from MS, and made additions to the other sections. Both authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of interest

Author GV was employed by the company i-Strateges scarl.

The remaining author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Footnotes

1.^Information derived from personal communications and interviews with local experts and stakeholders is marked with “pers. comm.”

2.^Cf. the webpage of the Ruritage project: https://www.ruritage.eu/replicators/marche-region/

3.^Museum website: https://www.feelsenigallia.it/da-vedere/musei/museo-storia-mezzadria-sergio-anselmi.html, last accessed: 21 August 2023.

4.^Museum website: https://www.museionline.info/musei/museo-delle-tradizioni-popolari-di-offida, last accessed: 21 August 2023.

5.^Museo della Fisarmonica, https://www.museodellafisarmonica.it, last accessed: 21 August 2023.

6.^ https://www.facebook.com/memoriedelciboedelvino/

7.^ https://www.corporateheritageawards.it/

8.^Heritage Marketing for competitiveness of Europe in the global market, https://marher.eu/, last accessed: 21 August 2023.

9.^Cf. the videos produced during the activities on the i-strategy YouTube channel: https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCJK6vFblIXxxELvkcE-Gnmg, last accessed: 21 August 2023.

10.^Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, no tours could be conducted in 2020 and 2021.

References

1

Allgäuer Alpgenuss e.V (2023). Allgäuer Alpgenuss Hier schmeckt’s guat. Available at: https://www.alpgenuss.de/ (Accessed June 08, 2023).

2

Anselmi S. (1995). Contadini marchigiani del primo Ottocento Una inchiesta del Regno Italico. Senigallia: Edizioni Sapere Nuovo.

3

Atkinson R. (2011). The life story interview. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications.

4

Bätzing W. (2015). Die Alpen. Geschichte und Zukunft einer europäischen Kulturlandschaft. Fourth, revised edition. Munich: C.H. Beck.

5

Bätzing W. (2021). Alm-und Alpwirtschaft im Alpenraum Eine interdisziplinäre und internationale Bibliographie. Augsburg, Nürnberg: Context.

6

Bayerisches Landesamt für Statistik (2022). Bevölkerung: Gemeinden, Stichtage. Available at: https://www.statistikdaten.bayern.de/genesis/online#astructure (Accessed February 08, 2023).

7

Bessière J. (1998). Local development and heritage: traditional food and cuisine as tourist attractions in rural areas. Sociol. Rural.38 (1), 21–34. 10.1111/1467-9523.00061

8

Boeckler M. Lindner P. (2002). Alpen: Allgäu—Regionalisierungen und struktureller Wandel in Landwirtschaft und Tourismus. Petermanns Geogr. Mittl.146 (6), 38–43.

9

Borin E. Juno-Delgado E. (2018). The value of cultural and regional identity: an exploratory study of the viewpoints of funders and cultural and creative entrepreneurs. Eur. J. Cult. Manag. Policy8 (1), 16–29. 10.3389/ejcmp.2023.v8iss1-article-2

10

Butler R. W. (2011). Tourism area life cycle. Contemporary tourism reviews. Available at: http://www.goodfellowpublishers.com/free_files/fileTALC.pdf (Accessed August 23, 2023).

11

Cameron C. (2023). Evolving heritage conservation practice in the 21st century. Singapore: Springer Nature.

12

Cerquetti M. Ferrara C. Romagnoli A. Vagnarelli G. (2022). Enhancing intangible cultural heritage for sustainable tourism development in rural areas: the case of the “Marche food and wine memories” project (Italy). Sustainability14, 16893. 10.3390/su142416893

13

Cerquetti M. Romagnoli A. (2022). “Towards sustainable innovation in tourism: the role of cultural heritage and heritage communities,” in Cultural leadership in transition tourism: developing innovative and sustainable models. Editor BorinE. (Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing), 33–50.

14

Ciù Ciù Tenimenti Bartolomei (2023). Ancient recipes. Memories of food and wine of the Marche region. Available at: https://www.ciuciutenimenti.com/ancient-recipes/ (Accessed August 18, 2023).

15

Council of Europe (2005). Explanatory report to the Council of Europe framework convention on the value of cultural heritage for society. Faro, Portugal: Council of Europe Report.

16

Demartini P. Marchegiani L. Marchiori M. Schiuma G. (2021). “Connecting the dots: a proposal to Frame the debate around cultural initiatives and sustainable development,” in Cultural initiatives for sustainable development. Editor DemartiniP. (Switzerland: Springer Nature), 1–19.

17

Eberl Medien (2014). Kulturerbe Alpwirtschaft in Bad Hindelang im Naturschutzgebiet Allgäuer Hochalpen Augsburg: context. Available at: https://www.zvab.com/9783939645801/Kulturerbe-Alpwirtschaft-Bad-Hindelang-Naturschutzgebiet-393964580X/plp%26prev=search%26pto=aue.

18

ESPON (2017). Inner peripheries in Europe. Possible development strategies to overcome their marginalising effects. Available at: https://www.espon.eu/sites/default/files/attachments/ESPON-Policy-Brief-Inner-Peripheries.pdf (Accessed July 31, 2023).

19

ESPON (2020). Measuring economic impact of cultural heritage at territorial level—approaches and challenges ESPON EGTC working paper, 20. Available at: https://www.espon.eu/sites/default/files/attachments/Working%20Paper%2C%20Cultural%20heritage.pdf (Accessed July 27, 2023).

20

European Parliament (2015). Towards an integrated approach to cultural heritage for Europe. P8_TA-PROV(2015)0293. European Parliament resolution of 8 September 2015 (2014/2149(INI)).

21

EUROSTAT (2023). GDP per capita, consumption per capita and price level indices EUROSTAT Statistics Explained. Available at: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=GDP_per_capita,_consumption_per_capita_and_price_level_indices (Accessed July 31, 2023).

22

Flyvbjerg B. (2006). Five misunderstandings about case study research. Qual. Inq.12 (2), 219–245. 10.1177/1077800405284363

23

German Commission for UNESCO (2023). Allgaeu’s high alpine agriculture in Bad Hindelang. Available at: https://www.unesco.de/en/culture-and-nature/intangible-cultural-heritage/national-register-good-safeguarding-practices/high (Accessed March 08, 2023).

24

Heritage A. Copithorne J. (2018). “Sharing conservation decisions,” in Current issues and future strategies (Rome: ICCROM).

25

Heritage A. Iwasaki A. Wollentz G. (2023). “Anticipating futures for heritage,” in ICCROM foresight initiative horizon scan study 2021 (Rome: International Centre for the Study of the Preservation and Restoration of Cultural Property ICCROM).

26

I Borghi più belli d’Italia (2023). The Association of the most beautiful villages in Italy. Available at: https://borghipiubelliditalia.it/en/the-club/ (Accessed October 15, 2023).

27

Ioannou O. (2021). The impact assessment of CH interventions: main challenges and GAPs. Econ. della Cult. Spec. Issue2021, 5–13. 10.1446/103680

28