Abstract

What is it exactly about the quest to “green” the performing arts that so fundamentally challenges the sector’s modi operandi? A sense of urgency around climate change and ecological degradation is informing profound changes in the way the arts field sees itself and slowly inducing a discussion on the sustainability of its working practices. However, despite the undeniable planetary emergency, the lumping together of environmental issues and cultural policy and management frameworks remains complex and controversial, especially if considered from the perspective of the European semi-peripheries. By exploring the preliminary results of a nation-wide inquiry among 140 performing arts regularly funded organisations based in Portugal, this paper discusses the implications of the overarching challenge of environmental sustainability for cultural policymaking and arts management, seeking to contribute to a more nuanced and context-sensitive understanding of the “green transition.”

Introduction

In a context where a sense of urgency around climate change, ecological degradation and biodiversity loss is growing each day, every sector of society is affected and challenged to act. In the performing arts, environmental sustainability concerns and related goals – once the purview of innovators only – are now triggering deep reflections (Janssens and Fraioli, 2022: 5) and are increasingly being incorporated in the arts discussion. Ecological distress is affecting artistic and curatorial decisions, as well as challenging production, touring and management models. Undeniably, “greening” the performing arts has become an expanding area of action and attention, with sector’s pioneers such as Creative Carbon Scotland1 or Julie’s Bicycle2 being joined by the most relevant professional players of the field: IETM,3 the European Theatre Convention,4 On the Move,5 among others, have several initiatives under way, materialized by an array of projects and a constant proliferation of reports, toolkits and legislation6 designed to broaden environmental awareness and foster concrete action among arts institutions and practitioners.

Surely, mainstreaming environmental sustainability criteria across the arts and culture funding frameworks can be said to be well under way (Kruger and Feifs, 2023; Vries, 2021). However, while embedding ecological issues into cultural policy may be justifiable vis-à-vis the undeniable planetary emergency, it is not necessarily a consensual case in the performing arts field, and it is especially controversial when considered from the perspective of the European semi-peripheries. In Portugal as in other EU countries, the arts’ “green transition” intersects with the field’s long-standing shortcomings and sparks intense debates on social justice, and greenwashing/artwashing, fuelling the everlasting argument over arts’ instrumentalization.

The ambiguous geographical and cultural position of Portugal (Ribeiro, 2009) - sitting geographically and culturally between Europe and the Atlantic and economically categorized as semi-peripheral – coupled with the country’s tardy democratic turn and the late acknowledgment of its violent colonial action - makes it a remarkable observation point from which to analyse the frictions and contradictions deriving from the overarching challenge of sustainability. Clearly, the questions Portuguese artists and producers are facing are as deeply rooted in national shortcomings as they are global dilemmas; they are utterly practical and indisputably political: should small-scale, not-for-profit artistic and cultural activities based in semi-peripheral countries bear responsibility for the ecological crisis? Should cultural practitioners be held accountable to a problem some of them see as originating and reaching far beyond their power? Should they refrain from intensifying international touring, even in the face of well-known asymmetries inside the EU (Janssens and Fraioli, 2022)? Should ecological and environmental concerns be embedded in cultural policy, and if so, in which ways? Should funding of the arts and culture decidedly change to accommodate sustainability-related objectives?

By exploring the results of a nation-wide qualitative inquiry among performing arts practitioners based in Portugal, we will investigate discourses around the perceived distribution of ecological responsibility in the arts, and the ways in which it intersects with cultural policy as well as with performing arts production and management practices. We will argue that this issue is crucial for the future of arts management, not only since it will likely impact the next generation of producers and cultural managers, “requir[ing] new ways of working” (Theatre Green Book, 2021: 15), but also insofar as it sharply points to the difficulties of parting with arts management expansionist and productivist processes (Rodrigues, 2024).

Methodology

This paper draws mainly upon the examination of a set of data deriving from a nation-wide study (Rodrigues et al., 2024) based on a qualitative survey carried out between January and April 2023 to performing arts organisations in the subsidized sector in Portugal, specifically, organisations receiving support from the Directorate-General for the Arts.7 The methodological choices of that study’s coordinating team reflect a relational and inclusive approach to issues and problems, as well as a determination to conduct research in close proximity to the artistic community. This approach particularly values how the artistic community interprets the proposed themes and frames their contributions, reflections, and dilemmas. This is especially crucial given the complex nature of the research topic and the type of transformations it points towards. In fact, ecological transition has been identified as a transformation that requires “action-oriented co-produced knowledge intertwined with multiple forms of knowledge” and stakeholders (Tengö et al., 2014; Biggs et al., 2021, cited by Biggs et al., 2021).

In this regard, we primarily relied on a qualitative approach, complementing the statistical treatment of the collected data. The qualitative approach, with its flexibility and potential for in-depth inductive analysis, was deemed the most suitable for an exploratory study. Accordingly, procedures for coding the empirical material were employed, guided by Maxwell’s (2005) recommendations on qualitative research design. Categories and sub-categories of analysis were constructed and continuously refined through interpretive exercises, subjected to bivariate analysis, and compared with emerging concepts from relevant literature.

Similarly, since one of the implications of this study is the potential to establish connections with the formulation and adaptation of public policy measures, it was crucial to extensively value the process of listening to cultural agents. This was achieved through the use of numerous open-ended questions and repeated analysis in discussion groups, for instance, in order to steer clear of top-down approaches and the risk of alienating stakeholders (Freeth and Drimie, 2016). This active listening method notwithstanding, we should bear in mind the notion that, by participating in this study, and despite all effective assurances of response anonymization, cultural organisations were likely to be aware that this was a relatively pioneering study in the country, whose findings will be made public and widely disseminated. Hence, it’s reasonable to understand their responses as at least partially stemming from an effort to “construct a positive public-facing” identity (Grove Ditlevsen, 2012).

The abovementioned survey consisted of 49 questions (68 if the sub-questions are considered), of which 18 were optional, 29 open-ended, 33 selection/choice, 2 Likert scale, 1 ranking and 3 of numerical response. Its questions were grouped into three blocks, namely: 1) profile, aimed at collecting data characterising both the organisations and the respondents; 2) discourses and positions, in which respondents were invited to reflect on the interconnection between the field of arts and culture and the issues of environmental sustainability; and 3) practices and actions, about the practical needs and expectations in terms of their own green transition, and that of the public institutions and cultural policies, especially those carried out by DGARTES.

The selected universe – all 594 DGARTES-funded8 organisations – can be credited as relevant since DGARTES is the most important governmental body and cultural policy agent in the Portuguese performing arts context and given that similar institutions exist in many European countries. Considering the type of survey that was to be implemented (considerably demanding since it was long and had several open-ended questions), a minimum overall response rate of 20% was set, corresponding to 120 valid responses. This rate was effectively achieved and exceeded, standing at 24%, corresponding to a sample with a total of 140 valid responses. In addition, to ensure the comprehensiveness, representativeness and relevance of the data collected, minimum distribution criteria were established, which corresponded closely to the characteristics of the pre-defined population.9 These criteria can be considered fully met, as shown in the tables below, which display both the degree of compliance with the minimum criteria and the composition of the final sample.

Theatre and cross-disciplinary arts are the most represented areas - together they make up 62% of the responses (Table 1).

TABLE 1

| Artistic Area | Minimum number of responses | Number of valid responses | Proportion of the total valid responses | Difference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Theatre | 30 | 43 | 31% | +13 |

| Cross-disciplinary arts | 23 | 43 | 31% | +20 |

| Music | 18 | 26 | 12% | +8 |

| Dance | 5 | 17 | 19% | +12 |

| Contemporary Circus and Street Arts | 1 | 4 | 3% | +3 |

| Other(s) | - | 7 | 5% | — |

| Total | 140 | |||

Number of respondents per artistic area.

Source: Own elaboration.

The responding arts organisations were based in more than 60 different cities throughout Portugal, and their headquarters and main activities are mainly concentrated in the Lisbon Metropolitan Area (35%), followed by the North (29%) and the Centre (24%), which, again, is consistent with the distribution at national level in the total universe considered (Tables 2, 3).

TABLE 2

| Main field of activity | Minimum number of responses | Minimum proportion of responses | Number of valid responses | Proportion of the total valid responses | Difference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Artistic creation/production (theatre and dance companies, groups of artists, etc.) | 60 | 50% | 82 | 59% | +22/+19% |

| Artistic programming (festivals, venues, etc.) | 24 | 20% | 53 | 38% | +29/+18% |

Number of respondents per field of activity.

Source: Own elaboration.

TABLE 3

| Region | Minimum proportion of total valid responses | Number of valid responses | Proportion of the total valid responses | Difference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Área Metropolitana de Lisboa | 35% | 48 | 34% | −1% |

| Alentejo | 5% | 7 | 5% | 0% |

| Algarve | 2% | 6 | 4% | +2% |

| Norte | 25% | 38 | 27% | +2% |

| Centro | 15% | 37 | 26% | +11% |

| Região Autónoma da Madeira | 1 resp. | 3 | 2% | +2 resp. |

| Região Autónoma dos Açores | 1 resp. | 1 | 1% | 0 resp. |

| Total | 140 | |||

Number of respondents per region.

Source: Own elaboration.

In terms of type of funding, the study aimed for at least 50% of organisations which were recipients of Sustained Support (Table 4). The Sustained Support Programme is divided in two funding modalities, a 2-year and a 4-year cycle, with the possibility of automatic renewal10 for the same period. It is, therefore, the most stable form of public funding in the Portuguese performing arts scene, which is relevant considering the overall precariousness of the sector. The rationale behind aiming to have at least half of the answers coming from this type of organisations is manifold ranging from issues of scale/resources to ethical considerations. Firstly, we bore in mind the typical fragmentation of the sector, which is reflected in the survey statistics: the majority (80%) of respondents correspond to micro-organisations, employing less than 10 people. This reinforced our determination to at least target organisations which had Sustained Support, assuming that they would be better equipped to deal with sustainability issues, given their relatively more stable funding framework. Also, we had ethical concerns: we wished to avoid overburdening smaller groups or solo artists and cultural professionals, which tend to work alone, have less resources and smaller or non-existent teams to help with a long survey. Finally, we thought that relying heavily on regularly funded organisations would better serve comparative research in the future, and facilitate benchmarking, seeing that one of the funding agencies largely held as a pioneer in this field, Arts Council England, had launched its Environmental Policy Programme exactly by involving the National Portfolio Organisations and major Museum partners (Taxopoulou, 2023: 19).

TABLE 4

| Type of Funding/Grant Scheme | Minimum number of responses | Minimum proportion of responses | Number of valid responses | Proportion of the total valid responses | Difference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sustained Support (Apoio Sustentado) | 60 | 50% | 82 | 59% | +22/+19% |

| Project-based Support (Apoio a Projetos) | Not defined | 61 | 44% | N/A | |

| Other | Not defined | 34 | 24% | N/A | |

Number of respondents per type of funding.

Source: Own elaboration.

Overall, the sample considered in this study is, therefore, consistent with the universe of DGARTES-funded organisations in terms of distribution by artistic discipline, region, type of funding, and it represents a balanced split between venue-based arts organisations and project-based or independent collectives. The universe of respondents is also gender-balanced, with a slight preponderance of respondents who identify as women (51%). In terms of education/qualifications, the sample mirrors the high qualifications of the sector, with 90% of respondents having a graduate degree and 61% postgraduate level education. Given the centrality of DGARTES-funded organisations in the performing arts ecosystem, and the comprehensiveness of our sample, it can be said that this dataset carries public policy interest (Caust, 2017), and that it invites comparisons to be made across EU countries, as well as longitudinal research.

This sample was complemented with a range of five in-depth interviews to the same profile of respondents (artists, producers, and arts managers).11 Both have been object of content analysis based on different codification procedures which we will detail throughout the discussion, for a more integrated approach.

Discussion

Environmental sustainability: attitudes, problems, and perplexities

One of the fundamental tasks of this exploratory survey was to unpack the interpretation of “sustainability” among arts practitioners. Given the breadth, ambiguity and polysemy of the concept of sustainability, we decided to classify the (open-ended) responses into three categories, seeking greater clarity about the respondents’ representations of this topic. We, therefore, divided the responses into sustainability as environmental sustainability, which included answers relating to moderation and balance in consumption, and emphasised the necessary relationship between humanity and the planet; sustainability as social sustainability, where the dimension of living conditions is evident and sustainability is unequivocally linked to the idea of a dignified life in terms of human and social rights; and finally, sustainability as sustainable development, which includes allusions to the need to change the political and socio-economic models that determine our development matrix. The depth and range of interpretations proposed by the respondents reveal a clear understanding not only of the latitude of the idea of sustainability itself but also a conviction that it is unequivocally associated with living conditions, quality of life and social rights. A significant number of respondents also see the concept of sustainability as an ideal towards which aspirations for a social and economic paradigm shift converge. It is clear that there is a significant tendency not to subsume sustainability under environmental sustainability, recognising the profound interdependencies with other “sustainabilities” and how these interdependencies (when put into perspective) raise concerns.

We also wanted to understand how they made sense of the notion of sustainability if directly related to the arts. In order to do that, we analysed their answers to different questions through Kate Power’s triptych. Power (2021) describes three main connections: a) sustainability through the arts – where they highlight the narrative and communicative capacity of the arts and their potential to raise awareness and change behaviour; b) sustainability in the arts – where respondents give prominence to the need to know and reduce the environmental footprint of the arts and to incorporate environmental sustainability into cultural practices and policies; and c) sustainability of the arts - emphasising organisational sustainability, the sustainability of artistic careers, the sustainability of the artistic project in temporal and financial terms, the sustainability of the sector itself. Overall, in terms of the number of responses, we observed a certain predominance of arguments favouring sustainability in the arts over the other two categories, through the arts and of the arts, which would indicate that respondents attach greater importance to strictly environmental sustainability, and to how the arts can meet and reduce their own “ecological footprint.”

Another major objective of our survey was to find out about cultural professionals’ opinions and discourses around the perceived distribution of specifically ecological and environmental responsibility in the arts, and, concretely, the ways and the extent to which they deemed that sustainability should or shouldn’t be embedded into cultural policy and into the production and management of arts. As stated before, we were making use of the ambiguous position of Portugal to look at the frictions and contradictions deriving from the overarching challenge of sustainability. Some of those contradictions became noticeably evident in the first set of results that our study analysed, as we shall see. A part of the questions was designed to help us understand the viewpoints of cultural professionals regarding the intersection between the field of arts and ecological and environmental issues in general. We wanted to grasp whether the relevance of this relationship was evident, given the characteristics attributed to the ecological problem: its massive scale and extent in space and time, and above all, its “viscosity” (Morton, 2013), i.e., its capacity to “stick” to all objects and decisions we make and its ability to appear so monumental and close that they are almost perceived as unrealistic. Judging by the first outcomes of our inquiry, the magnitude and urgency of ecological issues is apparent to culture professionals, who do not hesitate to connect their field of work with this overwhelming challenge.

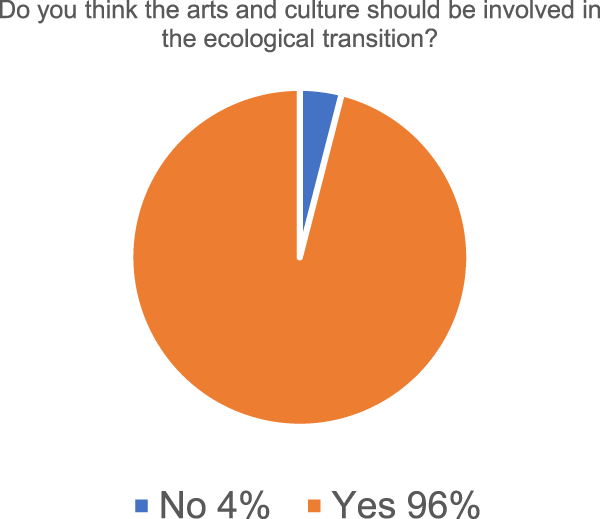

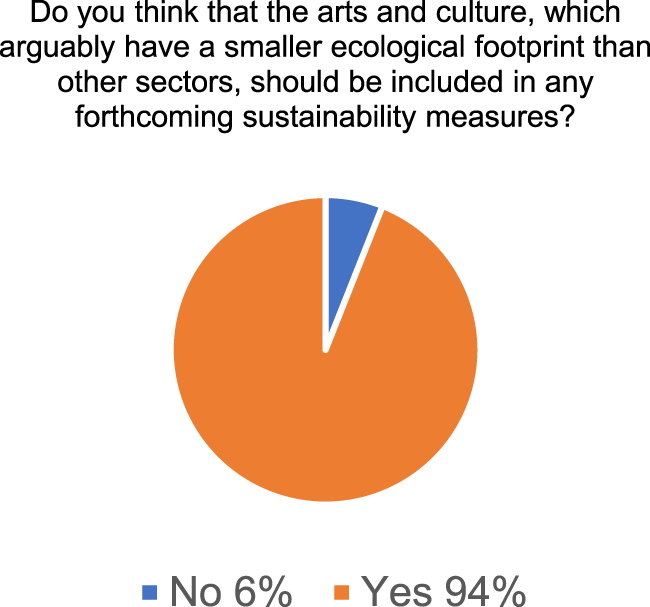

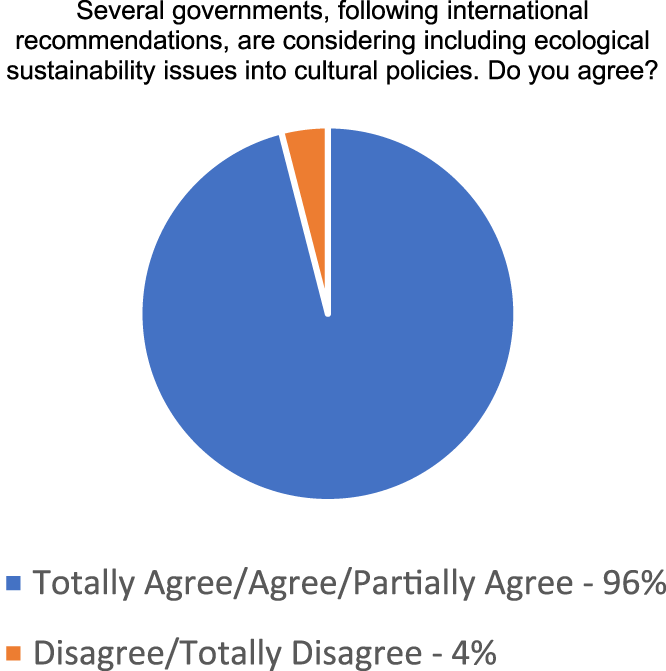

An impressive 96% believe that the arts and culture should be involved in the ecological transition (Graph 1), a result that is almost the same when we slightly change the question to include the issue of “scale” (Graph 2).

GRAPH 1

Positioning regarding the intersection between arts and environment. Source: Own elaboration.

GRAPH 2

Positioning regarding the intersection between arts and environment. Source: Own elaboration.

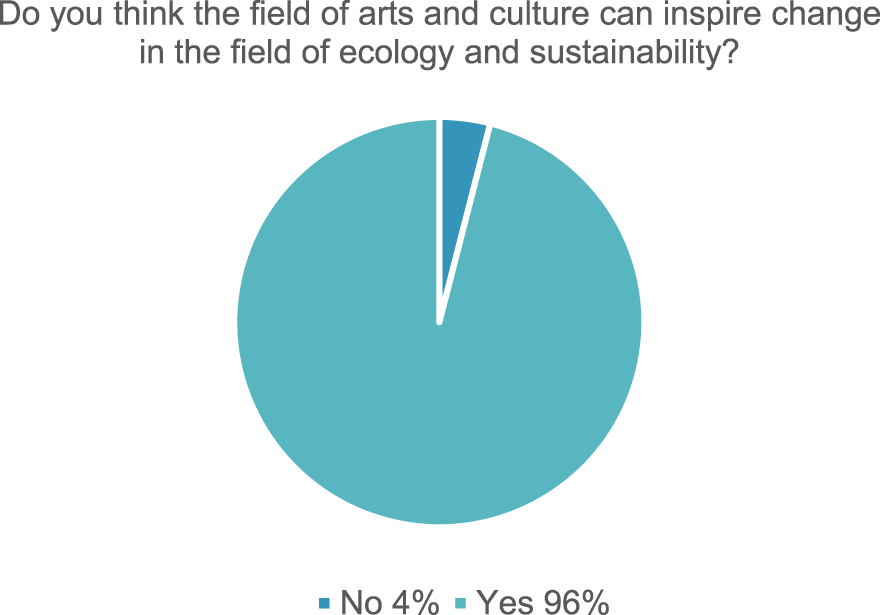

These results speak volumes in terms of how they see the junction between arts and sustainability and reveal an enormous confidence in the power of arts in this realm (Graph 3).

GRAPH 3

Role of art in inspiring change towards sustainability. Source: Own elaboration.

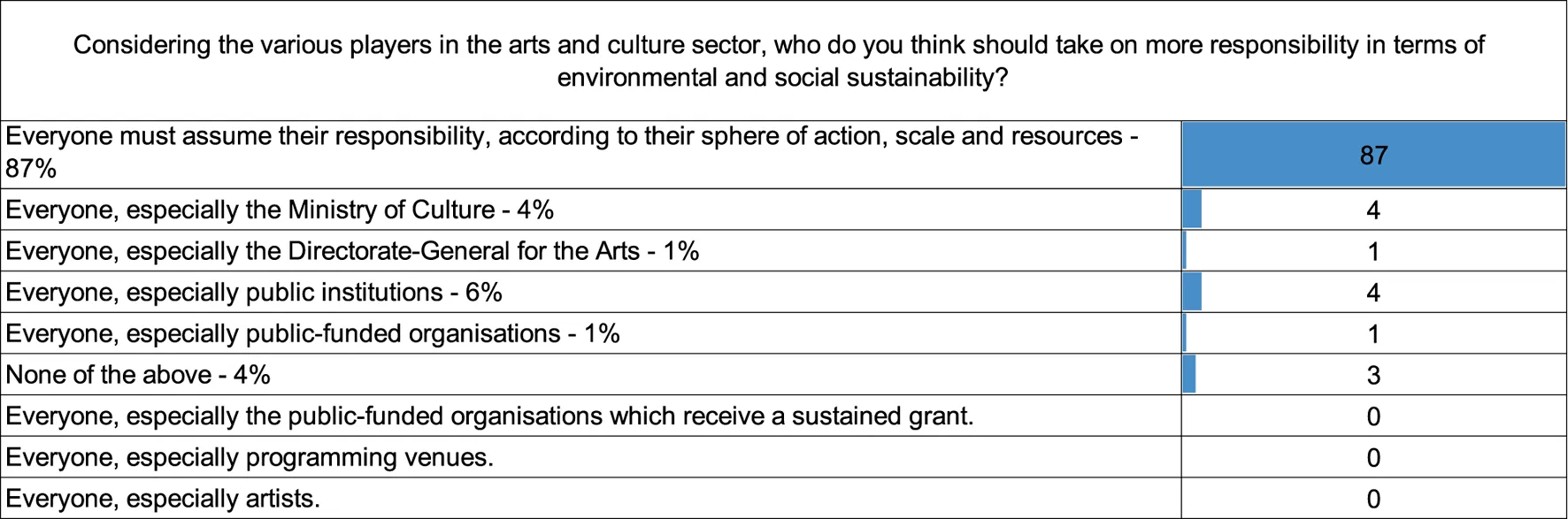

Since power and responsibility are usually interrelated, it is understandable that a majority of respondents (87%) agree that responsibility for environmental and social sustainability should be taken on by all actors according to their sphere of action, scale and resources (Table 5).

TABLE 5

|

Distribution of responsibility regarding sustainability.

Source: Own elaboration.

It may seem striking that the respondents did not take the opportunity to hold DGARTES or the Ministry of Culture more directly accountable, thereby separating out responsibility at the individual (micro), organisational-institutional (meso) and governmental-systemic (macro) levels. However, in hindsight, we could perhaps have phrased the question differently. All the answer options in this question began with “everyone,” which may have contradicted the goal to find out who the respondents thought should take on more responsibility. The rationale behind that phrasing was the intention to acknowledge that, given the magnitude of the ecological transition, no-one individually can bear all responsibility. Instead, the question wished to point towards sectoral leadership, but apparently failed at that. Also, the second part of the first sentence, where a principle of “common sense” is introduced - stating that responsibility should be according to each actor’s “sphere of action, scale and resources” - could have been left out. These reflections can guide further research into the same or distinct artistic communities, and they are relevant here not only as a way of acknowledging the possibility of failure in the process of research - and thereby advocating a feminist, radically transparent research code of practice (Boncori, 2023) - but especially because they may reveal the extent to which this idea of “collective responsibility” is being propelled.

It is therefore important to read these results not only as symptoms of how “evident” and “urgent” the need for ecological transition is perceived to be, but also in the light of the Marxist critique of the climate change debate, which points out that this understanding of evidence/urgency is perhaps a bit too consistent with the identitarian mobilisation that is typical of cultural workers, and with the views of the professional class they are usually associated with, in sociological terms. A case in point of this critique is Mathew Huber, who poses that by failing to decisively connect climate change with capitalist production (i.e., industrial production) and classifying “environmental politics as a ‘new’ and non-class-centred social movement,” we have wrongly been led to believe that we are primarily responsible for climate change, and have become anxious about our “carbon guilt” (Huber, 2022: 21): “[w]hen confronted with the question of responsibility – the question of who cooked the planet – the climate movement is highly confused. Usually the answer points to “all of us.” The story of climate responsibility we hear is one of millions of diffuse individual choices – adding up to a planetary impact” (Huber, 2022: 10). For Huber, this would explain the “popularity” of strategies based on the reduction of our carbon footprint and related compensation mechanisms, while failing to uncover the more important question, “who do we believe has the real power over society’s economic resources?” (ibidem: 10). Indeed, our survey showed a clear tendency towards the rationale that involving the arts and culture in environmental efforts makes sense insofar as it is a sector as any other - ecological concerns cutting across all societal activities. This is despite the fact that the wording of more than one question in the survey mentioned the relative scale/dimension of the arts and culture sector’s ecological footprint, among other aspects that could be used to contextualise the answers. In fact, the respondents place a significant importance in the sector’s own alleged impact as a reason for its involvement in the ecological transition, as we can see in Tables 6, 7 below.

TABLE 6

| Linking arts and culture with environmental issues makes sense because | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arguments | Relative strength of the argument (frequency with which respondents mention it) | Correspondence - responses | ||||||||||||

| 1 | ...it is a problem of individual responsibility/it speaks to a moral dimension. | 18 | 1 | 23 | 25 | 28 | 29 | 34 | 41 | 48 | 61 | 62 | 65 | 84 |

| 113 | 118 | 123 | 130 | 131 | 138 | |||||||||

| 2 | ...arts can/should contribute to changing mentalities/raising awareness in other sectors/among audiences. | 22 | 13 | 19 | 27 | 35 | 36 | 38 | 42 | 43 | 60 | 67 | 69 | 71 |

| 79 | 81 | 101 | 108 | 116 | 122 | 124 | 129 | 139 | 140 | |||||

| 3 | ...the sector has an environmental impact and must work to reduce it. | 26 | 4 | 7 | 8 | 11 | 16 | 22 | 28 | 33 | 38 | 39 | 44 | 45 |

| 53 | 57 | 64 | 66 | 67 | 70 | 73 | 101 | 104 | 107 | 112 | 114 | |||

| 120 | 139 | |||||||||||||

| 4 | ...it is a problem/concern that cuts across all social activities. | 36 | 5 | 13 | 18 | 19 | 24 | 29 | 30 | 31 | 46 | 47 | 48 | 55 |

| 58 | 68 | 76 | 79 | 80 | 82 | 84 | 87 | 95 | 96 | 103 | 105 | |||

| 108 | 109 | 110 | 117 | 123 | 125 | 126 | 127 | 133 | 135 | 136 | 140 | |||

Arguments to embed environmental issues in the arts and culture.

Source: Own elaboration.

TABLE 7

| Arguments | Examples/Responses- statements | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | ...it is a problem of individual responsibility/it speaks to a moral dimension | R113: “It’s a question of morality. We should all contribute, even if [our carbon footprint ] is not very relevant.” |

| 2 | ...arts can/should contribute to changing mentalities/raising awareness in other sectors/among audiences | R43: “Our area shapes behaviours and must lead this transformation.” |

| 3 | ...the sector has an environmental impact and must work to reduce it | R107: “I don’t think it’s an activity that has a small ecological footprint. Just think of the heating of the venues, the energy impact of all the equipment in a theatre, the amount of paper wasted on marketing, the water bottles, among other factors. The impact is much greater than one might think.” |

| 4 | ...it is a problem/concern that cuts across all social activities | R71: “All sectors must be equally concerned, since the struggle is the same.” |

Arguments to embed environmental issues in the arts and culture.

Source: Own elaboration.

To better understand the reasons invoked by the respondents, we asked them to justify their answers, using an open-ended field12 where they could freely expand on their positions. Based on 111 valid statements, we did a first reading to familiarize ourselves with the range of arguments used, followed by a second reading seeking to identify the stronger, most recurrent lines of thinking. A second team-member repeated the exercise so that a team debate could be held to cross-verify our choices. After the four main arguments were identified and agreed upon, we proceeded to establish correspondences, registering their relative strength by quantifying the number of times they were mentioned. Tables 6, 7 (above) show the relative strength of the ideas that (3) the arts own environmental impact is not negligible, and efforts should be made to reduce them; and (4) the idea that there is no fundamental difference between the arts and culture sector and any other social activity, the environment cutting-across all spheres of human activity.

The reasoning behind the respondents’ statements may be interpreted as a sign that the performing arts are “irrevocably entering a process of ecological transition,” as Taxopoulou argues (2023:2), hence ready to admit that the gravity and the sheer dimension of the ecological situation are enough for the cultural sector to “declare emergency”13 and to be “determinate in taking centre stage in the sustainable transition” (Taxopoulou, 2023: 1) since, as Taxopoulou points out, a significant momentum seems to have been reached in many different geographies. Nevertheless, our interpretation points to additional perspectives, which do not undermine Taxopoulou’s claim, rather complexify it with a supplementary set of questionings.

A first hypothesis could point towards some degree of environmental illiteracy,14 and Portugal’s cultural sector fairly weak involvement in the debate around climate justice. This would mean that, prior to this survey, the respondents may have had few opportunities to engage in situations where they could discuss and learn about the implications of considering ecological and environmental issues in their sector, and thus become acquainted with the existent critique, or at least to become familiar with counter-arguments that relativise the importance of involving this sector, either by downplaying its carbon impact, or by putting the sector’s impact and efforts in a wider political and economic context, as suggested by Demos (2016), when he wonders whether artistic practices can challenge the neoliberal governance.

A second conjecture (which holds connections to the prior) could attest to the fact that a more ecosystemic, context-specific discussion of the sector’s involvement in the green transition is rather absent in the myriad debates and publications, with most of them elaborating on practical ways to engage in decarbonization strategies, adaptation and mitigation processes, urging cultural agents to develop awareness-raising activities, etc. – without first addressing “the elephant in the room”: why, indeed, should a sector as fragile (in multiple dimensions) as the arts and culture, in contexts where working in the arts is already very often a quest for survival, engage in this colossal challenge? And how can cultural professionals make sense of their stance in the face of other, more powerful social and economic sectors? How can the ethos of cultural organisations be “greened” without confronting the socio-economic background provided by neoliberal capitalism? Obviously, discussing the implications of considering profit-driven economic systems (Huber, 2022; Klein, 2015) and fossil capital (Malm, 2016) as the major variables in tackling climate change (and the associated classification of the ecological transition as fundamentally a “class struggle”) lie outside the scope of this paper, but it is useful to keep them in mind for sake of some of the discussions that we will be presenting later in this text, regarding dissent, ethics, and a critical juncture for arts management.

At this point, a note should be made about how extremely complex researching this issue proves to be. How can we inquire about such an “obvious urgency” without bordering on or legitimizing science and climate change dangerous denialist discourses? How can we make space for doubt, while Rome is burning? My position as a researcher is unequivocally committed to the goal of a more sustainable world, and this necessarily includes the arts and culture sector. However, my commitment involves problematizing issues, even when they further complicate an already challenging path. To close on this point, I will add that my commitment to radical transparency, as mentioned before, also implies a way of conducting research, and writing about it, that does not shy away of shedding light upon these contradictions and difficulties, which I argue are less part of the public discourses as they perhaps should be.

Between the urge to be sustainable, and the fear of heightened inequalities

As we have seen, results from our survey are in line with the ideas that are consistently becoming part of both official and independent guidelines and reports on the subject. Those can be described as, on the one hand, the notion that the environmental concerns are inescapable and are already an objective element of consideration in the sector - “most of our professional work and operations are already weighed against the principles of sustainability” (Lalvani, 2023: 8); and, on the other, the belief that those principles should guide our actions – “sustainability is the most urgent matter in today’s world and should therefore be at the core of our missions, projects and objectives” (ibidem). But is there a difference between acknowledging this in general, and making a concrete connection to cultural policy-making?

In our survey, when asked whether they agreed with the fact that several governments were “considering including sustainability issues more expressively in cultural policies,” an expressive majority (96%) responded positively (Graph 4).

GRAPH 4

Sustainability and cultural policies. Source: Own elaboration.

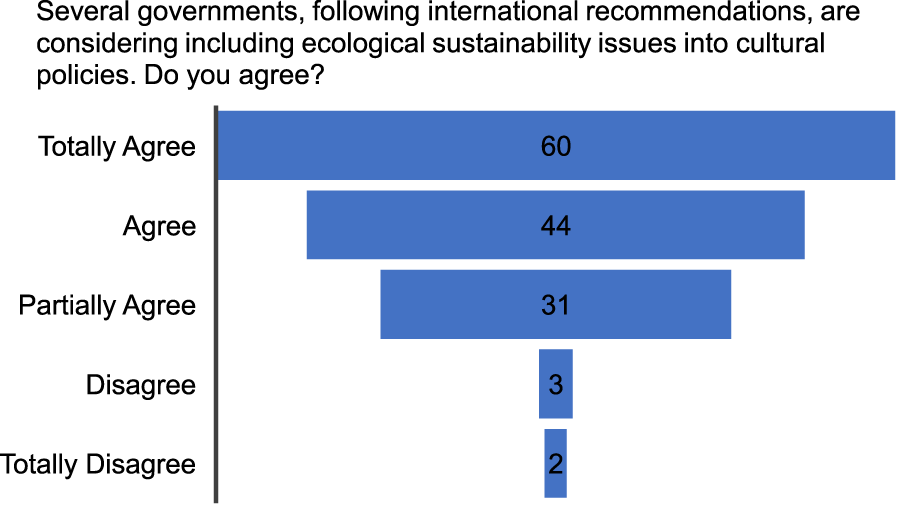

The degree of agreement, however, varies (Graph 5), somehow already indicating that this apparent unequivocal consensus hides some nuances that deserve to be analysed more rigorously, and which seem to escape the official discourse of the sector’s publications on the matter.

GRAPH 5

Sustainability and cultural policies. Source: Own elaboration.

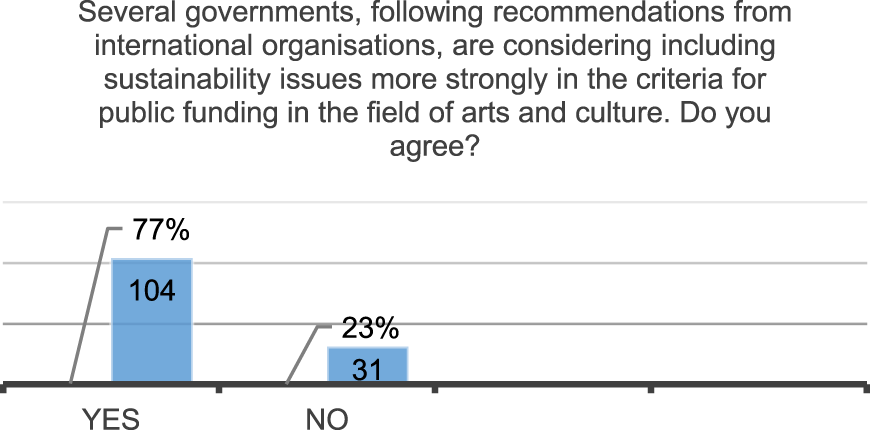

The pattern was roughly repeated when the question more explicitly mentioned the possibility of sustainability issues being incorporated “in the criteria for public funding in the arts and culture field” – 77% expressed their agreement. But although the overall pattern of response remained the same, the degree of agreement, one must notice, decreases significantly, almost 20% (Graph 6).

GRAPH 6

Sustainability and culture funding. Source: Own elaboration.

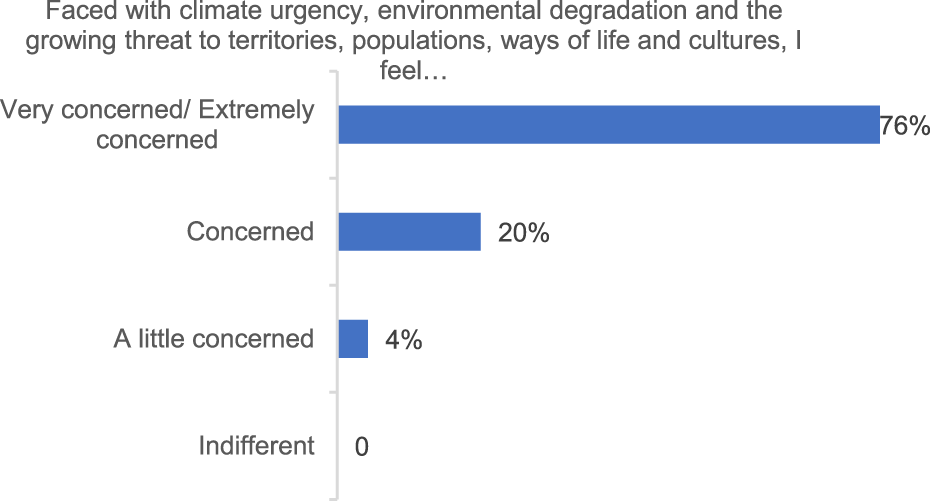

These nuances notwithstanding, the majority of the respondents, the survey showed, seem to welcome a greater incorporation of environmental sustainability issues in cultural policies. These attitudes are consistent with the respondents’ level of preoccupation with climate urgency (Graph 7) – again, a significant majority 76% reported being “very” or “extremely” distressed; 96% either concerned or very/extremely concerned.

GRAPH 7

Respondents’ level of concern about environmental issues. Source: Own elaboration.

Given the high topicality of the issue at stake, one should definitely consider the effect of some degree of social desirability bias (Krumpal, 2013) as well as the wish to present a positive public-facing identity (Grove Ditlevsen, 2012) throughout the survey. Afterall, as Rodriguez put it in his now famous open letter to Jerôme Bel, who would want “to be that Donald Trump who stands against Greta Thunberg?” (Rodríguez, 2021). His metaphor strongly indicates how powerful the tendency for one to publicly acknowledge the gravity of the current ecological situation is – the term “planetary emergency” having entered mainstream public discourse. A closer examination, however, reveals the issue to be far more controversial than the quantitative results that we have analysed so far might suggest. If it weren’t so, how then to account for the various conflicts that arise from a closer examination of the survey’s results – and, specifically, from the content analysis of the written responses, in which the cultural practitioners involved in this study were invited to further explain their thoughts and attitudes towards the intersection between their field of work and the larger ecological imperative?

Indeed, when confronted with the potential transformations that “the green transition” can bring into the sector’s working practices, many reveal fears of (a) instrumentalization and/or threats to artistic freedom and (b) tokenism. At the same time, the respondents consistently raise issues that are heavily context-related, and which are arguably relevant for other semi-peripheral countries, namely issues related to (c) increased financial restraints and/or increased difficulties in accessing funding, (d) instability/fragility of cultural policy frameworks, (e) infrastructural inequalities and (f) fairness and historical (in)justice. Lastly, another set of responses conveys their suspicion of (g) the efficiency of sector-based and nation-based approaches as well as distrust in “one-size-fits-all” solutions, to a problem they characterize as a product of “global inequalities” requiring a break off with current social and economic models. These seven points were identified through the content analysis based on a prior codification exercise activated by a set of words related to conflict, stress or dissent. The analysis followed the process described before, by which key ideas are double-verified in a two-step codification exercise. The following Tables 8, 9 summarise a representative illustration of the type of statements that were found to be corresponding to different arguments, as well as their relative strength.

TABLE 8

| Linking arts and culture with environmental issues makes sense but/if | ||

|---|---|---|

| Arguments | Relative strength of the argument (frequency with which respondents mention it) | |

| A | Instrumentalization and/or threats to artistic freedom | 9 |

| B | Tokenism | 3 |

| C | Financial restraints and/or difficulties in accessing funding | 11 |

| D | Instability/fragility of cultural policy frameworks | 29 |

| E | Infrastructural inequalities | 5 |

| F | Fairness and historical (in)justice | 7 |

| G | Distrust in adequacy of sector-based, nation-based and “one-size-fits-all” approaches | 14 |

Illustration of main points raised by the respondents.

Source: Own elaboration.

TABLE 9

| Arguments | Examples/Responses- Statements | |

|---|---|---|

| A | Instrumentalization and threats to artistic freedom | R100: “I do not think it is legitimate in democratic systems to use public funding to instrumentalize cultural production” |

| R23: “I fear a lot about what consequences this could have for us artists. I feel it could harm us professionally and put us in even more precarious situations and with less artistic freedom…” | ||

| B | Tokenism | R135: “It all seems to me like trendy agendas that are going to be made to win funding/grants” |

| R101: “this is an appropriation of the term ‘culture’ to increase spending on ‘decorative’ and superficial matters” | ||

| C | Financial restraints and difficulties in accessing funding | R111: “there will have to be a transition period and extra financial support for cultural operators to be able to make changes” |

| R2: “could constitute a further barrier to accessing public funding in certain situations” | ||

| D | Instability/fragility of cultural policy frameworks | R14: “If funding in Portugal continues to operate at such a low level, one might almost consider it ridiculous that choices can be made at this stage based on environmental sustainability criteria. Only with a stabilised cultural landscape and some financial stability should funding bodies start to be required to meet such criteria” |

| R56: “The financial model of the cultural sector is generally so fragile, that introducing sustainability related criteria would be desastrous to some structures” | ||

| E | Infrastructural inequalities | R109: “It is not fair to encourage people to change from air to rail (especially in Portugal where rail links with the rest of Europe are practically non-existent)” |

| R99: “I agree if the process is accompanied by an extraordinary effort to develop sustainable public mobility infrastructures throughout the country and at its intersection with international territory” | ||

| F | Fairness and historical (in)justice | IT2: “it is up to us to think about the quality of life of artists who live on the margins. Artists who do not have the privilege of receiving support, nor of accessing mobility. I believe that in order to move towards the issue of environmental sustainability, it is necessary to think about reparations and confronting racial, social and cultural inequalities, as well as facing the problem of institutional and structural racism” |

| G | Distrust in adequacy of sector-based, nation-based and ‘one-size-fits-all’ approaches | R99: “as long as we are similarly applying similar rules to public funding to other sectors of activity, namely tourism” |

| R37: “The question is always the mould in which these policies are implemented. If they are mere copies of international models or if they contemplate the reality of the country” | ||

Illustration of main points raised by the respondents.

Source: Own elaboration.

To try and make better sense of these points, we subsequently grouped them into three major categories, each pertaining to a different dimension/level of conflict: political/systemic/ethical; policy/government/national; and practical/resource/material. A simple visualization of how the points relate to the three categories (Table 10, below) exposes the significantly political aspect of the juncture between the arts and the ecological urgency.

TABLE 10

| Arguments | Type of conflict/friction | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Political | Policy | Pratical | ||

| A | Instrumentalization and threats to artistic freedom | ● | ||

| B | Tokenism | ● | ||

| C | Financial restraints and difficulties in accessing funding | ● | ● | |

| D | Instability/fragility of cultural policy frameworks | ● | ● | |

| E | Infrastructural inequalities | ● | ||

| F | Fairness and historical (in)justice | ● | ||

| G | Distrust in adequacy of sector-based, nation-based and 'one-size-fits-all' approaches | ● | ● | |

Types of conflict.

Source: Own elaboration.

Indeed, most of the respondents’ perceived conflicts seem to be of a political/ethical nature, poignantly indicating the contextual situatedness of such a clearly global problem. The practical obstacles notwithstanding,15 Portuguese arts practitioners appear in this study to be acutely aware of the overarching political implications of “green transition” measures at sectoral level, and vigilant of the contradictions that such transformations entail when associated with Portugal’s specific geographical and historical circumstances.

Until 1974, Portugal was a country blocked-in on itself - a fascist and colonialist dictatorship, that described itself as “proudly alone.” I am a dancer and choreographer of a generation that emerged when the country opened up to culture and arts from other countries and latitudes. I am the result of the direct exchange that was offered to me while being part of the audience, with artists and proposals that opened up my horizons, not only artistic but also social and cultural. (…) The circulation of art and artists in the European space is therefore (…) a question with a deeper and wider social and cultural scope. (…) Will carbon savings in the circulation of arts be worth the cost of a Europe more vulnerable to extremist nationalisms? We have to look at the bigger picture that this whole issue implies. [IT3]

The fact that we are based in Portugal poses us quite a number of challenges, as a theatre company. The fact that our country is a very peripheral one, at the edge of the European continent … The fact that the country’s railway network is very small and very old, and that has not been renewed for at least 100 years, also makes it very difficult, in national terms, to avoid choosing the car to go on tour, for example, and to not use the airplane when it comes to international travel, because the Portuguese railway network is not combined with the European railway networks.16 [IT1]

Conclusion

In lieu of a conclusion: the complex contextual situatedness of the green transition

Although we have underlined the more political and ethical dimensions of the conflicts and fears voiced by cultural professionals throughout our inquiry, the fact remains that there is a richness of potential conflicts/fears arising in all three different levels: political, policy, and practical. This could be a powerful indication that - despite the massive discursive adherence to the sense of urgency around tackling climate change and environmental degradation - arts practitioners are very much aware that doing that presents specific challenges vis-à-vis their social and professional context. Their statements potently illustrate the range of complexities and perplexities motivated by the green transition, as well as the need to be cautious with “one-size-fits-all” solutions which are typically propelled by rapidly expanding international political agendas. In addition, they clearly articulate the indisputable need to promote significant transformations towards a more eco-responsible arts sector with the challenge of overcoming various structural weaknesses that to this day still mark the possibilities for development of the arts field in some European countries, while also incorporating concerns with social justice and historic reparation of global inequalities. Critically, they help us understand the essential need to approach the entanglement of the arts and sustainability in a way that does not avoid the inherent complexity, nor the dissent that the issue entails, even if that might mean working through challenges and contradictions of gigantic proportions.

The analysis we were able to do within the scope of this paper is limited to an overall assessment of major frictions and contradictions that arise when arts practitioners are confronted with the ecological imperative. The way they are conveyed does not at all, we expect, frame them as being an absolute obstacle to the adoption of environmental-friendly actions. In fact, as we have also seen, the best part of our respondents was adamant about the need to progress towards a greener sector. Instead, these results are relevant as a powerful cautionary tale, in at least two ways.

One the one hand, the perspectives and experiences of Portugal-based art practitioners remind us that a proliferation of how-to handbooks, practical guidelines and toolkits, institutional reports and legislation might not be enough to foster concrete actions if certain structural (social and economic) difficulties and inequalities are not overcome – and that there is a need for the sector to further explore context-appropriate, social justice-oriented decarbonisation strategies. This entails remaining sceptical of globalising directives aimed at horizontal public policy-making, which can hardly produce the same results in different contexts. Hard facts such as different traditions of arts funding, and funding levels, stability of cultural policy frameworks, access to information, infrastructure, acquisitive power, etc., need to be better reflected in policies and publications. But soft facts play a role, too, and they become apparent in the struggle to either translate, adopt or reject fast-spreading keywords related to the “green” transition. In fact, in the Portuguese language, for example, there is no easy equivalent to the use of the word “green” in a sentence such as “greening the theatre.” But this is not (only) a grammatical or translation problem, but again one of context-sensitive embodiment. Anecdotal evidence of this is rich. An administrator of a top cultural institution recently approached me at a public gathering, quietly whispering about a just-discovered urgent internal need: in order to engage the staff, they needed to find the corresponding vocabulary in Portuguese that could help everybody make sense of the institution’s ecological efforts. As another culture professional put it, “As cultural agents, we need to analyse and reflect on (…) the discretionary application of sustainability models taken from toolboxes with clean, green graphics written in English. (…) The widespread use of English terms in the field of sustainability shows the assimilation of discourses colonised by a global English from emancipated minds that we reproduce without question.17” Le parole sono importanti!, words matter, as Nanni Moretti18 reminds us.

Another way in which the partial results we have discussed here may be relevant is the fact that the underlying political nature of the majority of the concerns they raise is a strong reminder that the ecological imperative will never be fully addressed through engaged isolated interventions. This is a strong endorsement of Taxopoulou’s claim for robust “climate governance” mechanisms, since her research clearly showed that “[t]here are certainly limits to what the sector can achieve through self-regulation. The transition requires wider, systemic change, all-encompassing regulatory and support frameworks and an unprecedented recalibration of public and private investment” (Taxopoulou, 2023: 37). This reference to “wider, systemic change” can be taken broadly, with regard to changes in terms of the current socio-economic model, but it obviously also encompasses the need for major changes in the very way the cultural sector has become accustomed to operating and, as such, calls for transformation in the field of cultural policy and, importantly, in arts management itself. In fact, although the need to respond to the demand of ecological sustainability has been dubbed as the green transition, the changes it brings about are less a transition from one behaviour to another than a deeper transformation – one that points towards system change, especially given that the arts and culture sector has been operating on “survivalist mode” (Elfving, 2020), strongly conditioned by the growth-oriented capitalist paradigm (Dragisevic Sesic, 2021) and over reliant on expansionist and productivist processes (Rodrigues and Ventura, 2024).

Implications for arts management

A final short reflection that this paper wants to suggest is precisely about the degree of transformation that the decarbonisation and green/just transition strategies entail for the field of arts management. As many recently published reports maintain, the cultural sector will have to fundamentally be ready to reposition itself in this new reality, dismissing any attempts at “normality” and interrogating the sector’s modes of production and operation (The Shift Project, 2021). Likewise, the scope of transformation required in the arts and culture realm may (and perhaps should) lead to a fundamental transfiguration of cultural policies. Arts management will thus be required to contribute to innovation in cultural policy-making to future-proof them in a climate-changed, carbon-negative world. Whether that means simply adapting/updating current policies or introducing emergent/disruptive concepts and measures into cultural policy (Torrens, 2021) remains to be seen.

Just so, part of our research (Rodrigues, 2024) has been focusing on various elements that have pushed the field of cultural management to review its assumptions and modi operandi, arguing that the field is at a critical juncture that we must fully acknowledge and seize.

This critical juncture of arts management is characterised by a shift in the focus of arts managers’ concerns. Since they are finally freed from explaining what is it that they do (the historical process of emergence and social legitimation of the profession being almost complete), they can now dedicate themselves to discussing how they work. Put differently, they can engage in finding and debating the ethical and critical foundations of their daily doings and confront some of arts management’s underlying premises and basic processes. Case in point, arts managers have been highly active in facilitating international networking, presentation and constant travel in an unsanctioned system of high mobility, hopping on and off of conferences, festivals, and many other kinds of professional gatherings.

The idea of mobility (…) has become the defining element of success. It doesn’t even matter what you’ve done concretely, you just list I don’t know how many residencies in three countries, and put together a European network - it’s getting to this level of abstraction. Your job is more and more about interconnecting, and less about what you actually do.19

Arts managers, being responsible for the distribution of works of art and artists, have been determining agents of internationalisation practices, actively participating in the plethora of festivals and platforms that offer visibility and “leverage” to a series of “rising stars,” following one another at a dizzying, consumerist pace. Arts managers have also been consistently working towards expanding their audience numbers, their reach, their budget, their sponsorship, and sometimes even their buildings.

The proximity of this professional field to this constant quest for power and continuous growth is now fundamentally challenged by the discussions around “scaling down” or “slowing down” as some of the strategies towards a greener future. Importantly, if one is to seriously consider the political and ethical concerns expressed by cultural practitioners in our survey, they suggest that arts managers should work on a critical examination of its own professional underpinnings, on the values and specific language it has developed and spread, and not only come up with practical or prescriptive solutions for decarbonising their operations. I posit that this is fundamentally a good thing. It allows us to look at this critical juncture as a turning point, rejecting the expansionist and productivist ethos that was for such a long time at the core of arts management, and push it towards a conceptual and practical reassessment of its assumptions and workings. It might just be that the ecological imperative invites arts managers to the table, engaging in the most important conversation of the years ahead.

Statements

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Author contributions

VR: Literature review; data analysis; writing.

Funding

The author declare that financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This research has been funded by national funds through FCT – Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia, I.P./MCTES, in the scope of the project GREENARTS. Green Production – Performing Arts in Transition under the Grant 2022.01609.PTDC.

Acknowledgments

This article has developed from an initial presentation at the ENCATC - the European Network on cultural management and policy - Congress held in Helsinki in 2023. On that occasion, it received the Best Research Paper Award. The ENCATC Best Research Paper is awarded, on the occasion of the ENCATC Annual Congress, to the best work among those submitted for the ENCATC Education and Research Session. This recognition, awarded by an international Jury composed by members of the Congress Scientific Committee, includes the publication of the paper in the European Journal of Cultural Management and Policy in full open access, thus making the research available and visible for the research community in the field.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Footnotes

1.^ https://www.creativecarbonscotland.com/

2.^ https://juliesbicycle.com/

4.^ https://www.europeantheatre.eu/

6.^To mention just a few relevant reports and initiatives: Julie’s Bicyle: Culture: The Missing Link to Climate Action (2021); Voices of Culture, Culture and Sustainable Development Goals: Challenges and Opportunities – Brainstorming report (2021); United Cities and Local Governments (UCLG), Culture in the Sustainable Development Goals: A Guide For Local Action (2018); The Shift Project, Décarbonons la Culture (2021); European Commission, Directorate-General for Education, Youth, Sport and Culture, Stormy times – Nature and humans – Cultural courage for change – 11 messages for and from Europe (2022); European Commission, Directorate-General for Education, Youth, Sport and Culture, Kruger, T., Mohamedaly, A., Muller, V. et al., Greening the Creative Europe Programme – Final report (2023).

7.^Henceforth, for sake of brevity, we will refer to the Directorate-General for the Arts by use of the official acronym DGARTES.

8.^With reference to grants received in the years 2021 and 2022.

9.^As already mentioned, the pre-defined population were the 594 organisations which were receiving grants from DGARTES in the years 2021 and 2022.

10.^In this context, automatic renewal means that the funded organisations can, upon evaluation, renew their 4-year funding without having to write and re-submit an application.

11.^Throughout this paper, respondents (R) to the survey and interviewees (IT) will be identified by a fixed number attributed to them during the process of anonymisation.

12.^To increase accessibility and obtain a higher response-rate, these open-ended questions could be answered either in writing or by recording an audio file, up to 5 min in length.

13.^ https://www.culturedeclares.org/

14.^This was also suggested in an independent analysis of the survey’s results, carried out in the context of the Post-Graduate Programme in Arts Management and Sustainability at the Faculty of Arts and Humanities in the University of Coimbra. A group of students were given the opportunity to comment on a partial set of research data, in the framework of a Knowledge Transfer Experiment, while following a dedicated Code of Ethics.

15.^The obstacles that culture professionals identify in their process to become more sustainable will be the subject of a forthcoming paper in the context of the GREENARTS. Green Production - Performing Arts in Transition research project, which is being developed by CEIS20 – Centre for Interdisciplinary Research at the University of Coimbra, funded by FCT - 2022.01609.PTDC.

16.^ https://www.thelocal.es/20230302/why-are-there-so-few-trains-between-spain-and-portugal

17.^Thanks to Ana Carvalhosa, producer and student of our Post-Graduate Programme in Arts Management and Sustainability, for the statement.

18.^This is part of a scene of Nanni Moretti’s 1989 film Palombela Rossa, in which the author/actor almost hits a journalist while shouting: Le parole sono importanti! after she insistently questioned him using foreign words. I thank artist Paula Diogo for the reference.

19.^Author’s interview to Rogério Nuno Costa (Rodrigues, 2024).

References

1

Biggs R. Preiser R. de Vos A. Schlüter M. Maciejewski K. Clements H. (2021). The routledge handbook of research methods for social-ecological systems. 10.4324/9781003021339

2

Boncori I. (2023). Researching and writing differently. 1st ed. Bristol, United Kingdom: Bristol University Press, Policy Press. 10.2307/j.ctv3405pnh

3

Caust J. (2017). The continuing saga around arts funding and the cultural wars in Australia. Int. J. Cult. Policy, 1–15. 10.1080/10286632.2017.1353604

4

Demos T. J. (2016). Decolonizing nature. Contemporary art and the politics of ecology. London, United Kingdom: Sternberg Press.

5

Dragisevic Sesic M. (2021). Cultural management from theory to practice.

6

Elfving T. (2020). Residencies and future cosmopolitics.

7

Freeth R. Drimie S. (2016). Participatory Scenario Planning: FromScenario “Stakeholders” to Scenario “Owners”, Environment: science and policy for sustainable development58:4, 32–43. 10.1080/00139157.2016.1186441

8

Grove Ditlevsen M. (2012). Revealing corporate identities in annual reports. Corp. Commun. An Int. J.17, 379–403. 10.1108/13563281211253593

9

Huber M. T. (2022). Climate change as class war: building socialism on a warming planet. Brooklyn, NY, United States: Verso.

10

Janssens J. Fraioli M. (2022). Perform Europe_Results of the mapping and analysis.

11

Klein N. (2015). This changes everything: capitalism vs. The climate paperback. New York, United States: Simon and Schuster.

12

Kruger T. Feifs T. (2023). Greening of the creative Europe Programme creative Europe Programme greening strategy. 10.2766/667565

13

Krumpal I. (2013). Determinants of social desirability bias in sensitive surveys: a literature review. Qual. Quantity47 (4), 2025–2047. 10.1007/s11135-011-9640-9

14

Lalvani S. (2023). The ultimate cookbook for cultural managers - the EU green deal and live performance organisations. EFA- Eur. Festivals Assoc.

15

Malm A. (2016). Fossil capital: the rise of steam power and the roots of global warming. Brooklyn, NY, United States: Verso.

16

Maxwell J. A. (2005). Research design an interactive approach.

17

Morton T. (2013). Hyperobjects: philosophy and ecology after the end of the world. Minneapolis, United States: University of Minnesota Press. Available at: http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.5749/j.ctt4cggm7 (Accessed September 23, 2022).

18

Power K. (2021). “Sustainability” and the performing arts: discourse analytic evidence from Australia. Poetics89, 101580. Elsevier. 10.1016/j.poetic.2021.101580

19

Ribeiro M. C. (2009). “Between Europe and the atlantic: Portugal as semi-periphery,” in Prospettive degli Studi culturali. Editors AvelliniL.BenvenutiG.MichelacciL.SberlatiF. (Città di Castello, Italy: I Libri di Emil), 163–179.

20

Rodrigues V. (2024). Creative production and management - modus operandi. Routledge: Routledge Advances in Theatre & Performance Studies. ISBN 9781032565330.

21

Rodrigues V. Matos de Oliveira F. Ventura A. (2024) “Part For the whole,” in Report of the survey “ecological and sustainable practices in the performing arts in Portugal. Coimbra: Centre of Interdisciplinary Studies.

22

Rodrigues V. Ventura A. (2024). Embracing ambivalence: responsibility discourses around “greening” the performing arts. Ann. Leis. Res., 1–16. 10.1080/11745398.2024.2358765

23

Rodríguez G. L. (2021). Open letter to jérôme Bel. Available at: https://e-tcetera.be/open-letter-to-jerome-bel/ (Accessed March 17, 2022)

24

Taxopoulou I. (2023). Sustainable theatre: theory, context, practice. 1st ed. London, United Kingdom: Bloomsbury Publishing.

25

Tengö M. Brondizio E. S. Elmqvist T. Malmer P. Spierenburg M. (2014). Connecting diverse knowledge systems for enhanced ecosystem governance: the multiple evidence base approach, 579–591. AMBIO 43.

26

Theatre Green Book (2021). The theatre green Book.Part 1: sustainable productions. London, United Kingdom: Buro Happold and Renew Theatre. Available at: https://theatregreenbook.com/ (Accessed September 12, 2023).

27

The Shift Project. (2021). Décarbonons la culture! Dans le Cadre du plan de transformation de l´économie Française.

28

Torrens X. (2021). “Políticas de innovación abierta: estratégias de nueva gestión cultural,” in La innovación en la gestión de la cultura. Reflexiones y experiencias. Editors BonetL.González-PiñeroM. (Barcelona, Spain: Edicions de la Universitat de Barcelona).

29

Vries G. de (2021). To make the silos dance: mainstreaming culture into EU policy. Belgium, Brussels: European Cultural Foundation.

Summary

Keywords

arts management, green transition, sustainability, cultural policies, performing arts

Citation

Rodrigues V (2024) Greening our future: cultural policy and the ecological imperative. Eur. J. Cult. Manag. Polic. 14:12707. doi: 10.3389/ejcmp.2024.12707

Received

18 January 2024

Accepted

28 October 2024

Published

21 November 2024

Volume

14 - 2024

Updates

Copyright

© 2024 Rodrigues.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Vânia Rodrigues, vania.rodrigues@uc.pt

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.