Abstract

Introduction: The current literature has not yet provided a definitive conclusion on the best emergency groin hernia repair. The aim of this study was first to compare the short and long-term outcomes between open preperitoneal and anterior approach in emergency groin hernia repair and second to identify risk factors for postoperative complications, mortality, and recurrence.

Materials and Methods: This retrospective cohort study included patients who underwent emergency groin hernia repair between January 2010 and December 2018. Short and long-term outcomes were analyzed comparing approach and repair techniques. The predictors of complications and mortality were investigated using multivariate logistic regression. Cox regression multivariate analysis were used to explore risk factors of recurrence.

Results: A total of 316 patients met the inclusion criteria. The most widely used surgical techniques were open preperitoneal mesh repair (34%) and mesh plug (34%), followed by Lichtenstein (19%), plug and patch (7%) and tissue repair (6%). Open preperitoneal mesh repair was associated with lower rates of recurrence (p = 0.02) and associated laparotomies (p < 0.001). Complication and 90-day mortality rate was similar between the techniques. Multivariable analysis identified patients aged 75 years or older (OR, 2.08; 95% CI, 1.14–3.80; p = 0.016) and preoperative bowel obstruction (OR, 2.11; 95% CI, 1.20–3.70; p = 0.010) as risk factors for complications and Comprehensive Complication Index ≥26.2 as risk factor for 90-day mortality (OR, 44.76; 95% CI, 4.51–444.59; p = 0.01). Female gender was the only risk factor for recurrence.

Conclusion: Open preperitoneal mesh repair may be superior to other techniques in the emergency setting, because it can avoid the morbidity of associated laparotomies, with a lower long-term recurrence rate.

Introduction

Nowadays the optimal surgical technique in emergency groin hernia repair remains controversial [1]. Open anterior, open posterior (preperitoneal) and laparoscopic approach with mesh in selected patients has been used safely and effectively [2–5]. However, the evidence is limited, and the choice of a particular approach seems to be based on the criteria and experience of the surgeon in charge [1]. A low-quality randomized study has reported benefits of the open preperitoneal approach in terms of lower incidence of second incisions compared to open anterior approach (Lichtenstein technique) [6]. Nevertheless, there is very scarce data evaluating the short and long-term results of the preperitoneal access in the emergency setting and the potential benefits of this technique remains unknown [6–8].

The primary aim of this study was to compare the short and long-term outcomes between open preperitoneal and open anterior approach in emergency groin hernia repair. Secondarily to identify risk factors for postoperative complications, mortality, and recurrence.

Materials and Methods

Patients and Definitions

This is a retrospective single-center cohort study of all adult patients who underwent emergency groin hernia repair for incarceration or strangulation at Vall d´Hebron University Hospital between January 2010 and December 2018, who were identified from a prospectively maintained database of the Abdominal Wall Surgery Unit of the Surgery Department of our hospital. Emergency groin hernia repair was defined as inguinal or femoral hernia repaired on an emergency basis as a consequence of acute incarceration or strangulation. Incarceration was defined as the inability to reduce the hernia mass into the abdomen and strangulation was defined by the evidence of compromised blood supply to herniated tissues according to the International Guidelines for the management of groin hernia [1]. Patients under 18 years and those who underwent elective surgery after manual or spontaneous reduction of the hernia content were excluded. The data was completed through a retrospective review from medical and surgical records. Data collected included: demographic and clinical information, operative details, short and long-term outcomes measures.

Demographic and Clinical Information

Age, gender, body mass index (BMI), American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) class, Charlson score [9], cardiovascular disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, chronic nephropathy, liver cirrhosis, ascites, neurocognitive disorders, diabetes, inmunosupression and smoking status were collected. Clinical and radiological evidence of preoperative bowel obstruction and duration of incarceration were included. The duration of incarceration was defined as the time elapsed from the start of incarceration referred by the patient until was admitted in the emergency area. Hernia variables included hernia side, type (indirect, direct, femoral, “pantaloon” and sliding) and hernia content.

Operative Information

The surgical approach was classified as open anterior or open preperitoneal. An open transinguinal repair without entering the preperitoneal space using a tissue or mesh technique were considered an anterior approach. An open posterior access of the preperitoneal space without entering the inguinal canal anteriorly and with enough exposure of the Bogros space [10] to allow hernia repair with or without placement of a prosthesis were considered a preperitoneal approach. Repair techniques were categorized as: Lichtenstein, plug and patch, mesh plug, tissue repair and open preperitoneal mesh repair.

In cases when the surgeon´s choice was to perform an open preperitoneal approach, a transverse abdominal incision (8–10 cm in length) was made about two fingerbreadths above the symphysis pubis and two fingers outside the midline was performed. The dissection was carried successively through the skin, subcutaneous tissue, anterior rectus sheath and the oblique muscles aponeurosis (the transverse fascial incision was made the same length as the skin incision). The rectus muscle was retracted medially, and the transversalis fascia was incised to expose the hernia sac. The inferior epigastric vessels were divided as needed. The peritoneum was opened, and hernia contents were delivered, inspected, and reduced. In cases where an intestinal resection and anastomosis was required, it was performed through same incision. The peritoneum was closed after dissection of the vas and vessels off the hernia sac. By retracting the pelvis peritoneum and preperitoneal fat away from the posterior inguinal wall, direct and indirect as well as femoral hernias were recognized. The next step was the placement of the prosthesis. A mesh of polypropylene with minimum size 15 × 15 cms was used to completely cover and overlap the myopectineal orifice. The mesh was anchored, using one stitch of 2-0 synthetic absorbable monofilament to the Cooper´s ligament. A slit was made in the lateral border of the mesh to accommodate the spermatic cord. After spread of mesh prosthesis, layers were closed anatomically.

Following the definitions described above, the patients were grouped according to repair approach in open anterior and open posterior, and according to repair techniques in tissue repair, Lichtenstein, plug and patch, mesh plug, and open preperitoneal mesh repair. The different characteristics of the patients were compared first, between open anterior and open posterior groups, and second, between repair techniques groups.

Other operative details were collected: tissue or mesh repair, bowel resection, anesthesia type, intraoperative complications defined as visceral (i.e., intestinal), vascular (i.e., deep epigastric vessels or femoral vessels) and/or urinary bladder injuries. Midline laparotomy if needed was also collected. Type of surgical wounds were defined according to CDC classification [11]. Clean-contaminated wounds were defined as those in which the alimentary, genital, or urinary tract were entered under controlled conditions and without unusual contamination. Contaminated wounds were those in which there were major interruptions in sterile technique or significant spills from the gastrointestinal tract and incisions in which acute non-purulent inflammations were found.

Broad spectrum antibiotic are given systematically in emergency groin hernia repair and nasogastric tube decompression in cases of bowel obstruction. Anesthesia type was decided by the anesthesiologist. Surgical approach and repair technique were the surgeon´s choice. In cases of anterior approach with bowel resection needs (ischemic) the resection was done via inguinal incision or doing a midline infraumbilical laparotomy incision. In cases of open preperitoneal access the resection was done through same incision.

Outcomes Definition and Follow-Up

Short- and long-term outcomes were compared according to the types of approach and repair techniques.

Short-term outcomes (within postoperative 90 days) evaluated were: length of hospital stay in days (admission-discharge), reoperations rate (not related to recurrences), mortality within 90 days of surgery and postoperative complications. Postoperative complication was defined as any condition that could prolong the length hospital stay or impact the outcomes. Complications were categorized according Clavien-Dindo grading system [12] and was measure using the Comprehensive Complication Index (CCI®, University of Zurich, Zurich, Switzerland) [13].

Long-term outcomes (after postoperative 90 days) evaluated were: recurrence and chronic postoperative inguinal pain. Recurrence was considered after physical examination by the surgeon, review of operative notes reporting repairs of recurrent ipsilateral hernia, or by telephone interviews with the patient using the Ventral Hernia Recurrence Inventory (VHRI) [14]. VHRI is a patient reported outcomes tool, which is considered an accurate method for evaluating recurrence of ventral hernia [15] and validated for inguinal hernia [14]. Chronic postoperative inguinal pain was defined as pain persisting continuously or intermittently for more than 3 months after surgery [16]. Chronic postoperative inguinal pain was assessed by telephone interview using the last question of the VHRI questionnaire: “Do you have pain or other physical symptoms at the site?”. Any positive responses to VHRI prompted a follow-up request for a physical exam. For those patients who did not respond to the follow up telephone interview or call, the last postoperative face-to-face visit was considered as the last follow-up date.

Routinely a follow-up visit was made 2 weeks after hospital discharge and depending on the presence of postoperative complications, more face-to-face visits were scheduled. To assess the presence of recurrence and chronic postoperative pain, telephone interviews were conducted at the time of this study.

Further analysis were performed to determine risk factors for postoperative complications, 90-day mortality and recurrence.

Statistical Analysis

Continuous variables were presented as median and interquartile ranges (IQRs) and compared by using the Mann-Whitney U test. Categorical variables were presented as counts and percentages and compared by Chi-square test of Fisher´s exact test, when indicated. Two logistic regression models were built, one using postoperative complications as the outcome, and other using 90-day mortality. Cox regression multivariate analysis were used to explore risk factors of recurrence. Covariates included in the models were based on clinical consensus and according to significance in the univariate analysis (p < 0.1). The results of complications and 90-day mortality are presented as odds ratios with 95% confidence intervals and recurrence are presented as hazard ratio with 95% confidence intervals. Cumulative recurrence rate was estimated by the Kaplan-Meier method and tested for significance with the log-rank test. A value of p < 0.05 was considered significant. SPSS (IBMS SPSS Statistics 23) was used for statistical analysis.

Results

Patients

A total of 316 patients underwent emergency groin hernia repair at our institution were included. All the operations were performed through an open approach, of which 206 (65.2%) underwent an anterior approach and 110 (34.8%) an open preperitoneal approach. Mesh repair was performed in 296 patients (93.67%) and 20 patients (6.33%) underwent tissue repair (3 patients following preperitoneal approach and 17 anterior approach). The repair techniques used were Lichtenstein in 61 (19.3%) patients, plug and patch in 21 (6.6%), mesh plug in 107 (33.9%), preperitoneal mesh in 107 (33.9%) and tissue repair in 20 (6.3%) patients. The tissue repair techniques used were Bassini-Kirschner in 9 patients, Bassini in 4, Lotheissen-McVay in 4, Nyhus in 2, and Shouldice in 1 patient. In our series there were no bilateral hernia repairs. The characteristics of patients regarding type of approach are shown in Table 1 and regarding type of technique in Table 2.

TABLE 1

| Variables | Total (n = 316) | Anterior approach (n = 206) | Preperitoneal approach (n = 110) | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (yr)[median (IQR)] | 78 (69–85) | 77.5 (69–84) | 80 (70–87) | 0.085 |

| Gender [n, (%)] | 0.782 | |||

| Male | 147 (46.52) | 97 (47.09) | 50 (45.45) | |

| Female | 169 (53.48) | 109 (52.91) | 60 (54.55) | |

| BMI (kg/m2) [median (IQR)] | 24.8 (22.3–27.6) | 25.1 (23–28) | 23.7 (21.6–26.4) | 0.010 |

| ASA score | 0.582 | |||

| I/II [n, (%)] | 179 (56.60) | 119 (57.77) | 60 (54.55) | |

| III/IV [n, (%)] | 137 (43.35) | 87 (42.23) | 50 (45.45) | |

| Charlson score [median (IQR)] | 5 (4–6) | 5 (4–6) | 5 (4–6) | 0.800 |

| Previous abdominal surgery [n, (%)] | 137 (43.35) | 90 (43.69) | 47 (42.73) | 0.869 |

| Comorbidity [n, (%)] | 259 (81.96) | 168 (81.55) | 91 (82.73) | 0.796 |

| Cardiovascular disease [n, (%)] | 223 (70.57) | 142 (68.93) | 81 (73.64) | 0.382 |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease [n, (%)] | 65 (20.57) | 43 (20.87) | 22 (20.00) | 0.855 |

| Chronic nephropathy [n, (%)] | 37 (11.71) | 21 (10.19) | 16 (14.55) | 0.252 |

| Liver cirrhosis [n, (%)] | 10 (3.16) | 9 (4.37) | 1 (0.91) | 0.094 |

| Ascites [n, (%)] | 10 (3.16) | 8 (3.88) | 2 (1.82) | 0.318 |

| Neurocognitive disorders [n, (%)] | 48 (15.19) | 30 (14.56) | 18 (16.36) | 0.671 |

| Diabetes [n, (%)] | 38 (12.03) | 26 (12.62) | 12 (10.91) | 0.656 |

| Immunosuppression [n, (%)] | 18 (5.70) | 12 (5.83) | 6 (5.45) | 0.892 |

| Active smoking [n, (%)] | 26 (8.23) | 15 (7.28) | 11 (10) | 0.402 |

| Comorbidity more than one [n, (%)] | 167 (52.85) | 109 (52.91) | 58 (52.73) | 0.975 |

| Hernia type [n, (%)] | 0.757 | |||

| Inguinal indirect | 76 (24.05) | 46 (22.33) | 30 (27.27) | |

| Inguinal direct | 47 (14.87) | 32 (15.53) | 15 (13.64) | |

| Femoral | 179 (56.65) | 118 (57.28) | 61 (55.45) | |

| Others | 14 (4.43) | 10 (4.85) | 4 (3.64) | |

| Hernia side [n, (%)] | 0.210 | |||

| Right | 189 (59.81) | 118 (57.28) | 71 (64.55) | |

| Left | 127 (40.19) | 88 (42.72) | 39 (35.45) | |

| Recurrent hernia [n, (%)] | 56 (17.72) | 36 (17.48) | 20 (18.18) | 0.876 |

| Hernia sac contents [n, (%)] | 0.194 | |||

| Omentum | 45 (14.24) | 31 (15.05) | 14 (12.73) | |

| Small bowel | 194 (61.39) | 124 (60.19) | 70 (63.64) | |

| Colon | 23 (7.28) | 13 (6.31) | 10 (9.09) | |

| Bladder | 3 (0.95) | 1 (0.49) | 2 (1.82) | |

| Appendix | 4 (1.27) | 2 (0.97) | 2 (1.82) | |

| Other | 18 (5.70) | 10 (4.85) | 8 (7.27) | |

| Not reported | 8 (2.53) | 6 (2.91) | 2 (1.82) | |

| Reported as empty at the moment of opening | 21 (6.65) | 19 (9.22) | 2 (1.82) | |

| Necrotic contents [n, (%)] | 81 (25.63) | 46 (22.33) | 35 (31.82) | 0.066 |

| Preoperative bowel obstruction [n, (%)] | 165 (52.22) | 101 (49.03) | 64 (58.18) | 0.121 |

| Duration of incarceration [median (IQR)] | 24 (11–72) | 24 (10–72) | 24.5 (12–72) | 0.833 |

| Grade of contamination [n, (%)] | 0.975 | |||

| Clean | 235 (74.37) | 154 (74.76) | 81 (73.64) | |

| Clean/contaminated | 64 (20.25) | 41 (19.90) | 23 (20.91) | |

| Contaminated | 17 (5.38) | 11 (5.34) | 6 (5.45) | |

| Bowel resection performed [n, (%)] | 66 (20.89) | 38 (18.45) | 28 (25.45) | 0.144 |

| Type of anesthesia [n, (%)] | 0.006 | |||

| Spinal | 148 (46.84) | 110 (53.40) | 38 (34.55) | |

| Local alone | 7 (2.22) | 4 (1.94) | 3 (2.73) | |

| General | 161 (50.95) | 92 (44.66) | 69 (62.73) | |

| Required midline laparotomy [n, (%)] | 24 (7.59) | 19 (9.22) | 5 (4.55) | 0.135 |

| Intraoperative complications [n, (%)] | 17 (5.38) | 10 (4.85) | 7 (6.36) | 0.571 |

| Postoperative complications [n (%)] | 152 (48.1) | 99 (48.06) | 53 (48.18) | 0.983 |

| Comprehensive complication index [median (IQR)] | 8.7 (0–29.6) | 8.7 (0–29.6) | 8.7 (0–29.6) | 0.856 |

| Clavien Dindo classification of postoperative complications [n (%)] | 0.971 | |||

| None | 178 (56.33) | 115 (55.83) | 63 (57.27) | |

| I/II | 91 (28.80) | 59 (28.64) | 32 (29.09) | |

| III/IV | 26 (8.23) | 18 (8.74) | 8 (7.27) | |

| V | 21 (6.65) | 14 (6.80) | 7 (6.36) | |

| Reoperation [n, (%)] | 13 (4.11) | 9 (4.37) | 4 (3.64) | 0.755 |

| Length of stay (days) [median (IQR)] | 4 (2–7.5) | 4 (2–7) | 4 (2–8) | 0.391 |

| Recurrence [n, (%)] | 27 (8.5) | 23 (7.3) | 4 (1.3) | 0.023 |

| Chronic postoperative inguinal pain [n, (%)] | 7 (2.2) | 5 (2.4) | 2 (1.8) | 0.818 |

Patient Characteristics of Study Population according to the repair approach.

TABLE 2

| Variables | Total (n = 316) | Lichtenstein (n = 61) | Plug and patch (n = 21) | Mesh plug (n = 107) | Tissue repair (n = 20) | Preperitoneal mesh (n = 107) | p Values |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (yr)[median (IQR)] | 78 (69–85) | 74 (67–83) | 78 (73–81) | 78 (70–84) | 80.5 (71–86) | 81 (70–87) | 0.188 |

| Gender [n, (%)] | < 0.001 | ||||||

| Male | 147 (46.52) | 43 (70.49) | 13 (61.90) | 36 (33.64) | 7 (35.00) | 48 (44.86) | |

| Female | 169 (53.48) | 18 (29.51) | 8 (38.10) | 71 (66.36) | 13 (65.00) | 59 (55.14) | |

| BMI (kg/m2) [median (IQR)] | 24.8 (22.3–27.6) | 26.6 (24.3–29) | 25.1 (22.7–29.3) | 24.9 (22.3–27.2) | 23.35 (22.3–27.1) | 23.85 (21.75–26.4) | 0.004 |

| ASA score | 0.843 | ||||||

| I/II [n, (%)] | 179 (56.65) | 38 (62.30) | 13 (61.90) | 59 (55.14) | 11 (55.00) | 58 (54.21) | |

| III/IV [n, (%)] | 137 (43.35) | 23 (37.70) | 8 (38.10) | 48 (44.86) | 9 (45.00) | 49 (45.79) | |

| Charlson score [median (IQR)] | 5 (4–6) | 5 (4–7) | 6 (4–8) | 5 (4–6) | 4 (4–6) | 5 (4–6) | 0.417 |

| Previous abdominal surgery [n, (%)] | 137 (43.35) | 26 (42.62) | 12 (57.14) | 49 (45.79) | 5 (25.00) | 45 (42.06) | 0.318 |

| Comorbidity [n, (%)] | 259 (81.96) | 52 (85.25) | 19 (90.48) | 84 (78.5) | 14 (70.00) | 90 (84.11) | 0.330 |

| Cardiovascular disease [n, (%)] | 223 (70.57) | 44 (72.13) | 17 (80.95) | 70 (65.42) | 12 (60.00) | 80 (74.77) | 0.341 |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease [n, (%)] | 65 (20.57) | 13 (21.31) | 5 (23.81) | 22 (20.56) | 3 (15.00) | 22 (20.56) | 0.970 |

| Chronic nephropathy [n, (%)] | 37 (11.71) | 6 (9.84) | 3 (14.29) | 8 (7.48) | 4 (20.00) | 16 (14.95) | 0.329 |

| Liver cirrhosis [n, (%)] | 10 (3.16) | 2 (3.28) | 0 (0) | 6 (5.61) | 1 (5.00) | 1 (0.93) | 0.316 |

| Ascites [n, (%)] | 10 (3.16) | 2 (3.28) | 0 (0) | 5 (4.67) | 1 (5.00) | 2 (1.87) | 0.683 |

| Neurocognitive disorders [n, (%)] | 48 (15.19) | 8 (13.11) | 6 (28.57) | 15 (14.02) | 1 (5.00) | 18 (16.82) | 0.280 |

| Diabetes [n, (%)] | 38 (12.03) | 12 (19.67) | 2 (9.52) | 12 (11.21) | 0 (0) | 12 (11.21) | 0.174 |

| Inmunosupression [n, (%)] | 18 (5.7) | 2 (3.28) | 2 (9.52) | 7 (6.54) | 2 (10.00) | 5 (4.67) | 0.685 |

| Active smoking [n, (%)] | 26 (8.23) | 4 (6.56) | 4 (19.05) | 7 (6.54) | 1 (5.00) | 10 (9.35) | 0.362 |

| Comorbidity more than one [n, (%)] | 167 (52.85) | 30 (49.18) | 15 (71.43) | 55 (51.4) | 10 (50.00) | 57 (53.27) | 0.493 |

| Hernia type [n, (%)] | < 0.001 | ||||||

| Inguinal indirect | 76 (24.05) | 29 (47.54) | 8 (38.10) | 5 (4.67) | 5 (25.00) | 29 (27.10) | |

| Inguinal direct | 47 (14.87) | 18 (29.51) | 5 (23.81) | 7 (6.54) | 3 (15.00) | 14 (13.08) | |

| Femoral | 179 (56.65) | 8 (13.11) | 6 (28.57) | 94 (87.85) | 11 (55.00) | 60 (56.07) | |

| Others | 14 (4.43) | 6 (9.84) | 2 (9.52) | 1 (0.93) | 1 (5.00) | 4 (3.74) | |

| Hernia side [n, (%)] | 0.029 | ||||||

| Right | 189 (59.81) | 28 (45.90) | 17 (80.95) | 61 (57.01) | 13 (65.00) | 70 (65.42) | |

| Left | 127 (40.19) | 33 (54.10) | 4 (19.05) | 46 (42.99) | 7 (35.00) | 37 (34.58) | |

| Recurrent hernia [n, (%)] | 56 (17.72) | 12 (19.67) | 4 (19.05) | 16 (14.95) | 4 (20.00) | 20 (18.69) | 0.926 |

| Hernia sac contents [n, (%)] | 0.031 | ||||||

| Omentum | 45 (14.24) | 9 (14.75) | 0 (0) | 21 (19.63) | 2 (10.00) | 13 (12.15) | |

| Small bowel | 194 (61.39) | 29 (47.54) | 19 (90.48) | 66 (61.68) | 10 (50.00) | 70 (65.42) | |

| Colon | 23 (7.28) | 6 (9.84) | 1 (4.76) | 3 (2.80) | 4 (20.00) | 9 (8.41) | |

| Bladder | 3 (0.95) | 1 (1.64) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 2 (1.87) | |

| Appendix | 4 (1.27) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 2 (1.87) | 1 (5.00) | 1 (0.93) | |

| Other | 18 (5.70) | 3 (4.92) | 1 (4.76) | 5 (4.67) | 1 (5.00) | 8 (7.48) | |

| Not reported | 8 (2.53) | 3 (4.92) | 0 (0) | 3 (2.80) | 0 (0) | 2 (1.87) | |

| Reported as empty at the moment of opening | 21 (6.65) | 10 (16.39) | 0 (0) | 7 (6.54) | 2 (10.00) | 2 (1.87) | |

| Necrotic contents [n, (%)] | 81 (25.63) | 7 (11.48) | 1 (4.76) | 31 (28.97) | 9 (45.00) | 33 (30.84) | 0.002 |

| Preoperative bowel obstruction [n, (%)] | 165 (52.22) | 25 (40.98) | 12 (57.14) | 53 (49.53) | 12 (60.00) | 63 (58.88) | 0.200 |

| Duration of incarceration [median (IQR)] | 24 (11–72) | 16 (11–48) | 10 (6–48) | 47 (12–72) | 41 (18.5–96) | 24 (12–72) | 0.024 |

| Grade of contamination [n, (%)] | 0.050 | ||||||

| Clean | 235 (74.37) | 51 (83.61) | 18 (85.71) | 75 (70.09) | 11 (55.00) | 80 (74.77) | |

| Clean/contaminated | 64 (20.25) | 8 (13.11) | 3 (14.29) | 27 (25.23) | 5 (25.00) | 21 (19.63) | |

| Contaminated | 17 (5.38) | 2 (3.28) | 0 (0) | 5 (4.67) | 4 (20.00) | 6 (5.61) | |

| Bowel resection performed [n, (%)] | 66 (20.89) | 6 (9.84) | 1 (4.76) | 26 (24.3) | 8 (40.00) | 25 (23.36) | 0.010 |

| Type of anesthesia [n, (%)] | 0.016 | ||||||

| Spinal | 148 (46.84) | 36 (59.02) | 15 (71.43) | 53 (49.53) | 8 (40.00) | 36 (33.64) | |

| Local alone | 7 (2.22) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 3 (2.80) | 1 (5.00) | 3 (2.80) | |

| General | 161 (50.95) | 25 (40.98) | 6 (28.57) | 51 (47.66) | 11 (55.00) | 68 (63.55) | |

| Required midline laparotomy [n, (%)] | 24 (7.59) | 3 (4.92) | 2 (9.52) | 8 (7.48) | 7 (35.00) | 4 (3.74) | < 0.001 |

| Intraoperative complications [n, (%)] | 17 (5.38) | 5 (8.2) | 1 (4.76) | 3 (2.8) | 1 (5.00) | 7 (6.54) | 0.618 |

| Postoperative Complications [n (%)] | 152 (48.1) | 26 (42.62) | 10 (47.62) | 53 (49.53) | 11 (55.00) | 52 (48.6) | 0.876 |

| Comprehensive complication index [median (IQR)] | 8.7 (0–29.6) | 8.7 (0–29.6) | 8.7 (0–30.8) | 8.7 (0–26.2) | 60.6 (19.25–100) | 8.7 (0–29.6) | 0.020 |

| Clavien Dindo classification of postoperative complications [n (%)] | 0.297 | ||||||

| None | 178 (56.33) | 38 (62.30) | 11 (52.38) | 59 (55.14) | 9 (45.00) | 61 (57.01) | |

| I/II | 91 (28.80) | 14 (22.95) | 7 (33.33) | 34 (31.78) | 4 (20.00) | 32 (29.91) | |

| III/IV | 26 (8.23) | 6 (9.84) | 2 (9.52) | 8 (7.48) | 2 (10.00) | 8 (7.48) | |

| V | 21 (6.65) | 3 (4.92) | 1 (4.76) | 6 (5.61) | 5 (25.00) | 6 (5.61) | |

| Reoperation [n, (%)] | 13 (4.11) | 2 (3.28) | 1 (4.76) | 6 (5.61) | 0 (0) | 4 (3.74) | 0.803 |

| Length of stay (days) [median (IQR)] | 4 (2–7.5) | 3 (2–6) | 4 (2–7) | 4 (2–8) | 4 (2–9) | 4 (2–8) | 0.891 |

| Recurrence [n, (%)] | 27 (8.5) | 4 (6.6) | 1 (4.8) | 17 (15.9) | 1 (5) | 4 (3.7) | 0.020 |

| Chronic postoperative inguinal pain [n, (%)] | 7 (2.2) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 5 (4.6) | 0 (0) | 2 (1.8) | 0.365 |

Patient Characteristics of Study Population according to the repair technique.

Patients with an anterior approach had a higher BMI and a majority of spinal anesthesia, while the open preperitoneal approach group had a lower BMI (p = 0.01) and more general anesthesia (p = 0.006). However, the clinical relevance is unlikely since the median differences are small. When performing comparisons by the different groups of repair techniques, again the differences can be seemingly meaningful, and the clinical relevance should be considered carefully. A greater number of female patients underwent mesh plug repairs, open preperitoneal and tissue repair, while the Lichtenstein and plug and patch techniques were used more in men (p < 0.001). Patients with higher BMI underwent more frequent Lichtenstein and plug and patch techniques (p = 0.004). Indirect hernias were mostly repaired with Lichtenstein and femoral hernias with mesh plug, open preperitoneal, and tissue repair (p < 0.001). In those patients with the longest incarceration duration, with necrotic contents and in whom an intestinal resection was performed, the most frequently performed techniques were the tissue repair, mesh plug, and open preperitoneal. In the Lichtenstein and plug and patch techniques, there was a greater use of spinal anesthesia with respect to tissue repair, mesh plug, and open preperitoneal where general anesthesia was the most widely used anesthetic technique (p = 0.016). Patients with tissue repair more frequently required the association of a midline laparotomy, while those who underwent an open preperitoneal approach were those who least needed it (p < 0.001).

Postoperative Complications

The overall postoperative complications rate was 48.1% (152/316). There were no significant differences in morbidity between an anterior or open preperitoneal approach (p = 0.983), and between the different repair techniques (p = 0.876). There were no differences between the patients who underwent mesh repair and those with tissue repair (p = 0.523). Patients with major complications (Clavien-Dindo ≥3A) were 47 (14.8%), without significant differences regarding the type of approach (p = 0.971) or repair technique (p = 0.297). There were no differences regarding the CCI® according to the type of approach (p = 0.856); however, by surgical techniques, tissue repair was associated with higher CCI® compared to the other repair techniques (p = 0.02). Surgical reintervention was required by 13 patients for small bowel obstruction (n = 4), intestinal ischemia (n = 2), intra-abdominal abscess (n = 2), wound infection (n = 2), anastomotic leak (n = 1), intestinal perforation (n = 1) and wound hematoma (n = 1). The 90-day mortality was 8.5% (N = 27) and no statistically significant difference was seen between surgical approach (p = 0.799) or repair technique (p = 0.923) groups.

Long-Term Outcomes According to Surgical Approach and Repair Techniques

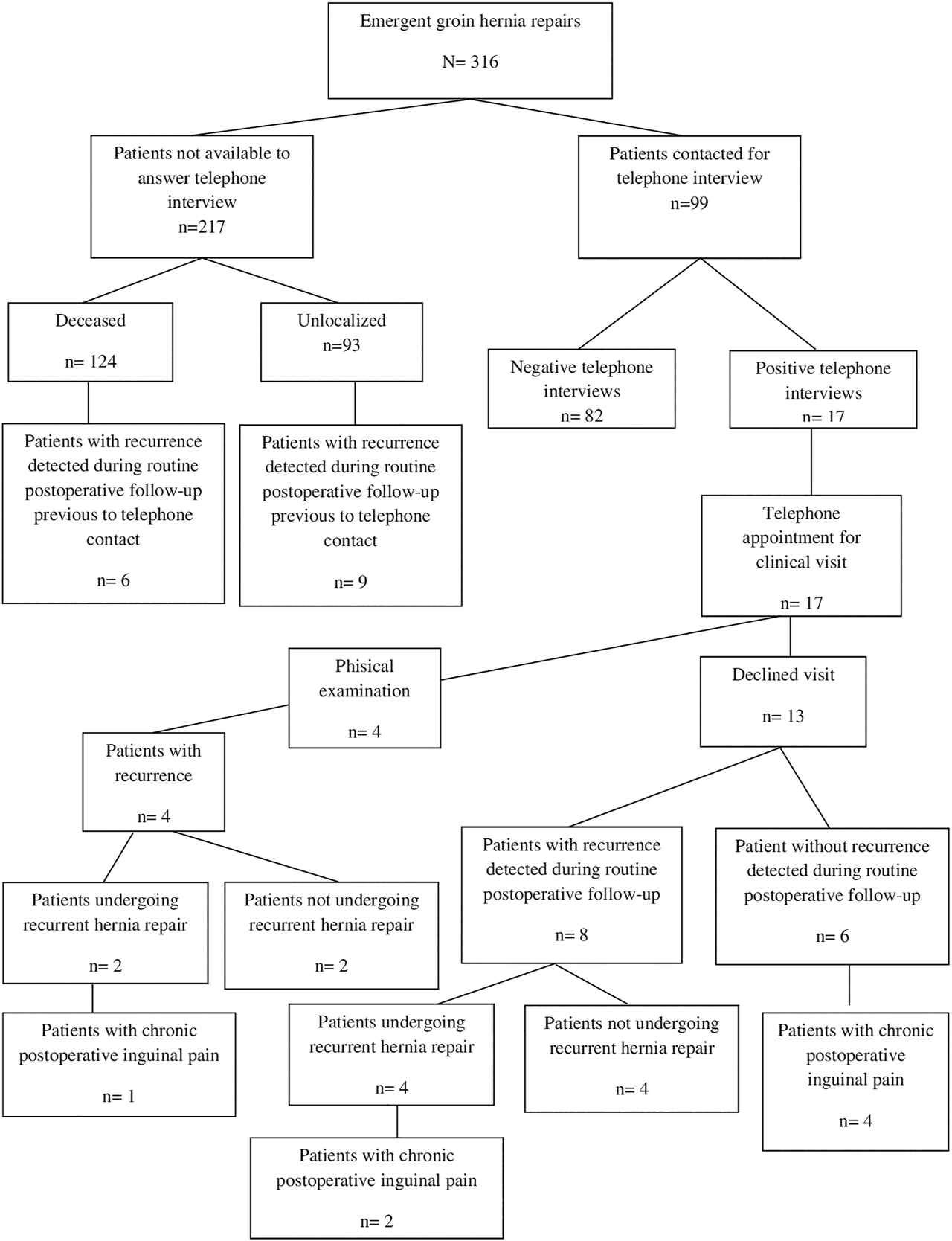

The median follow-up period was 13.31 months (IQR: 0.86–52.93). The recurrence rate of the whole series was 8.5% (n = 27). A total of 20 (74.1%) recurrences appears after femoral hernia repair, 4 (14.8%) in indirect and 3 (11.1%) in direct hernias. There were no differences in recurrence rates between patients who underwent mesh repair and those with tissue repair (p = 1). Figure 1 shows the flow-chart of included patients and long-term outcomes.

FIGURE 1

Flow-chart of study cohort and long-term outcomes.

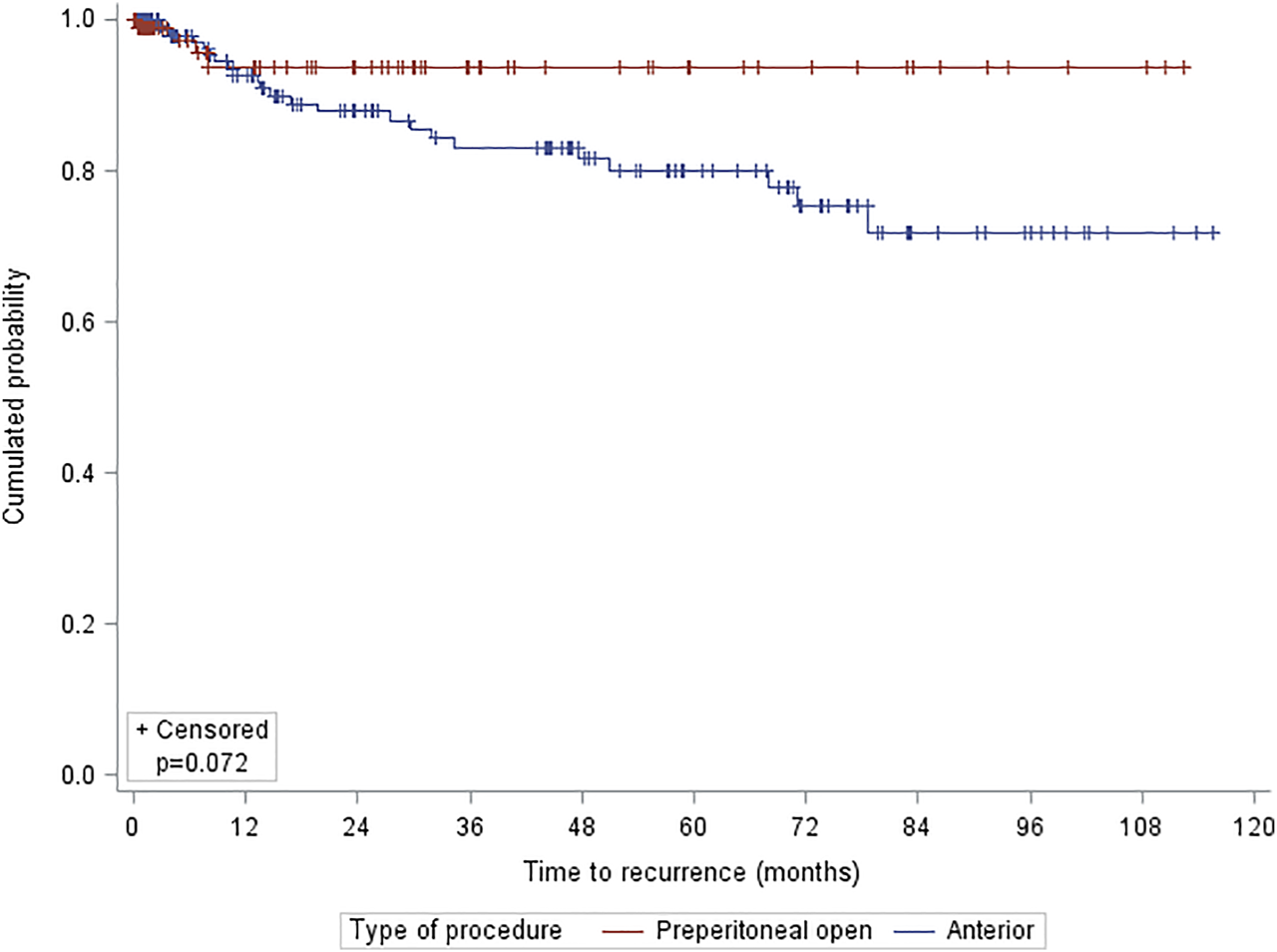

Patients with an open preperitoneal approach had a lower rate of recurrence compared with the anterior approach (p = 0.023). Regarding the cumulative recurrence, there were no differences according to the type of approach (p = 0.072, log rank) (Figure 2).

FIGURE 2

Kaplan-Meier estimates for long-term hernia recurrence by approach.

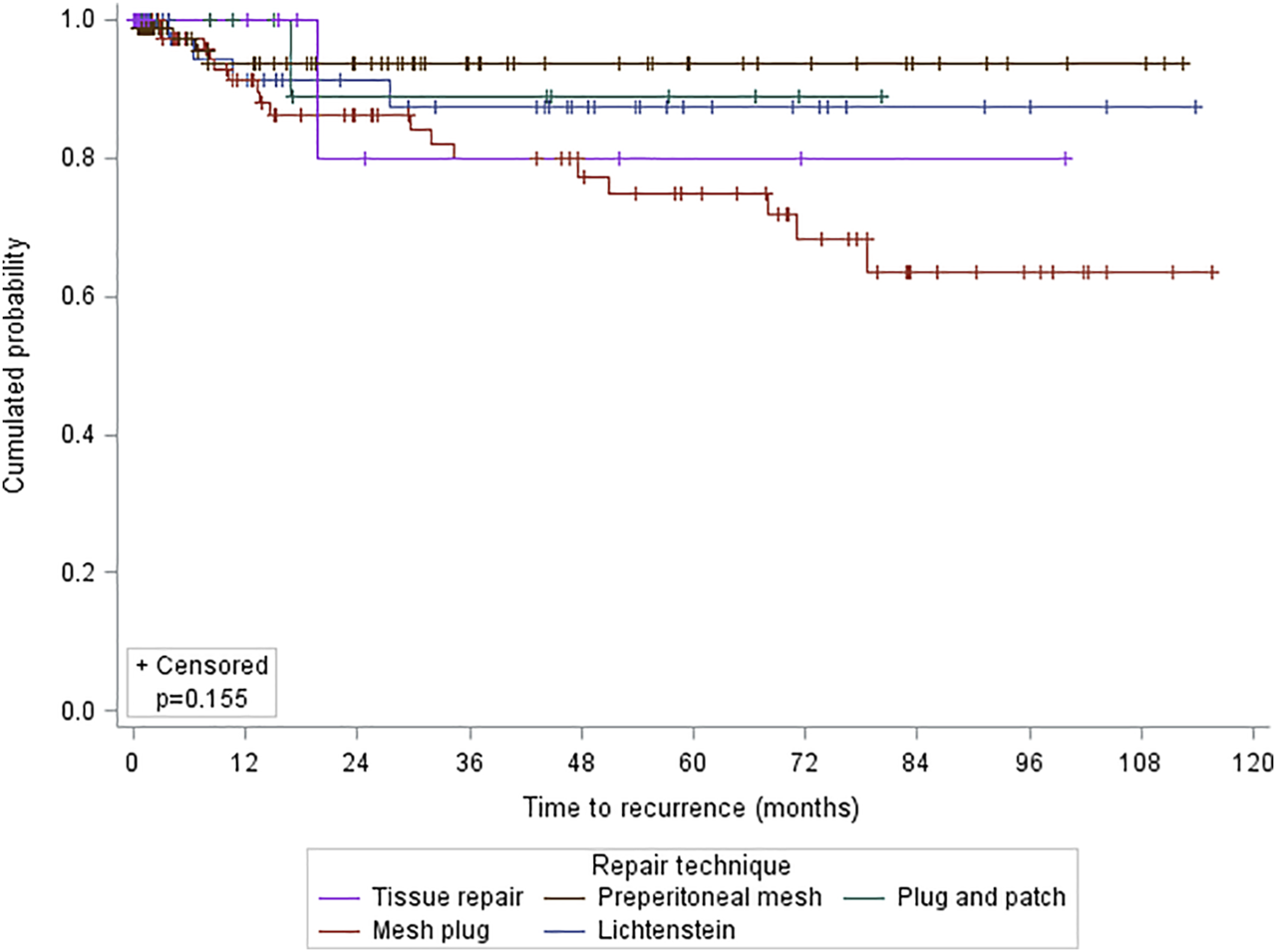

Higher recurrence rate was observed in patients with a mesh plug repair (p = 0.020). Regarding the cumulative recurrence, there were no differences according to the type of technique (p = 0.155, log rank) (Figure 3).

FIGURE 3

Kaplan-Meier estimates for long-term hernia recurrence by technique.

Concerning chronic postoperative inguinal pain, only 99 patients responded to the telephone interview and completed the VHRI questionnaire of them 7 presented chronic postoperative inguinal pain. No significant differences were found according to the type of approach (p = 0.818) or the type of surgical technique (p = 0.363).

Risk Factors of Postoperative Complications

The results of uni- and multivariate analysis of postoperative complications are shown in Table 3. On multivariate analysis ≥75 years of age (OR, 2.08; 95% CI, 1.14–3.80; p = 0.016) and preoperative bowel obstruction (OR, 2.11; 95% CI, 1.20–3.70; p = 0.010) were risk factor for postoperative complications after emergency groin hernia repair.

TABLE 3

| Variables | Univariable analysis | Multivariable analysis | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Complications | Mortality 90 days | Recurrence | Complications | Mortality 90 days | Recurrence | |||||||

| OR (95%CI) | p value | OR (95%CI) | p value | HR (95%CI) | p Value | OR (95%CI) | p Value | OR (95%CI) | p Value | HR (95%CI) | p Value | |

| Patient age (y) | ||||||||||||

| <75 (n = 125) | 1 | <0.001 | 1 | <0.001 | 1 | 0.884 | 1 | 0.016 | 1 | 0.288 | ||

| ≥75 (n = 191) | 3.82 (2.36–6.20) | 9.26 (2.15–39.84) | 1.06 (0.49–2.27) | 2.08 (1.14–3.80) | 3.17 (0.38–26.61) | |||||||

| Gender | ||||||||||||

| Male (n = 147) | 1 | 0.948 | 1 | 0.003 | 1 | 0.005 | 1 | 0.055 | 1 | 0.011 | ||

| Female (n = 169) | 0.99 (0.63–1.53) | 0.27 (0.11–0.67) | 0.32 (0.14–0.71) | 0.21 (0.04–1.03) | 0.35 (0.15–0.78) | |||||||

| BMI | ||||||||||||

| <30 (n = 250) | 1 | 0.445 | 1 | 0.714 | 1 | 0.519 | ||||||

| ≥30 (n = 31) | 0.75 (0.35–1.59) | 1.38 (0.38–4.98) | 0.62 (0.15–2.63) | |||||||||

| ASA score | ||||||||||||

| I/II (n = 179) | 1 | <0.001 | 1 | <0.001 | 1 | 0.955 | 1 | 0.203 | 1 | 0.518 | ||

| III/IV (n = 137) | 2.89 (1.82–4.58) | 4.20 (1.72–10.25) | 1.02 (0.46–2.25) | 1.46 (0.82–2.61) | 0.63 (0.16–2.54) | |||||||

| Charlson score | ||||||||||||

| <3 (n = 28) | 1 | <0.001 | 1 | 0.149 | 1 | 1 | 0.393 | |||||

| ≥3 (n = 288) | 6.34 (2.15–18.74) | ∞ (0.86 - ∞) | 2.86 (0.39–21.14) | 1.74 (0.49–6.18) | ||||||||

| Previous abdominal surgery | ||||||||||||

| Yes (n = 137) | 0.82 (0.52–1.28) | 0.376 | 0.89 (0.40–1.98) | 0.774 | 0.79 (0.36–1.73) | 0.558 | ||||||

| No (n = 179) | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||||||

| Comorbidity | ||||||||||||

| Yes (n = 250) | 3.50 (1.83–6.71) | <0.001 | ∞ (2.02–∞) | 0.007 | 1.92 (0.66–5.59) | 0.23 | ||||||

| No (n = 116) | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||||||

| Cardiovascular disease | ||||||||||||

| Yes (n = 223) | 2.71 (1.63–4.53) | <0.001 | 5.74 (1.33–24.77) | 0.009 | 2.08 (0.83–5.17) | 0.117 | 1.59 (0.80–3.15) | 0.188 | 3.38 (0.33 –34.71) | 0.306 | ||

| No (n = 93) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||||

| COPD | ||||||||||||

| Yes (n = 65) | 1.34 (0.77–2.31) | 0.298 | 2.50 (1.09–5.77) | 0.027 | 1.75 (0.74–4.14) | 0.205 | 2.97 (0.7–11.96) | 0.125 | ||||

| No (n = 251) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||||

| Chronic nephropathy | ||||||||||||

| Yes (n = 37) | 2.87 (1.36–6.04) | 0.004 | 5.71 (2.38–13.70) | <0.001 | 0.67 (0.09–4.98) | 0.698 | 2.16 (0.90–5.18) | 0.083 | 3.58 (0.82–15.66) | 0.090 | ||

| No (n = 279) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||||

| Liver cirrhosis | ||||||||||||

| Yes (n = 10) | 1.64 (0.45–5.94) | 0.444 | 1.0 (0.00–3.80) | 1.000 | 3.67 (1.1–12.25) | 0.034 | 2.39 (0.68–8.36) | 0.173 | ||||

| No (n = 306) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||||

| Diabetes | ||||||||||||

| Yes (n = 38) | 1.23 (0.62–2.42) | 0.551 | 0.91 (0.26–3.17) | 1.000 | 0.51 (0.12–2.14) | 0.354 | ||||||

| No (n = 278) | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||||||

| Comorbidity more than one | ||||||||||||

| Yes (n = 167) | 2.02 (1.29 – 3–17) | 0.002 | 3.43 (1.34–8.74) | 0.007 | 2.07 (0.95–4.51) | 0.069 | 1.51 (0.67–3.41) | 0.323 | ||||

| No (n = 149) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||||

| Femoral hernia | ||||||||||||

| Yes (n = 179) | 0.94 (0.61–1.47) | 0.802 | 0.50 (0.22–1.10) | 0.081 | 1.82 (0.77–4.31) | 0.175 | 1.10 (0.21 – 5–76) | 0.906 | ||||

| No (n = 137) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||||

| Recurrent hernia | ||||||||||||

| Yes (n = 56) | 0.84 (0.47–1.51) | 0.568 | 0.79 (0.26–2.39) | 0.780 | 1.67 (0.71–3.96) | 0.242 | ||||||

| No (n = 260) | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||||||

| Necrotic contents | ||||||||||||

| Yes (n = 81) | 4.83 (2.73–8.53) | <0.001 | 5.98 (2.61–13.69) | <0.001 | 1.90 (0.85–4.24) | 0.118 | 2.75 (0.85–8.92) | 0.093 | 7.04 (0.64–77.34) | 0.111 | ||

| No (n = 235) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||||

| Preoperative bowel obstruction | ||||||||||||

| Yes (n = 165) | 4.61 (2.86–7.41) | <0.001 | 28.06 (3.76–209.53) | <0.001 | 0.64 (0.29–1.39) | 0.260 | 2.11 (1.20–3.70) | 0.010 | 8.00 (0.65–98.56) | 0.105 | ||

| No (n = 151) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||||

| Duration of incarceration | ||||||||||||

| <24 h (n = 124) | 1 | 0.046 | 1 | 0.132 | 1 | 0.105 | 1 | 0.518 | ||||

| ≥24 h (n = 190) | 1.59 (1.01–2.51) | 1.97 (0.81–4.80) | 0.53 (0.24–1.14) | 1.19 (0.70–2.04) | ||||||||

| Bowel resection performed | ||||||||||||

| Yes (n = 66) | 6.98 (3.55–13.71) | <0.001 | 4.91 (2.18–11.06) | <0.001 | 1.37 (0.55–3.39) | 0.502 | 1.79 (0.48–6.74) | 0.388 | 0.32 (0.03–3.14) | 0.325 | ||

| No (n = 250) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||||

| CCI | ||||||||||||

| <26.2 (n = 37) | 1 | <0.001 | 1 | <0.001 | 1 | 0.947 | NA | 44.76 (4.51–444.59) | 0.001 | |||

| ≥26.2 (n = 46) | 0.74 (0.30–1.85) | 81.25 (10.74–614.68) | 1.04 (0.37–2.88) | 1 | ||||||||

| Mesh repair | 0.882 | 0.141 | ||||||||||

| Yes (n = 296) | 1.0 (0.63–1.60) | 0.523 | 0.24 (0.08–0.72) | 0.020 | 1.16 (0.16–8.58) | 0.25 (0.04–1.58) | ||||||

| No (n = 20) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||||

| Type of procedure | ||||||||||||

| Anterior (n = 206) | 1 | 0.983 | 1 | 0.800 | 1 | 0.083 | 1 | 0.107 | ||||

| Preperitoneal open (n = 110) | 4.83 (2.73–8.53) | 1.11 (0.49–2.52) | 0.39 (0.13–1.13) | 0.42 (0.14–1.21) | ||||||||

| Type of mesh repair | ||||||||||||

| Lichtenstein (n = 61) | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||||||

| Plug and patch (n = 21) | 1.22 (0.45–3.31) | 0.691 | 1.50 (0.25–8.85) | 0.654 | 0.74 (0.08–6.67) | 0.792 | ||||||

| Mesh plug (n = 107) | 1.32 (0.70–2.49) | 0.389 | 1.00 (0.28–3.56) | 0.997 | 2.08 (0.7–6.2) | 0.188 | ||||||

| Preperitoneal mesh (n = 107) | 1.27 (0.68–2.40) | 0.456 | 1.31 (0.39–4.44) | 0.666 | 0.63 (0.16–2.51) | 0.510 | ||||||

| Intraoperative complications | ||||||||||||

| Yes (n = 17) | 5.44 (1.53–19.34) | 0.004 | 5.25 (1.69 –16.24) | 0.009 | 0.36 (0.02–6.32) | 0.486 | 4.08 (0.99–16.91) | 0.052 | 1.11 (0.19–6.50) | 0.905 | ||

| No (n = 299) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||||

Univariable and Multivariable Analysis of complications, mortality and recurrence.

Risk Factors of 90-day Mortality

Table 3 shows the results of uni- and multivariate analysis of 90-day mortality. Multivariate analysis identified CCI ≥26.2 (OR, 44.76; 95% CI, 4.51–444.59; p = 0.01) as a risk factor for 90-day mortality after emergency groin hernia repair.

Risk Factors of Recurrence

Table 3 shows the results of uni- and multivariate analysis of recurrence. In the multivariate analysis, only the female gender (HR, 0.35; 95% CI, 0.15–0.78; p = 0.011) was a risk factor for recurrence after emergency groin hernia repair.

Discussion

In the present study significant advantages were identified in the open preperitoneal repair over anterior approach in terms of less need for associated midline laparotomies and lower recurrence rate. In patients in whom potential intestinal resection was more expected (femoral hernia or longer duration of incarceration) the more frequent used techniques were open preperitoneal, mesh plug and tissue repair. Age ≥75 years and preoperative intestinal obstruction were independent factors associated with postoperative complications. CCI ≥26.2 was significantly associated with increased mortality at 90 days and female gender was the factor correlated with hernia recurrence.

Regarding the short-term outcomes, in our series there were no differences between the groups according to surgical approach in terms of postoperative complications or length hospital stay. However, in the comparison by type of technique repair, we observed that tissue repair presented higher CCI® compared to mesh repairs. This higher severity of postoperative complications could be related to the high number of contaminated surgeries, higher frequency of necrotic hernia content and intestinal resections present in the tissue repair group. These findings are consistent with previously published literature and confirm that mesh repairs are safe in the emergency setting [2,3]. On the other hand, in our study preperitoneal mesh repair was associated with fewer midline laparotomies, even though this group had a higher proportion of bowel resections. Similar results were reported by others [5]. In our series the patients were operated on using an extensive preperitoneal approach [7]. Through this extensive approach, it was possible to have access to the peritoneal cavity for the inspection of the herniated content, allowing for comfortable intestinal resections if needed, also being able to have a complete view of the myopectineal orifice and assess other potential hernias, as well as placing a mesh covering the entire area. In our opinion this is an important finding since midline laparotomy in emergency groin hernia repair can reach up to 53.1% [17] and it has been identified as a prognostic factor for postoperative morbidity [18]. However, our data seems rather to suggest that the need for an additional midline laparotomy and the decision to perform a non-mesh repair were not influenced by the initial approach as open preperitoneal or anterior.

The open preperitoneal method also was associated with significantly lower rates of recurrence, both by type of approach and by techniques. Recurrence rates after emergency groin hernia repair range from 0.9% to 10% [3,4,8,19,20]. In our study it was 8.5% (n = 27) and in the majority of cases was after a mesh plug repair (n = 17). In light of these results and following current clinical guidelines, the mesh plug repair should be avoided [1]. On the other hand, multivariate analysis indicated that female gender was the only risk factor for recurrence after emergency groin hernia repair, which is consistent with previous data [21]. A hypothesis for the higher recurrence rate in females could be that femoral hernias were missed at the primary procedure [22]. These findings make the open preperitoneal technique very attractive in the emergency setting, since it allows a complete exposure of the myopectineal orifice, being able to identify all possible hernias in the inguinofemoral region. The open preperitoneal mesh repair technique used in this study consists of creating a gap in the mesh for the passage of the inguinal cord elements. However, it is still unknown whether making a gap in the mesh would lead to a higher rate of recurrence or chronic pain.

The incidence of chronic postoperative inguinal pain in the present study was 2.2% without significant differences according to the type of approach and repair technique, while rates of 0.7%–75% have been reported in open hernia mesh repairs depending on the definitions of chronic postoperative inguinal pain and assessments methods [23]. In the context of emergency repairs, a rate of 5% has been reported [20]. A possible explanation for this relatively low incidence of chronic pain may be the high number of elderly patients and that the frequency of chronic postoperative inguinal pain decreases with age [24].

Different open surgical techniques have been described where the purpose is to place the mesh into the preperitoneal space [25]. However, a limited number of studies have reported the results of using the open preperitoneal approach in emergency groin hernia repair. Pans et al published one of the first studies describing 35 patients treated by insertion of a prosthetic mesh via midline preperitoneal approach. They concluded that the preperitoneal prosthesis implantation is safe, even when necrotic intestine or omentum was resected [7]. Karatepe et al reported the only randomized study comparing open posterior vs. open anterior approach with mesh, found no significant differences except for a lower incidence of second incisions in the posterior approach [6]. In a recent retrospective study, the authors included 146 patients and reported a total of 15 patients (10.3%) who developed complications, no mesh were removed, and 2 patients had recurrence with a median follow-up of 26 months [8]. Regarding the use of laparoscopic approach in emergency groin hernia repair, some authors have reported good results in selected patients, especially with TAPP approach [5]. However, some drawbacks have been described that have prevented a more widespread use of this approach in this context. Among the difficulties for the implementation of laparoscopy is the bowel distention that is frequently observed in these patients and can lead to conversion to open surgery and visceral injuries derived from laparoscopic manipulation [26]. Unlike the laparoscopic posterior approach, the open posterior approach is not limited to selected patients. With the open posterior approach, the possibility of visceral injury from manipulation is reduced and the presence of bowel distention is not an inconvenience for its performance. Therefore, our experience confirms that open preperitoneal repair using a posterior approach is effective and safe in the difficult setting of incarcerated/strangulated groin hernia.

In our study the morbidity rate was 48.1%, with 14.8% of major complications and a mortality of 8.5%, these numbers are substantially higher than those reported in other similar studies [2,4,8,17,18,19]. The explanation for these findings may be influenced by the fact that in our series a significant number of patients were elderly with high comorbidity. This is reflected in the fact that 60% of the patients were older than 75 years, with a high comorbidity represented by the fact that 43.4% were ASA II/IV. On the other hand, 28% of the patients underwent intestinal resection. These factors have been significantly associated with morbidity and mortality after emergency repair of abdominal wall hernias [27]. In line with the foregoing, in our multivariate analysis, patients older than 75 years and preoperative bowel obstruction were independent risk factors for postoperative morbidity, as described in previous studies [28]. On the other hand, CCI® was the only independent risk factor for mortality at 90 days in our series. It has recently been shown that CCI® can be a more accurate scale for measuring morbidity in high-risk patients with the probability of multiple complications [29]. To our knowledge, this is the first emergency groin hernia repair study to report postoperative morbidity using this risk scale. According to these findings, elderly patients with associated comorbidities, and especially women, could benefit from elective inguinal hernia repair to avoid the risks of emergency intervention for inguinal hernia, as reported in previous studies [4,30].

This study has several limitations: 1. observational study of a single center experience; 2. inconsistency in follow-up schedule in terms of limited number of patients followed up; 3. despite exhaustive efforts, not all the patients could be contacted by telephone for follow-up, so the reported recurrence and postoperative chronic inguinal pain rates could potentially underestimate the current rate. All would lead to inevitable bias and potentially underestimating hernia recurrence and long-term complication rates. Despite these limitations, our study provides new evidence on the clinical comparison of surgical approach in emergency groin hernia repair with a high number of patients.

In conclusion, this study has shown that the open preperitoneal approach was associated with lower rates of recurrence and associated midline laparotomy. Open preperitoneal access may be a good choice in the of context intestinal resection to avoid the morbidities associated with additional midline laparotomies. Mesh plug had a higher recurrence rate. The rest of anterior approaches were safe and effective in emergency groin hernia repair, and this can justify the choice of approach at the surgeon´s discretion.

Statements

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusion of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

Ethical review and approval was not required for the study on human participants in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The patients/participants provided their written consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

VR-G made substantial contributions to the conception and design of the study, acquisition of data, analysis, interpretation of data and drafting the article. MV, MM, RB, and AB-S made substantial contributions to the acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation of data. JP-R made substantial contributions drafting the article and revising it critically for important intellectual content. ML-C made substantial contributions drafting the article and revising it critically for important intellectual content and for the final approval of the version to be submitted.

Conflict of interest

ML-C has received honoraria for consultancy, lectures, support for travels and participation in review activities from BD-Bard, Medtronic and Gore. ML-C is the Editor-in-Chief of JAWS and declares that he did not participate in the management of the editorial process of the manuscript.

The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1.

HerniaSurge Group. International Guidelines for Groin Hernia Management. Hernia (2018) 22:1–165. 10.1007/s10029-017-1668-x

2.

Venara A Hubner M Le Naoures P Hamel JF Hamy A Demartines N . Surgery for Incarcerated Hernia: Short-Term Outcome with or without Mesh. Langenbecks Arch Surg (2014) 399:571–7. 10.1007/s00423-014-1202-x

3.

Bessa SS Abdel-fattah MR Al-Sayes IA Korayem IT . Results of Prosthetic Mesh Repair in the Emergency Management of the Acutely Incarcerated And/or Strangulated Groin Hernias: a 10-year Study. Hernia (2015) 19:909–14. 10.1007/s10029-015-1360-y

4.

Tastaldi L Krpata DM Prabhu AS Petro CC Ilie R Haskins IN et al Emergent Groin Hernia Repair: A Single center 10-year Experience. Surgery (2019) 165:398–405. 10.1016/j.surg.2018.08.001

5.

Chihara N Suzuki H Sukegawa M Nakata R Nomura T Yoshida H . Is the Laparoscopic Approach Feasible for Reduction and Herniorrhaphy in Cases of Acutely Incarcerated/Strangulated Groin and Obturator Hernia?: 17-Year Experience from Open to Laparoscopic Approach. J Laparoendoscopic Adv Surg Tech (2019) 29:631–7. 10.1089/lap.2018.0506

6.

Karatepe O Adas G Battal M Gulcicek OB Polat Y Altiok M et al The Comparison of Preperitoneal and Lichtenstein Repair for Incarcerated Groin Hernias: a Randomised Controlled Trial. Int J Surg (2008) 6:189–92. 10.1016/j.ijsu.2008.02.007

7.

Pans A Desaive C Jacquet N . Use of a Preperitoneal Prosthesis for Strangulated Groin Hernia. Br J Surg (1997) 84:310–2. 10.1046/j.1365-2168.1997.02509.x

8.

Liu J Chen J Shen Y . The Results of Open Preperitoneal Prosthetic Mesh Repair for Acutely Incarcerated or Strangulated Inguinal Hernia: a Retrospective Study of 146 Cases. Surg Endosc (2020) 34:47–52. 10.1007/s00464-019-06729-7

9.

Charlson ME Pompei P Ales KL MacKenzie CR . A New Method of Classifying Prognostic Comorbidity in Longitudinal Studies: Development and Validation. J Chronic Dis (1987) 40:373–83. 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8

10.

Read RC . The Preperitoneal Approach to the Groin and the Inferior Epigastric Vessels. Hernia (2005) 9:79–83. 10.1007/s10029-004-0240-7

11.

Mangram AJ Horan TC Pearson ML Silver LC Jarvis WR . Guideline for Prevention of Surgical Site Infection, 1999. Hospital Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol (1999) 20:247–80. 10.1086/501620

12.

Dindo D Demartines N Clavien P-A . Classification of Surgical Complications. Ann Surg (2004) 240:205–13. 10.1097/01.sla.0000133083.54934.ae

13.

Slankamenac K Graf R Barkun J Puhan MA Clavien P-A . The Comprehensive Complication Index. Ann Surg (2013) 258:1–7. 10.1097/SLA.0b013e318296c732

14.

Tastaldi L Barros PHF Krpata DM Prabhu AS Rosenblatt S Petro CC et al Hernia Recurrence Inventory: Inguinal Hernia Recurrence Can Be Accurately Assessed Using Patient-Reported Outcomes. Hernia (2020) 24:127–35. 10.1007/s10029-019-02000-z

15.

Baucom RB Ousley J Feurer ID Beveridge GB Pierce RA Holzman MD et al Patient Reported Outcomes after Incisional Hernia Repair-Establishing the Ventral Hernia Recurrence Inventory. Am J Sur (2016) 212:81–8. 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2015.06.007

16.

Hu QL Chen DC . Approach to the Patient with Chronic Groin Pain. Surg Clin North Am (2018) 98:651–65. 10.1016/j.suc.2018.02.002

17.

Kjaergaard J Bay-Nielsen M Kehlet H . Mortality Following Emergency Groin Hernia Surgery in Denmark. Hernia (2010) 14:351–5. 10.1007/s10029-010-0657-0

18.

Romain B Chemaly R Meyer N Brigand C Steinmetz JP Rohr S . Prognostic Factors of Postoperative Morbidity and Mortality in Strangulated Groin Hernia. Hernia (2012) 16:405–10. 10.1007/s10029-012-0937-y

19.

Dai W Chen Z Zuo J Tan J Tan M Yuan Y . Risk Factors of Postoperative Complications after Emergency Repair of Incarcerated Groin Hernia for Adult Patients: a Retrospective Cohort Study. Hernia (2019) 23:267–76. 10.1007/s10029-018-1854-5

20.

Lohsiriwat D Lohsiriwat V . Long-term Outcomes of Emergency Lichtenstein Hernioplasty for Incarcerated Inguinal Hernia. Surg Today (2013) 43:990–4. 10.1007/s00595-013-0489-5

21.

Burcharth J Pommergaard H-C Bisgaard T Rosenberg J . Patient-Related Risk Factors for Recurrence after Inguinal Hernia Repair. Surg Innov (2015) 22:303–17. 10.1177/1553350614552731

22.

Bay-Nielsen M Kehlet H . Inguinal Herniorrhaphy in Women. Hernia (2006) 10:30–3. 10.1007/s10029-005-0029-3

23.

Aasvang E Kehlet H . Chronic Postoperative Pain: the Case of Inguinal Herniorrhaphy. Br J Anaesth (2005) 95:69–76. 10.1093/bja/aei019

24.

Reinpold W . Risk Factors of Chronic Pain after Inguinal Hernia Repair: a Systematic Review. Innov Surg Sci (2017) 2:61–8. 10.1515/iss-2017-0017

25.

Andresen K Rosenberg J . Open Preperitoneal Groin Hernia Repair with Mesh: A Qualitative Systematic Review. Am J Surg (2017) 213:1153–9. 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2017.01.014

26.

Rebuffat C Galli A Scalambra MS Balsamo F . Laparoscopic Repair of Strangulated Hernias. Surg Endosc (2006) 20:131–4. 10.1007/s00464-005-0171-0

27.

Martínez-Serrano MÁ Pereira JA Pereira JA Sancho JJ López-Cano M Bombuy E et al Study Group of Abdominal Hernia Surgery of the Catalan Society of SurgeryRisk of Death after Emergency Repair of Abdominal wall Hernias. Still Waiting for Improvement. Langenbecks Arch Surg (2010) 395:551–6. 10.1007/s00423-009-0515-7

28.

Chamary VL . Femoral Hernia: Intestinal Obstruction Is an Unrecognized Source of Morbidity and Mortality. Br J Surg (2005) 80:230–2. 10.1002/bjs.1800800237

29.

Veličković J Feng C Palibrk I Veličković D Jovanović B Bumbaširević V . The Assessment of Complications after Major Abdominal Surgery: A Comparison of Two Scales. J Surg Res (2020) 247:397–405. 10.1016/j.jss.2019.10.003

30.

López-Cano M Rodrigues-Gonçalves V Verdaguer-Tremolosa M Petrola-Chacón C Rosselló-Jiménez D Saludes-Serra J et al Prioritization Criteria of Patients on Scheduled Waiting Lists for Abdominal wall Hernia Surgery: a Cross-Sectional Study. Hernia (2021) 25:1659–66. 10.1007/s10029-021-02378-9

Summary

Keywords

open preperitoneal hernia repair, incarcerated, strangulated, prosthetic mesh repair, emergent groin hernia

Citation

Rodrigues-Gonçalves V, Verdaguer M, Moratal M, Blanco R, Bravo-Salva A, Pereira-Rodíguez JA and López-Cano M (2022) Open Emergent Groin Hernia Repair: Anterior or Posterior Approach?. J. Abdom. Wall Surg. 1:10586. doi: 10.3389/jaws.2022.10586

Received

19 April 2022

Accepted

23 June 2022

Published

21 July 2022

Volume

1 - 2022

Updates

Copyright

© 2022 Rodrigues-Gonçalves, Verdaguer, Moratal, Blanco, Bravo-Salva, Pereira-Rodíguez and López-Cano.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: V. Rodrigues-Gonçalves, vrodrigues@vhebron.net, orcid.org/0000-0001-8998-2327

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.