Abstract

Data on the problems physicians face when providing care for atopic dermatitis (AD) is limited. To understand the current status of AD management in Japan and identify the difficulties physicians are having and their support requirements, a cross-sectional online survey was conducted using the AD task force of the Japanese Society for Cutaneous Immunology and Allergy. Society members were sent an online questionnaire on demographic information, daily clinical practice, and perceptions of AD management. Using responses to 17 items listed as barriers to the treatment of atopic dermatitis (Question 12) and questions about the treatment difficulty of those items, 284 respondents were divided into three groups using unstratified cluster analysis. These three groups were classified as high-difficulty, medium-difficulty, and low-difficulty groups, and the relationship between physicians’ cognition and daily practice was examined for each group. There were no significant differences in affiliations or specializations among the three clusters. The low-difficulty group had a significantly higher proportion of participants believing that it was possible to achieve long-term remission, satisfaction, and motivation in AD management while carrying out precise assessments of skin lesions as part of their daily practice. Some physicians experience problems in their practice. This results indicate that AD management can be improved if satisfaction and motivation can be increased by providing appropriate support.

Introduction

Atopic dermatitis (AD) is a common skin disease seen in 9.98% of all dermatology outpatients [1]. The history of AD treatment in Japan during the 1990 s was very problematic, causing serious distress for both patients and physicians. Distrust of the approach used in regular medicine originated with concerns about the use of topical corticosteroids and was exacerbated by mass media misinformation (steroid bashing). This has led to confusion regarding the management of AD, resulting in an increasing number of patients with severe AD, which adversely affects their quality of life and social activities [2–4].

To address this situation, the first AD clinical practice guidelines were developed by the Japanese Dermatological Association in 2000 and have subsequently been revised to improve treatment outcomes and respond to advances in understanding the pathophysiology and treatment options [5, 6]. This has led to the popularization of standard treatments and improved therapies for AD over the past two decades. However, there are still many cases in which long-term control is not achieved due to a lack of appropriate treatment. In such cases, dermatologists should be responsible for providing more specialized management, considering individual characteristics, and going beyond guidelines. Variations in treatment outcomes may depend on differences in the skills, abilities, or attitudes of dermatologists.

Expensive novel therapeutic agents have recently been developed for severe AD, including molecularly targeted drugs [7–9]. Appropriate selection of patients for these new drugs is necessary to improve both patients’ quality of life and the sustainability of healthcare finances. Therefore, dermatologists must maximize the effectiveness of conventional drugs by improving and standardizing AD management attitudes and skills.

The Task Force on Atopic Dermatitis of the Japanese Society for Cutaneous Immunology and Allergy (JSCIA) is currently preparing continuing professional education for dermatologists to improve the management of atopic dermatitis. We conducted a questionnaire survey to understand the current clinical practices related to AD, how it is being treated, and what information or support is required by dermatologists. This study also aimed to identify barriers to AD treatment that could be addressed by providing information to healthcare professionals and patients. The questionnaire items were chosen based on the hypothesis that the issues and problems in AD management perceived by physicians in daily clinical practice may influence their perspective on the disease and treatment plan. No previous studies have examined physicians’ perspectives on AD management, including their motivation or perceived difficulty in treating this condition.

Materials and methods

Development of a questionnaire to investigate AD practice among healthcare professionals

We prepared a draft questionnaire to investigate physicians’ performance, difficulties, and treatment strategies for managing AD. Questionnaire items were prepared based on the knowledge of JSCIA task force members. A first draft questionnaire was prepared with 42 questions related to demographic information, practices related to patients with AD in the outpatient setting, implementation of proactive treatment, implementation of patient education, and perceptions of AD practice. This was piloted with five dermatologists to verify the accuracy of the text, the validity of the questions, and the time required to answer the questionnaire. The questionnaire was revised following feedback to obtain the final version (Table 1).

TABLE 1

| No | Sub No | Question | How to answer |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Consent to participate in the following questionnaire | Yes or No If No, Exit | |

| 2 | 1 | “Please respond with respect to yourself.” Age | years |

| 2 | Years of clinical experience in dermatology | years | |

| 3 | Please indicate the prefecture where you mainly work | prefectures | |

| 4 | Your sex | Choose Male or Female | |

| 5 | Please indicate the type of facility in which you are employed | Please select one from the list below | |

| ○ University hospital | |||

| ○ General hospital other than university hospital | |||

| ○ Private clinic | |||

| ○ Other | |||

| 6 | Please choose the qualification(s) in which you are accredited | Multiple answers allowed | |

| ○ Board certified dermatologist | |||

| ○ Board certified allergist | |||

| ○ Board certified allergy instructor | |||

| ○ Not a specialist | |||

| 7 | −1 | How familiar are you with the “Clinical Guidelines for Atopic Dermatitis (AD) 2018” published in the “Journal of Japanese Dermatology, 2018:128;2431–2502” | Choose from grade 0: not at all to 10: all |

| −2 | How much do you refer to these guidelines in your practice? | Same as Q7 -1 | |

| 8 | “Please respond regarding the general situation in your outpatient consultation. If you have outside duties, please include these.” | ||

| 1 | Number of consultation days per week | Number | |

| 2 | Number of patients per month | Number | |

| 3 | Number of adult patients with atopic dermatitis per month | Number | |

| 4 | Number of pediatric patients under 15 years of age with AD per month | Number | |

| 5 | Number of infant patients (under 1 year old) with AD per month | Number | |

| 6 | Number of patients treated with dupilumab | Number | |

| 7 | Number of patients treated with cyclosporine | Number | |

| 8 | Consultation time for a first visit with an adult patient with AD (minutes) | Number | |

| 9 | Consultation time for a return visit with an adult patient with AD (minutes) | Number | |

| 10 | Consultation time for a first visit with a patient under the age of 15 years with AD (minutes) | Number | |

| 11 | Consultation time for a return visit with a patient under the age of 15 years with AD (minutes) | Number | |

| 9 | This question is regarding the severity of AD in your first-visit patients. Please give a percentage of each severity such that the total is 100% | Mild (a %), Moderate (b %), Severe (c %), Most severe (d %) a + b + c + d = 100% | |

| 10 | How rewarding for you is consultation for AD? (five-level evaluation) | Very rewarding, Somewhat rewarding, Neither, Not very rewarding, Not rewarding at all | |

| 11 | Please indicate your satisfaction with and motivation for treating AD, on a scale of 0–10 | Scale number | |

| 12 | “Please indicate your difficulties with clinical practice for AD” | five-level evaluation: Very difficult, Difficult, Neither, Not so difficult, Not difficult at all | |

| 1 | Too many complaints from patients | ||

| 2 | Patients’ low motivation for treatment | ||

| 3 | Patients’ symptoms that do not improve | ||

| 4 | Repeated exacerbations and remissions of patients’ symptoms over a long time | ||

| 5 | Too many patients | ||

| 6 | Long consultation time for one patient | ||

| 7 | Low medical fee (Dermatology Guidance and Management Fees for Specified Diseases [II]) | ||

| 8 | Searching for aggravating factors | ||

| 9 | Difficulty in assessing the severity of skin symptoms | ||

| 10 | Psychological management | ||

| 11 | Management of daily life | ||

| 12 | Instruction based on a staged treatment plan, such as the induction period and remission maintenance period | ||

| 13 | Setting treatment goals tailored to individual patients | ||

| 14 | Sharing treatment goals with patients | ||

| 15 | Describing topical steroid therapy | ||

| 16 | Understanding patients’ thoughts on topical steroids | ||

| 17 | Determining patients’ adherence to treatment | ||

| 13 | “The following questions address the examination of patients with AD at the first visit.” | five-level evaluation: always, often, sometimes, rarely, not at all | |

| 1 | Do you explain treatment plans and goals? | ||

| 2 | Do you explain treatment plans and goals? | ||

| 3 | Do you record the distribution of skin rashes (e.g., sketches, photos)? | ||

| 4 | Do you assess the severity of the patient? | ||

| 14 | In your daily practice, how do you assess the severity of the patient at the first visit? | Multiple answers allowed | |

| ○ Evaluation by impression during the examination | |||

| ○ Degree of itching in the patient | |||

| ○ Visual inspection of the exposed skin (with clothes on) | |||

| ○ Visual inspection of whole skin (clothes off) | |||

| ○ Palpation of skin lesions | |||

| ○ Measurement of serum Thymus and Activation-Regulated Chemokine (TARC) level | |||

| ○ Blood tests other than TARC | |||

| ○ Not evaluated | |||

| ○ Other | |||

| 15 | When adult patients with AD need topical steroid application to their whole body, how many grams of topical steroids per week do you normally prescribe? | Grams | |

| 16 | Do you make a revisit plan (such as scheduling the next appointment) for a patient who requires continued treatment? | five-level evaluation: always, often, sometimes, rarely, not at all | |

| 17 | How do you evaluate the effect of treatment at the return visit? | Multiple answers allowed | |

| ○ Evaluation by impression during the examination | |||

| ○ Degree of itching in the patient | |||

| ○ Visual inspection of the exposed skin (with clothes on) | |||

| ○ Visual inspection of whole skin (with clothes off) | |||

| ○ Palpation of skin lesions | |||

| ○ Measurement of serum TARC level | |||

| ○ Blood tests other than TARC | |||

| ○ Review of charts, photos, and descriptions in the medical records | |||

| 18 | What kind of treatment do you use for moderate to severe refractory patients? | Multiple answers allowed | |

| ○ Referral to a core hospital | |||

| ○ Strengthening topical therapy, considering induction of remission | |||

| ○ Continue the treatment as before | |||

| ○ Systemic administration of steroids | |||

| ○ Systemic administration of cyclosporine | |||

| ○ Systemic administration of dupilumab | |||

| 19 | Regarding cooperation with local clinics and hospitals, is there a collaborative core hospital in your area that can provide remission induction and patient education? | 1 choice, Yes or No | |

| 20 | Do you usually provide proactive therapy with topical anti-inflammatory drugs to achieve the treatment goal for AD? | 1 choice, Yes or No (please proceed to [Q32]) | |

| 21 | What criteria do you usually use to select patients for proactive therapy? | Multiple answers allowed | |

| ○ Patient’s age | |||

| ○ Site of eczema | |||

| ○ Patients with high severity (Please respond to Q22) | |||

| ○ Patients with repeatedly relapsed eruptions | |||

| ○ Patients with good treatment adherence | |||

| ○ Patients who can visit the hospital regularly | |||

| ○ Patients with serum TARC measurements | |||

| ○ Patients who have difficulty maintaining remission | |||

| ○ Other | |||

| 22 | If you responded, “Patients with high severity” in Q21 what level of severity are patients in whom you use proactive therapy? | 1 choice: Mild, Moderate, Severe, Most severe | |

| Please respond based on the severity at the first visit | |||

| 23 | What topical drug(s) do you use for proactive therapy? | Multiple answers allowed | |

| ○ Topical steroids | |||

| ○ Topical tacrolimus | |||

| ○ Other | |||

| 24 | Do you have any criteria for ending proactive therapy? | 1 choice | |

| ○ Yes, I have such criteria. (Please complete Q25) | |||

| ○ No, I don’t have any such criteria | |||

| 25 | If you responded, “Yes, I have such criteria,” in Q24, what are your criteria for ending proactive therapy? | Multiple answers allowed | |

| If you choose “The period of proactive therapy” below, please state the period duration | |||

| ○ The period of proactive therapy | |||

| ○ Patient’s age | |||

| ○ Site of eczema | |||

| ○ History of eczema relapse | |||

| ○ Feasibility and acceptability of patients’ family regarding proactive therapy | |||

| ○ Patient has smooth skin without any inflammation | |||

| ○ Other | |||

| 26 | How long do you continue proactive therapy? | number of months | |

| 27 | At what stage do you switch to proactive therapy? | Multiple answers allowed | |

| ○ When itching has improved to some extent | |||

| ○ When skin redness is gone | |||

| ○ When the skin becomes smooth visually and to the touch | |||

| ○ One month after induction of remission with topical steroids | |||

| ○ On a case-by-case basis | |||

| ○ When the serum TARC level has decreased | |||

| ○ Other | |||

| 28 | What proportion of patients with frequent relapsing do you switch to proactive therapy? | Same as Q7 -1 | |

| 29 | At what itch score (0–10) do you switch the patient to proactive therapy | 0 to 10 | |

| 30 | What is the specific serum TARC level when you switch the patient to proactive therapy? | pg/mL | |

| 31 | What proportion of your patients have achieved the treatment goal for AD with proactive therapy? | Same as Q7 -1 | |

| 32 | Is it possible to follow up patients who are well-controlled with proactive therapy after educational intervention in a core hospital? | 1 choice | |

| ○ Yes, I can follow up | |||

| ○ Yes, I can follow up if I know how to do so | |||

| ○ It’s difficult to follow up these patients (Please respond to Q33) | |||

| 33 | If you responded " It’s difficult to follow up” in Q32, what makes following up difficult? | Multiple answers allowed | |

| ○ I don’t know the patients’ clinical course and severity before treatment | |||

| ○ I don’t have enough time to explain proactive therapy to patients | |||

| ○ I don’t know how long patients should continue proactive therapy | |||

| ○ I do not agree with the concept of proactive therapy | |||

| ○ Other | |||

| 34 | What are the hurdles in providing proactive therapy? | Multiple answers allowed | |

| Please respond in terms of its applicability | |||

| ○ Explaining the therapy to patients | |||

| ○ Anxiety about whether the external dose can be reduced after the initial large external use | |||

| ○ I don’t know the regions of application | |||

| ○ I don’t know the endpoint | |||

| ○ I don’t have any experience of success | |||

| ○ I don't know whether the skin condition of patients who have stopped visiting a doctor is improving | |||

| ○ Other | |||

| 35 | Do you have any documents or staff to assist you when you are asked to explain AD treatment in detail or important points regarding daily life? | Multiple answers allowed | |

| ○ Nurse | |||

| ○ Pharmacist | |||

| ○ Brochure | |||

| ○ Internet | |||

| ○ Medical partners (other than nurses and pharmacists) | |||

| ○ None | |||

| ○ Other | |||

| 36 | The American Dermatological Association has created video educational materials on how to apply topical agents and how to give specific instructions regarding activities of daily living (bathing and so on). These materials are posted on YouTube and other platforms to help educate patients and provide lifelong education for physicians. Would you watch (and recommend to patients) video educational materials containing practical information if available in Japan? | Multiple answers allowed, three-level evaluation: I’d love to use it, May be used, No need | |

| ○ Yes (for physicians) | |||

| ○ Yes (for patients) | |||

| 37 | What do you think is necessary in video education materials regarding treatment practice? | Multiple answers allowed | |

| ○ How to use topical steroids and tacrolimus | |||

| ○ Proactive therapy | |||

| ○ How to use topical moisturizers | |||

| ○ Bathing and washing habits | |||

| ○ Control of sweating | |||

| ○ How to deal with atopic itch | |||

| ○ Pathophysiology of atopic dermatitis | |||

| ○ Explanation of standard treatment based on guidelines | |||

| ○ Other | |||

| 38 | Would you like to use DVDs or Internet delivery as a medium for video education materials? | Multiple answers allowed | |

| ○ DVD | |||

| ○ Internet delivery | |||

| ○ Both DVD and Internet | |||

| 39 | Who would you like to recommend viewing such video education materials? | Multiple answers allowed | |

| ○ Patients | |||

| ○ Patients’ family | |||

| ○ Physicians | |||

| ○ Nurses | |||

| ○ Pharmacists | |||

| ○ Medical partners (except nurses and pharmacists) | |||

| 40 | Do you think it is possible to achieve good long-term control of AD? | Same as Q7 -1 | |

| 41 | The following questions address the burden of AD. | ||

| 1 | Do you ask the patient about the effects of AD on their mental health (e.g., feeling depressed or anxious)? | four-level evaluation: be doing, mostly doing, not doing much, not doing | |

| 2 | Do you instruct patients in how to reduce the burden of external treatment in daily medical care? | ||

| 3 | Do you ask or confirm with the patient about daily life restrictions (loss of concentration at work or school, inability to wear desired clothing) because of AD? | ||

| 42 | Do you have any comments or requests regarding this survey? | free-text description |

Web-based questionnaire items.

Survey on AD, clinical practice 2019 in Japan.

Online survey of dermatologists in Japan

From October 2019 to January 2020, a web-based survey questionnaire was administered to 1,259 dermatologists affiliated with the JSCIA using the Questant system from MACROMILL, Inc. (Tokyo, Japan). This study was reviewed and approved by the Ethics Approval Committee of the JSCIA (approval date: 31 July 2019). The survey questions were presented after each respondent had read the purpose of the study and provided consent to use their data.

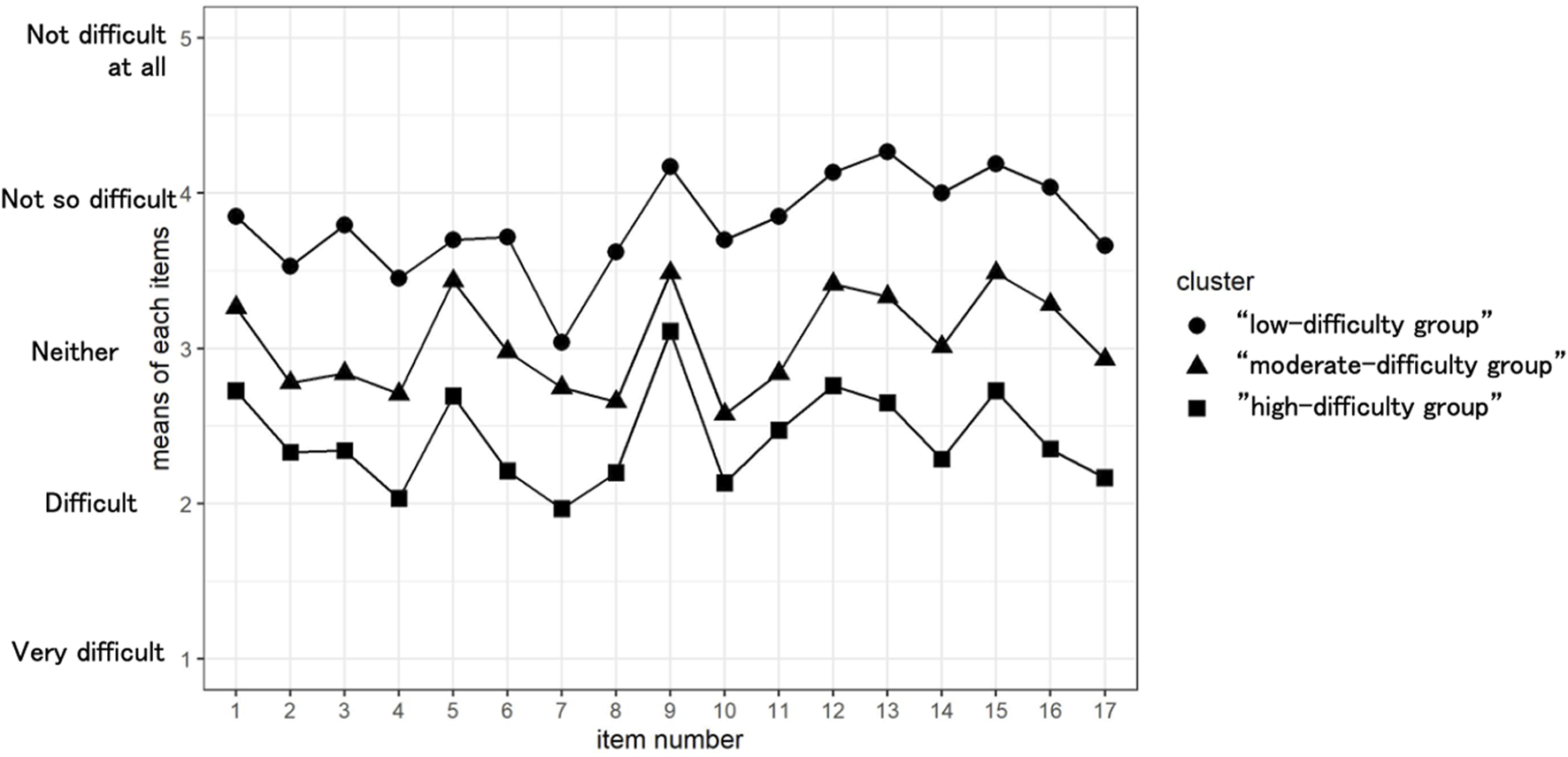

Cluster analysis

Respondents were grouped by non-stratified cluster analysis using a question on their perception of the difficulty of treating AD (Question [Q] 12) to examine the relationship between each physician’s perception of AD as a condition, treatment strategy, and their usual practice. The appropriate number of clusters was set to three, and the physicians were grouped into three clusters: high, moderate, and low difficulty. Cluster analyses were performed using the NbClust packages and k-means methods.

Statistical analysis

R 4.0.3 (The R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria) was used for statistical analysis. Cronbach’s alpha was used to examine the internal validity. The following variables were compared among the clusters: attributes (age and whether the respondent was an authorized dermatologist or allergist), the degree to which the physician had read or referred to the atopic dermatitis guidelines, and actual performance in outpatient clinics, including proactive therapy. Multiple comparisons were performed using the Kruskal–Wallis and Steel–Dwass tests for continuous variables and the chi-square test and residual analysis for nominal variables.

Results

Participants

We received 284 responses (response rate: 22.5%) from 1,259 JSCIA members whose e-mail addresses were registered on the list of JSCIA members. After excluding incorrect information, 243 responses (an effective response rate of 85.6%) were considered valid. The alpha coefficient of the questionnaire was 0.78, confirming its internal validity.

Outpatient clinic performance

The median age of the responding physicians was 50 years (interquartile range [IQR] 42–59 years), the median level of dermatology experience was 22 years (IQR 14.5–31.5 years), 137 (56.4%) were men and 106 (43.6%) were women. The place of work (Q5), authorized specialisms (Q6), and outpatient medical care performance (Q8) are summarized in Table 2. The question regarding the degree to which the physician read the AD clinical practice guidelines [6] (Q7) was based on an 11-point scale. Physicians who scored five or more points were considered highly aware. The percentage of physicians with high awareness was 86.4% for “have read” and 87.6% for ‘have been referred to. Therefore, respondents often read and used these guidelines as references.

TABLE 2

| Participants’ characteristics | n (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Work at | University hospital | 106 (43.6%) | |||

| National/public general hospital other than university hospital | 64 (26.3%) | ||||

| Private clinic | 73 (30.0%) | ||||

| Specialist (Multiple answers allowed) | Dermatologist | 216 (88.9%) | |||

| Allergist | 72 (29.6%) | ||||

| Other | 17 (7.0%) | ||||

| Not a specialist | 4 (9.9%) | ||||

| Outpatient medical records in this survey | Median | IQR25 | IQR75 | ||

| Number of consultation days per week (days) | 5 | 4 | 5 | ||

| Number of adult patients with AD per month | 50 | 20 | 100 | ||

| Number of children (under 15 years of age) with AD per month | 10 | 5 | 30 | ||

| Number of infants (0 years old) with AD per month | 1 | 0 | 5 | ||

| Number of patients treated with dupilumab | 2 | 0 | 7 | ||

| Number of patients treated with cyclosporine | 5 | 2 | 20 | ||

| Initial consultation time for adult patients with AD (minutes) | 15 | 10 | 20 | ||

| Revisit consultation time for adult patients with AD (minutes) | 6 | 5 | 10 | ||

| Initial consultation time for child (under 15 years of age) patients with AD (minutes) | 15 | 10 | 20 | ||

| Revisit consultation time for child (under 15 years of age) patients with AD (minutes) | 5 | 5 | 10 | ||

| Patient severity at initial consultation | Mild (%) | 29 | 10 | 40 | |

| Moderate (%) | 30 | 25 | 45 | ||

| Severe (%) | 20 | 10 | 30 | ||

| Most severe (%) | 10 | 5 | 10 | ||

Participants’ characteristics (Question 5: Q5 and Q6) and outpatient practice (Q8) (n = 243).

Q, question; IQR, interquartile range.

Many physicians felt that AD consultations were rewarding (Q10: five-level evaluation), with 30% thinking they were very rewarding and 57.2% thinking they were somewhat rewarding. In assessing satisfaction with and motivation to provide AD care using a 10-point scale (Q11), 90.5% of the respondents scored at least five for satisfaction and 95.6% for motivation. In response to “Do you think it is possible to achieve good long-term AD control?” (Q40), 82% of respondents gave a score of ≥ 5, and 55.4% gave a score of ≥ 8 on an 11-point scale (0, not good long-term control; 10, good long-term control).

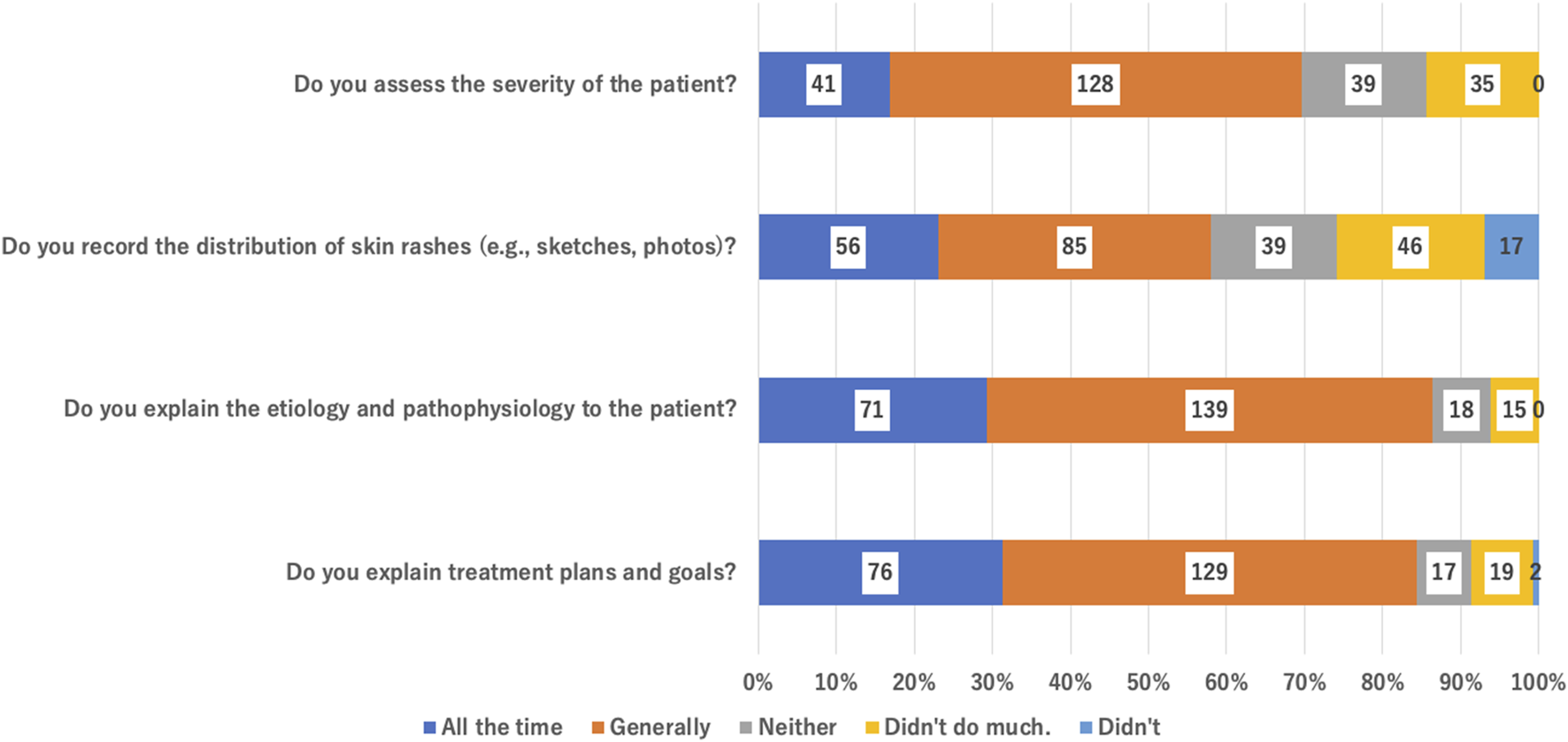

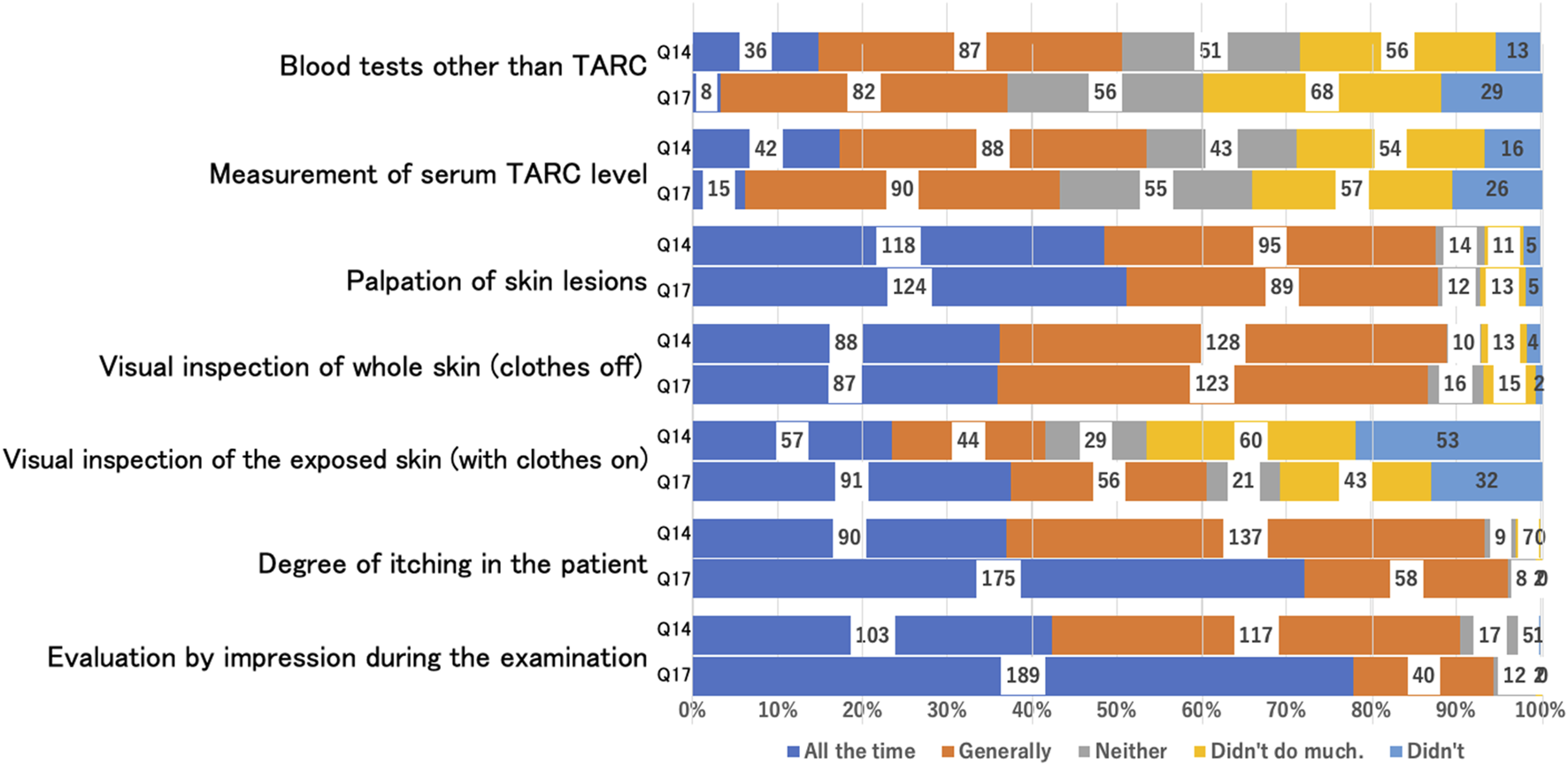

For the question about the required amount of topical corticosteroid for use on the entire adult body per week (Q15), the median was 50 g (IQR, 30–100 g). Figure 1 summarizes the physicians’ approach during the patient’s initial visit. More than 60% replied that they “always” or “usually” assessed severity, made a rash distribution record, and explained the etiology, current condition, and treatment goals at each patient’s first visit (Q13). Figure 2 summarizes the differences in the severity assessments between the initial and second visits. At the first visit, 90% “always” or “usually” assessed their patient’s severity by an entire body undressed inspection with palpation and discussion about the patient’s level of itching.

FIGURE 1

Physicians’ activity at a patient’s initial visit for AD (Q13).

FIGURE 2

Comparison of assessment of severity at initial visit (Q14) and revisit (Q17).

However, 25% always examined only the exposed skin lesions, and this ratio increased to 40% during revisits. Most physicians also assess severity by patient-reported degree of itching, and the number of respondents saying that they “generally” did this increased to 70% for revisits. Half (50%) of the patients were assessed for blood biomarkers, including serum Thymus and Activation-Regulated Chemokine (TARC), at the initial visit, falling to 40% on revisiting. Of the respondents, 95.1% said that they “always” or “often” gave directions for the next visit when the patient required ongoing treatment (Q16).

Proactive therapy

More than 90% of the physicians implemented proactive therapy; a fixed tendency was not observed in the standard for proactive therapy. A total of 97 physicians (43%) met the criteria for withdrawal from proactive therapy; these physicians were significantly older than physicians who did not meet the criteria for withdrawal (mean ± standard deviation: 51.0 ± 10.4 vs. 48.9 ± 10.4; p < 0.001 [Welch’s t-test]) and were significantly more likely to have an allergist (p = 0.04858; Pearson’s chi-squared test). The median time to discontinuation of proactive therapy after induction of remission was 6 months, but there was no consistent trend, nor was there a consistent trend in the criteria for the symptoms and tests that should be used to decide on discontinuation.

Educational tools

When asked about the tools they used to support their explanations of treatment details or how to manage daily activities, such as bathing (Q35: multiple answers possible), the most common were brochures (66.3%) and nurses’ education (44.9%). Overall, 42.8% thought that video education materials were necessary (Q36) “for physicians” and 59.3% “for patients,” and a range of content was sought. Over 80% wanted video materials for treatment practice (Q37: multiple answers allowed), 52.3% wanted these materials delivered over the internet (Q38), and 5.8% preferred a DVD. The proposed targets of the materials were patients, their families, physicians, nurses, pharmacists, and other medical partners. More than 50% wanted materials available to all these groups (Q39).

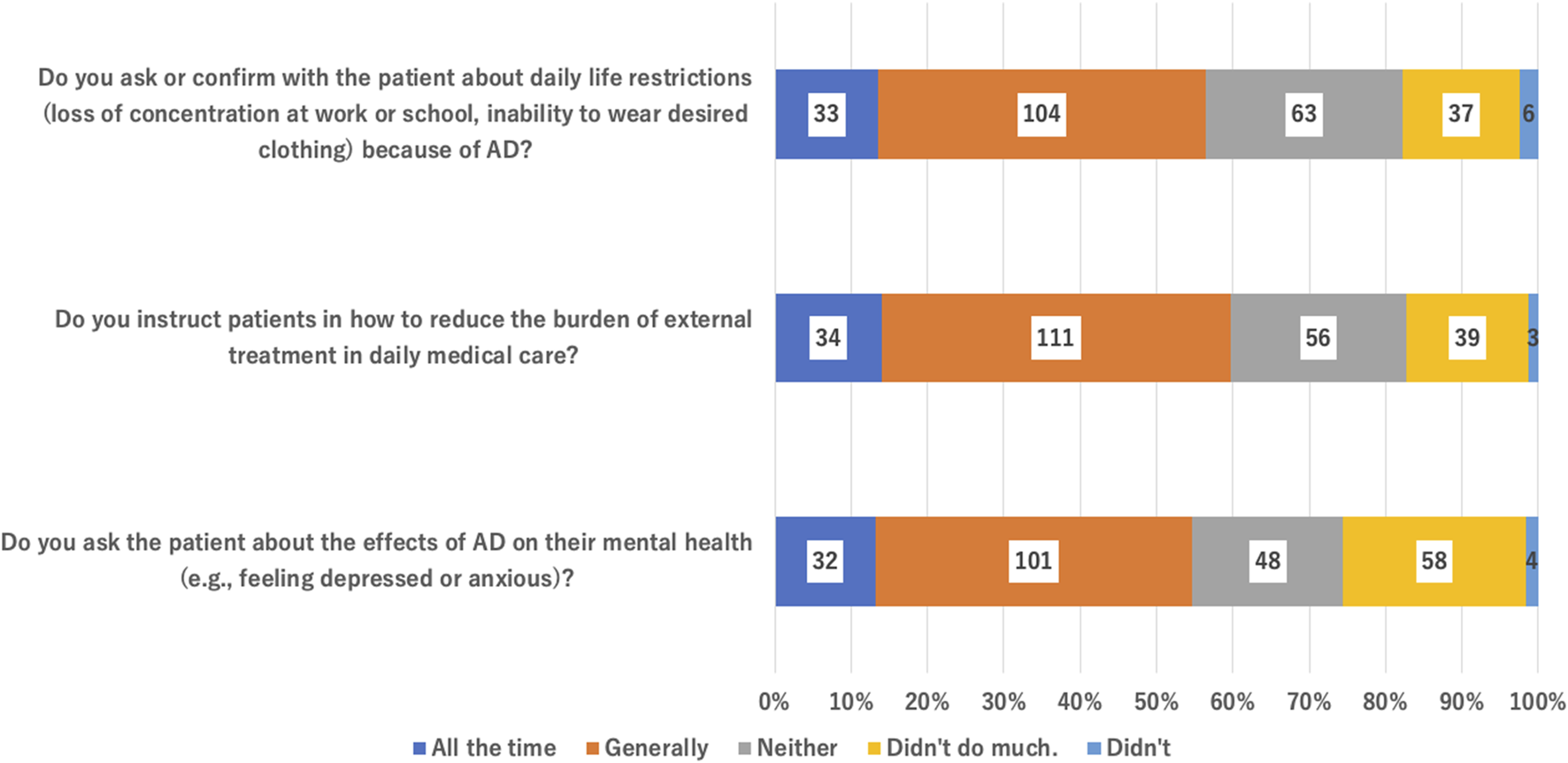

Assessment of AD disease burden

More than 50% of respondents “always” or “usually” asked AD patients about their burden of disease (Q41, Figure 3).

FIGURE 3

Questions asked to assess the burden of AD (Q41).

Cluster analysis according to the perception of treatment difficulty

Cluster analysis of the responses to the question on the difficulty of treating AD (Q12) provided three clusters. Cluster 1 (53 respondents) had a high overall score (low-difficulty group), Cluster 2 (99 respondents) had an intermediate score (moderate-difficulty group), and Cluster 3 (91 respondents) had a low overall score (high-difficulty group) (Figure 4). Significant differences were observed between the three clusters in the responses to several questions, particularly “Do you think it is possible to achieve good long-term control of AD?,” “Satisfied with AD treatment,” and “Motivation to provide AD treatment” (Q11). However, no significant differences were found in age (Q2), work style (Q5), specialty (Q6), number of outpatients (Q8), or the number of patients treated with cyclosporine or dupilumab (Q8) (Table 3). Cluster 1 also answered “yes” significantly more often than Cluster 3 (p = 0.026, Pearson’s chi-square test) to “Do you assess the severity of the patient during the first examination?” (Q13 and Q14). Similarly, for evaluation of the effectiveness of treatment at revisit (Q17), those in Cluster 1 were significantly more likely to say that they “rarely” or “not at all” used a visual inspection only of the exposed skin (with clothes on). Those in Cluster 3 were significantly less likely to say they did this “rarely” or “not at all” (p = 0.027, Pearson’s chi-square test). Significantly fewer respondents in Cluster 1 said they wanted training via video streaming (Q36), and significantly more selected “not required” (Table 3; p = 0.031, Pearson’s chi-squared test).

FIGURE 4

Comparison of physicians’ views about factors associated with AD, by cluster, based on the degree of difficulty expressed about treating AD in clinical practice (Q12).

TABLE 3

| Cluster | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1: Low- difficulty group (n = 53) | 2: Moderate- difficulty group (n = 99) | 3: High- difficulty group (n = 91) | p-value | |||

| Age (question 2–1: Q2-1) | Years; median (IQR) | 55 (45.0–60) | 57 (41.5–58) | 49 (41.0–58) | 0.075a | |

| Work style (Q5) | University hospital | Number (%) | 31 (29.2) | 41 (38.7) | 34 (32.1) | 0.059b |

| Community hospital | Number (%) | 12 (18.8) | 30 (46.9) | 22 (34.4) | ||

| Private clinic | Number (%) | 10 (13.7) | 28 (38.4) | 35 (47.9) | ||

| Dermatologist (Q6) | Yes | Number (%) | 50 (23.1) | 85 (39.4) | 81 (37.5) | 0.284b |

| No | Number (%) | 3 (11.1) | 14 (51.9) | 10 (37.0) | ||

| Allergist (Q6) | Yes | Number (%) | 19 (26.4) | 26 (36.1) | 27 (37.5) | 0.467b |

| No | Number (%) | 34 (19.9) | 73 (42.7) | 64 (37.4) | ||

| Guidelines for AD 2018 (Q7) | Do you read? | Scale; median (IQR) | 7 (5–10) | 8 (6–10) | 7 (5–9.5) | 0.140c |

| Do you refer to it? | Scale; median (IQR) | 7 (5–9) | 8 (6–9) | 8 (6–10) | 0.269c | |

| Outpatient treatment results | Do you think it is possible to achieve good long-term control of AD? (Q40) | Scale; median (IQR) | 8 (7–10) | 7 (5–9) | 8 (5–8) | 0.018c |

| Satisfaction with AD treatment (Q11-1) | Scale; median (IQR) | 8 (7–9) | 7 (6–8) | 6 (5–7) | 0.001c | |

| Motivation to provide AD treatment (Q11-2) | Scale; median (IQR) | 8 (7–10) | 8 (7–8) | 7 (6–8) | 0.019c | |

| Number of AD outpatients (Q8) | Number; median (IQR) | 50 (20–100) | 40 (20–100) | 50 (20–120) | 0.430c | |

| Patients treated with cyclosporine (Q8) | Number; median (IQR) | 5 (2–20) | 5 (2–20) | 5 (1–17.5) | 0.475c | |

| Patients treated with dupilumab (Q8) | Number; median (IQR) | 3 (1–12) | 2 (0–8) | 2 (0–5) | 0.176c | |

| One week’s steroid prescription (Q15) | Grams; median (IQR) | 70 (40–100) | 50 (30–100) | 50 (30–100) | 0.211c | |

| Proactive therapy (Q24) | With a criterion to discontinue | Number (%) | 26 (53.1) | 42 (48.3) | 29 (33.7) | 0.051a |

| Without a criterion to discontinue | Number (%) | 23 (46.9) | 45 (51.7) | 57 (66.3) | ||

| Assess severity at first visit (Q13-4) | Always or often | Number (%) | 44 (83) | 70 (70.7) | 55 (60.4) | 0.026b |

| Sometimes | Number (%) | 2 (3.8) | 18 (18.2) | 19 (20.9) | ||

| Rarely or not at all | Number (%) | 7 (13.2) | 11 (11.1) | 17 (18.7) | ||

| Visual inspection of the exposed skin (with clothes on) (Q17) | Always or often | Number (%) | 29 (54.7) | 57 (57.6) | 61 (66.7) | 0.027b |

| Sometimes | Number (%) | 1 (1.9) | 9 (9.1) | 11 (12.1) | ||

| Rarely or not at all | Number (%) | 23 (43.4) | 33 (33.3) | 19 (20.9) | ||

| Video-based education for physicians (Q36) | I’d love to use it | Number (%) | 16 (30.2) | 46 (46.5) | 42 (46.2) | 0.031b |

| Might use it | Number (%) | 25 (47.2) | 45 (45.5) | 42 (46.2) | ||

| Not required | Number (%) | 12 (22.6) | 8 (8.1) | 7 (7.7) | ||

Cluster analysis by difficulty in treating AD.

Q: question; IQR: interquartile range.

The underlined figures indicate significant differences.

Non-parametric version of one-way analysis of variance.

Pearson’s Chi-squared test.

Kruskal–Wallis rank sum test.

Discussion

AD is a chronic disease requiring long-term management [10]. Both the practical skills of healthcare professionals and patient adherence to treatment plans are essential for successful treatment [11]. Many studies have evaluated the burden of disease on patients [12–14], but few have reported on the actual state of clinical practice, including satisfaction and difficulties experienced by physicians treating chronic diseases such as AD [15].

This survey was a landmark investigation that clarified the problems faced by physicians providing care for patients with AD. This investigation aimed to examine the current status of AD management and identify physicians who have difficulty managing this condition to improve the overall care provision.

Guidelines have been developed in Japan to resolve the confusion in AD practice [2], and these are continuously revised [5, 6]. A notable feature of the Japanese guidelines is that they describe the goal of treatment [6]. In this survey, many physicians reported reading the guideline (86.4%; >5 points), using it as a reference (87.6%; >5 points), and feeling that medical care of AD was rewarding (very rewarding 30% and somewhat rewarding 57.2%). This indicates that these guidelines play an important role in the management of AD.

However, the precise method for proactive therapy, an important remission maintenance therapy described in the guidelines, varies widely among physicians. These results indicate that proactive therapy is not an established method in clinical practice. To support its development, it may be necessary to develop and disseminate guidelines on the scope of application required, the timing of the transition from daily to intermittent application, and timing of completion.

The challenges identified in AD management included “low patient willingness to receive treatment,” “repeated deterioration and remission over time,” “increased consultation time per patient,” “low medical remission, exploration of deteriorating factors,” “management of mental aspects” and “understanding of patient’s adherence.”(10–13) These problems need to be resolved.

The respondents were divided into three clusters based on their perceived difficulty in managing AD patients. There were no differences in age, work location, specialty, and whether they read or used the guidelines. Although many physicians read and used the guidelines as a reference, there were also physicians who did so who often experienced problems in their practice (Cluster 3 [high-difficulty group]). Other support methods are required for these physicians.

When the three clusters were compared, the physicians in each cluster described similar problems, although the degree of difficulty varied. Therefore, we believe that providing support for items many physicians perceive as problematic will improve practices across all dermatologists. Therefore, we need to provide general problem-solving support for physicians who find it difficult to treat AD and support them in addressing items that many physicians perceive as problems, regardless of how difficult they find treating AD.

Significant differences were found between clusters in the responses to the question “Do you think it is possible to achieve good long-term control of AD?” (Q40) and “Please indicate your satisfaction and motivation for treating with atopic dermatitis on a scale of 10” (Q11). Physicians in the low-difficulty cluster believed that it was possible to achieve good long-term control of AD and showed higher satisfaction with and greater motivation to treat AD. These physicians were also significantly more likely to evaluate severity during the initial diagnosis and inspect the entire skin with the patient undressed at a return visit. This suggests that careful evaluation of the skin rash may affect the prognosis of patients and, in turn, improve ease of treatment and satisfaction with the management of AD.

The interpretation of the ‘curing of AD, a chronic disease, may differ among physicians. However, the results of this study suggest that physicians who experience less difficulty treating AD have more positive practice attitudes and treatment satisfaction. When physicians consider that “it is possible to achieve good long-term control of AD,” they achieve better treatment outcomes. In other words, differences in treatment goals affect physicians’ practice and patient outcomes. There is no international definition of “cured” for AD, but the final goal of treatment described in the Japanese clinical practice guidelines is to maintain a state of minimal to mild symptoms and avoid sudden deterioration that may interfere with daily life [6]. This may be one definition of a cure.

Many physicians in the high-difficulty cluster said they would like to use video educational materials, which may be useful for providing general problem-solving support. The content might include “evaluation of the severity as part of the initial diagnosis,” “inspecting whole skin of an undressed patient on a return visit” and “encouraging treatment with the goal of “long-term remission.”

Questions 12 and 14 suggest that solutions to the challenges that many physicians experience, irrespective of the cluster, would require greater awareness of specific methods used in proactive therapy. Further investigation is needed on balancing labor and medical service charges for an ideal AD practice. However, developing materials and patient guidance tools to reduce the workload may be useful. If patients express excessive anxiety about the use of topical corticosteroids and molecularly targeted drugs, materials that address these issues may be useful.

In the future, it is expected that patients’ problems will be understood before consultations using multiple patient-reported outcomes. Therefore, developing a system that provides patients with suitable guidance is possible. This system should encourage and motivate patients and healthcare workers.

Providing additional support may be costly; therefore, it is necessary to prove whether it reduces the overall cost of AD care. Other factors that may improve care provision include educating dermatologists on the psychosomatic approach to dermatology (Q12-10), developing a questionnaire on steroid anxiety (Q12-14), and developing a questionnaire on adherence (Q12-17).

Good communication between physicians and patients may improve patient satisfaction and lead to improved treatment adherence [16, 17]. One way to improve adherence is shared decision-making about treatment [18]. Among the items of guidance considered important by physicians for AD, the two top items are explanations of how to use topical ointments and knowledge about the disease [19, 20]. Therefore, it is important to determine patients’ preferences for treatment among the evidence-based therapies recommended in clinical practice guidelines. In the future, we will have access to materials and artificial intelligence to improve the efficiency of this process.

Limitations

Most survey respondents were dermatologists with an interest in skin allergies, and 70% were hospital physicians. Very few responses were received from the physicians or clinics responsible for dermatology in primary care settings. Future studies should repeat the same survey in a larger number and a wider variety of clinics.

Statements

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

This study was reviewed and approved by the Ethics Approval Committee of the JSCIA (approval date: 31 July 2019). The survey questions were presented after each respondent had read the purpose of the study and provided consent to use their data.

Author contributions

All authors participated in the design, interpretation of the studies and analysis of the data and review of the manuscript; SK, TN, HM, YK, and NK prepared and compiled the questionnaire; TK was responsible for statistical processing of the data; SK, TN, AT, HM, TK, YK, and NK wrote the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This study received partial support from the Atopic Dermatitis Section 2018–2020 of the Japanese Society for Cutaneous Immunology and Allergy.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the physicians of the Japanese Society for Cutaneous Immunology and Allergy for their cooperation in this study. We thank Melissa Leffler, MBA, from Edanz (https://jp.edanz.com/ac) for editing a draft of this manuscript.

Conflict of interest

SK received grants as an investigator and honoraria as a speaker from Eli Lilly, Japan. TN received honoraria as a speaker from Sanofi and Maruho. NK has received honoraria as a speaker/consultant from Sanofi, Maruho, Abbvie, Eli Lilly Japan, Taiho Pharmaceutical, Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma, and LEO Pharma and has received grants from Maruho, Sanofi, and Eli Lilly Japan. Sun Pharma; Taiho Pharmaceutical; Torii Pharmaceutical; Boehringer Ingelheim, Japan; and LEO Pharma. AT received honoraria as a speaker from Sanofi Eli Lilly, Taiho Pharma, Abbie, Mitsubishi-Tanabe, Torii Pharmaceutical, and Maruho and grants from Sanofi Eli Lilly, Taiho Pharma, Mitsubishi-Tanabe, Torii Pharmaceutical, and Maruho. HM has received honoraria as a speaker/consultant from Sanofi, Maruho, Taiho Pharmaceutical, Kaken Pharmaceutical, Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma, Japan Tobacco Inc., and Shiseido Co., Ltd. YK has received honoraria as a speaker from Sanofi and grants from Sanofi, Eli Lilly Japan, LEO Pharma, Maruho, Otsuka Pharmaceutical, and Pfizer.

The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

1.

Furue M Yamazaki S Jimbow K Tsuchida T Amagai M Tanaka T et al Prevalence of dermatological disorders in Japan: a nationwide, cross-sectional, seasonal, multicenter, hospital-based study. J Dermatol (2011) 38(4):310–20. 10.1111/j.1346-8138.2011.01209.x

2.

Yamamoto S Hide M Yamamura Y Morita E . [Investigation of folk remedies for atopic dermatitis]. A study report of research on immunology and allergy in Japanese Ministry of Health group research (1997).

3.

Furue M Chiba T Takeuchi S . Current status of atopic dermatitis in Japan. Asia Pac Allergy (2011) 1(2):64–72. 10.5415/apallergy.2011.1.2.64

4.

Takehara K . Problems associated with inadequate treatment for atopic dermatitis. Jpn Med Assoc J (2002) 45:483–9.

5.

Kawashima M Takigawa M Nakagawa H Furue M Iijima M Iizuka H et al Guidelines for therapy for atopic dermatitis. Jpn J Dermatol (2000) 110(7):1099–104. 10.14924/dermatol.110.1099

6.

Katoh N Ohya Y Ikeda M Ebihara T Katayama I Saeki H et al Clinical practice guidelines for the management of atopic dermatitis 2018. J Dermatol (2019) 46(12):1053–101. 10.1111/1346-8138.15090

7.

Simpson EL Bieber T Guttman-Yassky E Beck LA Blauvelt A Cork MJ et al Two phase 3 trials of dupilumab versus placebo in atopic dermatitis. N Eng J Med (2016) 375(24):2335–48. 10.1056/NEJMoa1610020

8.

Katoh N Kataoka Y Saeki H Hide M Kabashima K Etoh T et al Efficacy and safety of dupilumab in Japanese adults with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis: a subanalysis of three clinical trials. Br J Dermatol (2020) 183(1):39–51. 10.1111/bjd.18565

9.

Simpson EL Lacour JP Spelman L Galimberti R Eichenfield LF Bissonnette R et al Baricitinib in patients with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis and inadequate response to topical corticosteroids: results from two randomized monotherapy phase III trials. Br J Dermatol (2020) 183(2):242–55. 10.1111/bjd.18898

10.

Barbarot S Rogers NK Abuabara K Aubert H Chalmers J Flohr C et al Strategies used for measuring long-term control in atopic dermatitis trials: a systematic review. J Am Acad Dermal (2016) 75(5):1038–44. 10.1016/j.jaad.2016.05.043

11.

Murota H Takeuchi S Sugaya M Tanioka M Onozuka D Hagihara A et al Characterization of socioeconomic status of Japanese patients with atopic dermatitis showing poor medical adherence and reasons for drug discontinuation. J Dermatol Sci (2015) 79(3):279–87. 10.1016/j.jdermsci.2015.05.010

12.

Nakahara T Fujita H Arima K Taguchi Y Motoyama S Furue M . Perception gap between patients and physicians regarding disease burden and treatment satisfaction in atopic dermatitis: findings from an online survey. Jpn J Dermatol (2018) 128(13):2843–55. 10.14924/dermaol.128.2843

13.

Murota H Inoue S Yoshida K Ishimoto A . Cost of illness study for adult atopic dermatitis in Japan: a cross-sectional web-based survey. J Dermatol (2020) 47(7):689–98. 10.1111/1346-8138.15366

14.

Drucker AM Wang AR Li WQ Sevetson E Block JK Qureshi AA . The burden of atopic dermatitis: summary of a report for the national eczema association. J Invest Dermatol (2017) 137(1):26–30. 10.1016/j.jid.2016.07.012

15.

De Oliveira Vasconcelos Fiiho P de Souza MR Elias PE D’Avila Viana AL . Physicians’ job satisfaction and motivation in a public academic hospital. Hum Resour Health (2016) 14(1):75–86. 10.1186/s12960-016-0169-9

16.

Renzi C Abeni D Picardi E Agostini E Melchi CF Pasquini P et al Factors associated with patient satisfaction with care among dermatological outpatients. Br J Dermatol (2001) 145(4):617–23. 10.1046/j.1365-2133.2001.04445.x

17.

Furue M Onozuka D Takeuchi S Murota H Sugaya M Masuda K et al Poor adherence to oral and topical medication in 3096 dermatological patients as assessed by the Morisky Medication Adherence Scale-8. Br J Dermatol (2015) 172(1):272–5. 10.1111/bjd.13377

18.

Wilson SR Strub P Buist AS Knowles SB Lavori PW Lapidus J et al Shared treatment decision making improves adherence and outcomes in poorly controlled asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med (2010) 181(6):566–77. 10.1164/rccm.200906-0907OC

19.

Kaneko S Sumikawa Y Dekio I Morita E Kakamu T . Questionnaire-based study on the knack of medical personnel with regard to providing directives to outpatients with atopic dermatitis. Nishinihon J Dermatol (2011) 73(6):614–8. 10.2336/nishinihonhifu

20.

Kaneko S Kakamu T Sumikawa Y Ohara N Hide M Morita E . Questionnaire-based study of the doctor’s guidance for patients with atopic dermatitis. Jpn J Dermatol (2013) 123(11):2091–7. 10.14924/dermatol.123.2091

Summary

Keywords

atopic dermatitis, cross-sectional survey, Japan, dermatology practice, patient perceptions

Citation

Kaneko S, Nakahara T, Murota H, Tanaka A, Kataoka Y, Kakamu T, Kanoh H, Watanabe Y and Katoh N (2024) Physicians’ perspectives and practice in atopic dermatitis management: a cross-sectional online survey in Japan. J. Cutan. Immunol. Allergy 7:12567. doi: 10.3389/jcia.2024.12567

Received

14 December 2023

Accepted

19 February 2024

Published

14 March 2024

Volume

7 - 2024

Updates

Copyright

© 2024 Kaneko, Nakahara, Murota, Tanaka, Kataoka, Kakamu, Kanoh, Watanabe and Katoh.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Sakae Kaneko, kanekos3@masuda.jrc.or.jp

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.