- 1División de Estudios de Posgrado, Facultad de Ingeniería, Universidad Autónoma de Querétaro, Querétaro, Mexico

- 2Instituto Tecnológico Vale, Belém, Brazil

- 3Department of Physics, Center for Nanotechnology and Molecular Materials, Wake Forest University, Winston Salem, NC, United States

The intricate interplay between SMCs and agroecosystems has garnered substantial attention in recent decades due to its profound implications for agricultural productivity, ecosystem sustainability, and environmental health. Understanding the distribution of SMCs is complemented by investigations into their functional roles within agroecosystems. Soil microbes play pivotal roles in nutrient cycling, organic matter decomposition, disease suppression, and plant‒microbe interactions, profoundly influencing soil fertility, crop productivity, and ecosystem resilience. Elucidating the functional diversity and metabolic potential of SMCs is crucial for designing sustainable agricultural practices that harness the beneficial functions of soil microbes while minimizing detrimental impacts on ecosystem services. Various molecular techniques, such as next-generation sequencing and high-throughput sequencing, have facilitated the elucidation of microbial community structures and dynamics at different spatial scales. These efforts have revealed the influence of factors such as soil type, land management practices, climate, and land use change on microbial community composition and diversity. Advances in high-throughput methodological strategies have revolutionized our ability to characterize SMCs comprehensively and efficiently. These include amplicon sequencing, metagenomics, metatranscriptomics, and metaproteomics, which provide insights into microbial taxonomic composition, functional potential, gene expression, and protein profiles. The integration of multiomics approaches allows for a more holistic understanding of the complex interactions within SMCs and their responses to environmental perturbations. In conclusion, this review highlights the significant progress made in mapping, understanding the distribution, elucidating the functions, and employing high-throughput methodological strategies to study SMCs in agroecosystems.

Introduction

Despite significant progress, there remain critical gaps in our knowledge regarding the intricate interactions and functions of SMCs within agroecosystems. Addressing these gaps is paramount for several reasons: Firstly, sustainable agriculture, which is necessary due to the growing global population and increasing demand for food, meaning there is an urgent need to develop sustainable agricultural practices. Soil microbes are integral to soil health and fertility, influencing crop yield and quality (Wei et al., 2024). A deeper understanding of microbial dynamics can lead to the development of strategies that enhance soil health and promote sustainable agricultural practices. The second reason is environmental impact: agroecosystems are significant contributors to environmental changes, including greenhouse gas emissions, soil degradation, and loss of biodiversity. The goal of microbiome rescue is to initiate a resilience trajectory for community functions, which can be achieved through demographic, functional, adaptive, or evolutionary recovery of disturbance-sensitive populations. This process is supported by various ecological mechanisms such as dispersal, reactivation from dormancy, functional redundancy, plasticity, and diversification. These mechanisms can interact to enhance recovery, with controlling microbial reactivation from dormancy being a particularly promising but underexplored target for rescue efforts.

Plant and animal diversity, as well as fungal and bacterial communities, play vital roles in decomposition and humus formation both above and below the ground (Wood et al., 2015). Early studies on SMCs relied on culture-based techniques, which were limited in scope and often biased towards easily culturable organisms. These methods provided a basic understanding but lacked comprehensive insights into the vast diversity of soil microbes. Advances in cutting edge tools and statistical and computational biology have simplified SMC assessments (Herrera-Paredes and Lebeis, 2016). For instance, DNA-based techniques are used to assess SMC variation across geographical regions worldwide. Advancement of GIS and spatial analysis tools have been integrated with microbial data to map the distribution of soil microbes across different regions and agroecosystems (Sanad et al., 2024). Nevertheless, to determine microbiota function and interactions within SMCs, it is necessary to increase the spatial resolution of community analysis of individual aggregates and investigate microbial diversity in each spatial entity. Szoboszlay and Tebbe (2021) demonstrated that DNA extraction from each soil aggregate provides new insights into how SMCs are assembled. Furthermore, biochemical and molecular techniques provide information about the spatial stratification of microbial populations between the inner and outer layers of soil aggregates (Helgason et al., 2010; Mummey et al., 2006; Turner et al., 2017). Understanding soil microbial aggregates is crucial for comprehending the structural organization of SMCs within the soil matrix. Microbial aggregates are clusters of microorganisms bound together by extracellular substances such as polysaccharides and proteins (Rillig et al., 2019). These aggregates play essential roles in soil fertility, nutrient cycling, and overall soil health. By connecting these, we can infer that assessing SMCs provides insights into the composition and functioning of microbial aggregates, elucidating their roles in soil ecosystem processes. This integrated approach enhances our understanding of soil microbial dynamics and their impact on soil health and ecosystem functioning.

Many case studies have shown that crop-associated beneficial microbes (bacteria, fungi, and actinomycetes) could be associated with disease-suppressive soil against pathogens (Kurm et al., 2023; Xiong and Lu, 2022). This phenomenon could suppress soil-borne plant diseases, often without the need for synthetic chemical interventions. This suppression occurs due to the activities of beneficial microorganisms present in the soil, which antagonize or outcompete pathogenic organisms, thereby reducing their populations or preventing their proliferation. This process is involved in the complex interplay of various factors, including competition for nutrients, the induction of plant defenses, the alteration of soil physicochemical properties, and the production of antimicrobial compounds. For instance, some bacteria and fungi produce antibiotics or secondary metabolites that inhibit the growth of pathogens. Others may compete with pathogens for space and nutrients, limiting their establishment and spread. Additionally, certain beneficial microbes can form symbiotic relationships with plants, enhancing their resistance to diseases by stimulating plant immune responses or directly antagonizing pathogens. Studies have demonstrated the significance of disease-suppressive soil in sustainable agriculture by reducing the reliance on chemical pesticides and fertilizers while promoting plant health and productivity (Mendes et al., 2011). Harnessing the potential of crop-associated beneficial microbes and understanding their interactions within the soil microbiome are critical for developing strategies to enhance disease-suppressive soil and improve agricultural sustainability.

Conversely, a broad range of edaphic variables, such as soil salinity, soil pH, organic carbon (C), types of soil, redox potential, and nutrient availability [(N), (P), and (S)], influence the diversity of SMCs (Ashworth et al., 2017; Jackson et al., 2012; Chaparro et al., 2012; Xu et al., 2013; Pasternak et al., 2013). Essentially, N cycling is involved in the nitrogen fixation, nitrification, and denitrification processes. C cycling is engaged in the decomposition of organic matter and contribution to the soil organic carbonic pool. Phosphorus solubilization is used to make phosphorus available to plants. SMCs play a pivotal role in mitigating these impacts through processes such as carbon sequestration and nutrient cycling (Wu et al., 2024). Recent research has discussed the taxonomical and functional dynamics of SMCs and their involvement in the processes of N fixation, organic matter decomposition, degradation of organic pollutants, and plant‒soil interactions (Cascio et al., 2021; Farzadfar et al., 2021). However, temperature, moisture, and seasonal variations also impact microbial activity and distribution. For example, climate change poses a significant threat to agricultural productivity and sustainability (Yuan et al., 2024). Soil microbes are key players in maintaining soil structure and function under changing climatic conditions. Understanding how microbial communities respond to climate change is essential for developing resilient agroecosystems (Shade, 2023). Additional factors such as land management, which involves crop rotation, tillage, irrigation, and fertilization practices, alter the soil environment and microbial habitats.

These reports further support the use of advanced methodological strategies (microbiome engineering) to improve the quality and quantity of food for the future population. Therefore, it is necessary to understand the fundamental mechanism of soil‒plant‒microbe interactions, and worldwide mapping of SMC diversity and functional importance, such as biogeochemical transport, organic management, and disease suppression, is needed in different agroecosystems. On the other hand, methodological strategies can be used to identify links between soil nutrients and bacterial and fungal allocation as well as spatial changes in biological processes (Li Y. et al., 2023; Gupta and Germida, 2015). Various approaches have been employed to investigate the composition of SMCs and their response to changes in different environments (Ligi et al., 2014; Vanwonterghem et al., 2014). This information allows for the identification of relationships between microbial aggregate properties and organic matter distribution. Metagenomic analysis can provide descriptions of both taxonomic and functional SMC assemblages in natural environments and their potential roles in ecosystems (Maron et al., 2011). For instance, a meta-analysis showed a 15.1% increase in microbial taxa (microbial phyla/classes) and a 3.4% increase in microbial diversity in crop rotation cultivation compared to single crop cultivation (Venter et al., 2016). The complexity of SMCs and their interactions with plants, soil, and the environment necessitate a multidisciplinary approach. There is a need for long-term and large-scale studies to capture the temporal and spatial dynamics of SMCs. Recent studies can provide insights into how SMCs respond to agricultural practices, environmental changes, and management interventions over time (Kabir et al., 2024). The variability in methodologies and data interpretation across studies poses a challenge for comparing and synthesizing research findings. Developing standardized protocols for sampling, data analysis, and reporting can enhance the reproducibility and comparability of soil microbiology studies. Although significant progress has been made in identifying microbial taxa, there is still a limited understanding of the functional roles of many soil microbes. Over the last 10 years, environmental genomic techniques have provided a much better understanding of microbial composition, yet detailed data about microbial populations are still lacking in areas such as community-environment interactions and species-species interactions.

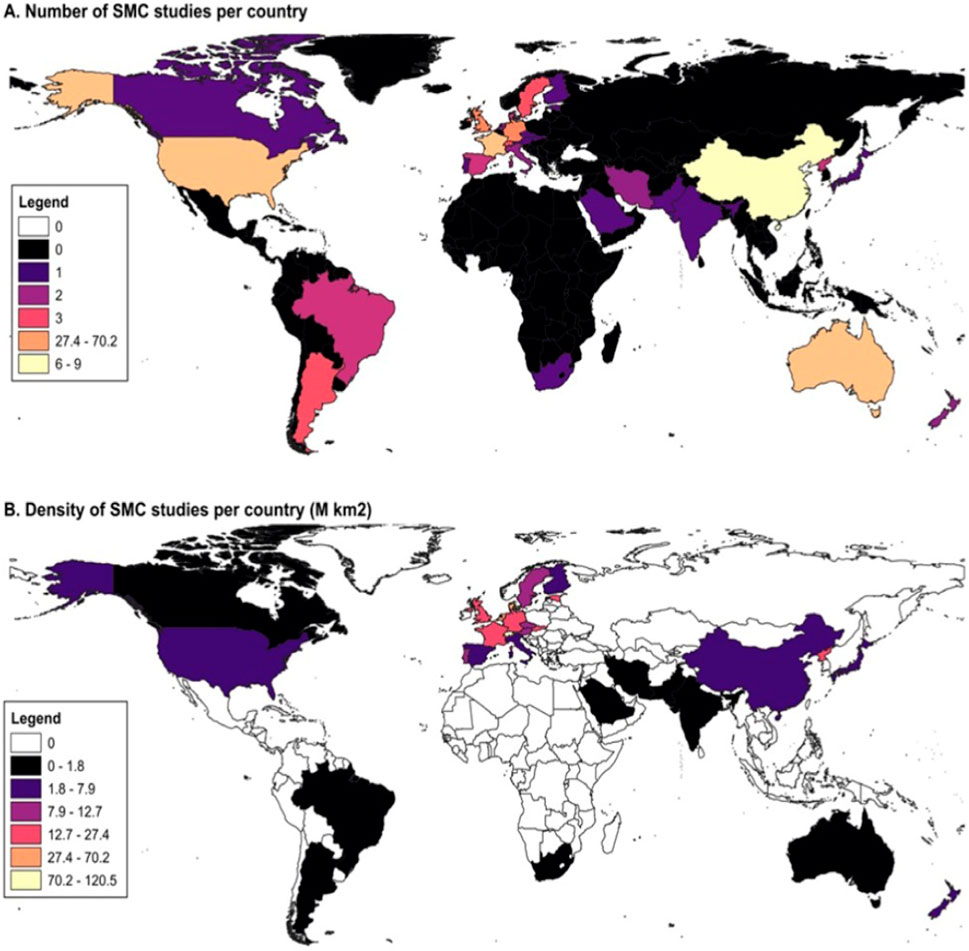

Materials and Methods: Scientific Publication of Global Research on SMCs

Some reports examine the spatial variability of microbial communities across different climatic conditions, land uses, and agricultural practices. A study by Du et al., 2023 found that microbial community compositions at various taxonomic levels (e.g., species, genus, family) exhibit relatively consistent distribution patterns and mechanisms. These outcomes suggest that geographic or spatial factors play a crucial role in shaping microbial distributions. Consequently, this review was constructed from a comprehensive electronic database search for specific terms such as “soil microbial diversity,” “disease suppressive soil,” “soil nutrient promoter,” “plant growth nutrients,” “molecular ecological characterization,” and “agricultural management.” In this review, we collected 395 observations from 182 studies to examine the geographical distribution of soil microbes unevenly across climate zones and continents. All references were organized in a Microsoft Excel TM spreadsheet (see Supplementary Material). The articles were classified based on publication year, country of origin (experimental zone), and affiliation of the corresponding author. Consequently, this review explores the mapping, distribution, function, and cutting-edge strategies used by SMCs in agroecosystems, especially in the years 2000, 2008, and 2012. The data were obtained from the following electronic databases:1-10. Figure 1A shows the number of SMC studies per country, and (Figure 1B) shows the density of SMC studies per country (M km2) (see the Supplementary Material). Supplementary Figure S1 shows the global studies on SMCs promoting sustainable ecosystems between 2011 and 2020. Supplementary Figure S2 displays the top specific journals published in the investigation of soil microbial community diversity, function, and methodology strategies obtained from the abovementioned editorial databases.

Figure 1. Mapping shows the distribution (absolute and in relation to size of different states - density) of SMCs across the globe. (A) shows the number of SMC studies per country, and (B) shows the density of SMC studies per country (M km2).

Integration of GIS

Recent advancements in spatial mapping technologies and the integration of GIS have significantly enhanced our ability to study and understand microbial community distribution in soil ecosystems (Guseva et al., 2022). Recently, Li et al. (2024a) designed the Microgeo to enable visualization of SMC traits on geographical maps, especially on large or unevenly distributed spatial scales Meanwhile, He et al. (2023) offered important insights into how land use changes impact SMC composition and diversity, offering a theoretical basis for understanding microbial dynamics in river basins. Spearman analysis and redundancy analysis (RDA) were used to examine correlations between soil properties and microbial community composition; Partial least squares path model (PLS-PM) was used to express causal relationships between soil properties and microbial diversity. Kalaimurugan et al., 2019; Arumugam et al., 2022 employed GIS to analyze the spatial distribution of SMCs across different land use types, revealing how land management practices influence microbial diversity and abundance. Finding and integrating microbial community data with GIS, researchers can map microbial populations and their associations with environmental variables. Additionally, GIS combined with machine learning and statistical modeling allows for predictive mapping of microbial communities based on environmental data. These models can forecast microbial distribution patterns under various scenarios, such as climate change or land management practices (Diaz-Gonzalez et al., 2022). Furthermore, Beatty et al., 2021 used remote sensing technologies to provide data on soil properties from a distance, allowing for the large-scale monitoring of soil health and microbial communities.

Microbiome in Soil

In the soil microbiome, bacteria and fungi are the most abundant organisms, and their presence is essential for the regulation of plant growth. Interestingly, SMCs act as sources of essential nutrients, enzymes, and other biochemical compounds essential for the growth and development of plants, animals, and microorganisms. Moreover, SMCs are involved in the decomposition of organic matter, releasing nutrients that plants can take up, thus contributing to soil fertility. Additionally, certain microbial species produce bioactive compounds with beneficial properties, such as plant growth-promoting hormones or antibiotics, that can suppress plant pathogens. These microbial-derived substances can be harnessed for agricultural practices to enhance crop productivity and health. On the other hand, SMCs also serve as reservoirs of biodiversity and genetic diversity, which play crucial roles in ecosystem resilience and adaptation to environmental changes. Moreover, soil microbes play roles in biogeochemical cycles, such as carbon, nitrogen, and phosphorus cycling, which are fundamental processes for sustaining life on Earth. The genetic diversity within SMCs represents a vast reservoir of potential traits and functions that can be exploited for various applications, including bioremediation, rhizosphere biology, and biotechnology. Recently, Banerjee and van der Heijden (2022) demonstrated that SMCs function as sources and reservoirs for healthy soils, plants, and animals and humans. In this report, the authors determined that SMCs directly and indirectly support fundamental soil processes and functions through organic matter decomposition, N fixation, C transformation and cycling, and soil structure maintenance.

A meta-analysis of SMCs revealed that the biogeography of microorganisms is driven by variables that differ from those of macroorganisms (Dequiedt et al., 2011). In fact, SMCs are structurally dependent on local factors rather than large-scale factors such as geographic isolation (Ranjard et al., 2013). However, Fernandez et al. (2016) suggested that soil physicochemical test values, along with bacterial family and phylum abundances, provided a better explanation of the variation in soil functional profiles than did physicochemical test values alone. This result shows that derived SBC profiles might be useful tools for site-specific predictions of the effects of fertility management and crop-related soil functions. SBCs display distinct levels of rhizosphere compartments that decrease from the bulk soil toward the roots (Donn et al., 2015; Fan et al., 2017). Similarly, in rice and grapevines, the root and plant-tissue-associated communities represent a subset of the bulk soil community (Edwards et al., 2015; Zarraonaindia et al., 2015). However, smaller microbial network structures in rhizospheres than in bulk soil were observed in short-term plantations (Mendes et al., 2014). Davinic et al. (2012) examined the connection between SBC quality and the quantity of organic C in different fractions. According to the results of the present study, the less dominant bacterial taxa exhibited stronger interactions with specific chemical functional groups than did the more dominant bacterial taxa. Trivedi et al. (2016) revealed that gene abundance, SBC taxonomic composition, and soil organic matter quantity are linked to C-degrading enzymes.

The abundances of several bacterial phyla and fungal taxa increased in soils fertilized with manure. Additionally, many studies have reported that nitrogen availability largely affects SBCs and SFCs (Carrara et al., 2018). Ruamps et al. (2011, 2013) suggested that fungal use of C substrates in smaller pores was greater than that of bacteria because of fungi’s ability to spread via hyphal growth. Consequently, pore size, microbial community structure, geometry, and connectivity can significantly affect habitat suitability for microbial growth. Further studies have shown that PLFA biomarkers for AMF are relevant to composted green waste as well as persistent organic management (Lori et al., 2017; Moeskops et al., 2012). Another viewpoint suggests that temperate forest trees associate with fungal communities (AMF or ECM) to increase their access to nutrients and water availability, thus altering soil C and nutrient cycling (van der Heijden et al., 2015). In tropical forests, SFCs exert a strong influence on the ratio of inorganic to organic soil N (Waring et al., 2013), and the effects of ECM on N cycling enable the monodominance of tree species in tropical montane forests (Corrales et al., 2017).

Agroecosystem Microbiome

In agro-systems, SMCs provide a wide variety of functions (such as biogeochemical nutrient cycling and amendments) and benefits (pathogen resistance) to crop growth and health (Arif et al., 2020; Singh et al., 2020). Recent advances in multiomics methods have supported studies of SMC diversity, composition, and function in soil (Xiong and Lu, 2022; Matsumoto et al., 2021; Xu et al., 2021a). Multiomics studies suggest that sorghum carries multiple genes related to iron-chelating agents in the rhizosphere root system under drought stress (Xu et al., 2021b).

Biogeochemical Transport

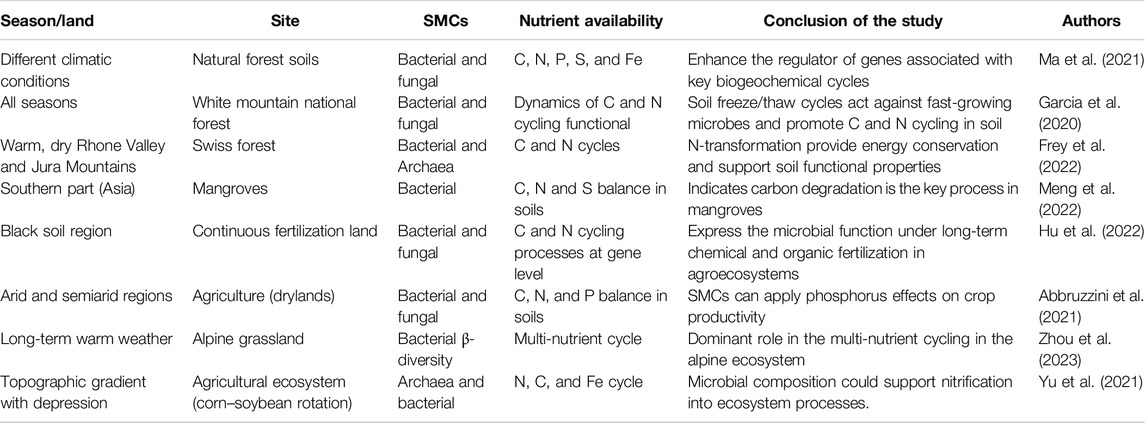

SMCs play a vital role in biogeochemical transportation for soil nutrient (N, P, and S) enrichment to facilitate plant growth. Recently, Gholizadeh et al. (2024) focused on how plants and their associated microbiome create intricate networks within the soil environment. These networks are influenced by a myriad of factors, including soil properties, host traits, and environmental conditions like drought. Understanding these interactions is crucial, as they have significant implications for carbon and nutrient cycling in the soil and, ultimately, for plant growth and fitness. These studies may encourage the implementation of soil management practices that enhance the growth of beneficial microbes and improve soil health. This might include practices like reduced tillage, organic amendments, and cover cropping. For example, in a forest ecosystem, comparative metagenomics analysis was used to quantify the soil microbiome involved in nutrient cycling in three tree species: ECM-associated Quercus rubra and Castanea dentata and AMF-associated Prunus serotina. Here, the results showed that tree species can deliver functional genes corresponding to N and C metabolism changes due to disease management (Kelly et al., 2021). Moreover, oilseed crops transport N-cycling genes such as the ammonia monooxygenase gene (amoA) and exhibit different patterns of expression between bacteria and archaea (Wang, et al., 2020). According to Wu et al. (2021), soil microbiomes contribute to N and P cycling in soil aggregates under different organic material amendments according to a genome-centric metagenomics approach. Interestingly, Li et al., 2024b introduced a new concept (Micro-Habitat) for understanding soil carbon (C) processing within an intact, undisturbed soil matrix. These reports provide quantification of each microhabitat, including soil physical (pore structure), biochemical, and biological (microbial traits) properties with microbial functional traits and carbon transformations. Table 1 shows a case study of SMCs involved in soil biogeochemical processes under various climatic conditions and promoting soil functions via the use of amplicon (rDNA) and metagenome sequencing methods (positive effects on forest and agriculture land was displayed).

Table 1. Case study of SMCs involved in soil biogeochemical processes under various climatic conditions and promoting soil functions via the use of amplicon (rDNA) and metagenome sequencing methods (positive effects on forest and agriculture land was displayed).

Disease Suppressive Soil

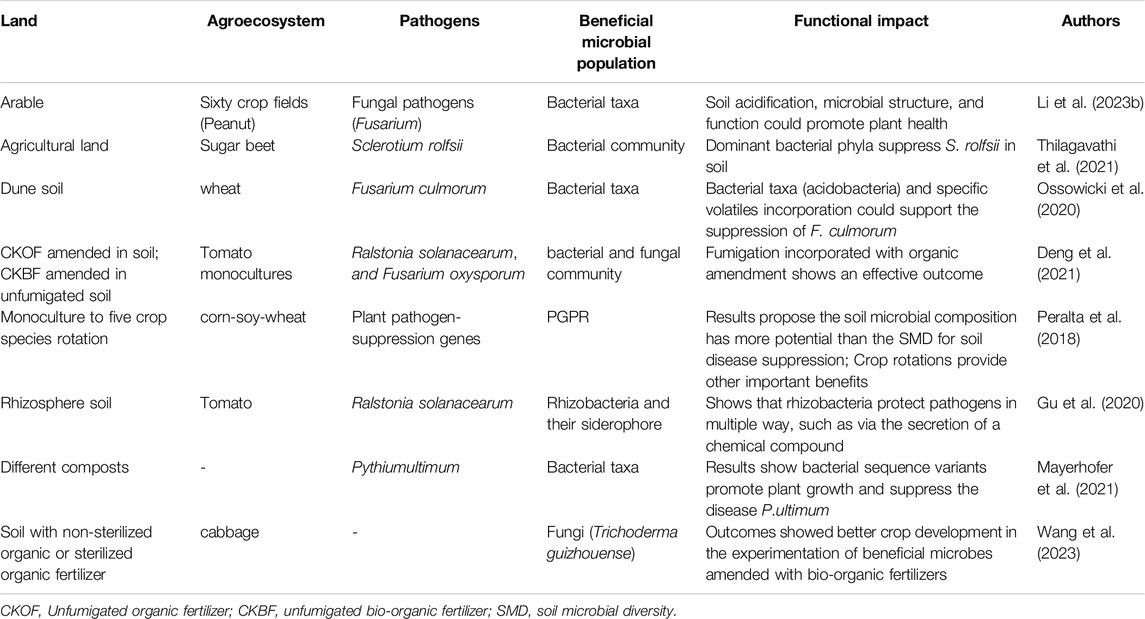

A disease-suppressive soil system offers effective protection from soil-borne pathogens because it has a beneficial microbial density with antimicrobial effects against pathogens and other natural plant defense traits. Tracanna et al. (2021) reported that nonribosomal peptide synthetase, which combines functional amplicon and 10x metagenomics tools, significantly promotes the production of iron-chelating agents secreted by the rhizosphere bacterial community within two different soil structures (suppressive and conducive) and evaluated disease suppression against Fusarium culmorum in wheat. Similarly, Nisrina et al. (2021) showed that PGPR can suppress fungal pathogens in the soil via competence and antibiosis mechanisms. Additionally, microbiome analyses indicated that phosphate solubilization, siderophore production, and nitrification bacteria can contribute to the suppression of fungal pathogens. Furthermore, recent studies have improved our understanding of the microbiome (bacteria and fungi) assembly and function of chili pepper under Fusarium wilt disease both above and below ground (Gao et al., 2021). Table 2 shows that accounting for the beneficial microbial population helps disease-suppressive soil function in various agroecosystems, as explored by amplicon (rDNA) and metagenome sequencing methods (functional impact on fruit and vegetable land studies was demonstrated).

Table 2. Beneficial microbial populations help disease-suppressive soil function in various agroecosystems, as explored by amplicon (rDNA) and metagenome sequencing methods (Functional impact on fruit and vegetable land studies was demonstrated).

Organic Amendments

Organic amendments are materials derived from organic sources, such as compost, manure, or plant residues, that are added to soil to improve its fertility, structure, and microbial activity. These amendments can have profound effects on SMCs. Undoubtedly, SMCs are more amenable to organic matter decomposition, nutrient availability, and biodegradation. Recent research by Liu et al. (2023) investigated the positive effects of organic amendments on SMCs in agricultural fields. The study showed that organic amendments significantly increased microbial biomass and activity, as well as the abundance of specific microbial taxa involved in nutrient cycling processes. Additionally, Yu et al. (2019) utilized biochar-amended soil microbiomes to cause significant shifts in composition and predicted metabolism. The key findings were carbon turnover, which involves plant-derived carbohydrates, and denitrification under biochar amendment. However, Alawiye & Babalola (2022) explored SMC composition, structural diversity, and plant growth functional genes in the sunflower rhizosphere and bulk soil. Metagenomic analysis revealed that the dominant phyla (Actinobacteria and Proteobacteria) produce multiple enzymes with plant-beneficial genes corresponding to nitrogen fixation, siderophore production, 1-aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylate deaminase, phosphate solubilization, and heat and cold shock. Coupling these functional genes with biotechnological applications such as biocontrol and fertilizers may aid in the development of improved food production. Cania et al. (2019) employed shotgun approaches to obtain bacterial microbiomes in three soil layers under RT and CT. In their analysis, specific gene production and expression for soil stabilizing agents (exopolysaccharides and lipopolysaccharides) were described. Moreover, Cui et al. (2020) confirmed that long-term mulberry production greatly improved the beneficial bacterial community structure for soil quality management. Remarkably, Akinola et al. (2021) carried out metagenomics approaches that identified plant-beneficial bacteria found in rhizosphere soil, including Bacillus spp., Pseudomonas spp., Streptomyces spp., Gemmatimonas spp., Conexibacter spp., Burkholderia spp., Gemmata spp., Mesorhizobium spp., and Micromonospora spp.

General Panorama of Soil Microbial Function (Nutrient Cycling and Mineralization)

The Shannon, Simpson, dominance, and evenness indices are used to describe the alpha diversity of microbial communities (Dubey et al., 2016; Haegeman et al., 2013). The Simpson (D) index can determine whether two individuals randomly selected from a sample belong to the same species (Pathan et al., 2015). The Shannon (H) index characterizes species diversity. It provides indicators for both the abundance and evenness of microbial species (Faoro et al., 2010); evenness is used to measure the relative abundances of various species (Thébault et al., 2014). These observational studies investigated changes in soil abiotic properties along with SMC structure and composition changes from lower to higher altitudes at three vegetation sites (Nothofagus betuloides, N. pumilio, and alpine). The data show that increases in the soil C:N ratio at alpine sites were associated with shifts from bacterial dominance at lower altitudes to fungal dominance at higher altitudes. This can be attributed to several interrelated factors, such as temperature, substrate availability, soil pH, nutrient availability, and plant‒microbe interactions. First, moisture conditions often favor fungal dominance over bacterial dominance, as fungi are generally more efficient at decomposing complex organic matter under colder temperatures and lower moisture conditions. Additionally, the types of organic matter available for decomposition can vary with altitude due to differences in vegetation composition and productivity. At lower altitudes, where plant litter tends to be fresher and more labile, bacterial populations thrive due to their ability to rapidly metabolize simple organic compounds. In contrast, at higher altitudes, where plant litter may be more recalcitrant and dominated by tougher materials such as lignin and cellulose, fungi are better equipped to break down these complex compounds through their extracellular enzymes. Moreover, soil pH tends to decrease with increasing altitude due to factors such as decreased microbial activity and increased leaching of fundamental cation exchange capacity. Fungi generally thrive in acidic environments, whereas many bacterial species prefer neutral to slightly alkaline conditions. This shift in soil pH can favor fungal dominance at relatively high altitudes. Consequently, the functional properties of vegetation communities may influence SMCs. The relationship between biodiversity and ecosystem function is relevant to agricultural ecosystems (de Menezes et al., 2015; Constancias et al., 2015). This interaction influences key processes such as nutrient cycling, pest regulation, and crop productivity. Studies have shown that diverse plant communities can increase soil organic matter content and nutrient availability, leading to higher crop yields (Eisenhauer et al., 2017). Several studies have explored the associations of Proteobacteria, Actinobacteria, and Bacteroides bacteria with copiotrophic behaviors and Verrucomicrobia, Firmicutes, and Acidobacteria bacteria with oligotrophic behaviors (Goldfarb et al., 2011). Microbial coherence is directly related to soil bacterial taxa. For example, soil bacterial taxa are influenced by a wide range of environmental factors, including pH, moisture, temperature, nutrient availability, and organic carbon content. These environmental drivers shape the composition and structure of SMCs, leading to patterns of coherence or divergence among bacterial taxa across different soil types, land uses, or management practices. Moulin et al. (2023) assessed the impact of different agroecological practices on the composition and diversity of bacterial and fungal communities in the soil. Their results showed enhanced beneficial soil bacteria, particularly Actinobacteria. These effects positively impact soil health by enhancing microbial diversity and enriching soil with nutrients.

The abundances of “copiotrophic” Betaproteobacteria and Bacteroides are linked to increased rates of soil C mineralization, while “oligotrophic” Acidobacteria are correlated with decreased rates of soil C mineralization (Finn et al., 2017). Actinobacteria play important roles in organic matter turnover, and the breakdown of recalcitrant molecules (cellulose and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons) has been characterized by two-bacterium models (Thermobifida fusca and Cellulomonas fimi) (de Menezes et al., 2012). Consequently, microaggregates of Rubrobacteriales represented a small portion of the total organic C, whereas other Actinobacteria (excluding Rubrobacteriales) and Alphaproteobacteria were abundant in macroaggregates, making up the majority of the soil organic C.

Cutting Edge Tools and Techniques for Elucidating Soil Microbiota

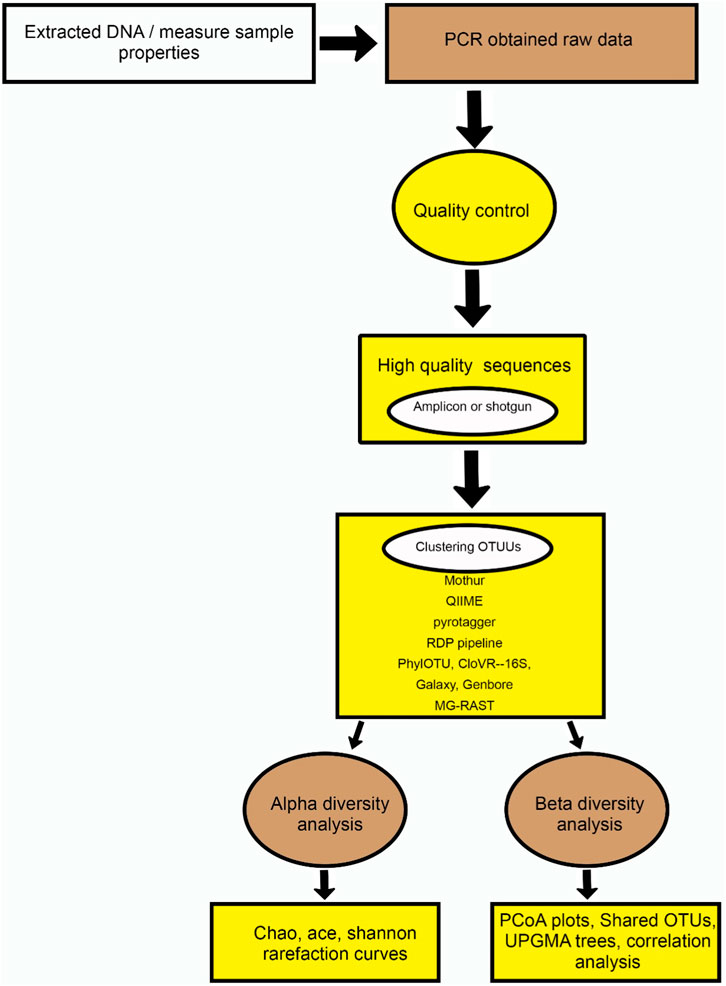

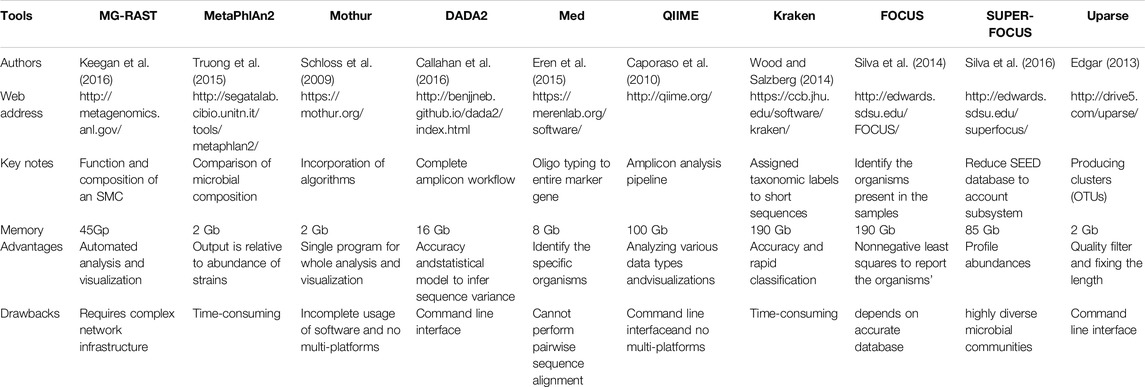

SMCs play a significant role in global element cycling, organic matter turnover, xenobiotics breakdown, and soil aggregate formation. Unlike plant, macro, and meso fauna diversity, soil microbial diversity has only recently been studied (Mamabolo et al., 2024). Traditional microbiological cultivation techniques failed to characterize most soil microorganisms, but cultivation-independent methods have expanded our understanding. These methods include direct DNA extraction from soil for molecular marker gene analysis and molecular techniques to study microbial functions in situ. The phospholipid approach, analyzing membrane components for taxonomic differentiation, complements genotypic methods and is well-established in soil ecology. In this aspect, functional metagenomics begins with the separation of DNA from ecosystem SMCs. There are two steps to understanding how these genes function in soil nutrient elevation. First, amplification is necessary, and 16S rDNA gene meta-transcriptomic and metaproteomic data are obtained from the soil microbiome. We identified specific genes of interest that are involved in nutrient cycling, nutrient uptake, or other relevant processes related to soil nutrient elevation. These genes could include those encoding enzymes involved in nitrogen fixation, phosphorus solubilization, and carbon mineralization. Bioinformatics tools are essential for acquiring all necessary information from the procedures mentioned above (Ortiz-Estrada et al., 2019). Second, molecular shotgun sequencing or denominated whole-metagenome shotgun sequencing of SMC genomic DNA is needed. However, with the increased use of high-throughput sequencing methods, the accessibility of genome data plays a significant role in functional metagenomics studies (Lam et al., 2015; Garibay-Valdez et al., 2020). Figure 2 establishes the overview of meta-genomics approaches on soil microbial diversity. This sequencing technique involves randomly fragmenting the amplified DNA into small pieces, sequencing these fragments using high-throughput sequencing platforms, and then assembling the sequenced fragments into longer contigs or scaffolds. Table 3 lists key bioinformatics tools that provide information for the functional metagenomics of a microbiome.

Table 3. Key bioinformatics tools that provide information for the functional metagenomics of a microbiome.

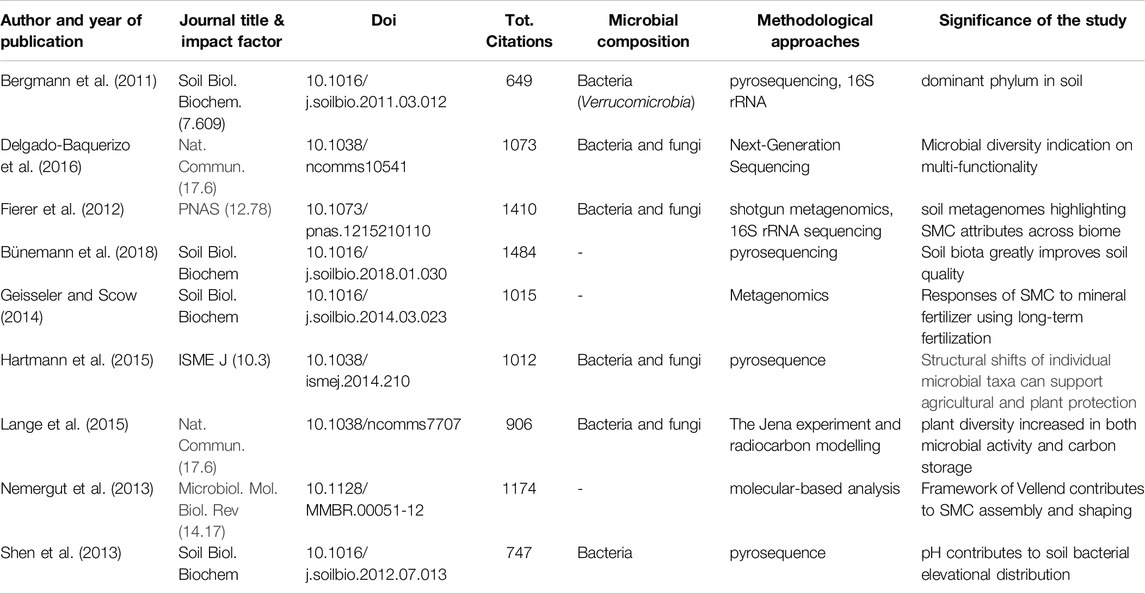

Shotgun metagenomics analyses became possible due to the development of several bioinformatics tools (Illumina protocol) that can be used to generate databases [e.g., CAZYmes (Cantarel et al., 2009), MG-RAST (Meyer et al., 2008), MEGAN 5 (Mitra et al., 2011), and RDP (Cole et al., 2003)]. Table 4 shows the top journal publications employing soil metagenomics approaches based on the total number of citations. Functional metagenomics tools require sequence alignment with a large database of annotated sequences to identify homologs (Mendoza et al., 2015). Unfortunately, many bioinformatics tools for functional profiling are slow; Lind Green’s group suggested a need for improved speed and accuracy of metagenomics tools (Lindgreen et al., 2015). Homology-based pre-NGS tools such as BLAST match suitable sequence alignments in a large database, while other homology search tools such as RAPSearch2 (Zhao et al., 2012) and DIAMOND (Buchfink et al., 2015) have also been established to reduce run time. On the other hand, exact match or k-mer-based tools use oligonucleotides to identify the best match in a metagenome. For instance, Edwards’s group found all words of length k-mer-related proteins using real-time RTMg (Edwards et al., 2012). This approach can assign taxonomic labels to metagenomic sequences (Ounit et al., 2015). Recently, SUPER-FOCUS tools were used to identify subsystems in metagenomic samples that show taxonomical conservation and functional adaptation (Silva et al., 2016). Compared to standard metagenomics pipelines (e.g., RTMg and MGRAST), SUPER-FOCUS speeds up the three-way sequence functional annotation process via SEED database clustering, querying sequences in FOCUS and performing comparisons using RAPSearch2. Additionally, Kraken and Anvio are feasible options for relatively fast analysis of bacterial community functions. With high-performance analytical hardware (128 Gb RAM Linux server), SUPERFOCUS may sacrifice accuracy and detail for speed. The relevant data obtained from these methods open new doors for understanding soil microbiomes. Although amplicon-based profiling does not provide a direct measure of microbial community function, information about SMC composition can help predict crucial soil functions such as nutrient cycling (Graham et al., 2016; Weedon et al., 2017; Callahan et al., 2019). These studies indicate that soil function is primarily dependent on the connection between microbial composition and the improvement of biogeochemical cycling. Global changes associated with alterations in the phylogenetic composition of the bacterial community support this conclusion.

Table 4. Top journal publications employing soil metagenomics approaches based on the total number of citations.

Protocols for sequencing and QIIME bioinformatics pipelines for the analysis of 16S rDNA data are becoming increasingly well established and, with sufficient sequencing depth, can yield detailed phylogenetic profiles of both abundant and rare taxa (Caporaso JG et al., 2010; Boon et al., 2014). QIIME was used to estimate distances between communities (both taxonomic and phylogenetic metrics). Perhaps the gold standard for microbial diversity units is the commonly accepted “operational taxonomical unit” (OTU) for the analysis of AVS (amplicon sequence variant). (Schmidt et al., 2014). For instance, the ecotype model of bacterial speciation describes basic diversity units since ecologically coherent group diversity is limited by cohesive genetic forces. Dedicated algorithms exist to demarcate ecotypes from environmental sequencing data (Koeppel et al., 2008).

PLFA measurements were performed to infer the functional capacity of microbial communities, while enzyme assays, respiratory measurements, or substrate utilization assays were used to measure the functional activity of SMCs (Liang et al., 2019). Multivariate analysis contributes to microbial ecology by assessing variance, aiding in understanding relationships in constraint variables and describing discriminant functions (Paliy and Shankar, 2016). According to Guan et al. (2018), fatty acid profiling followed by multivariate statistical analysis has been used to study SMC structure under different agronomic regimes because different microbial taxa contain fatty acids that vary in their chain lengths, numbers of unsaturated bonds, and positions of double bonds (Bowles et al., 2014; Liu et al., 2012).

Strengths and Limitations

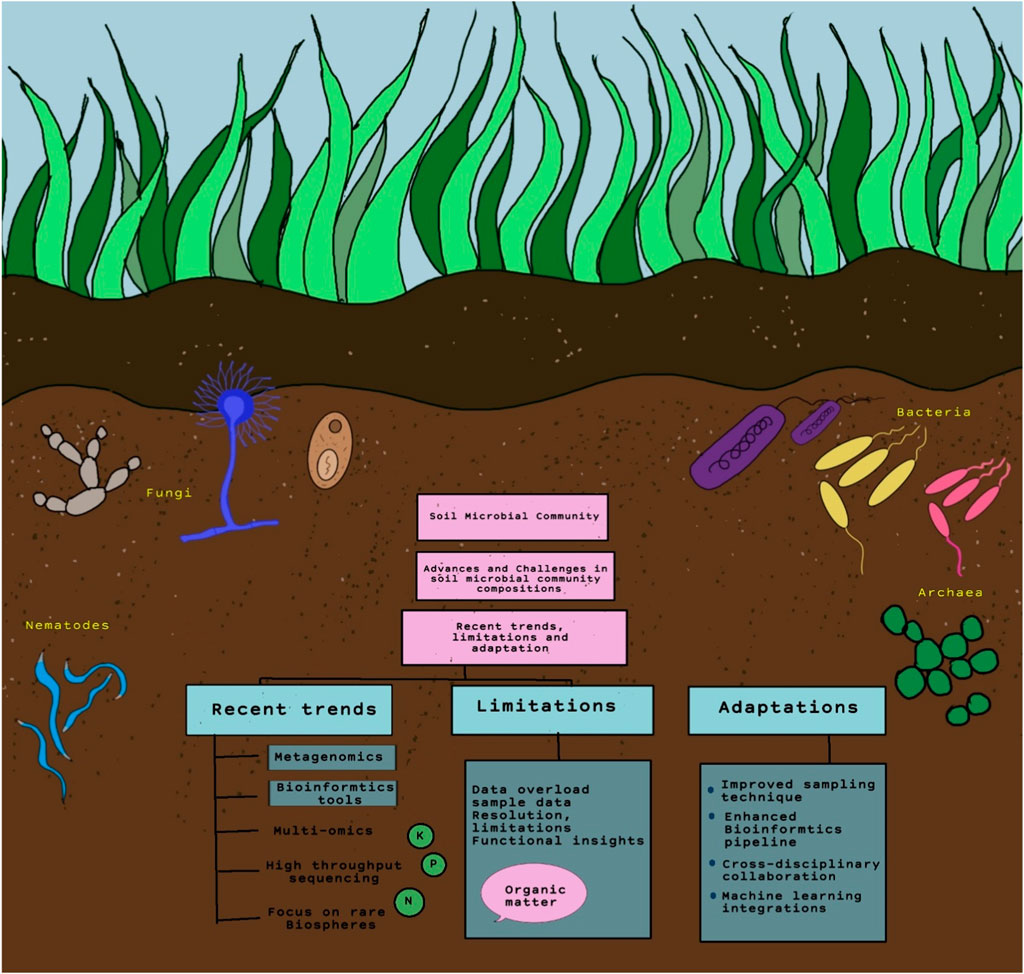

This review describes the multidisciplinary approach that allows for a comprehensive understanding of SMC and their interactions within agroecosystems. Recent decades has seen advancements in mapping techniques, distribution models, functional analyses, and high-throughput methodologies. For example, high-throughput methodologies are crucial for generating large-scale data, enabling detailed insights into microbial community dynamics. Similarly, emphasizing the function of SMC in agroecosystems can offer practical implications for agriculture. Certainly, some studies may not encompass a broad range of agroecosystems. Figure 3 demonstrates the recent trends, limitations, and adaptation to methodology related to SMC composition. However, SMCs can vary significantly over time due to seasonal changes, agricultural practices, and environmental conditions, which may not be fully captured in single-timepoint studies. Though high-throughput sequencing methods have revolutionized soil microbiome studies, there are still challenges such as PCR biases, DNA extraction methods, and bioinformatics pipelines that could impact data accuracy and comparability. While there is a growing body of literature on microbial community composition, understanding the functional roles of different microbial taxa in agroecosystems remains a challenge. It is necessary to address the challenges of handling and integrating large-scale data from high-throughput methods, including bioinformatics and statistical issues. Though issues such as difficulties in scaling studies from laboratory to field settings and the need for more refined spatial and temporal resolution, bridging the gap between fundamental research and practical applications is essential for translating scientific findings into actionable strategies for farmers and land managers. Collaborations between researchers, agricultural stakeholders, and policymakers can facilitate the implementation of microbial-based solutions in agroecosystems.

Figure 3. Illustration of recent trends, limitations, and adaptation to methodology related to SMC composition.

Discussion

The high diversity of SMCs in agroecosystems makes maintaining soil quality challenging because of the numerous important soil processes. These assessments emphasize the need to develop and improve methodological strategies and guidelines to protect SMCs based on important environmental drivers, such as plant nutrient use, land conversion, nitrogen enrichment, climate change, and soil microbial diversity monitoring programs. Methods are available, but researchers and future stakeholders should mobilize to develop standards for soil collection and SMC analysis that can close these gaps and provide reliable information about the status of SMCs. Furthermore, the effects of land use changes, climate change, and further ecosystem degradation on communities responsible for crop production and a wide range of other ecosystem services must be determined. With continued sequencing and identification of taxa, the challenges of studying SMCs should be met. Modern data acquisition methods allow for better analysis of soil microbial function and provide insight into agricultural practices that will yield increased food production in a sustainable manner.

Author Contributions

The first draft of the manuscript was written by GC; data collection and analysis were performed by MG and GM contributed to the revision. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

The authors declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontierspartnerships.org/articles/10.3389/sjss.2024.12080/full#supplementary-material

Abbreviations

SMCs, soil microbial communities; C, carbon; N, nitrogen; P, phosphorus; S, sulfur; SBCs, soil bacterial communities; GIS, Geographic Information Systems; SFC, soil fungal communities; PLFA, phospholipid fatty acid; AMF, arbuscular mycorrhizae fungi; ECM, ectomycorrhizal; DNA-rDNA, recombinant; RT, reduced tillage; CT, conventional tillage; DNA, deoxyribonucleic acid; PGPR, plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria; MG-RAST, metagenomic rapid annotations using subsystems technology; MEGAN, MEtaGenome Analyzer; RDP, Ribosomal Database Project; NGS, next-generation sequencing; BLAST, Basic Local Alignment Search Tool; RAPS, reduced alphabet-based protein similarity search; RTMg, Metagenomics project; QIIME, quantitative insights into microbial ecology.

Footnotes

1https://www.sciencedirect.com

2https://www.scopus.com/home.uri

6https://www.ingentaconnect.com

7https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com

References

Abbruzzini, T. F., Avitia, M., Carrasco-Espinosa, K., Peña, V., Barrón-Sandoval, A., Salazar Cabrera, U. I., et al. (2021). Precipitation Controls on Soil Biogeochemical and Microbial Community Composition in Rainfed Agricultural Systems in Tropical Drylands. Sustainability 13, 11848. doi:10.3390/su132111848

Akinola, S. A., Ayangbenro, A. S., and Babalola, O. O. (2021). Metagenomic Insight into the Community Structure of Maize-Rhizosphere Bacteria as Predicted by Different Environmental Factors and Their Functioning within Plant Proximity. Microorganisms 9 (7), 1419. doi:10.3390/microorganisms9071419

Alawiye, T. T., and Babalola, O. O. (2022). Metagenomic Insight into the Community Structure and Functional Genes in the Sunflower Rhizosphere Microbiome. Agriculture 11 (2), 167. doi:10.3390/agriculture11020167

Arif, I., Batool, M., and Schenk, P. M. (2020). Plant Microbiome Engineering: Expected Benefits for Improved Crop Growth and Resilience. Trends Biotechnol. 38, 1385–1396. doi:10.1016/j.tibtech.2020.04.015

Arumugam, T., Kinattinkara, S., Nambron, D., Velusamy, S., Shanmugamoorthy, M., Pradeep, T., et al. (2022). An Integration of Soil Characteristics by Using GIS Based Geostatistics and Multivariate Statistics Analysis Sultan Batheri Block, Wayanad District, India. Urban Clim. 46, 101339. doi:10.1016/j.uclim.2022.101339

Ashworth, A. J., DeBruyn, J. M., Allen, F. L., Radosevich, M., and Owens, P. (2017). Microbial Community Structure Is Affected by Cropping Sequences and Poultry Litter under Long-Term No-Tillage. Soil Biol. biochem. 114, 210–219. doi:10.1016/j.soilbio.2017.07.019

Banerjee, S., and van der Heijden, M. G. A. (2022). Soil Microbiomes and One Health. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 21 (1), 6–20. doi:10.1038/s41579-022-00779-w

Beatty, D. S., Aoki, L. R., Graham, O. J., and Yang, B. (2021). The Future Is Big-And Small: Remote Sensing Enables Cross-Scale Comparisons of Microbiome Dynamics and Ecological Consequences. mSystems 6 (6), e0110621. doi:10.1128/msystems.01106-21

Bergmann, G. T., Bates, S. T., Eilers, K. G., Lauber, C. L., Caporaso, J. G., Walters, W. A., et al. (2011). The Under-recognized Dominance of Verrucomicrobia in Soil Bacterial Communities. Soil Biol. biochem. 43 (7), 1450–1455. doi:10.1016/j.soilbio.2011.03.012

Boon, E., Meehan, C. J., Whidden, C., Wong, D. H. J., Langille, M. G., and Beiko, R. G. (2014). Interactions in the Microbiome: Communities of Organisms and Communities of Genes. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 38, 90–118. doi:10.1111/1574-6976.12035

Bowles, T. M., Acosta-Martínez, V., Calderón, F., and Jackson, L. E. (2014). Soil Enzyme Activities, Microbial Communities, and Carbon and Nitrogen Availability in Organic Agroecosystems across an Intensively-Managed Agricultural Landscape. Soil Biol. biochem. 68, 252–262. doi:10.1016/j.soilbio.2013.10.004

Buchfink, B., Xie, C., and Huson, D. H. (2015). Fast and Sensitive Protein Alignment Using DIAMOND. Nat. Methods. 12 (1), 59–60. doi:10.1038/nmeth.3176

Bünemann, E. K., Bongiorno, G., Bai, Z., Creamer, R. E., De Deyn, G., de Goede, R., et al. (2018). Soil Quality–A Critical Review. Soil Biol. biochem. 120, 105–125. doi:10.1016/j.soilbio.2018.01.030

Callahan, B. J., McMurdie, P. J., Rosen, M. J., Johnson, A. J. A., and Holmes, S. P. (2016). DADA2: High-Resolution Sample Inference from Illumina Amplicon Data. Nat. Methods. 13 (7), 581–583. doi:10.1038/nmeth.3869

Callahan, B. J., Wong, J., Heiner, C., Oh, S., Theriot, C. M., Gulati, A. S., et al. (2019). High-Throughput Amplicon Sequencing of the Full-Length 16S rRNA Gene with Single-Nucleotide Resolution. Nucleic Acids Res. 47 (18), e103. doi:10.1093/nar/gkz569

Cania, B., Vestergaard, G., Krauss, M., Fliessbach, A., Schloter, M., and Schulz, S. (2019). A Long-Term Field Experiment Demonstrates the Influence of Tillage on the Bacterial Potential to Produce Soil Structure-Stabilizing Agents Such as Exopolysaccharides and Lipopolysaccharides. Environ. Microbiomes. 14 (1), 1–4. doi:10.1186/s40793-019-0341-7

Cantarel, B. L., Coutinho, P. M., Rancurel, C., Bernard, T., Lombard, V., and Henrissat, B. (2009). The Carbohydrate-Active EnZymes Database (CAZy): An Expert Resource for Glycogenomics. Nucleic Acids Res. 37, D233–D238. doi:10.1093/nar/gkn663

Caporaso, J. G., Kuczynski, J., Stombaugh, J., Bittinger, K., Bushman, F. D., Costello, E. K., et al. (2010). QIIME Allows Analysis of High-Throughput Community Sequencing Data. Nat. Methods. 7, 335–336. doi:10.1038/nmeth.f.303

Carrara, J. E., Walter, C. A., Hawkins, J. S., Peterjohn, W. T., Averill, C., and Brzostek, E. R. (2018). Interactions Among Plants, Bacteria, and Fungi Reduce Extracellular Enzyme Activities under Long-Term N Fertilization. Glob. Chang. Biol. 24, 2721–2734. doi:10.1111/gcb.14081

Cascio, M., Morillas, L., Ochoa-Hueso, R., Delgado-Baquerizo, M., Munzi, S., Roales, J., et al. (2021). Nitrogen Deposition Effects on Soil Properties, Microbial Abundance, and Litter Decomposition Across Three Shrublands Ecosystems From the Mediterranean Basin. Front. Environ. Sci. 9, 709391. doi:10.3389/fenvs.2021.709391

Chaparro, J. M., Sheflin, A. M., Manter, D. K., and Vivanco, J. M. (2012). Manipulating the Soil Microbiome to Increase Soil Health and Plant Fertility. Biol. Fertil. Soils. 48, 489–499. doi:10.1007/s00374-012-0691-4

Cole, J. R., Chai, B., Marsh, T. L., Farris, R. J., Wang, Q., Kulam, S. A., et al. (2003). The Ribosomal Database Project (RDP-II): Previewing a New Autoaligner that Allows Regular Updates and the New Prokaryotic Taxonomy. Nucleic Acid. Res. 31, 442–443. doi:10.1093/nar/gkg039

Constancias, F., Terrat, S., Saby, N. P. A., Horrigue, W., Villerd, J., Guillemin, J., et al. (2015). Mapping and Determinism of Soil Microbial Community Distribution across an Agricultural Landscape. MicrobiologyOpen 4, 505–517. doi:10.1002/mbo3.255

Corrales, A., Turner, B. L., Tedersoo, L., Anslan, S., and Dalling, J. W. (2017). Nitrogen Addition Alters Ectomycorrhizal Fungal Communities and Soil Enzyme Activities in a Tropical Montane Forest. Fungal Ecol. 27, 14–23. doi:10.1016/j.funeco.2017.02.004

Cui, Y., Yong, L., Rongli, M., Wen, D., Zhixian, Z., and Xingming, H. (2020). Metagenomics Analysis of the Effects of Long-Term Stand Age on Beneficial Soil Bacterial Community Structure under Chinese Ancient Mulberry Farming Practice. Horti. Environ. Biotechnol. 61 (6), 1063–1071. doi:10.1007/s13580-020-00279-x

Davinic, M., Fultzm, L. M., Acosta-Martinez, V., Calderón, F. J., Cox, S. B., Dowd, S. E., et al. (2012). Pyrosequencing and Mid-Infrared Spectroscopy Reveal Distinct Aggregate Stratification of Soil Bacterial Communities and Organic Matter Composition. Soil Biol. biochem. 46, 63–72. doi:10.1016/j.soilbio.2011.11.012

Delgado-Baquerizo, M., Maestre, F. T., Reich, P. B., Jeffries, T. C., Gaitan, J. J., Encinar, D., et al. (2016). Microbial Diversity Drives Multifunctionality in Terrestrial Ecosystems. Nat. Commun. 7 (1), 10541–10548. doi:10.1038/ncomms10541

de Menezes, A., Clipson, N., and Doyle, E. (2012). Comparative Metatranscriptomics Reveals Widespread Community Responses During Phenanthrene Degradation in Soil. Environ. Microbiol. 14, 2577–2588. doi:10.1111/j.1462-2920.2012.02781.x

de Menezes, A. B., Prendergast-Miller, M. T., Poonpatana, P., Farrell, M., Bissett, A., Macdonald, L. M., et al. (2015). C/N Ratio Drives Soil Actinobacterial Cellobiohydrolase Gene Diversity. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 81, 3016–3028. doi:10.1128/aem.00067-15

Deng, X., Zhang, N., Shen, Z., Zhu, C., Liu, H., Xu, Z., et al. (2021). Soil Microbiome Manipulation Triggers Direct and Possible Indirect Suppression Against Ralstonia Solanacearum and Fusarium Oxysporum. NPJ Biofilms Microbiomes. 7(1), 1–10.

Dequiedt, S., Saby, N. P., Lelievre, M., Jolivet, C., Thioulouse, J., Toutain, B., et al. (2011). Biogeographical Patterns of Soil Molecular Microbial Biomass as Influenced by Soil Characteristics and Management. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 20, 641–652. doi:10.1111/j.1466-8238.2010.00628.x

Diaz-Gonzalez, F. A., Vuelvas, J., Correa, C. A., Vallejo, V. E., and Patino, D. (2022). Machine Learning and Remote Sensing Techniques Applied to Estimate Soil Indicators–Review. Ecol. Indic. 135, 108517. doi:10.1016/j.ecolind.2021.108517

Donn, S., Kirkegaard, J. A., Perera, G., Richardson, A. E., and Watt, M. (2015). Evolution of Bacterial Communities in the Wheat Crop Rhizosphere. Environ. Microbiol. 17, 610–621. doi:10.1111/1462-2920.12452

Du, X., Gu, S., Zhang, Z., Li, S., Zhou, Y., Zhang, Z., et al. (2023). Spatial Distribution Patterns across Multiple Microbial Taxonomic Groups. Environ. Res. 223, 115470. doi:10.1016/j.envres.2023.115470

Dubey, G., Kollah, B., Gour, V. K., Shukla, A. K., and Mohanty, S. R. (2016). Diversity of Bacteria and Archaea in the Rhizosphere of Bioenergy Crop Jatropha Curcas. 3 Biotech. 6 (2), 1–10. doi:10.1007/s13205-016-0546-z

Edgar, R. C. (2013). UPARSE: Highly Accurate OTU Sequences From Microbial Amplicon Reads. Nat. Methods. 10, 996–998. doi:10.1038/nmeth.2604

Edwards, J., Johnson, C., Santos-Medellin, C., Lurie, E., Podishetty, N. K., Bhatnagar, S., et al. (2015). Structure, Variation, and Assembly of the Root Associated Microbiomes of Rice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 112 (8), E911–E920. doi:10.1073/pnas.1414592112

Edwards, R. A., Olson, R., Disz, T., Pusch, G. D., Vonstein, V., Stevens, R., et al. (2012). Real Time Metagenomics: Using K-Mers to Annotate Metagenomes. Bioinformatics 28, 3316–3317. doi:10.1093/bioinformatics/bts599

Eisenhauer, N., Antunes, P. M., Bennett, A. E., Birkhofer, K., Bissett, A., Bowker, M. A., et al. (2017). Priorities for Research in Soil Ecology. Pedobiol. (Jena) 63, 1–7. doi:10.1016/j.pedobi.2017.05.003

Eren, A. M., Morrison, H. G., Lescault, P. J., Reveillaud, J., Vineis, J. H., and Sogin, M. L. (2015). Minimum Entropy Decomposition: Unsupervised Oligotyping for Sensitive Partitioning of High-Throughput Marker Gene Sequences. ISME J. 9 (4), 968–979. doi:10.1038/ismej.2014.195

Fan, K., Cardona, C., Li, Y., Shi, Y., Xiang, X., Shen, C., et al. (2017). Rhizosphere-Associated Bacterial Network Structure and Spatial Distribution Differ Significantly from Bulk Soil in Wheat Crop Fields. Soil Biol. biochem. 113, 275–284. doi:10.1016/j.soilbio.2017.06.020

Faoro, H., Alves, A. C., Souza, E. M., Rigo, L. U., Cruz, L. M., Al-Janabi, S. M., et al. (2010). Influence of Soil Characteristics on the Diversity of Bacteria in the Southern Brazilian Atlantic Forest. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 76, 4744–4749. doi:10.1128/AEM.03025-09

Farzadfar, S., Knight, J. D., and Congreves, K. A. (2021). Soil Organic Nitrogen: An Overlooked but Potentially Significant Contribution to Crop Nutrition. Plant Soil 462 (1), 7–23. doi:10.1007/s11104-021-04860-w

Fernandez, A. L., Sheaffer, C. C., Wyse, D. L., Staley, C., Gould, T. J., and Sadowsky, M. J. (2016). Associations between Soil Bacterial Community Structure and Nutrient Cycling Functions in Long-Term Organic Farm Soils Following Cover Crop and Organic Fertilizer Amendment. Sci. Total. Environ. 566, 949–959. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2016.05.073

Fierer, N., Leff, J. W., Adams, B. J., Nielsen, U. N., Bates, S. T., Lauber, C. L., et al. (2012). Cross-biome Metagenomic Analyses of Soil Microbial Communities and Their Functional Attributes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 109 (52), 21390–21395. doi:10.1073/pnas.1215210110

Finn, D., Kopittke, P. M., Dennis, P. G., and Dalal, R. C. (2017). Microbial Energy and Matter Transformation in Agricultural Soils. Soil Biol. biochem. 111, 176–192. doi:10.1016/j.soilbio.2017.04.010

Frey, B., Varliero, G., Qi, W., Stierli, B., Walthert, L., and Brunner, I. (2022). Shotgun Metagenomics of Deep Forest Soil Layers Show Evidence of Altered Microbial Genetic Potential for Biogeochemical Cycling. Front. Microbiol. 606, 828977. doi:10.3389/fmicb.2022.828977

Gao, M., Xiong, C., Gao, C., Tsui, C. K. M., Wang, M. M., Zhou, X., et al. (2021). Disease-Induced Changes in Plant Microbiome Assembly and Functional Adaptation. Microbiome 9 (1), 1–18. doi:10.1186/s40168-021-01138-2

Garcia, M. O., Templer, P. H., Sorensen, P. O., Sanders-DeMott, R., Groffman, P. M., and Bhatnagar, J. M. (2020). Soil Microbes Trade-Off Biogeochemical Cycling for Stress Tolerance Traits in Response to Year-Round Climate Change. Front. Microbiol. 11, 616. doi:10.3389/fmicb.2020.00616

Garibay-Valdez, E., Calderon, K., Vargas-Albores, F., Lago-Lestón, A., Martínez-Córdova, L. R., and Martínez-Porchas, M. (2020). Functional Metagenomics for Rhizospheric Soil in Agricultural Systems. Microb. Genom. Sustain. Agroeco. 1, 149–160. doi:10.1007/978-981-13-8739-5_8

Geisseler, D., and Scow, K. M. (2014). Long-Term Effects of Mineral Fertilizers on Soil Microorganisms–A Review. Soil Biol. biochem. 75, 54–63. doi:10.1016/j.soilbio.2014.03.023

Gholizadeh, S., Nemati, I., Vestergård, M., Barnes, C. J., Kudjordjie, E. N., and Nicolaisen, M. (2024). Harnessing Root-Soil-Microbiota Interactions for Drought-Resilient Cereals. Microbiol. Res. 283, 127698. doi:10.1016/j.micres.2024.127698

Goldfarb, K. C., Karaoz, U., Hanson, C. A., Santee, C. A., Bradford, M. A., Treseder, K. K., et al. (2011). Differential Growth Responses of Soil Bacterial Taxa to Carbon Substrates of Varying Chemical Recalcitrance. Front. Microbiol. 2, 94. doi:10.3389/fmicb.2011.00094

Graham, E. B., Knelman, J. E., Schindlbacher, A., Siciliano, S., Breulmann, M., Yannarell, A., et al. (2016). Microbes as Engines of Ecosystem Function: When Does Community Structure Enhance Predictions of Ecosystem Processes? Front. Microbiol. 7, 214. doi:10.3389/fmicb.2016.00214

Gu, S., Wei, Z., Shao, Z., Friman, V. P., Cao, K., Yang, T., et al. (2020). Competition for Iron Drives Phytopathogen Control by Natural Rhizosphere Microbiomes. Nat. Microbiol. 5 (8), 1002–1010. doi:10.1038/s41564-020-0719-8

Guan, P., Zhang, X., Yu, J., Cheng, Y., Li, Q., Andriuzzi, W. S., et al. (2018). Soil Microbial Food Web Channels Associated With Biological Soil Crusts in Desertification Restoration: The Carbon Flow From Microbes to Nematodes. Soil Biol. biochem. 116, 82–90. doi:10.1016/j.soilbio.2017.10.003

Gupta, V. V. S. R., and Germida, J. J. (2015). Soil Aggregation: Influence on Microbial Biomass and Implications for Biological Processes. Soil Biol. biochem. 80, A3–A9. doi:10.1016/j.soilbio.2014.09.002

Guseva, K., Darcy, S., Simon, E., Alteio, L. V., Montesinos-Navarro, A., and Kaiser, C. (2022). From Diversity to Complexity: Microbial Networks in Soils. Soil Biol. biochem. 169, 108604. doi:10.1016/j.soilbio.2022.108604

Haegeman, B., Hamelin, J., Moriarty, J., Neal, P., Dushoff, J., and Weitz, J. S. (2013). Robust Estimation of Microbial Diversity in Theory and in Practice. ISME J. 7 (6), 1092–1101. doi:10.1038/ismej.2013.10

Hartmann, M., Frey, B., Mayer, J., Mäder, P., and Widmer, F. (2015). Distinct Soil Microbial Diversity Under Long-Term Organic and Conventional Farming. ISME J. 9 (5), 1177–1194. doi:10.1038/ismej.2014.210

He, Z., Yuan, C., Chen, P., Rong, Z., Peng, T., Farooq, T. H., et al. (2023). Soil Microbial Community Composition and Diversity Analysis Under Different Land Use Patterns in Taojia River Basin. Forests 14 (5), 1004. doi:10.3390/f14051004

Helgason, B. L., Walley, F. L., and Germida, J. J. (2010). No-Till Soil Management Increases Microbial Biomass and Alters Community Profiles in Soil Aggregates. Appl. Soil Ecol. 46, 390–397. doi:10.1016/j.apsoil.2010.10.002

Herrera Paredes, S., and Lebeis, S. L. (2016). Giving Back to the Community: Microbial Mechanisms of Plant-Soil Interactions. Funct. Ecol. 30, 1043–1052. doi:10.1111/1365-2435.12684

Hu, X., Gu, H., Liu, J., Wei, D., Zhu, P., Zhou, B., et al. (2022). Metagenomics Reveals Divergent Functional Profiles of Soil Carbon and Nitrogen Cycling under Long-Term Addition of Chemical and Organic Fertilizers in the Black Soil Region. Geoderma 418, 115846. doi:10.1016/j.geoderma.2022.115846

Jackson, L. E., Bowles, T. M., Hodson, A. K., and Lazcano, C. (2012). Soil Microbial-Root and Microbial Rhizosphere Processes to Increase Nitrogen Availability and Retention in Agroecosystems. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 4, 517–522. doi:10.1016/j.cosust.2012.08.003

Kabir, A. H., Baki, M. Z. I., Ahmed, B., and Mostofa, M. G. (2024). Current, Faltering, and Future Strategies for Advancing Microbiome-Assisted Sustainable Agriculture and Environmental Resilience. New Crops (KeAi). 1, 100013. doi:10.1016/j.ncrops.2024.100013

Kalaimurugan, D., Sivasankar, P., Manikandan, E., Durairaj, K., Lavanya, K., Vasudhevan, P., et al. (2019). Spatial Determination of Soil Variables Using GIS Method and Their Influence on Microbial Communities in the Eastern Ghats Region. Trop. Ecol. 60, 16–29. doi:10.1007/s42965-019-00003-6

Keegan, K. P., Glass, E. M., and Meyer, F. (2016). MG-RAST, A Metagenomics Service for Analysis of Microbial Community Structure and Function. Micro. Environ. Geno 1399, 207–233. doi:10.1007/978-1-4939-3369-3_13

Kelly, C. N., Schwaner, G. W., Cumming, J. R., and Driscoll, T. P. (2021). Metagenomic Reconstruction of Nitrogen and Carbon Cycling Pathways in Forest Soil: Influence of Different Hardwood Tree Species. Soil Biol. biochem. 156, 108226. doi:10.1016/j.soilbio.2021.108226

Koeppel, A., Perry, E. B., Sikorski, J., Krizanc, D., Warner, A., Ward, D. M., et al. (2008). Identifying the Fundamental Units of Bacterial Diversity: A Paradigm Shift to Incorporate Ecology into Bacterial Systematics. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 105, 2504–2509. doi:10.1073/pnas.0712205105

Kurm, V., Visser, J., Schilder, M., Nijhuis, E., Postma, J., and Korthals, G. (2023). Soil Suppressiveness against Pythium Ultimum and Rhizoctonia solani in Two Land Management Systems and Eleven Soil Health Treatments. Microb. Ecol. 86, 1709–1724. doi:10.1007/s00248-023-02215-9

Lam, K. N., Cheng, J., Engel, K., Neufeld, J. D., and Charles, T. C. (2015). Current and Future Resources for Functional Metagenomics. Front. Microbiol. 6, 1196. doi:10.3389/fmicb.2015.01196

Lange, M., Eisenhauer, N., Sierra, C. A., Bessler, H., Engels, C., Griffiths, R. I., et al. (2015). Plant Diversity Increases Soil Microbial Activity and Soil Carbon Storage. Nat. Commun. 6 (1), 6707–6708. doi:10.1038/ncomms7707

Li, C., Liu, C., Li, H., Liao, H., Xu, L., Yao, M., et al. (2024a). The Microgeo: An R Package Rapidly Displays the Biogeography of Soil Microbial Community Traits on Maps. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 100 (7), fiae087. doi:10.1093/femsec/fiae087

Li, X., Chen, D., Carrión, V. J., Revillini, D., Yin, S., Dong, Y., et al. (2023b). Acidification Suppresses the Natural Capacity of Soil Microbiome to Fight Pathogenic Fusarium Infections. Nat. Commun. 14 (1), 5090. doi:10.1038/s41467-023-40810-z

Li, Y., Wang, C., Chang, H., Zhang, Y., Liu, S., and He, W. (2023a). Metagenomics Reveals the Effect of Long-Term Fertilization on Carbon Cycle in the Maize Rhizosphere. Front. Microbiol. 14, 1170214. doi:10.3389/fmicb.2023.1170214

Li, Z., Kravchenko, A. N., Cupples, A., Guber, A. K., Kuzyakov, Y., Philip Robertson, G., et al. (2024b). Composition and Metabolism of Microbial Communities in Soil Pores. Nat. Commun. 15 (1), 3578. doi:10.1038/s41467-024-47755-x

Liang, A., Zhang, Y., Zhang, X., Yang, X., McLaughlin, N., Chen, X., et al. (2019). Investigations of Relationships Among Aggregate Pore Structure, Microbial Biomass, and Soil Organic Carbon in a Mollisol Using Combined Non-Destructive Measurements and Phospholipid Fatty Acid Analysis. Soil Tillage Res. 185, 94–101. doi:10.1016/j.still.2018.09.003

Ligi, T., Oopkaup, K., Truu, M., Preem, J. K., Nõlvak, H., Mitsch, W. J., et al. (2014). Characterization of Bacterial Communities in Soil and Sediment of a Created Riverine Wetland Complex Using High-Throughput 16S rRNA Amplicon Sequencing. Ecol. Eng. 72, 56–66. doi:10.1016/j.ecoleng.2013.09.007

Lindgreen, S., Adair, K. L., and Gardner, P. P. (2015). An Evaluation of the Accuracy and Speed of Metagenome Analysis Tools. Sci. Rep. 6 (1), 19233. doi:10.1038/srep19233

Liu, L., Gundersen, P., Zhang, T., and Mo, J. (2012). Effects of Phosphorus Addition on Soil Microbial Biomass and Community Composition in Three Forest Types in Tropical China. Soil Biol. biochem. 44, 31–38. doi:10.1016/j.soilbio.2011.08.017

Liu, W., Yang, Z., Ye, Q., Peng, Z., Zhu, S., Chen, H., et al. (2023). Positive Effects of Organic Amendments on Soil Microbes and Their Functionality in Agro-Ecosystems. Plants 3790, 3790. doi:10.3390/plants12223790

Lori, M., Symnaczik, S., Mader, P., De Deyn, G., and Gattinger, A. (2017). Organic Farming Enhances Soil Microbial Abundance and Activity- A Meta-Analysis and Meta-Regression. PloS ONE 12 (7), e0180442. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0180442

Ma, B., Stirling, E., Liu, Y., Zhao, K., Zhou, J., Singh, B. K., et al. (2021) “Soil Biogeochemical Cycle Couplings Inferred From a Function-Taxon Network. Res. Wash D.C. 2021, 7102769. doi:10.34133/2021/7102769

Mamabolo, E., Pryke, J. S., and Gaigher, R. (2024). Soil Fauna Diversity Is Enhanced by Vegetation Complexity and No-Till Planting in Regenerative Agroecosystems. Agr. ecosys. Environ. 367, 108973. doi:10.1016/j.agee.2024.108973

Maron, P. A., Mougel, C., and Ranjard, L. (2011). Soil Microbial Diversity: Methodological Strategy, Spatial Overview and Functional Interest. C. R. Biol. 334 (5–6), 403–411. doi:10.1016/j.crvi.2010.12.003

Matsumoto, H., Fan, X., Wang, Y., Kusstatscher, P., Duan, J., Wu, S., et al. (2021). Bacterial Seed Endophyte Shapes Disease Resistance in Rice. Nat. Plants 7, 60–72. doi:10.1038/s41477-020-00826-5

Mayerhofer, J., Thuerig, B., Oberhaensli, T., Enderle, E., Lutz, S., Ahrens, C. H., et al. (2021). Indicative Bacterial Communities and Taxa of Disease-Suppressing and Growth-Promoting Composts and Their Associations to the Rhizoplane. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 97 (10), fiab134. doi:10.1093/femsec/fiab134

Mendes, L. W., Kuramae, E. E., Navarrete, A. A., van Veen, J. A., and Tsai, S. M. (2014). Taxonomical and Functional Microbial Community Selection in Soybean Rhizosphere. ISME J. 8, 1577–1587. doi:10.1038/ismej.2014.17

Mendes, R., Kruijt, M., de Bruijn, I., Dekkers, E., van der Voort, M., Schneider, J. H., et al. (2011). Deciphering the Rhizosphere Microbiome for Disease-Suppressive Bacteria. Science 332 (6033), 1097–1100. doi:10.1126/science.1203980

Mendoza, M. L., Sicheritz-Ponten, T., and Gilbert, M. T. (2015). Environmental Genes and Genomes: Understanding the Differences and Challenges in the Approaches and Software for Their Analyses. Brief. Bioinform 16, 745–758. doi:10.1093/bib/bbv001

Meng, S., Peng, T., Liu, X., Wang, H., Huang, T., Gu, J. D., et al. (2022). Ecological Role of Bacteria Involved in the Biogeochemical Cycles of Mangroves Based on Functional Genes Detected Through GeoChip 5.0. Msphere 7 (1), e0093621–21. doi:10.1128/msphere.00936-21

Meyer, F., Paarmann, D., D’Souza, M., Olson, R., Glass, E., Kubal, M., et al. (2008). The Metagenomics RAST Server– A Public Resource for the Automatic Phylogenetic and Functional Analysis of Metagenomes. BMC Bioinform 9 (1), 386–388. doi:10.1186/1471-2105-9-386

Mitra, S., Rupek, P., Richter, D. C., Urich, T., Gilbert, J. A., Meyer, F., et al. (2011). Functional Analysis of Metagenomes and Metatranscriptomes Using SEED and KEGG. BMC Bioinform 12 (1), S21–S28. doi:10.1186/1471-2105-12-s1-s21

Moeskops, B., Buchan, D., Van Beneden, S., Fievez, V., Sleutel, S., Gasper, M., et al. (2012). The Impact of Exogenous Organic Matter on SOM Contents and Microbial Soil Quality. Pedobiologia 55 (3), 175–184. doi:10.1016/j.pedobi.2012.03.001

Moulin, C., Pruneau, L., Vaillant, V., and Loranger-Merciris, G. (2023). Impacts of Agroecological Practices on Soil Microbial Communities in Experimental Open-Field Vegetable Cropping Systems. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 99 (4), fiad030. doi:10.1093/femsec/fiad030

Mummey, D., Holben, W., Six, J., and Stahl, P. (2006). Spatial Stratification of Soil Bacterial Populations in Aggregates of Diverse Soils. Micro. Ecol. 51, 404–411. doi:10.1007/s00248-006-9020-5

Nemergut, D. R., Schmidt, S. K., Fukami, T., O'Neill, S. P., Bilinski, T. M., Stanish, L. F., et al. (2013). Patterns and Processes of Microbial Community Assembly. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 77 (3), 342–356. doi:10.1128/mmbr.00051-12

Nisrina, L., Effendi, Y., and Pancoro, A. (2021). Revealing the Role of Plant Growth Promoting Rhizobacteria in Suppressive Soils against Fusarium Oxysporum F. Sp. Cubense Based on Metagenomic Analysis. Heliyon 7 (8), e07636. doi:10.1016/j.heliyon.2021.e07636

Ortiz-Estrada, Á. M., Gollas-Galván, T., Martínez-Córdova, L. R., and Martínez-Porchas, M. (2019). Predictive Functional Profiles Using Metagenomic 16S rRNA Data: A Novel Approach to Understanding the Microbial Ecology of Aquaculture Systems. Rev. Aquac. 11 (1), 234–245. doi:10.1111/raq.12237

Ossowicki, A., Tracanna, V., Petrus, M. L., van Wezel, G., Raaijmakers, J. M., Medema, M. H., et al. (2020). Microbial and Volatile Profiling of Soils Suppressive to Fusarium Culmorum of Wheat. Proc. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 287 (1921), 20192527. doi:10.1098/rspb.2019.2527

Ounit, R., Wanamaker, S., Close, T. J., and Lonardi, S. (2015). CLARK: Fast and Accurate Classification of Metagenomic and Genomic Sequences Using Discriminative K-Mers. BMC Genom 16 (1), 1–13. doi:10.1186/s12864-015-1419-2

Paliy, O., and Shankar, V. (2016). Application of Multivariate Statistical Techniques in Microbial Ecology. Mol. Ecol. 25 (5), 1032–1057. doi:10.1111/mec.13536

Pasternak, Z., Al-Ashhab, A., Gatica, J., Gafny, R., Avraham, S., Minz, D., et al. (2013). Spatial and Temporal Biogeography of Soil Microbial Communities in Arid and Semiarid Regions. PLoS One 8, e69705. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0069705

Pathan, M., Keerthikumar, S., Ang, C. S., Gangoda, L., Quek, C. Y., Williamson, N. A., et al. (2015). FunRich: An Open Access Standalone Functional Enrichment and Interaction Network Analysis Tool. Proteomics 15 (15), 2597–2601. doi:10.1002/pmic.201400515

Peralta, A. L., Sun, Y., McDaniel, M. D., and Lennon, J. T. (2018). Crop Rotational Diversity Increases Disease Suppressive Capacity of Soil Microbiomes. Ecosphere 9 (5). doi:10.1002/ecs2.2235

Ranjard, L., Dequiedt, S., Chemidlin Prévost-Bouré, N., Thioulouse, J., Saby, N., Lelievre, M., et al. (2013). Turnover of Soil Bacterial Diversity Driven by Wide-Scale Environmental Heterogeneity. Nat. Commun. 4 (1), 1434. doi:10.1038/ncomms2431

Rillig, M. C., Ryo, M., Lehmann, A., Aguilar-Trigueros, C. A., Buchert, S., Wulf, A., et al. (2019). The Role of Multiple Global Change Factors in Driving Soil Functions and Microbial Biodiversity. Science 366 (6465), 886–890. doi:10.1126/science.aay2832

Ruamps, L. S., Nunan, N., and Chenu, C. (2011). Microbial Biogeography at the Soil Pore Scale. Soil Biol. biochem. 43 (2), 280–286. doi:10.1016/j.soilbio.2010.10.010

Ruamps, L. S., Nunan, N., Pouteau, V., Leloup, J., Raynaud, X., Roy, V., et al. (2013). Regulation of Soil Organic C Mineralisation at the Pore Scale. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 86 (1), 26–35. doi:10.1111/1574-6941.12078

Sanad, H., Moussadek, R., Mouhir, L., Oueld Lhaj, M., Dakak, H., El Azhari, H., et al. (2024). Assessment of Soil Spatial Variability in Agricultural Ecosystems Using Multivariate Analysis, Soil Quality Index (SQI), and Geostatistical Approach: A Case Study of the Mnasra Region, Gharb Plain, Morocco. Agronomy 14, 1112. doi:10.3390/agronomy14061112

Schloss, P. D., Westcott, S. L., Ryabin, T., Hall, J. R., Hartmann, M., Hollister, E. B., et al. (2009). Introducing Mothur: Open-Source, Platform-independent, Community-Supported Software for Describing and Comparing Microbial Communities. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 75 (23), 7537–7541. doi:10.1128/aem.01541-09

Schmidt, T. S., Matias Rodrigues, J. F., and von Mering, C. (2014). Ecological Consistency of SSU rRNA-Based Operational Taxonomic Units at a Global Scale. PLoS Comput. Biol. 10 (4), e1003594. doi:10.1371/journal.pcbi.1003594

Shade, A. (2023). Microbiome Rescue: Directing Resilience of Environmental Microbial Communities. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 72, 102263. doi:10.1016/j.mib.2022.102263

Shen, C., Xiong, J., Zhang, H., Feng, Y., Lin, X., Li, X., et al. (2013). Soil pH Drives the Spatial Distribution of Bacterial Communities along Elevation on Changbai Mountain. Soil Biol. biochem. 57, 204–211. doi:10.1016/j.soilbio.2012.07.013

Silva, G. G. Z., Cuevas, D. A., Dutilh, B. E., and Edwards, R. A. (2014). FOCUS: An Alignment-free Model to Identify Organisms in Metagenomes Using Non-negative Least Squares. Peer J. 2, e425. doi:10.7717/peerj.425

Silva, G. G. Z., Green, K. T., Dutilh, B. E., and Edwards, R. A. (2016). SUPER-FOCUS: A Tool for Agile Functional Analysis of Shotgun Metagenomic Data. Bioinformatics 32 (3), 354–361. doi:10.1093/bioinformatics/btv584

Singh, B. K., Trivedi, P., Egidi, E., Macdonald, C. A., and Delgado-Baquerizo, M. (2020). Crop Microbiome and Sustainable Agriculture. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 18 (11), 601–602. doi:10.1038/s41579-020-00446-y

Szoboszlay, M., and Tebbe, C. C. (2021). Hidden Heterogeneity and Co-occurrence Networks of Soil Prokaryotic Communities Revealed at the Scale of Individual Soil Aggregates. Microbiologyopen 10 (1), e1144. doi:10.1002/mbo3.1144

Thébault, A., Clément, J. C., Ibanez, S., Roy, J., Geremia, R. A., Pérez, C. A., et al. (2014). Nitrogen Limitation and Microbial Diversity at the Treeline. Oikos 123, 729–740. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0706.2013.00860.x

Thilagavathi, R., Nakkeeran, S., Balachandar, D., Raguchander, T., and Samiyappan, R. (2021). Bacterial Community Analysis on Sclerotium-Suppressive Soil. Arch. Microbiol. 203 (7), 4539–4548. doi:10.1007/s00203-021-02426-z

Tracanna, V., Ossowicki, A., Petrus, M. L., Overduin, S., Terlouw, B. R., Lund, G., et al. (2021). Dissecting Disease-Suppressive Rhizosphere Microbiomes by Functional Amplicon Sequencing and 10× Metagenomics. MSystems 6 (3), e0111620. doi:10.1128/msystems.01116-20

Trivedi, P., Rochester, I. J., Trivedi, C., Van Nostrand, J. D., Zhou, J., Karunaratne, S., et al. (2016). Soil Aggregate Size Mediates the Impacts of Cropping Regimes on Soil Carbon and Microbial Communities. Soil Biol. biochem. 91, 169–181. doi:10.1016/j.soilbio.2015.08.034

Truong, D. T., Franzosa, E. A., Tickle, T. L., Scholz, M., Weingart, G., Pasolli, E., et al. (2015). MetaPhlAn2 for Enhanced Metagenomic Taxonomic Profiling. Nat. methods. 12 (10), 902–903. doi:10.1038/nmeth.3589

Turner, S., Mikutta, R., Meyer-Stüve, S., Guggenberger, G., Schaarschmidt, F., Lazar, C. S., et al. (2017). Microbial Community Dynamics in Soil Depth Profiles over 120,000 Years of Ecosystem Development. Front. Microbiol. 8, 874. doi:10.3389/fmicb.2017.00874

van der Heijden, M. G., Martin, F. M., Selosse, M. A., and Sanders, I. R. (2015). Mycorrhizal Ecology and Evolution: The Past, the Present, and the Future. New Phytol. 205 (4), 1406–1423. doi:10.1111/nph.13288

Vanwonterghem, I., Jensen, P. D., Ho, D. P., Batstone, D. J., and Tyson, G. W. (2014). Linking Microbial Community Structure, Interactions and Function in Anaerobic Digesters Using New Molecular Techniques. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 27, 55–64. doi:10.1016/j.copbio.2013.11.004

Venter, Z. S., Jacobs, K., and Hawkins, H. J. (2016). The Impact of Crop Rotation on Soil Microbial Diversity: A Meta-Analysis. Pedobiologia 59 (4), 215–223. doi:10.1016/j.pedobi.2016.04.001

Wang, L., Gan, Y., Bainard, L. D., Hamel, C., St-Arnaud, M., and Hijri, M. (2020). Expression of N-Cycling Genes of Root Microbiomes Provides Insights for Sustaining Oilseed Crop Production. Environ. Microbiol. 22, 4545–4556. doi:10.1111/1462-2920.15161

Wang, Y., Liu, Z., Hao, X., Wang, Z., Wang, Z., Liu, S., et al. (2023). Biodiversity of the Beneficial Soil-Borne Fungi Steered by Trichoderma-Amended Biofertilizers Stimulates Plant Production. NPJ Biofilms Microbiomes 9 (1), 46. doi:10.1038/s41522-023-00416-1

Waring, B. G., Averill, C., and Hawkes, C. V. (2013). “Differences in Fungal and Bacterial Physiology Alter Soil Carbon and Nitrogen Cycling: Insights from Meta-Analysis and Theoretical Models. Ecol. Lett. 16, 887–894. doi:10.1111/ele.12125

Weedon, J. T., Kowalchuk, G. A., Aerts, R., Freriks, S., Röling, W. F. M., and van Bodegom, P. M. (2017). Compositional Stability of the Bacterial Community in a Climate-Sensitive Sub-arctic Peatland. Front. Microbiol. 8, 317. doi:10.3389/fmicb.2017.00317

Wei, X., Xie, B., Wan, C., Song, R., Zhong, W., Xin, S., et al. (2024). Enhancing Soil Health and Plant Growth through Microbial Fertilizers: Mechanisms, Benefits, and Sustainable Agricultural Practices. Agronomy 14 (3), 609. doi:10.3390/agronomy14030609

Wood, D. E., and Salzberg, S. L. (2014). Kraken: Ultrafast Metagenomic Sequence Classification Using Exact Alignments. Genome Biol. 15, R46. doi:10.1186/gb-2014-15-3-r46

Wood, S. A., Almaraz, M., Bradford, M. A., McGuire, K. L., Naeem, S., Neill, C., et al. (2015). Farm Management, Not Soil Microbial Diversity, Controls Nutrient Loss From Smallholder Tropical Agriculture. Front. Microbiol. 6, 90. doi:10.3389/fmicb.2015.00090

Wu, H., Cui, H., Fu, C., Li, R., Qi, F., Liu, Z., et al. (2024). Unveiling the Crucial Role of Soil Microorganisms in Carbon Cycling: A Review. Sci. Total Environ. 909, 168627. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2023.168627

Wu, X., Peng, J., Liu, P., Bei, Q., Rensing, C., Li, Y., et al. (2021). Metagenomic Insights into Nitrogen and Phosphorus Cycling at the Soil Aggregate Scale Driven by Organic Material Amendments. Sci. Tot. Environ. 785, 147329. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.147329

Xiong, C., and Lu, Y. (2022). Microbiomes in Agroecosystem: Diversity, Function and Assembly Mechanisms. Environ. Microbiol. Rep. 14 (6), 833–849. doi:10.1111/1758-2229.13126

Xu, L., Dong, Z., Chiniquy, D., Pierroz, G., Deng, S., Gao, C., et al. (2021a). Genome-Resolved Metagenomics Reveals Role of Iron Metabolism in Drought-Induced Rhizosphere Microbiome Dynamics. Nat. Commun. 12 (1), 3209. doi:10.1038/s41467-021-23553-7

Xu, L., Pierroz, G., Wipf, H. M., Gao, C., Taylor, J. W., Lemaux, P. G., et al. (2021b). Holo-Omics for Deciphering Plant-Microbiome Interactions. Microbiome 9, 69. doi:10.1186/s40168-021-01014-z

Xu, X., Thornton, P. E., and Post, W. M. (2013). A Global Analysis of Soil Microbial Biomass Carbon, Nitrogen and Phosphorus in Terrestrial Ecosystems. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 22 (6), 737–749. doi:10.1111/geb.12029

Yu, J., Deem, L. M., Crow, S. E., Deenik, J., and Penton, C. R. (2019). Comparative Metagenomics Reveals Enhanced Nutrient Cycling Potential After 2 Years of Biochar Amendment in a Tropical Oxisol. App. Environ. Microbiol. 85 (11), e02957–18. doi:10.1128/aem.02957-18