- 1Departamento Académico de Ciencias Agropecuarias, Universidad Nacional de San Agustín de Arequipa, Arequipa, Peru

- 2Grupo de Edafología y Tecnologías del Medio Ambiente · GETECMA, Department of Agrochemistry and Environment, University Miguel Hernández, Alicante, Spain

Fire is a natural ecological force, but its effects vary significantly depending on the ecosystem. While fire-adapted ecosystems, such as Mediterranean woodlands, recover quickly, non-fire adapted regions like the Peruvian Andes are highly vulnerable to soil degradation, especially with increasing wildfire frequency and intensity due to climate change. The study investigates the effects of a 2018 wildfire in the Pichu Pichu volcano mountain area, a shrubland ecosystem at 3,700 m a.s.l. The arid conditions and unique soil characteristics, such as the Torripsamment soil on volcaniclastic sandstones, make the area particularly vulnerable to fire-induced degradation. Soils were evaluated three and 4 years after the fire event under two key dominant plant species in the ecosystem: Berberis lutea and Parastrephia quadrangularis. The results show that the combined fire and post-fire erosion processes significantly impacted soil properties, leading to a loss of soil organic carbon (SOC), increased bulk density (BD), loss of soil structure and, in the second sampling, a strong reduction in clay content attributable to weak aggregation and erosive processes. Soils under Berberis exhibited greater SOC losses, likely due to its larger biomass that intensified the combustion effects. The decrease in SOC resulted in soil compaction. Water repellency (WR), a natural feature in these soils due to the high sand content, remained largely unaffected by the fire. However, the persistence of WR may hinder water infiltration, increasing surface runoff and erosion, especially in the absence of vegetation post-fire. The findings highlight the fragility of these Andean soils to fire events, contrasting with the resilience that Mediterranean ecosystems often display. This lack of recovery underscores the need for improved wildfire prevention and post-fire soil management strategies, particularly as climate change further exacerbates the risks of soil degradation due to reduced water availability and more frequent fires in these fragile arid ecosystems.

Introduction

Fire is a natural ecological factor that has shaped landscapes for millennia, both through natural process but also human activity; however, not all ecosystems are equally adapted to the fire effects (McLauchlan et al., 2020; Sánchez-García et al., 2024). Fire-adapted ecosystems, such as Mediterranean woodlands, savannas, and some grasslands, have evolved specific traits like fire-resistant bark, serotinous cones, or rapid resprouting ability of vegetation species, allowing them to resist and recover quickly from fire disturbances (Bond and Keeley, 2005). In contrast, arid and semi-arid regions lack these natural fire adaptations mechanisms, making them particularly vulnerable to degradation when exposed to frequent or intense fire events (Pausas and Keeley, 2009). In recent decades, fire weather seasons have extended, and extreme fire weather conditions have become more common on a global scale (Jones et al., 2022). This increase in fire activity is expanding into regions historically characterized by infrequent fire occurrences, including arid ecosystems with limited fuel productivity (Bedia et al., 2015; Kolden et al., 2024). These shifts raise concerns about the potential impacts of novel fire regimes, especially the resilience of these more fragile, arid landscapes that remain less studied compared to fire-prone ecosystems. While the response of plant communities to fire in arid ecosystems has been extensively studied, the impacts on soil physical, chemical, and biological properties remain significantly underexplored (Muñoz-Rojas et al., 2016). Global reviews of fire effects consistently highlight the underrepresentation of South America studies, particularly in arid ecosystems (Giorgis et al., 2021; Souza-Alonso et al., 2022). The review by Giorgis et al. (2021) identified arid ecosystems as the most severely affected by fire in South America, with significant impacts in bulk density and organic matter loss. Despite these findings, research in these ecosystems remains scarce, with most existing research focusing on plant responses rather than soil processes.

Wildfires in the Peruvian Andes, particularly in arid and semi-arid regions, have become an increasing concern due to their escalating ecological and socio-economic impacts. Although fire is not a frequent natural disturbance in the Andes, ignitions due to human activities—such as agricultural burning, land clearing, and grazing practices—combined with drier and warmer conditions due to climate change, have intensified fire occurrence in recent decades (Armenteras et al., 2020). The consequences of these wildfires are severe, especially for the fragile highland ecosystems known as páramos and puna, which are poorly adapted to fire and are at high risk of degradation. According to Hardesty et al. (2005), the shrubland area in this study region is classified as fire-independent, meaning that these ecosystems did not evolve with frequent fires. As a result, the vegetation and ecological processes in these areas do not have specific adaptative mechanisms required to recover from fire disturbances. This context makes fire management and prevention strategies a critical priority for conserving these unique ecosystems and protecting the livelihoods of local communities (IPCC, 2021). According to official data on registered fires in Peru in recent years, the number has been increasing exponentially. The annual average of fires from 2003 to 2012 was 37.2, which rose to 127.6 during the 2013-2017 period. However, the surge in recent years has been particularly alarming: 248 fires were recorded in 2018, 675 in 2019, and 1,039 in 2020 (Source: INCEDI, published in CENEPRED, 2020).

In arid zones like Arequipa, wildfires exacerbate the region’s existing challenges of limited water availability, leading to further soil degradation. Moreover, the destruction of native vegetation in these areas directly threatens biodiversity and can have long-lasting effects on ecosystem resilience, water regulation, and carbon storage (Zhang et al., 2023).

Fire significantly impacts soils by altering their physical, chemical, and biological properties. The effects of fire vary based on factors such as intensity, duration, frequency, and the specific characteristics of the soil and vegetation involved (Doerr et al., 2023). Fires can disrupt soil aggregation in case of a loss of organic matter essential for binding soil particles together, and increase compaction, hindering water and air penetration, but these effects are also controlled by the soil type and characteristics (Mataix-Solera et al., 2011). While fires release nutrients locked in plant biomass, thereby increasing short-term nutrient availability, high-intensity fires may result in nutrient depletion due to leaching and volatilization (Certini, 2005). The combustion of organic matter reduces soil organic carbon, which is critical for soil health, and can negatively affect microbial communities, altering their composition and activity (Bárcenas-Moreno et al., 2011). Additionally, fires can create water-repellent layers in the soil, particularly in sandy soils, leading to increased surface runoff and erosion (Doerr et al., 2000). After a wildfire, the soil surface becomes exposed due to the absence or reduction of vegetation cover (Bowker et al., 2008), making it highly vulnerable to rainfall events, runoff, and erosion processes (Johansen et al., 2001). The loss of vegetation leaves the soil unprotected, increasing the risk of surface degradation, especially in regions prone to intense rainfall or unstable soil conditions. Overall, the effects of fire on soil are complex and can have both immediate and long-term consequences for ecosystem health, emphasizing the need for effective land management and recovery strategies in an era of increasing fire frequency and severity (Abatzoglou and Williams, 2016). Certain physical properties, such as soil aggregation and water repellency, are particularly important for assessing a soil’s vulnerability and condition regarding degradation following a wildfire (Mataix-Solera et al., 2021). These characteristics provide critical insights into how fire impacts soil health and its ability to recover from disturbances.

Given the rising frequency of wildfires in the arid and semi-arid regions, there is still limited understanding of how these ecosystems respond to fire events. The scarcity of research, particularly in the remote areas of the Andean region, highlights a gap in knowledge that urge for studies focused on understanding the ecosystem’s resilience to these increasing disturbances. This knowledge is essential for formulating effective strategies to mitigate wildfire impacts and facilitate recovery in affected regions. This study aims to address this gap by investigating the impacts of wildfire on soil physical and chemical properties in the Peruvian Andes. Our hypothesis is that the fire events have significant negative effects on key soil parameters, slowing post-fire recovery and increasing soil vulnerability under arid conditions. By studying the role of dominant plant species in influencing these effects, this study wants to provide insights into the mid-term effects of wildfires on soil health and ecosystem resilience, contributing with valuable information for future fire management and conservation strategies in these fragile ecosystems.

Material and Methods

Study Area, Fieldwork and Soil Sampling

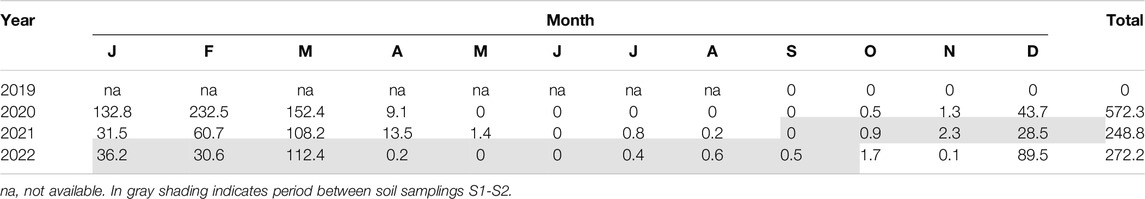

The study was conducted in the Pichu Pichu volcano mountain, at 3,700 m a.s.l. in the Arequipa region of Perú (Figure 1). The area is characterized by a varied topography, with mountainous formations and small inter-Andean valleys. The climate is classified as cold desert (BWk) according to the Köppen-Geiger classification (Kottek et al., 2006). In Arequipa, the mean annual precipitation is 96.5 mm, and the mean annual temperature is 10°C, ranging from 4°C to 18°C. However, at the altitude of the study area, the precipitation increases compared to lower altitudes, averaging 385 mm annually, mainly concentrated in three-four months without rain during the rest of the year, supporting the existence of a shrubland landscape of high ecological value. Soils are developed over volcaniclastic sandstones and classify as Torripsamment (Soil Survey Staff, 2014).

Figure 1. Location of study area and sampling points. BB, Burned under Berberis, BP, Burned under Parastrephia; CB, Control under Berberis; CP, Control under Parastrephia.

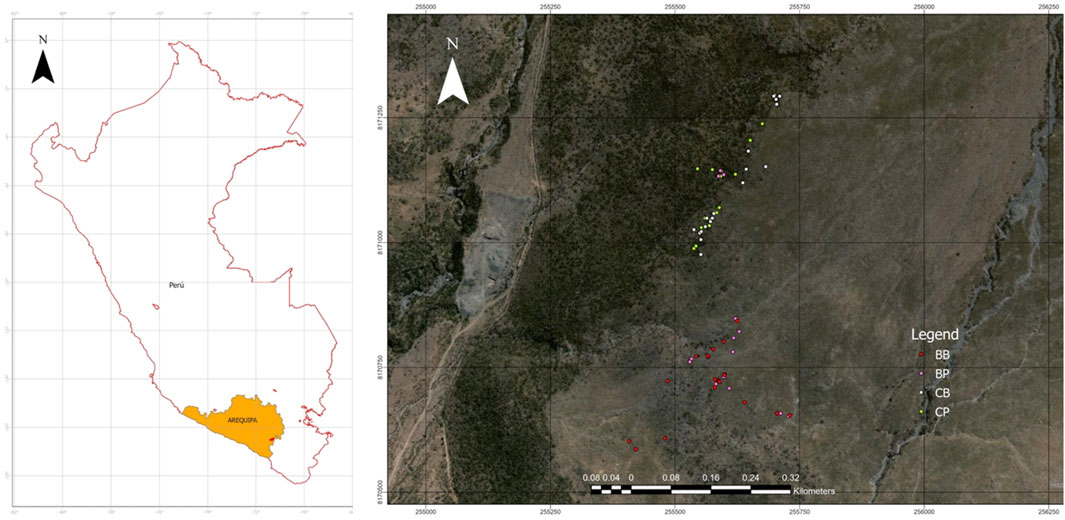

The ecosystem is a desert shrub type, dominated by shrubs less than 4 m high and xerophytic species, and fragile areas susceptible to desertification (Figure 2). The vegetation is composed of shrub communities of both deciduous and evergreen nature, showing notable floristic diversity. The most representative families are Asteraceae and Cactaceae. The dominant species include the shrubby Berberis lutea, Parastrephia quadrangularis (Thola), and the herbaceous Jaraba ichu (Ichu). Other less dominant species present are Chuquiraga spinosa and Adesmia spinossissima. At these altitudes, some low-growing and dispersed tree species can also be found, such as Cantua buxifolia and Berberis lutea.

Figure 2. Representative images of the study area. (A) Scrubland landscape. (B) image of Polylepis forest (dark vegetation) taken from fire-affected area; (C) Berberis lutea; (D) Parastrephia quadrangularis; (E) Individual of Berberis lutea burned; (F) image of first centimetres sampled of the Loamy sand soil. Image credits: (A, B, E, F): Jorge Mataix-Solera, (C): Tatiana Salazar, (D): Lunsden Coaguila.

For this study, Berberis lutea and Parastrephia quadrangularis were specifically selected due to their high ecological importance in this fragile ecosystem. Their survival strategies under extreme arid conditions, such as leaves that end in thorns in Berberis lutea to reduce water loss, or the unique growth form of Parastrephia quadrangularis as an invested crescent or truncated cone that enhance and regulate soil water absorption, make them of significant relevance for the ecosystem. These species provide important ecosystem services, including habitat for endemic species, flood prevention, and erosion control. Given that Arequipa is immersed in the coastal desert of Atacama, one of the driest deserts on the planet, the influence of these species on soil properties under new fire regimes is key for understanding the ecosystem resilience.

Between 4th and 6th September 2018, a wildfire burned an area of 1992 ha, affecting a scrubland landscape of high ecological value in the Pichu Pichu volcano mountain. Fire severity was classified as moderate to high according to Keeley (2009). Understory plants were charred or consumed, fine dead twigs on soil surface were consumed and log charred, and grey ash covered the soil. Desert shrub species in this area, such as Parastrephia quadrangularis, Chuquirraga rotundifolia, and Adesmia spinossissima, are not adapted to fire and were burned down to the roots. This fire did not reach the nearby Polylepis forest, whose characteristic bark formed by papyraceous ritidoma can increase the available fuel for fire spread.

With the aim of knowing the status of soil after the fire and its evolution over time, two soil samplings were carried out in September 2021 and September 2022, corresponding to 3 and 4 years after the fire, respectively. At each sampling, 40 soil samples were collected from the first 5 cm depth of mineral soils, 20 from burned areas and 20 from unburned areas. Samples were taken under the two representative plant species, Berberis lutea and Parastrephia quadrangularis, which differ in size and therefore in their potential contribution as fuel to the fire and their impact on soils during their combustion. Each sample was collected beneath individual plants after removing any litter or ash present. A cylinder measuring 5 cm in diameter and 5 cm in height was then used to collect the sample.

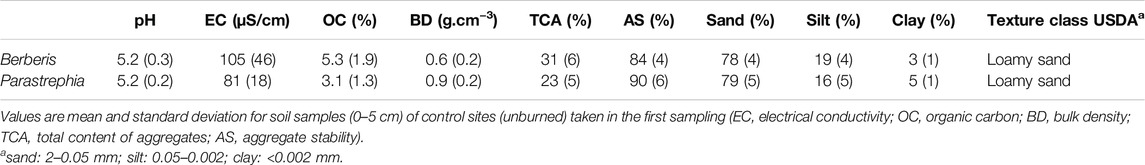

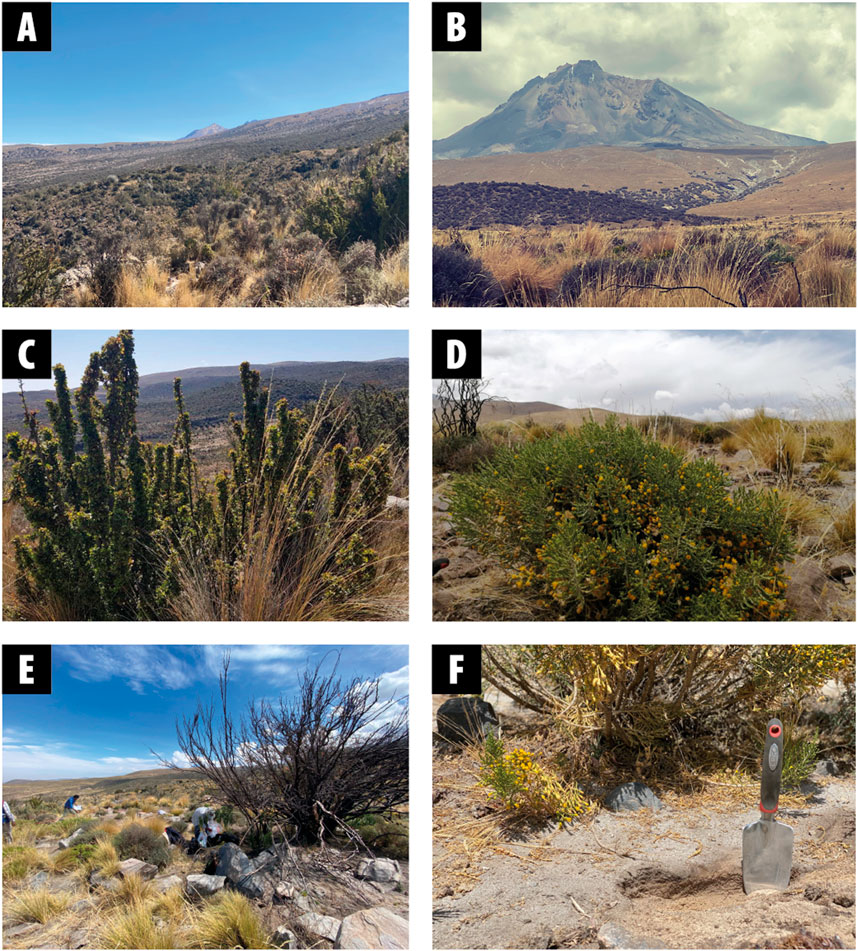

As a first characterization of the soils under the two selected plant species, the pH is acid, with low values of electrical conductivity, and has a Loamy sand texture with very low values of clay. This results in very low content of aggregates but high stability of those existing, probably because good values of organic matter and hydrophobicity (Mataix-Solera and Doerr, 2004). The organic carbon content is higher in soils under Berberis while the bulk density is lower compared to areas dominated by Parastrephia (Table 1).

The irregular and intense rainfall pattern was crucial for understanding the soil response after the fire disturbance in the study area. Rainfall data were obtained from the nearest meteorological station, located 6 km from the study area at a similar altitude, with records available from September 2019 (Table 2). Annual rainfall in this region is highly variable, a characteristic typical of arid areas, with pronounced interannual fluctuations. For example, the total rainfall in 2020 (572.3 mm) was more than double that of the following 2 years (248.8 mm in 2021 and 272.2 mm in 2022). Extreme events were marked by high intensity, such as 36 mm falling in just 2 h on 17 February2020. Focusing on the period between the two soil sampling events (S1 and S2, indicated by shade gray in Table 2), a total of 213.4 mm of rain was recorded. Remarkably, 97% of this precipitation occurred over just 4 months, with 53% concentrated in a single month (March). Moreover, this rainfall was unevenly distributed across only 6 days, with 30 mm falling in just 4 h on 12 March 2022.

Field and Laboratory Analysis

Under laboratory conditions, various soil properties were analysed: pH, electrical conductivity (EC), soil texture, water repellency (WR), organic matter content (OM), aggregation [including total content of macroaggregates (TCA; the percentage of the sample forming macroaggregates) and their stability (AS; the percentage of macroaggregates that withstand a simulated rainfall of known energy)], and bulk density (BD). Soil pH and electrical conductivity were measured in a 1:2.5 and a 1:5 (w/v) aqueous extract, respectively. Soil texture was determined using the Bouyoucos method (Gee and Bauder, 1986). Organic carbon (OC) content was measured by the Walkley and Black method (Nelson and Sommers, 1982). The water drop penetration time (WDPT) test (Wessel, 1988) was employed to assess WR persistence. Before WR measurement, approximately 15 g of each soil sample was placed on plastic dishes and exposed in a chamber to a controlled laboratory environment conditions (20°C, ∼50% relative humidity) for 1 week to mitigate any effects of previous atmospheric humidity variations on soil WR (Doerr et al., 2005). This involved placing three drops of distilled water (∼0.05 mL) on the sample surface and recording the time required for full penetration. The average time for the triplicate drops was recorded as the WDPT value of the sample, then classified based on Bisdom et al. (1993) and Doerr et al. (1998) as follows: wettable (<5 s), slightly water repellent (5–60 s), strongly water repellent (60–600 s), severely water repellent (600–3,600 s), and extremely water repellent (>3,600 s). Soil aggregate stability (AS) and total content of macroaggregates (TCA) were studied within the macroaggregate fraction of 4–0.25 mm, determined using the rainfall simulator method according to Roldán et al. (1994) and based on Benito and Díaz-Fierros (1989). This method assesses the proportion of macroaggregates that remain intact after the soil sample undergoes artificial rainfall of a specific energy, and also allows for the calculation of the proportion of the sample forming macroaggregates by weight differences (TCA). More detailed information of this method is described in Mataix-Solera et al. (2021). Bulk density was measured using undisturbed soil cores of 100 cm3.

Close to the same places where each soil samples were collected measurements of hydraulic conductivity (K) were made by using a Mini-Disk Infiltrometer (MDI) (Decagon Devices, 2018; Robichaud et al., 2008). The volume of water infiltrated was recorded every 30 s and at least for 10 min.

Statistical Procedures

All statistical analyses were performed using RStudio version (2023) (RStudio Team, 2023). The effects of fire occurrence, plant species, and time since the fire on soil properties were assessed using a PERMANOVA analysis with the adonis2 function in vegan with 999 permutations, followed by a visual representation of such factors in sample ordination using Bray-Curtis distance in a Non-Metric Multidimensional Scaling (NMDS) plot. Soil properties were analyzed individually using ANOVA models. When normality assumptions were not met for water repellency (WR) and hydraulic conductivity (K), data were log-transformed to achieve a normal distribution of errors, with back-transformed values presented for K to aid interpretation. Multiple comparisons among fire occurrence and plant species were performed with Tukey’s post hoc tests. Pearson correlation coefficients (r) were calculated to quantify the linear relationship between soil parameters under study. In addition, a Principal Component Analysis (PCA) was performed on all soil samples to explore the relationships between measured soil parameters and fire occurrence and time since fire for each plant species using the “FactoMineR” package implemented in R (Le et al., 2008).

Results

The PERMANOVA analysis shows significant effects of the studied factors on soil properties (Table 3). A strong effect of plant species was detected (p < 0.001), indicating that both Berberis and Parastrephia significantly influenced the soil properties over time and regardless of fire occurrence. These strong differences are visually observed in an ordination plot (Supplementary Figure S1), where species are consistently clustered separately across fire conditions and time. In addition to the species effect, fire occurrence had a significant effect on soil properties when comparing burned and control soils, together with the time significant effect (Table 3). The three-way interaction between species, fire, and time showed a moderate significance suggesting a combined influence of these factors on soil properties.

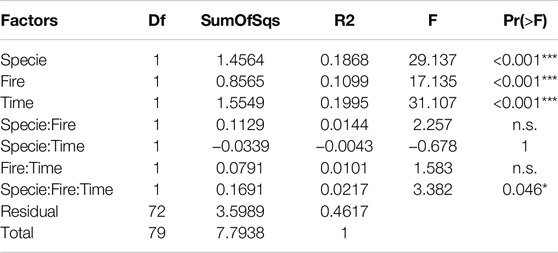

Table 3. PERMANOVA results showing the effects of species (Berberis lutea and Parastrephia quadrangularis), fire occurrence (burned and controls), and time (S1 and S2), and interactions between them (significant codes: p < 0.001, “***”; p < 0.01, “**”; p < 0.05, “*”).

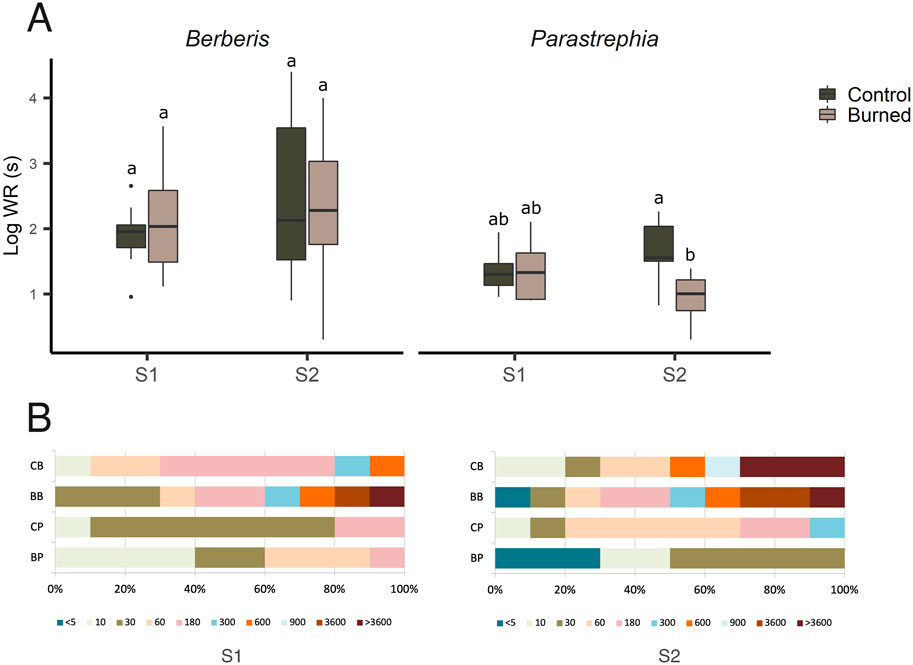

Analysing the soil properties individually, the water repellency (WR) observed in these soils was not driven by the fire occurrence but is a natural characteristic caused by the high sand content (Table 1) and elevated SOC in the topsoil. The lower specific surface area of sand particles makes them more easily coated by hydrophobic organic compounds. In S1, 100% of the samples showed WR in both control and burned plots, without statistical differences in log-transformed values (WR) (Figure 3A). However, burned soils under Berberis showed higher variability of repellency classes, with more frequency of samples showing extreme WR classes (Figure 3B). Soils under Parastrephia had lower values of WR compared to Berberis, although all samples in S1 exhibited WR. In these soils 1 year later (S2), WR statistically decreased in burned soils (p = 0.006**), showing a significant fire-time interaction (p = 0.011*; Supplementary Table S1; Figure 5). The most extreme classes of WR in S2 were observed in soils under Berberis, with some samples classified in WR class >3,600 s. However, some burned samples became hydrophilic, 10% and 30% for Berberis and Parastrephia, respectively (Figure 3B).

Figure 3. (A) Box-plots of soil water repellency, expressed as Log (WDPT) (s), per plant species comparing burned soils vs. controls and for the two soil samplings (S1 and S2). Different letters mean significant differences at p > 0.05, and (B) Frequency of distribution in WDPT classes (s); CB, Control under Berberis; BB, Burned under Berberis; CP, Control under Parastrephia; BP, Burned under Parastrephia; for S1 (left) and S2 (right).

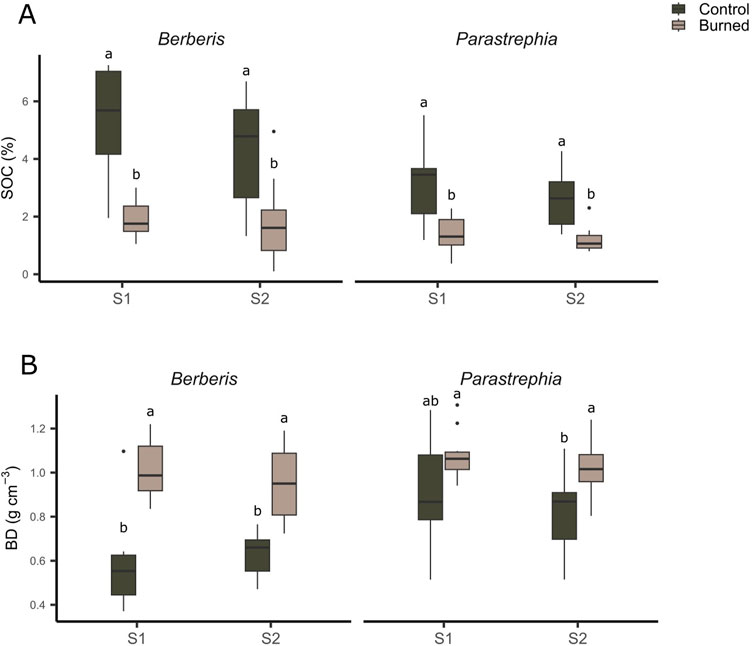

A significant decrease in soil organic carbon (SOC) in the first 5 cm of mineral soil was observed 3 years after the wildfire (S1) for both plant species. The reduction was more pronounced under Berberis (from 5.3% to 1.9%) compared to Parastrephia (from 3.1% to 1.4%) (Figure 4A). These differences remained significant in S2.

Figure 4. Box-plots of (A) soil organic carbon (%) and (B) bulk density (g cm−3) per plant species comparing burned soils vs. controls and for the two soil samplings (S1 and S2). Different letters mean significant differences at p < 0.05.

The loss of SOC was reflected in the increase in bulk density (BD) (Figure 4B), indicating a soil compaction in burned soils that persists over time (same results in S1 and S2, three and 4 years after the wildfire). The higher differences between control and burned soils were observed for Berberis. Negative correlations between SOC and BD were confirmed in bi-correlations for all pooled data (r = −0.74, p < 0.001), and for each plant species individually (Supplementary Table S2).

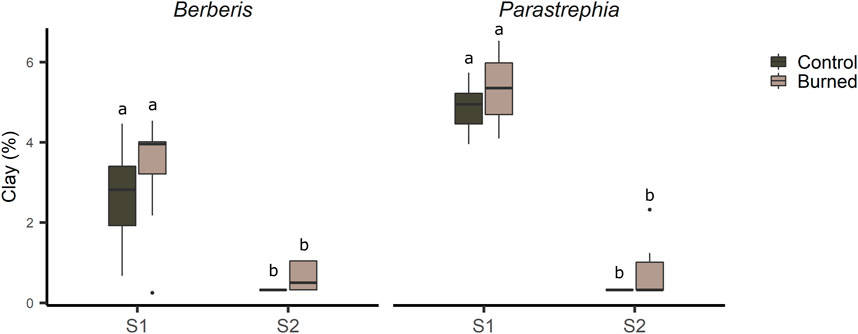

The natural clay content of soils is low at less than 6% (control soils at S1, Table 1), showing no significant differences between burned and control soils at S1. However, a significant decline was detected 4 years after the fire (S2) for both plant species (Figure 5), with also a moderately significant effect of the fire occurrence factor in Parastrephia soils (Supplementary Table S1). This loss of clay was reflected in the decrease of aggregate stability (AS) (Figure 6B), with both parameters showing a positive and significant correlation (r = 0.72, p < 0.001), also for both plant species (Supplementary Table S2).

Figure 5. Box-plots of Clay content (%) per plant species comparing burned soils vs. controls and for the two soil samplings (S1 and S2). Different letters mean significant differences at p < 0.05.

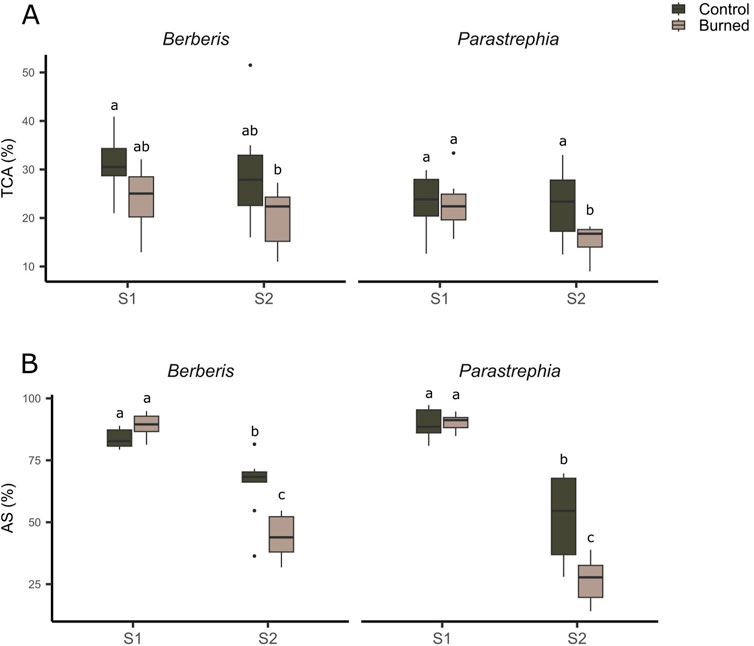

Figure 6. Box-plots of (A) Total content of aggregates (TCA) (%) and (B) Aggregate Stability (AS) (%) per plant species comparing burned soils vs. controls and for the two soil samplings (S1 and S2). Different letters mean significant differences at p < 0.05.

In terms of soil structure parameters, the proportion of samples forming macro-aggregates (TCA) was low, with mean values in control soils of 30% and 23% for Berberis and Parastrephia, respectively. Burned soil samples tended to show lower TCA values, decreasing over time for both plant species. The decrease was statistically significant in Parastrephia soils in S2, with market differences from the control soil. Similarly, in burned soils under Berberis, TCA was also significantly lower in S2 compared to control soils at the beginning of the study (Figure 6A).

Aggregate stability (AS) was initially high in S1, exceeding 80% in both burned and control soils, with no significant effect of fire occurrence for both plants’ species (Figure 6B). However, a marked decrease was observed between soil samplings, with statistically significant differences of time (p < 0.001***) for both species. In S2, the fire occurrence impacted the AS values, with significantly lower values in burned soils compared to control soils, dropping to below 50% for Berberis and near 25% for Parastrephia (Figure 6B).

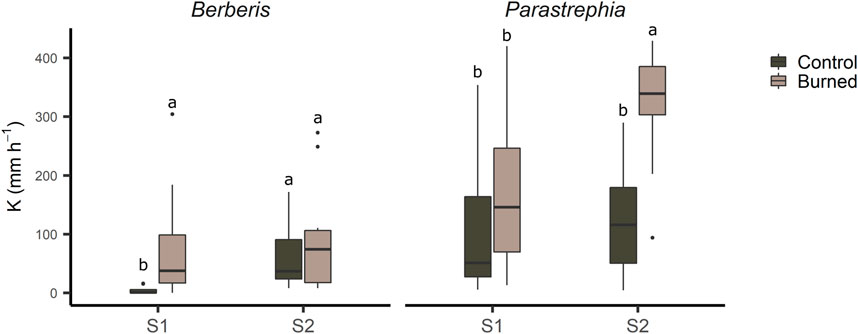

In S1, field measurements of hydraulic conductivity (K) in control soils were low under Berberis, with a trend to increase in burned soils. One year later (S2), a significant increase was observed under Parastrephia in burned soils (Figure 7). These results align with the patterns observed for WR, where the lower WR values were found for burned soils under Parastrephia (Figure 3A). A significant negative correlation between K and WR parameters for this species was confirmed (Supplementary Table S2).

Figure 7. Box-plots of Hydraulic conductivity, K (mm h−1) per plant species comparing burned soils vs. controls and for the two soil samplings (S1 and S2). Different letters mean significant differences at p < 0.05.

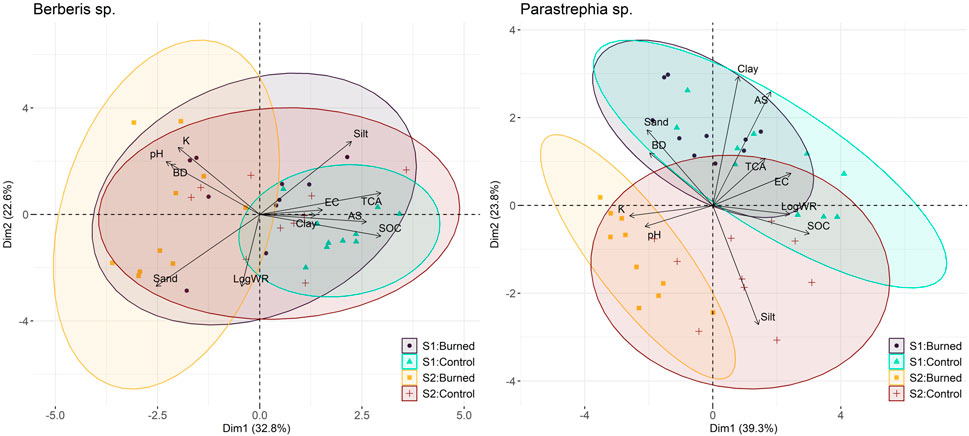

Given the significant differences between species observed in both the PERMANOVA analysis (Table 3) and the individual soil properties, we conducted species-specific multivariate analyses to better understand these variations. The principal component analyses (PCA) for both Berberis and Parastrephia species visually confirm the trends observed in the soil parameters affected by fire and time (Figure 8). For both species, the strongest separation was observed between the control soils at S1 and burned soils at S2, highlighting the significant impact of time and fire occurrence on the whole set of soil properties, consistent with the PERMANOVA findings. In the case of Parastrephia, control and burned soils clustered together at S1, suggesting minimal differences due to the fire at this time point, but greater differentiation became significant in the following sampling (S2).

Figure 8. Scores and loadings for PCA performed with results of all soil samples per plant species. AS, aggregate stability; SOC, soil organic carbon content; TCA, total content of macroaggregates; WR, water repellency; BD, Bulk density; EC, Electrical conductivity.

Burned soils at S2 were positioned on the left part of the plots, largely explained by increased values of K and pH, with BD also contributing to this group in Berberis soils. In the opposite direction, control soils at S1 were explained by higher values of TCA, AS, clay content, and SOC. In Parastrephia, SOC clustered apart together with WR in a separate quadrant, suggesting a unique relationship between these parameters for this species.

Discussion

This study provides clear evidence of degradation processes following the wildfire in the Andean region, that could be driven by both direct combustion effects and indirect post-fire erosive processes (Doerr et al., 2023; Shakesby and Doerr, 2006). Both plant species, Berberis lutea and Parastrephia quadrangularis, evidenced a distinct role in influencing soil degradation after the wildfire, with the larger biomass of Berberis probably contributing to more pronounced combustion effects on soils. The loss of soil organic carbon (SOC) emerges as the key trigger in the decline of soil resilience, which is not only reduced through the direct effects of combustion but also through post-fire erosion processes. Continuous strong erosive events, such as those occurred during study period, further intensify the degradation of the highly susceptible soils affected by a wildfire. The vulnerability of the Andean soils to fire resides in their inherent characteristics, which includes a loamy sand texture with more than 75% of sand and very low content of clay (less than 5%), natural presence of water repellency and low level of aggregation. These factors, combined with the loss of protective plant cover, makes soils very susceptible to the degradative process following wildfires (Mataix-Solera et al., 2021).

A key finding of this study is that soil water repellency (WR), naturally occurring in the Andean soils studied, remained unaffected by the wildfire three and 4 years later. The loamy sand texture, the elevated organic matter content, and acid pH make these soils prone to the natural development of WR (Doerr et al., 2000), although the persistence over time can be highly variable. Previous studies under laboratory heating conditions reveal that minor variations in soil properties, such as texture, clay fraction mineralogy, and the quantity and quality of organic matter, can influence the development and persistence of WR, with sand content being one of the most significant factors controlling the expression of this property (Mataix-Solera et al., 2014; Negri et al., 2024). In our case, the high sand content is probably the main driver of soil hydrophobicity, since the lower specific surface area allows hydrophobic substances to cover them more easily, making sandy soils the most susceptible to WR development (González-Peñaloza et al., 2013).

The natural development of WR is highly relevant to ecosystem-scale hydrological processes, particularly in arid environments. In fact, several studies have proposed that the natural occurrence of WR induced by plants may serve as a competitive strategy, aiding species to conserve water by directing water into deeper soil layers (e.g., Scott, 1992; Moore and Blackwell, 1998) and minimizing surface evaporation (Doerr et al., 2000). However, its persistence becomes problematic during the period between the fire event and the vegetation recovery, as exposed soils become more vulnerable to erosion due to increased runoff rates (Shakesby and Doerr, 2006). Fires can either induce WR in previously wettable soils or eliminate it in originally water-repellent soils, depending on factors such as the temperature reached in soils during the fire (DeBano, 2000). Our results show no significant changes in WR 3 years after the fire, only minimal differences 4 years post-fire for Parastrephia, probably linked to the slight reduction in SOC content. Therefore, although the fire was of moderate severity for vegetation, it may have not reached the necessary soil temperatures (200°C–400°C) to destroy WR, as the heat exposure was probably insufficient to permanently eliminate this property in this type of soil (Arcenegui et al., 2007; Negri et al., 2024).

The low resilience of Andean soils to fires was demonstrated by the strong and persistent decrease in SOC over time. Fire intensity and severity are responsible for the magnitude of the direct loss of soil organic matter (Keeley, 2009), which mainly depends on the vegetation burning process in forest and shrubland ecosystems. The burning of larger amounts of biomass under Berberis compared to Parastrephia probably contributed to the greater SOC loss observed in these soils. However, the strong decline in SOC cannot explain solely due to combustion; post-fire erosion processes may significantly contribute to soil loss during the first years post-fire given that not significant differences in WR were found between burned and control soils. Rainfall events in this arid region are limited to just a few days per year, but the bare soil conditions make these events highly soil erosive. The differences remained 1 year later (S2), with no signs of recovery on soil properties, different as the observed in most of Mediterranean semiarid soils affected by fires (Añó Vidal et al., 2022), emphasizing the fragility of Andean soils.

A critical consequence of the SOC reduction was the soil compaction, evidenced by the increase in bulk density (BD). This compaction was pronounced under Berberis, likely due to the initially higher SOC content associated with higher litter inputs (Table 1). Organic matter generates binding agents in soils, reducing its susceptibility to compaction by lowering the maximum bulk density (Blanco-Canqui et al., 2013). The decline in SOC, coupled with the BD increase, reduce the soil’s water storage capacity, with major implications for arid ecosystems. The substantial BD increase and its potential consequences in the hydrological processes further highlight the vulnerability of these soils to SOC loss, demonstrating the reduced soil resilience following fire and post-fire erosion events.

The low clay content in these soils further limits their water storage capacity, making them largely reliant on organic matter for structure. The detected loss of clay content between samplings, attributable to erosion processes, appears to be one of the main causes of soil structural loss. Its reduction had a significant impact on aggregate stability (AS) and total content of aggregates (TCA) in S1, being this last one already low before the fire event. The effects of fires on soil aggregation vary depending on the primary binding agents in the soil, as documented by Mataix-Solera et al. (2011). In soils where organic matter is the main binding agent -typically found in younger, sand-rich soils- a aggregation loss is more pronounced. In contrast, in soils containing higher amounts of clay, carbonates, and iron or aluminium oxides, which act as cementing agents, fire can lead to either increased aggregate stability or minimal change (Negri et al., 2024).

The lower resilience of Andean soils to wildfires compared to fire-prone ecosystems is revealed in the persistent loss of structural aggregation. Recently, Negri et al. (2024), through controlled laboratory heating experiments, compared soils from various biomes worldwide and found that acidic soils from cold, wet climates with low clay content were significantly prone to develop extreme water repellency and to loss aggregate stability. In contrast, soils from Mediterranean, tropical forest, and savannah biomes showed different responses, as aggregation in these regions is primarily driven by iron oxyhydroxides and clay rather than organic matter. Their study clearly highlighted the vulnerability of specific biomes to thermal-induced soil degradation. Similar results were observed in the young soils of Torres del Paine in Chilean Patagonia, which were impacted by a large wildfire in 2012 (Mataix-Solera et al., 2021). In our case in Arequipa, all factors except wet climate conditions, contribute to the development of water repellency, which indicate our soil is highly vulnerable to the loss of particle aggregation. The arid conditions result in a slow recovery after fire, leaving the soil exposed to erosion processes for an extended period due to prolonged bare soil exposure.

Hydraulic conductivity (K) serves as critical indication of soil function, with especial relevance for arid environments. The property is primarily influenced by soil porosity, which is determined by soil texture and structure, as well as the presence and persistence of water repellency (Miyata et al., 2007). Although the loamy sand texture of these soils would typically promote higher K, the poor soil structure (TCA and AS) and the presence of water repellency lower its effectiveness in enhancing water infiltration in soils. K values were relatively low, but slight changes in WR seems to influence hydraulic conductivity, as observed for Parastrephia with the negative and significant correlation between these two parameters.

The different responses of soils under Berberis and Parastrephia highlight their different roles in influencing post-fire soil resilience and degradation. After a wildfire, the species showed distinct effects on soils, particularly in terms of SOC, BD, and WR, with the larger specie- Berberis- showing the most severe and persistent impacts on soils. Given their dominance in this ecosystem, the effects on soil properties may have broader landscape-scale implications, suggesting to negative consequences for water storage capacity, a critical factor for this arid environment.

Vegetation plays a vital role in protecting these fragile soils from erosive processes and enhancing soil stability. This is particularly critical due to the low percentage of macroaggregates and the presence of water repellency, which further compromises soil cohesion. After a fire, these areas become highly vulnerable, especially because the arid conditions prolong the period during which the soil is exposed to erosion. Unlike more humid environments or regions adapted to fire, such as Mediterranean ecosystems, these soils lack natural resilience, making them more susceptible to degradation in the post-fire recovery phase (Shakesby and Doerr, 2006). In this context, implementing post-fire conservation practices is crucial for mitigating the impact of future fires in such environments. One of the most effective strategies for controlling soil erosion in fire-affected areas is mulching (Girona-García et al., 2021); however, it is essential to carefully select the mulching material to avoid introducing external seeds that could disrupt the ecological restoration process. Additionally, these measures must be tailored to the local social and economic context to ensure their feasibility and effectiveness. The study by Souza-Alonso et al. (2022) provides a valuable framework for guiding post-fire restoration decisions. Nevertheless, further research is necessary to address the specific challenges of arid environments, where fires are becoming increasingly common.

Conclusion

This study revealed significant and persistent soil degradation three and 4 years after a wildfire in the Peruvian Andes region of Arequipa, with no evidence of recovery in key soil properties such as soil organic carbon and bulk density. Our findings demonstrate that indicators like soil aggregation and water repellency are valuable for assessing the vulnerability of these young, fire-affected soils. Additionally, the observed post-fire erosion processes further highlight the fragility of this arid soils in response to wildfire events.

This research provides new scientific insights by demonstrating that Peruvian Andean soils, compared to fire adapted ecosystems, show low resilience to fire events, making them more susceptible to long-term degradation. The results highlight the importance of intensifying wildfire prevention efforts and prioritizing post-fire soil protection measures by wildlife conservation agencies to safeguard these fragile and valuable ecosystems. However, further research in these arid ecosystems is essential to better understand the mid- and long-term effects of fire in arid ecosystems, to better assess their recovery over time.

Given the current climate change scenario, where projections indicate an increased frequency of extreme events such wildfires and reduced water availability in arid ecosystems in South America (IPCC, 2021; Jones et al., 2024), the vulnerability of these ecosystems is expected to escalate. This study highlights the need to address the combined risks of wildfires and climate change in this fragile region of Peruvian Andes.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Author Contributions

LC funding acquisition to conduct the study, conceived and designed research, conducted the fieldwork, collected data, supervised analyses and wrote the manuscript. JM-S also participated in the funding acquisition, design of the research, fieldwork and wrote the manuscript. SN participated in the fieldwork, collected data and laboratory analysis. MG-C did the statistical analysis, performed the figures and tables and wrote the manuscript. ES fieldwork and acquisition of data. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This work was supported by funding from the Program “UNSA RESEARCH” of the Vicerrectorate of investigation of the UNSA, through the Project of ref: IBA-IB-65-2020-UNSA, and with the help of “POSTFIRE_CARE” project of the Spanish Research Agency (AEI) and the European Union through European Funding for Regional Development (FEDER) (Ref.: CGL2016-75178-C2-1-R).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI Statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their gratitude to the “Comunidad Campesina Polobaya” and “Comunidad Campesina Pocsi” for granting access to the research areas. Special thanks are also extended to the SERFOR (Servicio Forestal y de Fauna Silvestre) administration in Arequipa, particularly to Ing. Felipe Gonzales Dueñas, for their valuable support.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontierspartnerships.org/articles/10.3389/sjss.2025.13983/full#supplementary-material

References

Abatzoglou, J. T., and Williams, A. P. (2016). Impact of Anthropogenic Climate Change on Wildfire Across Western US Forests. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 113 (42), 11770–11775. doi:10.1073/pnas.1607171113

Añó Vidal, C., Sánchez Díaz, J., and Carbó Valverde, E. (2022). Efectos de Los Incendios en Los Suelos Forestales de la Comunidad Valenciana. Revisión Bibliográfica. Cuaternario Geomorfol. 36 (1-2), 53–75. doi:10.17735/cyg.v36i1-2.92407

Arcenegui, A., Mataix-Solera, J., Guerrero, C., Zornoza, R., Mayoral, A. M., and Morales, J. (2007). Factors Controlling the Water Repellency Induced by Fire in Calcareous Mediterranean Forest Soils. Eur. J. Soil Sci. 58, 1254–1259. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2389.2007.00917.x

Armenteras, D., González, T. M., Vargas Ríos, O., Meza Elizalde, M. C., and Oliveras, I. (2020). Incendios en Ecosistemas del Norte de Suramérica: Avances en la Ecología del Fuego Tropical en Colombia, Ecuador y Perú. Caldasia 42 (1), 1–16. doi:10.15446/caldasia.v42n1.77353

Bárcenas-Moreno, G., García-Orenes, F., Mataix-Solera, J., Mataix-Beneyto, J., and Bååth, E. (2011). Soil Microbial Recolonisation After a Fire in a Mediterranean Forest. Biol. Fertil. Soils 47, 261–272. doi:10.1007/s00374-010-0532-2

Bedia, J., Herrera, S., Gutiérrez, J. M., Benali, A., Brands, S., Mota, B., et al. (2015). Global Patterns in the Sensitivity of Burned Area to Fire-Weather: Implications for Climate Change. Agr. For. Meteorol. 214, 369–379. doi:10.1016/j.agrformet.2015.09.002

Benito, E., and Díaz-Fierros, F. (1989). Estudio de los Principales Factores que Intervienen en la Estabilidad Estructural de los Suelos de Galicia. Anal. Edafol. Agrobiol. 48, 229–253.

Bisdom, E. B. A., Dekker, L. W., and Schoute, J. F. T. (1993). Water Repellency of Sieve Fractions From Sandy Soils and Relationships With Organic Material and Soil Structure. Geoderma 56, 105–118. doi:10.1016/0016-7061(93)90103-R

Blanco-Canqui, H., Shapiro, C. A., Wortmann, C. A., Drijber, R. A., Mamo, M., Shaver, T. M., et al. (2013). Soil Organic Carbon: The Value to Soil Properties. J. Soil Water Conserv. 68 (5), 129A–134A. doi:10.2489/jswc.68.5.129A

Bond, W. J., and Keeley, J. E. (2005). Fire as a Global 'Herbivore': The Ecology and Evolution of Flammable Ecosystems. Trends Ecol. Evol. 20 (7), 387–394. doi:10.1016/j.tree.2005.04.025

Bowker, M. A., Belnap, J., Chaudhary, V. B., and Johnson, N. C. (2008). Revisiting Classic Water Erosion Models in Drylands: The Strong Impact of Biological Soil Crusts. Soil Biol. biochem. 40 (9), 2309–2316. doi:10.1016/j.soilbio.2008.05.008

CENEPRED (2020). “Escenario de Riesgo por Incendios Forestales,” in Informe Elaborado por el Centro Nacional de Estimación, Prevención y Reducción del Riesgo de Desastres. Available at: www.cenepred.gob.pe.

Certini, G. (2005). Effects of Fire on Properties of Forest Soils: A Review. Oecologia 143 (1), 1–10. doi:10.1007/s00442-004-1788-8

DeBano, L. F. (2000). The Role of Fire and Soil Heating on Water Repellency in Wildland Environments: A Review. J. Hydrol. 231–232, 195–206. doi:10.1016/S0022-1694(00)00194-3

Doerr, S. H., Douglas, P., Evans, R. C., Morley, C. P., Mullinger, N. J., Bryant, R., et al. (2005). Effects of Heating and Post-Heating Equilibration Times on Soil Water Repellency. Soil Res. 43, 261–267. doi:10.1071/SR04092

Doerr, S. H., Santín, C., and Mataix-Solera, J. (2023). “Fire Effects on Soil,“ in Encyclopedia of Soils in the Environment. 2nd edn. Vol. 2, 448–457. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-822974-3.00106-3

Doerr, S. H., Shakesby, R. A., and Walsh, R. P. D. (1998). Spatial Variability of Soil Hydrophobicity in Fire-Prone Eucalyptus and Pine Forests, Portugal. Soil Sci. 163, 313–324. doi:10.1097/00010694-199804000-00006

Doerr, S. H., Shakesby, R. A., and Walsh, R. P. D. (2000). Soil Water Repellency: Its Causes, Characteristics and Hydro-Geomorphological Significance. Earth-Sci. Rev. 51 (1-4), 33–65. doi:10.1016/s0012-8252(00)00011-8

Gee, G. W., and Bauder, J. W. (1986). “Particle-Size Analysis,” in Methods of Soil Analysis 1: Physical and Mineralogical Methods. Editor A. Klute 2nd ed. (Madison, WI: Am. Soc. Agron. Madison), 383–411.

Giorgis, M. A., Zeballos, S. R., Carbone, L., Zimmermann, H., von Wehrden, H., Aguilar, R., et al. (2021). A Review of Fire Effects Across South American Ecosystems: The Role of Climate and Time Since Fire. Fire Ecol. 17, 11–20. doi:10.1186/s42408-021-00100-9

Girona-García, A., Vieira, D. C. S., Silva, J., Fernández, C., Robichaud, P. R., and Keizer, J. J. (2021). Effectiveness of Post-Fire Soil Erosion Mitigation Treatments: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Earth-Sci. Rev. 217, 103611. doi:10.1016/J.EARSCIREV.2021.103611

González-Peñaloza, F. A., Zavala, L. M., Jordán, A., Bellinfante, N., Bárcenas-Moreno, G., Mataix-Solera, J., et al. (2013). Water Repellency as Conditioned by Particle Size and Drying in Hydrophobized Sand. Geoderma 209–210, 31–40. doi:10.1016/j.geoderma.2013.05.022

Hardesty, J., Myers, R., and Fulks, W. (2005). Fire, Ecosystems and People: A Preliminary Assessment of Fire as a Global Conservation Is-Sue. George Wright Forum 22 (4), 78–86.

IPCC. (2021). Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report.

Johansen, M. P., Hakonson, T. E., and Breshears, D. D. (2001). Post-fire runoff and erosion from rainfall simulation: contrasting forests with shrublands and grasslands. Hydrol. Proc. 15 (15), 2953–2965. doi:10.1002/hyp.384

Jones, M. W., Abatzoglou, J. T., Veraverbeke, S., Andela, N., Lasslop, G., Forkel, M., et al. (2022). Global and Regional Trends and Drivers of Fire under Climate Change. Rev. Geophys. 60 (3), e2020RG000726. doi:10.1029/2020rg000726

Jones, M. W., Kelley, D. I., Burton, C. A., Di Giuseppe, F., Barbosa, M. L. F., Brambleby, E., et al. (2024). State of Wildfires 2023–2024. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 16 (8), 3601–3685. doi:10.5194/essd-16-3601-2024

Keeley, J. E. (2009). Fire Intensity, Fire Severity and Burn Severity: A Brief Review and Suggested Usage. Int. J. Wildland Fire 18, 116–126. doi:10.1071/WF07049

Kolden, C. A., Abatzoglou, J. T., Jones, M. W., and Jain, P. (2024). Wildfires in 2023. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 5 (4), 238–240. doi:10.1038/s43017-024-00544-y

Kottek, M., Grieser, J., Beck, C., Rudolf, B., and Rubel, F. (2006). World Map of the Koppen-Geiger Climate Classification Updated. Meteorol. Zeitschr. 15 (3), 259–263. doi:10.1127/0941-2948/2006/0130

Le, S., Josse, J., and Husson, F. (2008). FactoMineR: An R Package for Multivariate Analysis. J. Stat. Soft. 25, 1–18. doi:10.18637/jss.v025.i01

Mataix-Solera, J., Arcenegui, V., Zavala, L. M., Pérez-Bejarano, A., Jordán, A., Morugán-Coronado, A., et al. (2014). Small Variations of Soil Properties Control Fire-Induced Water Repellency. Span. J. Soil Sci. 4, 51–60. doi:10.3232/SJSS.2014.V4.N1.03

Mataix-Solera, J., Arellano, E. C., Jaña, J. E., Olivares, L., Guardiola, J., Arcenegui, V., et al. (2021). Soil Vulnerability Indicators to Degradation by Wildfires in Torres del Paine National Park (Patagonia, Chile). Span. J. Soil Sci. 11, 10008. doi:10.3389/sjss.2021.10008

Mataix-Solera, J., Cerdà, A., Arcenegui, V., Jordán, A., and Zavala, L. M. (2011). Fire Effects on Soil Aggregation: A Review. Earth Sci. Rev. 109, 44–60. doi:10.1016/j.earscirev.2011.08.002

Mataix-Solera, J., and Doerr, S. H. (2004). Hydrophobicity and Aggregate Stability in Calcareous Topsoils From Fire-Affected Pine Forests in Southeastern Spain. Geoderma 118, 77–88. doi:10.1016/S0016-7061(03)00185-X

McLauchlan, K. K., Higuera, P. E., Miesel, J., Rogers, B. M., Schweitzer, J., Shuman, J. K., et al. (2020). Fire as a Fundamental Ecological Process: Research Advances and Frontiers. J. Ecol. 108 (5), 2047–2069. doi:10.1111/1365-2745.13403

Miyata, S., Kosugi, K. I., Gomi, T., Onda, Y., and Mizuyama, T. (2007). Surface Runoff as Affected by Soil Water Repellency in a Japanese Cypress Forest. Hydrol. Process. 21, 2365–2376. doi:10.1002/hyp.6749

Moore, G., and Blackwell, P. (1998). “Water Repellence,” in Soil Guide: A Handbook for Understanding and Managing Agricultural Soils. Editor G. Moore (Western Australia: Perth: Department of Agriculture), 49–59.

Muñoz-Rojas, M., Erickson, T. E., Martini, D., Dixon, K. W., and Merritt, D. J. (2016). Soil Physicochemical and Microbiological Indicators of Short, Medium and Long Term Post-Fire Recovery in Semi-Arid Ecosystems. Ecol. Indic. 63, 14–22. doi:10.1016/j.ecolind.2015.11.038

Negri, S., Arcenegui, V., Mataix-Solera, J., and Bonifacio, E. (2024). Extreme Water Repellency and Loss of Aggregate Stability in Heat-Affected Soils Around the Globe: Driving Factors and Their Relationships. Catena 244, 108257. doi:10.1016/j.catena.2024.108257

Nelson, D. V., and Sommers, L. E. (1982). “Total Carbon, Organic Carbon, and Organic Matter,” in Methods of Soil Analysis, Part 2. Chemical and Biological Methods. Agronomy Monographs. Editor A. L. Page (Madison, WI: American Society of Agronomy, Inc., Soil Science Society of America, Inc.), 816.

Pausas, J. G., and Keeley, J. E. (2009). A Burning Story: The Role of Fire in the History of Life. BioScience 59 (7), 593–601. doi:10.1525/bio.2009.59.7.10

Pellegrini, A. F., Harden, J., Georgiou, K., Hemes, K. S., Malhotra, A., Nolan, C. J., et al. (2022). Fire Effects on the Persistence of Soil Organic Matter and Long-Term Carbon Storage. Nat. Geosci. 15 (1), 5–13. doi:10.1038/s41561-021-00867-1

Robichaud, P. R., Lewis, S. A., and Ashmun, L. E. (2008). “New Procedure for Sampling Infiltration to Assess Post-Fire Soil Water Repellency,” in Res. Note. RMRS-RN-33 (Fort Collins, CO: US Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station).

Roldán, A., García-Orenes, F., and Lax, A. (1994). An Incubation Experiment to Determine Factors Involving Aggregation Changes in an Arid Soil Receiving Urban Refuse. Soil Biol. biochem. 26, 1699–1707. doi:10.1016/0038-0717(94)90323-9

RStudio Team (2023). RStudio: Integrated Development Environment for R. Posit Software. Boston, MA: PBC. Available at: http://www.posit.co/.

Sánchez-García, C., Revelles, J., Burjachs, F., Euba, I., Expósito, I., Ibáñez, J., et al. (2024). What Burned the Forest? Wildfires, Climate Change and Human Activity in the Mesolithic–Neolithic Transition in SE Iberian Peninsula. Catena 234, 107542. doi:10.1016/j.catena.2023.107542

Scott, D. F. (1992). “The Influence of Vegetation Type on Soil Wettability,” in Proceedings of the 17th Congress of the Soil Science Society of South Africa (University of Stellenbosch), 10B21–10B26.

Shakesby, R. A., and Doerr, S. H. (2006). Wildfire as a Hydrological and Geomorphological Agent. Earth-Sci. Rev. 74, 269–307. doi:10.1016/j.earscirev.2005.10.006

Souza-Alonso, P., Saiz, G., García, R. A., Pauchard, A., Ferreira, A., and Merino, A. (2022). Post-Fire Ecological Restoration in Latin American Forest Ecosystems: Insights and Lessons From the Last Two Decades. For. Ecol. Manag. 509, 120083. doi:10.1016/j.foreco.2022.120083

Wessel, A. T. (1988). On Using the Effective Contact Angle and the Water Drop Penetration Time for Classification of Water Repellency in Dune Soils. Earth Surf. Process. Landf. 13, 555–561. doi:10.1002/esp.3290130609

Keywords: wildfire, Arequipa, Andes, shrubland, soil aggregation

Citation: Coaguila L, Mataix-Solera J, Nina S, García-Carmona M and Salazar ET (2025) Soil Degradation Evidence Following a Wildfire in Arequipa’s Andean Region, Peru. Span. J. Soil Sci. 15:13983. doi: 10.3389/sjss.2025.13983

Received: 25 October 2024; Accepted: 03 January 2025;

Published: 20 January 2025.

Edited by:

Marcos Francos, University of Salamanca, SpainCopyright © 2025 Coaguila, Mataix-Solera, Nina, García-Carmona and Salazar. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Jorge Mataix-Solera, am9yZ2UubWF0YWl4QHVtaC5lcw==

Lunsden Coaguila1

Lunsden Coaguila1 Jorge Mataix-Solera

Jorge Mataix-Solera Minerva García-Carmona

Minerva García-Carmona