Abstract

Attitude toward organ donation mobilizes donation behavior and makes transplant surgery possible. As future health professionals, medical students will be a relevant generating opinion group and will have an important role in the organ requesting process. The goals of this meta-analysis were to obtain polled rates of medical students who are in favor, against, or indecisive toward cadaveric organ donation in the studies conducted around the world, and to explore sociocultural variables influencing the willingness to donate. Electronic search and revision of references from previous literature allowed us to locate 57 studies fulfilling the inclusion criteria. Data extraction and risk of bias assessment were performed by two independent investigators. Pooled estimations were computed assuming a random-effects model. Despite the fact that willingness to donate was elevated in medical students, estimated rates in studies from different geographical areas and sociocultural backgrounds exhibited significant differences. The age and the grade of the students also influenced the rate of students in favor. Donation campaigns should take into account cultural factors, especially in countries where certain beliefs and values could hamper organ donation. Also, knowledge and skills related to organ donation and transplant should be acquired early in the medical curriculum when a negative attitude is less resistant to change.

Introduction

Despite the advances in the field of organ donation and transplant, current rates of donation are still insufficient to cover minimum needs. The organ deficit is the main cause of death in waitlisted patients (1). There are several factors involved in the process of requesting and donating organs for transplants. Sociocultural factors are one of the main sources of variability among studies on the attitudes toward donation. First, geographical area influences the willingness to donate. Differences in organ donation systems and organ requesting protocols in each country mean that even people from similar cultural backgrounds (e.g., Latin) and living in different geographic areas could exhibit different levels of disposition to donate (2). Second, attitudes to donation are dependent on the local cultural and socioeconomic background. Death conceptions, religion, and values must be considered by the organ donation system in each country for transplantation programs to be successful (3, 4). Finally, sociodemographic factors such as age, gender, and educative level have also been shown to have influence on attitudes toward donation and transplant.

Health professionals have an important role in the successful development of the organ donation process (5). In the community context, they are one of the most relevant opinion-generating groups. Moreover, negative attitudes based on information provided by professionals are more resistant to change since they are supported by experts (6). Medical students are the new generation of clinicians, and therefore, the future link between donors and recipients.

Obtaining knowledge about attitudes toward cadaveric organ donation in medical students has been considered of particular importance and exists in a wide range of scientific literature. Research has been conducted in different countries and cultural backgrounds, has examined different dimensions of organ donation attitudes (awareness, willingness, registration, etc.), and has used a variety of methodological procedures. As a consequence, the results reported a high heterogeneity across studies. Despite its extension, the literature has not been systematically integrated and factors behind the heterogeneity of findings have not been explored yet. Meta-analytical procedures could contribute to reaching well-established conclusions about the intention of medical students to donate their organs after death.

Following the PICOS strategy to formulate questions in meta-analyses, the current study intended to answer the following question: what is the rate of medical students (participants) who are in favor (outcome) of donating their organs after death (intervention) in observational studies (study design)? From this question, two goals were considered: 1) to obtain the polled estimated rate of medical students who were in favor, against, or indecisive toward cadaveric organ donation; and 2) to explore sociocultural variables influencing the willingness to donate. We expected that the elevated pooled rate of medical students in favor of cadaveric donation would be superior to rates of students against and indecisive. It is likely that rates of students willing to donate were influenced by potential moderators, such as geographical area, grade of students, and gender.

Materials and Methods

This meta-analysis was performed following the PRISMA 2020 Guideline for Reporting Meta-analyses (7) and the MOOSE Checklist for Meta-analyses of Observational Studies (8). See Supplementary Data Sheet S1.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

To be included in the meta-analysis studies had to fulfill the following eligibility criteria: 1) assess willingness to donate organs after death; 2) report necessary statistics to compute the proportion of participants who are willing to donate (events and sample size); 3) participants were medical students; 4) observational designs without experimental manipulations; and 5) published in English, Spanish, or Portuguese. Studies examining attitudes toward living donation, donation of specific organs, studies that did not report results for medical students separately from samples of other populations (e.g., non-medical students, general public, etc.), and studies sharing samples (totally or partially) with other included studies were excluded. Studies in languages other than English, Spanish, or Portuguese could not be included due to the language limitations of researchers.

Search Strategy

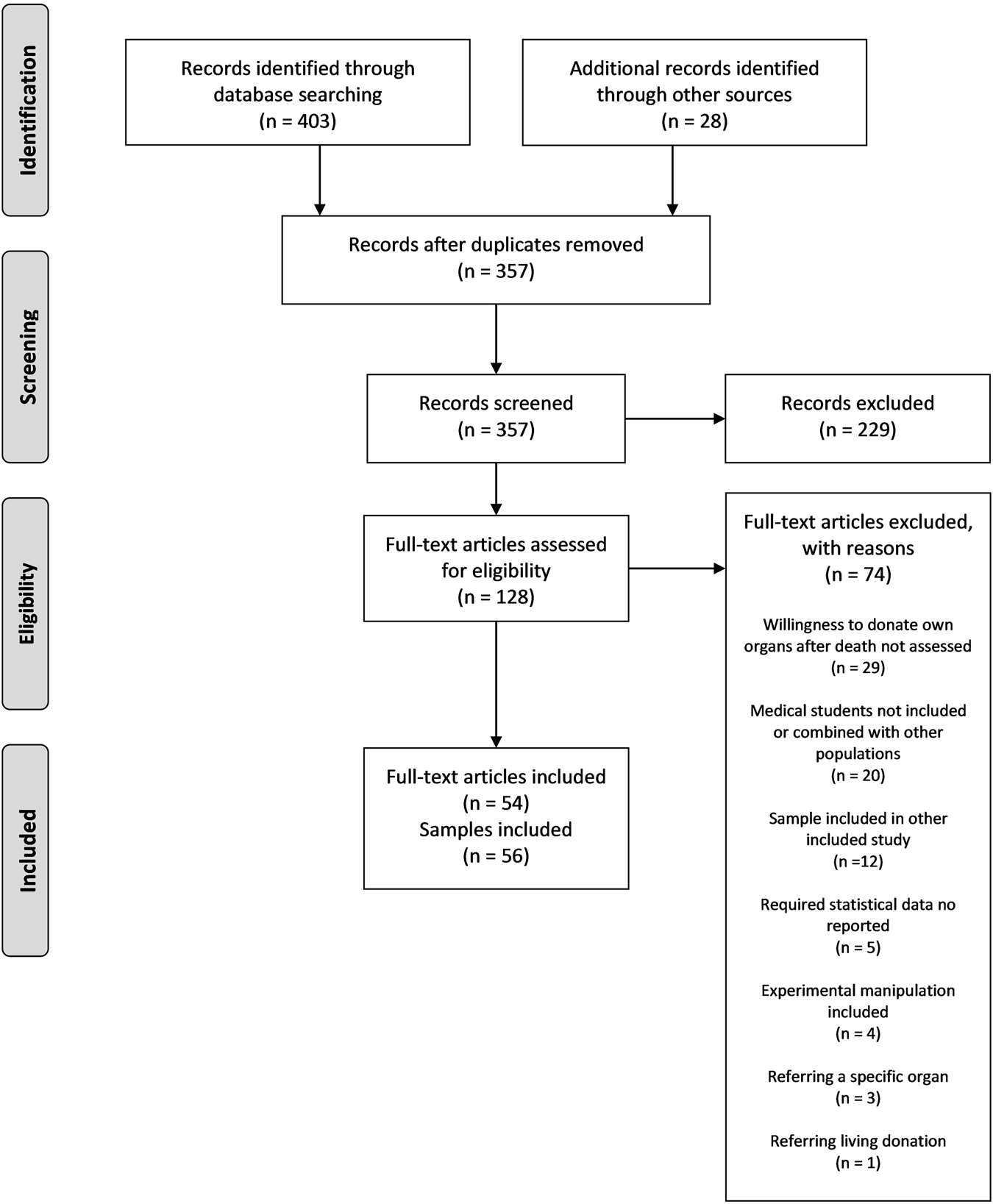

An electronic search was conducted in PubMed, CINALH Complete, PsycInfo, and Psychology and Behavioral Sciences Collection until February 2021. English and Spanish keywords were organ donation AND (attitude OR willingness OR perceptions OR beliefs OR opinions) AND medical students. References of previous meta-analyses (9–11) and studies collected were also screened. Finally, the most prolific authors in the field were contacted to request potential unpublished data. Figure 1 shows the search and eligibility processes in the PRISMA flow diagram.

FIGURE 1

PRISMA flow diagram.

The electronic search yielded 403 outputs, and 28 references were located from previous publications. After deleting duplicates, the title and abstract of 357 papers were reviewed. After excluding a further 229, the full text of 128 articles was reviewed to assess their potential inclusion; 73 articles were rejected due to reasons shown in Figure 1. Finally, 54 papers (12–65) including 56 separate samples fulfilled the inclusion criteria.

Data Extraction

A data extraction protocol including statistics and potential moderator variables was elaborated and applied by two independent investigators to each selected study. Variables concerning participants were: 1) gender (percentage of men); 2) rate of men in favor; 3) rate of women in favor; 4) mean age; 5) the percentage of students in each grade; 6) proportion of first-grade students in favor; 7) proportion of students in the last grade in favor; 8) country of participants; 9) continent; 10) cultural background in the country of participants; and 11) the percentage of participants of each religion. Variables related to the methodology of studies were: 1) year of survey; 2) completion rate; 3) type of measure (interview or self-report); 4) administration modality (face-to-face, online, or both); and 5) methodological quality of the study (rated from 0 to 5, see Quality Assessment section).

Risk of Bias Assessment

To assess the risk of bias in individual studies, a five-item checklist was elaborated based on the STROBE Checklist for cross-sectional studies (66). Items were rated as follows: 1) setting: whether the study provided information about locations, setting, and dates of data collection (1 yes, 0 no); 2) sample size: whether the study explained how the sample size was arrived at (1 yes, 0 no); 3) participants: whether the study reported eligibility criteria and methods of selection of participants (1 yes, 0 no); 4) completion rate: whether the study reported the percentage of distributed surveys that were retrieved (1 yes, 0 no); and 5) outcome: whether the study employed a validated outcome measure or conducted a pilot study prior to its administration (1 yes, 0 no). A methodological quality score was computed as the sum of the five items.

Statistical Analysis

The primary outcome was the pooled estimate rate (proportion) of medical students who were willing to donate organs after death. Rates of students against and indecisive were also extracted as secondary outcomes. Under the assumption that samples of selected studies could be representative of different populations, pooled rates were computed assuming a random-effects model, where each individual proportion was pondered by its precision. Heterogeneity was examined by computing Q statistics and the percentage of the observed variance between studies’ I2. To analyze the effect of potential moderator variables on the primary outcome (rate of students in favor), ANOVAs with QB statistics and meta-regression models with QR statistics were computed for categorical and continuous variables, respectively. The percentage of explained variance was assessed by R2 index (67). Publication bias analysis included the Egger test and the construction of a funnel plot implementing the trim-and-fill method (68). All data analyses were conducted in Comprehensive Meta-Analysis (CMA) 3.0 (69).

Results

Study Characteristics and Risk of Bias

Table 1 shows the main characteristics of the 56 independent studies included in the meta-analysis. Studies were conducted in 25 different countries between 1999 and 2020. The total sample included 33,536 medical students with mean ages between 17.60 and 26.35 years. The percentage of men ranged from 16.6% to 93.8%. The completion rate reported by the studies ranged from 32% to 100%. Concerning the risk of bias, the mean methodological quality was 2.18, with 35.1% of studies having scores ≥3 See Supplementary Table S1.

TABLE 1

| Study | Year of survey | Country | No. of participants | Completion rate, % | Quality, range 1–5 | Age, mean | Men, % | In favor, % | Against, % | Indecisive, % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Akkas et al. (12) | 2013 | Turkey | 100 | 66.80 | 3 | 17.60 | 43.0 | 54.00 | 16.00 | 30.00 |

| Akkas et al. (12) | 2013 | Turkey | 100 | 66.80 | 3 | 24.20 | 56.0 | 70.00 | 14.00 | 16.00 |

| Ali et al. (13) | 2011 | Pakistan | 158 | 81.02 | 3 | 20.00 | 36.7 | 44.94 | — | — |

| Alnajjar et al. (14) | 2019 | Saudi Arabia | 113 | 74.83 | 5 | 20.04 | 93.8 | 55.75 | 8.85 | 35.40 |

| AlShareef et al. (15) | 2016 | Saudi Arabia | 225 | 36.12 | 2 | 22.77 | 68.0 | 38.22 | 19.11 | 42.67 |

| Anwar et al. (16) | 2019 | Bangladesh | 100 | — | 1 | — | — | 28.00 | 16.00 | 48.00 |

| Ashfaq et al. (17) | 2017 | Pakistan | 400 | — | 3 | 20.98 | 50 | 61.25 | — | — |

| Atamañuk et al. (18) | 2016 | Argentina | 1012 | 96.80 | 3 | 21.40 | 35.5 | 81.92 | — | — |

| Bilgel et al. (19) | — | Turkey | 409 | 80.50 | 2 | 20.30 | 49.9 | 58.44 | 22.74 | 18.83 |

| Burra et al. (20) | — | Italy | 100 | 51.30 | 1 | 23.70 | 29.0 | 88.00 | — | — |

| Cahill & Ettarh (21) | 2007 | Ireland | 187 | 87.00 | 2 | — | — | 63.64 | 7.49 | 28.88 |

| Chung et al. (22) | 2006 | China | 655 | 94.00 | 2 | 21.00 | 58.0 | 85.04 | — | — |

| Dahlke et al. (23) | — | Germany | 165 | — | 1 | 21.50 | 35.2 | 56.36 | — | — |

| Dahlke et al. (23) | — | Japan | 99 | — | 1 | 22.40 | 72.7 | 52.53 | — | — |

| Dahlke et al. (23) | — | United States | 66 | — | 1 | 23.90 | 48.5 | 65.15 | — | — |

| Dibaba et al. (24) | 2019 | Ethiopia | 320 | — | 2 | 23.48 | 57.8 | 58.12 | — | — |

| Dutra et al. (25) | 2002 | Brazil | 779 | 77.82 | 2 | 21.90 | 59.5 | 69.06 | 30.68 | — |

| Edwards et al. (26), Essman (29) | 2005 | United States | 500 | 93.00 | 3 | 24.00 | 50.0 | 82.40 | 5.00 | 9.00 |

| El-Agroudy et al. (27) | 2017 | Bahrein | 376 | 75.20 | 2 | 22.10 | 39.1 | 71.81 | 18.88 | 11.97 |

| Englschalk et al. (28) | 2015 | Germany | 181 | 2 | 23.10 | 37.6 | 82.32 | 7.18 | 9.94 | |

| Figueroa et al. (30) | 2011 | Holland | 506 | 84.00 | 3 | 20.76 | 26.6 | 79.84 | 5.73 | 14.03 |

| Galvao et al. (31) | — | Brazil | 347 | 32.00 | 3 | — | — | 89.91 | 10.09 | — |

| Goz et al. (32) | — | Turkey | 213 | 36.91 | 2 | — | — | 56.81 | — | — |

| Hamano et al. (33) | 2018 | Japan | 702 | 100.00 | 2 | 25.00 | — | 54.70 | 13.96 | 31.05 |

| Hasan et al. (34) | 2019 | Pakistan | 157 | 82.00 | 2 | 20.60 | 16.6 | 41.40 | — | — |

| Inthorn et al. (35) | 2009 | Germany | 466 | 95.10 | 2 | — | — | 63.52 | — | — |

| Jamal et al. (36) | 2017 | Pakistan | 150 | 88.50 | 4 | — | 61.33 | — | — | |

| Jung et al. (37) | — | Romania | 140 | — | 0 | 20.50 | 30.0 | 81.43 | 3.57 | 15.00 |

| Kirimlioglu et al. (38) | — | Turkey | 214 | 71.30 | 2 | 20.00 | 45.8 | 22.43 | 27.10 | — |

| Kobus et al. (39) | — | Poland | 203 | — | 0 | 21.80 | - | 94.58 | — | — |

| Kocaay et al. (40) | 2013 | Turkey | 88 | — | 1 | — | — | 60.23 | — | — |

| Kozlik et al. (41) | 2012 | Poland | 400 | — | 2 | 21.80 | 37.3 | 90.50 | 3.00 | 6.50 |

| Lei et al. (42) | 2016 | China | 284 | — | 2 | — | 15.14 | — | — | |

| Lima et al. (43) | 2007 | Brazil | 300 | 85.70 | 3 | — | 51.0 | 62.00 | — | — |

| Liu et al. (44) | 2019 | China | 1363 | 90.90 | 2 | 21.5 | 39.5 | 62.73 | 37.27 | |

| Marques et al. (45) | 2008 | Puerto Rico | 227 | 76.70 | 3 | — | 49.1 | 88.55 | 11.01 | — |

| Marván et al. (46) | 2018 | Mexico | 205 | — | 3 | — | 48.3 | 91.71 | — | — |

| Mekahli et al. (47) | 2006 | France | 571 | — | 1 | 18.50 | 34.5 | 81.09 | 13.49 | 5.43 |

| Naçar et al. (48) | 2014 | Turkey | 464 | 94.70 | 1 | 20.90 | 48.9 | 50.00 | 5.82 | 44.18 |

| Najafizadeh et al. (49) | 2006 | Iran | 41 | — | 1 | 22.80 | 44.0 | 87.80 | 4.88 | — |

| Ohwaki et al. (50) | 2004 | Japan | 388 | 100.00 | 2 | — | 74.0 | 59.02 | 15.98 | 21.91 |

| Ríos et al. (51) | 2011 | Spain | 9275 | 95.70 | 5 | 21.00 | 28.2 | 79.53 | 1.66 | 18.91 |

| Rydzewska et al. (52) | — | Poland | 569 | — | 0 | 21.77 | 25.8 | 92.97 | 2.46 | 4.57 |

| Sağiroğlu et al. (53) | 2012 | Turkey | 356 | 71.80 | 2 | 20.40 | 49.44 | 16.85 | 33.71 | |

| Sahin and Abbasoglu (54) | 2013 | Several countries | 1541 | — | 2 | 21.80 | 41.0 | 94.35 | 1.36 | 4.28 |

| Sampaio et al. (55) | — | Brazil | 518 | 49.01 | 1 | — | 25.9 | 84.94 | 1.35 | 13.71 |

| Sanavi et al. (56) | 2008 | Iran | 262 | 97.00 | 1 | 22.10 | 32.0 | 85.11 | — | — |

| Sayedalamin et al. (57) | 2014 | Saudi Arabia | 481 | — | 2 | 21.39 | 48.0 | 31.81 | 68.19 | — |

| Sebastián-Ruiz et al. (58) | 2015 | Mexico | 3056 | — | 2 | 20.30 | 53.3 | 73.99 | 26.01 | — |

| Tagizadieh et al. (59) | 2016 | Iran | 400 | — | 2 | 26.35 | 59.0 | 85.00 | 15.00 | — |

| Tuesca et al. (60) | 1999 | Colombia | 993 | 84.27 | 5 | 25.00 | 52.6 | 84.79 | 6.65 | 8.56 |

| Tumin et al. (61) | 2014 | Malaysia | 264 | 88.00 | 4 | — | — | 72.73 | — | — |

| Verma et al. (62) | — | India | 1463 | 73.00 | 3 | - | 44.9 | 65.62 | 34.38 | — |

| Wu et al. (63) | — | China | 264 | 88.00 | 3 | 20.25 | 29.5 | 39.77 | 42.05 | 18.18 |

| Zahmatkeshan et al. (64) | 2012 | Iran | 340 | — | 3 | — | — | 79.12 | 9.41 | 11.47 |

| Zhang et al. (65) | — | China | 199 | — | 1 | — | 43.2 | 32.16 | 27.14 | 40.70 |

Summary of the included studies.

Pooled Rates of Medical Students in Favor, Against, and Indecisive

Table 2 shows combined estimated proportions and confidence intervals for each outcome in the meta-analysis. In the primary outcome, a combined percentage of 69.2% (95% CI: 64.7%–73.4%) of medical students was willing to donate their organs after death. Significant and high heterogeneity was observed (I2 = 98.25%). Regarding secondary outcomes, the pooled estimation of students against donating, including 36 studies, was 11.7% (95% CI: 8.4%–16.1%) and the pooled estimation for indecisive students, including 27 studies, was 17.7% (95% CI: 14%–22%). Heterogeneity tests showed significant and high variability among studies in both against (I2 = 98.82%) and indecisive (I2 = 97.33%) participants.

TABLE 2

| Outcome | K | Q | I 2 | p + | 95% C.I. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| l l | l u | |||||

| Students in favor | 56 | 3144.31*** | 98.25 | 0.692 | 0.647 | 0.734 |

| Students against | 36 | 2978.40*** | 98.82 | 0.117 | 0.084 | 0.161 |

| Indecisive students | 27 | 973.39*** | 97.33 | 0.177 | 0.140 | 0.220 |

Pooled estimated rates, confidence intervals, and heterogeneity indexes for study outcomes.

C.I., confidence interval; k, number of studies; Q, heterogeneity statistic; I2, heterogeneity index; p+, pooled estimated rate, lI and lu, lower and upper confidence limits.

***p < 0.001.

Factors Influencing the Willingness to Donate

Participant-Related Variables

Continent, Culture, and Religion

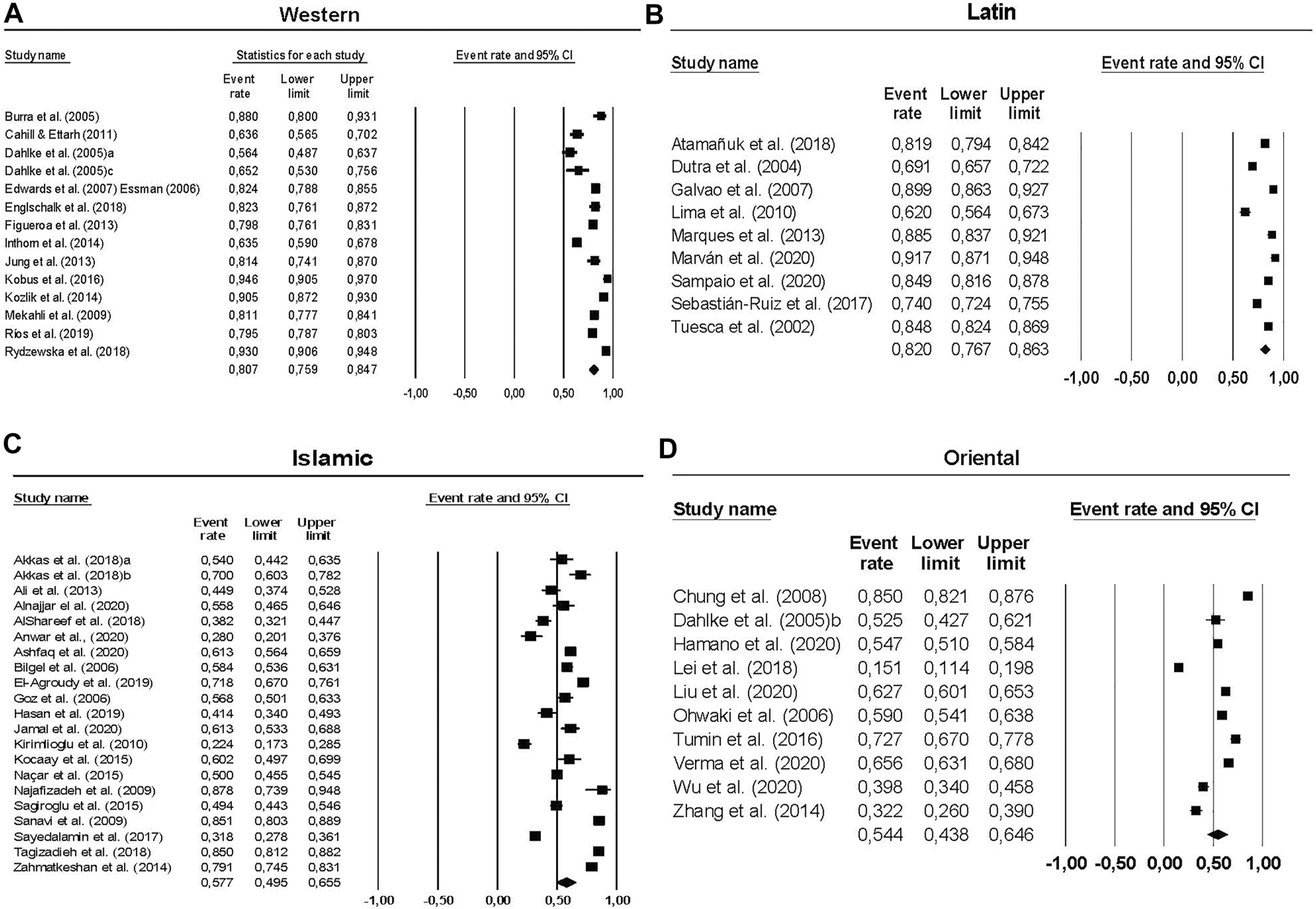

Significant differences were observed depending on the continent where the study was conducted (Q3 = 27.13, p <0.000). The highest pooled rates of students in favor were obtained by the studies conducted in North America (k = 2, p+ = 0.753, 95% CI [0.554, 0.882]), Latin America (k = 9, p+ = 0.820, 95% CI [0.767, 0.863]), and Europe (k = 20, p = 0.718, 95% CI [0.642, 0.784]) which were significantly superior to the pooled rate for studies in Asia (k = 23, p+ = 0.580, 95% CI [0.503, 0.654]). Given these results, and to obtain a more accurate view of differences, we considered grouping studies by predominant culture in the country of participants. Figure 2 shows forest plots of pooled estimations for each cultural background and individual rates for each study. Cultural background significantly influenced the willingness to donate (Q3 = 49.850, p < 0.000). Higher rates were observed for studies in countries with Latin (k = 9, p+ = 0.820, 95% CI [0.767, 0.863]) and Western (k = 14, p+ = 0.807, 95% CI [0.760, 0.850]) cultural backgrounds, finding significant differences with Islamic (k = 21, p+ = 0.577, 95% CI [0.495, 0.655]) and Oriental (k = 10, p+ = 0.544, 95% CI [0.438, 0.646]) countries. Regarding religion, the percentage of Catholic students showed a positive and significant relationship with the proportion of students in favor (k = 15, bj = 0.02, Q1 = 28.09, p <0 .000, R2 = 0.44) whereas the percentage of Muslim students was not related to the rate of students in favor (k = 10, bj = −0.01, Q1 = 2.13, p = 0.144, R2 = 0.00). The influence of the percentage of students affiliated with other religions could not be analyzed due to the reduced number of studies that reported these data.

FIGURE 2

Forest plots of individual rates and confidence intervals for each study (squares) and pooled estimations and confidence intervals for each cultural background (diamonds). (A) Forest plot of individual and pooled rates of students willing to donate in Western countries. Individual rates vary from 0.564 to 0.940. The pooled estimated rate by the random-effects model was 0.807. (B) Forest plot of individual and pooled rates of students willing to donate in Latin countries. Individual rates vary from 0.620 to 0.917. The pooled estimated rate by the random-effects model was 0.820. (C) Forest plot of individual and pooled rates of students willing to donate in Islamic countries. Individual rates vary from 0.224 to 0.878. The pooled estimated rate by the random-effects model was 0.577. (D) Forest plot of individual and pooled rates of students willing to donate in Oriental countries. Individual rates vary from 0.151 to 0.850. The pooled estimated rate by the random-effects model was 0.544.

Age and Grade of Participants

The mean age of participants showed a significant and positive relationship with the proportion of students in favor of donating (k = 39, bj = 0.16, Q1 = 4.85, p = 0.024, R2 = 0.10) explaining 10% of the variance. Results of meta-regression analyses showed that percentages of students in 2nd, 3rd, 4th, 5th, and 6th grade included in the studies, were not significant predictors of the willingness to donate (p >0 .05). Only the percentage of first-grade students showed a significant and negative relationship with the proportion of students in favor of donation (k = 25, bj = -0.01, Q1 = 4.75, p = 0.029, R2 = 0.06) with 6% of the accounted variance. There were marginally significant differences between first-grade (k = 13, p+ = 0.65, 95% CI [0.55, 0.73]) and sixth-grade students (k = 10, p+ = 0.79, 95% CI [0.67, 0.87]) according to the subgroup analysis (Q1 = 3.79, p = 0.052).

Gender

The percentage of men was not a significant predictor of the willingness to donate (k = 43, bj = −0.02, Q1 = 2.56, p = 0.11, R2 = 0.00). Similarly, subgroup analysis did not yield significant differences (Q1 = 1.487, p = 0.223) in the proportion of men (k = 9, p+ = 0.61, 95% CI [0.52, 0.69]) and women (k = 9, p+ = 0.68, 95% CI [0.59, 0.77]) in favor.

Methodological Variables

Meta-regression analysis revealed that the completion rate (k = 34, bj = 0.00, Q1 = 0.02, p = 0.900, R2 = 0.00) and the methodological quality score (k = 56, bj = −0.03, Q1 = 0.06, p = 0.810, R2 = 0.00) were not significantly associated with the proportion of students willing to donate. Only the year of survey (k = 41, bj = −0.07, Q1 = 8.79, p = 0.003, R2 = 0.08) was negatively associated with the rate of students in favor. There were not significant differences between face-to-face (k = 48, p+ = 0.68, 95% CI [0.64, 0.73]) and online (k = 6, p+ = 0.68, 95% CI [0.46, 0.85]) administration (Q1 = 0.000, p = 0.997).

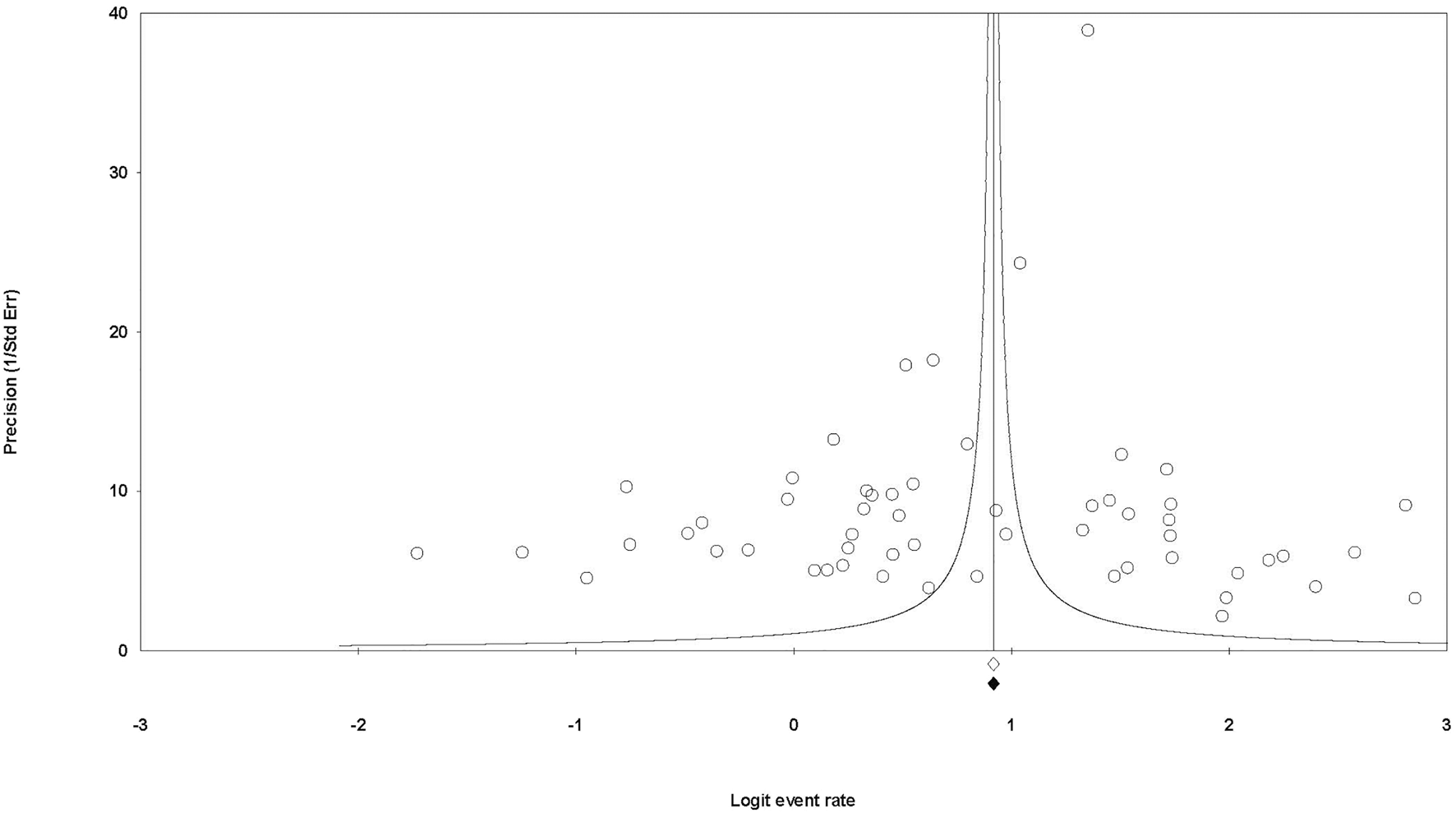

Publication Bias Analysis

First, results from Egger’s test were not significant (b0 = −2.89; t[54] = 1.60, p = 0.115), supporting the absence of publication bias. Second, after the implementation of the trim-and-fill method, it was not necessary to introduce imputed values into the funnel plot to reach symmetry (Figure 3), with the pooled proportion of adjusted values equal to the pooled proportion of observed values.

FIGURE 3

Funnel plot of the individual observed rates for each study (circles) and observed (white diamond) and adjusted (black diamond) pooled rates of students willing to donate. The absence of imputed values to achieve symmetry in the dots’ distribution and the equivalence between observed and adjusted pooled rates allow for us to discard publication bias.

Discussion

This is the first meta-analysis on the willingness to donate in medical students. Similarly, this is the first work analyzing cultural and individual variables as potential explaining factors of the variability of results reported by studies around the world. Results have revealed a pooled rate of close to 70% of students willing to donate their organs after death. This is higher than the observation in studies conducted with the general public in different countries (10, 70–72) supporting that medical students have a heightened awareness of organ donation, similar to students from other health disciplines (32, 73, 74).

However, results in primary studies exhibited high heterogeneity, pointing to the presence of factors influencing willingness to donate. Both geographical area (continent) and cultural background had significant effects on the rate of students in favor. Studies conducted in countries with Latin (82%) and Western (70.6%) cultures obtained the greatest percentages, followed by Islamic countries (57.7%) and studies in countries with an Oriental culture (54.4%) which obtained the lowest percentage. These results are in line with previous literature. The meta-analysis by Mekkodathil et al. (10), including studies with the general public from Islamic countries, reported a pooled percentage of favorable attitude toward donation of less than 50%. Also, studies conducted with Asian populations have reported reduced rates of donation intention and registration among students, health workers, and the general public (75).

Sociocultural background includes social, spiritual, religious, and family beliefs and values that affect the decision-making process about donation. Regarding medical students in Islamic countries, motives related to body preservation after death were reported by students against donating their organs in some included studies (15, 19, 49, 54, 65). Conversely, the percentage of students worried about the mutilation of the body after death was considerably low in studies conducted in Western (30, 52) and Latin (59) cultural backgrounds. As in Western (26, 30, 40, 52, 76) or Latin countries (31, 59, 61) religious motives against donation were reported by reduced percentages of medical students in studies conducted in Turkey (32, 39, 49, 54). However, knowing the attitude toward donation and transplant promoted by participants’ own religion can influence individual attitudes. In some included studies conducted in Saudi Arabia, Turkey, and Iran, about 30% of medical students ignored whether religion was in favor of donation and transplant (15, 41, 60). By contrast, in countries with high predisposition rates such as Spain, only 12% of medical students did not know their religion’s posture on donation and transplant (52).

In countries with a predominant Oriental culture, family opinion about donation seemed to be of particular importance. In the study by de Ohwaki et al. (51), more than 65% of medical students stated that their families would disagree with organ donation. Similarly, Lei et al. (43) observed that 95.5% of the students with no favorable attitude believed that their family was against donation. Oriental culture confers to family a relevant role in the life of individuals. Traditional values emphasized family interests over the individual’s ones (43). Although in a Western or Latin cultural context, family’s opinion influences the willingness to donate (52), the percentages of students who had discussed donation with their family (60%–70%) were considerably elevated (18, 26, 52, 59). Also in these countries, it has been reported that elevated proportions of medical students think that their parents’ opinion is favorable (52, 59). Therefore, the family would play a beneficial role to promote favorable attitudes in Western and Latin cultural contexts. The importance of body preservation is another factor that affects the intention to donate after death in Asian medical students. A high percentage of students recognized concerns about body mutilation in the organ extraction process in some studies (22, 43). The Confucian heritage that promotes the idea of body care as a way of respect to parents, together with beliefs related to life after death, contributes to the importance of body preservation after death in Oriental cultures (75). As commented, the importance of body preservation was not a relevant reason against donation in cultural contexts with high rates of willingness to donate, being more rated than other motives such as the lack of information (26, 52, 59) and fear of trafficking or fair organ allocation (26, 52, 59).

According to the reports from the Global Observatory on Donation and Transplantation (77) in 2020, cultural differences observed in willingness to donate could be reflected by the rates of deceased donors in the countries of studies included in this meta-analysis. Using the same classification by cultural background, the highest mean of deceased donors per million population was observed in Western countries (16.38), followed by the mean in Latin (7.40), Islamic (3.86), and Oriental (1.69) countries. As it can be seen, the trend was similar to the observed willingness to donate, except for Latin countries, in which despite having an elevated rate of students in favor in this meta-analysis, the rates of deceased donors were discrete and lower than in Western countries. Possible explanations for this difference are that medical students were not representative of the general population in Latin America and that in addition to the attitudes, there were other variables (economic, related to donation system, etc.) influencing the factual deceased donor rates.

Age was positively related to the rate of students in favor. Given that the population studied in this meta-analysis was medical students, whose level of knowledge rises yearly, it is highly probable that the change in their perspective would be due to the educational level more than to the age effect itself. In fact, the percentage of first-grade students included had a negative impact on the proportion of students in favor. Moreover, the subgroup analysis revealed differences between first- (65%) and sixth-grade students (79%). Taken together, these results may support the positive influence of years of training received by the students on their willingness to donate. It has been demonstrated that knowledge about aspects related to donation and transplant has a positive impact on attitudes toward donation (30, 52, 78). In addition, students in more advanced grades could have more opportunities for contact with transplant patients and donors or have attended campaigns or workshops to promote awareness toward donation. These experiences have also shown beneficial effects on the attitude to donation (18, 52).

In this meta-analysis, gender was not significantly related to the rate of students in favor, whereas individual studies have shown contradictory findings: existing studies where women exhibited a more favorable attitude (19, 32, 52) and studies where significant differences were not observed (27). Despite the fact that our findings revealed a higher rate for women (68%) than for men (61%), the reduced number of subgroups included in the analysis could explain the absence of significant differences.

Regarding methodological variables, the completion rate did not affect the rate of students willing to donate. Percentage of response could be a risk of bias indicator in attitudinal studies since higher participation could be associated with greater interest in the topic, or even with a more favorable attitude. As a consequence, it would be desirable that at least 75% of spread surveys could be included in the analysis (78). In this meta-analysis, 80% of studies that reported the completion rate showed percentages over 70%. This fact could explain the absence of significant effects on the willingness to donate. Remarkably, 39% of the included studies did not report the completion rate. The modality of administration of surveys (face-to-face vs. online) also affected the rate of students in favor, when taking into account that only six studies used online surveys. Finally, the year in which the survey was conducted showed an inverse association with the rate in favor, pointing to the absence of an increasing trend in the willingness to donate through the years.

The findings of this meta-analysis must be interpreted attending to some limitations. First, some of the studies included presented low scores in methodological quality assessment. The absence of sample size estimation procedures, the absence of random sampling, and the use of non-validated measures were the main weaknesses in the included studies. This could lead to bias in sample representativeness, and variability in the measurement of the willingness to donate. Despite this, it is remarkable that neither the risk of bias nor other methodological variables had a significant impact on the rate of students in favor. Second, all studies used self-report measures. Therefore, inherent disadvantages to self-reports in attitudinal studies (e.g., the trend to answer in a socially desirable way) could affect our results. Third, relevant variables such as discussing organ donation with family, contact with patients and donors, and frequency of other altruistic activities could not be analyzed as influencing factors because they were not reported by enough studies.

Despite these limitations, these results suggest practical implications for medical curriculum design. According to our findings, medical students present a high willingness to donate their organs, improving their attitudes as they progress in their medical careers. However, the percentage of students against and indecisive is still considerable. This picture is heterogeneous around the world, in which there are remarkable differences depending on the sociocultural background which students are immersed. This meta-analysis has evidenced that countries with Oriental and Islamic cultures showed the lowest rates of medical students willing to donate their organs after death. As commented, these studies have shown that the major reasons behind poor donation rates are cultural-related myths, lack of information, and religious misconceptions. In recent years, some countries in these cultural backgrounds have made efforts to include organ donation and transplantation contents in the medical curriculum. However, these modifications have been mainly focused on the acquisition of knowledge (brain death concept, organ donation system functioning, waitlists, etc.) ignoring the approach to sociocultural and religious issues (79). In order to address cultural issues in the medical curriculum, the following aspects are considered of particular importance: 1) promoting the discussion of the topic with family, 2) providing information about the local religion’s attitude to donation, 3) discussing cultural-related death conceptions, and 4) providing reliable information about body manipulations in the donation process. Besides addressing cultural barriers, the possibility of taking advantage of certain cultural values to promote organ donation has been highlighted, for example, the Confucian values of helping others and positive life attitude in Chinese society (80). Knowledge and skills related to organ donation and transplant should be addressed early (first years) in the medical curriculum. This allows for saving resources from campaigns in medical professionals whose negative attitude is more resistant to change (6).

Given that the development of culture-specific campaigns and study plans implies being aware of beliefs, values, and practices of different population groups, future research should examine more deeply culture‐bound conceptualizations of death, organ donation, and other related aspects. Moreover, recommendations for the medical curriculum could be extrapolated to other relevant population targets, especially in educative contexts. This would be the case for adolescents, who are immersed in the development of their own system of values and attitudes.

Statements

Author contributions

MI-S: Conception and design, study search and data extraction, statistical analysis, interpretation of data, drafting of the manuscript, critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content, and final approval of the version to be published. AL-N: Study search and data extraction, drafting of the manuscript, critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content, and final approval of the version to be published. PG: Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content, obtaining funding for this project or study, and final approval of the version to be published. PR: Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content and final approval of the version to be published. AR: Conception and design, study search and data extraction, interpretation of data, drafting of the manuscript, and final approval of the version to be published.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontierspartnerships.org/articles/10.3389/ti.2022.10446/full#supplementary-material

References

1.

Council of Europe. International Figures on Donation and Transplantation (2018). Available at: http://www.ont.es/publicaciones/Documents/NEWSLETTER%202019_completo%20integrada%20cubierta.pdf (Accessed February 20, 2021).

2.

Ríos A Sánchez‐Martínez A Ayala‐García MA Gutiérrez PR Palacios G Iniesta‐Sepúlveda M et al International Population Study in Spain, Cuba, and the United States of Attitudes toward Organ Donation Among the Cuban Population. Liver Transplant (2021). 28:581–92. in press. 10.1002/lt.26338

3.

Huang J Millis JM Mao Y Millis MA Sang X Zhong S . Voluntary Organ Donation System Adapted to Chinese Cultural Values and Social Reality. Liver Transpl (2015). 21(4):419–22. 10.1002/lt.24069

4.

Ali A Ahmed T Ayub A Dano S Khalid M El‐Dassouki N et al Organ Donation and Transplant: The Islamic Perspective. Clin Transpl (2020). 34(4):e13832. 10.1111/ctr.13832

5.

Ríos A Ramírez P Martínez L Montoya MJ Lucas D Alcaraz J et al Are Personnel in Transplant Hospitals in Favor of Cadaveric Organ Donation? Multivariate Attitudinal Study in a Hospital with a Solid Organ Transplant Program. Clin Transpl (2006). 20(6):743–54. 10.1111/j.1399-0012.2006.00562.x

6.

Conesa Bernal C Ríos Zambudio A Ramírez Romero P Rodríguez Martínez M Canteras Jordana M Parrilla Paricio P . Importancia de los profesionales de atención primaria en la educación sanitaria de la donación de órganos. Aten Primaria (2004). 34:528–33. 10.1157/13069582

7.

Page MJ McKenzie JE Bossuyt PM Boutron I Hoffmann TC Mulrow CD et al The PRISMA 2020 Statement: An Updated Guideline for Reporting Systematic Reviews. BMJ (2021). 372:n71. 10.1136/bmj.n71

8.

Stroup DF Berlin JA Morton SC Olkin I Williamson GD Rennie D et al Meta-analysis of Observational Studies in Epidemiology: A Proposal for Reporting. JAMA (2000). 283(15):2008–12. 10.1001/jama.283.15.2008

9.

Feeley TH . College Students' Knowledge, Attitudes, and Behaviors Regarding Organ Donation: An Integrated Review of the Literature. J Appl Soc Pyschol (2007). 37(2):243–71. 10.1111/j.0021-9029.2007.00159.x

10.

Mekkodathil A El-Menyar A Sathian B Singh R Al-Thani H . Knowledge and Willingness for Organ Donation in the Middle Eastern Region: A Meta-Analysis. J Relig Health (2020). 59(4):1810–23. 10.1007/s10943-019-00883-x

11.

Nijkamp M Hollestelle M Zeegers M van den Borne B Reubsaet A . To Be(come) or Not to Be(come) an Organ Donor, That's the Question: A Meta-Analysis of Determinant and Intervention Studies. RHPR (2008). 2(1):20–40. 10.1080/17437190802307971

12.

Akkas M Anık EG Demir MC İlhan B Akman C Ozmen MM et al Changing Attitudes of Medical Students Regarding Organ Donation from a University Medical School in Turkey. Med Sci Monit (2018). 24:6918–24. 10.12659/MSM.912251

13.

Ali NF Qureshi A Jilani BN Zehra N . Knowledge and Ethical Perception Regarding Organ Donation Among Medical Students. BMC Med Ethics (2013). 14:38. 10.1186/1472-6939-14-38

14.

Alnajjar H Alzahrani M Alzahrani M Banweer M Alsolami E Alsulami A . Awareness of Brain Death, Organ Donation, and Transplantation Among Medical Students at Single Academic institute. Saudi J Anaesth (2020). 14(3):329–34. 10.4103/sja.SJA_765_19

15.

AlShareef S Smith R . Saudi Medical Students Knowledge, Attitudes, and Beliefs with Regard to Organ Donation and Transplantation. Saudi J Kidney Dis Transpl (2018). 29(5):1115–27. 10.4103/1319-2442.243963

16.

Anwar ASMT Lee J-M . A Survey on Awareness and Attitudes toward Organ Donation Among Medical Professionals, Medical Students, Patients, and Relatives in Bangladesh. Transplant Proc (2020). 52(3):687–94. 10.1016/j.transproceed.2019.12.045

17.

Ashfaq A Tariq S Awan S Sarafraz R Sultana A Meraj L . Knowledge, Attitude and Practices of Medical Undergraduates of Rawalpindi Medical University Regarding Potential Organ Donation. J Pak Med Assoc (2020). 70(10):1–1788. 10.5455/jpma.301449

18.

Atamañuk AN Ortiz Fragola JP Giorgi M Berreta J Lapresa S Ahuad-Guerrero A et al Medical Students' Attitude toward Organ Donation: Understanding Reasons for Refusal in Order to Increase Transplantation Rates. Transplant Proc (2018). 50(10):2976–80. 10.1016/j.transproceed.2018.04.062

19.

Bilgel H Sadikoglu G Bilgel N . Knowledge and Attitudes about Organ Donation Among Medical Students. Transplantationsmedizin (2006). 18(2):91–6.

20.

Burra P De Bona M Canova D D'Aloiso MC Germani G Rumiati R et al Changing Attitude to Organ Donation and Transplantation in University Students during the Years of Medical School in Italy. Transplant Proc (2005). 37(2):547–50. 10.1016/j.transproceed.2004.12.255

21.

Cahill KC Ettarh RR . Attitudes to Cadaveric Organ Donation in Irish Preclinical Medical Students. Anat Sci Ed (2011). 4(4):195–9. 10.1002/ase.236

22.

Chung CK Ng CW Li JY Sum KC Man AH Chan SP et al Attitudes, Knowledge, and Actions with Regard to Organ Donation Among Hong Kong Medical Students. Hong Kong Med J (2008). 14(4):278–85.

23.

Dahlke MH Popp FC Eggert N Hoy L Tanaka H Sasaki K et al Differences in Attitude toward Living and Postmortal Liver Donation in the United States, Germany, and Japan. Psychosomatics (2005). 46(1):58–64. 10.1176/appi.psy.46.1.58

24.

Dibaba FK Goro KK Wolide AD Fufa FG Garedow AW Tufa BE et al Knowledge, Attitude and Willingness to Donate Organ Among Medical Students of Jimma University, Jimma Ethiopia: Cross-Sectional Study. BMC Public Health (2020). 20(1):799. 10.1186/s12889-020-08931-y

25.

Dutra MMD Bonfim TAS Pereira IS Figueiredo IC Dutra AMD Lopes AA . Knowledge about Transplantation and Attitudes toward Organ Donation: A Survey Among Medical Students in Northeast Brazil. Transplant Proc (2004). 36(4):818–20. 10.1016/j.transproceed.2004.03.066

26.

Edwards TM Essman C Thornton JD . Assessing Racial and Ethnic Differences in Medical Student Knowledge, Attitudes and Behaviors Regarding Organ Donation. J Natl Med Assoc (2007). 99(2):131–7.

27.

El-Agroudy A Jaradat A Arekat M Hamdan R AlQarawi N AlSenan Z et al Survey of Medical Students to Assess Their Knowledge and Attitudes toward Organ Transplantation and Donation. Saudi J Kidney Dis Transpl (2019). 30(1):83–96. 10.4103/1319-2442.252936

28.

Englschalk C Eser D Jox RJ Gerbes A Frey L Dubay DA et al Benefit in Liver Transplantation: A Survey Among Medical Staff, Patients, Medical Students and Non-medical university Staff and Students. BMC Med Ethics (2018). 19(1):7. 10.1186/s12910-018-0248-7

29.

Essman C Thornton J . Assessing Medical Student Knowledge, Attitudes, and Behaviors Regarding Organ Donation. Transplant Proc (2006). 38(9):2745–50. 10.1016/j.transproceed.2006.08.127

30.

Figueroa CA Mesfum ET Acton NT Kunst AE . Medical Students' Knowledge and Attitudes toward Organ Donation: Results of a Dutch Survey. Transplant Proc (2013). 45(6):2093–7. 10.1016/j.transproceed.2013.02.135

31.

Galvao FHF Caires RA Azevedo-Neto RS Mory EK Figueira ERR Otsuzi TS et al Attitude and Opinion of Medical Students about Organ Donation and Transplantation. Rev Assoc Med Bras (2007). 53(5):401–6. 10.1590/S0104-42302007000500015

32.

Goz F Goz M Erkan M . Knowledge and Attitudes of Medical, Nursing, Dentistry and Health Technician Students towards Organ Donation: A Pilot Study. J Clin Nurs (2006). 15(11):1371–5. 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2006.01431.x

33.

Hamano I Hatakeyama S Yamamoto H Fujita T Murakami R Shimada M et al Survey on Attitudes toward Brain-Dead and Living Donor Transplantation in Medical Students: A Cross-Sectional Study in Japan. Clin Exp Nephrol (2020). 24(7):638–45. 10.1007/s10157-020-01878-9

34.

Hasan H Zehra A Riaz L Riaz R . Insight into the Knowledge, Attitude, Practices, and Barriers Concerning Organ Donation Amongst Undergraduate Students of Pakistan. Cureus (2019). 11(8):e5517. 10.7759/cureus.5517

35.

Inthorn J Wöhlke S Schmidt F Schicktanz S . Impact of Gender and Professional Education on Attitudes towards Financial Incentives for Organ Donation: Results of a Survey Among 755 Students of Medicine and Economics in Germany. BMC Med Ethics (2014). 15:56. 10.1186/1472-6939-15-56

36.

Jamal M Khalid M Mubeen S Sheikh M . Comparison of Medical and Allied Health Students' Attitudes on Organ Donation: Case Study from a Private university in Karachi (Short Report). J Pak Med Assoc (2019). 70(2):1–385. 10.5455/jpma.19684

37.

Jung H . Reluctance to Donate Organs: A Survey Among Medical Students. Transplant Proc (2013). 45(4):1303–4. 10.1016/j.transproceed.2013.02.037

38.

Kirimlioglu N Elçioglu Ö . The Viewpoints of Law and Medical Faculty Students on Organ Donation and Transplantation: A Study in Turkey. Turkiye Klin J Med Sci (2010). 30(3):829–37.

39.

Kobus G Reszec P Malyszko JS Małyszko J . Opinions and Attitudes of University Students Concerning Organ Transplantation. Transplant Proc (2016). 48(5):1360–4. 10.1016/j.transproceed.2016.01.045

40.

Kocaay AF Celik SU Eker T Oksuz NE Akyol C Tuzuner A . Brain Death and Organ Donation: Knowledge, Awareness, and Attitudes of Medical, Law, Divinity, Nursing, and Communication Students. Transplant Proc (2015). 47(5):1244–8. 10.1016/j.transproceed.2015.04.071

41.

Koźlik P Pfitzner R Nowak E Kozynacka A Durajski Ł Janik Ł et al Correlations between Demographics, Knowledge, Beliefs, and Attitudes Regarding Organ Transplantation Among Academic Students in Poland and Their Potential Use in Designing Society-wide Educational Campaigns. Transplant Proc (2014). 46(8):2479–86. 10.1016/j.transproceed.2014.09.143

42.

Lei L Deng J Zhang H Dong H Luo Y Luo Y . Level of Organ Donation-Related Knowledge and Attitude and Willingness toward Organ Donation Among a Group of University Students in Western China. Transplant Proc (2018). 50(10):2924–31. 10.1016/j.transproceed.2018.02.095

43.

Lima CX Lima MVB Cerqueira RG Cerqueira TG Ramos TS Nascimento M et al Organ Donation: Cross-Sectional Survey of Knowledge and Personal Views of Brazilian Medical Students and Physicians. Transplant Proc (2010). 42(5):1466–71. 10.1016/j.transproceed.2009.11.055

44.

Liu C Liu S Liu B . Medical Students' Attitudes toward Deceased Organ Donation in China: A Cross Section Cohort Study. Transplant Proc (2020). 52(10):2890–4. 10.1016/j.transproceed.2020.02.167

45.

Marqués-Lespier JM Ortiz-Vega NM Sánchez MC Sánchez MC Soto-Avilés OE Torres EA . Knowledge of and Attitudes toward Organ Donation: A Survey of Medical Students in Puerto Rico. P R Health Sci J (2013). 32(4):187–93.

46.

Marván ML Orihuela-Cortés F Álvarez del Río A . General Knowledge and Attitudes toward Organ Donation in a Sample of Mexican Medical and Nursing Students. Rev Cienc Salud (2020). 18(2):1–19. 10.12804/revistas.urosario.edu.co/revsalud/a.9240

47.

Mekahli D Liutkus A Fargue S Ranchin B Cochat P . Survey of First-Year Medical Students to Assess Their Knowledge and Attitudes toward Organ Transplantation and Donation. Transplant Proc (2009). 41(2):634–8. 10.1016/j.transproceed.2008.12.011

48.

Naçar M Çetinkaya F Baykan Z Elmalı F . Knowledge Attıtudes and Behavıors about Organ Donatıon Among First- and Sixth-Class Medıcal Students: A Study from Turkey. Transplant Proc (2015). 47(6):1553–9. 10.1016/j.transproceed.2015.02.029

49.

Najafizadeh K Shiemorteza M Jamali M Ghorbani F Hamidinia S Assan S et al Attitudes of Medical Students about Brain Death and Organ Donation. Transplant Proc (2009). 41(7):2707–10. 10.1016/j.transproceed.2009.06.147

50.

Ohwaki K Yano E Shirouzu M Kobayashi A Nakagomi T Tamura A . Factors Associated with Attitude and Hypothetical Behaviour Regarding Brain Death and Organ Transplantation: Comparison between Medical and Other University Students. Clin Transpl (2006). 20(4):416–22. 10.1111/j.1399-0012.2006.00494.x

51.

Ríos A López-Navas A López-López A Gómez FJ Iriarte J Herruzo R et al A Multicentre and Stratified Study of the Attitude of Medical Students towards Organ Donation in Spain. Ethn Health (2019). 24(4):443–61. 10.1080/13557858.2017.1346183

52.

Rydzewska M Drobek NA Małyszko ME Zajkowska A Malyszko J . Opinions and Attitudes of Medical Students about Organ Donation and Transplantation. Transplant Proc (2018). 50(7):1939–45. 10.1016/j.transproceed.2018.03.128

53.

Sağiroğlu M Günay O Balci E . Attitudes of Turkish Medical and Law Students towards the Organ Donation. Int J Organ Transpl Med (2015). 6(1):1–7.

54.

Sahin H Abbasoglu O . Attitudes of Medical Students from Different Countries about Organ Donation. Exp Clin Transpl (2015). 1–9. 10.6002/ect.2014.0228

55.

Sampaio JE Fernandes DE Kirsztajn GM . Knowledge of Medical Students on Organ Donation. Rev Assoc Med Bras (2020). 66(9):1264–9. 10.1590/1806-9282.66.9.1264

56.

Sanavi S Afshar R Lotfizadeh AR Davati A . Survey of Medical Students of Shahed University in Iran about Attitude and Willingness toward Organ Transplantation. Transplant Proc (2009). 41(5):1477–9. 10.1016/j.transproceed.2009.01.080

57.

Sayedalamin Z Imran M Almutairi O Lamfon M Alnawwar M Baig M . Awareness and Attitudes towards Organ Donation Among Medical Students at King Abdulaziz University, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. J Pak Med Assoc (2017). 67(4):534–7.

58.

Sebastián-Ruiz MJ Guerra-Sáenz EK Vargas-Yamanaka AK Barboza-Quintana O Ríos-Zambudio A García-Cabello R et al Knowledge and Attitude towards Organ Donation of Medicine Students of a Northwestern Mexico Public university. Gac Med Mex (2017). 153(4):430–40. 10.24875/gmm.17002573

59.

Tagizadieh A Shahsavari Nia K Moharamzadeh P Pouraghaei M Ghavidel A Parsian Z et al Attitude and Knowledge of Medical Students of Tabriz University of Medical Sciences Regarding Organ Donation. Transplant Proc (2018). 50(10):2966–70. 10.1016/j.transproceed.2017.12.057

60.

Tuesca R Navarro E Camargo R . Conocimientos y actitudes de los estudiantes de medicina de instituciones de educación superior de Barranquillla sobre donación y trasplante. Salud Uninorte (2002). 16:19–29.

61.

Tumin M Tafran K Tang LY Chong MC Mohd Jaafar NI Mohd Satar N et al Factors Associated with Medical and Nursing Students' Willingness to Donate Organs. Med (2016). 95(12):e3178–4. 10.1097/MD.0000000000003178

62.

Verma M Sharma P Ranjan S Sahoo SS Aggarwal R Mehta K et al The Perspective of Our Future Doctors Towards Organ Donation: A National Representative Study From India. Int J Adolesc Med Health (2020). 10.1515/ijamh-2020-0041

63.

Wu X Gao S Guo Y . Attitude of Students in Shanghai University of Traditional Chinese Medicine toward Donation after Cardiac Death. Transplant Proc (2020). 52(3):700–5. 10.1016/j.transproceed.2019.12.036

64.

Zahmatkeshan M Fallahzadeh E Moghtaderi M Najib K-S Farjadian S . Attitudes of Medical Students and Staff toward Organ Donation in Cases of Brain Death: A Survey at Shiraz University of Medical Sciences. Prog Transpl (2014). 24(1):91–6. 10.7182/pit2014248

65.

Zhang L Liu W Xie S Wang X Mu-Lian Woo S Miller AR et al Factors behind Negative Attitudes toward Cadaveric Organ Donation: A Comparison between Medical and Non-medical Students in China. Transplant (2014). Publish Ahead of Print. 10.1097/tp.0000000000000163

66.

Von Elm E Altman DG Egger M Pocock SJ Gøtzsche PC Vandenbroucke JP . The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) Statement: Guidelines for Reporting Observational Studies. Bull World Health Organ (2007). 85(11):867–72. 10.2471/BLT.07.045120

67.

Borenstein M Hedges LV Higgins JP Rothstein HR . Introduction to Meta-Analysis. Chichester, UK: Wiley (2011).

68.

Duval S Tweedie R . Trim and Fill: A Simple Funnel-Plot-Based Method of Testing and Adjusting for Publication Bias in Meta-Analysis. Biometrics (2000). 56(2):455–63. 10.1111/j.0006-341X.2000.00455.x

69.

Borenstein M Hedges LV Higgins J Rothstein HR . Comprehensive Meta-Analysis 2.0. Englewood, NJ: Biostat (2005).

70.

Ebony Boulware L Ratner LE Ann Sosa J Cooper LA LaVeist TA Powe NR . Determinants of Willingness to Donate Living Related and Cadaveric Organs: Identifying Opportunities for Intervention. Transplantation (2002). 73(10):1683–91. 10.1097/00007890-200205270-00029

71.

Conesa C Ríos A Ramírez P Rodríguez MM Rivas P Canteras M et al Psychosocial Profile in Favor of Organ Donation. Transplant Proc (2003). 35(4):1276–81. 10.1016/S0041-1345(03)00468-8

72.

Vijayalakshmi P Sunitha TS Gandhi S Thimmaiah R Math SB . Knowledge, Attitude and Behaviour of the General Population towards Organ Donation: An Indian Perspective. Natl Med J India (2016). 29(5):257–61.

73.

Mikla M Rios A Lopez-Navas A Gotlib J Kilanska D Martinez-Alarcón L et al Factors Affecting Attitude toward Organ Donation Among Nursing Students in Warsaw, Poland. Transplant Proc (2015). 47(9):2590–2. 10.1016/j.transproceed.2015.09.031

74.

McGlade D McClenahan C Pierscionek B . Pro-Donation Behaviours of Nursing Students from the Four Countries of the UK. PLoS ONE (2014). 9(3):e91405–6. 10.1371/journal.pone.0091405

75.

Li MT Hillyer GC Husain SA Mohan S . Cultural Barriers to Organ Donation Among Chinese and Korean Individuals in the United States: A Systematic Review. Transpl Int (2019). 32(10):1001–18. 10.1111/tri.13439

76.

Fontana F Massari M Giovannini L Alfano G Cappelli G . Knowledge and Attitudes toward Organ Donation in Health Care Undergraduate Students in Italy. Transplant Proc (2017). 49(9):1982–7. 10.1016/j.transproceed.2017.09.029

77.

Global Observatory on Donation and Transplantation (GODT) (2022). Available from: http://www.transplant-observatory.org/.

78.

Conesa C Ríos A Ramírez P del Mar Rodríguez M Rivas P Parrilla P . Socio-personal Factors Influencing Public Attitude towards Living Donation in South-Eastern Spain. Nephrol Dial Transplant (2004). 19(11):2874–82. 10.1093/ndt/gfh466

79.

Hakeem AR Ramesh V Sapkota P Priya G Rammohan A Narasimhan G et al Enlightening Young Minds: A Small Step in the Curriculum, a Giant Leap in Organ Donation-A Survey of 996 Respondents on Organ Donation and Transplantation. Transplantation (2021). 105(3):459–63. 10.1097/TP.0000000000003403

80.

Lei L Lin L Deng J Dong H Luo Y . Developing an Organ Donation Curriculum for Medical Undergraduates in China Based on Theory of Planned Behavior: A Delphi Method Study. Ann Transpl (2020). 25:e922809. 10.12659/AOT.922809

Summary

Keywords

meta-analysis, willingness, medical students, organ donation, cultural

Citation

Iniesta-Sepúlveda M, López-Navas AI, Gutiérrez PR, Ramírez P and Ríos A (2022) The Willingness to Donate Organs in Medical Students From an International Perspective: A Meta-Analysis. Transpl Int 35:10446. doi: 10.3389/ti.2022.10446

Received

21 February 2022

Accepted

17 May 2022

Published

28 June 2022

Volume

35 - 2022

Updates

Copyright

© 2022 Iniesta-Sepúlveda, López-Navas, Gutiérrez, Ramírez and Ríos.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Antonio Ríos, arzrios@um.es

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.