Abstract

The growing number of organ donors in the United States, from 14,011 in 2012 to 21,374 in 2022, highlights progress in addressing the critical issue of organ shortages. However, the demand remains high, with 17 patients dying daily while on the waiting list. As of August 2023, over 103,544 individuals are awaiting transplants, predominantly for kidneys (85.7%). To expand the donor pool, the inclusion of elderly donors, including those with a history of malignancies, is increasingly considered. In 2022, 7% of all donors were aged 65 and above, despite the complexities their medical histories may introduce, particularly the risk of donor-transmitted cancer (DTC). This review examines the challenges and potential benefits of using donors with known malignancy histories, balancing the risks of DTC against the urgency for transplants. A critical analysis is presented on current knowledge and the decision-making processes that consider cancer types, stages, and patient survival outcomes. The goal is to identify missed opportunities and improve strategies for safe and effective organ transplantation from this donor demographic.

Introduction

Over the past few years there has been consistent growth in the number of organ donors with numbers rising from 14,011 donors in 2012 to 21,374 in 2022 in the United States [1, 2]. However, the problem of organ shortage remains a significant challenge with 17 patients on the waiting list losing their lives daily due to the unavailability of suitable organs [1, 2].

As of August 2023, the number of patients on the organ transplant waiting list reached 103,544 individuals [2]. Among the organ types, the kidney is the most prevalent, accounting for 85.7% of the patients, followed by those in need of a liver (9.8%), heart (3.2%), lung (0.9%), and other organs (0.4%) [2]. To address this critical need, there were 6,466 living donors and 14,903 deceased donors, totaling 21,369 individuals who donated organs. In 2022 alone, a total of 42,880 successful organ transplants were performed [1, 2].

As life expectancy continues to rise, a growing number of elderly patients appear as potential organ donors due to the necessity to increase the organ donor pool, even with marginal donors [3]. In 2022, 7% of all donors had 65+ years, the highest percentage ever [4]. However, this demographic often carries a history of comorbidities, including malignancies, which adds complexity to an already risk full procedure [5, 6]. One of the significant concerns is the possibility of transmitting diseases or malignancies from the donor to the recipient [7].

Donors with a history of cancer, the main focus of this review, are individuals who have been previously diagnosed and treated for malignancy, but whose cancer is considered cured or in remission at the time of organ donation. In contrast, donors with a known tumor prior to organ procurement or detected during procurement are individuals where the malignancy, such as renal cell carcinoma (RCC) or certain brain tumors, is actively identified either in pre-donation evaluations or during the retrieval process, raising immediate considerations for recipient safety and donor eligibility. Finally, donors with unknown or undetected tumors at the time of transplantation represent a distinct category, as these malignancies, such as malignant melanoma, are discovered only post-transplantation, often in the recipient, posing significant challenges in terms of retrospective diagnosis and management of transmitted cancer. These categories highlight the varying levels of risk and clinical decision-making required in the evaluation and use of organs from donors with malignancy-related considerations.

Even among donors with previous malignancy history, there are substantial differences in the risks [8–14]. Weighing the risks associated with donor-transmitted cancer (DTC) against the probability of a patient dying while waiting for a donation is a delicate and complex decision [15]. Clinical assessment, considering various factors such as the type and stage of cancer, as well as patient survival on the waiting list, is essential in determining the feasibility and safety of organ transplantation in such cases [8–14]. Even with optimal donor evaluation, there remains an inherent risk of tumor transmission, particularly as donor age increases, due to the higher likelihood of undetected or subclinical malignancies in older individuals.

This review will focus on known malignancy history to gather and present the most up-to-date knowledge about donor-transmitted cancer and critically analyze potential missed opportunities.

Assessment of Transmission Risk

Reported rates of donor-derived cancer transmission to organ recipients vary significantly, ranging from 0 to 42 percent, depending on the data source [8, 9, 13, 16–18]. These high variations could be explained by older data relying on voluntary reporting of index cases and may, therefore, be prone to overestimation [11, 13, 14].

While the exact risk of transmitting any specific cancer from the donor to the recipient is often uncertain, it is possible to broadly assess the likelihood of transmission based on available knowledge regarding the cancer type, its stage, metastatic potential, and recurrence patterns in both transplant and non-transplant settings. Table 1 summarizes the main cancer types and stages and was prepared based on the most recent guidelines [8–14, 20].

TABLE 1

| Risk classification categories | |

| Minimal risk of transmission (<0.1%) – Likely to be acceptable for all organ types and recipients | |

| Low risk of transmission (0.1% to <2%) – Likely to be acceptable for many organ types and recipients | |

| High risk of transmission (≥10%) – May be acceptable in exceptional circumstances | |

| Unacceptable risk – Use of organs is not recommended in any circumstance | |

| Breast cancer | ||||

| Ductal carcinoma in situ | ||||

| Stage Ia hormone-negative breast cancer, >5 years cancer free | ||||

| Stage Ib or higher hormone receptor-positive breast cancer | ||||

| Breast cancer diagnosed at retrieval | ||||

| Central nervous system Tumors (see Table 2 for more information) | ||||

| Primary brain tumors | ||||

| Secondary brain tumors Cerebral lymphoma |

||||

| Colorectal Carcinoma | ||||

| Carcinoma in situ of the colon or rectum | ||||

| Treated Stage I colorectal cancer (N0/M0), >5 years cancer free (except familial adenomatous polyposis) | ||||

| Stage I colorectal cancer diagnosed during retrieval Stage IIa colorectal cancer, >10 years cancer free |

||||

| Stage II or higher colorectal cancer with ≤10 years cancer free | ||||

| Renal Cell Carcinoma | ||||

| Renal cell carcinoma <1 cm, Fuhrman Grade I-II | ||||

| Renal cell carcinoma >1 and ≤4 cm, Fuhrman Grade I-II | ||||

| Renal cell carcinoma >4–7 cm, Fuhrman Grade I-II | ||||

| Renal cell carcinoma with extra-renal extension or Fuhrman Grade III-IV | ||||

| Lung Cancer | ||||

| In situ lung cancer | ||||

| Any history of metastatic lung cancer | ||||

| Prostate Adenocarcinoma | ||||

| Prostate cancer with Gleason score ≤6 or treated with Gleason score 7 | ||||

| Recently diagnosed prostate cancer with Gleason score 7 | ||||

| Prostate cancer with distant metastasis | ||||

| Skin Cancers | ||||

| In situ cutaneous melanoma In situ squamous cell carcinoma Basal cell carcinoma |

||||

| Cutaneous melanoma ≤0.8 mm (T1/N0/M0) completely resected or >0.8 mm (T2-T4/N0/M0) with >10 years cancer free | ||||

| Invasive cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma with nodal involvement or metastasis Cutaneous melanoma T2-T4 with ≤10 years cancer free with nodal involvement or metastasis Uveal or mucosal melanoma |

||||

| Thyroid Cancers | ||||

| Papillary thyroid microcarcinoma Differentiated thyroid tumors ≤4 cm limited to the thyroid (T1/T2) |

||||

| Newly diagnosed differentiated thyroid cancer >4 cm (T3, M0) or with extensive spread (T4), treated and ≥2 years cancer free | ||||

| Thyroid lymphomas, thyroid sarcomas, and other rare tumors of the thyroid Treated thyroid cancer with incomplete macroscopic tumor resection |

||||

| Others | ||||

| Choriocarcinoma | ||||

Risk assessment of major cancer types.

Table 1 was built using the most recent guidelines around the world, including from the European Committee on Organ Transplantation, the Transplantation Society of Australia and New Zealand (TSANZ), the Advisory Committee on the Safety of Blood, Tissues, and Organs (SaBTO) of the UK Government. Guidelines from the USA, spain, and Italy were also included [9–15, 19].

Primary Brain Tumors

Primary solid central nervous system (CNS) tumors may occasionally lead to death in circumstances where organ donation is possible [19]. Extracranial spread of brain tumors is rare, though there are reports of malignancy transmission to the recipients of organs from such donors [21–31].

Primary brain tumors are graded by the World Health Organization (WHO) from grade I to grade IV based on their biological behavior and prognosis [32]. Grade IV tumors are considered cytologically malignant and generally fatal, leading to the perception that they pose the highest risk of transmitting malignancy from donor to recipient [32]. However, several cases of organ transplants from donors with grade IV tumors have been reported without the transmission of malignancy to the recipients [19, 33].

For instance, a UK review of 448 recipients who received organs from 177 donors with primary CNS tumors, including 23 donors with grade IV gliomas and 9 with medulloblastoma, found no evidence of tumor transmission over a minimum follow-up period of 5 years [34]. Similarly, an Australian and New Zealand registry review of 46 donors (9 with high-grade tumors) who provided organs to 153 recipients did not identify any transmission events [35].

Another report from the United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS) database, which included 642 recipients of organs from donors with CNS tumors, including 175 recipients from donors with high-grade tumors, documented a single case of disease transmission from a donor with glioblastoma multiforme to three recipients [25, 36]. Finally, in a Czech report of 42 donors (11 with high-grade tumors), no transmission was observed among 88 recipients monitored for 2–14 years [37].

A more recent study also from the UK had a 10-year survival of transplants from donors with brain tumors of 65% (95% CI, 59%–71%) for single kidney transplants, 69% (95% CI, 60%–76%) for liver transplants, 73% (95% CI, 59%–83%) for heart transplants, and 46% (95% CI, 29%–61%) for lung transplants [19] which stays in proximity with UNOS national average without malignancy [38–41] (Figure 1). For example, kidney had a 78.15% (95%CI, 73.5%–82.7%) 10-year survival, liver had a 64.1%, heart had a 5-year survival of 80% and lung transplants had a 32.8% survival in 10 years [38–41].

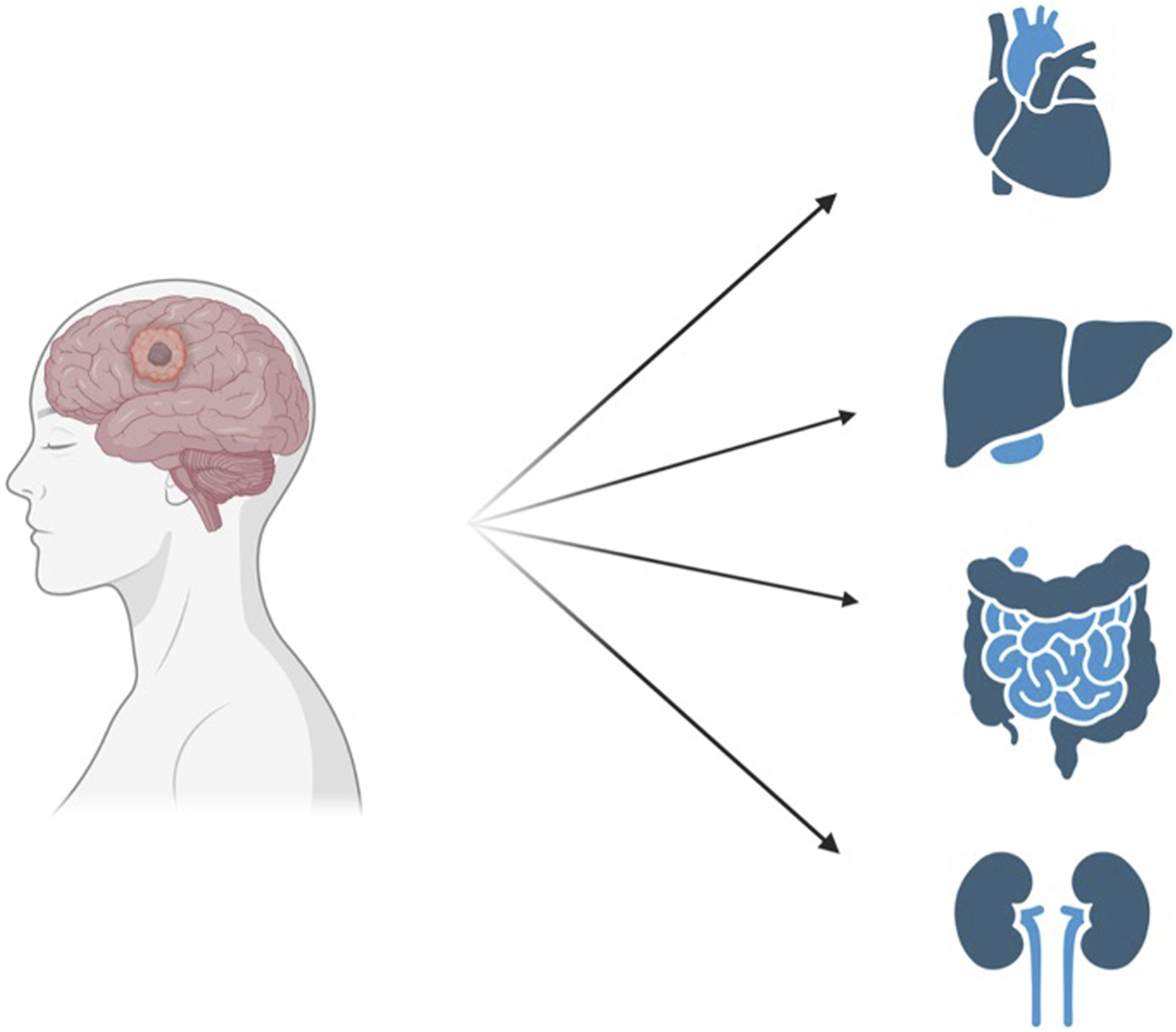

FIGURE 1

The still unexplored use of donors with previous malignancies can greatly contribute to an increase in the organ pool. Created with BioRender.com.

Overall, The UK’s Advisory Committee on the Safety of Blood, Tissues, and Organs (SaBTO) [11] estimates the risk of tumor transmission from WHO grade I and II tumors to be minimal (<0.1%), the risk from grade III tumors to be low (0.1 to <2%) and the risk of transmission from grade IV tumors as 2.2% [10].

Subsequent reports, where WHO grading was adopted, have suggested that the risk of transmission is much lower [33–37, 42]. Of >77 donors with grade 4 CNS tumors donating to >338 recipients (>34 liver recipients), there was only one that transmitted cancer, with three recipients affected [25, 36]. Despite these favorable registry reports, there have been cases of CNS tumor transmission, including 6 in LT recipients [22, 23, 25, 27, 29, 31, 43–45].

In addition to the reported risks, other factors show clinical significance pertaining to CNS malignancy transmission. Interventions such as brain irradiation, chemotherapy, previous craniotomy, and ventriculoperitoneal shunt procedures may increase the risk of transmitting CNS malignancy from donors to recipients [11, 43, 46]. These interventions potentially breach the blood-brain barrier, facilitating tumor spread. However, it is challenging to differentiate between causality and coincidence. It is possible that certain interventions are more commonly employed in tumors that are more prone to spreading.

One important factor is that the presence of brain metastases can sometimes be incorrectly diagnosed as primary CNS tumors or intracranial hemorrhage, and organ transplantation from these donors has been associated with a poor prognosis for the recipients [46]. A study involving 42 recipients of organs from patients with misdiagnosed primary CNS tumors revealed that 74% of the recipients developed a malignancy derived from the donor, and 64% developed metastatic disease [46]. The 5-year survival rate for these recipients was only 32% [46]. Therefore, in cases where donors present with unexplained intracranial hemorrhage or suspected primary CNS neoplasm without a biopsy, it is crucial to consider conducting an evaluation specifically for metastatic disease [46].

The risk assessment of CNS cancers, specifically pertaining to organ transplantation shown in Table 2 has been conducted by utilizing the recommendations provided by the Advisory Committee on the Safety of Blood, Tissues, and Organs (SaBTO) [10] and the UNOS recommendations [11]. These assessments have incorporated findings from the SaBTO report, and the outcomes of more recent studies conducted, including those within the United Kingdom [19, 34, 47]. This led to a revised understanding of the risks associated with CNS tumors, but still deficient in quantity and quality of evidence.

TABLE 2

| Absolute contraindications |

| • Primary cerebral lymphoma • All secondary intracranial tumors • Any cancer with metastatic spread |

| Intracranial tumors with Intermediate risk of cancer transmission (2.2%) include WHO Grade 4 tumors |

| • Atypical teratoid/rhabdoid tumor • Choriocarcinoma • Diffuse midline glioma, H3K27 M-mutant • Embryonal tumor (all subtypes) • Giant cell glioblastoma (old classification) • Glioblastoma (IDH wild type and IDH mutant) • Gliosarcoma • Malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor (MPNST) – grade 4 • Medulloblastoma • Medulloepithelioma • Pineoblastoma |

| Intracranial tumors with a lower risk of cancer transmission (<2%) include WHO Grade 3 tumors |

| • Anaplastic CNS tumors • Choroid plexus carcinoma • Ependymoma: RELA fusion-positive • Haemangiopericytoma/solitary fibrous tumor • Papillary tumor of the pineal region • Pineal parenchymal tumor of intermediate differentiation • Malignant peripheral sheath tumor grade 3 |

| Intracranial tumors with minimal risk of cancer transmission (<0.1%) |

| • Low-grade CNS tumor (WHO grade I or II) • Primary CNS mature teratoma |

Risk assessment of CNS tumors.

The risk assessment of CNS cancers, specifically pertaining to organ transplantation shown in Table 2 has been conducted by utilizing the recommendations provided by the Advisory Committee on the Safety of Blood, Tissues, and Organs (SaBTO) [10] and the UNOS recommendations [11]. These assessments have incorporated findings from the SaBTO report, and the outcomes of more recent studies conducted [19, 34, 47].

Breast Cancer

Breast cancer is the most frequent cancer in females and is associated with the highest mortality [48]. Organs from donors with a history of invasive breast cancer should only be considered when a low risk of transmission criteria is observed because of the potential for metastasis and late recurrence [49, 50]. A history of Stage I, T1A, node-negative, hormone receptor-negative breast cancer may still be viable in a donor that has had full treatment and complete remission with follow-up >5 years [51]. Any other type of invasive breast cancer is considered a high risk (>10%) of malignancy transmission, regardless of the disease-free interval [13].

Hormone-positive breast cancer poses a high cumulative risk of recurrence at 20 years post-treatment [49, 50]. Given this fact, donors with this type of cancer have a high transmission risk [9]. Lobular breast cancer and ductal carcinoma provide a similar risk of recurrence [52], so it is possible to group them together under Stage I breast cancer with >5 years of recurrence-free survival for risk assessment. In the event of a known history of invasive breast cancer but insufficient data, either pathologic or clinical, donation should only be considered for recipients facing an imminent threat to life [9]. Invasive breast cancer diagnosed during retrieval poses an unacceptable risk to potential transplant recipients [13].

Renal Carcinoma

Literature shows documentation of successful kidney transplantation after renal cell carcinoma resection for tumors <4 cm detected at organ retrieval [53–55]. In one study following 21 kidneys with tumors from 0.1 to 2.1 cm, as well as 47 contralateral kidneys and 198 non-renal organs, no cases of malignancy transmission were identified [53]. Another study showed no cases of transmission in 97 kidney transplantations after RCC resection <4 cm, although there was one case in the transplant of 22 contralateral kidneys [54]. In the case of well-differentiated RCC, the risk of transmission was assessed as minimal (<0.1%) in tumors ≤1.0 cm in size, or low (<2%) for tumors >1.0 cm to ≤4 cm in size [10]. Therefore, all organs are considered for transplantation, including the affected kidney, after resection on as RCC <4 cm with Fuhrman grade I-II, when satisfactory margins are achieved [10, 11, 56]. Outside of organ retrieval, if RCC diagnosis was less than 5 years before organ donation, the same risks for RCC diagnosed during organ retrieval apply. For patients with RCC >5 years with appropriate follow-up, theoretical risks may be even lower [9]. Donors with RCC 4–7 cm with Fuhrman I-II, with higher than 5 years cancer-free interval may be considered for non-renal organs [57] Any history of invasive RCC or Fuhrman grade III-IV represents an unacceptable risk [13].

Primary Liver Tumors

Liver, biliary, or pancreatic cancers that are diagnosed during organ retrieval provide an unacceptable risk of malignancy transmission in organ transplantation [9]. Even if identified in treated history, they are usually also considered unacceptable risks given the aggressive nature and high recurrence of these cancers [9].

However, benign liver tumors are relatively common, occurring in up to 20% of the general population [58] the most frequent lesions being hepatic hemangioma (HH), focal nodular hyperplasia (FNH), and hepatocellular adenoma (HCA and are safe to transplant, so it’s essential to differentiate between a tumor is malignant before ruling out donation [58, 59]. Some studies exist showing cancer transmission in liver, biliary, or pancreatic cancer [42, 60–63].

Malignant Melanoma

Melanoma of the skin represents 5% of all new cancer cases in the US [64]. Melanoma is known for its potential transmission from donor to recipient during transplantation [36, 65–68] particularly pronounced when the diagnosis is overlooked in the donor, leading to significant implications [36, 57, 69–73]. The prevalence of melanoma as a tumor type is high, marked by early micro metastasis and the inherent challenge of detection [74, 75]. Invasive melanoma constitutes around 30% of reported cases of donor-related cancers [18, 76] with fatal consequences, as it correlates with a high recipient mortality rate, estimated at approximately 60% [7]. The level of risk associated with the transmission of cutaneous melanoma hinges on factors like Breslow thickness and the stage of melanoma at the time of diagnosis and treatment [77]. Notably, in situ cutaneous melanoma, being non-invasive, presents minimal chances of donor-derived transmission due to the absence of metastatic risk associated [65, 78, 79].

Invasive cutaneous melanoma is considered a high to unacceptable risk of transmission as it may recur regardless of many years of disease-free interval and poses a theoretically higher threat on immunosuppressed patients, given that on non-immunosuppressed individuals, the lifetime risk of recurrence is greater than 2% for T1a (<0.8 mm thickness) and greater than 10% in T1b (0.9–1.0 mm) [80–82]. Another hazard of melanoma is its spread to distant sites, even during the early stages of the disease, with cells that may stay dormant and undetectable for many years after primary resection [83]. If transplanted, these cells may lead to metastatic growth in an immunosuppressed patient [66, 84–86], with high mortality rates [87, 88]. Similarly, uveal and mucosal melanoma pose an unacceptable risk to donation, given a high risk of undetected micro metastases, regardless of the length of disease-free survival, as does cutaneous melanoma with a history of nodal involvement or distant metastases [89–91].

Considering all these factors, there are instances where organs from donors with melanoma, other than in situ, may be used under exceptional life-or-death circumstances [13]. As always, this decision must be based on a thorough assessment of risk status, with ample information available, and always accompanied by the informed consent of the recipient.

Prostate Cancer

Prostate cancer provides a minimal-to-low risk of malignancy transmission given, as with many other types of cancer, its confinement to the original organ [92]. It is one of the most prevalent cancers accounting for 14.7% of all new cancer cases in the U.S. In 2023, there were an estimated 4,956,901 men living with prostate cancer in the World [48, 93]. A study conducted on organ donors showed that 23% of those aged 50–59 years, 35% of those aged 60–69, and 46% of those aged 70–81 years had undiagnosed prostate cancer [94]. However, there was no evidence of higher prevalence of prostate cancer among transplant recipients relative to the general male population [95, 96].

The Gleason score is a valuable tool when deciding to proceed with the donation [97, 98]. A Gleason score of 6 provides an almost-zero risk of transmission [99]. A donor with a history of a Gleason 7 prostate cancer may also be considered minimal risk, provided the tumor was organ-confined and the donor has been cancer-free for more than 3 years [92, 100]. Analyzing 120 reports of transplants coming from donors with confirmed prostate cancer, only one case was identified [101], and that came from a donor later found to have metastatic disease [102]. A meta-analysis concluded that the risk of remaining on the waiting list was higher than the risk of transmission in transplants with a donor with prostate cancer [92].

Primary Lung Carcinoma

There are registry and case reports of occult donor transmission with kidney transplantation, highly fatal outcomes, and very aggressive behavior from donor-transmitted lung cancer [57, 103–105]. Benign pulmonary nodules – such as hamartomas and papillomas – are relatively common, especially after 45 years of age and account for more than 95% of all pulmonary nodules [106]; hence it is important to distinguish between benign tumors in the lung and lung cancer in the donor.

Transmission of lung cancer to liver transplant recipients has been reported with fatal consequences in 2 cases, including 1 undergoing urgent transplantation when the adenocarcinoma was found on donor autopsy [107, 108]. There are also reports of transmission in several registry studies [17, 18, 20, 60, 69, 109]. In contrast, there are a few reports of donor lung cancer not being transmitted to liver transplant recipients [17, 20, 110]. Still, lung cancer at any stage (excluding in situ – high risk) [13] is considered an unacceptable risk [9, 13].

Colorectal Cancer

Colorectal cancer is common in the population and a common cause of mortality [48]. The liver is the most frequent site of metastasis [111]. A 2003 US consensus agreed on the use of Stage I – T1, node-negative – colorectal cancer individuals as organ donors given the low risk of nodal or metastatic disease associated [112]. For individuals with Stage I familial adenomatous polyposis who are potential donors, caution should be exercised when considering pancreas transplantation due to an elevated risk of duodenal cancers [13]. However, under specific circumstances and clinical assessment, transplantation of certain other organs might still be viable [9]. In cases where Stage II or higher colorectal cancer is detected either during retrieval or in the donor’s medical history, with a cancer-free period of up to 10 years, the potential for transmitting cancer to recipients is deemed unacceptable [11, 13].

However some more recent studies suggest the risk might be lower [110, 113]. As new forms of cancer targeting appear [114] and recently showed that patients with this type of cancer may have a good prognosis [115, 116] with effective surveillance [117], new data on colorectal cancer and its safety should appear in the following years. It is important that pathology reports are made available to accurately determine the stage of cancer before proceeding with transplantation. During retrieval procedures, surgeons should meticulously inspect all intra-abdominal and intra-thoracic structures for any suspicious lesions [15, 109].

Thyroid Tumors

Approximately 90% of thyroid cancers are either papillary (80%) or follicular (10%) [118], usually with only localized spread [48]. The relative survival rate is 97% in a 5-year interval, if not in advanced stages [48, 119]. Distant metastases develop in 5%–23% of differentiated thyroid cancers, typically in the lungs and bones [120]. Post-operative risk of recurrence after tumor resection is low when the tumor does not have aggressive histology [121].

The risk of malignancy transmission in differentiated thyroid cancer varies depending on the size of the tumor and the spread, with cancers up to 4 cm providing a minimal risk of transmission if confined to the thyroid, even if only detected at organ retrieval [9, 11, 13]. On an important note, thyroid cancers are not affected by immunosuppression, which means that pre-existing thyroid cancers do not show increased rates of progression, and the incidence of thyroid cancer is not elevated in recipients [96, 122]. Additionally, even in the event of donor-derived transmission, metastatic differentiated thyroid cancer can still be treated with curative therapy, depending on histology [120].

Other Cancers

While the main cancers associated with organ donation are well-documented, consideration should also be given to other less commonly reported malignancies, such as ovarian, cervical, and pancreatic cancers. These malignancies pose unique challenges due to their aggressive nature and potential for microscopic metastases. However, the current literature lacks sufficient data to assess the transmission risks or to establish evidence-based recommendations for the utilization of organs from donors with these types of cancers. As such, further studies and case reports are needed to better understand the risks and outcomes associated with these malignancies in the context of organ transplantation.

Discussion

History of malignancy or, in some cases, an active malignant disease in the potential donor should not automatically be a veto to organ donation. The estimated risk of tumor transmission should be balanced against the benefit of the transplant for recipients. Donor-transmitted cancer is still an area to be better understood, with few quality studies showing varied results that could either underestimate or overestimate the probability of developing DTC [123–125].

As the donor waiting lists continue to rise and general life expectancy tends to get older, reevaluating the risk of DTC could provide a powerful ally in increasing the donor pool, with many more donors becoming available. Currently, there is still a feeling of missed opportunities in perceived high-risk transplants that retrospectively have not shown the same risk, especially regarding CNS tumors [126], that’s have historically been put in a >10% risk category [11] and are now reduced to a 2.2% risk [8–10, 13]. There is expectation concerning what other risk reductions are viable, but more detailed data, including reliable reporting of transmission events, is necessary to include, as of now, high-risk malignancies in a potential donor list and to allow a more evidence-based decision process.

The frequently urgent nature of organ transplantation often precludes the possibility of obtaining all of the desired information, and the physician must weigh available clinical data and published experience along with the medical condition and desires of the patient in arriving at the best possible decision. Although a certain transmission risk will remain in many cases, selected patients will benefit from these organs more than if they stayed on the waiting list.

It is important to notice, however, that even without a prior history of neoplasm, there is still a chance of donor-origin cancer (DOC) of 0.06%, as it was concluded by a study with 30,765 transplants conducted in the UK [17]. In this study of the 18 recipients who developed DOC from 16 donors (0.06%): 3 were DDC (donor-derived cancer - posterior growth of malignancy after transplantation, derived from donor cells), and 15 were DTC (donor-transmitted cancer). Of the 15 DTCs, 6 were renal cell cancer; 5 lung cancer; 2 lymphoma; 1 neuroendocrine cancer; and 1 colon cancer. This represented an unavoidable, but low risk of DOC in every transplant made [17], which should be taken into consideration when weighing the risks.

Noticeably, no guidelines exist on retransplantation in DTC events. Decisions should be made on a case-by-case basis with a multidisciplinary approach and after discussion with the patient or relatives. Retransplantation may be reasonably considered when the tumor identified in the donor is deemed of intermediate or high risk of transmission.

Conclusion

An individualized clinical judgment for using organs from donors with malignancy should be made and presented to the recipients, including the risk of not proceeding with transplantation, with fully informed consent being mandatory where the risks are higher than standard expectations.

This review stands to bring back the focus on DTC, urging for a more extensive evidence base providing more accurate and clinically relevant recommendations to aid the patient’s physician in a more secure clinical decision, as well as providing an answer to an ever-higher donor waiting list.

Statements

Author contributions

Conceptualization of the study was done by JM, PA, and RV; VT, JM, SR, SZ, and RF participated in writing the original draft; GG, KC, TN, AL, PA, and RV participated in reviewing and editing the manuscript. PA supervised the project, which was administered by VT. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

1.

OPTN. Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network (OPTN) Metrics (2023). Available from: https://insights.unos.org/OPTN-metrics/ (Accessed October 10, 2023).

2.

Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA). Organ Donation Statistics | Organonor.Gov (2024). Available from: https://www.organdonor.gov/learn/organ-donation-statistics (Accessed February 04, 2024).

3.

Goldaracena N Cullen JM Kim DS Ekser B Halazun KJ . Expanding the Donor Pool for Liver Transplantation With Marginal Donors. Int J Surg (2020) 82:30–5. 10.1016/j.ijsu.2020.05.024

4.

OPTN. National Data (2023). Available from: https://optn.transplant.hrsa.gov/data/view-data-reports/national-data/ (Accessed October 11, 2023).

5.

Kovac D Choe J Liu E Scheffert J Hedvat J Anamisis A et al Immunosuppression Considerations in Simultaneous Organ Transplant. Pharmacotherapy (2021) 41(1):59–76. 10.1002/phar.2495

6.

Scheuher C . A Review of Organ Transplantation: Heart, Lung, Kidney, Liver, and Simultaneous Liver-Kidney. Crit Care Nurs Q (2016) 39:199–206. 10.1097/CNQ.0000000000000115

7.

Buell JF Beebe TM Trofe J Gross TG Alloway RR Hanaway MJ et al Donor Transmitted Malignancies. Ann Transpl (2004) 9(1):53–6.

8.

European Committee on Organ Transplantation. European Directorate for the Quality of Medicines and HealthCare. Guide to the Quality and Safety of Organs for Transplantation. In: European Committee on Organ Transplantation. European Directorate for the Quality of Medicines and HealthCare. 8th ed (2022).

9.

Clinical Guidelines for Organ Transplantations From Deceased Donors. The Transplantation Society of Australia and New Zealand TSANZ (2023). https://tsanz.com.au/storage/documents/TSANZ_Clinical_Guidelines_Version-111_13062023Final-Version.pdf.

10.

Transplantation of Organs From Deceased Donors With Cancer or a History of Cancer. Advisory Committee on the Safety of Blood, Tissues and Organs (SaBTO). UK Government Department of Healthx: London, UK (2014).

11.

Nalesnik MA Woodle ES Dimaio JM Vasudev B Teperman LW Covington S et al Donor-transmitted Malignancies in Organ Transplantation: Assessment of Clinical Risk. Am J Transplant (2011) 11:1140–7. 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2011.03565.x

12.

Mahíllo B Martín S Molano E Navarro A Castro P Pont T et al Malignancies in Deceased Organ Donors: The Spanish Experience. Transplantation (2022) 106(9):1814–23. 10.1097/TP.0000000000004117

13.

Domínguez-Gil B Moench K Watson C Serrano MT Hibi T Asencio JM et al Prevention and Management of Donor-Transmitted Cancer After Liver Transplantation: Guidelines From the ILTS-SETH Consensus Conference. Transplantation (2022) 106(1):e12–e29. 10.1097/TP.0000000000003995

14.

Eccher A Lombardini L Girolami I Puoti F Zaza G Gambaro G et al How Safe Are Organs from Deceased Donors With Neoplasia? The Results of the Italian Transplantation Network. J Nephrol (2019) 32:323–30. 10.1007/s40620-018-00573-z

15.

Buell JF Alloway RR Steve Woodle E . How Can Donors With a Previous Malignancy Be Evaluated?J Hepatol (2006) 45:503–7. 10.1016/j.jhep.2006.07.019

16.

Zhang S Yuan J Li W Ye Q . Organ Transplantation From Donors (Cadaveric or Living) With a History of Malignancy: Review of the Literature. Transplant Rev (2014) 28:169–75. 10.1016/j.trre.2014.06.002

17.

Desai R Collett D Watson CJ Johnson P Evans T Neuberger J . Cancer Transmission From Organ Donors-Unavoidable but Low Risk. Transplantation (2012) 94(12):1200–7. 10.1097/TP.0b013e318272df41

18.

Penn I . Transmission of Cancer From Organ Donors. Ann Transplant : Q Polish Transplant Soc (1997) 2(4):7–12.

19.

Greenhall GHB Rous BA Robb ML Brown C Hardman G Hilton RM et al Organ Transplants From Deceased Donors With Primary Brain Tumors and Risk of Cancer Transmission. JAMA Surg (2023) 158(5):504–13. 10.1001/jamasurg.2022.8419

20.

Kaul DR Vece G Blumberg E La Hoz RM Ison MG Green M et al Ten Years of Donor-Derived Disease: A Report of the Disease Transmission Advisory Committee. Am J Transplant (2021) 21(2):689–702. 10.1111/ajt.16178

21.

Lefrancois N Touraine JL Cantarovich D Cantarovich F Faure JL Dubernard JM et al Transmission of Medulloblastoma from Cadaver Donor to Three Organ Transplant Recipients. Transpl Proc (1987) 19(1 Pt 3):2242.

22.

Frank S Müller J Bonk C Haroske G Schackert HK Schackert G . Transmission of Glioblastoma Multiforme Through Liver Transplantation. Lancet. (1998) 352(9121):31. 10.1016/S0140-6736(98)24027-X

23.

Chen H Shah AS Girgis RE Grossman SA . Transmission of Glioblastoma Multiforme After Bilateral Lung Transplantation. J Clin Oncol (2008) 26(19):3284–5. 10.1200/JCO.2008.16.3543

24.

Val-Bernal F Ruiz JC Cotorruelo JG Arias M . Glioblastoma Multiforme of Donor Origin After Renal Transplantation: Report of a Case. Hum Pathol (1993) 24(11):1256–9. 10.1016/0046-8177(93)90224-5

25.

Armanios MY Grossman SA Yang SC White B Perry A Burger PC et al Transmission of Glioblastoma Multiforme Following Bilateral Lung Transplantation from an Affected Donor: Case Study and Review of the Literature. Neuro Oncol (2004) 6(3):259–63. 10.1215/S1152851703000474

26.

Ruiz JC Cotorruelo JG Tudela V Ullate PG Val-Bernal F De Francisco ALM et al Transmission of Glioblastoma Multiforme to Two Kidney Transplant Recipients From the Same Donor in the Absence of Ventricular Shunt. Transplantation (1993) 55(3):682–3.

27.

Jonas S Bechstein WO Lemmens HP Neuhaus R Thalmann U Neuhaus P . Liver Graft-Transmitted Glioblastoma Multiforme. A Case Report and Experience With 13 Multiorgan Donors Suffering From Primary Cerebral Neoplasia. Transpl Int (1996) 9(4):426–9. 10.1007/BF00335707

28.

Zhao P Strohl A Gonzalez C Fishbein T Rosen-Bronson S Kallakury B et al Donor Transmission of Pineoblastoma in a Two-Yr-Old Male Recipient of a Multivisceral Transplant: A Case Report. Pediatr Transpl (2012) 16(4):E110–4. 10.1111/j.1399-3046.2010.01463.x

29.

Morse JH Turcotte JG Merion RM Campbell DA Burtch GD Lucey MR . Development of a Malignant Tumor in a Liver Transplant Graft Procured From a Donor With a Cerebral Neoplasm. Transplantation (1990) 50(5):875–7. 10.1097/00007890-199011000-00026

30.

Hynes CF Ramakrishnan K Alfares FA Endicott KM Hammond-Jack K Zurakowski D et al Risk of Tumor Transmission after Thoracic Allograft Transplantation From Adult Donors With Central Nervous System Neoplasm—A UNOS Database Study. Clin Transpl (2017) 31(4). 10.1111/ctr.12919

31.

Colquhoun SD Robert ME Shared A Rosenthal JT Millis JM Farmer DG et al Transmission of Cns Malignancy by Organ Transplantation. Transplantation (1994) 57(6):970–4.

32.

Louis DN Perry A Reifenberger G von Deimling A Figarella-Branger D Cavenee WK et al The 2016 World Health Organization Classification of Tumors of the Central Nervous System: A Summary. Acta Neuropathologica (2016) 131:803–20. 10.1007/s00401-016-1545-1

33.

Lee MS Cho WH Ha J Yu ES Jeong YS Oh JS et al Safety of Donation From Brain-Dead Organ Donors With Central Nervous System Tumors: Analysis of Transplantation Outcomes in Korea. Transplantation (2020) 104:460–6. 10.1097/TP.0000000000002994

34.

Watson CJE Roberts R Wright KA Greenberg DC Rous BA Brown CH et al How Safe Is It to Transplant Organs From Deceased Donors With Primary Intracranial Malignancy? An Analysis of UK Registry Data. Am J Transplant (2010) 10(6):1437–44. 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2010.03130.x

35.

Chui AKK Herbertt K Wang LS Kyd G Hodgeman G Verran DJ et al Risk of Tumor Transmission in Transplantation From Donors With Primary Brain Tumors: An Australian and New Zealand Registry Report. In: Transplantation Proceedings (1999).

36.

Kauffman HM Cherikh WS McBride MA Cheng Y Hanto DW . Deceased Donors With a Past History of Malignancy: An Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network/United Network for Organ Sharing Update. Transplantation (2007) 84(2):272–4. 10.1097/01.tp.0000267919.93425.fb

37.

Pokorna E Vítko Š . The Fate of Recipients of Organs From Donors With Diagnosis of Primary Brain Tumor. Transpl Int (2001) 14:346–7. 10.1007/s001470100334

38.

Ghelichi-Ghojogh M Ghaem H Mohammadizadeh F Vali M Ahmed F Hassanipour S et al Graft and Patient Survival Rates in Kidney Transplantation, and Their Associated Factors: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Iranian J Public Health (2021) 50:1555–63. 10.18502/ijph.v50i8.6801

39.

Lung Annual Data Report (2023). Available from: https://srtr.transplant.hrsa.gov/annual_reports/2021/Lung.aspx#fig:LUtx-adult-Dth-all-C. (Accessed: October 11, 2023).

40.

Heart Annual Data Report (2023). Available from: https://srtr.transplant.hrsa.gov/annual_reports/2021/Heart.aspx#fig:HRtx-adult-Dth-all-C.(Accessed: October 11, 2023).

41.

Liver Annual Data Report (2023). Available from: https://srtr.transplant.hrsa.gov/annual_reports/2021/Liver.aspx. (Accessed: October 11, 2023).

42.

Kauffman HM McBride MA Cherikh WS Spain PC Marks WH Roza AM . Transplant Tumor Registry: Donor Related Malignancies. Transplantation (2002) 74(3):358–62. 10.1097/00007890-200208150-00011

43.

Buell JF Trofe J Sethuraman G Hanaway MJ Beebe TM Gross TG et al Donors With Central Nervous System Malignancies: Are They Truly Safe? Transplantation (2003) 76(2):340–3. 10.1097/01.TP.0000076094.64973.D8

44.

NHS Blood and Transplant. Events Investigated for Possible Donor-Derived Transmission of Infections, Malignancies and Other Cases of Interest (2019). Available from: https://nhsbtdbe.blob.core.windows.net/umbraco-assets-corp/24453/30-june-2021-report-events-investigated-for-possible-donor-derived-transmission-of-infections-malignancies-march-2018-march-202.pdf (Accessed on December 30, 2024).

45.

Fatt MA Horton KM Fishman EK . Transmission of Metastatic Glioblastoma Multiforme From Donor to Lung Transplant Recipient. J Comput Assist Tomogr (2008) 32(3):407–9. 10.1097/RCT.0b013e318076b472

46.

Buell JF Gross T Alloway RR Trofe J Woodle ES . Central Nervous System Tumors in Donors: Misdiagnosis Carries a High Morbidity and Mortality. Transplant Proc (2005) 37:583–4. 10.1016/j.transproceed.2004.12.125

47.

Warrens AN Birch R Collett D Daraktchiev M Dark JH Galea G et al Advising Potential Recipients on the Use of Organs From Donors With Primary Central Nervous System Tumors. Transplantation (2012) 93:348–53. 10.1097/TP.0b013e31823f7f47

48.

WHO. WHO Global Cancer Observatory. Cancer today (2023). Available from: https://gco.iarc.fr/today/home (Accessed August, 2023).

49.

Pan H Gray R Braybrooke J Davies C Taylor C McGale P et al 20-Year Risks of Breast-Cancer Recurrence After Stopping Endocrine Therapy at 5 Years. New Engl J Med (2017) 377(19):1836–46. 10.1056/NEJMoa1701830

50.

Gonzalez-Angulo AM Litton JK Broglio KR Meric-Bernstam F Rakkhit R Cardoso F et al High Risk of Recurrence for Patients With Breast Cancer Who Have Human Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor 2-Positive, Node-Negative Tumors 1 Cm or Smaller. J Clin Oncol (2009) 27(34):5700–6. 10.1200/JCO.2009.23.2025

51.

Balkenhol MCA Vreuls W Wauters CAP Mol SJJ van der Laak JAWM Bult P . Histological Subtypes in Triple Negative Breast Cancer Are Associated With Specific Information on Survival. Ann Diagn Pathol (2020) 46:151490. 10.1016/j.anndiagpath.2020.151490

52.

Wang K Zhu GQ Shi Y Li ZY Zhang X Li HY . Long-Term Survival Differences Between T1-2 Invasive Lobular Breast Cancer and Corresponding Ductal Carcinoma After Breast-Conserving Surgery: A Propensity-Scored Matched Longitudinal Cohort Study. Clin Breast Cancer (2019) 19(1):e101–15. 10.1016/j.clbc.2018.10.010

53.

Pavlakis M Michaels MG Tlusty S Turgeon N Vece G Wolfe C et al Renal Cell Carcinoma Suspected at Time of Organ Donation 2008-2016: A Report of the OPTN Ad Hoc Disease Transmission Advisory Committee Registry. Clin Transpl (2019) 33(7):e13597. 10.1111/ctr.13597

54.

Yu N Fu S Fu Z Meng J Xu Z Wang B et al Allotransplanting Donor Kidneys After Resection of a Small Renal Cancer or Contralateral Healthy Kidneys From Cadaveric Donors With Unilateral Renal Cancer: A Systematic Review. Clin Transplant (2014) 28:8–15. 10.1111/ctr.12262

55.

Hevia V Hassan ZR Fraser Taylor C Bruins HM Boissier R Lledo E et al Effectiveness and Harms of Using Kidneys With Small Renal Tumors From Deceased or Living Donors as a Source of Renal Transplantation: A Systematic Review. Eur Urol Focus (2019) 5:508–17. 10.1016/j.euf.2018.01.018

56.

Nicol DL Preston JM Wall DR Griffin AD Campbell SB Isbel NM et al Kidneys From Patients With Small Renal Tumours: A Novel Source of Kidneys for Transplantation. BJU Int (2008) 102(2):188–92. 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2008.07562.x

57.

Eccher A Girolami I Motter JD Marletta S Gambaro G Momo REN et al Donor-transmitted Cancer in Kidney Transplant Recipients: A Systematic Review. J Nephrol (2020) 33(6):1321–32. 10.1007/s40620-020-00775-4

58.

Ostojic A Mrzljak A Mikulic D . Liver Transplantation for Benign Liver Tumors. World J Hepatol (2021) 13(9):1098–106. 10.4254/wjh.v13.i9.1098

59.

Oldhafer KJ Habbel V Horling K Makridis G Wagner KC . Benign Liver Tumors. Visc Med (2020) 36:292–303. 10.1159/000509145

60.

Ison MG Nalesnik MA . An Update on Donor-Derived Disease Transmission in Organ Transplantation. Am J Transplant (2011) 11:1123–30. 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2011.03493.x

61.

Gerstenkorn C Thomusch O . Transmission of a Pancreatic Adenocarcinoma to a Renal Transplant Recipient. Clin Transpl (2003) 17(5):473–6. 10.1034/j.1399-0012.2003.00072.x

62.

Georgieva LA Gielis EM Hellemans R Van Craenenbroeck AH Couttenye MM Abramowicz D et al Single-Center Case Series of Donor-Related Malignancies: Rare Cases With Tremendous Impact. Transpl Proc (2016) 48(8):2669–77. 10.1016/j.transproceed.2016.07.014

63.

Kim B Woreta T Chen PH Limketkai B Singer A Dagher N et al Donor-Transmitted Malignancy in a Liver Transplant Recipient: A Case Report and Review of Literature. Dig Dis Sci (2013) 58:1185–90. 10.1007/s10620-012-2501-0

64.

Melanoma of the Skin — Cancer Stat Facts (2023). Available from: https://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/melan.html (Accessed: October 11, 2023).

65.

Abdullayeva L . Donor-Transmitted Melanoma: Is It Still Bothering Us?Curr Treat Options Oncol (2020) 21:38. 10.1007/s11864-020-00740-0

66.

Strauss DC Thomas JM . Transmission of Donor Melanoma by Organ Transplantation. The Lancet Oncol (2010) 11:790–6. 10.1016/S1470-2045(10)70024-3

67.

Bilal M Eason JD Das K Sylvestre PB Dean AG Vanatta JM . Donor-Derived Metastatic Melanoma in a Liver Transplant Recipient Established by DNA Fingerprinting. Exp Clin Transplant (2013) 11(5):458–63. 10.6002/ect.2012.0243

68.

Park CK Dahlke EJ Fung K Kitchen J Austin PC Rochon PA et al Melanoma Incidence, Stage, and Survival After Solid Organ Transplant: A Population-Based Cohort Study in Ontario, Canada. J Am Acad Dermatol (2020) 83(3):754–61. 10.1016/j.jaad.2019.09.072

69.

Green M Covington S Taranto S Wolfe C Bell W Biggins SW et al Donor-Derived Transmission Events in 2013: A Report of the Organ Procurement Transplant Network Ad Hoc Disease Transmission Advisory Committee. Transplantation (2015) 99(2):282–7. 10.1097/TP.0000000000000584

70.

Birkeland SA Storm HH . Risk for Tumor and Other Disease Transmission by Transplantation: A Population-Based Study of Unrecognized Malignancies and Other Diseases in Organ Donors. Transplantation (2002) 74(10):1409–13. 10.1097/00007890-200211270-00012

71.

Chen KT Olszanski A Farma JM . Donor Transmission of Melanoma Following Renal Transplant. Case Rep Transplant (2012) 2012:764019. 10.1155/2012/764019

72.

Cankovic M Linden MD Zarbo RJ . Use of Microsatellite Analysis in Detection of Tumor Lineage as a Cause of Death in a Liver Transplant Patient. Arch Pathol Lab Med (2006) 130(4):529–32. 10.1043/1543-2165(2006)130[529:UOMAID]2.0.CO;2

73.

Morris-Stiff G Steel A Savage P Devlin J Griffiths D Portman B et al Transmission of Donor Melanoma to Multiple Organ Transplant Recipients. Am J Transplant (2004) 4(3):444–6. 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2004.00335.x

74.

Izraely S Sagi-Assif O Klein A Meshel T Tsarfaty G Pasmanik-Chor M et al The Metastatic Microenvironment: Brain-Residing Melanoma Metastasis and Dormant Micrometastasis. Int J Cancer (2012) 131(5):1071–82. 10.1002/ijc.27324

75.

Cabrera R Recule F . Unusual Clinical Presentations of Malignant Melanoma: A Review of Clinical and Histologic Features With Special Emphasis on Dermatoscopic Findings. Am J Clin Dermatol (2018) 19:15–23. 10.1007/s40257-018-0373-6

76.

González-Cruz C Ferrándiz-Pulido C García-Patos BV . Melanoma in Solid Organ Transplant Recipients. Actas Dermo-Sifiliograficas (2021) 112:216–24. 10.1016/j.ad.2020.11.005

77.

Dicker TJ Kavanagh GM Herd RM Ahmad T McLaren KM Chetty U et al A Rational Approach to Melanoma Follow-Up in Patients With Primary Cutaneous Melanoma. Scottish Melanoma Group. Br J Dermatol (1999) 140(2):249–54. 10.1046/j.1365-2133.1999.02657.x

78.

Toren KL Parlette EC . Managing Melanoma In Situ. Semin Cutan Med Surg (2010) 29(4):258–63. 10.1016/j.sder.2010.10.002

79.

Wright FC Souter LH Kellett S Easson A Murray C Toye J et al Primary Excision Margins, Sentinel Lymph Node Biopsy, and Completion Lymph Node Dissection in Cutaneous Melanoma: A Clinical Practice Guideline. Curr Oncol (2019) 26(4):e541–e550. 10.3747/co.26.4885

80.

Hollestein LM Nijsten T . Survival Is Excellent For Most Patients With Thin Melanoma, But Patients May Die From Thin Melanoma. Br J Dermatol (2021) 184:4. 10.1111/bjd.19208

81.

Lo SN Scolyer RA Thompson JF . Long-Term Survival of Patients With Thin (T1) Cutaneous Melanomas: A Breslow Thickness Cut Point of 0.8 Mm Separates Higher-Risk and Lower-Risk Tumors. Ann Surg Oncol (2018) 25(4):894–902. 10.1245/s10434-017-6325-1

82.

Isaksson K Mikiver R Eriksson H Lapins J Nielsen K Ingvar C et al Survival in 31 670 Patients With Thin Melanomas: A Swedish Population-Based Study. Br J Dermatol (2021) 184(1):60–7. 10.1111/bjd.19015

83.

Crowley NJ Seigler HF . Late Recurrence of Malignant Melanoma: Analysis of 168 Patients. Ann Surg (1990) 212(2):173–7. 10.1097/00000658-199008000-00010

84.

Piérard-Franchimont C Hermanns-Lê T Delvenne P Piérard GE . Dormancy of Growth-Stunted Malignant Melanoma: Sustainable and Smoldering Patterns. Oncol Rev (2014) 8:252. 10.4081/oncol.2014.252

85.

Tseng WW Fadaki N Leong SP . Metastatic Tumor Dormancy in Cutaneous Melanoma: Does Surgery Induce Escape?. Cancers (2011) 3:730–46. 10.3390/cancers3010730

86.

Linde N Fluegen G Aguirre-Ghiso JA . The Relationship between Dormant Cancer Cells and Their Microenvironment. Adv Cancer Res (2016) 132:45–71. 10.1016/bs.acr.2016.07.002

87.

Benoni H Eloranta S Ekbom A Wilczek H Smedby KE . Survival Among Solid Organ Transplant Recipients Diagnosed With Cancer Compared to Nontransplanted Cancer Patients—A Nationwide Study. Int J Cancer (2020) 146(3):682–91. 10.1002/ijc.32299

88.

Robbins HA Clarke CA Arron ST Tatalovich Z Kahn AR Hernandez BY et al Melanoma Risk and Survival Among Organ Transplant Recipients. J Invest Dermatol (2015) 135(11):2657–65. 10.1038/jid.2015.312

89.

Kaliki S Shields CL . Uveal Melanoma: Relatively Rare but Deadly Cancer. Eye (Basingstoke) (2017) 31:241–57. 10.1038/eye.2016.275

90.

Carvajal RD Schwartz GK Tezel T Marr B Francis JH Nathan PD . Metastatic Disease From Uveal Melanoma: Treatment Options and Future Prospects. Br J Ophthalmol (2017) 101:38–44. 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2016-309034

91.

Altieri L Eguchi M Peng DH Cockburn M . Predictors of Mucosal Melanoma Survival in a Population-Based Setting. J Am Acad Dermatol (2019) 81(1):136–42. 10.1016/j.jaad.2018.09.054

92.

Dholakia S Johns R Muirhead L Papalois V Crane J . Renal Donors With Prostate Cancer, No Longer a Reason to Decline. Transplant Rev (2016) 30:48–50. 10.1016/j.trre.2015.06.001

93.

Prostate Cancer — Cancer Stat Facts (2023). Available from: https://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/prost.html (Accessed: October 11, 2023).

94.

Yin M Bastacky S Chandran U Becich MJ Dhir R . Prevalence of Incidental Prostate Cancer in the General Population: A Study of Healthy Organ Donors. J Urol (2008) 179(3):892–5. 10.1016/j.juro.2007.10.057

95.

Rosales BM De La Mata N Vajdic CM Kelly PJ Wyburn K Webster AC . Cancer Mortality in Kidney Transplant Recipients: An Australian and New Zealand Population-Based Cohort Study, 1980–2013. Int J Cancer (2020) 146(10):2703–11. 10.1002/ijc.32585

96.

Na R Grulich AE Meagher NS McCaughan GW Keogh AM Vajdic CM . Comparison of De Novo Cancer Incidence in Australian Liver, Heart and Lung Transplant Recipients. Am J Transplant (2013) 13(1):174–83. 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2012.04302.x

97.

Short E Warren AY Varma M . Gleason Grading of Prostate Cancer: A Pragmatic Approach. Diagn Histopathology (2019) 25:371–8. 10.1016/j.mpdhp.2019.07.001

98.

Gleason DF . Histologic Grading of Prostate Cancer: A Perspective. Hum Pathol (1992) 23(3):273–9. 10.1016/0046-8177(92)90108-f

99.

Ross HM Kryvenko ON Cowan JE Simko JP Wheeler TM Epstein JI . Do Adenocarcinomas of the Prostate With Gleason Score (GS)≤6 Have the Potential to Metastasize to Lymph Nodes?Am J Surg Pathol (2012) 36:1346–52. 10.1097/PAS.0b013e3182556dcd

100.

Skalski M Gierej B Nazarewski Ł Ziarkiewicz-Wróblewska B Zieniewicz K . Prostate Cancer in Deceased Organ Donors: Loss of Organ or Transplantation with Active Surveillance. Transpl Proc (2018) 50(7):1982–4. 10.1016/j.transproceed.2018.02.129

101.

Doerfler A Tillou X Le Gal S Desmonts A Orczyk C Bensadoun H . Prostate Cancer in Deceased Organ Donors: A Review. Transplant Rev (2014) 28:1–5. 10.1016/j.trre.2013.10.003

102.

Loh E Couch FJ Hendricksen C Farid L Kelly PF Acker MA et al Development of Donor-Derived Prostate Cancer in a Recipient Following Orthotopic Heart Transplantation. JAMA (1997) 277(2):133–7. 10.1001/jama.1997.03540260047034

103.

Desai R Collett D Watson CJE Johnson P Evans T Neuberger J . Estimated Risk of Cancer Transmission from Organ Donor to Graft Recipient in a National Transplantation Registry. Br J Surg (2014) 101(7):768–74. 10.1002/bjs.9460

104.

Forbes GB Goggin MJ Dische FE Saeed IT Parsons V Harding MJ et al Accidental Transplantation of Bronchial Carcinoma From a Cadaver Donor to Two Recipients of Renal Allografts. J Clin Pathol (1981) 34(2):109–15. 10.1136/jcp.34.2.109

105.

Göbel H Gloy J Neumann J Wiech T Pisarski P Böhm J . Donor-Derived Small Cell Lung Carcinoma in a Transplanted Kidney. Transplantation (2007) 84:800–2. 10.1097/01.tp.0000281402.55745.e6

106.

Mazzone PJ Lam L . Evaluating the Patient With a Pulmonary Nodule: A Review. JAMA (2022) 327:264–73. 10.1001/jama.2021.24287

107.

Sonbol MB Halling KC Douglas DD Ross HJ . A Case of Donor-Transmitted Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer After Liver Transplantation: An Unwelcome Guest. Oncologist (2019) 24(6):e391–3. 10.1634/theoncologist.2018-0517

108.

Lipshutz GS Baxter-Lowe LA Nguyen T Jones KD Ascher NL Feng S . Death From Donor-Transmitted Malignancy Despite Emergency Liver Retransplantation. Liver Transplant (2003) 9(10):1102–7. 10.1053/jlts.2003.50174

109.

Penn I . Evaluation of the Candidate With a Previous Malignancy. Liver Transpl Surg. (1996) 2(5 Suppl 1):109–13.

110.

Benkö T Hoyer DP Saner FH Treckmann JW Paul A Radunz S . Liver Transplantation from Donors With a History of Malignancy: A Single-Center Experience. Transpl Direct (2017) 3(11):e224. 10.1097/TXD.0000000000000738

111.

Riihimaki M Hemminki A Sundquist J Hemminki K . Patterns of Metastasis in Colon and Rectal Cancer. Sci Rep (2016) 6:29765. 10.1038/srep29765

112.

Feng S Buell JF Chari RS DiMaio JM Hanto DW . Tumors and Transplantation: The 2003 Third Annual ASTS State-Of-The-Art Winter Symposium. Am J Transplant (2003) 3:1481–7. 10.1046/j.1600-6143.2003.00245.x

113.

Eccher A Girolami I Marletta S Brunelli M Carraro A Montin U et al Donor-Transmitted Cancers in Transplanted Livers: Analysis of Clinical Outcomes. Liver Transplant (2021) 27(1):55–66. 10.1002/lt.25858

114.

Manzi J Hoff CO Ferreira R Pimentel A Datta J Livingstone AS et al Targeted Therapies in Colorectal Cancer: Recent Advances in Biomarkers, Landmark Trials, and Future Perspectives. Cancers (2023) 15:3023. 10.3390/cancers15113023

115.

Hernandez-Alejandro R Ruffolo LI Sasaki K Tomiyama K Orloff MS Pineda-Solis K et al Recipient and Donor Outcomes After Living-Donor Liver Transplant for Unresectable Colorectal Liver Metastases. JAMA Surg (2022) 157(6):524–30. 10.1001/jamasurg.2022.0300

116.

Dueland S Smedman TM Syversveen T Grut H Hagness M Line PD . Long-Term Survival, Prognostic Factors, and Selection of Patients with Colorectal Cancer for Liver Transplant: A Nonrandomized Controlled Trial. JAMA Surg (2023) 158:e232932. 10.1001/jamasurg.2023.2932

117.

Manzi J Hoff CO Ferreira R Glehn-Ponsirenas R Selvaggi G Tekin A et al Cell-Free DNA as a Surveillance Tool for Hepatocellular Carcinoma Patients After Liver Transplant. Cancers (Basel) (2023) 15(12):3165. 10.3390/cancers15123165

118.

Types of Thyroid Cancer. American Cancer Society (2023). Available from: https://www.cancer.org/cancer/types/thyroid-cancer/about/what-is-thyroid-cancer.html (Accessed: October 11, 2023).

119.

Verburg FA Mäder U Tanase K Thies ED Diessl S Buck AK et al Life Expectancy Is Reduced in Differentiated Thyroid Cancer Patients ≥ 45 Years Old With Extensive Local Tumor Invasion, Lateral Lymph Node, or Distant Metastases at Diagnosis and Normal in All Other DTC Patients. J Clin Endocrinol Metab (2013) 98(1):172–80. 10.1210/jc.2012-2458

120.

Perros P Colley S Boelaert K Evans C Evans R Gerrard G et al Guidelines for the Management of Thyroid Cancer. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) (2014) 81:1–122. 10.1111/cen.12515

121.

Cooper DS Doherty GM Haugen BR Kloos RT Lee SL Mandel SJ et al Consensus Statement on the Terminology and Classification of Central Neck Dissection for Thyroid Cancer. Thyroid (2009) 19:1153–8. 10.1089/thy.2009.0159

122.

Van Leeuwen MT Webster AC McCredie MRE Stewart JH McDonald SP Amin J et al Effect of Reduced Immunosuppression After Kidney Transplant Failure on Risk of Cancer: Population Based Retrospective Cohort Study. BMJ (Online) (2010) 340(7744):c570. 10.1136/bmj.c570

123.

Greenhall GHB Ibrahim M Dutta U Doree C Brunskill SJ Johnson RJ et al Donor-Transmitted Cancer in Orthotopic Solid Organ Transplant Recipients: A Systematic Review. Transpl Int (2022) 35:10092. 10.3389/ti.2021.10092

124.

Malvi D Vasuri F Albertini E Carbone M Novelli L Mescoli C et al Donors Risk Assessment in Transplantation: From the Guidelines to Their Real-World Application. Pathol Res Pract (2024) 255:155210. 10.1016/j.prp.2024.155210

125.

Lim WH Au E Teixeira-Pinto A Ooi E Opdam H Chapman J et al Donors With a Prior History of Cancer: Factors of Non-Utilization of Kidneys for Transplantation. Transpl Int (2023) 36:11883. 10.3389/ti.2023.11883

126.

Greenhall GHB Rous BA Robb ML Brown C Hardman G Hilton RM et al Organ Transplants From Deceased Donors With Primary Brain Tumors and Risk of Cancer Transmission. JAMA Surg (2023) 158(5):504–13. 10.1001/jamasurg.2022.8419

Summary

Keywords

risk, cancer, donor, malignancy, transplant surgery

Citation

Turra V, Manzi J, Rombach S, Zaragoza S, Ferreira R, Guerra G, Conzen K, Nydam T, Livingstone A, Vianna R and Abreu P (2025) Donors With Previous Malignancy: When Is It Safe to Proceed With Organ Transplantation?. Transpl Int 38:13716. doi: 10.3389/ti.2025.13716

Received

29 August 2024

Accepted

07 January 2025

Published

24 January 2025

Volume

38 - 2025

Updates

Copyright

© 2025 Turra, Manzi, Rombach, Zaragoza, Ferreira, Guerra, Conzen, Nydam, Livingstone, Vianna and Abreu.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Phillipe Abreu, phillipe.abreu@cuanschutz.edu

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.