- 1Department of Surgical Sciences, University of Turin, Turin, Italy

- 2Cardiovascular and Thoracic Department, Azienda Ospedaliero Universitaria Città della Salute e della Scienza di Torino, Turin, Italy

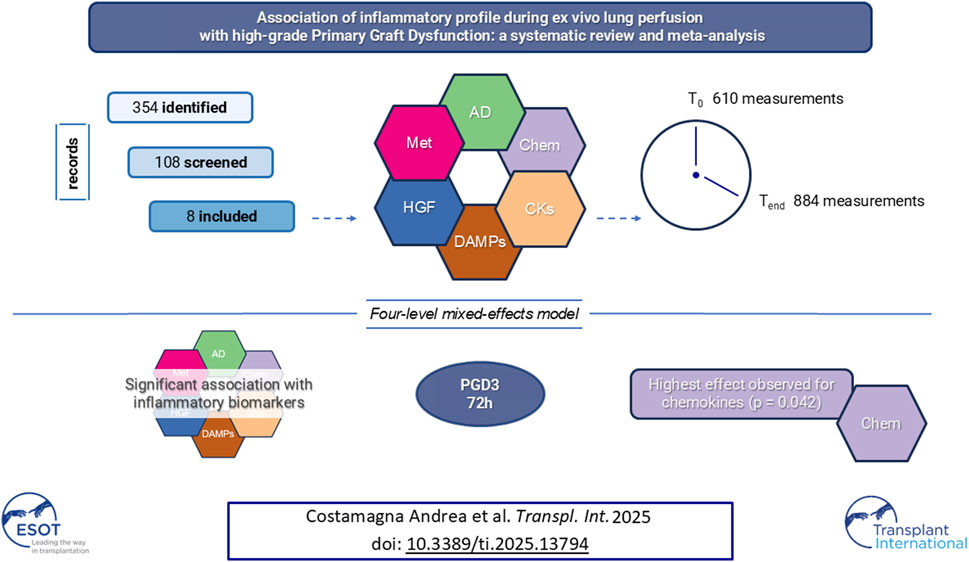

PGD3 is the manifestation of ischemia-reperfusion injury which results from inflammation and cell death and is associated with poor outcome. This systematic-review and meta-analysis of non-randomized controlled trials on patients undergoing Ltx with reconditioned lungs via EVLP, aims to assess the association between the levels of proinflammatory biomarkers during EVLP and PGD3 development within the firsts 72 h post-Ltx. Biomarkers were categorized by timing (1-hour, T0 and 4-hours, Tend from EVLPstart) and by their biological function (adhesion molecules, chemokines, cytokines, damage-associated-molecular-patterns, growth-factors, metabolites). We employed a four-level mixed-effects model with categorical predictors for biomarker groups to identify differences between patients with PGD3 and others. The single study and individual measurements were considered random intercepts. We included 8 studies (610 measurements at T0 and 884 at Tend). The pooled effect was 0.74 (p = 0.021) at T0, and 0.90 (p = 0.0015) at Tend. The four-level model indicated a large pooled correlation between developing PGD3 at 72 h post-Ltx and inflammatory biomarkers values, r = 0.62 (p = 0.009). Chemokine group showed the strongest association with the outcome (z-value = 1.26, p = 0.042). Pooled panels of inflammation markers, particularly chemokines, measured at T0 or at Tend, are associated with the development of PGD3 within the first 72 h after Ltx.

Systematic Review Registration: https://osf.io/gkxzh/.

Introduction

Ex vivo lung perfusion (EVLP) is a well-established platform to assess and potentially treat suboptimal donor lungs to mitigate organ shortage expanding the pool of lungs suitable for transplantation [1]. During 6 h of ventilation and perfusion, conventional clinical parameters such as respiratory mechanics, gas exchange, hemodynamics and radiologic appearance are monitored to assess organ suitability for transplantation. Additional measures and techniques have been proposed to enhance the accuracy of lung evaluation during EVLP, such as the application of machine learning models to radiographic findings [2], direct lung ultrasound assessment [3, 4] and tissue microdialysis for assessing lung tissue metabolism [5].

However, EVLP lungs may develop primary graft dysfunction (PGD), which is an early form of acute lung injury that occurs during the firsts 72 postoperative hours [6]. Severe form of PGD (namely, grade 3 PGD), characterized by PaO2/FiO2 < 200 mmHg, represents an established risk factor for poor recipients survival [7–9] and bronchiolitis obliterans development [6, 8].

PGD is the clinical manifestation of ischemia-reperfusion induced lung injury (IRI), which results from the complex interplay between inflammation, cell death and leukocyte activation in the donor lung [6, 10]. After lung procurement, damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs), such as HMGB1 and nuclear and mitochondrial DNA, are released as a consequence of cell death occurring during cold ischemic time and subsequent rewarming and reperfusion [11–15]. These endogenous molecules stimulate in turn a variety of immune (e.g., macrophages and lymphocytes) and non-immune cells (e.g., lung epithelial and endothelial cells and fibroblasts) to release pro-inflammatory mediators, such as chemokines and cytokines [10, 16]. Both pro-inflammatory mediators and DAMPS promote the expression of adhesion molecules, associated with endothelial activation and consequent leucocyte recruitment, leading to endothelial permeability increase with oedema formation [11, 17–19]. In addition, recent studies show that point of care protein assay based on IL6 and 8 cytokine levels in lung perfusate has a good accuracy in predicting recipients outcome [20]. To identify lung recipients who at higher risk of PGD 3 development after EVLP and to optimize their treatment, an appreciation for the effects of different classes of biomarkers measured in lung perfusate is relevant. The aim of this systematic review and meta-analysis is to evaluate the association between the levels of pro-inflammatory biomarkers collected at the start or at the end of the EVLP procedure and the development of PGD 3 in the Ltx recipient within the firsts 72 post-operative hours. We hypothesized that different classes of soluble mediators in lung perfusate would exert different effects on PGD3 development in lung transplant recipients.

Materials and Methods

This systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and non-randomized controlled trials (NRCTs) was prepared in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement [21]. The Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Intervention was chosen as the methodological guidance [22]. The protocol was registered in PROSPERO (PROSPERO #CRD42022296486).

The following databases were used: PubMed, Embase, and Scopus. Searches were conducted for studies published up to 03 August 2023. RCTs and NRCTs published in English, and Italian were considered eligible for inclusion. Other potentially relevant studies were searched in study registers (i.e., PROSPERO, ClinicalTrials.gov), and in gray literature sources. Specific search strategies were created for each database (Supplementary Figure S1).

Each step outlined by the PRISMA flow diagram, along with corresponding lists of included and excluded articles together with their respective justifications, can be found online.1

Eligibility Criteria

The search was restricted exclusively to RCTs and NRCTs, encompassing participants who satisfied the subsequent inclusion criteria: adult human patients of all genders undergoing Ltx employing reconditioned lungs via EVLP.

The exclusion criteria were: investigations encompassing organ system care (OCS), and studies that reported inflammatory biomarkers at a timepoint preceding EVLP.

Patients who developed PGD with a P/F ratio < 200 mmHg along with radiographic lung infiltrates or requiring extracorporeal life support, are classified as having PGD 3 [23]. Considering the different impact on survival outcomes, we categorized our study population into those with severe PGD (PGD 3) and those with grade 1 or 2 PGD, or no PGD. The primary outcomes were biomarker levels measured in the perfusate at 1 h (T0) and 4 h (Tend) from the start of EVLP. We selected all studies in which specific mediators of inflammation -e.g., Interleukin-8, Interleukin-6, etc.- were quantified in their genotypic or phenotypic expression related to the development of PGD 3 at 72 h.

Selection Process

Search results were collated and exported to EndNote V.X9 (Clarivate Analytics, PA, United States). Duplicates were automatically removed. The review process consisted of two screening levels using Rayyan QCRI online software [24]:

(1) a title and abstract review

(2) full-text review

For both levels, 2 authors (AC and EB) independently screened the articles, with conflicts resolved by a third author (VF).

Data were extracted in a planned standardized Excel spreadsheet (study characteristics, year of the study, type of population, biomarkers detected, timing of measures, and main results). When the data were not directly available, we used WebPlotDigitizer or directly contacted the authors.

To prevent biased inclusion of data based on the results, the authors decided that 1) where trialists reported both final values and changes from baseline values for the same outcome, final values were recorded; 2) where trialists reported both unadjusted and adjusted values for the same outcome, unadjusted values were extracted; 3) where trialists reported data analyzed based on the intention-to-treat sample and another sample (e.g., per-protocol, as-treated), data from the former were extracted.

Subgroup Analysis

Biomarkers were divided into subgroups basing on their biological function and mechanism of action in specific inflammatory pathway. Six categories were identified: adhesion molecules (sE-selectin, sICAM, vCAM, ET-1, Big ET-1), chemokines (IL-8, MCP, GROα, MIP-1a, MIP-1b), cytokines (IL1β, IL6, TNFα), damage-associated molecular patterns (M30, HMGB, nuDNA, mtDNA), growth factors (M-CSF, G-CSF) endogenous metabolites produced during inflammatory phenomena (CO and NOx).

Study Risk of Bias Assessment

Two authors (AC and EB) independently assessed the risk of bias through the Risk Of Bias In NRCTs – of Interventions (ROBINS-i) tool [25]. RoB graph was created through RobVis visualization tool [26]. For NRCTs, an initial assessment considered potential confounders and co-interventions. Subsequently, the risk of bias was evaluated as either “low,” “uncertain,” or “high” in various domains, including confounders, participant selection, intervention classification, deviation from intended intervention, missing data, outcome measurement, and reported results. Any disagreements were resolved by a third reviewer (VF).

Statistical Analysis

Since we assessed a continuous outcome (pro-inflammatory status) measured through different variables, we computed the standardized mean difference (SMD) along with its associated 95% confidence interval (95% CI). In the process of pooling the data, we employed a random-effects model and inverse variance method. To ensure robust performance in this analysis, we opted for the restricted maximum likelihood estimator (REML) for tau2. We used Q-Profile method for CI of tau2 and tau. We used the Hartung-Knapp adjustment for random effects model. The prediction interval was based on t-distribution. The calculation of SMD was carried out utilizing Hedges’ g method. The outcomes were represented using either forest plots or drapery plots, as suggested in the literature [27]. Prediction intervals were calculated and represented in the respective forest plots [28]. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05. To evaluate the size of the effect of the SMD, we considered levels of 0.2, 0.5, 0.8 as small, medium, and large effects. Statistical heterogeneity was determined with the Q statistic and I2, with values of 25%, 50%, and 75% taken to indicate low, moderate, and high levels of heterogeneity, respectively [22]. To identify potential publication bias, the Egger’s regression test was performed.

Since study participants are nested within studies, we set a four-level meta-analysis to assess potential moderators of the overall effect using a four-level mixed-effects model. We included random effects for specific factors that could influence model reliability, such as the research group (level 4), individual authors (level 3 – nested within level 4), and the marker of interest (level 2 – nested within level 3). Level 1 represented individual measurements. As fixed effects, we incorporated the specific group of molecules (e.g., chemokines, cytokines, etc.), categorized based on their potential molecular mechanisms contributing to PGD, and Timing, which referred to the timing of individual measurements. Timing was defined as either immediately after the lung transplant subjected to EVLP or days later, categorized as T0 vs. Tend. We used the REML method to estimate model parameters. To evaluate the model’s fit, we reported the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC). After establishing the suitability of the four-level model, we proceeded to assess potential moderators of the overall effect. The effect of individual biomarker categories was determined by adding the intercept value to their estimate [27].

We performed a sensitivity analysis using the same four-level meta-analysis, but restricted it to specific timepoints, namely, T0 and Tend.

All the analysis were performed with R studio using the packages dmetar, meta, metafor version 2023.06.0+421 (2023.06.0+421) [29].

Results

The search strategy retrieved 350 articles from databases and 4 from registers. After removing the duplicates, the remaining 108 articles were independently screened for titles and abstracts by 2 authors (AC and EB), and 96 records were excluded. A detailed list for each exclusion reason is available at link.1 Full texts of the remaining 12 records were screened, and 5 records were excluded. One last paper was added after a careful revision of the bibliography [30].

A total of eight NRCTs were included [12, 19, 20, 30–34] in the systematic review and meta-analysis. A detailed selection process is shown in the PRISMA flowchart (Supplementary Figure S1) and in a repository online.1 Then two authors (AC and EB) independently extracted the data following study protocol.

Risk of Bias in Studies

All the studies included were judged of low RoB arising from the randomization process with ROBINS-I tool for NRCTs (Figure 1). The overall risk of bias was moderate-low due to the well-selected population, uniform protocols for detecting inflammatory mediators, and a low number of missing data. Potential confounders, such as the cutoff values for the measured variables and the kits used to detect the biomarkers, were identified.

Figure 1. Risk of bias assessment using the Risk Of Bias In Non-randomised Studies - of Interventions (ROBINS-I) tool for the selected studies included in the meta-analysis.

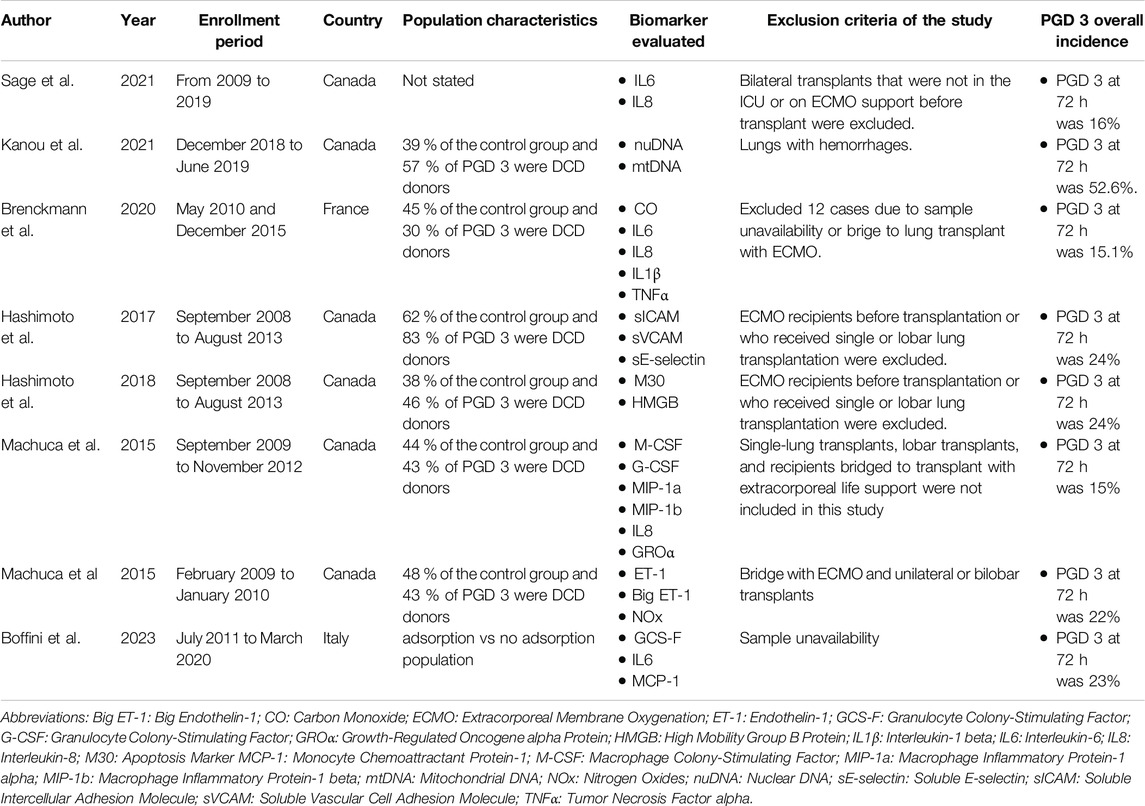

Description of Included Studies

A detailed description of the included studies is reported in Table 1.

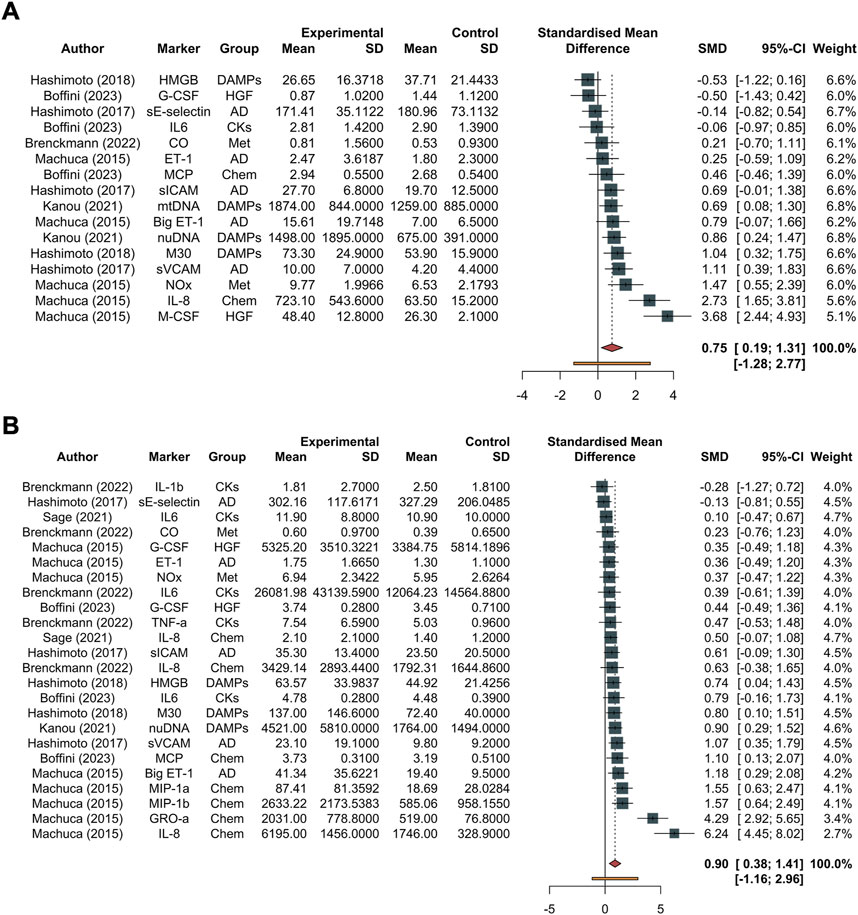

Biomarkers at Initial T0

In total, 610 measurements were conducted at the initial time. The inflammation mediators considered were sE-selectin, sICAM, vCAM, ET-1, Big ET-1, IL8, MCP, GROα, MIP1a, MIP1b, IL1β, IL6, TNFα, M30, HMGB, nuDNA, mtDNA, M-CSF, GCS-F, inhaled CO and NOx (Figure 2, and Supplementary Figure S2). The pooled effect according to the random-effects model was 0.75, with the 95% CI ranging from 0.19 to 1.31 (Figure 2 and Supplementary Figure S2). The effect size was 2.84 (p = 0.012), detecting a significantly higher probability to develop PGD grade 3 at 72 h post-transplant as the inflammatory biomarkers increase. The restricted maximum likelihood method estimated a between-study heterogeneity variance of τ2, which was 0.82 with a 95% CI of (0.38–2.66) (Supplementary Table S1). The statistical heterogeneity (I2) was 78.6%, with a 95% CI of (66%–87%) and the significance test of Q (Q = 70, df = 15, p < 0.001) confirmed this heterogeneity (Figure 2). In the Eggers’ test, the intercept of our regression model was 4.66 (95% CI −0.67–9.98). This is non-significant (t = 1.714, p-value = 0.11), and indicates that the data in the funnel plot are quite symmetrical (Supplementary Figure S2).

Figure 2. Forest plot of studies assessing inflammatory biomarkers. These are detailed in the column labeled “Marker,” accompanied by their corresponding groups denoted as “Group.” The experimental group corresponds to the PGD grade 3 at 72 h group, while the control group represents the non-PGD grade 3 group. The standardized mean difference (SMD), along with its respective 95% confidence interval (95% CI) and the individual weight for each study, is reported on the right. In the forest plot, squares placed to the right—considering 0 as the midpoint—indicate higher marker levels in the experimental group. (A) Forest plot for overall studies, excluding outliers, (B) all the studies. Abbreviations: AD, adhesion molecules; CKs, chemokines; DAMPs, damage-associated molecular patterns; Hematop GF, growth factors; sE-selectin, endothelial selectin; sICAM, intercellular adhesion molecule; vCAM, vascular cell adhesion molecule; ET-1, endothelin-1; Big ET-1, big endothelin-1; IL-8, interleukin-8; MCP, monocyte chemoattractant protein; GROα, growth-related oncogene alpha; MIP-1α, macrophage inflammatory protein-1 alpha; MIP-1β, macrophage inflammatory protein-1 beta; IL-1β, interleukin-1 beta; IL-6, interleukin-6; TNF-α, tumor necrosis factor alpha; M30, M30; HMGB, high mobility group box 1; nuDNA, nuclear DNA; mtDNA, mitochondrial DNA; M-CSF, macrophage colony-stimulating factor; G-CSF, granulocyte colony-stimulating factor.

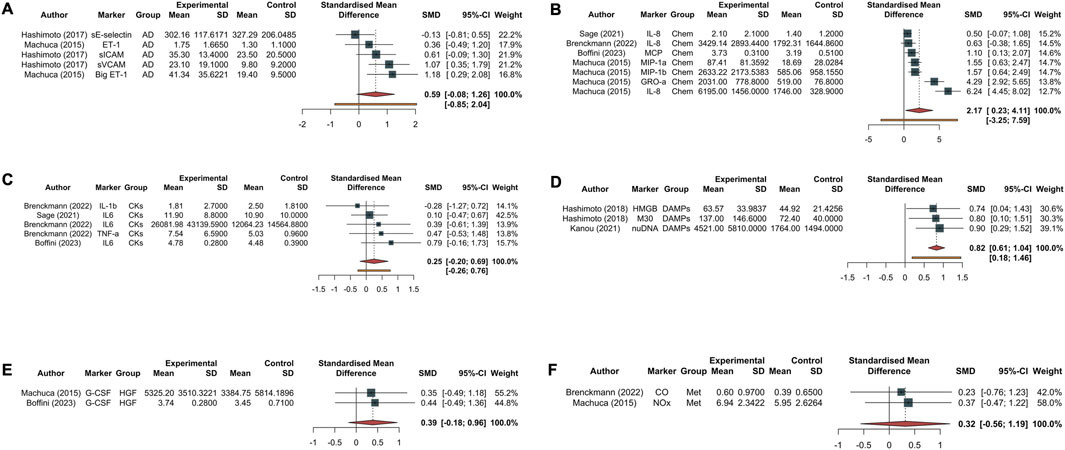

Biomarkers at Tend

In total, 884 distinct measurements were conducted at the final time. The inflammation mediators considered were sE-selectin, sICAM, vCAM, ET-1, Big ET-1, IL8, MCP, GROα, MIP1a, MIP1b, IL1β, IL6, TNFα, M30, HMGB, nuDNA, mtDNA, M-CSF, GCS-F, inhaled CO and NOx. The pooled effect according to the random-effects model was 0.90, with the 95% CI ranging from 0.38 to 1.41 (Figure 2, and Supplementary Figure S3). The effect size was 3.60 (p = 0.0015), detecting a significantly higher probability to develop PGD 3 at 72 h post-Ltx as the inflammatory biomarkers increase. The REML method estimated a between-study heterogeneity variance of τ2, which was 0.93 with a 95% CI of (0.61–3.32) (Supplementary Table S1). The I2 was 74.9%, with a 95% CI of (62.7%–83.1%), and the significance test of Q (Q = 92, df = 23, p < 0.001) confirmed this heterogeneity.

In the Eggers’ test, the intercept of our regression model was 4.94 (95% CI 2.10–7.77). This is significant (t = 3.42, p-value = 0.025), and indicates that the data in the funnel plot are asymmetrical (Supplementary Figure S3). Single molecules are reported divided based on their category and the timing in Figure 3 (biomarkers at Tend) and Supplementary Figure S4 (biomarkers at T0).

Figure 3. Forest plot of studies assessing inflammatory biomarkers at Tend corresponding to 4 h from EVLP start. Each plot represents a specific group of biomarkers: adhesion molecules [AD, (A)], chemokines [Chem, (B)], cytokines [CKs, (C)], damage-associated molecular patterns [DAMPs, (D)], growth factors [HGF, (E)], and endogenous metabolites produced during inflammatory phenomena such as carbon monoxide and nitric oxide metabolite [Met, (F)]. The experimental group corresponds to the PGD grade 3 at 72 h, while the control group represents the non-PGD grade 3. The standardized mean difference (SMD), accompanied by its respective 95% confidence interval (95% CI) and the individual weight for each study, is reported on the right. In the forest plot, the placement of squares to the right of the plot—taking 0 as the midpoint—indicates higher marker levels in the experimental group. Abbreviations: sE-selectin, endothelial selectin; sICAM, intercellular adhesion molecule; vCAM, vascular cell adhesion molecule; ET-1, endothelin-1; Big ET-1, big endothelin-1; IL-8, interleukin-8; MCP, monocyte chemoattractant protein; GROα, growth-related oncogene alpha; MIP-1α, macrophage inflammatory protein-1 alpha; MIP-1β, macrophage inflammatory protein-1 beta; IL-1β, interleukin-1 beta; IL-6, interleukin-6; TNF-α, tumor necrosis factor alpha; M30, M30; HMGB, high mobility group box 1; nuDNA, nuclear DNA; mtDNA, mitochondrial DNA; M-CSF, macrophage colony-stimulating factor; G-CSF, granulocyte colony-stimulating factor; CO, carbon monoxide; NOx, nitric oxide metabolite.

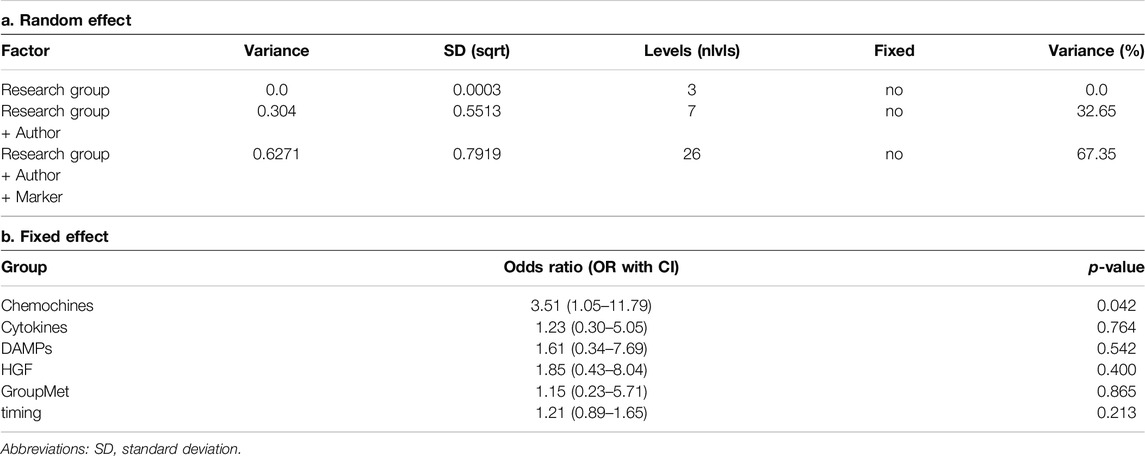

Four-Level Mixed Linear Analysis for Biomarkers Subgroups

We found a large pooled correlation based on the four-level meta-analytic model (r = 0.62–95% CI: 1.21–3.50; p = 0.009 - Table 2), meaning that there seems to be a substantial association between developing PGD 3 at 72 h post-Ltx and inflammatory biomarkers.

The estimated variance components were τ2Level2 = 0.63, τ2Level3 = 0.30 and τ2Level4 = 0.00. This means that I2Level2 = 67% of the total variation can be attributed to within-markers heterogeneity, and I2Level3 = 33% to within-authors heterogeneity, while the within-research group heterogeneity was approximately I2Level4 = 0%. Overall, this indicates that there is substantial between-study heterogeneity on the second level, or differences within studies. Yet, we also see that a large proportion of the total variance, more than one-fifth, can be explained by differences within markers (Level 3). In this model, the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) of the four-level model was 109.7, indicating that the model fits the data well.

We checked if correlations differed depending on the biomarker group (AD, CKs, Chemokines, DAMPs, Hematop GF, Met) using a four-level moderator model (p = 0.235). In the model, the only group that showed a significant difference was the Chemokine group, with a z-value of 1.26 (p = 0.042). From our model, the timepoints were not associated with the outcome (OR 1.21 95% CI [0.89–1.65], p-value 0.213). We conducted a sensitivity analysis using data only at the timepoint T0 or at the timepoint Tend, but the findings were consistent with the previous model (Supplementary Table S1).

Discussion

In this systematic review and meta-analysis, soluble pro-inflammatory markers measured during EVLP were associated to PGD grade 3 at 72 h after transplantation. Chemokines levels exerted the highest effect on PGD development. Moreover, the timing at which these markers were collected did not affect their predictive value. In fact, patients with grade 3 PGD had higher biomarker levels measured at both early and late stages of EVLP.

The relationship between inflammatory molecules during IRI and the development of PGD is the consequence of the warm and cold ischemia following donor organ retrieval. Pro-inflammatory mediators can be activated during CIT as a result of oxidative stress, sodium Na+/K+ ATPase inactivation, calcium overload, and a variety of cell death mechanisms, including apoptosis, necrosis, autophagy, pyroptosis and ferroptosis [10, 35, 36].

Cellular stress triggers the release of DAMPs, mediating acute lung injury through TLR bonding. HMGB1 and nucleic acids were higher at Tend in the high-grade PGD patients [12, 33]; while the circulating amount of DNA was also higher at T0 in the PGD3 cohort, reflecting the amount of cell injury and death following CIT, HMGB1 levels were instead lower. In fact, HMGB1 can be actively released by alveolar macrophages, lymphocytes and epithelial cells too, after reperfusion, and maybe sustaining a pro-inflammatory effect in the damaged grafts [11–15]. High CKs levels (namely, IL1β, TNFα and IL6) at Tend might reflect lung injury, but in the examined studies the association between the total amount of these molecules and the development of PGD3 was not unanimous [20, 31, 32]. Hoffman et al. found no differences in terms of TNFα and IL1β in the plasma of LTx recipients with or without PGD3, and a significant increase in terms of IL-6 levels in patients with high grade PGD only 48–72 h after surgery [37]. This fact might corroborate the hypothesis that these CKs do not reflect the amount of tissue damage right after CIT. The included studies instead showed a strong association between chemokines levels in perfusate and PGD3, in particular when measured at the end of the procedure [20, 31, 32, 34]. Chemokines are involved in the recruitment of neutrophils (IL-8) and monocytes (MCP). IL-8 levels in particular are associated with worse graft function [10, 20, 37] and were also found to be higher at T0 in the recipients with worse outcome after transplantation [34]. Although G-CSF and M-CSF might theoretically play a role as the signature for a higher pro-inflammatory milieu, considered globally they were not strongly associated with PGD3 development, except for M-CSF levels in perfusate at T0 [31, 34] In fact, M-CSF is involved in monocytes and macrophages proliferation and differentiation [38], plays a role in the pathogenesis of pulmonary fibrosis [38] and has been associated with hyperinflammatory state in COVID-19 patients [39] Soluble adhesion molecules are released into circulation from the cell surface and their levels correlate with the degree of endothelial activation during inflammation [18, 19]. They are known to be upregulated in lung tissue samples from ARDS patients who died for Gram-negative bacteria induced septic shock [40] and in ARDS patients with worse outcome [17, 41, 42].Adhesion molecules were increased in every graft, except from sVCAM-1, which remained stable during the procedure only in those lungs which did not develop PGD3 [19]. Our metanalysis confirms that sVCAM-1 levels are constantly higher in the PGD3 recipients both at the beginning and at the end of EVLP. Moreover, the higher level of Big ET-1 in PGD3 grafts might rather reflect an alteration in capillary permeability and recruitment of inflammatory cells [30].

Compared to lungs that are transplanted without examination, EVLP provides a unique platform for dynamically assessing the inflammatory load. The molecules that can be retrieved in the perfusate might be the expression of a previous or ongoing biological damage or themselves sustain lung injury. A dynamic picture of the biological effects of the CIT and the degree of lung injury that occurred before organ retrieval may be obtained. Implementing the standard EVLP evaluation with a panel of biomarkers specific for the different stages of cell and tissue injury, might help in defining a peculiar biological signature for the single organ. This would be possible only with the availability of faster, standardised and reliable multi-parametric point of care tools. Lung assessment would then benefit from this upgrade under two perspectives: first, identifying - and discarding - organs with an unacceptable risk for early complications, such as high grade PGD and eventually death. Second, EVLP would become a platform for targeted treatments to a molecular level, to heal and recover lungs by acting on one or more mechanisms of the IRI injury cascade.

The Toronto Lung score is the only available and validated score that takes into consideration a point-of-care evaluation of pro-inflammatory CKs levels in EVLP perfusate; however, the analysis is restricted to IL6 and IL8 and does not account for the entire cascade that underlies lung injury [10, 17, 20]. This might not be enough. In fact, gene expression profiling on lung tissue has shown that whereas the inflammatory pathways are upregulated in DBD lungs, cell death, apoptosis, and necrosis predominate in the transcriptomic signature of DCD donors’ lungs [43].

This is the first study to summarise the current research about the predictive and prognostic role of IRI biomarkers measured during EVLP in a systematic and quantitative fashion. We employed a robust statistical method (namely - multilevel meta-analysis), which accounts for effect sizes. In addition, limiting the research to EVLP reduces the confounders that would have been generated including studies considering the donor lungs before the retrieval and/or in the recipient. In the first case the levels of the measured biomarkers are the result of a complex interaction between the multi-organ derangement following brain or cardiac death and of the interplay between lungs and the other organs. Additionally, because CIT has not yet occurred, its contribution to lung injury would not be measured. Conversely, the recipient faces the donor’s inflammatory load, together with the activation of the immune system and the effects of immune suppression, in a context of an end-stage pulmonary disease with potential multi-organic involvement. Another strength of this meta-analysis is that normothermic acellular EVLP is performed in few highly specialized centres in the world and even less ones collected and published their results. This guarantees that the procedures are homogenous, with similar learning curves and few deviations from the original protocols, making measurements highly comparable.

This study has some limitations. Firstly, the small number of studies limits the analysis to a pooled one and does not allow for molecule-by-molecule analysis. Therefore, the overall sample size is small and there is possible overlap of patients, because the same group might have measured different biomarkers on the same specimens. Secondly, it was not possible to compare directly across different studies due to their limited numbers. However, we mitigated this issue by using standardized mean differences to group molecules with similar biological significance, ensuring that all the biomarkers measure the same checkpoint in the inflammatory cascade but employing different scales [22]. Thirdly, the papers included comprise a long period of time and refer to specimen acquired in an even broader time span. In any case, normothermic acellular EVLP technology has not changed much over the past 15 years, and many studies refer to lung assessments performed from about the same period. Fourthly, we attempted to analyse the distribution of true effect sizes with the mean (θi,j), considering all possible sources of heterogeneity. Despite conducting a meticulous analysis, we consistently observed high levels of heterogeneity, particularly between-studies. Considering the incorporation of prediction intervals in our results - providing a range to anticipate the effects of future studies based on current evidence - we posit that our findings might not attain statistical significance in the future, especially with the potential expansion of the sample or exploration of different biomarkers. This underscores the need to prioritize our focus on specific biomarkers. Fifth, most of the studies were of a retrospective nature, using prospectively collected materials, thus limiting the availability of data in terms of laboratory test results. Lastly, our prediction intervals, which can estimate between-study heterogeneity variance and the standard error of the pooled effect, suggest that our results may be subject to confirmation or revision by future studies, as the overall estimated effect is not statistically significant.

Conclusion

Lung perfusate concentration of inflammatory biomarkers, in particular chemokines, are associated with Grade 3 PGD development at 72 h in recipients of EVLP lungs. Future multicentre, prospective observational studies are needed to confirm the results of this meta-analysis.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author Contributions

AC: study design, data interpretation and manuscript writing and revision. EB: study design, data interpretation and analysis and manuscript writing and revision. MM: data interpretation and manuscript revision. ES: data interpretation and manuscript revision. AB: data interpretation and manuscript revision. MR: data interpretation and manuscript revision. LB: data interpretation and manuscript revision. MB: data interpretation and manuscript revision. VF: study design, data interpretation, manuscript writing and revision. All the authors approved the final version of the manuscript to be published and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. The authors received support for the publication of the article from the University of Turin.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our gratitude to Dr. Shaf Keshavjee and Dr. Andrew T. Sage for their invaluable support and generosity in sharing their data, which was instrumental in the inclusion of their study in this meta-analysis.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontierspartnerships.org/articles/10.3389/ti.2025.13794/full#supplementary-material

Footnotes

References

1. Cypel, M, Yeung, JC, Liu, M, Anraku, M, Chen, F, Karolak, W, et al. Normothermic Ex Vivo Lung Perfusion in Clinical Lung Transplantation. N Engl J Med (2011) 364(15):1431–40. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1014597

2. Chao, BT, McInnis, MC, Sage, AT, Yeung, JC, Cypel, M, Liu, M, et al. A Radiographic Score for Human Donor Lungs on Ex Vivo Lung Perfusion Predicts Transplant Outcomes. J Heart Lung Transpl (2024) 43:797–805. doi:10.1016/j.healun.2024.01.004

3. Ayyat, KS, Okamoto, T, Niikawa, H, Sakanoue, I, Dugar, S, Latifi, SQ, et al. A CLUE for Better Assessment of Donor Lungs: Novel Technique in Clinical Ex Vivo Lung Perfusion. J Heart Lung Transpl Off Publ Int Soc Heart Transpl (2020) S1053-2498(20):31665-X. doi:10.1016/j.healun.2020.07.013

4. Costamagna, A, Steinberg, I, Simonato, E, Massaro, C, Filippini, C, Rinaldi, M, et al. Clinical Performance of Lung Ultrasound in Predicting Graft Outcome During Ex Vivo Lung Perfusion. Minerva Anestesiol (2021) 16. doi:10.23736/s0375-9393.21.15527-0

5. Mazzeo, AT, Fanelli, V, Boffini, M, Medugno, M, Filippini, C, Simonato, E, et al. Feasibility of Lung Microdialysis to Assess Metabolism During Clinical Ex Vivo Lung Perfusion. J Heart Lung Transpl (2018) 38:267–76. doi:10.1016/j.healun.2018.12.015

6. Snell, GI, Yusen, RD, Weill, D, Strueber, M, Garrity, E, Reed, A, et al. Report of the ISHLT Working Group on Primary Lung Graft Dysfunction, Part I: Definition and Grading—A 2016 Consensus Group Statement of the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation. J Heart Lung Transpl (2017) 36(10):1097–103. doi:10.1016/j.healun.2017.07.021

7. Christie, JD, Bellamy, S, Ware, LB, Lederer, D, Hadjiliadis, D, Lee, J, et al. Construct Validity of the Definition of Primary Graft Dysfunction After Lung Transplantation. J Heart Lung Transpl (2010) 29(11):1231–9. doi:10.1016/j.healun.2010.05.013

8. Diamond, JM, Arcasoy, S, Kennedy, CC, Eberlein, M, Singer, JP, Patterson, GM, et al. Report of the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation Working Group on Primary Lung Graft Dysfunction, Part II: Epidemiology, Risk Factors, and Outcomes—A 2016 Consensus Group Statement of the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation. J Heart Lung Transpl (2017) 36(10):1104–13. doi:10.1016/j.healun.2017.07.020

9. Prekker, ME, Nath, DS, Walker, AR, Johnson, AC, Hertz, MI, Herrington, CS, et al. Validation of the Proposed International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation Grading System for Primary Graft Dysfunction After Lung Transplantation. J Heart Lung Transpl (2006) 25(4):371–8. doi:10.1016/j.healun.2005.11.436

10. de Perrot, M, Liu, M, Waddell, TK, and Keshavjee, S. Ischemia-Reperfusion-Induced Lung Injury. Am J Respir Crit Care Med (2003) 167(4):490–511. doi:10.1164/rccm.200207-670SO

11. Hsieh, PC, Wu, YK, Yang, MC, Su, WL, Kuo, CY, and Lan, CC. Deciphering the Role of Damage-Associated Molecular Patterns and Inflammatory Responses in Acute Lung Injury. Life Sci (2022) 305:120782. doi:10.1016/j.lfs.2022.120782

12. Kanou, T, Nakahira, K, Choi, AM, Yeung, JC, Cypel, M, Liu, M, et al. Cell-Free DNA in Human Ex Vivo Lung Perfusate as a Potential Biomarker to Predict the Risk of Primary Graft Dysfunction in Lung Transplantation. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg (2021) 162(2):490–9.e2. doi:10.1016/j.jtcvs.2020.08.008

13. Kuipers, MT, van der Poll, T, Schultz, MJ, and Wieland, CW. Bench-to-Bedside Review: Damage-Associated Molecular Patterns in the Onset of Ventilator-Induced Lung Injury. Crit Care (2011) 15(6):235. doi:10.1186/cc10437

14. Monjezi, M, Jamaati, H, and Noorbakhsh, F. Attenuation of Ventilator-Induced Lung Injury Through Suppressing the Pro-Inflammatory Signaling Pathways: A Review on Preclinical Studies. Mol Immunol (2021) 135:127–36. doi:10.1016/j.molimm.2021.04.007

15. Tolle, LB, and Standiford, TJ. Danger-Associated Molecular Patterns (DAMPs) in Acute Lung Injury. J Pathol (2013) 229(2):145–56. doi:10.1002/path.4124

16. Chacon-Alberty, L, Fernandez, R, Jindra, P, King, M, Rosas, I, Hochman-Mendez, C, et al. Primary Graft Dysfunction in Lung Transplantation: A Review of Mechanisms and Future Applications. Transplantation (2023) 107(8):1687–97. doi:10.1097/TP.0000000000004503

17. Barnett, N, and Ware, LB. Biomarkers in Acute Lung Injury—Marking Forward Progress. Crit Care Clin (2011) 27(3):661–83. doi:10.1016/j.ccc.2011.04.001

18. Blankenberg, S, Rupprecht, HJ, Bickel, C, Peetz, D, Hafner, G, Tiret, L, et al. Circulating Cell Adhesion Molecules and Death in Patients With Coronary Artery Disease. Circulation (2001) 104(12):1336–42. doi:10.1161/hc3701.095949

19. Hashimoto, K, Cypel, M, Kim, H, Machuca, TN, Nakajima, D, Chen, M, et al. Soluble Adhesion Molecules During Ex Vivo Lung Perfusion Are Associated With Posttransplant Primary Graft Dysfunction. Am J Transpl (2017) 17(5):1396–404. doi:10.1111/ajt.14160

20. Sage, AT, Richard-Greenblatt, M, Zhong, K, Bai, XH, Snow, MB, Babits, M, et al. Prediction of Donor Related Lung Injury in Clinical Lung Transplantation Using a Validated Ex Vivo Lung Perfusion Inflammation Score. J Heart Lung Transpl (2021) 40(7):687–95. doi:10.1016/j.healun.2021.03.002

21. Moher, D, Liberati, A, Tetzlaff, J, and Altman, DG, The PRISMA Group. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. Plos Med (2009) 6(7):e1000097. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097

22. Higgins, JPT, and Green, S (Editors). Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.1.0 [updated March 2011]. The Cochrane Collaboration (2011). Available at: www.handbook.cochrane.org.

23. Bailey, JG, Morgan, CW, Christie, R, Ke, JXC, Kwofie, MK, and Uppal, V. Continuous Peripheral Nerve Blocks Compared to Thoracic Epidurals or Multimodal Analgesia for Midline Laparotomy: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Korean J Anesthesiol (2021) 74(5):394–408. doi:10.4097/kja.20304

24. Ouzzani, M, Hammady, H, Fedorowicz, Z, and Elmagarmid, A. Rayyan—A Web and Mobile App for Systematic Reviews. Syst Rev (2016) 5(1):210. doi:10.1186/s13643-016-0384-4

25. Sterne, JA, Hernán, MA, Reeves, BC, Savović, J, Berkman, ND, Viswanathan, M, et al. ROBINS-I: A Tool for Assessing Risk of Bias in Non-Randomised Studies of Interventions. BMJ (2016) 12:i4919. doi:10.1136/bmj.i4919

26. McGuinness, LA, and Higgins, JPT. Risk-of-Bias VISualization (Robvis): An R Package and Shiny Web App for Visualizing Risk-of-Bias Assessments. Res Synth Methods (2021) 12(1):55–61. doi:10.1002/jrsm.1411

27. Harrer, M. Doing Meta-Analysis With R: A Hands-On Guide. New York, NY. Chapman & Hall/CRC Press (Taylor & Francis) (2021). doi:10.1201/9781003107347

28. IntHout, J, Ioannidis, JPA, Rovers, MM, and Goeman, JJ. Plea for Routinely Presenting Prediction Intervals in Meta-Analysis. BMJ Open (2016) 6(7):e010247. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2015-010247

29. R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment F Statistical Computing. Vienna, Austria (2023). Available from: https://www.R-project.org/ (Accessed November 2024).

30. Machuca, TN, Cypel, M, Zhao, Y, Grasemann, H, Tavasoli, F, Yeung, JC, et al. The Role of the Endothelin-1 Pathway as a Biomarker for Donor Lung Assessment in Clinical Ex Vivo Lung Perfusion. J Heart Lung Transpl (2015) 34(6):849–57. doi:10.1016/j.healun.2015.01.003

31. Boffini, M, Marro, M, Simonato, E, Scalini, F, Costamagna, A, Fanelli, V, et al. Cytokines Removal during Ex-Vivo Lung Perfusion: Initial Clinical Experience. Transpl Int (2023) 36:10777. doi:10.3389/ti.2023.10777

32. Brenckmann, V, Briot, R, Ventrillard, I, Romanini, D, Barbado, M, Jaulin, K, et al. Continuous Endogenous Exhaled CO Monitoring by Laser Spectrometer in Human EVLP Before Lung Transplantation. Transpl Int (2022) 35:10455. doi:10.3389/ti.2022.10455

33. Hashimoto, K, Cypel, M, Juvet, S, Saito, T, Zamel, R, Machuca, TN, et al. Higher M30 and High Mobility Group Box 1 Protein Levels in Ex Vivo Lung Perfusate Are Associated With Primary Graft Dysfunction After Human Lung Transplantation. J Heart Lung Transpl (2018) 37(2):240–9. doi:10.1016/j.healun.2017.06.005

34. Machuca, TN, Cypel, M, Yeung, JC, Bonato, R, Zamel, R, Chen, M, et al. Protein Expression Profiling Predicts Graft Performance in Clinical Ex Vivo Lung Perfusion. Ann Surg (2015) 261(3):591–7. doi:10.1097/SLA.0000000000000974

35. Capuzzimati, M, Hough, O, and Liu, M. Cell Death and Ischemia-Reperfusion Injury in Lung Transplantation. J Heart Lung Transpl (2022) 41(8):1003–13. doi:10.1016/j.healun.2022.05.013

36. Del, SL, Costamagna, A, Muraca, G, Rotondo, G, Civiletti, F, Vizio, B, et al. Intratracheal Administration of Small Interfering RNA Targeting Fas Reduces Lung Ischemia-Reperfusion Injury. Crit Care Med (2016) 44(8):e604–13. doi:10.1097/CCM.0000000000001601

37. Hoffman, SA, Wang, L, Shah, CV, Ahya, VN, Pochettino, A, Olthoff, K, et al. Plasma Cytokines and Chemokines in Primary Graft Dysfunction Post-Lung Transplantation. Am J Transpl Off J Am Soc Transpl Am Soc Transpl Surg. (2009) 9(2):389–96. doi:10.1111/j.1600-6143.2008.02497.x

38. Baran, CP, Opalek, JM, McMaken, S, Newland, CA, O’Brien, JM, Hunter, MG, et al. Important Roles for Macrophage Colony-Stimulating Factor, CC Chemokine Ligand 2, and Mononuclear Phagocytes in the Pathogenesis of Pulmonary Fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med (2007) 176(1):78–89. doi:10.1164/rccm.200609-1279OC

39. Quartuccio, L, Fabris, M, Sonaglia, A, Peghin, M, Domenis, R, Cifù, A, et al. Interleukin 6, Soluble Interleukin 2 Receptor Alpha (CD25), Monocyte Colony-Stimulating Factor, and Hepatocyte Growth Factor Linked With Systemic Hyperinflammation, Innate Immunity Hyperactivation, and Organ Damage in COVID-19 Pneumonia. Cytokine (2021) 140:155438. doi:10.1016/j.cyto.2021.155438

40. Müller, AM, Cronen, C, Müller, KM, and Kirkpatrick, CJ. Heterogeneous Expression of Cell Adhesion Molecules by Endothelial Cells in ARDS. J Pathol (2002) 198(2):270–5. doi:10.1002/path.1186

41. Calfee, CS, Eisner, MD, Parsons, PE, Thompson, BT, Conner, ER, Matthay, MA, et al. Soluble Intercellular Adhesion Molecule-1 and Clinical Outcomes in Patients With Acute Lung Injury. Intensive Care Med (2009) 35(2):248–57. doi:10.1007/s00134-008-1235-0

42. Reutershan, J, and Ley, K. Bench-to-Bedside Review: Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome – How Neutrophils Migrate Into the Lung. Crit Care (2004) 8(6):453–61. doi:10.1186/cc2881

43. Baciu, C, Sage, A, Zamel, R, Shin, J, Bai, XH, Hough, O, et al. Transcriptomic Investigation Reveals Donor-Specific Gene Signatures in Human Lung Transplants. Eur Respir J (2021) 57(4):2000327. doi:10.1183/13993003.00327-2020

Glossary

PGD primary graft dysfunction

ICU intensive care unit

Ltx lung transplantation

PaO2 partial pressure of arterial oxygen

FiO2 fraction of inspired oxygen

IRI ischemia reperfusion injury

CIT cold ischemic time

DAMPs damage-associated molecular patterns

EVLP Ex vivo lung perfusion

TLS2 Toronto Lung Score 2

RCTs randomized controlled trials

NRCTs non-randomized controlled trials

PRISMA Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses

ROBINS-i Risk Of Bias In Non-randomized Studies–of Interventions

sE-selectin serum E selectin

sICAM soluble intercellular adhesion molecule-1

vCAM soluble adhesion molecules vascular cell adhesion molecule-1

ET-1 endothelin-1

Big ET-1 big endothelin-1

IL8 Interleukin 8

MCP monocyte chemotactic protein

GROα growth-regulated oncogene α

MIP-1a macrophage inflammatory protein 1a

MIP-1b macrophage inflammatory protein 1b

IL1β Interleukin 1β

IL6 Interleukin 6

TNFα tumour necrosis factor α

HMGB High mobility group box 1

nuDNA nuclear DNA

mtDNA mitochondrial DNA

M-CSF macrophage colony-stimulating factor

G-CSF Granulocyte colony-stimulating factor

CO carbon monoxide

NOx nitric oxide metabolite

TLR Toll-like receptor

Keywords: ex vivo lung perfusion, ischemia-reperfusion injury, primary graft dysfunction, inflammation, biomarkers

Citation: Costamagna A, Balzani E, Marro M, Simonato E, Burello A, Rinaldi M, Brazzi L, Boffini M and Fanelli V (2025) Association of Inflammatory Profile During Ex Vivo Lung Perfusion With High-Grade Primary Graft Dysfunction: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Transpl Int 38:13794. doi: 10.3389/ti.2025.13794

Received: 12 September 2024; Accepted: 02 January 2025;

Published: 29 January 2025.

Copyright © 2025 Costamagna, Balzani, Marro, Simonato, Burello, Rinaldi, Brazzi, Boffini and Fanelli. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Andrea Costamagna, YW5kcmVhLmNvc3RhbWFnbmFAdW5pdG8uaXQ=

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

Andrea Costamagna

Andrea Costamagna Eleonora Balzani1†

Eleonora Balzani1† Matteo Marro

Matteo Marro Alessandro Burello

Alessandro Burello Luca Brazzi

Luca Brazzi Massimo Boffini

Massimo Boffini