- 1Molecular and Human Genetics Laboratory, Department of Zoology, University of Lucknow, Lucknow, India

- 2Department of Personalized and Molecular Medicine, Era University, Lucknow, India

- 3Department of Radiotherapy, All India Institute of Medical Sciences, Nagpur, India

- 4Department of Radiotherapy, King George’s Medical University, Lucknow, India

Background: Evidences suggest that single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) can be considered as potential biomarkers for disease progression and therapeutic response in cervical cancer. The present study investigated the association of CYP1A1 T>C (rs4646903), CYP1A1 A>G (rs1048943), CYP2E1 T>A (rs6413432), RAD51 G>C (rs1801320), XRCC1 G>A (rs25487), XRCC2 G>A (rs3218536) and XRCC3 C>T (rs861539) polymorphisms with treatment outcome of cisplatin based chemoradiation (CRT).

Methods: Total 227 cervical cancer cases, treated with the same chemoradiotherapy regimen were selected for the study. Genotyping analysis was performed by PCR-restriction fragment length polymorphisms (PCR-RFLP). Treatment response was evaluated by Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST). Association of all clinical data (responses, recurrence and survival of patients) and single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) was analysed by using SPSS (version 21.0).

Results: Patients with TA/AA genotype of CYP2E1 T>A polymorphism showed significantly poor response while those with GC/CC genotype of RAD51 G>C showed better response (p = 0.008, p = 0.014 respectively). Death was significantly higher in patients with GG genotypes of RAD51 G>C and XRCC1 G>A (p = 0.006, p = 0.002 respectively). Women with GC+CC genotype of RAD51 G>C and AG+GG of XRCC1 showed better survival and also reduced risk of death (HR = 0.489, p = 0.008; HR = 0.484, p = 0.003 respectively).

Conclusion: Results suggested that CYP2E1 T>A (rs6413432), RAD51 G>C (rs1801320), and XRCC1 G>A (rs25487) polymorphisms may be used as predictive markers for clinical outcomes in cervical cancer patients undergoing cisplatin based concomitant chemoradiotherapy.

Introduction

Cervical cancer is the most common cancer among women all over the world and majority of cases are diagnosed at advanced stage (1, 2). In early stage of cervical cancer, surgery and radiation therapy are equally effective, but for patients with advanced stage, chemoradiotherapy is the preferred mode of treatment (3). A varied outcome after chemoradiotherapy is observed in cervical cancer patients, these varied responses in individuals are often due to differences in their genetic constitution (4). Ionizing radiations induces DNA damage, including double strand DNA breaks (DSBs), Single-strand DNA breaks (SSBs) and DNA-DNA crosslinks while platinum compounds such as cisplatin forms cisplatin-DNA adducts (5, 6). These lesions are repaired by multiple repair pathways, homologous recombination (HR), non-homologous end-joining (NHEJ), base excision repair (BER), nucleotide excision repair (NER) and if repaired inadequately lead to cell death and increasing radiation sensitivity.

Genetic polymorphisms in CYP and DNA repair genes are associated with differential repair activities and may explain inter-individual differences in treatment response influencing clinical outcome (7–9). Polymorphisms in these DNA repair genes can modulate their total repair capacity as well as influence the removal of platinum-DNA adducts, persistence of which underpins the antitumor potential of chemoradiation (10, 11). RAD51 plays an important role in homologous recombination (HR) repair of DNA during DSBs damage caused by ionising radiation and alkylating agents (12). RAD51 G172T polymorphism showed association with overall survival of cervical cancer patients treated with chemoradiotherapy (CRT) (2). XRCC1 plays critical role in both BER and single-stranded break repair (SSBR) processes and removes oxidative DNA damage caused by exposures to ionizing radiation or alkylating agents like cisplatin (13). Higher XRCC1 expression is associated with poor response and survival, particularly in patients with head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC) receiving chemoradiation (14). DNA repair gene polymorphisms, particularly XRCC1 Arg399Gln, may modify the response to gemcitabine-platinum combination chemotherapy (15). The XRCC3-241Thr/Thr genotype was associated with adverse progression-free survival of colorectal cancer patients (16).

A clear understanding of the molecular genetics of cervical cancer is necessary to deduce new therapeutic strategies that will benefit patients suffering from the disease. In this study, we have investigated the role of different genetic polymorphisms viz. CYP1A1 T>C (rs4646903), CYP1A1 A>G (rs1048943), CYP2E1 T>A (rs6413432), RAD51 G>C (rs1801320), XRCC1 G>A (rs25487), XRCC2 G>A (rs3218536) and XRCC3 C>T (rs861539) in the treatment outcome of cisplatin based chemoradiation in cervical cancer patients.

Methods and Materials

The patients prescribed for cisplatin based concomitant chemoradiation (CRT) treatment were recruited for this study from the Departments of Radiotherapy and Obstetrics and Gynecology, King George’s Medical University (KGMU), Lucknow, India. The recruited women were with no associated co-morbid conditions and had received no previous radiation or chemotherapy. Demographic and clinical characteristics of patients were obtained from medical records while staging and clinical diagnosis of patients were performed by expert clinicians as per guidelines of International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) 2009. Samples were collected after informed consent of all study subjects and approval of Institutional Ethics Committee of KGMU, Lucknow (No.274/R.Cell-10). Five milliliters venous blood samples were obtained from 244 subjects for genotyping study at the start of treatment regimen.

Doses of both therapies (chemotherapy and radiation) were same for all patients. All patients received a total dose of 50 Gy in 25 fractions of pelvic external beam radiotherapy with weekly 40 mg/m2 concomitant cisplatin followed by three applications of high dose rate (HDR) intracavitory brachytherapy (7 Gy/fraction at 1-week interval). The patients who violated the treatment protocol or did not complete the planned chemoradiation dose were excluded from the study. The patient response to treatment was measured by response evaluation criteria in solid tumors (RECIST) version 1.0 after 1 month of treatment. Patients were followed-up after treatment and checked for survival. The primary endpoint was overall survival (OS) observed from the date of diagnosis to the date of death from any cause. Women who were alive at the end of the study were censored.

Genomic DNA was extracted from venous blood by salting out method with slight modification (17). DNA samples were checked by agarose gel electrophoresis. The CYP1A1 T>C (rs4646903), CYP1A1 A>G (rs1048943), CYP2E1 T>A (rs6413432), RAD51 G>C (rs1801320), XRCC1 G>A (rs25487), XRCC2 G>A (rs3218536) and XRCC3 C>T (rs861539) polymorphisms were genotyped by Restriction Fragment Length Polymorphism (PCR-RFLP) by using specific primers (F-5′ACTCACCCTGAACCCCATTC3′, R-5′GGCCCCAACTACTCAGAGGCT3′; F-5′CTGTCTCCCTCTGGTTACAGGAAGC3′, R-5′TTCCACCCGTTGCAGCAGGATAGCC3′; F-5′TCGTCAGTTCCTGAAAGCAGG3′, R-5′GAGCTCTGATGGAAGTATCGCA-3′; F-5′TGGGAACTGCAACTCATCTGG3′, R-5′GCGCTCCTCTCTCCAGCAG3′; F-5′TTGTGCTTTCTCTGTGTCCA3′, R-5′TCCTCCAGCCTTTTCTGATA3′; F-5′TGTAGTCACCCATCTCTCTGC3′, R-5′AGTTGCTGCCATGCCTTACA3′; and F-5′GGTCGAGTGACAGTCCAAAC3′, R-5′CTACCCGCAGGAGCCGGAGG3′, respectively) and specific restriction enzymes (MspI, BsrDI, DraI, BstNI, MspI, HphI and NlaIII).

Demographic and clinical information was correlated with genotypes using χ2 analysis and Fisher’s exact test (for categoric variables) and one-way analysis of variance (for continuous variables). Genotype and overall survivals were evaluated by Kaplan-Meier function and Cox proportional hazards model. Log-rank test was used to detect differences in overall survival across different genotypes. 95% Confidence Intervals (CIs) and Hazard ratios (HRs) were estimated using multivariate Cox proportional hazards model/Cox regression analysis. The regression data was adjusted for age, stage and histopathology. All differences in p values were considered statistically significant for p < .05. All statistical analyses were performed by SPSS (Version 21.0).

Results

Out of 244 cervical cancer patients, 227 were included in the study. Seventeen cases were excluded due to protocol violations. Mean age of patients was 49.0 ± 8.68 years. Histopathologically, 216 patients (95.2%) had squamous cell carcinoma and remaining 11 (4.8%) had adenocarcinoma. Squamous cell carcinoma was distributed into three categories: 96 well (44.4%), 79 moderate (36.6%) and 21 poor (9.7%) while no differentiation was reported in 20 cases (9.3%). The staging of tumor according to FIGO was 117 cases (51.5%) with stage IIB and 110 (48.5%) with stage IIIA+IIIB (Table 2). Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST) was used to assess treatment response as complete response (CR), partial response (PR), stable disease (SD) and progressive disease (PD). CR and PR were considered as responders while SD and PD as non-responders.

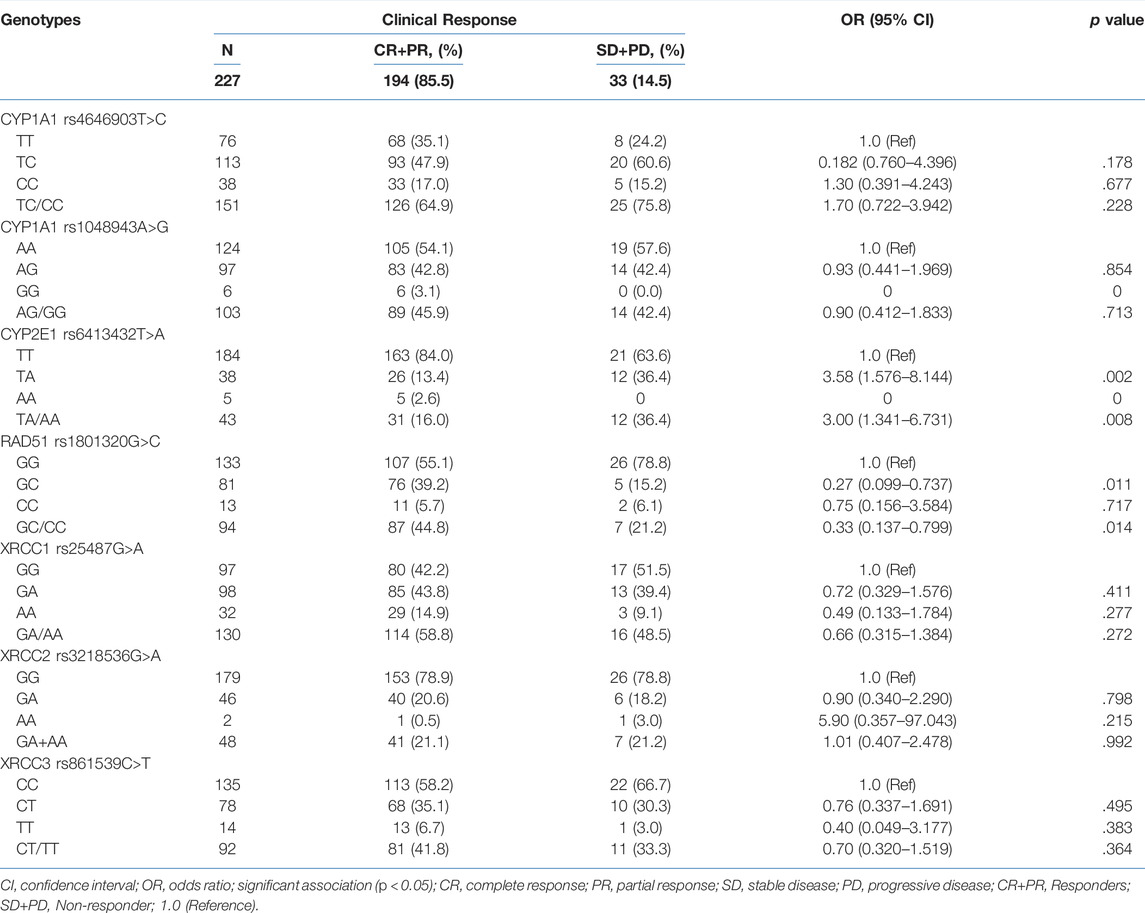

The distribution of CYP1A1 T>C rs4646903 genotypes showed 33.5% cases with TT and 66.5% with TC/CC while distribution of CYP1A1 A>G rs1048943 showed 54.6% cases with AA and 45.4% with AG/GG. The distribution of CYP2E1 T>A rs6413432 genotypes showed 81.1% cases with TT, 18.9% with TA/AA. The distribution of RAD51 G>C rs1801320 genotypes showed 58.6% cases with GG and 41.4% with GC/CC while distribution of XRCC1 G>A rs3218536 showed 42.7% cases with GG and 57.3% with GA/AA. The XRCC2 G>A rs3218536 genotypes showed 78.9% cases with GG, 21.1% with GA/AA. However, distribution of XRCC3 C>T rs861539 showed 59.5% cases with CC genotypes and 40.5% with CT/TT genotypes. The significant differences in treatment response were found for CYP2E1 T>A rs6413432, but not for CYP1A1 T>C rs4646903 and A>G rs1048943 polymorphisms. The cases with TA genotype of CYP2E1 T>A rs6413432 polymorphism showed significant decrease in treatment response when compared to those with TT genotype (36.4 vs 13.4%, p = .002). In case of RAD51 G>C rs1801320, homozygous GG genotype had a significantly bad response when compared with GC genotype (55.2 vs 78.8%; p = .011) and same results were found with CC genotype but no statistical significance (5.7 vs 6.1%; p = .717). In case of XRCC1 G>A rs25487, XRCC2 G>A rs3218536 and XRCC3 C>T rs861539, we did not observe any significant association (p > .05, Table 1).

TABLE 1. Association of genotypes of CYP1A1 T>C rs4646903, CYP1A1 A>G rs1048943, CYP2E1 T>A rs6413432, RAD51 G>C rs1801320, XRCC1 G>A, rs25487 XRCC2 G>A rs3218536 and XRCC3 C>T rs861539 polymorphisms with clinical response of cervical cancer cases (n = 227).

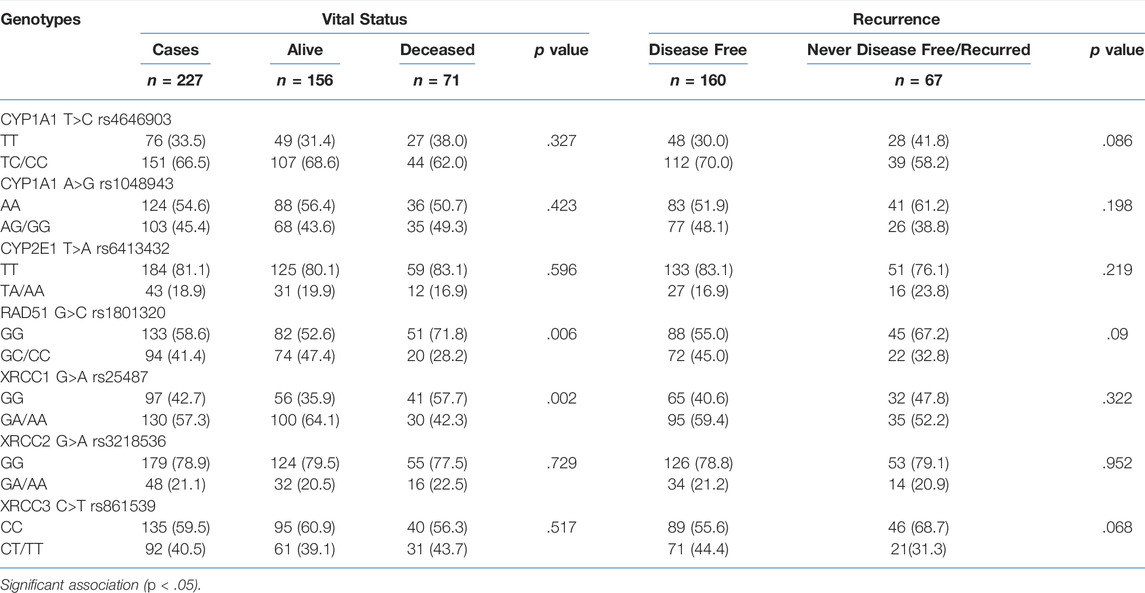

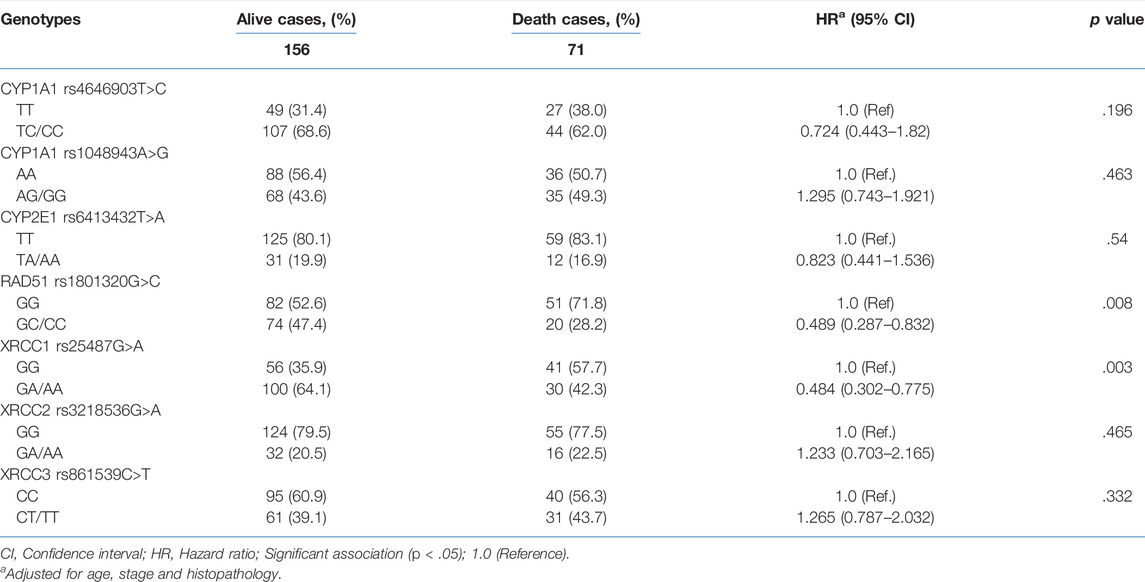

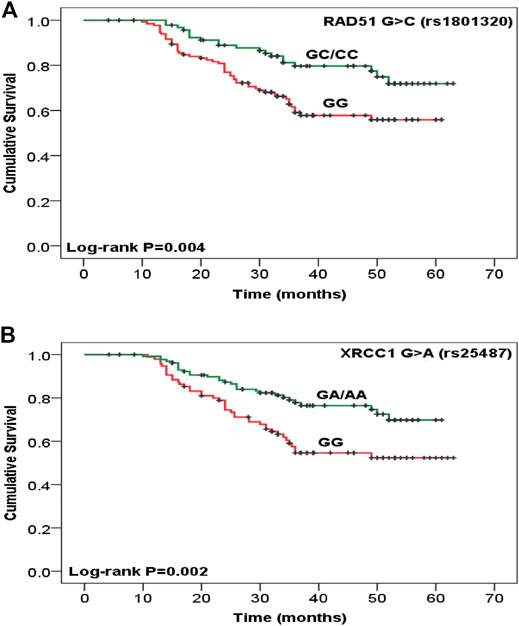

Disease recurrence was significantly decreased in women with TA/AA genotypes of CYP2E1 T>A rs6413432 (p = .016) but CYP1A1 T>C rs4646903 and A>G rs1048943 polymorphisms did not show any association (Table 2). Most of the cases with GC+CC genotypes of RAD51 G>C rs1801320 and GA/AA genotypes of XRCC1 G>A rs25487 were found to be alive at the end of study period (p = .006 and p = .002, respectively) while none with XRCC2 G>A rs3218536 and XRCC3 C>T rs861539 genotypes exhibited similar response. The risk of recurrence was significantly reduced in GA/AA genotypes of XRCC1 G>A rs25487 (p = .025) (Table 2). The median follow-up duration for all cases was 34 months (range, 4.2–63.0 months). During the study period (2009–2011), 31.3% cases succumbed to death. Association of genotypes with overall survival as analysed by Cox proportional hazards model (HR), adjusted for age, stage and histopathology is shown in Table 3. There was significant reduction in hazard of death (HR = 0.489) among women with GC/CC genotypes of RAD51 G>C rs1801320 when compared with women having GG genotype and HR = 0.484 with GA/AA genotypes of XRCC1 G>A rs25487 when compared with women having AA genotype (p = .008 and p = .003 respectively) (Table 3). The Kaplain-Meier function and Log rank test for survival in cases with genotypes are shown in Figures 1A,B. There was no association with the CYP1A1 A>G rs1048943 and CYP2E1 T>A rs6413432 genotypes. The GC+CC genotype of RAD51 G>C rs1801320 and GA/AA genotype of XRCC1 G>A rs25487 were associated with better overall survival (log-rank, p = .004 and p = .002 respectively) (Figures 1A,B). There was no association with XRCC2 G>A rs3218536 and XRCC3 C>T rs861539 polymorphisms.

TABLE 2. Association of genotypes of CYP1A1 T>C rs4646903, CYP1A1 A>G rs1048943, CYP2E1 T>A rs6413432, RAD51 G>C rs1801320, XRCC1 G>A, rs25487 XRCC2 G>A rs3218536 and XRCC3 C>T rs861539 polymorphisms with vital status and recurrence of cervical cancer cases (n = 227).

TABLE 3. Association of genotypes of CYP1A1 T>C rs4646903, CYP1A1 A>G rs1048943, CYP2E1 T>A rs6413432, RAD51 G>C rs1801320, XRCC1 G>A rs25487, XRCC2 G>A rs3218536 and XRCC3 C>T rs861539 polymorphisms and survival after treatment (CRT) for cervical cancer.

FIGURE 1. Kaplan-Meier function for overall survival after chemoradiotherapy treatment among cervical cancer patients with (A) RAD51 G>C rs1801320, GG vs. GC/CC (n = 133 vs. 94) and (B) XRCC1 G>A rs25487, GG vs. GA/AA (n = 97 vs. 130) genotypes. Test for survival difference by log- rank methods.

Discussion

Cisplatin based concomitant chemoradiation is the standard treatment of locally advanced cervical cancer (2). However, primary or acquired chemoradioresistance is a serious clinical problem that contributes to disease recurrence, progression and mortality (18). Poor response and high inter-individual variations in treatment response occurs among patients. Local and distant metastasis occurs due to the survival of some tumor cells leading to treatment failure. Therefore, new and more effective approaches are required to tackle this issue. The mechanisms of these heterogeneous responses to treatment are multifactorial and involve variability in genetic constitution (19).

Members of Xenobiotic metabolizing enzymes (XMEs) are CYP1A1, CYP1B1, CYP2D6, CYP2E1, mEH, NAT1 etc, which demonstrate their anti-neoplastic effects by producing reactive oxygen species (ROS) whose cytotoxic effects cause tumor cell death and are likely to impact the treatment efficacy as well as survival after treatment (20, 21). CYP1A1 and CYP2E1 are the important members of XME family and have been extensively studied as biomarkers for cancer risk prediction. Significant association of CYP1A1 m2 (rs1048943) polymorphism with platinum drugs (e.g. Cisplatin) was observed, which represent an important class of anticancer agents and are frequently used in treatment of various types of solid cancers including cervical cancer (22, 23). In the present study, cases with homozygous TT/AA genotype of CYP2E1 T>A rs7632 polymorphism showed poor treatment response as compared to heterozygous TT genotype with significant association (p = .002, Table 3). No association of CYP1A1 (CYP1A1 rs4646903, CYP1A1 rs1048943 and CYP2E1 T>A rs7632) polymorphisms was found with survival of cervical cancer patients treated with cisplatin based chemoradiation.

Radiotherapy and chemotherapy destroy cancer cells by inducing DNA damage. So, the treatment outcome may be dependent on DNA repair systems (24). It is known that ionizing radiation (IR) can damage DNA, producing single and double-strand breaks on DNA, as well as an indirect effect by generating reactive oxygen species (ROSs) in the cells (25). The DNA repair capacity of individuals consists of several pathways: nucleotide and base excision repair (BER), homologous recombination (HR), end joining, and telomere metabolism. BER of single-strand breaks and homologous repair of double-strand breaks (DSBs) are considered the most important pathways in repair of radiation-induced DNA damage (26). Many studies confirmed that genetic polymorphisms in DNA repair genes are associated with differential treatment outcomes of Chemoradiotherapy (9). Human RAD51 is required for meiotic/mitotic recombination and plays an important role in homology-dependent recombinational repair of DSBs, caused by ionizing radiation and alkylating agents (12). RAD172 G>T (rs1801321) polymorphism has been associated with altered gene transcription (27). RAD51 expression is an independent predictor for tumor progression as well as tumor recurrence (2). In the present study, response of treatment was significantly higher (p < .05) in individuals with “C” allele of RAD51 G>C rs1801320 polymorphism (Table 1). A reduced hazard of death and better overall survival was observed among CRT treated women with GC/CC genotypes of RAD51 G>C rs1801320 (p = .008, p = .004 respectively) (Figure 1A; Table 3). The individuals with GC/CC genotypes of RAD51 G>C rs1801320 were alive for a longer period of time as compared to those with GG genotype at the end of study period (p = .006) (Table 2). X-Ray repair cross complementing group 1 (XRCC1) is a base excision repair (BER) protein that plays an important role in single-strand breaks repair (SSBR), DSBs repair, BER and following exposure to endogenous reactive oxygen species. XRCC1 deficiency results in hypersensitivity to chemoradiation. XRCC1 R399Q polymorphism is a well-studied single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) located in the BRCT1 domain and have been found to influence treatment response (25, 28). Two survival studies in ovarian cancer were conducted in Korea and Russia where no significant association was found with XRCC1 +399 G>A (rs25487) polymorphism (29, 30). According to Miao et al. (31), individuals with AA genotype of XRCC1 +399G>A polymorphism had a significant risk of death from ovarian cancer. Other studies have shown association of XRCC1 with survival and/or risk in non-small-cell lung cancer, colorectal and laryngeal squamous cell cancer (9, 32). According to our results, occurrence of death was significantly reduced among patients having GA/AA genotypes of XRCC1 +399 G>A (p = 0.002). Most of the cases with GA/AA genotype of XRCC1 +399G>A were found to be alive at the end of the study period as compared to cases with AA genotype (p = .003) (Figure 1B). XRCC2 is one of the main components of RAD51-related protein family required for correct chromosome segregation and apoptotic response to DSBs (33). The G>A (rs3218536) polymorphism of XRCC2 was an independent prognostic factor for overall survival in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) cases treated with definitive radiotherapy (34). In pancreatic cancer, the AA genotype of XRCC2 G>A rs3218536 was associated with a significantly shorter survival than the GG/GA genotype (35). High expression of XRCC3 in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC) is associated with chemoradiotherapy resistance and predicts poor survival in patients (36). According to Bewick et al (2006) survival of breast cancer patients was higher in women having XRCC3 C>T rs18067 polymorphism (37). In present study, no association of XRCC2 rs3218536G>A and XRCC3 rs861539C>T polymorphisms was observed with treatment outcome in cervical cancer patients.

In this study, we have focused on the effect of genetics on inter-individual differences in response to DNA damaging agents. The differential activity of cytochrome P-450 and DNA repair enzymes have an impact on treatment outcome of individual patients. Therefore, this kind of study may help clinicians to alter treatment strategies for cervical cancer patients on a personalized basis.

Summary Table

What is Known About This Subject

• Cisplatin based concomitant chemoradiation is the standard treatment for locally advanced cervical cancer. Poor response and high inter-individual variations in treatment response occurs due to differences in genetic makeup.

• The differential activity of metabolic (e.g., cytochrome P-450) and DNA repair enzymes have an impact on treatment outcome.

• Genetic polymorphisms in metabolic and DNA-repair enzymes contribute to inter-patient variability in treatment response.

What This Paper Adds

• Genetic variants in drug metabolizing and DNA repair genes with treatment outcome of CRT in cervical cancer patients.

• CYP2E1rs6413432, RAD51rs1801320, and XRCC1rs25487 were associated with inter-individual variations in response to chemoradiotion.

• These polymorphisms may act as prognostic biomarkers for prediction of clinical outcome of CRT in cervical cancer patients.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Institutional Ethics Committee of King George’s Medical University, Lucknow, India (No.274/R.Cell-10). The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study. Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author Contributions

Conceived and designed the experiments: MB, KS, MA. Performed the experiments: MA. Analyzed the data: MA, VK. Wrote the paper: MA, VK, MB.

Funding

This work was supported by Council of Science and Technology-Uttar Pradesh (CST-UP) Lucknow, India, Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR) and Department of Science and Technology (DST), New Delhi.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors are thankful to Centre of Excellence Programme of Higher Education, Government of Uttar Pradesh, India, DST-FIST-PURSE is also duly acknowledged for Central Instrumentation Facility at Department of Zoology, University of Lucknow, Lucknow, India. MA is thankful to ICMR for Senior Research Fellowship.

References

1. Denslow, SA, Knop, G, Klaus, C, Brewer, NT, Rao, C, and Smith, JS. Burden of Invasive Cervical Cancer in North Carolina. Prev Med (2012) 54(3–4):270–6. doi:10.1016/j.ypmed.2012.01.020

2. Nogueira, A, Catarino, R, Faustino, I, Nogueira-Silva, C, Figueiredo, T, Lombo, L, et al. Role of the RAD51 G172T Polymorphism in the Clinical Outcome of Cervical Cancer Patients under Concomitant Chemoradiotherapy. Gene (2012) 504:279–83. doi:10.1016/j.gene.2012.05.037

3. Yuan, G, Wu, L, Huang, M, Li, N, and An, J. A Phase II Study of Concurrent Chemo-Radiotherapy with Weekly Nedaplatin in Advanced Squamous Cell Carcinoma of the Uterine Cervix. Radiat Oncol (2014) 9:55–6. doi:10.1186/1748-717X-9-55

4. Candelaria, M, Garcia-Arias, A, Cetina, L, and Dueñas-Gonzalez, A. Radiosensitizers in Cervical Cancer. Cisplatin and beyond. Radiat Oncol (2006) 1:15. doi:10.1186/1748-717x-1-15

5. Jorgensen, TJ. Enhancing Radiosensitivity: Targeting the DNA Repair Pathways. Cancer Biol Ther (2009) 8:665–70. doi:10.4161/cbt.8.8.8304

6. Abdel‐Fatah, T, Sultana, R, Abbotts, R, Hawkes, C, Seedhouse, C, Chan, S, et al. Clinicopathological and Functional Significance of XRCC1 Expression in Ovarian Cancer. Int J Cancer (2013) 132:2778–86. doi:10.1002/ijc.27980

7. Shukla, P, Pant, M, Gupta, D, and Parmar, D. CYP 2D6 Polymorphism: A Predictor of Susceptibility and Response to Chemoradiotherapy in Head and Neck Cancer. J Can Res Ther (2012) 8:40–5. doi:10.4103/0973-1482.95172

8. Huo, R, Tang, K, Wei, Z, Shen, L, Xiong, Y, Wu, X, et al. Genetic Polymorphisms in CYP2E1: Association with Schizophrenia Susceptibility and Risperidone Response in the Chinese Han Population. PLoS One (2012) 7(7):e34809. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0034809

9. Gurubhagavatula, S, Liu, G, Park, S, Zhou, W, Su, L, Wain, JC, et al. XPD and XRCC1 Genetic Polymorphisms Are Prognostic Factors in Advanced Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer Patients Treated with Platinum Chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol (2004) 22:2594–601. doi:10.1200/jco.2004.08.067

10. Au, WW, Salama, SA, and Sierra-Torres, CH. Functional Characterization of Polymorphisms in DNA Repair Genes Using Cytogenetic challenge Assays. Environ Health Perspect (2003) 111:1843–50. doi:10.1289/ehp.6632

11. Jung, Y, and Lippard, SJ. Direct Cellular Responses to Platinum-Induced DNA Damage. Chem Rev (2007) 107:1387–407. doi:10.1021/cr068207j

12. Gachechiladze, M, Škarda, J, Soltermann, A, and Joerger, M. RAD51 as a Potential Surrogate Marker for DNA Repair Capacity in Solid Malignancies. Int J Cancer (2017) 141:1286–94. doi:10.1002/ijc.30764

13. Wong, H-K, and Wilson, DM. XRCC1 and DNA Polymerase β Interaction Contributes to Cellular Alkylating-Agent Resistance and Single-Strand Break Repair. J Cell Biochem. (2005) 95:794–804. doi:10.1002/jcb.20448

14. Ang, M-K, Patel, MR, Yin, X-Y, Sundaram, S, Fritchie, K, Zhao, N, et al. High XRCC1 Protein Expression is Associated with Poorer Survival in Patients with Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res (2011) 17:6542–52. doi:10.1158/1078-0432.ccr-10-1604

15. Erčulj, N, Kovač, V, Hmeljak, J, Franko, A, Dodič-Fikfak, M, and Dolžan, V. DNA Repair Polymorphisms and Treatment Outcomes of Patients with Malignant Mesothelioma Treated with Gemcitabine-Platinum Combination Chemotherapy. J Thorac Oncol (2012) 7:1609–17. doi:10.1097/JTO.0b013e3182653d31

16. Krupa, R, and Blasiak, J. An Association of Polymorphism of DNA Repair Genes XRCC1 and XRCC3 with Colorectal Cancer. J Exp Clin Cancer Res (2004) 23:285–94.

17. Miller, SA, Dykes, DD, and Polesky, HF. A Simple Salting Out Procedure for Extracting DNA from Human Nucleated Cells. Nucl Acids Res (1988) 16:1215. doi:10.1093/nar/16.3.1215

18. Lando, M, Holden, M, Bergersen, LC, Svendsrud, DH, Stokke, T, Sundfør, K, et al. Gene Dosage, Expression, and Ontology Analysis Identifies Driver Genes in the Carcinogenesis and Chemoradioresistance of Cervical Cancer. PLoS Genet (2009) 5:e1000719. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1000719

19. Ottone, F, Miotti, S, Bottini, C, Bagnoli, M, Perego, P, Colnaghi, MI, et al. Relationship between Folate-Binding Protein Expression and Cisplatin Sensitivity in Ovarian Carcinoma Cell Lines. Br J Cancer (1997) 76:77–82. doi:10.1038/bjc.1997.339

20. Bièche, I, Girault, I, Urbain, E, Tozlu, S, and Lidereau, R. Relationship between Intratumoral Expression of Genes Coding for Xenobiotic-Metabolizing Enzymes and Benefit from Adjuvant Tamoxifen in Estrogen Receptor Alpha-Positive Postmenopausal Breast Carcinoma. Breast Cancer Res (2004) 6:R252–63. doi:10.1186/bcr784

21. Chacko, P, Joseph, T, Mathew, BS, Rajan, B, and Pillai, MR. Role of Xenobiotic Metabolizing Gene Polymorphisms in Breast Cancer Susceptibility and Treatment Outcome. Mutat Res (2005) 581:153–63. doi:10.1016/j.mrgentox.2004.11.018

22. Heubner, M, Wimberger, P, Riemann, K, Kasimir-Bauer, S, Otterbach, F, Kimmig, R, et al. The CYP1A1 Ile462Val Polymorphism and Platinum Resistance of Epithelial Ovarian Neoplasms. Oncol Res (2010) 18:343–7. doi:10.3727/096504010x12626118079903

23. Gonzalez, FJ. Role of Cytochromes P450 in Chemical Toxicity and Oxidative Stress: Studies with CYP2E1. Mutat Res (2005) 569:101–10. doi:10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2004.04.021

24. Ginsberg, G, Angle, K, Guyton, K, and Sonawane, B. Polymorphism in the DNA Repair Enzyme XRCC1: Utility of Current Database and Implications for Human Health Risk Assessment. Mutat Res (2011) 727:1–15. doi:10.1016/j.mrrev.2011.02.001

25. Sterpone, S, and Cozzi, R. Influence of XRCC1 Genetic Polymorphisms on Ionizing Radiation-Induced DNA Damage and Repair. J Nucleic Acids (2010) 2010:780369. doi:10.4061/2010/780369

26. Hoeijmakers, JH. Genome Maintenance Mechanisms for Preventing Cancer. Nature (2001) 411:366–74. doi:10.1038/35077232

27. Hasselbach, L, Haase, S, Fischer, D, Kolberg, HC, and Stürzbecher, HW. Characterisation of the Promoter Region of the Human DNA-Repair Gene Rad51. Eur J Gynaecol Oncol (2005) 26:589–98.

28. Cheng, XD, Lu, WG, Ye, F, Wan, XY, and Xie, X. The Association of XRCC1 Gene Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms with Response to Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy in Locally Advanced Cervical Carcinoma. J Exp Clinl Cancer Res (2009) 28:91. doi:10.1186/1756-9966-28-91

29. Khrunin, AV, Moisseev, A, Gorbunova, V, and Limborska, S. Genetic Polymorphisms and the Efficacy and Toxicity of Cisplatin-Based Chemotherapy in Ovarian Cancer Patients. Pharmacogenomics J (2010) 10:54–61. doi:10.1038/tpj.2009.45

30. Kim, HS, Kim, MK, Chung, HH, Kim, JW, Park, NH, Song, YS, et al. Genetic Polymorphisms Affecting Clinical Outcomes in Epithelial Ovarian Cancer Patients Treated with Taxanes and Platinum Compounds: A Korean Population-Based Study. Gynecol Oncol (2009) 113:264–9. doi:10.1016/j.ygyno.2009.01.002

31. Miao, J, Zhang, X, and Tang, QL. Prediction Value of XRCC 1 Gene Polymorphism on the Survival of Ovarian Cancer Treated by Adjuvant Chemotherapy. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev (2012) 13:5007–10. doi:10.7314/apjcp.2012.13.10.5007

32. Monteiro, E, Varzim, G, Pires, AM, Teixeira, M, and Lopes, C. Cyclin D1 A870G Polymorphism and Amplification in Laryngeal Squamous Cell Carcinoma: Implications of Tumor Localization and Tobacco Exposure. Cancer Detect Prev (2004) 28:237–43. doi:10.1016/j.cdp.2004.04.005

33. Griffin, CS, Simpson, PJ, Wilson, CR, and Thacker, J. Mammalian Recombination-Repair Genes XRCC2 and XRCC3 Promote Correct Chromosome Segregation. Nat Cell Biol (2000) 2:757–61. doi:10.1038/35036399

34. Yin, M, Liao, Z, Huang, YJ, Liu, Z, Yuan, X, Gomez, D, et al. Polymorphisms of Homologous Recombination Genes and Clinical Outcomes of Non-small Cell Lung Cancer Patients Treated with Definitive Radiotherapy. PloS one (2011) 6:e20055. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0020055

35. Li, D, Liu, H, Jiao, L, Chang, DZ, Beinart, G, Wolff, RA, et al. Significant Effect of Homologous Recombination DNA Repair Gene Polymorphisms on Pancreatic Cancer Survival. Cancer Res (2006) 66:3323–30. doi:10.1158/0008-5472.can-05-3032

36. Cheng, J, Liu, W, Zeng, X, Zhang, B, Guo, Y, Qiu, M, et al. XRCC3 Is a Promising Target to Improve the Radiotherapy Effect of Esophageal Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Cancer Sci (2015) 106:1678–86. doi:10.1111/cas.12820

Keywords: cervical cancer, CYP1A1, CYP2E1, DNA repair gene, polymorphisms, treatment outcome

Citation: Abbas M, Kushwaha VS, Srivastava K and Banerjee M (2022) Understanding Role of DNA Repair and Cytochrome p-450 Gene Polymorphisms in Cervical Cancer Patient Treated With Concomitant Chemoradiation. Br J Biomed Sci 79:10120. doi: 10.3389/bjbs.2021.10120

Received: 18 October 2021; Accepted: 23 December 2021;

Published: 24 February 2022.

Copyright © 2022 Abbas, Kushwaha, Srivastava and Banerjee. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Monisha Banerjee, bW9uaXNoYWJhbmVyamVlMzBAZ21haWwuY29t, bWhnbHVja25vd0B5YWhvby5jb20=

Mohammad Abbas1,2

Mohammad Abbas1,2 Monisha Banerjee

Monisha Banerjee