Introduction

Do we all experience a phase of dystonia in our lives? Surprisingly, yes. Based on the current classification, dystonia is defined as “a movement disorder characterized by sustained or intermittent muscle contractions causing abnormal, often repetitive, movements, postures, or both” [1, 2]. Based on this definition, it appears that we all pass through a physiological dystonia phase, at least early in life [3]. Indeed, movements typically considered dystonic (abnormal) in pediatric and adult stages [1, 4] are not phenotypically dissimilar from those observed in healthy neonates and infants [5, 6]. For example, newborns and infants display involuntary paroxysmal behaviors - movements that are non-epileptic and arise from normal developmental trajectories and exploratory motor skills (e.g., arm rotations, oral-buccal-lingual movements, biking, and pacing) [7–10]. Standard electroencephalographic (EEG) or video-EEG recordings performed during these neonatal movements generally do not indicate seizure activity or other encephalopathic conditions [11–13].

Interestingly, even before birth, fetuses display dystonia-like stereotyped movements [14]. These movements occur in a unique environment, with the fetus fully immersed in a microgravity-like amniotic fluid environment [15]. Throughout gestation, fetal movements interact with increasing gravitational forces, a result of fetal growth and the gradual reduction of amniotic fluid volume [16–18]. Remarkably, these motor, neuromuscular, and brain developmental processes are finely regulated by specific genetic, molecular, and physiological mechanisms, many of which have only recently begun to be understood in terms of timing and their developmental (ontogenic) and evolutionary (phylogenic) roles [19–22].

At another end of life experiences, humans (and some animals) may spend time in space, either for occupational or recreational purposes [23]. In these conditions - ranging from hours to months - subjects encounter changes and adaptations in motor and non-motor functions due to weightlessness, or microgravity, which is a state of near or complete absence of the sensation of weight. Life on Earth, and animal life in general, has evolved to adapt motor and non-motor behaviors in response to gravity [24, 25]. Through various sensory and motor adaptations, humans and land animals maintain postural equilibrium, coordinating agonist-antagonist muscle processing to survive [26]. This coordination involves complex integration of visual, vestibular, and somatosensory inputs to counteract gravity’s effects [27].

Cerebellum and gravity adaptation

Neuroanatomically, the cerebellum (CRB) is a central hub for gravity response and adaptation, primarily due to its direct connections with both ocular- and gravity-sensing vestibular receptors [28]. The CRB is integral to spatial orientation and gait regulation via the spino-cerebellum and ponto-cerebellum systems, which are essential for motor control, coordination, and learning, making it the main center for anti-gravity processes [29–32]. Both on Earth and in space, dystonic movements disrupt gravity perception, affecting posture, gait, and fine motor coordination [33]. In space, where gravitational forces are reduced, the vestibulocerebellar system rapidly adapts, recalibrating its responses to accommodate the altered gravitational environment [34]. This adaptation occurs almost instantly, similar to the adjustment newborns make at birth when transitioning from microgravity in the womb to Earth’s full gravity [19, 35].

Understanding cerebellar responses to altered gravity in both space and prenatal environments could deepen insights into gravity-related consequences for astronauts, fetuses, infants, and patients with dystonia [36]. Gravity shifts, such as weightlessness, trigger neuromuscular, sensory, and vestibular changes that may contribute to distinct syndromic features, particularly in astronauts [37, 38]. Among these phenomena, dystonia-like movements stand out [39–41]. Notably, though similar dystonia-like movements appear in healthy individuals on Earth (pre- and post-birth), in microgravity, and in patients with dystonia, the underlying causes may differ. However, phenotypic, pathogenetic and adaptive similarities and differences across different dystonia-appearing phenomena could still provide meaningful and possibly unexpected tools for the treatment of dystonia in general or specific forms of it [42]. For example, it is expected that hypergravity environments exacerbate symptoms or lead to different manifestations of muscle control challenges. Increased gravitational forces may amplify muscle rigidity or spasms in those with dystonia. On the other hand, for individuals with dystonia, exposure to microgravity (like fetuses) could have therapeutic effects. More specifically, microgravity environments tend to decrease overall muscle tone and reduce physical resistance and consequently, people with dystonia could ease some symptoms related to muscle contractions and spasms. Moreover, microgravity may offer temporary relief from the continuous muscle firing and rigidity that characterizes dystonia. In addition, microgravity could set changes in neurocircuits feedback loops, and specifically in the BG-CRB inputs since it alters proprioception and how the brain interprets muscle feedback and so potentially modifying movement patterns. We hypothesize that the same adaptive phenomena are actually present in the opposite direction at the passage from in-utero (microgravity) to extra-utero (at birth). A better understanding of the genetic or metabolic causes and processes of these BG-CRB mechanisms at birth could actually provide new rehabilitative approaches for dystonia patients in general or for those type of dystonia (isolated dystonia) that appear physiopathological closer to the neonatal events. Importantly, this hypothesis, while still speculative, seems to be supported by studies using animals in a microgravitational environment during and after pregnancy [43, 44]. Furthermore, microgravity leads to muscle atrophy over time, and without gravity as resistance, muscles lose strength. For someone with dystonia, muscle weakening might temporarily lessen spastic contractions but could also lead to long-term challenges in muscle control. In general, microgravity effects exploration has expanded our understanding of neurological conditions by showing how the absence of gravity affects motor control and muscle function [45, 46]. This knowledge might inform treatments that mimic the effects of microgravity to help manage dystonia symptoms on Earth, such as specialized anti-gravity rehabilitation apparatuses.

In general, we propose that motor phenomena in space and the womb may be more accurately linked to cerebellar mechanisms rather than primarily to basal ganglia (BG) dysfunction, as seen in many dystonia cases [47, 48]. In particular, cerebellar injury in utero have been recently the focus of various studies that have applied non-invasive imaging techniques (i.e., MRI, ultrasound) to analyze in more detail, especially in neuroanatomical terms, cerebellar lesions in utero and their clinical consequences during gestation and after birth [49]. Cerebellar injury in utero are associated to both motor and non-motor consequences and among the motor abnormalities alterations of fine motor skills have been described and some of them have dystonia-like features. Moreover, the biological and neurophysiological aspects of the synchronization between vestibular system development and microgravity-to-gravity passage started to offer more specific notions about the possibility of cerebellar injury and their consequence on the motor and vestibular system [50]. Furthermore, study of hypergravity (in animals) have shown that hypergravity exposure during different period of gestation deeply alter cerebellar development and Purkinje cells in particular [51, 52]. Purkinje cells have been shown to be affected by subtle changes in dystonia human cases [48, 53] and specific genes have been involved in paroxysmal dystonia episodes in mice [54]. Moreover, a study by Dooley JC [55] described, in an animal model, how the brain develops internal models for tracking limb movements in real-time, even without visual cues, to avoid delays from sensory feedback. These investigators found that, in rats, these cerebellum-dependent internal models begin forming by postnatal day 20 (P20), allowing the brain to predict and mirror movements rather than reacting to them after the fact. In particular, observing neural activity during spontaneous limb twitches in sleep, the study showed that only by P20 did a specific part of the thalamus (the ventral lateral nucleus, receiving cerebellar input) synchronize precisely with limb movement. These findings suggest that sleep twitches help develop and refine these internal movement models. These findings, if confirmed in newborns or in-utero babies, would support our hypothesis for which cerebellar-dependent internal movement modules could be associated to normal dystonic-like movement during normal development or if affected by different types of injury could be actually related to prolonged dystonic-like movements early in life and later.

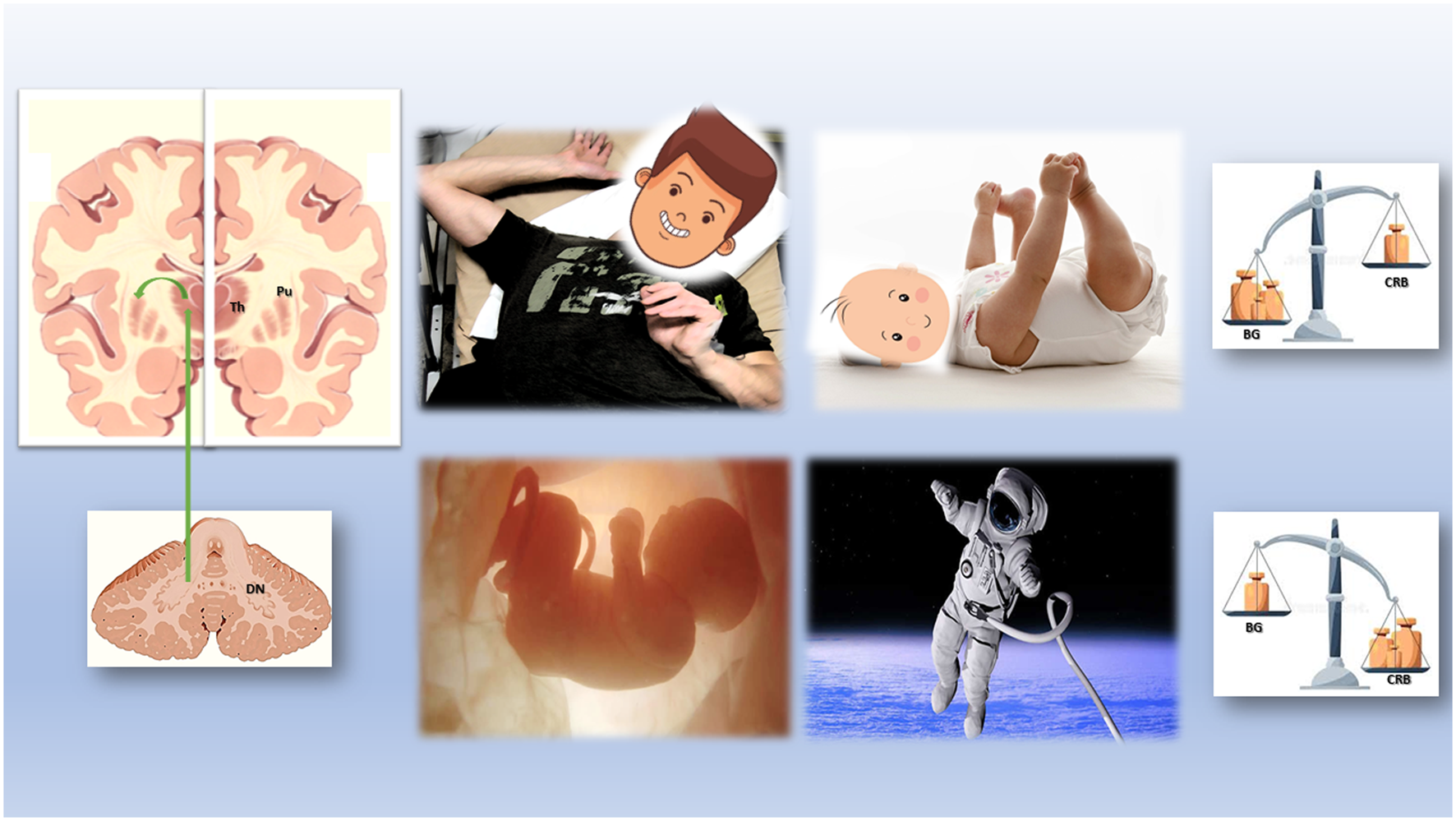

The overlapping yet distinct causes of these motor phenomena, despite genetic or environmental differences, could illuminate previously unexplored brain mechanisms involved in dystonia and dystonia-like movements across various life stages. A valuable approach would be to examine these movements for neuroanatomical, neurophysiological, and neurotransmitter-based similarities and differences, from fetal life to life in space (see Figure 1). To test this hypothesis one of the possible analysis would be to systematically record (video-ultrasound) and score in-utero vs. extra-utero “dystonia-like” movements as related to specific cerebellar injury (vascular, developmental, metabolic). In addition, this set of data should be related to the specific timing and development of the vestibular system. These types of correlations if confirmed to be associated to an increase incidence of dystonia-like phenomena during the first month of life and later, could be an excellent clinicometrics tool to assess and mitigate the long-term effect of the cerebellar-vestibular dysfunction manifesting as a dystonic disorder. Moreover, a similar approach could be used to study the long-term effects of microgravity in astronauts exposed for a long period of time to a weightlessness environment and mitigate the serious effects described after a “quick” hypergravity change when back on Earth [56–58].

FIGURE 1

Physiological and Pathologic Cerebellum-Basal Ganglia Interactions from the womb to the space.

Clinically, the CRB’s role in dystonia has often been overlooked in favor of BG involvement. However, recent debates have increasingly recognized the CRB’s influence, challenging the idea that dystonia is solely a BG-driven condition [59–61]. Evidence now suggests that both BG and CRB, along with their associated neurocircuits and neurotransmitters, are central to dystonia’s pathogenesis [53]. Rather than one region exclusively dominating, the involvement of BG vs. CRB appears to vary dynamically. Depending on the dystonic disorder’s type, timing, and the specific genetic, developmental, and environmental conditions present, either BG or CRB dysfunction may predominate, a phenomenon that could be termed “dynamic BG-CRB shifting.”

Direct synaptic connections between cerebellum and basal ganglia: a game-changer

One of the most transformative breakthroughs in the cerebellum (CRB) and basal ganglia (BG) debate has been the recent discovery of direct disynaptic connections between the CRB and BG in non-human primates - a finding that is likely applicable to humans as well [62]. For decades, it was widely believed that the CRB and BG operated in isolation, with no direct connectivity. This assumption led researchers to attribute many “cerebellar” phenomena, such as the resting tremor seen in Parkinson’s disease (PD), exclusively to BG dysfunction. The recent neuroanatomical discovery of these connections has prompted a reevaluation of the pathophysiological mechanisms underlying various movement disorders, including PD and dystonia.

The disynaptic connection between the CRB and BG - mediated through the thalamus - holds significant physiological and pathophysiological implications. Through this pathway, the CRB sends signals to the BG, which influence both motor planning and execution. This connection may help to synchronize the CRB’s role in movement coordination with the BG’s role in movement initiation and control. Furthermore, the CRB influences the subthalamic nucleus, a central structure within the BG. This connection enables the CRB to indirectly modulate BG circuits involved in movement control, including those that are altered in dystonia.

Adding to this complexity, the CRB appears to have a notable role in dopaminergic modulation, which is increasingly recognized as a key factor in movement disorders. Research suggests that the dopaminergic system within the cerebellum may also regulate vestibular circuits, adding another layer of influence on balance and motor stability [63]. Although further research is needed to determine how these dopaminergic pathways specifically relate to dystonic symptoms, this new understanding of the CRB’s neuroanatomy and neurochemical connections is already reshaping our understanding of motor abnormalities. These findings underscore the need for a paradigm shift in the study and treatment of primary dystonia. No longer can we view dystonia solely through a BG-centered lens; rather, we must adopt a dynamic BG-CRB model that recognizes the interplay between these two regions [64]. This broader perspective opens new avenues for understanding and addressing dystonia’s complex symptomatology.

Does white matter matter?

Recent advancements in neuroimaging have spurred interest in white matter (WM) alterations as a critical factor in dystonia research. Subtle but pathophysiologically significant WM changes have been documented across various forms of dystonia, underscoring the potential role of WM integrity in motor dysfunction [65–69]. Intriguingly, MRI scans of astronauts returning from extended space missions also reveal unique WM changes, likely due to the effects of prolonged weightlessness on motor control [39, 58, 70]. These findings highlight the adaptability of the cerebellum-basal ganglia (CRB-BG) circuit and suggest that neuroplasticity - especially involving WM changes - may play a significant role in dystonia’s development and manifestations. Indeed, WM changes have been observed in dystonia patients and even in response to targeted peripheral treatments, such as botulinum toxin injections for cervical dystonia [71].

Emerging research increasingly implicates cerebellar WM in dystonia, suggesting a larger-than-expected role for the cerebellum in this disorder. WM in the cerebellum comprises myelinated axons that connect it to the basal ganglia, motor cortex, and brainstem, facilitating complex motor coordination and communication. Alterations within these WM pathways - whether structural or metabolic - could be critical to the abnormal muscle contractions and motor control issues typical of dystonia. Diffusion tensor imaging (DTI), which assesses WM microstructure, has identified altered WM integrity in dystonia patients, particularly affecting pathways like the cerebello-thalamo-cortical circuit, which links the cerebellum to the thalamus and cortex. Disruptions in this pathway impair the cerebellum’s ability to relay precise timing and coordination signals, contributing to the disordered motor output characteristic of dystonia.

Further, WM disruptions within the CRB-BG circuit affect connectivity between the cerebellum and basal ganglia, skewing the balance between motor initiation (a BG function) and motor coordination (a CRB function). This imbalance may contribute to dystonia’s hallmark symptoms: disorganized movement timing, abnormal muscle contractions, and postural irregularities. Additionally, the cerebellum’s involvement extends beyond mere coordination to encompass sensorimotor integration, which is essential for refining movement through sensory feedback. WM alterations interfere with this sensory processing, leading to proprioceptive challenges and decreased movement accuracy - effects that closely resemble those reported by astronauts and likely mirror the sensory experiences of neonates during the first days of life outside the womb. In fact, imaging studies in neonates, including preterm infants, reveal that WM integrity is closely linked to motor development and could predict dystonia-like motor abnormalities [72, 73].

These findings underscore the importance of WM integrity within the BG-CRB framework, validating WM as a key factor in both typical and pathological motor processes. By focusing on WM changes within this framework, we may open new avenues for personalized treatments in dystonia and improve our understanding of motor adaptation under unique physiological conditions.

Discussion and future perspectives

This opinion article explores dystonia and dystonia-like disorders through the lens of recent pathophysiological findings in both dystonia patients and individuals in unique environments - such as the womb and space. We advocate for a new Cerebellum-Basal Ganglia (CRB-BG) paradigm to advance our understanding of dystonic phenomena. This approach is poised to benefit from emerging technologies and methodologies, including advanced neuroimaging, omics, telemedicine, neuroanatomy, and neuropathology, in both human and animal models.

We propose examining this CRB-BG paradigm across three distinct environments: the womb, Earth, and space. This “environmental triad” offers a comprehensive framework for studying dystonic phenomena within physiological states (e.g., the floating fetus), pathological states (e.g., generalized dystonia), and paraphysiological states (e.g., human beings in microgravity). By exploring these varied environments, we aim to improve personalized treatment strategies for dystonia patients and address the motor control challenges that long-term space travel may pose.

Statements

Author contributions

DI contributed to the ideation, writing and content of this manuscript.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This study was supported by MEDAL (MovemEnt Disorders Across Lifespan) program, Biomedical Research Institute of New Jersey (BRInj), Funding period 2023-24.

Acknowledgments

To all dystonia patients, moms and babies, astronauts and space travelers that gave their consent, time and energy to collaborate for a better understanding of dystonic and developmental movements.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

References

1.

Albanese A Bhatia K Bressman SB Delong MR Fahn S Fung VS et al Phenomenology and classification of dystonia: a consensus update. Mov Disord (2013) 28(7):863–73. 10.1002/mds.25475

2.

Jinnah HA Factor SA . Diagnosis and treatment of dystonia. Neurol Clin (2015) 33(1):77–100. 10.1016/j.ncl.2014.09.002

3.

Kuiper MJ Brandsma R Lunsing RJ Eggink H Ter Horst HJ Bos AF et al The neurological phenotype of developmental motor patterns during early childhood. Brain Behav (2019) 9(1):e01153. 10.1002/brb3.1153

4.

Fernández-Alvarez E Nardocci N . Update on pediatric dystonias: etiology, epidemiology, and management. Degener Neurol Neuromuscul Dis (2012) 2:29–41. 10.2147/DNND.S16082

5.

Brandsma R Spits AH Kuiper MJ Lunsing RJ Burger H Kremer HP et al Ataxia rating scales are age-dependent in healthy children. Dev Med Child Neurol (2014) 56(6):556–63. 10.1111/dmcn.12369

6.

Kuiper MJ Vrijenhoek L Brandsma R Lunsing RJ Burger H Eggink H et al The burke-fahn-marsden dystonia rating scale is age-dependent in healthy children. Mov Disord Clin Pract (2016) 3(6):580–6. 10.1002/mdc3.12339

7.

Weggemann T Brown JK Fulford GE Minns RA . A study of normal baby movements. Child Care Health Dev (1987) 13(1):41–58. 10.1111/j.1365-2214.1987.tb00522.x

8.

van der Meer AL van der Weel FR Lee DN . The functional significance of arm movements in neonates. Science (1995) 267(5198):693–5. 10.1126/science.7839147

9.

Einspieler C Yang H Bartl-Pokorny KD Chi X Zang FF Marschik PB et al Are sporadic fidgety movements as clinically relevant as is their absence? Early Hum Dev (2015) 91(4):247–52. 10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2015.02.003

10.

Fujihira R Taga G . Dynamical systems model of development of the action differentiation in early infancy: a requisite of physical agency. Biol Cybern (2023) 117(1-2):81–93. 10.1007/s00422-023-00955-y

11.

Huntsman RJ Lowry NJ Sankaran K . Nonepileptic motor phenomena in the neonate. Paediatr Child Health (2008) 13(8):680–4. 10.1093/pch/13.8.680

12.

Devinsky O Gazzola D LaFrance WC Jr . Differentiating between nonepileptic and epileptic seizures. Nat Rev Neurol (2011) 7(4):210–20. 10.1038/nrneurol.2011.24

13.

Jung SY Kang JW . Is it really a seizure? The challenge of paroxysmal nonepileptic events in young infants. Clin Exp Pediatr (2021) 64(8):384–92. 10.3345/cep.2020.00451

14.

Huecker BR Jamil RT Thistle J . Fetal movement. 2023 feb 5. In: StatPearls treasure island (FL). StatPearls Publishing (2024).

15.

Bradford BF Cronin RS McKinlay CJD Thompson JMD Mitchell EA Stone PR et al A diurnal fetal movement pattern: findings from a cross-sectional study of maternally perceived fetal movements in the third trimester of pregnancy. PLoS One (2019) 14(6):e0217583. 10.1371/journal.pone.0217583

16.

Sparling JW Van Tol J Chescheir NC . Fetal and neonatal hand movement. Phys Ther (1999) 79(1):24–39. 10.1093/ptj/79.1.24

17.

Almli CR Ball RH Wheeler ME . Human fetal and neonatal movement patterns: gender differences and fetal-to-neonatal continuity. Dev Psychobiol (2001) 38(4):252–73. 10.1002/dev.1019

18.

de Vries JI Fong BF . Normal fetal motility: an overview. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol (2006) 27(6):701–11. 10.1002/uog.2740

19.

Nguon K Ladd B Sajdel-Sulkowska EM . Exposure to altered gravity during specific developmental periods differentially affects growth, development, the cerebellum and motor functions in male and female rats. Adv Space Res (2006) 38(6):1138–47. 10.1016/j.asr.2006.09.007

20.

Richter A Hamann M Wissel J Volk HA . Dystonia and paroxysmal dyskinesias: under-recognized movement disorders in domestic animals? A comparison with human dystonia/paroxysmal dyskinesias. Front Vet Sci (2015) 2:65. 10.3389/fvets.2015.00065

21.

Hayat TTA Rutherford MA . Neuroimaging perspectives on fetal motor behavior. Neurosci Biobehav Rev (2018) 92:390–401. 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2018.06.001

22.

Santifort KM Mandigers PJJ . Dystonia in veterinary neurology. J Vet Intern Med (2022) 36(6):1872–81. 10.1111/jvim.16532

23.

Krittanawong C Singh NK Scheuring RA Urquieta E Bershad EM Macaulay TR et al Human health during space travel: state-of-the-art review. Cells (2022) 12(1):40. 10.3390/cells12010040

24.

Gaveau J Grospretre S Berret B Angelaki DE Papaxanthis C . A cross-species neural integration of gravity for motor optimization. Sci Adv (2021) 7(15):eabf7800. 10.1126/sciadv.abf7800

25.

Badalì C Wollseiffen P Schneider S . Shades of gravity - effects of planetary gravity levels on electrocortical activity and neurocognitive performance. Brain Struct Funct (2024) 229(5):1265–77. 10.1007/s00429-024-02803-6

26.

Cialdai F Brown AM Baumann CW Angeloni D Baatout S Benchoua A et al How do gravity alterations affect animal and human systems at a cellular/tissue level? NPJ Microgravity (2023) 9(1):84. 10.1038/s41526-023-00330-y

27.

Willis CRG Calvaruso M Angeloni D Baatout S Benchoua A Bereiter-Hahn J et al How to obtain an integrated picture of the molecular networks involved in adaptation to microgravity in different biological systems? NPJ Microgravity (2024) 10(1):50. 10.1038/s41526-024-00395-3

28.

MacNeilage PR Glasauer S . Gravity perception: the role of the cerebellum. Curr Biol (2018) 28(22):R1296-R1298–R1298. 10.1016/j.cub.2018.09.053

29.

Gouhier A Villette V Mathieu B Ayon A Bradley J Dieudonné S . Identification and organization of a postural anti-gravity module in the cerebellar vermis. Neuroscience (2024)(24) S0306–4522. 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2024.06.006

30.

Platho-Elwischger K Kranz G Sycha T Dunkler D Rommer P Mueller C et al Plasticity of static graviceptive function in patients with cervical dystonia. J Neurol Sci (2017) 373:230–5. 10.1016/j.jns.2017.01.007

31.

Doroshin A Jillings S Jeurissen B Tomilovskaya E Pechenkova E Nosikova I et al Brain connectometry changes in space travelers after long-duration spaceflight. Front Neural Circuits (2022) 16:815838. 10.3389/fncir.2022.815838

32.

Carriot J Mackrous I Cullen KE . Challenges to the vestibular system in space: how the brain responds and adapts to microgravity. Front Neural Circuits (2021) 15:760313. 10.3389/fncir.2021.760313

33.

Clément G Kuldavletova O Macaulay TR Wood SJ Navarro Morales DC Toupet M et al Cognitive and balance functions of astronauts after spaceflight are comparable to those of individuals with bilateral vestibulopathy. Front Neurol (2023) 14:1284029. 10.3389/fneur.2023.1284029

34.

Newman DJ Jackson DK Bloomberg JJ . Altered astronaut lower limb and mass center kinematics in downward jumping following space flight. Exp Brain Res (1997) 117(1):30–42. 10.1007/pl00005788

35.

Theotokis P Manthou ME Deftereou TE Miliaras D Meditskou S . Addressing spaceflight biology through the lens of a histologist-embryologist. Life (Basel) (2023) 13(2):588. 10.3390/life13020588

36.

Barbosa P Warner TT . Dystonia. Handb Clin Neurol (2018) 159:229–36. 10.1016/B978-0-444-63916-5.00014-8

37.

Reschke MF Bloomberg JJ Harm DL Paloski WH Layne C McDonald V . Posture, locomotion, spatial orientation, and motion sickness as a function of space flight. Brain Res Brain Res Rev (1998) 28(1-2):102–17. 10.1016/s0165-0173(98)00031-9

38.

Holden K Greene M Vincent E Sándor A Thompson S Feiveson A et al Effects of long-duration microgravity and gravitational transitions on fine motor skills. Hum Factors (2023) 65(6):1046–58. 10.1177/00187208221084486

39.

Roy-O'Reilly M Mulavara A Williams T . A review of alterations to the brain during spaceflight and the potential relevance to crew in long-duration space exploration. NPJ Microgravity (2021) 7(1):5. 10.1038/s41526-021-00133-z

40.

Rezaei S Seyedmirzaei H Gharepapagh E Mohagheghfard F Hasankhani Z Karbasi M et al Effect of spaceflight experience on human brain structure, microstructure, and function: systematic review of neuroimaging studies. Brain Imaging Behav (2024) 18:1256–79. 10.1007/s11682-024-00894-7

41.

Brüggemann N . Contemporary functional neuroanatomy and pathophysiology of dystonia. J Neural Transm (Vienna) (2021) 128(4):499–508. 10.1007/s00702-021-02299-y

42.

Bradnam LV Meiring RM Boyce M McCambridge A . Neurorehabilitation in dystonia: a holistic perspective. J Neural Transm (Vienna) (2021) 128(4):549–58. 10.1007/s00702-020-02265-0

43.

Ronca AE Alberts JR . Physiology of a microgravity environment selected contribution: effects of spaceflight during pregnancy on labor and birth at 1 G. J Appl Physiol (1985)2000) 89(2):849–54. 10.1152/jappl.2000.89.2.849

44.

Wakayama S Kikuchi Y Soejima M Hayashi E Ushigome N Yamazaki C et al Effect of microgravity on mammalian embryo development evaluated at the International Space Station. iScience (2023) 26(11):108177. 10.1016/j.isci.2023.108177

45.

McGregor HR Hupfeld KE Pasternak O Beltran NE De Dios YE Bloomberg JJ et al Impacts of spaceflight experience on human brain structure. Sci Rep (2023) 13(1):7878. 10.1038/s41598-023-33331-8

46.

Davis T Tabury K Zhu S Angeloni D Baatout S Benchoua A et al How are cell and tissue structure and function influenced by gravity and what are the gravity perception mechanisms? NPJ Microgravity (2024) 10(1):16. 10.1038/s41526-024-00357-9

47.

Sumarac S Spencer KA Steiner LA Fearon C Haniff EA Kühn AA et al Interrogating basal ganglia circuit function in people with Parkinson's disease and dystonia. Elife (2024) 12:RP90454. 10.7554/eLife.90454

48.

Tewari A Fremont R Khodakhah K . It's not just the basal ganglia: cerebellum as a target for dystonia therapeutics. Mov Disord (2017) 32(11):1537–45. 10.1002/mds.27123

49.

Limperopoulos C Chilingaryan G Sullivan N Guizard N Robertson RL du Plessis AJ . Injury to the premature cerebellum: outcome is related to remote cortical development. Cereb Cortex (2014) 24(3):728–36. 10.1093/cercor/bhs354

50.

Jamon M . The development of vestibular system and related functions in mammals: impact of gravity. Front Integr Neurosci (2014) 8:11. 10.3389/fnint.2014.00011

51.

Sajdel-Sulkowska EM Nguon K Sulkowski ZL Rosen GD Baxter MG . Purkinje cell loss accompanies motor impairment in rats developing at altered gravity. Neuroreport (2005) 16(18):2037–40. 10.1097/00001756-200512190-00014

52.

Noh W Lee M Kim HJ Kim KS Yang S . Hypergravity induced disruption of cerebellar motor coordination. Sci Rep (2020) 10(1):4452. 10.1038/s41598-020-61453-w

53.

Morigaki R Miyamoto R Matsuda T Miyake K Yamamoto N Takagi Y . Dystonia and cerebellum: from bench to bedside. Life (Basel) (2021) 11(8):776. 10.3390/life11080776

54.

Kim H Melliti N Breithausen E Michel K Colomer SF Poguzhelskaya E et al Paroxysmal dystonia results from the loss of RIM4 in Purkinje cells. Brain (2024) 147(9):3171–88. 10.1093/brain/awae081

55.

Dooley JC Sokoloff G Blumberg MS . Movements during sleep reveal the developmental emergence of a cerebellar-dependent internal model in motor thalamus. Curr Biol (2021) 31(24):5501–11.e5. 10.1016/j.cub.2021.10.014

56.

Tominari T Ichimaru R Taniguchi K Yumoto A Shirakawa M Matsumoto C et al Hypergravity and microgravity exhibited reversal effects on the bone and muscle mass in mice. Sci Rep (2019) 9(1):6614. 10.1038/s41598-019-42829-z

57.

Mhatre SD Iyer J Puukila S Paul AM Tahimic CGT Rubinstein L et al Neuro-consequences of the spaceflight environment. Neurosci Biobehav Rev (2022) 132:908–35. 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2021.09.055

58.

Jones CW Overbey EG Lacombe J Ecker AJ Meydan C Ryon K et al Molecular and physiological changes in the SpaceX Inspiration4 civilian crew. Nature (2024) 632(8027):1155–64. 10.1038/s41586-024-07648-x

59.

Kaji R Bhatia K Graybiel AM . Pathogenesis of dystonia: is it of cerebellar or basal ganglia origin?J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry (2018) 89(5):488–92. 10.1136/jnnp-2017-316250

60.

Matsuda T Morigaki R Hayasawa H Koyama H Oda T Miyake K et al Striatal parvalbumin interneurons are activated in a mouse model of cerebellar dystonia. Dis Model Mech (2024) 17(5):dmm050338. 10.1242/dmm.050338

61.

Neychev VK Fan X Mitev VI Hess EJ Jinnah HA . The basal ganglia and cerebellum interact in the expression of dystonic movement. Brain (2008) 131(Pt 9):2499–509. 10.1093/brain/awn168

62.

Bostan AC Strick PL . The basal ganglia and the cerebellum: nodes in an integrated network. Nat Rev Neurosci (2018) 19(6):338–50. 10.1038/s41583-018-0002-7

63.

Canton-Josh JE Qin J Salvo J Kozorovitskiy Y . Dopaminergic regulation of vestibulo-cerebellar circuits through unipolar brush cells. Elife (2022) 11:e76912. 10.7554/eLife.76912

64.

Hanssen H Heldmann M Prasuhn J Tronnier V Rasche D Diesta CC et al Basal ganglia and cerebellar pathology in X-linked dystonia-parkinsonism. Brain (2018) 141(10):2995–3008. 10.1093/brain/awy222

65.

Giannì C Piervincenzi C Belvisi D Tommasin S De Bartolo MI Ferrazzano G et al Cortico-subcortical white matter bundle changes in cervical dystonia and blepharospasm. Biomedicines (2023) 11(3):753. 10.3390/biomedicines11030753

66.

Tomić A Sarasso E Basaia S Dragašević-Misković N Svetel M Kostić VS et al Structural brain heterogeneity underlying symptomatic and asymptomatic genetic dystonia: a multimodal MRI study. J Neurol (2024) 271(4):1767–75. 10.1007/s00415-023-12098-y

67.

Rivera D Roa-Sanchez P Bidó P Speckter H Oviedo J Stoeter P . Cerebral and cerebellar white matter tract alterations in patients with Pantothenate Kinase-Associated Neurodegeneration (PKAN). Parkinsonism Relat Disord (2022) 98:1–6. 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2022.03.017

68.

Lee JK Koppelmans V Riascos RF Hasan KM Pasternak O Mulavara AP et al Spaceflight-associated brain white matter microstructural changes and intracranial fluid redistribution. JAMA Neurol (2019) 76(4):412–9. 10.1001/jamaneurol.2018.4882

69.

Alperin N Bagci AM Lee SH . Spaceflight-induced changes in white matter hyperintensity burden in astronauts. Neurology (2017) 89(21):2187–91. 10.1212/WNL.0000000000004475

70.

Blood AJ Tuch DS Makris N Makhlouf ML Sudarsky LR Sharma N . White matter abnormalities in dystonia normalize after botulinum toxin treatment. Neuroreport (2006) 17(12):1251–5. 10.1097/01.wnr.0000230500.03330.01

71.

Kline JE Illapani VSP Li H He L Yuan W Parikh NA . Diffuse white matter abnormality in very preterm infants at term reflects reduced brain network efficiency. Neuroimage Clin (2021) 31:102739. 10.1016/j.nicl.2021.102739

72.

Spittle AJ Brown NC Doyle LW Boyd RN Hunt RW Bear M et al Quality of general movements is related to white matter pathology in very preterm infants. Pediatrics (2008) 121(5):e1184–9. 10.1542/peds.2007-1924

73.

Dewan MV Weber PD Felderhoff-Mueser U Huening BM Dathe AK . A simple MRI score predicts pathological general movements in very preterm infants with brain injury-retrospective cohort study. Children (Basel) (2024) 11(9):1067. 10.3390/children11091067

Summary

Keywords

dystonia, microgravity, womb, space, basal ganglia-cerebellum system

Citation

Iacono D (2024) Womb, gravity, and space: shifting towards the cerebellum-basal ganglia paradigm in dystonia. Dystonia 3:13871. doi: 10.3389/dyst.2024.13871

Received

30 September 2024

Accepted

05 December 2024

Published

20 December 2024

Volume

3 - 2024

Edited by

Roy Sillitoe, Baylor College of Medicine, United States

Updates

Copyright

© 2024 Iacono.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Diego Iacono, diego.iacono@atlantichealth.org, iacono@brinj.org

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.